Real-world data studies are a promising option for understanding everyday Parkinson's disease (PD) management and optimizing strategies and therapeutic options. The Parkinson's Real-World Impact Assessment (PRISM) project was conceived as a European survey to evaluate the burden of the disease in people with Parkinson's disease (PwP) and their caregivers. Here, we present the analysis of the Spanish PRISM cohort dataset to describe prescribing patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and the impact of PD on PwP and their caregivers.

MethodsData were collected using an electronic questionnaire distributed through different patient advocacy groups and specialized PD clinics in Spain.

ResultsA total of 149 PwP (mean age, 62.6 years; mean disease duration, 7.6 years) and 38 caregivers were included. Most PwP (87.1%) received levodopa during the 12 months preceding the survey. A high percentage of patients (62.1%) expressed interest in participating in a clinical trial, but only 20% reported a current or previous enrollment. PwP reported high incidence of non-motor symptoms and poor health-related quality of life. At least one impulse control behavior was reported in 57% of patients. Caregivers reported mild to moderate disease burden.

ConclusionsThis study identified high rates of motor and non-motor symptoms, impulse control disorders, and considerable disease burden in PwP and their caregivers, even at a relatively young age and a mild/moderate stage of the disease. Also, it highlights the limited use of rehabilitation therapies. These data provide information for PD management and resource utilization in Spain.

Los estudios de vida real son una opción prometedora para comprender el manejo cotidiano de la enfermedad de Parkinson (EP) y optimizar estrategias y opciones terapéuticas. El estudio Parkinson's Real World Impact Assessment – PRISM – se planteó como una encuesta europea para evaluar la carga de la enfermedad en personas con EP y en sus cuidadores. Aquí presentamos el análisis de datos de la cohorte española de PRISM para describir los patrones de prescripción, el uso de recursos sanitarios y el impacto de la EP en los pacientes y sus cuidadores.

MétodosLos datos se recopilaron mediante un cuestionario electrónico distribuido a través de diferentes asociaciones de pacientes y clínicas especializadas en EP en España.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 149 pacientes (edad media, 62,6 años; duración media de la enfermedad, 7,6 años) y 38 cuidadores. La mayoría de los pacientes (87,1%) recibió levodopa durante los 12 meses previos a la encuesta. Un alto porcentaje de pacientes (62,1%) expresó interés en participar en un ensayo clínico, pero solo el 20% indicó estar actualmente inscrito o haberse inscrito en el pasado en un ensayo. Los pacientes informaron una alta incidencia de síntomas no motores y de una calidad de vida relacionada con la salud deteriorada. El 57% de los pacientes informó de al menos un comportamiento asociado a trastornos del control de impulsos. Los cuidadores informaron de una carga de enfermedad leve a moderada.

ConclusionesEste estudio identificó altas tasas de síntomas motores y no motores, trastornos de control de impulsos y una carga de la enfermedad significativa en personas con EP y en sus cuidadores, incluso cuando los pacientes tienen una edad relativamente joven y en una etapa leve/moderada de la enfermedad. Además, destaca el uso limitado de terapias de rehabilitación. Estos datos proporcionan información relevante para la gestión de la EP y la utilización de recursos en España.

Since people with Parkinson's disease (PwP) can present several motor and non-motor symptoms (NMS), management of the disease is often complex, requiring a multidisciplinary approach that combines pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies.1–4 Treatment should be as individualized as possible, continuously adapting to the person's specific characteristics, mainly age and degree of disability, according to the disease stage, comorbidities, safety, tolerability, and cost of therapies.

Among the available pharmacotherapies, dopaminergic drugs such as levodopa, dopamine agonists (DA), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors are the most used for Parkinson's disease (PD), either in monotherapy (usually the first choice of treatment) or in combination.5 An increasing body of evidence also supports the inclusion of non-pharmacological approaches, such as physiotherapy, speech/language therapy, and occupational therapies, in the management of PD.1–4

PD impacts the quality of life (QoL) of both patients and caregivers. In addition to the physical and psychological impact upon PwP, PD leads to social changes in roles at home and work,6 affecting family and social relationships and causing deterioration of the caregiver's health.7,8 NMS, especially neuropsychiatric disturbances, particularly contribute to higher rates of caregiver burden.8

Due to the complexity of PD, real-world data studies have become a promising option for understanding everyday PD management and optimizing strategies and therapeutic options.9 In this context, the Parkinson's Real-World Impact Assessment (PRISM) study arose as a European survey to evaluate the burden of PD on patients and their caregivers.

The objective of the present work was to analyze the Spanish PRISM cohort and to describe prescribing patterns, healthcare and social care resource utilization, and the impact of PD on patients and their caregivers.

Material and methodsPRISM study designThe PRISM study was an international, cross-sectional, observational study conducted with 861 PwP and 256 caregivers from 6 European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom). Data were collected using an online questionnaire completed by PwP and their caregivers. The study design was published in detail.10

Study populationThis study analyzes data from the Spanish cohort dataset from the PRISM study.10 Patients were enrolled in the study by different patient advocacy groups and specialized PD clinics in Spain (Supplementary Table 1).

Questionnaires for PwPStructured questionnaires were used to assess the sociodemographic characteristics of PwP and information on PD diagnosis, comorbidities, pharmaceutical treatment, and healthcare resources. Patients were also asked if they had ever taken part in a clinical trial for a new treatment for PD. In addition, the burden of PD on family relationships and employment and retirement status was explored using a structured multiple-choice questionnaire.

The Spanish version of the 39-item Parkinson's Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (PDQ-39 SV)11 was used to assess the impact of PD on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) across 8 dimensions: mobility, activities of daily living (ADL), emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication, and bodily discomfort. Higher scores for each dimension and the PDQ-39 summary index (PDQ-39-SI) indicate poorer HRQoL.

Non-motor symptoms were evaluated using the validated 30-item self-completed Non-Motor Symptoms Questionnaire (NMSQuest; International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA).12 Symptoms are classed as mild for a total score of under 10 points, moderate for scores of 10–20 points, and severe for scores over 20 points.

A standardized questionnaire13,14 was used to assess impulse control behaviors (ICB). PwP were asked whether they, or people close to them, thought they had problems related to gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping, overeating, taking too much PD medication, or spending too much time on hobbies (“hobbyism”). Finally, the Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale (MOS-SFS)15 was included to evaluate impulsivity and sexual function.

