Seizure clusters (SC) constitute a prevalent condition with high risk of progression to status epilepticus, whose management requires a methodical approach. This study aimed to determine the clinical and sociodemographic profile, course, and outcomes of patients with SC.

MethodsAn analysis was conducted of the subgroup of patients with SC and isolated epileptic seizures (IES) included in the institutional “seizure code” protocol. Baseline characteristics were described and analyses were conducted to identify potential predictors of the condition and compare hospital outcomes between groups.

ResultsA total of 485 patients were included in the “seizure code” protocol from 23 March to 20 August 2023, of whom 21.2% (n=103) presented SC and 60.8% (n=295) IES. A total of 75.7% of patients with SC had history of epilepsy. Younger patients (P=.028), patients with history of epilepsy (P=.0014), and those taking ≥3 antiseizure medications (P=.046) have an increased risk of presenting SC. Poor treatment adherence was the most common etiology. Patients with SC had longer hospital stays than those with IES (37.9 vs 26.8h; P=.005). However, we did not find statistically significant differences in the prevalence of complications, admissions to the intensive care unit, or in-hospital seizure recurrence.

ConclusionsSC are common in emergency departments, with a prevalence of 21.2% in this study. They most frequently affect younger patients, individuals with history of epilepsy, and those receiving ≥3 antiseizure medications. In this context, the main etiology was poor treatment adherence.

Las crisis en salvas (CS) son una condición prevalente, con alto riesgo de progresar a estado epiléptico, lo que requiere un enfoque metódico. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar el perfil clínico y sociodemográfico, el curso y los desenlaces de los pacientes con CS.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis del subgrupo de pacientes con CS y crisis epilépticas aisladas (CEA) incluidos en el protocolo institucional de «código crisis». Se describieron las características basales, se realizó un análisis para identificar posibles predictores de la condición y comparar los resultados hospitalarios entre los grupos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 485 pacientes en el protocolo de código crisis entre el 23 de marzo y el 20 de agosto de 2023, de los cuales el 21,2% (n=103) presentó CS y el 60,8% (n=295) CEA. El 75,7% de los pacientes con CS tenían antecedente de epilepsia. Los pacientes más jóvenes (p=0,028), con antecedente de epilepsia (p=0,0014) y que tomaban ≥3 medicamentos anticrisis (MAC) (p=0,046), tuvieron un mayor riesgo de presentarse con CS. La mala adherencia a la medicación fue la etiología más común. Los pacientes con CS tuvieron una estancia hospitalaria más larga que aquellos con CEA (37,9 vs. 26,8h; p=0,005). Sin embargo, no hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la prevalencia de complicaciones, necesidad de ingreso a la unidad de cuidados intensivos o recurrencia de crisis.

ConclusionesLas CS son frecuentes, con una prevalencia del 21,2% en este estudio. Es más frecuente en los pacientes más jóvenes, con antecedente de epilepsia y uso de ≥3 MAC. En este contexto, la principal etiología fue la mala adherencia a la medicación.

Status epilepticus and acute repetitive seizures, also known as seizure clusters (SC), are very frequent neurological emergencies with a high medical impact.1,2 Although there is no universal definition for SC, the most widely accepted is the occurrence of ≥3 epileptic seizures within 24h or, in patients with epilepsy, an increase in the number, severity, and duration of epileptic seizures compared to baseline.3 This prevalent and understudied condition presents a high risk of progression to status epilepticus, requiring rapid, methodical management to prevent the associated complications.3–5 These two conditions are thought to share a very similar pathophysiology, involving failure of the brain's intrinsic mechanisms to abort an epileptic seizure. Furthermore, patients presenting SC have poorer quality of life; higher likelihood of visiting the emergency department (which results in an increase in direct and indirect healthcare costs); and greater risk of psychotic episodes, recurrent SC, and status epilepticus.3,6,7 Moreover, some studies have shown that patients with SC present greater lifetime risk of death than those without SC. Considering all these factors, management of SC has become a priority in recent years. It relies upon the use of rescue medications in the pre-hospital setting, typically non-intravenous benzodiazepines. This approach has been proven to be effective, decreasing the risk of progression to status epilepticus.8–10 Unfortunately, these medications are not widely available in most low- and middle-income countries. Despite the effectiveness of fast-acting intravenous benzodiazepines, such as diazepam or midazolam, concerns remain about this drug class, mainly due to the risk of ventilatory failure, especially in elderly patients.11,12 In this context, intravenous antiseizure medications (ASM) have emerged as an effective alternative in the hospital setting.13,14

