Adherence is a modifiable factor to disease-modifying treatments response in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Our objective is to assess the risk factors associated with inadequate adherence.

MethodRetrospective study through review of medical records and review of the database of pharmaceutical dispensing of patients with MS of a tertiary hospital from 2004 to 2022. A multivariate logistic regression analysis of demographic, clinical, nosological, and therapeutic factors was performed between adherent and non-adherent patients and treatments.

Result546 treatments of 284 patients (67.3% women, age 38.4 ± 10.0) were analysed, observing 87.5% adherence. Non-adherent patients presented a higher EDSS at the end of treatment, were more frequently patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, and had a higher proportion of cognitive impairment, psychiatric pathology, polypharmacy, and alcohol and drug use. After the multivariable analysis, risk factors were cognitive impairment (OR: 3.82 [1.51−9.70], P = .005), and alcohol and drug use (OR: 22.83 [7.32−71.20], P < .001). On the contrary, oral drugs favored better adherence (OR 0.29 [0.12−0.75], P = .01).

ConclusionsAmong many factors, alcohol or drug use and cognitive impairment are the major risk factors for low therapeutic adherence in patients with MS.

La adherencia es un factor modificable de respuesta a los tratamientos modificadores de la enfermedad en los pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM). Nuestro objetivo es valorar los factores de riesgo asociados a una inadecuada adherencia.

MétodoEstudio retrospectivo mediante revisión de historias clínicas y revisión de la base de datos de dispensaciones farmacéuticas de pacientes con EM de un hospital terciario desde 2004 hasta 2022. Se ha realizado un análisis de regresión logística multivariante de factores demográficos, clínicos, nosológicos y terapéuticos entre pacientes y tratamientos adherentes y no adherentes.

ResultadoSe analizaron 546 tratamientos de 284 pacientes (67.3% de mujeres, edad 38.4 ± 10.0), observándose un 87.5% de adherencia. Los pacientes no adherentes presentaron un mayor EDSS al final del tratamiento, eran más frecuentemente pacientes con esclerosis múltiple secundaria progresiva y tenían en mayor proporción deterioro cognitivo, patología psiquiátrica, polimedicación y consumo de alcohol y drogas. Tras el análisis multivariable resultaron factores de riesgo el deterioro cognitivo (OR: 3.82 (1.51−9.70), P = .005) y el consumo de alcohol y drogas (OR: 22.83 (7.32−71.20), P < .001). Por el contrario, los fármacos orales favorecieron una mejor adherencia (OR 0.29 (0.12−0.75), P = .01).

ConclusionesEntre numerosos factores, el consumo de alcohol o drogas y el deterioro cognitivo son los mayores factores de riesgo de baja adherencia terapéutica en pacientes con EM.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease whose control currently requires long-term treatment. The disease is frequent, affecting more than 2.3 million people worldwide, and severe, as it represents the most common non-traumatic cause of disability in young adults.1–3

Since 1994, multiple drugs have been approved for MS, many of which were approved in the past few years, showing ever-increasing efficacy.4 Since then, and until 2009, the only available treatments consisted of self-administered injectable drugs, interferons, and glatiramer acetate, which present modest efficacy and multiple side effects. Furthermore, several of these treatments must be administered frequently, with a considerable impact on patients’ daily life, which has been shown to be associated with poor adherence and decreased efficacy.5 For this reason, treatment adherence is considered one of the most important modifiable factors influencing a treatment’s effectiveness. Several studies have shown that poor adherence is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (higher rates of hospitalisations and relapses) and high healthcare costs.6–9

The degree of adherence to MS treatments ranges from 49% to 93%, depending on the study methodology used and the population analysed.10–15

Over the past 10 years, oral drugs have been marketed that are more convenient for patients and often show higher efficacy: fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, and teriflunomide.1 Furthermore, although the new treatments have shown higher adherence rates than previous injectable drugs,16–18 they are not free from adverse reactions or tolerance problems that may decrease patients’ adherence. This entails a need for new knowledge regarding the epidemiology of adherence to these new treatments. Furthermore, such other factors as age, sex, disability, progression time, number of previous treatments, polymedication, and the presence of depression or psychiatric alterations also influence adherence, decreasing the efficacy of these drugs.19–22

Our study aims to analyse the degree of adherence to the different drugs used for MS at our hospital, as well as the factors influencing the course of the disease.