Questionnaire for caregiversThe profile of PwP caregivers, including gender, age, relationship to the PwP, and the number of hours per week spent caring for the PwP, was obtained using structured questionnaires. Caregiver burden was measured using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI; Mapi Research Trust).16 Summarized scores range from 0 to 88 points, with higher scores indicating a greater burden.

Statistical methodsThe Stata statistics software (version 14) was used to perform the descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. Continuous variables were summarized using measures of centrality and dispersion, and categorical variables were summarized using frequency counts and percentages. When necessary, the variables were described in the 4 regions of the Spanish sample with the greatest representation (Andalusia, Catalonia, Galicia, and Madrid). The chi-square test was used to analyze the association or independence of categorical variables. A P-value<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

ResultsStudy populationThis subgroup analysis of the PRISM Spanish cohort dataset was conducted on 149 PwP at different stages and 38 primary caregivers from 13 regions of the Spanish territory (Supplementary Table 2).

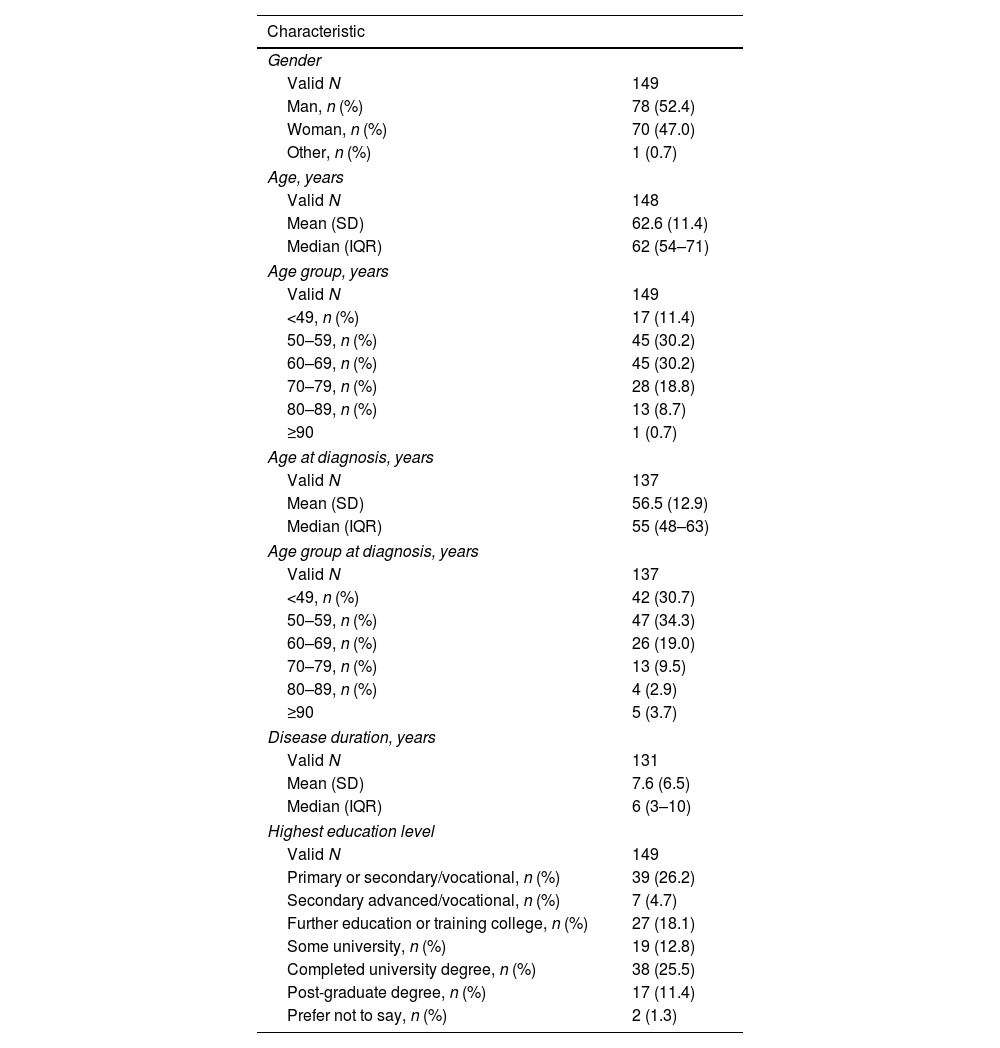

Characteristics of PwPTable 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the 149 PwP enrolled in the PRISM Spanish cohort. The mean age was 62.6 (SD [standard deviation]: 11.4) years, and 52.4% were male. The mean age at PD diagnosis was 56.5 (12.9) years, and the mean disease duration was 7.6 (6.5) years. Comorbidities were reported by 60.4% of PwP, with the most frequent (≥10% of participants) being hypertension (27.5%), depression (22.8%), anxiety (17.5%), rheumatological conditions (14.1%), and heart issues (10.1%) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Characteristics of patients in the PRISM cohort in Spain.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Valid N | 149 |

| Man, n (%) | 78 (52.4) |

| Woman, n (%) | 70 (47.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (0.7) |

| Age, years | |

| Valid N | 148 |

| Mean (SD) | 62.6 (11.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 62 (54–71) |

| Age group, years | |

| Valid N | 149 |

| <49, n (%) | 17 (11.4) |

| 50–59, n (%) | 45 (30.2) |

| 60–69, n (%) | 45 (30.2) |

| 70–79, n (%) | 28 (18.8) |

| 80–89, n (%) | 13 (8.7) |

| ≥90 | 1 (0.7) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |

| Valid N | 137 |

| Mean (SD) | 56.5 (12.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 55 (48–63) |

| Age group at diagnosis, years | |

| Valid N | 137 |

| <49, n (%) | 42 (30.7) |

| 50–59, n (%) | 47 (34.3) |

| 60–69, n (%) | 26 (19.0) |

| 70–79, n (%) | 13 (9.5) |

| 80–89, n (%) | 4 (2.9) |

| ≥90 | 5 (3.7) |

| Disease duration, years | |

| Valid N | 131 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.6 (6.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3–10) |

| Highest education level | |

| Valid N | 149 |

| Primary or secondary/vocational, n (%) | 39 (26.2) |

| Secondary advanced/vocational, n (%) | 7 (4.7) |

| Further education or training college, n (%) | 27 (18.1) |

| Some university, n (%) | 19 (12.8) |

| Completed university degree, n (%) | 38 (25.5) |

| Post-graduate degree, n (%) | 17 (11.4) |

| Prefer not to say, n (%) | 2 (1.3) |

IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; valid N: valid data from which the statistics were calculated for each variable (no missing data).