In the light of the above, the purpose of this study was to compare the clinical and sociodemographic profiles, as well as hospital outcomes, of patients with SC and those with isolated seizures.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study, nested within a prospective cohort study. This study evaluated the subgroup of patients with SC and isolated epileptic seizures included in the cohort study in which we proved the efficacy of the “seizure code” protocol. Following this protocol, the prospective cohort study included patients over 18 years of age who were admitted to the emergency department of Hospital Occidente de Kennedy between 23 March and 20 August 2023 due to severe epileptic seizures. The clinical scenario was classified by the seizure code team into isolated epileptic seizures, SC, or status epilepticus. Patients classified into the first two categories were included in this study. The following demographic and clinical data were collected: age, sex, history of epilepsy, type of epilepsy, previous ASMs and ASMs that patients were receiving at the time of admission, pre-hospital treatment administration, type of clinical scenario, type of medication and dosage (per kg body weight) where applicable, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, duration of hospital stay, seizure recurrence during hospitalization, and death during hospitalization. The number of ASMs in patients with history of epilepsy was dichotomized as 0–2 or ≥3. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, with approval number 6 of 2024. The definitions used in this study are as follows:

- •

Isolated epileptic seizure was defined as any seizure attended at the emergency department. According to the ILAE definition, a seizure was defined as the transient occurrence of signs and symptoms caused by abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity.

- •

Seizure cluster was defined as the occurrence of three or more seizures within a 24-h period in patients with no history of epilepsy, or the occurrence of three or more seizures that represents a significant increase in baseline seizure frequency in patients with history of epilepsy.3 According to our management protocol, all patients with SC were treated exclusively with intravenous ASM.

The statistical analysis was conducted using the STATA software, version 17. The results of the descriptive analysis are presented using frequency tables and graphs, for qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion, for continuous variables. Normality of the continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The association between independent and dependent variables was assessed using the chi-square test, for dichotomous categorical variables, and the unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test, depending on the normality of the variable. Statistical significance was established at P<.05.

