Coeliac disease (CD) is an enteropathy of autoimmune origin, triggered by the intake of foods containing gluten. The condition not only affects the digestive system, but also presents a broad clinical spectrum, including various neurological manifestations.1 Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, characterised by severe spinal cord and optic nerve involvement; it can be monophasic or display relapses and remissions, and is a cause of disability in young and adult patients.2 Given the limited published information on the relationship between these 2 entities, we decided to report the present case.

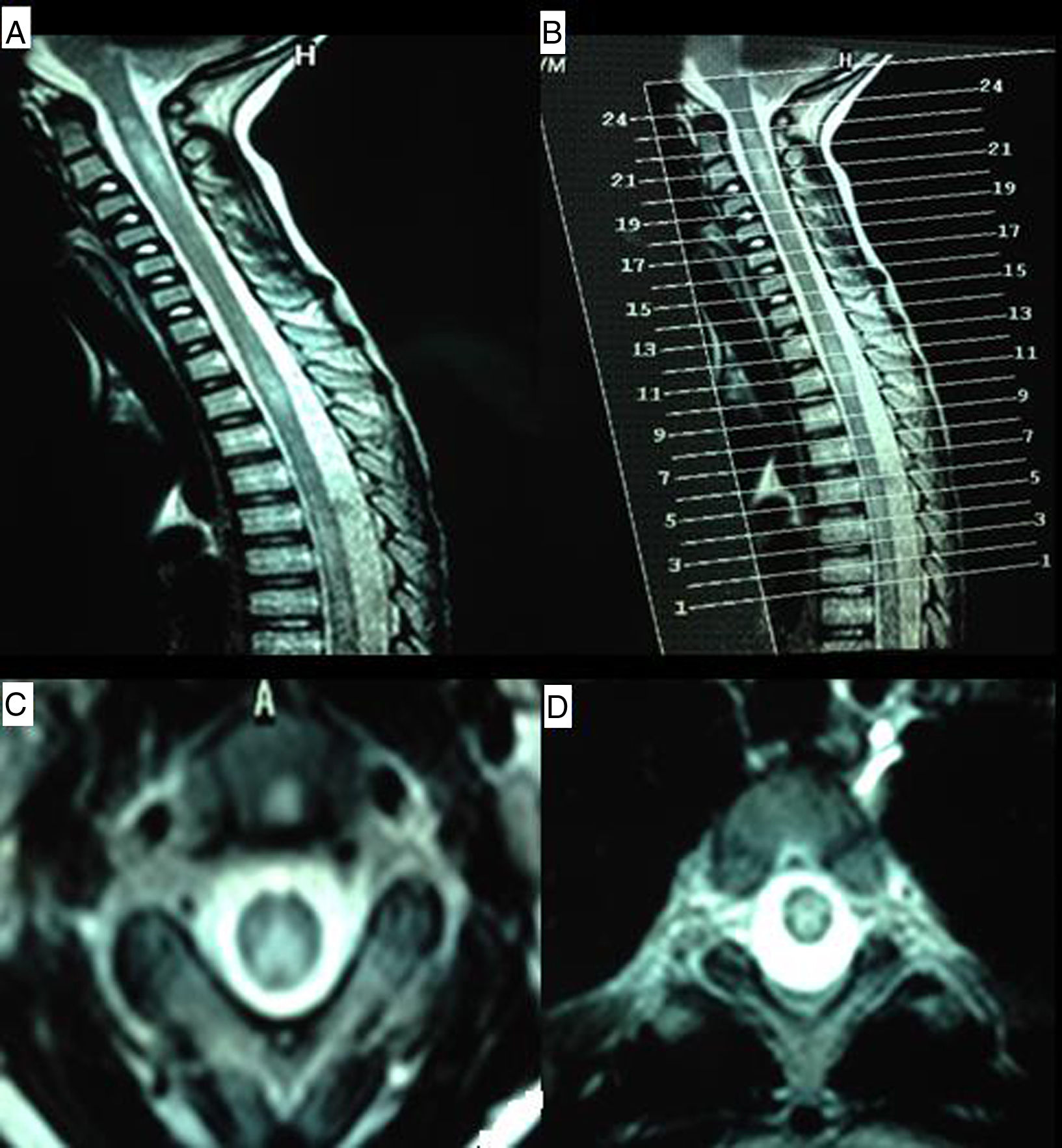

Our patient is a 9-year-old boy with a family history of CD (mother and a maternal aunt) and personal history of foetal distress, meningitis during lactation, severe sensorineural hearing loss diagnosed at 4 years and treated with cochlear implants, mild intellectual disability, and CD diagnosed at the age of 5. Diagnosis was based on high levels of anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies and anti-gliadin IgG and IgA antibodies, HLA-DQ2 expression, and compatible duodenal biopsy findings. He was admitted to hospital due to a 4-week history of subacute symptoms of lower limb pain and gait disorder with falls. During the examination the patient was alert and oriented, and displayed developmental delay with poverty of speech and dyslalias, visual deficit, and sensorineural hearing loss. He presented predominantly distal weakness of all 4 limbs, with generalised hyporeflexia, bilateral extensor plantar response, and no clear sensory alterations, although he did have difficulties completing the assessment. The patient displayed positive Romberg sign and difficulty toe and heel walking. The brain MRI scan was of little value due to the cochlear implants, but showed no significant alterations; a spinal MRI scan revealed increased signal intensity from C1 to T2, with patchy distribution and no contrast uptake (Fig. 1). We also requested analyses of lactate, ammonia, amino acids, and organic acids in the blood and urine; very long-chain fatty acids; phytanic, guanidinoacetic, and pristanic acids; alpha-fetoprotein; neuron-specific enolase; human chorionic gonadotropin; creatine; vitamins B12 and B6; folic acid; and immunoglobulins. An autoimmunity test and viral serologic testing were also performed. All results were normal. CSF study results were as follows: 8 cells, proteins 68mg/dL, glucose 60mg/dL, and weakly positive oligoclonal bands. An electromyography study showed signs of demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Visual evoked