Assess time trends in mortality from multiple sclerosis (MS) in the Spanish population (1981–2020), considering the influence of independent effects of gender, age, period, and birth cohort.

MethodsMS deaths and populations needed for calculations were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics. Age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR) and trend analysis were performed using joinpoint regression software. Age-period-cohort (APC) analysis was performed using the web-based statistical tool of the US National Cancer Institute to explore the underlying reason for the MS mortality.

ResultsASMR increased significantly in both women and men (1.7% and 1.2% respectively). The joinpoint analysis detected no trend change for women, but for men it detects a first period where rates remain stable (1981–2000; annual percentage change: −0.7%, not significant) followed by a period of significant increase (2000–2020; 2.6%, P<0.05). For period effects, a steady increase was observed among women since the early 1990s and among men since the late 1990s. A birth cohort-related increase in mortality was detected: women born from 1916 onwards see their risk of MS mortality increase until it peaks in 1956, after which it decreases. A similar pattern is observed in men, albeit with a decade delay (from 1926 to 1966).

ConclusionASMR shows a steady increase in both sexes over the last decades, although it has been more intense in men. The decreasing birth cohort pattern for MS mortality in men born since the mid-1960s and women born since the mid-1950s is similar to APC analyses in other countries.

Evaluar las tendencias temporales de la mortalidad por esclerosis múltiple (EM) en la población española (1981–2020), considerando la influencia de los efectos independientes de sexo, edad, periodo y cohorte de nacimiento.

MétodosLas defunciones por EM y las poblaciones necesarias para los cálculos se obtuvieron del Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Las tasas de mortalidad estandarizadas por edad (ASMR) y el análisis de tendencias se realizaron mediante el programa informático de regresión joinpoint. Se realizó un análisis edad-periodo-cohorte (APC) utilizando la herramienta estadística disponible en la web del Instituto Nacional del Cáncer de EE.UU. para explorar la razón subyacente de la mortalidad por EM.

ResultadosLa ASMR aumentó significativamente tanto en mujeres como en hombres (1,7% y 1,2% respectivamente). El análisis joinpoint no detectó ningún cambio de tendencia para las mujeres, pero para los hombres detecta un primer periodo en el que las tasas permanecen estables (1981–2000; cambio porcentual anual: −0,7%, no significativo) seguido de un periodo de aumento significativo (2000–2020; 2,6%, p<0,05). En cuanto a los efectos de periodo, se observó un aumento constante entre las mujeres desde principios de la década de 1990 y entre los hombres desde finales de esa misma década. Se detectó un aumento de la mortalidad relacionado con la cohorte de nacimiento: las mujeres nacidas a partir de 1916 ven aumentar su riesgo de mortalidad por EM hasta alcanzar un máximo en 1956, tras lo cual disminuye. En los hombres se observa un patrón similar, aunque con una década de retraso (de 1926 a 1966).

ConclusionesLa ASMR muestra un aumento constante en ambos sexos en las últimas décadas, aunque ha sido más intenso en los hombres. El patrón decreciente de la cohorte de nacimiento para la mortalidad por EM en hombres nacidos desde mediados de los 1960s y mujeres nacidas desde mediados de los 1950s es similar a los análisis de APC en otros países.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, and neurodegenerative disease that in 2020 affected approximately 55 000 people in Spain, 500 000 in Europe, and 2.8 million people worldwide.1 It is the leading cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults in developed countries.2

An increase has been observed in the prevalence of MS in several countries,3,4 including Spain,5 which has been attributed to improvements in the design of epidemiological studies, diagnosis, and management of complications, which has improved survival, as well as the overall growth of the population.6 Incidence has also increased, but this change has been attributed to more exhaustive identification of new cases in recent years.7,8

Differences between birth cohorts in disease rates are the main endpoint in age-period-cohort (APC) analyses, which have been long used in cancer9,10 and suicide research11; this approach has also been used in MS, both in Spain12 and in other countries,13,14 as the different hypotheses on its aetiopathogenesis have focused on risk factors acting in early stages of life.

APC analysis separates the different components of time trends, quantifying the events associated with age, period of death, and birth cohort. These factors usually involve different effects on the underlying biological mechanisms and triggering mechanisms of diseases of uncertain cause, such as MS. Thus, age-specific effects suggest that exposures and/or events associated with age that influence the risk of MS, and the effects of the period of death, present different patterns of detection of MS cases, due to changes in the way in which cases are identified (improved diagnosis, classification changes, etc), whereas effects associated with birth cohorts may suggest that risk factor patterns differ from one birth cohort to another.15 In this context, we aim to update the information on MS mortality in Spain and to analyse changes in temporal trends during the period 1981-2020, using an APC analysis.