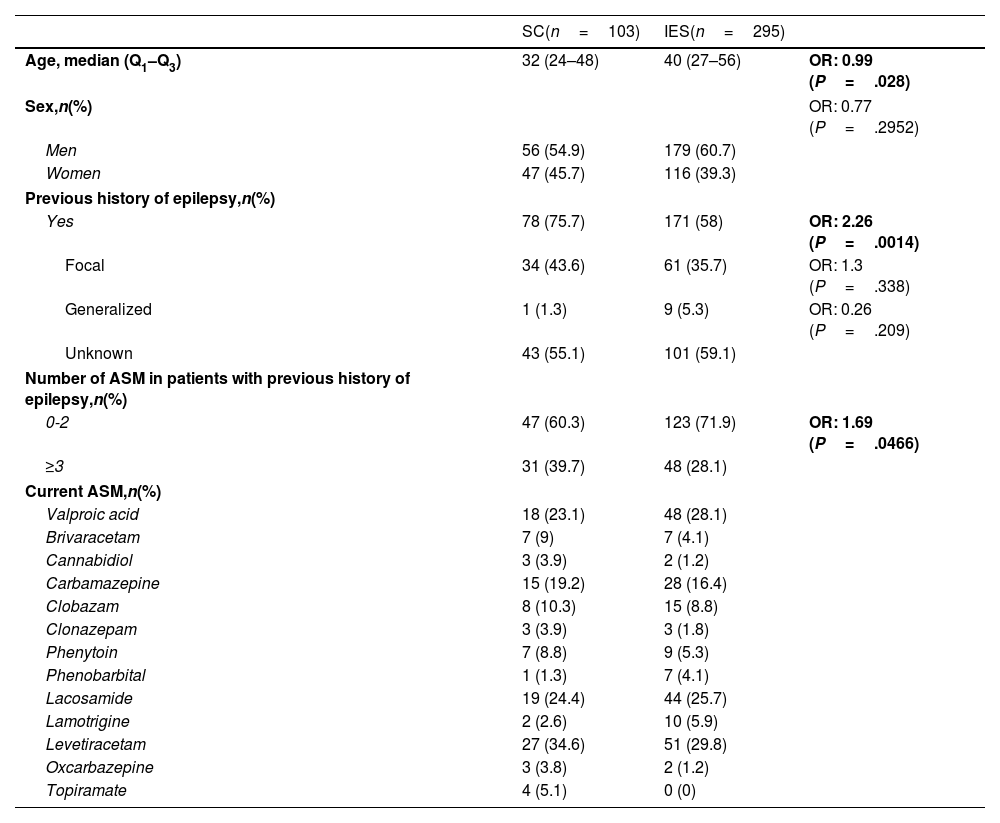

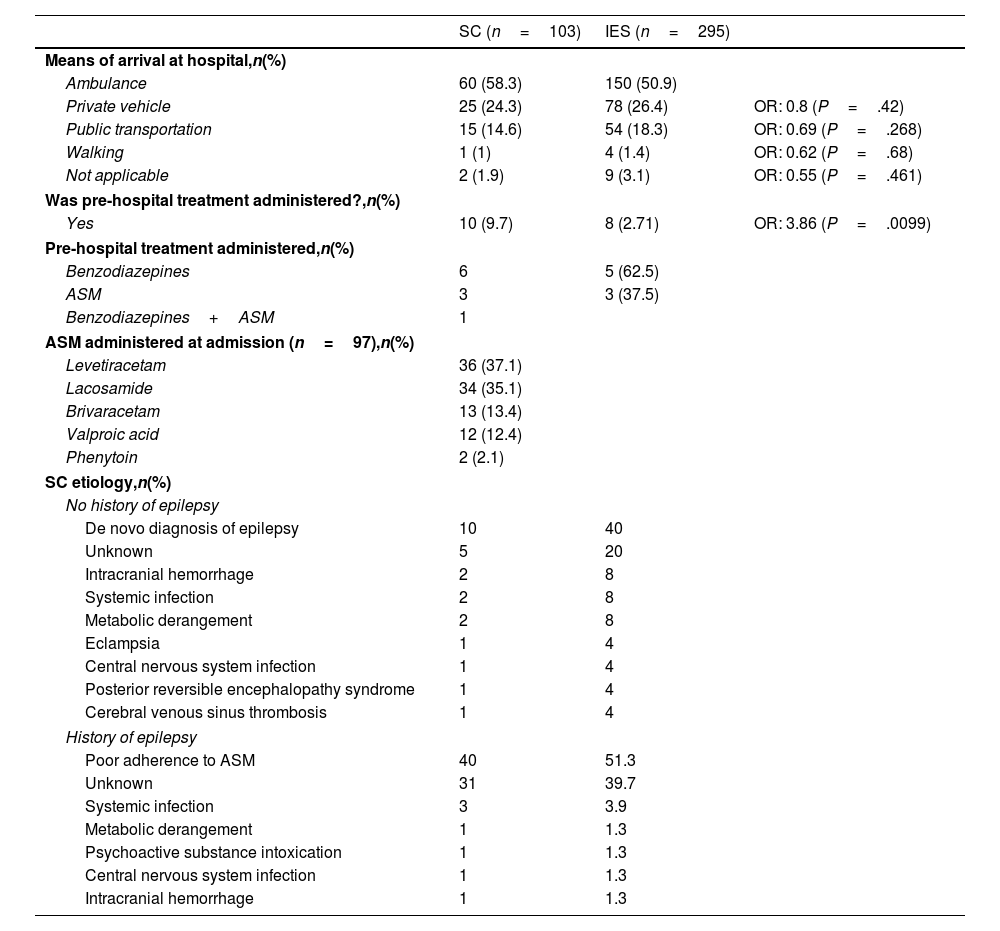

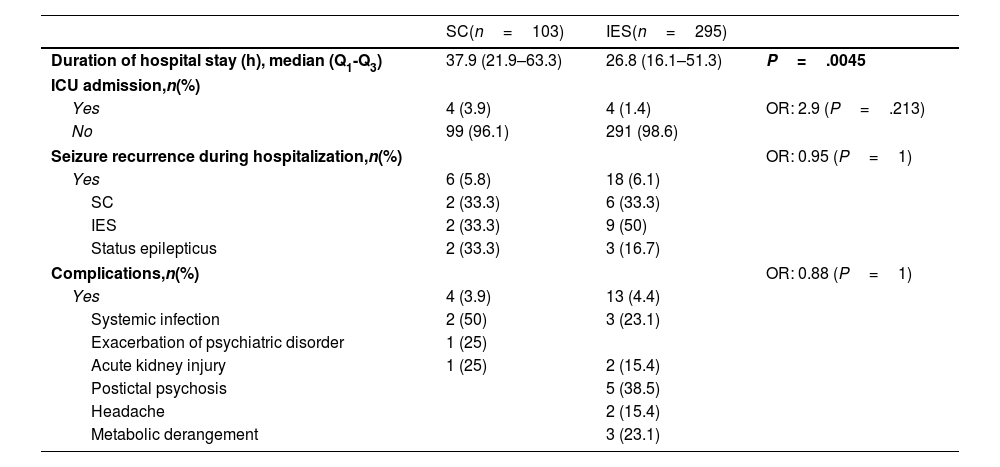

ResultsA total of 485 patients were included in the seizure code protocol between 23 March and 20 August 2023; 21.2% of these (n=103) were admitted due to SC and 60.8% (n=295) due to isolated seizures. Patients with SC had a median age of 32 years (Q1–Q3: 24–48). In this group, 75.7% of patients had history of epilepsy, and 39.7% were receiving more than three ASM. Compared to patients with isolated seizures, patients with SC were younger (P=.028), and more frequently had history of epilepsy (P=.001) and polytherapy (P=.047). Baseline clinical and sociodemographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Regarding type of epilepsy, we found no statistically significant differences between groups. The most frequent classification of epilepsy type was unknown, followed by focal and generalized epilepsy. A low percentage of patients with SC received some type of medication in the pre-hospital setting (9.7%), despite the fact that 58.3% arrived at hospital by ambulance. In spite of this low rate of pre-hospital treatment, patients with SC were more likely to receive any type of treatment than patients with isolated seizures (OR, 3.86; P=.01); upon hospital arrival, all of them were treated with intravenous ASM according to our protocol (Table 2). Regarding the etiology of SC, among patients with history of epilepsy, the most frequent cause was poor adherence to ASM (51.3%), followed by unknown etiology (39.7%); among patients without history of epilepsy, most cases were de novo (40%), followed by intracerebral hemorrhage (8%) and systemic infection (8%) (Table 2). Regarding hospital outcomes, the duration of hospital stay (in hours) was longer in patients with SC (median: 37.9) than in those with isolated seizures (median: 26.8; P=.005). However, we found no statistically significant differences in terms of ICU admission, in-hospital seizure recurrence, or medical complications (Table 3).