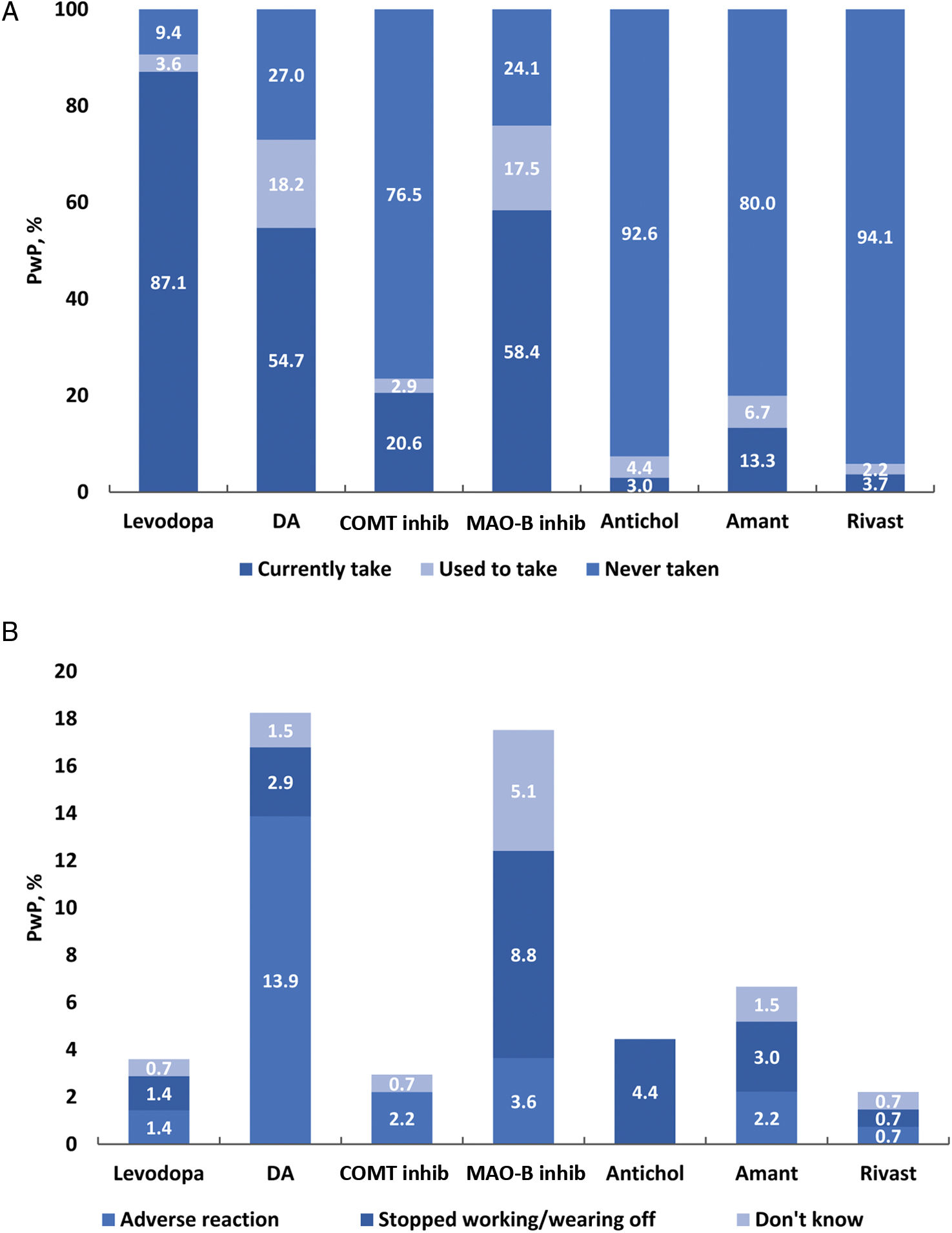

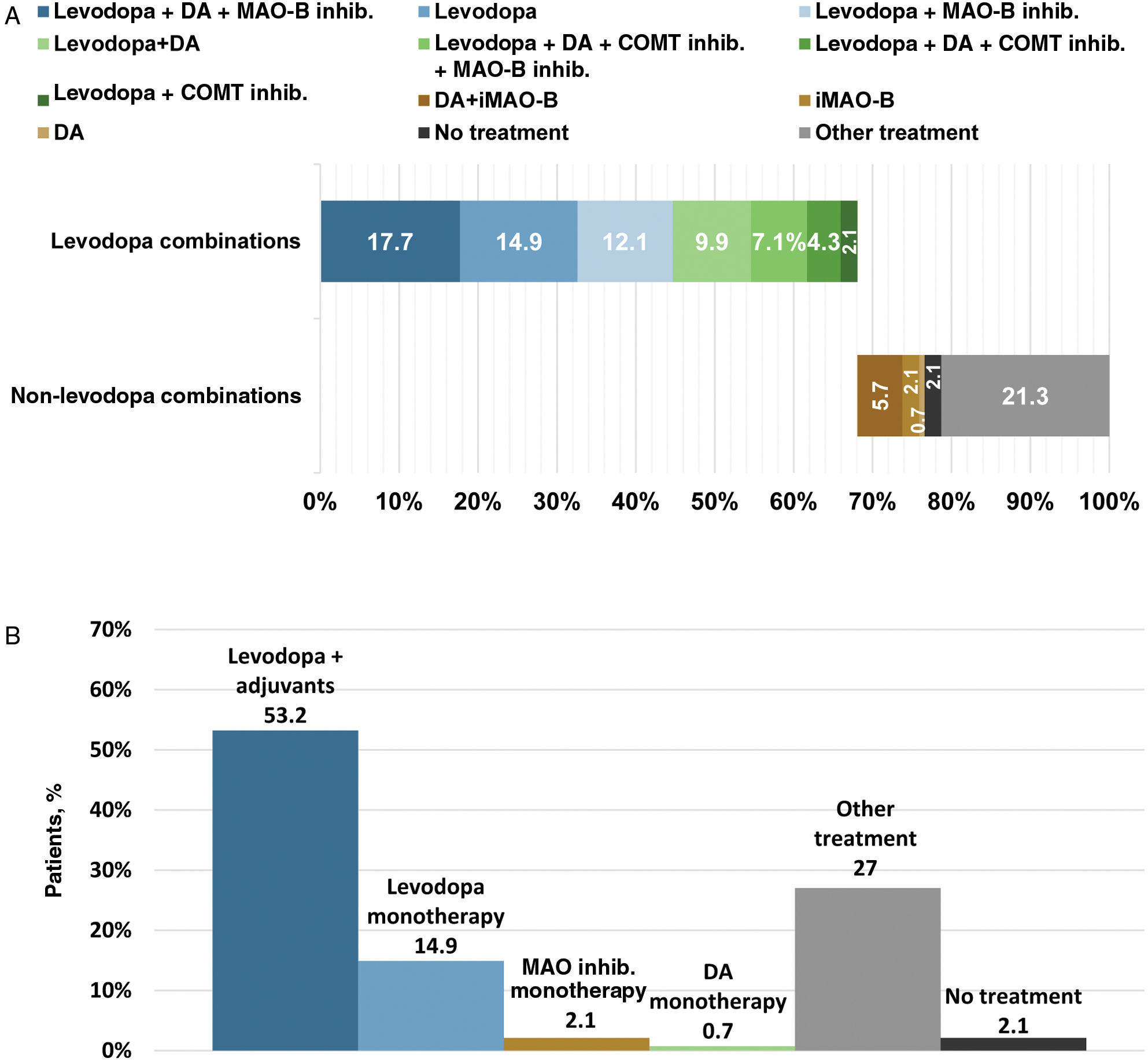

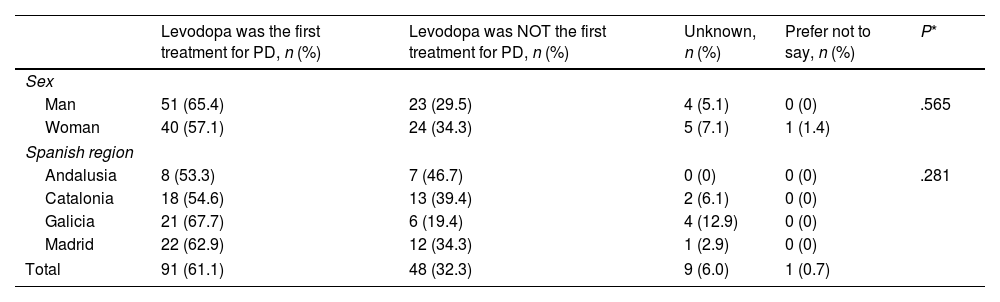

Levodopa was the first prescribed anti-PD medication for 61.1% of PwP. No statistical differences in the use of levodopa as first oral medication were observed between genders or Spanish regions (P>.05) (Table 2). Levodopa was prescribed within the first year after diagnosis in 59.7% of PwP and 1–2 years after diagnosis in 19.5% (Table 3). The use of levodopa increased with age, and most PwP (87.1%) had received levodopa in the 12 months before the survey. Additionally, MAO-B inhibitors, DA, and COMT inhibitors were taken in the previous 12 months by 58.4%, 54.7%, and 20.6% of patients, respectively (Fig. 1A). The main reasons for treatment discontinuation are detailed in Fig. 1B. In 53.2% of PwP, levodopa was prescribed with adjunctive therapies (DA±MAO inhibitors±COMT inhibitors), and 14.9% were receiving levodopa in monotherapy (Fig. 2).

Use of levodopa as first oral medication for Parkinson's disease by sex and region of the Spanish territory.

| Levodopa was the first treatment for PD, n (%) | Levodopa was NOT the first treatment for PD, n (%) | Unknown, n (%) | Prefer not to say, n (%) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Man | 51 (65.4) | 23 (29.5) | 4 (5.1) | 0 (0) | .565 |

| Woman | 40 (57.1) | 24 (34.3) | 5 (7.1) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Spanish region | |||||

| Andalusia | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .281 |

| Catalonia | 18 (54.6) | 13 (39.4) | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Galicia | 21 (67.7) | 6 (19.4) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Madrid | 22 (62.9) | 12 (34.3) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 91 (61.1) | 48 (32.3) | 9 (6.0) | 1 (0.7) | |

Time from diagnosis to the first levodopa prescription.

| Time from diagnosis to first levodopa prescription | n (%) |

|---|---|

| First year after diagnosis | 89 (59.7) |

| 1–2 years after diagnosis | 29 (19.5) |

| 3–4 years after diagnosis | 14 (9.4) |

| 5 or more years after diagnosis | 4 (2.7) |

| Never taken levodopa | 12 (8.1) |