MethodsData sourcesData on mortality due to MS during the study period (1981–2020) and the corresponding population data were provided by the Spanish National Statistics Institute. We gathered cases classified with code 340 of the 9th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) and code G35 of the ICD-10.

Statistical analysisWe used the Joinpoint Regression software (developed by the US National Cancer Institute for the analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, available at https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/) to calculate age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR) using the direct method (European Standard Population) and analyse time trends.

To apply the APC model, we organised the dataset into 8 5-year periods, from 1981-1985 to 2016-2020, and 11 5-year age groups, from 30-34 to 80-84 years. This resulted in 18 birth cohorts (labelled according to the central year of birth, from 1901 to 1986). We calculated ASMRs for each age group and 5-year period.

To analyse the effects of the period of death, we used an online APC model tool (Biostatistics Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, available at https://analysistools.nci.nih.gov/apc/).

In our findings, we mainly focused on the estimated functions16: cross-sectional age-specific rates, period and cohort rate ratios (RR), as well as local drifts (annual percentage change for each age group) with net drifts (overall annual percentage change). The central age group, central calendar period, and central birth cohort were considered the reference groups in all APC analyses. We used Wald chi-square tests to determine significance of estimable functions. The significance threshold was set P<.05 in all two-tailed tests.

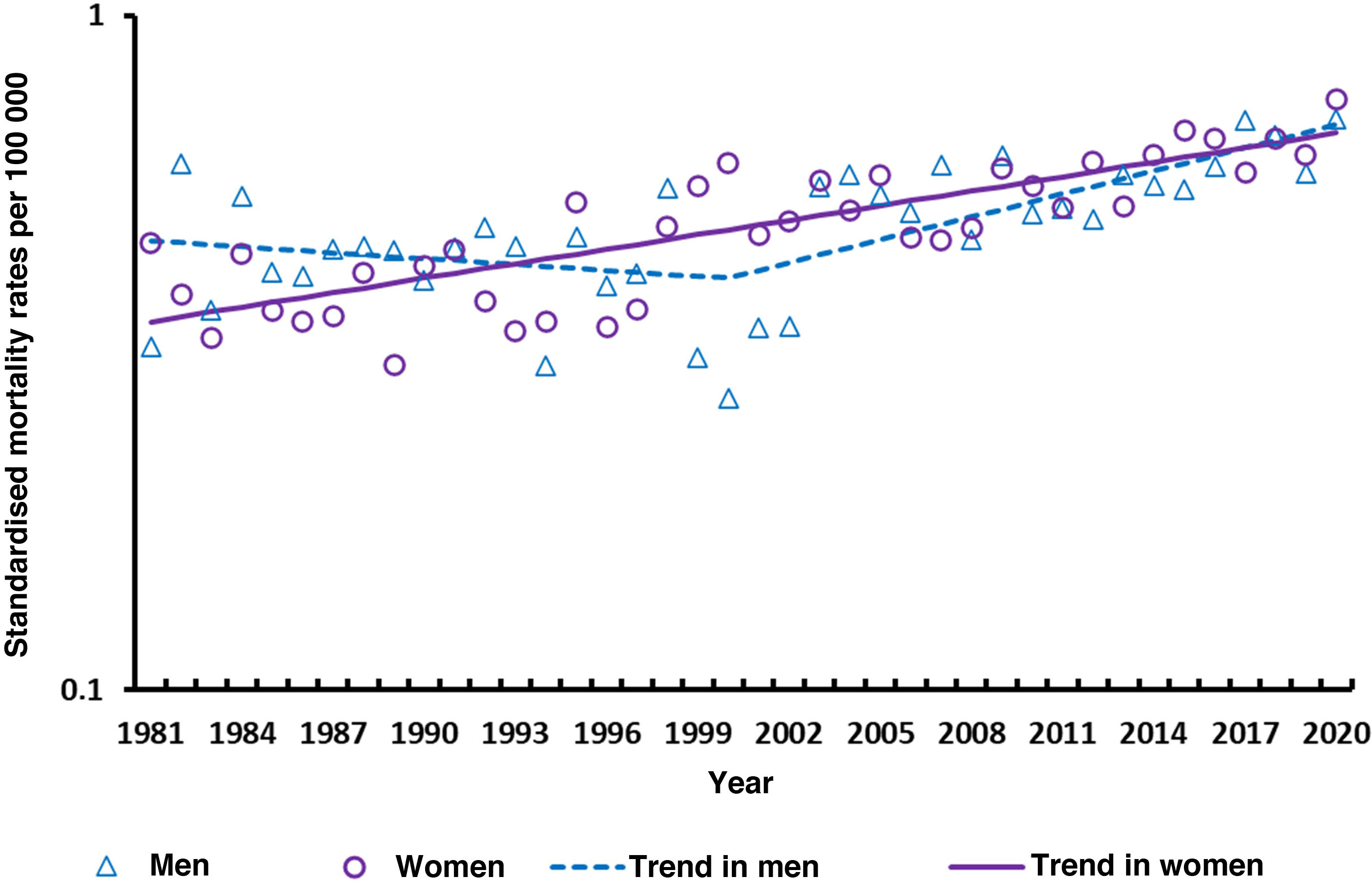

ResultsDuring the 40-year study period, we analysed 6940 deaths due to MS (3949 in women and 2991 in men, with a women-to-men ratio of 1.3:1). In men, we observed an annual 5% increase in the number of deaths (increasing from 39 in 1981 to 121 in 2021). In the case of women, we observed a similar increase, from 66 deaths in 1981 to 183 in 2020 (annual 4% increase). This trend is reflected in the ASMR, which significantly increases (P<.05) both in women and in men (average annual percentage change during the study period amounted to 1.7% in women and 1.2% in men). The joinpoint analysis did not show a trend change in women, but in the case of men it revealed a first period in which rates remained stable (1981–2000; annual percentage change: −0.7%, not significant), followed by a period of significant increase (2000–2020; annual percentage change: 2.6%, P = .05). (Fig. 1). ASMRs were very similar in men and women, with a women-to-men ratio of 1.0:1 (ranging from 0.6:1 in 1982 to 2.2:1 in 2000).

