Stroke is a time-dependent neurological disease. Health District V in the Murcia Health System has certain demographic and geographical characteristics that make it necessary to create specific improvement strategies to ensure proper functioning of code stroke (CS). The study objectives were to assess local professionals’ opinions about code stroke activation and procedure, and to share these suggestions with the regional multidisciplinary group for code stroke.

Subjects and methodThis cross-sectional and descriptive study used the Delphi technique to develop a questionnaire for doctors and nurses working at all care levels in Area V. An anonymous electronic survey was sent to 154 professionals. The analysis was performed using the SWOT method (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats).

ResultsResearchers collected 51 questionnaires. The main proposals were providing training, promoting communication with the neurologist, overcoming physical distances, using diagnostic imaging tests, motivating professionals, and raising awareness in the general population.

ConclusionsMost of the interventions proposed by the participants have been listed in published literature. These improvement proposals were forwarded to the Regional Code Stroke Improvement Group.

El ictus es una patología neurológica tiempo dependiente. El Área V de salud de la Región de Murcia posee unas determinadas características demográficas y geográficas que hacen imprescindible la creación de propuestas de mejora concretas para garantizar un correcto funcionamiento del código ictus. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron valorar la opinión de los profesionales del Área respecto a la activación y la práctica del mismo y compartir esas propuestas de mejora con el grupo multidisciplinar de mejora del código ictus regional.

Sujetos y métodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal, utilizando la técnica Delphi para elaborar un cuestionario dirigido al personal médico y de enfermería de todos los niveles asistenciales. El cuestionario era anónimo y de cumplimentación telemática; se envió a 154 profesionales. El análisis se realizó con el método DAFO (debilidades, amenazas, fortalezas y oportunidades de mejora).

ResultadosSe recogieron 51 cuestionarios. Las propuestas de mejora principales fueron: la formación, la comunicación con el neurólogo, la distancia, las pruebas de imagen, la motivación a los profesionales y la concienciación a la población general.

ConclusionesEn la bibliografía actual, se recogen la mayoría de las intervenciones que propusieron los participantes. Las propuestas de mejora se transmitieron al grupo de Mejora del Código Ictus de la Región de Murcia.

Stroke, also known as cerebrovascular accident, is characterised by sudden neurological deficits due to ischaemia or haemorrhage in the central nervous system. Stroke is a neurological emergency given that lesion mechanisms secondary to cerebral ischaemia progress very quickly and treatments may only be effective during a short period of time.1 Ischaemic stroke is caused by focal vascular occlusion leading to a decrease in oxygen and glucose flow to the brain, resulting in interrupted metabolic activity in the affected territory. This type of stroke accounts for 80% to 85% of all stroke cases.2 All patients should have easy access to diagnostic techniques and effective treatments during the acute phase. Advances in stroke management revolve around the pillars of early neurological care, admission to stroke units, fibrinolytic treatment for cerebral infarction, and rehabilitation.3 Healthcare systems must act as early as possible to provide each patient with the best treatment option and guarantee equal care for all stroke patients.4 ‘Code stroke’ reduces attention times and treatment delays.1,5 The chain of stroke care begins when the patient and/or family identifies stroke symptoms and recognises an emergency, followed by pre-hospital assistance and/or medical care at the emergency department, assessment, and treatment.6,7 The therapeutic window is narrow both for intravenous systemic fibrinolysis (thrombolytic treatment with tissue plasminogen activator or t-PA) and for mechanical thrombectomy. Treatment is most effective when administered within the first 60minutes after stroke onset; this time frame has been associated with better outcomes. Cooperation among regional services delivers rates of thrombolytic treatment that are higher than those from local services working individually. Treatment for acute ischaemic stroke reduces disability rates and healthcare costs. However, the infrastructure necessary to provide this treatment is complex since it integrates multiple levels of care: in-hospital and non-hospital emergency services, the radiology department, and the neurology department (stroke team).8

A protocol for code stroke, implemented in the Spanish province of Murcia9 in 2009, integrated the following steps: establishing a stroke unit at Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca and Hospital de Santa Lucía; training clinicians and nursing staff from the hospital services caring for stroke patients; training clinicians and nursing staff at other care levels (primary care, non-hospital emergency services, emergency departments, internal medicine departments, neurology departments of hospitals with no thrombolytic therapy); training other local and regional healthcare professionals; providing fibrinolysis capability during the morning shift at hospitals in other healthcare districts; and analysing the effectiveness of the protocol. The Regional Code Stroke Improvement Group was created in 2014 and included representatives from all health districts in the province of Murcia. The purpose of this group was to set up a multidisciplinary team that would provide continuous assessment of code stroke measures and promote training, educational, and organisational initiatives able to make it more effective at all levels.

According to the 2013 census, Murcia Health District V covers a population of 62103 inhabitants.10 It comprises 3 subdistricts (Yecla-Este, Yecla-Oeste, and Jumilla) and its hospital of reference is Hospital Virgen del Castillo in Yecla. Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca is the centre of reference for fibrinolysis. Apart from the hospital, Murcia Health District V has 2 medical emergency units, one in Yecla and the other in Jumilla, and 2 primary care emergency services. Their characteristics may impact the care provided to stroke patients: physical distance from the reference hospital with a stroke unit, lack of an on-call neurology service, inability to provide neurologist-supervised thrombolytic treatment during morning shifts from Monday to Friday, lack of stroke and intensive care units, type of triage at the hospital's emergency department, dimensioning for 62000 inhabitants according to the census although there are also 10000 unregistered inhabitants, limited human, material, and economic resources, etc. Given that some of these characteristics cannot be changed, designing ‘realistic’ proposals for improvement is essential for the creation of an effective care system. We decided to analyse the actual situation by sending an opinion survey to all healthcare professionals who might activate code stroke due to having contact with potentially susceptible patients. We used SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) to frame a practical and optimistic approach.11