| Preferred not to answer | 1(0.7) |

| Total | 149 (100) |

(A) Current (last 12 months) and previous use of anti-PD medications by therapeutic class. (B) Reasons for stopping the use of therapeutic classes. N excludes missing values, “prefer not to say” and “other”. Antichol, anticholinergics; Amant, amantadine; iCOMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor; DA, dopamine agonist; Levodopa, levodopa-containing therapy; iMAO-B, monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor; Rivast, rivastigmine; PwP, people with Parkinson's disease.

(A) Current (last 12 months) use of therapeutic combinations. (B) Current (last 12 months) use of levodopa combinations and anti-PD medication monotherapies. Therpeutic combinations shown include the 12 most common. iCOMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor; DA, dopamine agonist; iMAO-B, monoamine oxidase-b inhibitor; PwP, people with Parkinson's disease.

Five percent of patients were participating in a clinical trial for a new treatment for PD, 15% had previously participated in one, and 62.1% had never participated but would like to.

Healthcare and social care resource utilizationIn the past 12 months, most PwP had visited a specialist (e.g., neurologist, geriatrician) (96.9%) or general practitioner (GP) (91.3%). In addition, 57.7% had accessed physiotherapy services, 33% had attended speech-language therapy, and 25.8% had used mental health services. A total of 53.9% had required primary nursing care, and 21.7% reported receiving care from specialized nurses. None of the PwP accessed occupational therapy services. Data on medical visits are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

Almost 42% of PwP reported at least one emergency department visit, and 15.5% reported hospital admissions in the previous 12 months. Of those who had required an emergency department visit (n=17), falls were the most common reason (23.9%).

The use of additional resources, such as nursing services, a paid caregiver, overnight assistance, or daycare attendance, was infrequent, with most patients (71.8%) reporting usage of these resources less than once per month over the past 3 months.