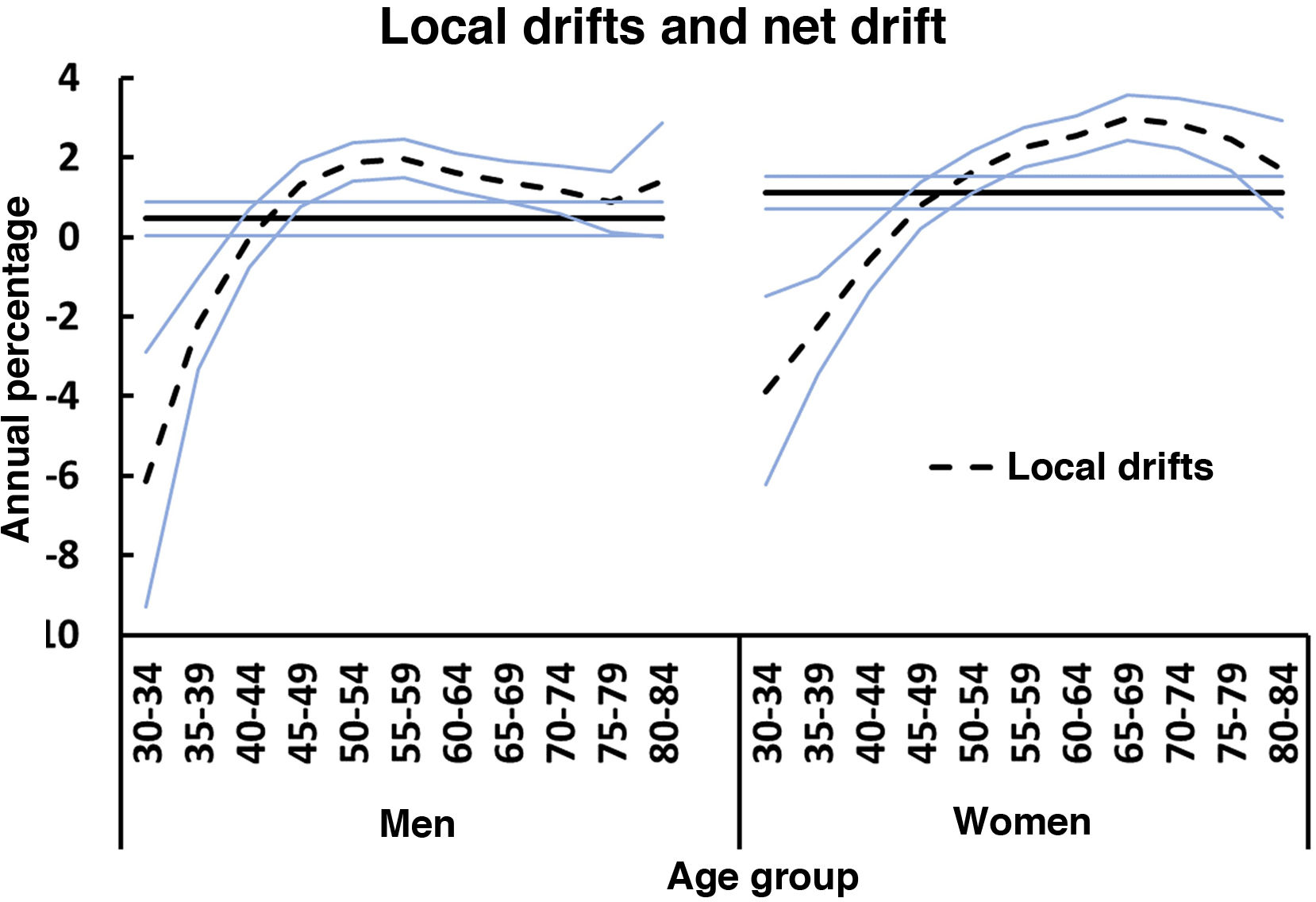

The net drift for the age groups included (30–84 years) amounted to 0.5% (P<.05) in men and to 1.1% (P<.05) in women. In both sexes, rates significantly decreased after the age of 40 years, and increased in patients aged older than 44 years. Rates in the 40-44 years age group remained stable during the study period. Fig. 2 shows the local drift, discriminated by sex, for each age group during the whole study period.