Material and methodsWe analysed dispensing and adherence data on the self-administered treatments dispensed by the pharmacy department at Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada between January 2004 and January 2022, and used for at least 2 months. We included the following treatments: intramuscular interferon beta 1a, subcutaneous peginterferon beta 1a, subcutaneous interferon beta 1a at 22 and 44 μg, interferon beta 1b, glatiramer acetate at 20 and 40 mg/mL, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod. We excluded treatments administered by healthcare staff (intravenous administration).

Treatment adherence was defined as the number of days using the dispensed medication divided by the total days from onset to the end of the treatment period. Non-adherence was defined as a period in which the patient did not take > 80% of the doses calculated between dispensing events (that is, they collected their medication late), when patients stopped collecting their medication, and when patients’ clinical records stated that they were not taking the medication during the corresponding dispensing period despite having collected it regularly. This independent variable was considered dichotomous (yes or no). This information was obtained through the dispensing records of the hospital pharmacy department and by reviewing the electronic medical records of all patients.

The dependent variables gathered included: sex, age at the beginning of the study period, type of MS, treatments and administration routes, treatment status (new or switch), previous treatments, treatment duration in days and weeks, relapses before and during the treatment, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score at treatment onset and end, change in EDSS score during treatment, clinical progression (increase of 1 or more points in the EDSS score during treatment), presence of cognitive impairment (score ≥ 1 on the EDSS cognitive subscale), diagnosis of concomitant psychiatric disease requiring medication or therapy, number of drugs taken per day (other than the drug analysed), polymedication (5 or more drugs in addition to the drug analysed), and consumption of alcohol or other toxic substances.

To increase data consistency, we only analysed treatments lasting more than 2 months.

A database was created using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, which included the treatment used by each patient, adherence, and the above-mentioned corresponding dependent variables, adjusted to the patient’s situation at all times.

Statistical analysisQualitative data were described as absolute frequencies and percentages, and quantitative data as means (standard deviation [SD]), medians, and range.

Qualitative variables were analysed with the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test, and quantitative variables with the t test or non-parametric tests to compare between the 2 groups of patients. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05. We developed a stepwise multivariate logistic regression model to study factors associated with non-adherence. This model included variables that, considering the sufficient number of cases, presented a statistical significance level ≤ .20 in the univariate analysis. Data were retrospectively included in a database (Microsoft Excel 2019) and analysed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS Inc.).

ResultsWe obtained dispensing data on a total of 549 treatments; 3 were removed from the analysis due to lack of data. The 546 treatments analysed corresponded to 295 patients.

At the time of the first observation, that is, at the time when the patient received the first treatment, the mean age (SD) was 36.9 (9.8), with women accounting for 67.1% of patients (198/295). At that time, 7.8% of patients had clinically isolated syndrome (CIS),23 80.3% (237) had relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), and 11.9% (35) had secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS). Psychiatric disease was present in 28.1% of patients (83), polymedication in 8.8% (26), and consumption of alcohol and toxic substances in 4.7% (14). Cognitive impairment was recorded in 12.9% of patients (38). The rate of adherence amounted to 85.4% (252/295). Mean EDSS score was 2.29 (1.39). The mean duration of the first treatment was 3.5 (3.12) years.