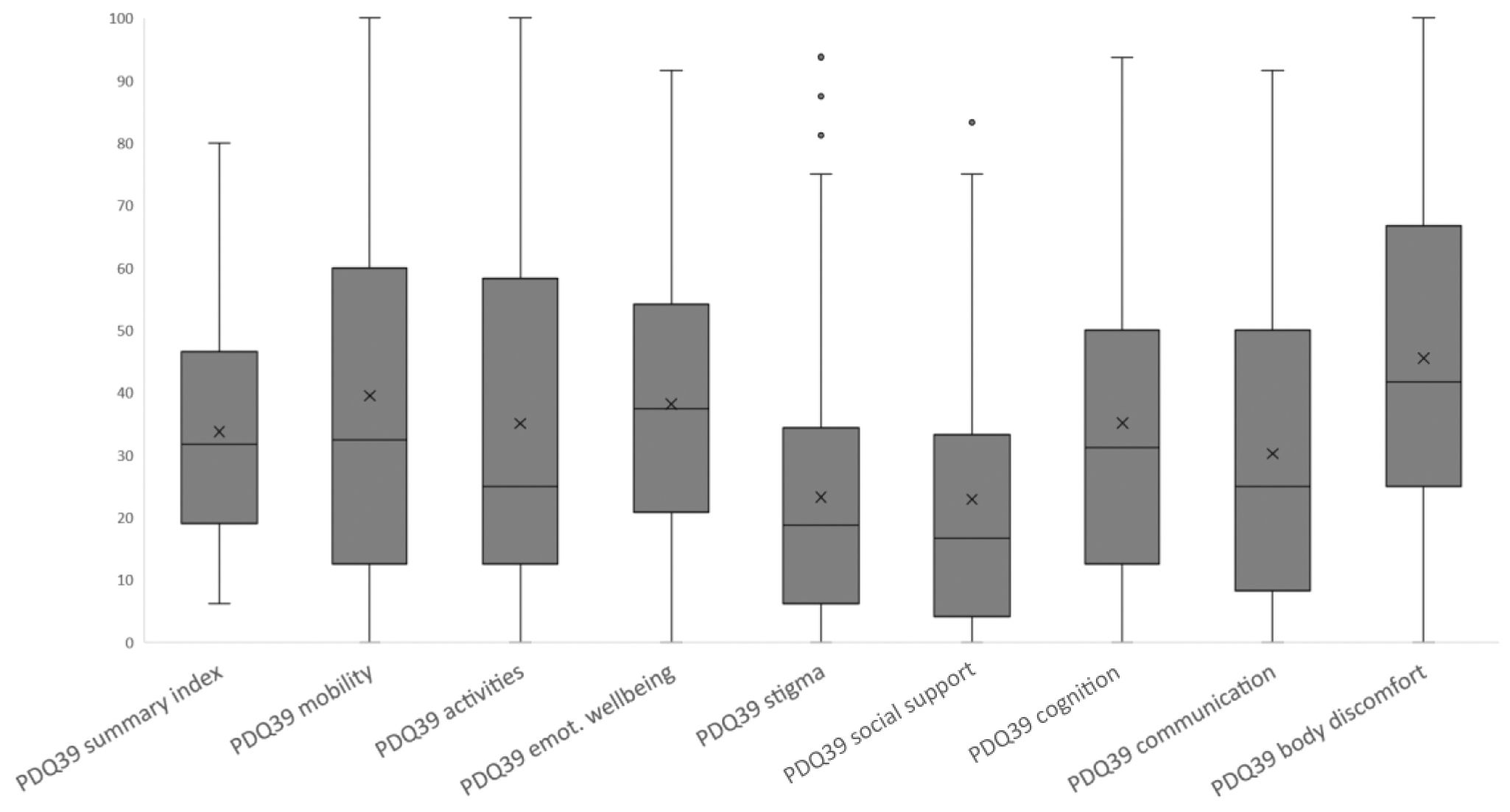

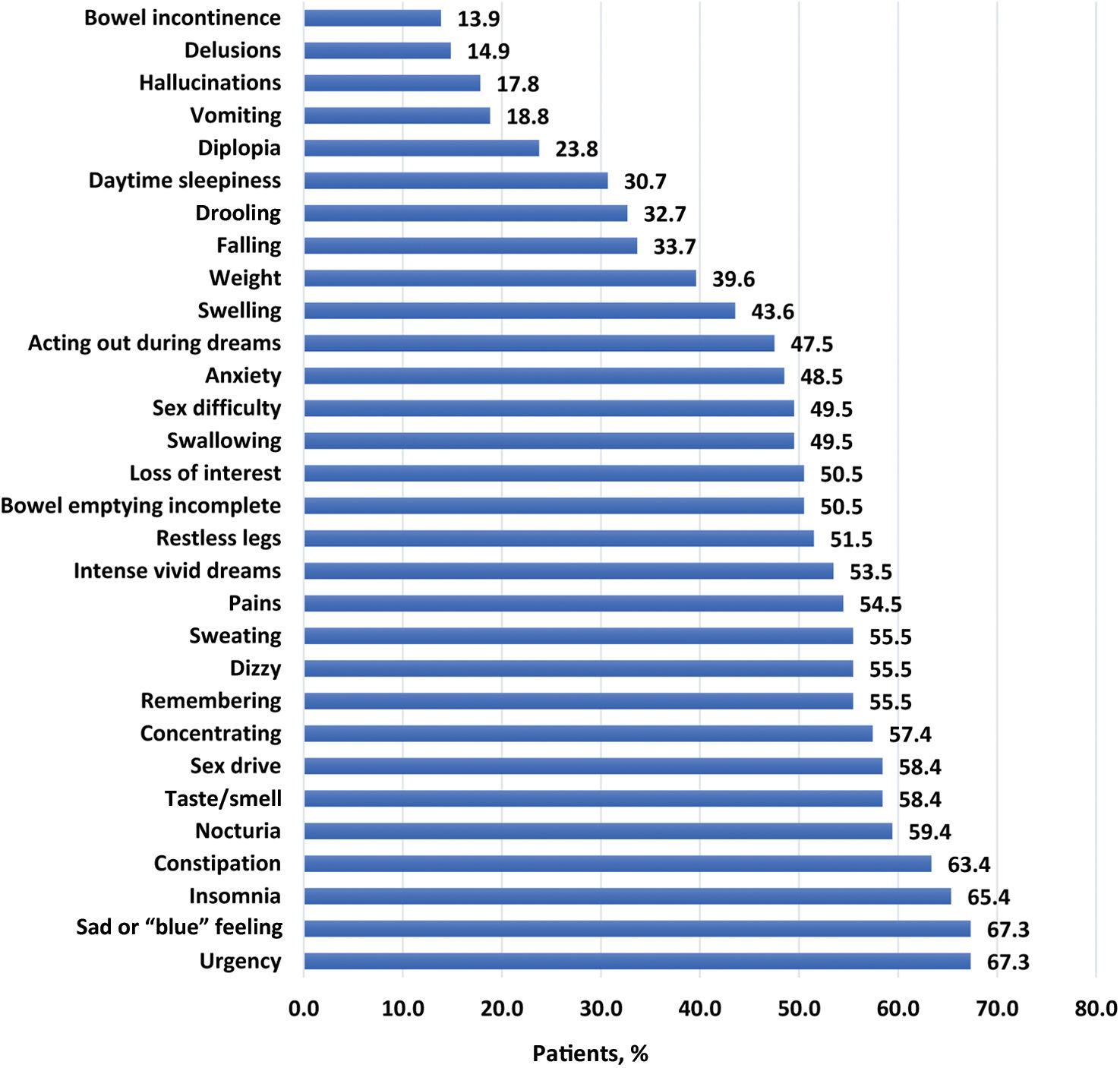

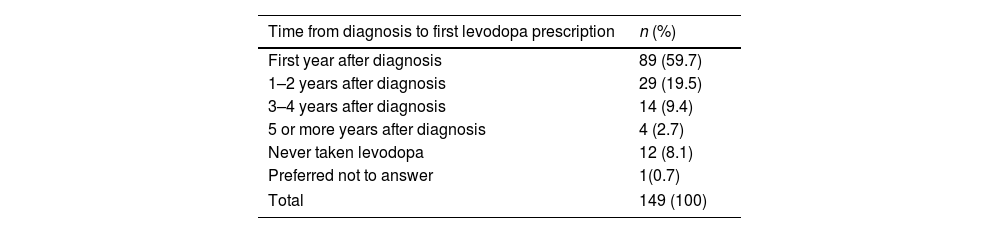

Impact of PD on HRQoL and control behaviorsThe median PDQ-39 summary score was 33.8 (interquartile range [IQR], 19.2–46.3), indicating that PwP had poor HRQoL (Fig. 3; Table 4). The highest domain scores (i.e., poorest HRQoL) were recorded for bodily discomfort (median, 45.5; IQR, 25.0–66.7), mobility (median, 39.6; IQR, 12.5–60.0), and emotional well-being (median, 38.2; IQR, 20.8–54.2). PwP also had a wide range of NMS, with a mean NMSQuest score of 13.9 (6.2) (Fig. 4; Table 4).

Health-related quality of life (measured using the PDQ-39), non-motor symptoms (measured using the NMSQuest), employment status, and retirement status in patients with Parkinson's disease.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| PDQ-39 summary score | |

| Valid N | 149 |

| Median (IQR) | 31.8 (19.2–46.3) |

| NMSQuest score | |

| Valid N | 101 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (6.2) |

| Current employment status | |

| Valid N | 104 |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 74 (71.2) |

| In paid employment, n (%) | 19 (18.3) |

| Other (e.g., on sick leave), n (%) | 11 (10.6) |

| Reduction in the number of hours of work (per week) over the past 12 months, in those who reported being in paid employment | |

| Valid N | 15 |

| <5h, n (%) | 1 (6.7) |

| 5–10h, n (%) | 2 (13.3) |

| 11–15h, n (%) | 1 (6.7) |

| 16–20h, n (%) | 1 (6.7) |

| >20h, n (%) | 3 (20.0) |

| 0 (no reduction), n (%) | 2 (13.3) |