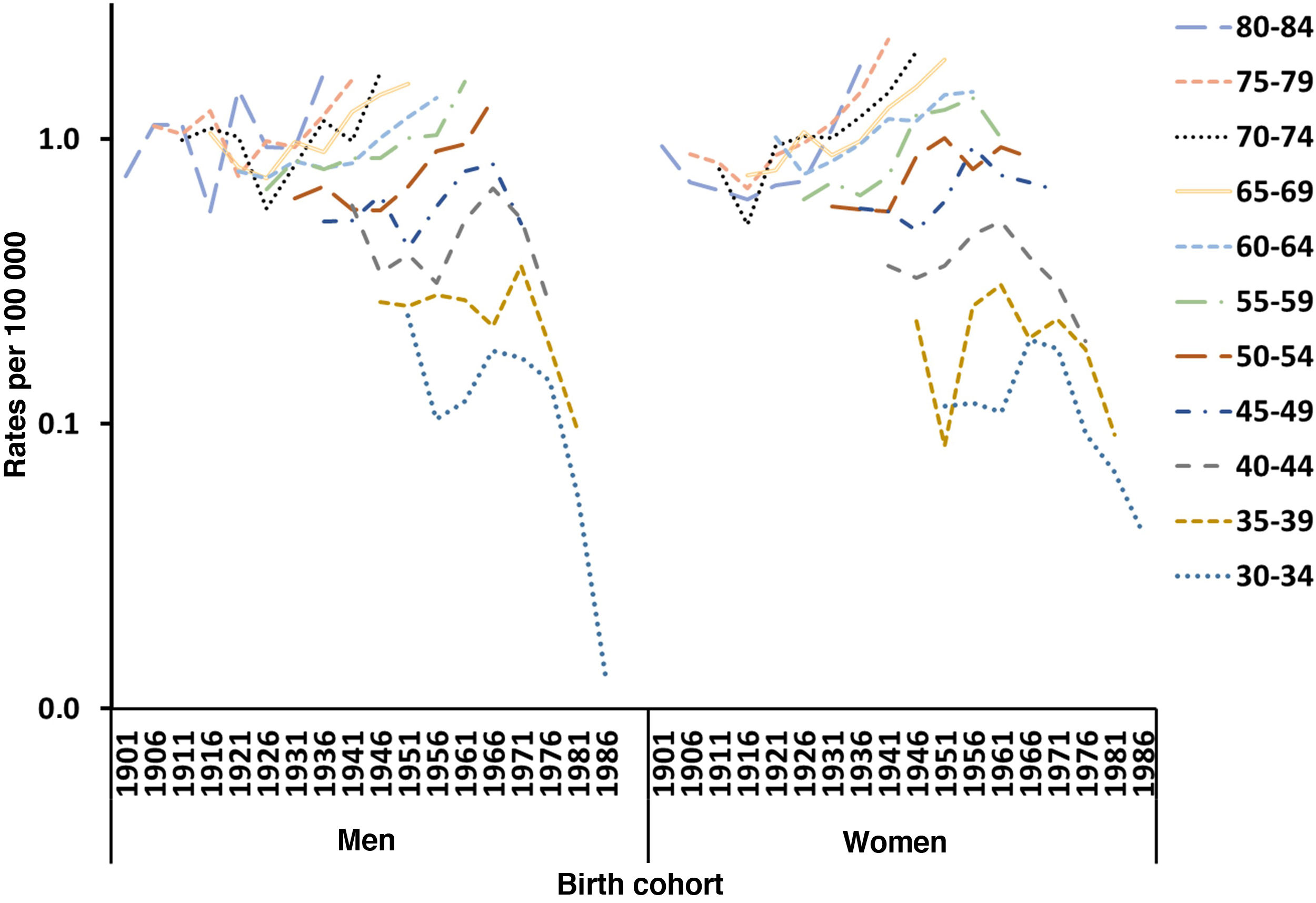

Fig. 3 shows the trends in mortality rates due to MS in men and women by age group according to the year of birth (1902–1987) in Spain. For both sexes, mortality rates per age cohort increased in older subjects, but decreased in younger age groups; however, this was only observed since the early 1960s in women and from the late 1970s in men.