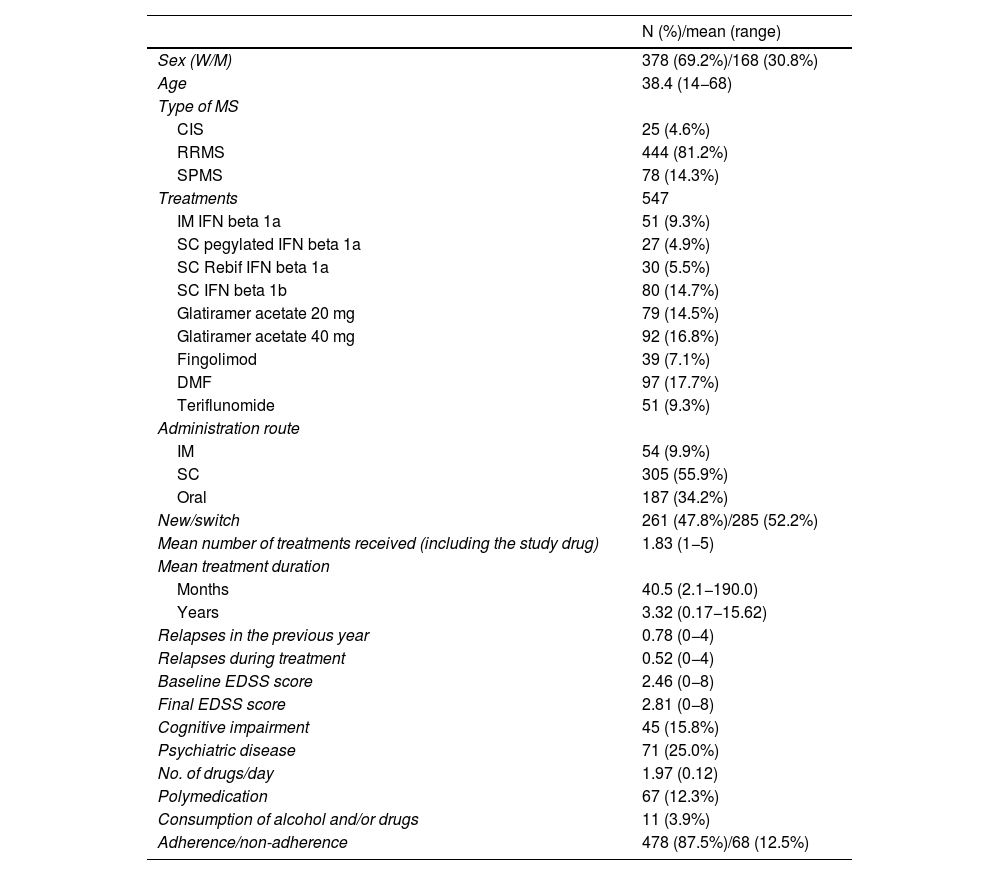

The characteristics of the treatments analysed (including all the treatments received by the patients and the first treatment received) are shown in Table 1 and described below.

Characteristics of the patients and treatments analysed.

| N (%)/mean (range) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (W/M) | 378 (69.2%)/168 (30.8%) |

| Age | 38.4 (14−68) |

| Type of MS | |

| CIS | 25 (4.6%) |

| RRMS | 444 (81.2%) |

| SPMS | 78 (14.3%) |

| Treatments | 547 |

| IM IFN beta 1a | 51 (9.3%) |

| SC pegylated IFN beta 1a | 27 (4.9%) |

| SC Rebif IFN beta 1a | 30 (5.5%) |

| SC IFN beta 1b | 80 (14.7%) |

| Glatiramer acetate 20 mg | 79 (14.5%) |

| Glatiramer acetate 40 mg | 92 (16.8%) |

| Fingolimod | 39 (7.1%) |

| DMF | 97 (17.7%) |

| Teriflunomide | 51 (9.3%) |

| Administration route | |

| IM | 54 (9.9%) |

| SC | 305 (55.9%) |

| Oral | 187 (34.2%) |

| New/switch | 261 (47.8%)/285 (52.2%) |

| Mean number of treatments received (including the study drug) | 1.83 (1−5) |

| Mean treatment duration | |

| Months | 40.5 (2.1−190.0) |

| Years | 3.32 (0.17−15.62) |

| Relapses in the previous year | 0.78 (0−4) |

| Relapses during treatment | 0.52 (0−4) |

| Baseline EDSS score | 2.46 (0−8) |

| Final EDSS score | 2.81 (0−8) |

| Cognitive impairment | 45 (15.8%) |

| Psychiatric disease | 71 (25.0%) |

| No. of drugs/day | 1.97 (0.12) |

| Polymedication | 67 (12.3%) |

| Consumption of alcohol and/or drugs | 11 (3.9%) |

| Adherence/non-adherence | 478 (87.5%)/68 (12.5%) |

CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; DMF: dimethyl fumarate; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; IFN: interferon; IM: intramuscular; M: men; MS: multiple sclerosis; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SC: subcutaneous; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; W: women.