| Prefer not to say, n (%) | 5 (33.3) |

| Early retirement | |

| Valid N | 65 |

| Retired early, not due to PD, n (%) | 29 (44.6) |

| Retired early, but PD was not the main reason, n (%) | 5 (7.7) |

| Retired early, PD was the main reason, n (%) | 30 (46.2) |

| Prefer not to say, n (%) | 1 (1.5) |

| Reduction in hours of daily activities (per week) over the past 12 months | |

| Valid N | 102 |

| 0 (no reduction), n (%) | 37 (36.3) |

| <5h, n (%) | 13 (12.8) |

| 5–10h, n (%) | 14 (13.7) |

| 11–15h, n (%) | 7 (6.9) |

| 16–20h, n (%) | 6 (5.9) |

| >20h, n (%) | 15 (14.7) |

| Prefer not to say, n (%) | 10 (9.8) |

IQR: interquartile range; NMSQuest: Non-Motor Symptoms Questionnaire; PD: Parkinson's disease; PDQ-39: Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39; SD: standard deviation; valid N: valid data from which the statistics have been calculated in each variable (no missing data).

A majority (71.2%) of PwP were not working at the time of the survey. Among those still working, 31.6% reported having reduced work hours in the last 12 months due to PD (Table 4). In addition, 53.9% of PwP reported having reduced the time spent on daily activities in the previous 12 months (Table 4), and approximately 75% reported that PD had adversely affected family relationships moderately (29.4%) or very much (44.1%) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Approximately 57% of PwP had at least one ICB; 60% of men experienced difficulties with achieving or maintaining an erection, and 60% of women had problems with orgasm.