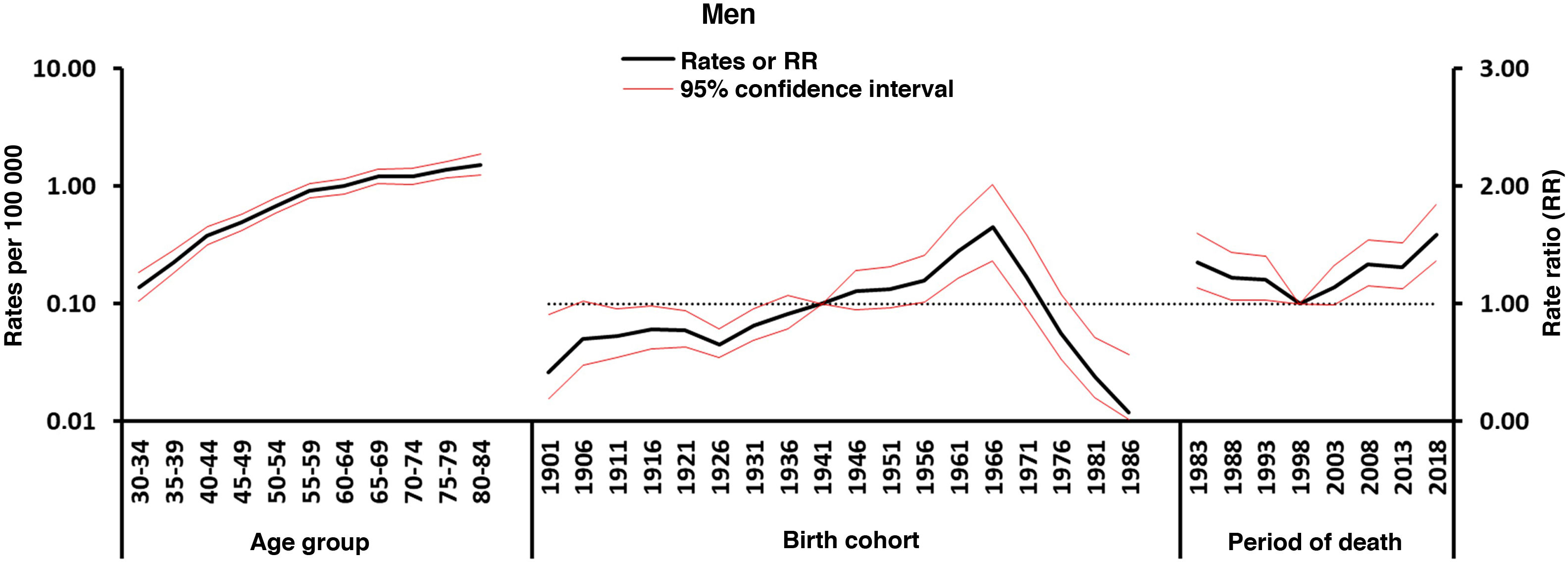

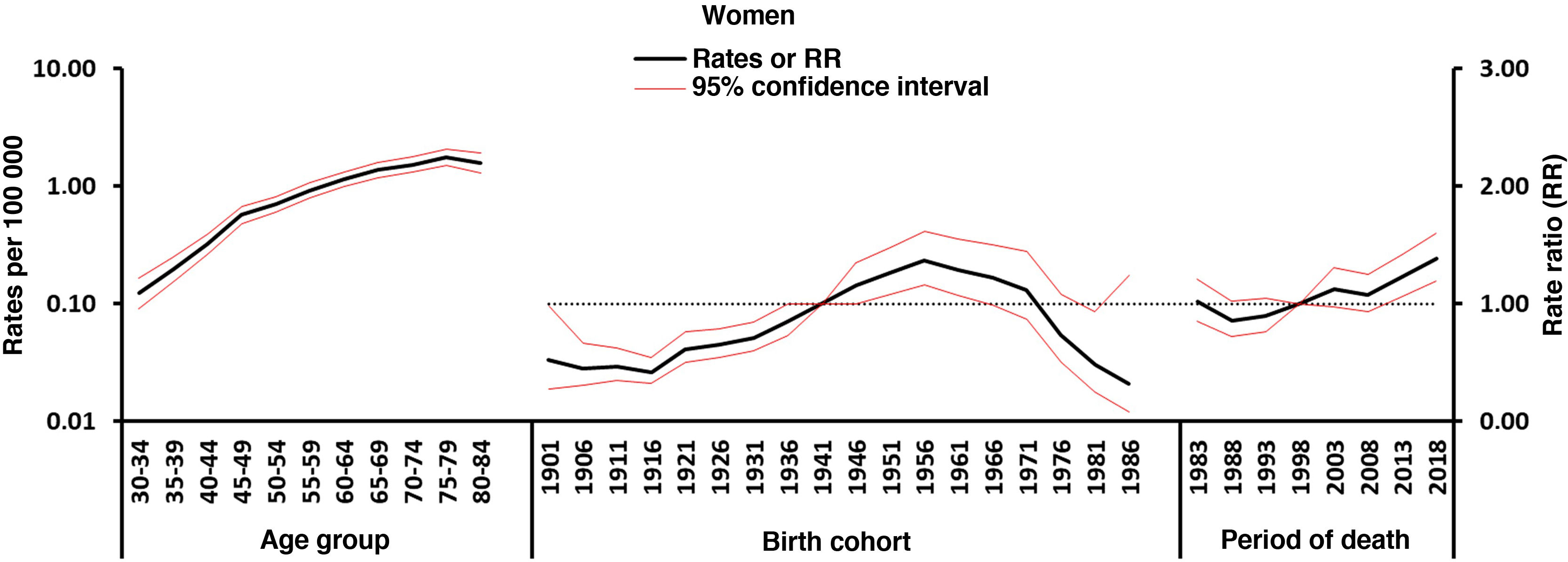

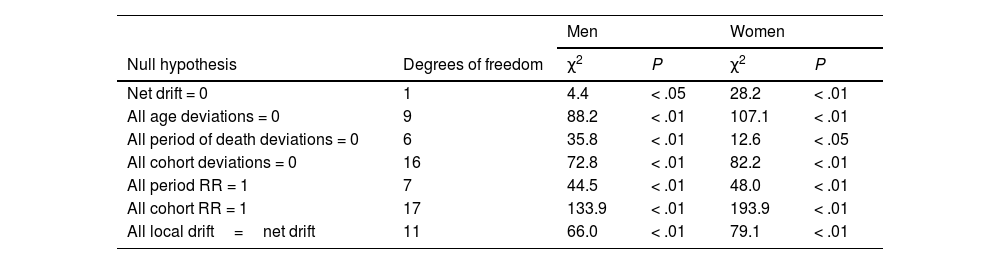

Figs. 4–5 show the findings obtained from the final APC model for each sex. The age effect (cross-sectional curve of age-specific mortality) is represented on a logarithmic scale, as specific rates increase exponentially in association with this variable and may be interpreted as the expected age-specific mortality rates in the reference period, adjusted for cohort effects. Period and cohort effects may be interpreted as age-specific rate ratios (RR) in each period or cohort with regard to the reference period or cohort. Cohort and period RRs were statistically significant in both sexes (P<.01), as were net drifts and local drifts (Table 1).

Wald chi-square tests for the estimable functions in the age-period-cohort model. Mortality due to multiple sclerosis in Spain, 1981-2020.

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null hypothesis | Degrees of freedom | χ2 | P | χ2 | P |

| Net drift = 0 | 1 | 4.4 | < .05 | 28.2 | < .01 |

| All age deviations = 0 | 9 | 88.2 | < .01 | 107.1 | < .01 |

| All period of death deviations = 0 | 6 | 35.8 | < .01 | 12.6 | < .05 |

| All cohort deviations = 0 | 16 | 72.8 | < .01 | 82.2 | < .01 |

| All period RR = 1 | 7 | 44.5 | < .01 | 48.0 | < .01 |

| All cohort RR = 1 | 17 | 133.9 | < .01 | 193.9 | < .01 |

| All local drift=net drift | 11 | 66.0 | < .01 | 79.1 | < .01 |

Regarding period effects, we observed a sustained increase in women from the beginning of the 1990s. In the case of men, we observed a pronounced increase since 1999, which was preceded by a stabilisation of risk in the previous years.