Patients were mainly women (69.2%), with a mean age (SD) of 38.4 (10.0) years (range, 14−68). A total of 81% presented RRMS, whereas 14% had SPMS and only 4% had CIS. The mean (SD) EDSS score was 2.02 (0.99), with a median score of 2.0 in patients with RRMS; 4.69 (1.66), with a median score of 4.75 in patients with SPMS; and 1.58 (0.66), with a median score of 1.5 in patients with CIS. The majority of treatments analysed were injectable drugs (66%) and the percentage of new treatments vs treatment switches amounted to 48% vs 52%. The majority of patients had received more than one treatment (mean of 1.83). Regarding treatment duration, Tables 1 and 2 show the duration of treatments in the total sample, and in adherent and non-adherent patients. These results take into account the duration of the treatments analysed until the database was closed; mean duration of treatment amounted to 3.32 (2.6) years. Of the treatments analysed (546), only 396 (75.2%) treatments were completed, whereas 150 (27.4%) were still ongoing at the time of the analysis. The duration of completed treatments amounted to 3.01 (2.5) years. Duration was 2.82 (2.34) years in adherent patients, and 4.12 (3.09) years in non-adherent patients.

Study outcomes.

| Adherent patients (n = 478) | Non-adherent patients (n = 68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age | 38.58 (9.94); 38 (54) | 37.82 (10.44); 36 (45) | ns |

| Women/men | 336/142 | 42/26 | .154 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Baseline EDSS score | 2.49 (1.39); 2 (8) | 2.77 (1.68); 2.5 (7.5) | .060 |

| Final EDSS score | 2.72 (1.65); 2 (7.5) | 3.49 (1.95); 3.0 (8.0) | < .001 |

| Progression (ΔEDSS) | 0.3 (0.77); 0 (6) | 0.72 (0.95); 0.5 (5.5) | < .001 |

| Progression (ΔEDSS ≥ 1) | 96 (20.1%) | 24 (35.3%) | .007 |

| Relapses in the year prior to treatment | 0.77 (0.65); 1 (4) | 0.87 (0.67); 1 (3) | ns |

| Relapses during treatment | 0.51 (0.72); 0 (4) | 0.65 (0.75); 1 (3) | .141 |

| Type of MS | |||

| RRMS | 394 (82.3%) | 50 (73.5%) | .085 |

| SPMS | 63 (13.2%) | 15 (22.1%) | .049 |

| CIS | 22 (4.6%) | 3 (4.4%) | ns |

| Cognitive impairment | 54 (11.3%) | 28 (41.2%) | < .001 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 129 (26.9%) | 37 (54.4%) | < .001 |

| Polymedication | 52 (10.9%) | 15 (22.1%) | .008 |

| No. of drugs per day | 1.87 (2.03); 1 (12) | 2.66 (2.88); 2 (12) | .005 |

| Consumption of alcohol or drugs of abuse | 5 (1%) | 20 (29.4%) | < .001 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Treatment duration (years) | 3.19 (2.69); 2.45 (15.56) | 4.22 (3.22); 3.3 (12.92) | .004 |

| New | 225 (47.0%) | 36 (52.9%) | ns |

| Switch | 253 (53.0%) | 32 (47.1%) | ns |

| No. of treatments for MS | 1.86 (1.00); 2 (4) | 1.66 (0.84); 1 (3) | .127 |

| Treatment | |||

| IM IFN beta 1a | 42 (82.4%) | 9 (17.6%) | ns |

| SC pegylated IFN beta 1a | 23 (85.2%) | 4 (14.8%) | ns |

| SC Rebif IFN beta 1a | 24 (80%) | 6 (20%) | ns |

| SC IFN beta 1b | 65 (81.3%) | 15 (18.8%) | ns |

| Glatiramer acetate 20 mg | 63 (79.7%) | 16 (20.3%) | ns |

| Glatiramer acetate 40 mg | 82 (89.1%) | 10 (10.9%) | ns |

| Teriflunomide | 49 (96.1%) | 2 (3.9%) | ns |

| DMF | 92 (94.8%) | 5 (5.2%) | ns |

| Fingolimod | 38 (97.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | ns |

| Administration route | |||

| Subcutaneous | 255 (53.2%) | 51 (75.0%) | .001 |

| Intramuscular | 45 (9.4%) | 9 (13.2%) | ns |

| Oral | 178 (37.1%) | 8 (11.8%) | < .001 |

Data are expressed as either number (%) or mean (SD) plus median (range).

CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; DMF: dimethyl fumarate; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; IFN: interferon; IM: intramuscular; MS: multiple sclerosis; ns: not significant; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SC: subcutaneous; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

The annualised relapse rate was 0.78 in the year prior to each treatment and 0.52 during treatment. Mean EDSS score before treatment amounted to 2.46, vs 2.81 at the end of treatment. In our series, 15% of the patients presented cognitive impairment and 25% psychiatric disorders.

Polymedication was reported by 12.2% of patients, and mean treatment duration was 1.97 years. During treatment for MS, 4.7% of patients reported abusive consumption of alcohol or toxic substances.

Adherence was observed in 87.6% of the treatments analysed (479 treatments with adherence rates above 80% and 68 treatments with lower adherence rates).

Comparison of patient characteristics during periods of treatment adherence and non-adherence (Table 2) revealed no significant differences regarding sex (percentage of women: 70.3% vs 61.8%; P = .151) or age (38.6 vs 37.3 years, not significant). Neither did we observe significant differences in baseline EDSS score (2.49 vs 2.77; P = .06), although the final EDSS score was significantly poorer in non-adherent patients than in those adhering correctly to their treatment (2.72 vs 3.49; P < .001). When calculating progression as the difference between baseline and final EDSS scores, we observed significant differences: mean progression amounted to 0.3 (0.77) in adherent patients and 0.72 (0.95) in non-adherent patients (P < .001).

The previous relapse rate also showed no significant differences (0.77 vs 0.87). Furthermore, non-adherent patients showed a higher mean relapse rate during treatment than adherent patients (0.65 vs 0.51), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = .141). Regarding the type of MS, the percentage of SPMS among non-adherent patients was significantly higher than in non-adherent patients (22% vs 13%, P = .049).

The percentage of patients with cognitive impairment was significantly higher among non-adherent patients (41.2% vs 11.3%; P < .001); this was also the case with psychiatric disorders (54.4% vs 26.9%; P < .001). Patients with MS and psychiatric disease presented depression (43/71), anxiety (12/17), psychotic disorders (7/71), conversion disorder (5/71), bipolar disorder (1/71), and other disorders (8/71).

We also observed a greater number of patients with polymedication among non-adherent patients than in adherent patients (22.1% vs 10.9%; P = .008), as well as a significant difference in the mean number of different treatments used (2.66 in non-adherent patients vs 1.87 in adherent patients; P = .005). Consumption of alcohol or other toxic substances was strongly correlated with non-adherence (29.4% vs 1%; P < .001). Substances included alcohol (6/11), cocaine (3/11), cannabis (2/11), and opioids (1/11).

Regarding treatment characteristics, we observed no differences in treatment status (new or switch) or in the number of previous treatments. We did observe significant differences in the administration route: non-adherent patients received a significantly higher percentage of subcutaneous drugs (75% vs 53%; P = .001), and a significantly lower percentage of oral drugs (11.8% vs 37.1%; P < .001). We observed no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients receiving intramuscular treatments (13.2% vs 9.4%). Fig. 1 shows an improvement in adherence rates with the increase in the use of oral drugs.

The multivariate analysis (Table 3) showed that consumption of alcohol or other toxic substances increased the risk of non-adherence by up to 22 times (odds ratio [OR] 22.83; P < .001), and the presence of cognitive impairment by up to 3 times (OR: 3.82; P = .005). A higher EDSS score at treatment onset also slightly increased the risk of non-adherence (OR: 1.63; P = .023). On the other hand, a higher EDSS score at the end of treatment protected against non-adherence (OR: 0.58; P = .009). However, no statistically significant difference was observed for the variable progression (yes or no) (OR: 0.37; P = .08), despite its acting as a protective factor.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regression model of factors associated with treatment adherence.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.13 | 0.57−2.24 | .724 |