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics.

| SC(n=103) | IES(n=295) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1–Q3) | 32 (24–48) | 40 (27–56) | OR: 0.99 (P=.028) |

| Sex,n(%) | OR: 0.77 (P=.2952) | ||

| Men | 56 (54.9) | 179 (60.7) | |

| Women | 47 (45.7) | 116 (39.3) | |

| Previous history of epilepsy,n(%) | |||

| Yes | 78 (75.7) | 171 (58) | OR: 2.26 (P=.0014) |

| Focal | 34 (43.6) | 61 (35.7) | OR: 1.3 (P=.338) |

| Generalized | 1 (1.3) | 9 (5.3) | OR: 0.26 (P=.209) |

| Unknown | 43 (55.1) | 101 (59.1) | |

| Number of ASM in patients with previous history of epilepsy,n(%) | |||

| 0-2 | 47 (60.3) | 123 (71.9) | OR: 1.69 (P=.0466) |

| ≥3 | 31 (39.7) | 48 (28.1) | |

| Current ASM,n(%) | |||

| Valproic acid | 18 (23.1) | 48 (28.1) | |

| Brivaracetam | 7 (9) | 7 (4.1) | |

| Cannabidiol | 3 (3.9) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Carbamazepine | 15 (19.2) | 28 (16.4) | |

| Clobazam | 8 (10.3) | 15 (8.8) | |

| Clonazepam | 3 (3.9) | 3 (1.8) | |

| Phenytoin | 7 (8.8) | 9 (5.3) | |

| Phenobarbital | 1 (1.3) | 7 (4.1) | |

| Lacosamide | 19 (24.4) | 44 (25.7) | |

| Lamotrigine | 2 (2.6) | 10 (5.9) | |

| Levetiracetam | 27 (34.6) | 51 (29.8) | |

| Oxcarbazepine | 3 (3.8) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Topiramate | 4 (5.1) | 0 (0) | |

ASM: antiseizure medications; IES: isolated epileptic seizures; OR: odds ratio; SC: seizure clusters.

Values shown in bold are statistically significant.

Clinical scenario at admission.

| SC (n=103) | IES (n=295) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Means of arrival at hospital,n(%) | |||

| Ambulance | 60 (58.3) | 150 (50.9) | |

| Private vehicle | 25 (24.3) | 78 (26.4) | OR: 0.8 (P=.42) |

| Public transportation | 15 (14.6) | 54 (18.3) | OR: 0.69 (P=.268) |

| Walking | 1 (1) | 4 (1.4) | OR: 0.62 (P=.68) |

| Not applicable | 2 (1.9) | 9 (3.1) | OR: 0.55 (P=.461) |

| Was pre-hospital treatment administered?,n(%) | |||

| Yes | 10 (9.7) | 8 (2.71) | OR: 3.86 (P=.0099) |

| Pre-hospital treatment administered,n(%) | |||

| Benzodiazepines | 6 | 5 (62.5) | |

| ASM | 3 | 3 (37.5) | |

| Benzodiazepines+ASM | 1 | ||

| ASM administered at admission (n=97),n(%) | |||

| Levetiracetam | 36 (37.1) | ||

| Lacosamide | 34 (35.1) | ||

| Brivaracetam | 13 (13.4) | ||

| Valproic acid | 12 (12.4) | ||

| Phenytoin | 2 (2.1) | ||

| SC etiology,n(%) | |||

| No history of epilepsy | |||

| De novo diagnosis of epilepsy | 10 | 40 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 20 | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 2 | 8 | |

| Systemic infection | 2 | 8 | |

| Metabolic derangement | 2 | 8 | |

| Eclampsia | 1 | 4 | |

| Central nervous system infection | 1 | 4 | |

| Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome | 1 | 4 | |

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis | 1 | 4 | |

| History of epilepsy | |||

| Poor adherence to ASM | 40 | 51.3 | |

| Unknown | 31 | 39.7 | |

| Systemic infection | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Metabolic derangement | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Psychoactive substance intoxication | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Central nervous system infection | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 1 | 1.3 | |

ASM: antiseizure medications; IES: isolated epileptic seizures; OR: odds ratio; SC: seizure clusters.