We identified an increase in mortality in association with birth cohort: women born from 1916 presented an increase in the risk of mortality due to MS, which reached its peak in 1956, and subsequently decreased. A similar pattern was observed in men, although one decade later (from 1926 to 1966).

DiscussionOur findings show a complete and updated analysis of the time trends in mortality due to MS in Spain, discriminated by sex and temporal components (age, period, and cohort). They show slight differences in rates and trends between men and women.

In Spain, although ASMRs showed a constant increase in both sexes over the past 2 decades, this trend was more pronounced in men. As in a previous study, ASMRs were very similar in both sexes.17

In the United States, mortality rates due to MS seem to have increased constantly between 1999 and 2015, regardless of sex.18 In Italy (1980–2015), a significant decrease in rates was observed between 1980 and 1995 in men and until 1999 in women. This decrease was followed by a significant increase in both sexes, which was more pronounced in women (1.9% and 2.3% in men and women, respectively).19

These trends may be due to age-associated changes to the risk of death due to MS (effects of age), changes in classifications of causes of death, short-term effects of diagnostic and treatment improvements made near the time of death that would decrease mortality due to MS (effects of period of death), and changes associated with the birth cohort (effects of birth cohort).

Age effectsWe observed a rapid increase in age-specific rates in both sexes (Fig. 5). The women-to-men ratio is approximately 1:1, and only in the 70-79 years age group did women present slightly higher rates than men (women-to-men ratio of 1.3:1). The higher mortality rates in the older groups are similar to those observed in other studies, and may be mediated by immunosenescence and the higher risk of infections, tumours, and autoimmune diseases at these ages.20

Effects of the period of deathThe effects of the period of death are usually associated with changes to the diagnosis and classification of the disease, which changed considerably during our study period. Our findings show a constant increase in both sexes, although with a delay of a decade in the case of men (Fig. 5), whose rates had previously been stable. In both cases, diagnosis of MS was only based on clinical findings, as until 2001 (the year that the McDonald criteria were adopted) no radiological or laboratory criteria were introduced. These criteria have been reviewed on several occasions, with the latest revision being published in 2017,21 which may have influenced the detection of cases (incidence and prevalence) and, therefore, in the mortality trends observed.22 Changes to MS diagnostic criteria in the past 25 years have led to an earlier diagnosis and to the onset of disease-modifying treatment (DMT) and have therefore decreased the risk of progression to disability.23 As patients usually live with MS for many years, factors contributing to the change in diagnostic accuracy may have existed prior to the changes to MS mortality. The increase in MS mortality in the past decades may be due not only to the increase in the prevalence of the disease, but also to the more widespread use of magnetic resonance imaging, which improves diagnostic accuracy even in older patients. However, it is possible that the increase in the detection of late-onset cases, due to the greater availability of magnetic resonance since 1995, may also be a contributing factor. In Spain, despite the introduction of DMT since the 1990s, earlier diagnosis, and improvements in patient care, we observed no improvements in MS mortality trends. On the contrary, we continue to observe an increase in mortality rates, independently of sex, in all age groups older than 49 years. The effect of DMT is probably hard to measure in older patients due to disease progression. A meta-analysis of clinical trials on MS supports the idea that age is an essential modifier of DMT efficacy, and suggests that there is no predicted benefit from receiving DMTs after the age of 53.24

The 9th and 10th revisions of the ICD may have an impact on the evolution of mortality trends. However, studies assessing the effects of the revisions of the ICD have reported good agreement between the ICD-9 and ICD-10 criteria on the classification of diseases.25

Cohort effectsCohort effects refer to the exposure throughout life to disease risk factors shared by a generation. The downward trend in MS mortality by birth cohort in men born since the mid-1960s and women born since the mid-1950s (Fig. 5), after an initial period of increase, is comparable with the findings obtained in APC analyses in other countries.

A study based on data from 25 countries during the period 1951-2009 found that estimations by birth cohort peaked in cohorts born in the first half of the 20th century, and divided countries into 5 groups.26 In a first group, including countries from Western and Central Europe, mortality rates peaked in birth cohorts from the 1920s. In a second group (Denmark, Sweden, Italy, Ireland, and Scotland), they peaked in birth cohorts from the 1920s and 1930s. A third group (Commonwealth countries, USA, and Norway) showed double or extended peaks starting in the 1910s or 1920s, and ending by the 1950s. A fourth group (Mediterranean countries and Finland) was characterised by a steady increase in rates among birth cohorts up to the 1950s. The fifth group, including countries from Eastern Europe and Japan, showed no particular pattern.