| EDSS score at treatment onset | 1.63 | 1.07−2.49 | .023 |

| EDSS score at the end of treatment | 0.58 | 0.39−0.87 | .009 |

| Progression | 1.2 | 0.582−2.46 | .63 |

| Relapses during treatment | 1.10 | 0.69−1.73 | .694 |

| Cognitive impairment | 3.82 | 1.51−9.70 | .005 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1.56 | 0.75−3.24 | .233 |

| Polymedication | 1.65 | 0.65−4.18 | .287 |

| Consumption of alcohol or drugs of abuse | 22.83 | 7.32−71.20 | < .001 |

| Treatment duration | 1.00 | 1.0−1.0 | .203 |

| No. of treatments for MS | 1.16 | 0.78−1.74 | .460 |

| Oral route | 0.29 | 0.12−0.75 | .010 |

| Type of MS (SPMS) | 0.72 | 0.90−1.14 | .396 |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS: multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

The use of oral treatments protected against non-adherence (OR: 0.29; P = .01).

For the remaining factors, although no statistically significant differences were identified, an increased risk of non-adherence was observed in patients with psychiatric disease (OR: 1.56; P = .23) and polymedication (OR: 1.65; P = .287). Regarding the type of MS, RRMS was also observed to protect against non-adherence, although the difference was not statistically significant (OR: 0.32; P = .078).

DiscussionOur population’s baseline characteristics coincide with those of the majority of studies, with a predominance of women (67.1%) and a mean age of 36.9 years. More than 80% of patients had RRMS, with CIS representing a very low percentage that decreased over time; this is logical, considering the study period (2004–2021). Furthermore, there were changes in diagnostic criteria: from 2017, the majority of patients with a single relapse were diagnosed with MS based on MRI findings and oligoclonal band study. More than half of the treatments supplied (52%) were treatment switches, and patients had received a mean of 2 treatments. This is explained by the increasing availability of therapies for MS, which in recent years has led patients to switch treatment frequently, considering not only effectiveness but also convenience for the patient. However, due to the long study period, the majority of treatments analysed (66%) were injectable drugs, although in the last few years most treatments were administered orally, with many patients changing to this administration route due to its convenience and better general tolerance.

In our series, the adherence rate is very high (87.6%), higher than that expected in the general population but in line with the rates reported in some studies on MS,10,13 although higher than in the majority of studies.14 We believe that this high adherence rate is due to the homogeneous series of patients treated at the same hospital, at which a hospital pharmacy department is available and offers in-person consultations to supervise the dispensing of medications on an individual basis and control for treatment non-adherence. A home delivery dispensing service has also been implemented for those patients who may need it. However, the differences observed in adherence may also be due to the different data collection methods used. In our study, we aimed to identify the profile of the non-adherent patient, without considering the adverse effects caused by treatments; therefore, we did not analyse those treatments lasting less than 2 months.

Regarding factors influencing treatment compliance, unlike in other studies showing greater adherence in men than in women,9,13,15 we observed the opposite in our series (adherence in 88.9% of women and 84.5% of men), although this difference was not statistically significant. We did not observe an influence of age on adherence, despite reports from some previous studies that younger patients present a higher risk of poor treatment compliance.9,13,15 Furthermore, the presence of relapses in the year prior to the onset of treatment showed no differences between groups.

Baseline EDSS scores were slightly higher in the group of non-adherent patients (2.49 [1.39] in adherent patients vs 2.77 [1.68] in non-adherent patients). Final EDSS scores and changes in EDSS score during treatment revealed significant differences, with the EDSS score being much higher in non-adherent patients than in adherent patients (2.72 [1.65] vs 3.49 [1.95]), and larger differences in EDSS scores between the beginning and the end of treatment; therefore, we may associate poor adherence with poorer progression. However, it is also plausible that patients who are showing disease progression and a higher EDSS score at the end of treatment might present better adherence, as the multivariate analysis has shown. Our interpretation is that non-adherent patients may present a poorer progression, but the inverse association is not shown: patients with disease progression are not more likely to show non-adherence.

Regarding treatment duration, the values reported may be considered somewhat low (approximately 3 years; Tables 1 and 2) with shorter treatment duration in adherent patients than in non-adherent patients. We believe that this finding may be influenced by the use of bridging therapies used in special situations such as pregnancy or comorbidities. In these situations, treatment durations were shorter than the mean and patients showed adherence.