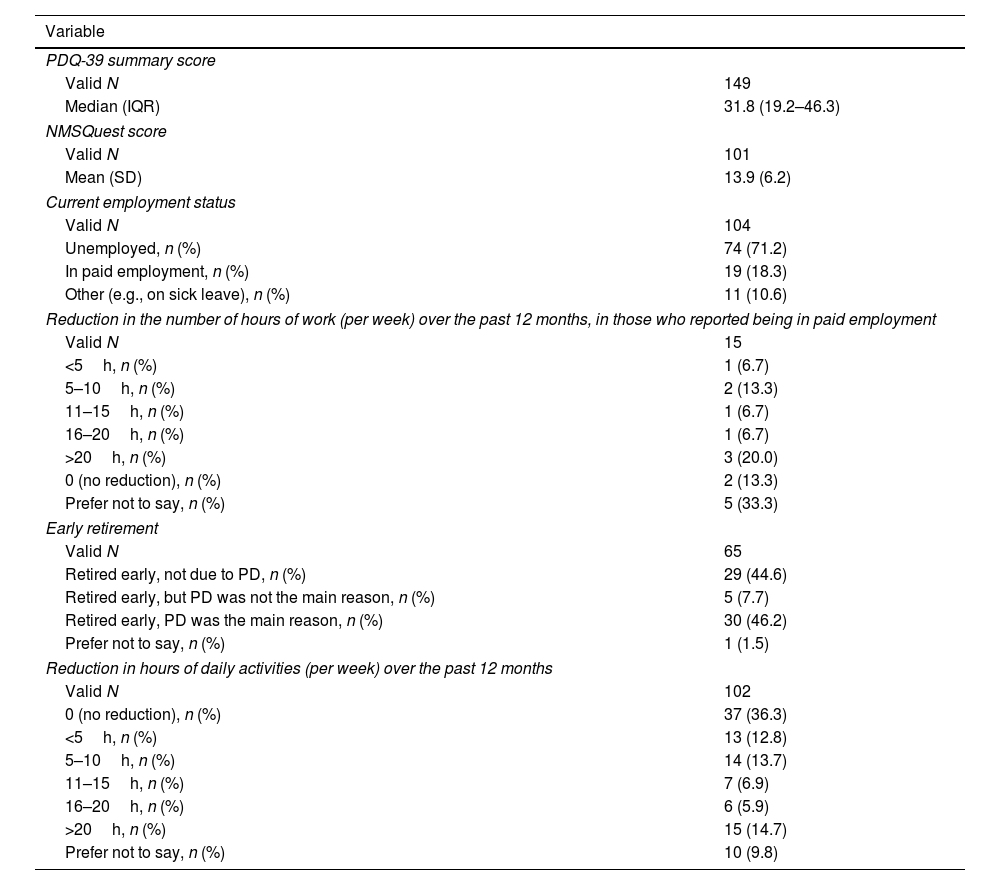

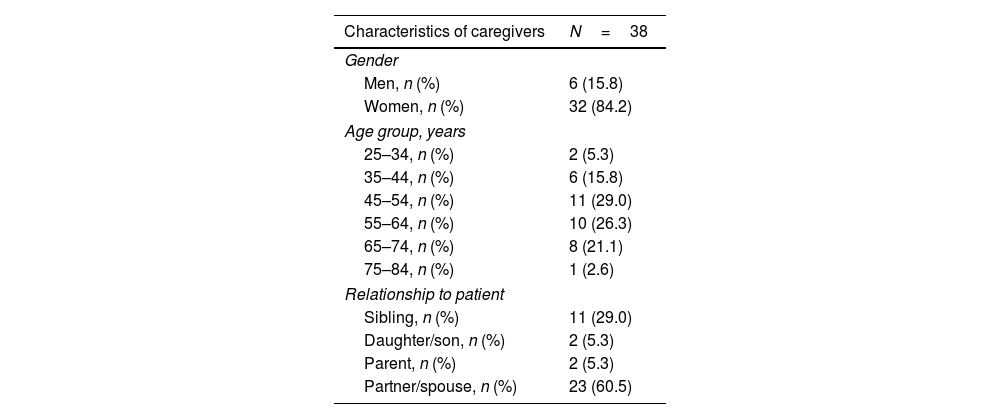

Impact of caring for caregiversSocio-demographic data, including information on the caregiver's relationship with the PwP, are shown in Table 5. Most caregivers (55.3%) were aged between 45 and 64 years old, were women (84.2%), and were the partner/spouse of the PwP (60.5%).

Characteristics of caregivers of patients with Parkinson's disease.

| Characteristics of caregivers | N=38 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men, n (%) | 6 (15.8) |

| Women, n (%) | 32 (84.2) |

| Age group, years | |

| 25–34, n (%) | 2 (5.3) |

| 35–44, n (%) | 6 (15.8) |

| 45–54, n (%) | 11 (29.0) |

| 55–64, n (%) | 10 (26.3) |

| 65–74, n (%) | 8 (21.1) |

| 75–84, n (%) | 1 (2.6) |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Sibling, n (%) | 11 (29.0) |

| Daughter/son, n (%) | 2 (5.3) |

| Parent, n (%) | 2 (5.3) |

| Partner/spouse, n (%) | 23 (60.5) |

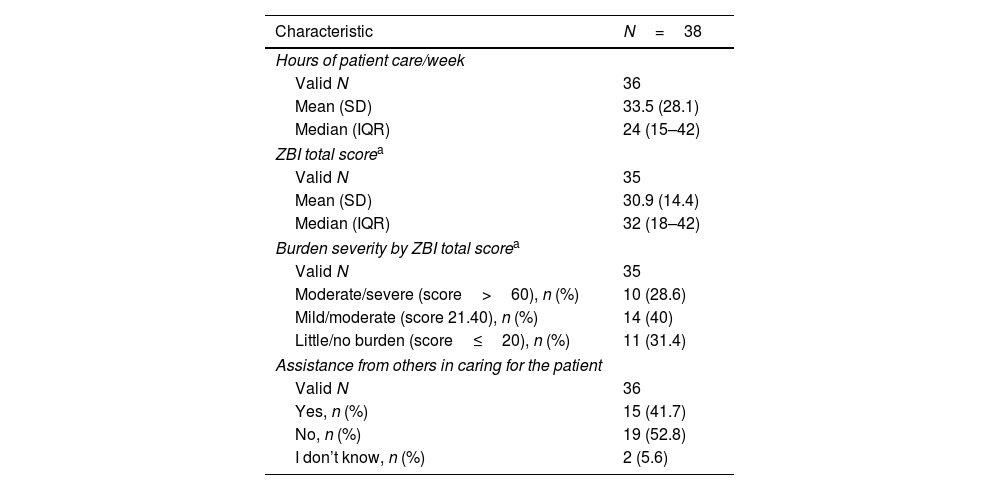

Caregivers reported spending a mean of 33.5h/week caring for the PwP, and a majority (52.8%) did not have social network (family/friends/acquaintances) support to assist with caregiving. Overall, caregivers reported mild to moderate burden (mean ZBI total score, 30.9 [14.4]) (Table 6).

Burden of caregivers of patients with Parkinson's disease.

| Characteristic | N=38 |

|---|---|

| Hours of patient care/week | |

| Valid N | 36 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.5 (28.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 24 (15–42) |

| ZBI total scorea | |

| Valid N | 35 |

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (14.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 32 (18–42) |

| Burden severity by ZBI total scorea | |

| Valid N | 35 |

| Moderate/severe (score>60), n (%) | 10 (28.6) |

| Mild/moderate (score 21.40), n (%) | 14 (40) |

| Little/no burden (score≤20), n (%) | 11 (31.4) |

| Assistance from others in caring for the patient | |

| Valid N | 36 |

| Yes, n (%) | 15 (41.7) |

| No, n (%) | 19 (52.8) |

| I don’t know, n (%) | 2 (5.6) |

Approximately 55% of caregivers reported that PD impacted their family relationships moderately (32.4%) or very much (23.5%). In addition, about 55% reported that this impact had increased moderately (21.9%), very much (25%), or extremely (6.3%) as PD had progressed (Supplementary Fig. 2).