Hospitalization outcomes.

| SC(n=103) | IES(n=295) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of hospital stay (h), median (Q1-Q3) | 37.9 (21.9–63.3) | 26.8 (16.1–51.3) | P=.0045 |

| ICU admission,n(%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (3.9) | 4 (1.4) | OR: 2.9 (P=.213) |

| No | 99 (96.1) | 291 (98.6) | |

| Seizure recurrence during hospitalization,n(%) | OR: 0.95 (P=1) | ||

| Yes | 6 (5.8) | 18 (6.1) | |

| SC | 2 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | |

| IES | 2 (33.3) | 9 (50) | |

| Status epilepticus | 2 (33.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Complications,n(%) | OR: 0.88 (P=1) | ||

| Yes | 4 (3.9) | 13 (4.4) | |

| Systemic infection | 2 (50) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Exacerbation of psychiatric disorder | 1 (25) | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (25) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Postictal psychosis | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Headache | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Metabolic derangement | 3 (23.1) | ||

ASM: antiseizure medications; ICU: intensive care unit; IES: isolated epileptic seizures; OR: odds ratio; SC: seizure clusters. Values shown in bold are statistically significant.

SC are frequent in patients visiting the emergency department due to epileptic seizures, with a prevalence of 21.2% in our cohort. Prevalence varies widely across studies, ranging from 13% to 76% in outpatient settings and from 14.9% to 57.1% in emergency departments.15–17 These disparities may be explained by the lack of standardization in the definition. In fact, studies using the same definition as our study report similar prevalence rates to our own: Sillanpää et al.18 and Chen et al.15 report prevalence estimates of 21.7% and 14.9%, respectively.

In our study, younger age, history of epilepsy, and previous treatment with three or more ASM were associated with increased risk of visiting the emergency room due to SC. Similarly, some studies have found that most patients visiting the emergency department due to SC have an existing diagnosis of epilepsy.19,20 The pathophysiological mechanisms of SC seem to be responsible for the higher frequency of this phenomenon in patients with history of epilepsy. This is consistent with evidence suggesting that seizures occurring within a short period of time usually originate from the same epileptogenic focus, which may become highly susceptible at a certain periodicity due to increased excitability or decreased inhibition.21 Probabilistic models have also supported this theory.4 This also reflects the chronic molecular changes in energy metabolism, receptors, and ion channels that lead to epilepsy, in contrast to seizures occurring in patients without history of the disease.22 Additionally, patients with SC were more likely to be receiving three or more ASM than those with IES (39.7% vs 28.1%; P=.046). This has been described as a feature of severe, drug-resistant epilepsy and has also been observed in other cohorts, along with such other markers as poor seizure control, history of status epilepticus, epilepsy-related hospitalizations, and multiple seizure types.8,15,17,23–25 Furthermore, in the cohort of Maliekal et al.,26 the likelihood of seizure clustering increased with each additional ASM. Regarding the younger age of patients with SC as compared to those with IES (32 vs 40; P=.028), this demographic characteristic has been reported in other studies, including a population-based study in which SC prevalence rates decreased with increasing age.16,27 The underlying mechanism explaining this phenomenon remains unclear and has been little explored in other cohorts. Furthermore, the median age of our cohort is consistent with those of other studies, reporting mean ages of 33–41 years.13

The most frequent etiology of SC among the patients with history of epilepsy was poor adherence to ASM. This is consistent with studies reporting high prevalence rates of SC in populations where ASM reduction or withdrawal has been described.20 In the cohort described by Szklener et al.,20 ASM withdrawal was a frequent etiology in the subgroup of patients with history of epilepsy. In the outpatient cohort described by Fisher et al.,28 missed medicine or medicine changes were identified as a trigger in 513 out of 12576 patients. In an epilepsy monitoring unit, 68% of cases of SC presented in the context of decrease or withdrawal of ASM.23,29 Despite the widespread availability of ASM, 30–60% of patients with epilepsy present poor adherence. Abrupt discontinuation of ASM poses a significant risk of SC, as it leads to a decrease in serum drug levels and, consequently, loss of seizure control.30,31 Evidence from a large-scale study suggests that nonadherence to ASM is associated with a 21% increase in the risk of seizures, underscoring the severe consequences of ASM discontinuation.32 This may be associated with a wide range of negative clinical outcomes, including increased risk of mortality, fractures, injuries, emergency department visits, and hospitalization.33