potentials revealed bilateral retrobulbar optic neuropathy. The study was expanded with tests for anti-NMO and anti-MOG antibodies, which yielded negative results. The patient was initially treated with immunoglobulins dosed at 0.4g/kg/day, with no response; he subsequently received methylprednisolone at 1g/day for 5 days, which achieved favourable outcomes. When interviewed, the mother admitted that the patient was not strictly following a gluten-free diet; in the absence of any other possible aetiology, NMO symptoms were attributed to CD. The patient was discharged and prescribed a tapered dose of the corticosteroid and a strict gluten-free diet. On 2 occasions over the following months, symptoms worsened in association with fever, and the patient was treated with corticosteroids, although radiology studies identified no new lesions; outcomes were excellent after resolution of the infectious symptoms.

MR images of the cervical and thoracic spine. (A) Sagittal T2-weighted sequence showing hyperintense lesions affecting the C1-C4 and T2-T4 regions. (B) Reference image for axial slices. (C) Axial T2-weighted sequence (slice 21) showing a hyperintense lesion predominantly affecting posterolateral regions of the spinal cord. (D) Axial T2-weighted sequence (slice 11) revealing a centrospinal hyperintense lesion.

Neurological complications are estimated to be present in 10% to 22% of cases of CD.3,4 Reported manifestations include ataxia, epilepsy, myopathy, migraine, cognitive impairment, and, as observed in our patient, axonal or demyelinating peripheral neuropathy, sensorineural hearing loss, and demyelinating diseases.1,5–7

The association between NMO and CD has very rarely been reported in the literature.8–13 Given that CD is relatively common, it would be difficult to demonstrate the cause of this relatively rare neurological syndrome. However, the excellent response to methylprednisolone and the introduction of a strict gluten-free diet suggest an inflammatory process in which gluten plays a fundamental role. Indeed, some authors have proposed that the pathophysiological mechanism may be an autoimmune process in which circulating IgG anti-neuronal antibodies target antigens in the central and enteric nervous systems.3,14

Our case highlights the importance of knowing the possible association between CD and NMO, as a strict gluten-free diet may positively affect both diseases.

Please cite this article as: Díaz Díaz A, Hervás García M, Muñoz García A, Romero Santana F, Pinar Sedeño G, García Rodríguez JR. Enfermedad celíaca y neuromielitis óptica: una rara pero posible relación. Neurología. 2019;34:547–549.