DiscussionThis study provides important information regarding the prescribing patterns, use of healthcare and social resources, and the burden of PD on both patients and caregivers in Spain.

Similarly to the results of the European PRISM study, levodopa was the first prescribed PD medication in a large number of PwP in Spain (61.1%).10 It was generally prescribed within the first year after diagnosis, regardless of the Spanish region. This result is consistent with recent studies demonstrating that withholding levodopa in favor of other treatments is not useful.17–19 Monotherapy with DAs was almost non-existent in the Spanish PRISM cohort, suggesting that the prescribing practice is evolving toward widespread use of levodopa as the initial symptomatic treatment in Spain.

The high percentage of patients (62.1%) who expressed interest in participating in a clinical trial highlights the willingness of Spanish PwP to engage in research and potentially access new treatment options. This percentage stands in contrast with the low numbers of PwP in our cohort that reported a current or previous enrollment in a clinical trial, indicating the existence of barriers that prevent some patients from participating in these studies. Such barriers may include a lack of awareness of available trials, difficulty meeting eligibility criteria, and logistical challenges, such as distance from trial sites.20 In other countries, approaches such as registries of patients interested in participating in clinical trials21 and online tools connecting participants to trials (such as the Fox Trial Finder22) have been successful in increasing awareness and accessibility.

A multidisciplinary approach is generally recommended for the management of PD.1,23–26 Our results suggest that PwP in Spain have low use rates for non-pharmacological interventions, with physiotherapy being the most used. The rates of use are lower than those observed in other European cohorts.10,27 A 2016 report28 showed that only a few movement disorders units in Spain are organized to provide multidisciplinary care. In contrast, the use of primary nursing care was much more common in the PRISM Spanish cohort (53.9% vs 28.2% in Europe), which may indicate the increasing relevance of nursing in the education, support, and follow-up of PD patients.29

Nearly half of the PwP in our study reported at least one emergency department visit in the last year, which was considerably higher than the rate reported in the European results (42% vs 26%). As in other published studies, falls were the most frequent reason.23,30 This higher emergency department attendance rate in Spain may result from inappropriate use of emergency department services, estimated between 24% and 79%.31 Falls are an independent predictor factor, associated with a threefold increase in the risk of acute hospitalization,30 which is in turn associated with increased morbidity and mortality.32

The total PDQ-39 score in PwP in Spain was worse than that observed in the European PRISM cohort (33.8 vs 29.1).10 There were no differences in demographic characteristics or known predictors of HRQoL (stage of disease progression, NMS burden, or presence of other comorbidities).33–35 Differences in access to healthcare and social care resources could potentially contribute to the differences in HRQoL.

In the Spanish PRISM cohort, 57% of PwP had at least one ICB, a higher prevalence rate than those reported in other previous studies.36,37 Using a standardized questionnaire rather than a validated scale may have favored these results. In this sense, Scott et al.38 found a significantly higher prevalence of any impulse control disorder based on online (56.7%) vs in-person (33.3%) administration of the Questionnaire for Impulsive–Compulsive Disorders Rating Scale. These results suggest that ICB symptoms may be underreported in consultations.38

Overall, the disease burden reported by caregivers was higher in the Spanish dataset than in the European cohort (mean ZBI total score: 30.9 vs 26.6), coinciding with a higher mean time per week spent in caring for the PwP (33.5 vs 22.5h/week). Studies on the characteristics of informal caregivers in PD and other long-term diseases confirm the high percentage of women involved in patient care in Spain.39,40 However, the gender of the caregiver seems to have little or no effect on caregiver burden in PD.39,41,42

Since this was an observational study, prescribing patterns and healthcare and social care resource utilization outcomes may be considered close to real-world clinical practice. Still, conclusions may have limitations. The results reported may not be representative of the entire country. They may differ considerably across different regions in Spain, but the sample size was insufficient to study differences in healthcare resources and treatment patterns between regions. In addition, the Spanish PRISM sample may not have been fully representative of the PD population in Spain because: (1) PwP were invited to participate voluntarily through patient advocacy groups and specialized PD clinics in Spain; (2) the survey was conducted online, so people with difficulty accessing the Internet (for economic or educational reasons, or because of an advanced disease stage) and very elderly people were 2 groups that are potentially underrepresented (only 9.4% of the PwP were aged ≥80 years); and, in this regard, (3) the mean age in the PwP (62.6 years old) is lower than the expected mean age of PwP in Spain, with disease incidence peaking between 75 and 85 years of age.28 Data regarding motor disability are not available in PRISM, which represents another limitation of the study.

Although the Spanish PRISM cohort was similar to the European cohort in terms of demographic (age, sex) and clinical characteristics of the PwP, significant differences were observed in the use of medical resources and the amount of time dedicated to patient care. On the one hand, the study highlights the limitations of using rehabilitation therapies and the higher rates of emergency department visits. On the other, it provides information regarding the impact of the disease on PwP and their caregivers, even at a relatively young age and at a mild/moderate stage of the disease. More research is needed to promote interventions to facilitate access to social and healthcare resources.

FundingThe study, data analysis, and manuscript preparation were funded by Bial – Portela & Ca, S.A..

Conflict of interestCPM has no conflict of interest to report.

IP is an employee of Bial – Portela & Ca, S.A.

ABR has no conflict of interest to report.

JCMC has received grants/research support from Allergan, AbbVie, Bial, Ipsen, Italfarmaco, Merz, and Zambon; honoraria or consultation fees from Allergan, AbbVie, Bial, Exeltis, Ipsen, Italfarmaco, Merz, Ipsen, Orion, TEVA, UCB, and Zambon; and company-sponsored speakers bureau fees from Allergan, AbbVie, Bial, Krka, Ipsen, Italfarmaco, Merz, TEVA, UCB, and Zambon.

ASI has no conflict of interest to report.

ETS has no conflict of interest to report.

Data availabilityBIAL is committed to helping improve the care of PD patients through high-quality scientific research. The full results dataset will be made available for further analysis to any healthcare professional or academic researcher at https://prism.bial.com/.

The authors deeply thank all the patients and carers who kindly provided their time to answer the survey, as well as the Patients’ Association Groups who helped in its distribution. Editorial assistance was provided by Outcomes10 and funded by Bial – Portela & Ca, S.A.