Contrary to the findings of other studies,10 we did not observe a higher risk of non-adherence in patients with treatment switches than in those who maintained the initial treatment. The mean number of previous treatments was also not associated with poorer treatment compliance. Treatment duration was significantly higher in non-adherent patients than in adherent patients; this has also been described in other series,10 although it is difficult to explain in clinical terms.

Regarding the clinical form of the disease, patients with SPMS showed a tendency toward poorer adherence, which could not be confirmed in the multivariate analysis, contrary to other studies.16,17 This may be explained by the limited efficacy of treatments in this type of MS, in addition to the patient’s perception of lack of treatment effectiveness,18 and the adverse effects of the drugs used at the time of such studies. We consider that the lack of a significant association between type of MS and non-adherence when compared with other variables is influenced by the use of oral drugs since 2012.

The presence of cognitive impairment was strongly correlated with poor compliance in our population. The multivariate analysis showed that the risk of non-adherence was nearly 4 times greater in patients with cognitive symptoms. This has been observed in the majority of studies analysing this subject.14 In some prospective studies, patients reported “forgetfulness” as the main cause for missed doses.19 Furthermore, as the majority of treatments analysed were injectable, cognitive problems may logically cause errors when handling the pens and devices used for drug administration. Psychiatric comorbidities were another factor showing a significant association with poor adherence in our study. A 2010 prospective study revealed that patients with mood disorders and anxiety present up to 5 times greater risk of not adequately complying with therapy,20 which has also been observed in observational retrospective studies similar to our own.16,19

Polymedication was also associated with poor compliance in our series, with the number of other concomitant treatments being significantly higher in non-adherent patients than in adherent patients (2.66 vs 1.87). This finding had also been described in other studies,20–22 and may be explained by the complexity of the treatment schedule and the foreseeable multiplication of side effects in patients using multiple drugs, which may lead them to cease administering some of them.

The administration route has been described as a determinant factor in adherence in multiple recent studies performed since oral drugs became available,13,14,21,23 with injectable drugs being associated with poorer compliance (up to 50% lower adherence in some series).13 In our study, compliance with oral medications was significantly better; this is somewhat unsurprising, as they are associated with increased convenience and satisfaction for the patient, which are factors that, when analysed prospectively, favour adherence.10 In our study, we observed no differences between the different administration routes of injectable drugs, even though subcutaneous formulations require more frequent administration than intramuscular formulations; in several series, this higher frequency is associated with more missed doses.13,23 However, considering the time period analysed, we observed a progressive decrease in non-adherence as the use of oral drugs expanded at the expense of injectable drugs.

Harmful consumption of alcohol or other toxic substances was strongly associated with poor compliance. Among non-adherent patients, a very high percentage (29%) reported abusive consumption of these substances. More than 90% of these patients were men receiving injectable drugs. After the multivariate analysis, we observed that abusive consumption of toxic substances, including alcohol, was associated with more than 20 times greater risk of not adequately complying with treatment. A previous study also reported that abusive consumption of alcohol increased the risk of missing multiple doses by up to 14 times22; we have not found any other series exploring the influence of other toxic substances on adherence to MS treatments. This finding is relevant, as the use of toxic substances is more frequent in younger populations, such as patients with MS; on many occasions, this fact is not spontaneously reported by patients. Given the strong correlation with non-adherence, this may represent a very important element in the control of the disease.

Our study presents certain limitations: we did not analyse the adverse effects of the treatments studied or the individual reasons for treatment switches. Furthermore, we did not analyse adherence to intravenous or recently used treatments, such as ponesimod, ozanimod, or ofatumumab. This is a retrospective study, and we were not able to quantify some of the variables analysed; for example, we did not quantify the consumption of alcohol, as has been done in another study.22

However, considering the long period analysed, we may conclude that such factors as high EDSS scores, cognitive impairment, and consumption of toxic substances entail an increased risk of problems with treatment adherence. Unfortunately, these problems will persist in the future, despite pharmacological advances. Therefore, we consider multidisciplinary work and psychosocial support to be highly relevant in the care of these patients.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

We would like to thank Pedro Fernández de Córdoba Cascales for his support in managing digital data and Eva Alonso Corzo for her contribution in creating figures and tables.