In our study, patients with SC presented longer hospital stays than those with IES (37.9 vs 26.8h; P=.005). However, we did not find statistically significant differences in the prevalence of complications, ICU admissions, or in-hospital seizure recurrence. In this scenario, it should be noted that all patients in the SC group received intravenous ASM. Although current guidelines provide no recommendations, this treatment approach is considered reasonable in our setting, as non-intravenous benzodiazepines are not available. This has been reported in previous studies. For example, Orlandi et al.14 evaluated the effectiveness of brivaracetam in this clinical scenario, reporting that seizure activity was controlled without the need for other rescue medication in 77% of their cohort. Eilam et al.13 analyzed the effectiveness of lacosamide in SC, reporting a high response rate at 89%. Although we did not directly analyze the effectiveness of intravenous ASM in this subgroup of patients, the absence of differences in hospitalization outcomes suggests that intravenous ASM may be beneficial. All the above may serve as a basis for intervention-based studies in our setting.

Lastly, we found that very few patients received pre-hospital seizure management. Although this may be explained by the lack of rapid-acting non-intravenous medications in our country, insufficient education of family members and pre-hospital care personnel may also play a role. In our study, only 9.7% of patients with SC received pre-hospital treatment (intravenous benzodiazepines or ASM in all cases), a considerably lower rate than those reported in other studies. Chen et al.15 and Detyniecki and Penovich8 reported rates of rescue medication use of 26.4% and 43.5%, respectively. This highlights the need to improve the design of structured outpatient management plans for family members and pre-hospital care personnel, as well as the selection of portable, easy-to-use, socially acceptable medications with favorable safety profiles.

Within this framework, there is growing interest in developing acute seizure action plans (ASAPs) including all stakeholders involved in the management of acute epileptic seizures, among which SC represent a significant concern. These interventions involve patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers, and are tailored to each patient's personal, cultural, legal, and regulatory context.6,34 Despite these efforts, several gaps remain, including the fact that only approximately30% of patients have an ASAP, the lack of awareness of scenarios that require early preventive treatment, and the limitations of the available rescue therapies.34–37 These limitations include variability in drug absorption via mucosal routes and uncertainty regarding the exact onset of anticonvulsant activity.35,36 Regarding the latter issue, ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of ASM administered via non-invasive routes that rapidly achieve systemic concentrations, aiming to terminate ongoing seizures and prevent recurrence.35

One limitation of this study is the possibility of selection bias, as this cohort was drawn from a single hospital providing care to patients in a specific socioeconomic context. Furthermore, the inclusion of patients exclusively from a hospital setting limits the generalizability of our findings to other contexts, such as the outpatient setting, where SC are also prevalent. In addition, we were unable to fully characterize patients’ epilepsy in terms of etiology, epileptogenic zone, or presence of specific epileptic encephalopathies or syndromes, which is particularly relevant given the well-known increase in the risk of SC among patients with epileptic encephalopathies. The heterogeneity of our sample prevented us from performing subgroup analyses comparing patients with epileptic encephalopathies or epilepsy syndromes. Finally, the lack of a standardized definition for SC may limit comparisons with other cohorts.

ConclusionSC are common in emergency departments, with a prevalence of 21.2% in a tertiary hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. They are most frequently observed in patients of younger age, with history of epilepsy, and using three or more ASM. In our population, the main etiology was poor treatment adherence. Furthermore, very few patients received treatment prior to arrival at hospital. This highlights the urgent need for educational strategies aiming to improve adherence to ASM and to design ASAP to minimize the risk of poor outcomes in these patients.

Ethical approvalResearch Ethics Committee of the Southwest Subnetwork E.S.E – approval number 6 of 2024.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.