The increase in sex ratio in MS has been attributed to cohort effects, as women in more recent birth cohorts may have been more exposed or more vulnerable to environmental risk factors than men.27

Such environmental and lifestyle factors as vitamin D deficiency, smoking, and Epstein-Barr virus infection,28 which interact with genetic factors, may contribute to susceptibility and disease severity.29

A recent study (with data from the United Kingdom, Canada, Netherlands, Scotland, Switzerland, and the USA from 1951 to 2020) suggests that the similar patterns of mortality due to ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, Hodgkin lymphoma, and MS in the birth cohorts analysed may be due to the fact that these diseases may share a common environmental risk factor. This finding is similar to that reported in another study, suggesting that the patterns observed in the estimations of the cohort effect seem to indicate that the development of Crohn disease and MS would be conditioned by exposure to risk factors in the early stages of life.30 Such risk factors may include exposure to Epstein-Barr virus at young ages.

Smoking and obesity have harmful effects for the immune system and have been associated with MS activity and progression.31,32 The increase in MS incidence observed in Danish women between 1950 and 2009 has been attributed to a cohort effect linked to an age effect and effect of period of death associated with changes in women’s lifestyles, which may include fewer births and increased obesity and smoking.33

In Spain, men began smoking during the Civil War, and prevalence of smoking has decreased from the 1970s to today.34 In women, the prevalence of smoking began to increase in the 1960s and decreased from 2006 (although this decrease has been very slight), until current prevalence rates were reached.35 Obesity during the first years of life is significantly associated with an increased risk of MS.36 Furthermore, adipose tissue has recently been recognised as an active endocrine organ capable of inducing chronic inflammation through adipokines.37 In Spain, recent decades have seen an increase in the prevalence of obesity in almost all age and sex groups.38,39

This study presents several limitations derived from the data source used. As we lacked incidence data, we used mortality data from death certificates, which is the only data source available that meets coverage and continuity criteria.40 Mortality data are limited by the incomplete character of death records and the scarcity of the clinical data reported. Therefore, we did not perform stratified analyses by type of MS. However, this approach presents the advantage of including standardised data that have been routinely collected over a long period of time. Furthermore, although the limitations of epidemiological results based on mortality studies have been underscored, they nonetheless represent a basic element for understanding the disease and its determinants. Moreover, despite the statistical advantage of APC models, caution should be exercised when interpreting estimations, due to the known deficiencies of this model. In this regard, random variation in estimations of the classical parameters of the APC model (especially of the effects of younger cohorts, which are frequently modelled on small numbers) may lead to imprecise projections. In order to avoid this, we used only patients aged from 30 to 84 years.

Given the descriptive nature of APC analyses, we may only suggest possible aetiologies; otherwise, we may fall into the so-called ecological fallacy, whereby relationships identified in the data at the group level are assumed also to apply to individuals.41

ConclusionsIn Spain, ASMRs showed a constant increase in both sexes over the last 2 decades, although this was more pronounced in men. The downward trend by birth cohort for mortality due to MS in men born from the mid-1960s and in women born from the mid-1950s is similar to the findings obtained in APC analysis in other countries. This hidden epidemic suggests the presence of unknown but relevant underlying risk factors for MS.

What is already known about this subject?- -

Few studies have analysed MS mortality in Spain, and many of them present limitations, such as analysing only a specific region of the country or using only hospital records.

- -

We analysed the trends in mortality due to MS in Spain over a period of 40 years, using independent sex, age, period, and cohort effects.

- -

ASMRs for MS have increased in both sexes over the last 2 decades in Spain.

- -

Trends in birth cohorts have played a role in the change in MS risk in the 20th century in Spain, as has also been the case in other European countries.

- -

This hidden epidemic suggests the presence of unknown but relevant underlying risk factors for MS.

;1;

Author contributionsAll authors participated in the conception and design of the study; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting and critical review of the relevant intellectual content; and approval of the version to be published; and are responsible for guaranteeing that the questions associated with the accuracy and integrity of any part of the study are duly researched and resolved.

Ethical considerationsAs data obtained from the Spanish National Statistics Institute were anonymised in accordance with good clinical practice principles and the Declaration of Helsinki, and no patient was identified or any personal information accessed, this study did not require patient consent or approval by an ethics committee (Spanish Law 14/2007 of 3 July, on biomedical research, published in the Spanish Official Gazette on 4 July 2007 and available on PubMed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18201045/ [accessed 27 Feb 2023]).

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding the content of the study.