Our main purpose was to determine the level of knowledge of code stroke among healthcare professionals in Murcia Health District V who may have to attend patients with suspected stroke, and therefore activate code stroke, in order to design improvement strategies. As a secondary objective, we aimed to share the results of our analysis with the multidisciplinary Regional Code Stroke Improvement Group in order to identify strengths, determine opportunities for cooperative efforts, and evaluate whether this survey may be applicable to other health districts in Murcia. Numerous studies have shown that cooperation between local and regional services achieves better results.12

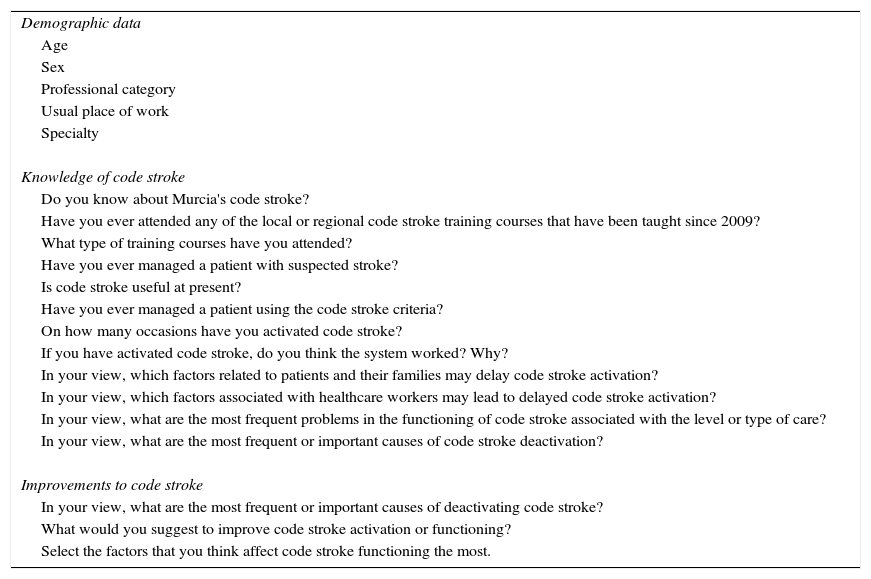

Patients and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study in primary care, specialised care, non-hospital emergency services, and hospital emergency departments. Since the literature search returned no questionnaires validated for the same purposes as those of our study, we designed our own questionnaire using the Delphi method.13 Our search strategy was to gather all articles published in either English or Spanish between January 2009 and November 2014 and included in Medline or Embase. We designed a 15-item survey (Table 1) which was sent by e-mail to all participants; it had to be completed online and was anonymous. The survey was sent to 154 healthcare professionals: directors and deputy directors of medical departments and nursing units, primary care physicians, professionals from primary care emergency services, first responders, and clinicians representing emergency departments, radiology, and internal medicine. Our study was conducted as follows: literature search; designing the survey based on the Delphi method; contacting and informing the hospital's advisory board and ethics committee; obtaining permission to conduct the study; contacting the head of the nursing staff and professionals from non-hospital emergency services, healthcare centres, hospital emergency department, and internal medicine department (including neurologists); gathering participants’ e-mail addresses; sending the survey; analysing results; and suggesting improvements.

Items in the survey.

| Demographic data |

| Age |

| Sex |

| Professional category |

| Usual place of work |

| Specialty |

| Knowledge of code stroke |

| Do you know about Murcia's code stroke? |

| Have you ever attended any of the local or regional code stroke training courses that have been taught since 2009? |

| What type of training courses have you attended? |

| Have you ever managed a patient with suspected stroke? |

| Is code stroke useful at present? |

| Have you ever managed a patient using the code stroke criteria? |

| On how many occasions have you activated code stroke? |

| If you have activated code stroke, do you think the system worked? Why? |

| In your view, which factors related to patients and their families may delay code stroke activation? |

| In your view, which factors associated with healthcare workers may lead to delayed code stroke activation? |

| In your view, what are the most frequent problems in the functioning of code stroke associated with the level or type of care? |

| In your view, what are the most frequent or important causes of code stroke deactivation? |

| Improvements to code stroke |

| In your view, what are the most frequent or important causes of deactivating code stroke? |

| What would you suggest to improve code stroke activation or functioning? |

| Select the factors that you think affect code stroke functioning the most. |

According to the Spanish Organic Law 15/1999 of 13 December for the Protection of Personal Data,14 personal data and survey responses were kept in strict confidentiality. Healthcare professionals participated voluntarily. We gathered participants’ e-mail addresses from records kept by supervisors/coordinators of each department/service and provided information about the aims of our study.

The main types of systematic error in our study were information bias and selection bias (self-selection bias). Information bias was due to the fact that there are no validated questionnaires for the purposes of our study. To avoid measurement errors in some variables, a group of experts from our health district and working at the hospital with the reference stroke unit designed a questionnaire using the Delphi method. To avoid selection biases, we included all professionals who may have to manage stroke at some point and working for non-hospital and hospital emergency services. The coordinators of these teams were contacted and informed about the study and invited to participate. The e-mail highlighted the importance of participating even if recipients had never managed a stroke patient. E-mails were sent on 2 occasions; surveys were expected to be completed within the first 15 and 7 days from receipt, respectively.

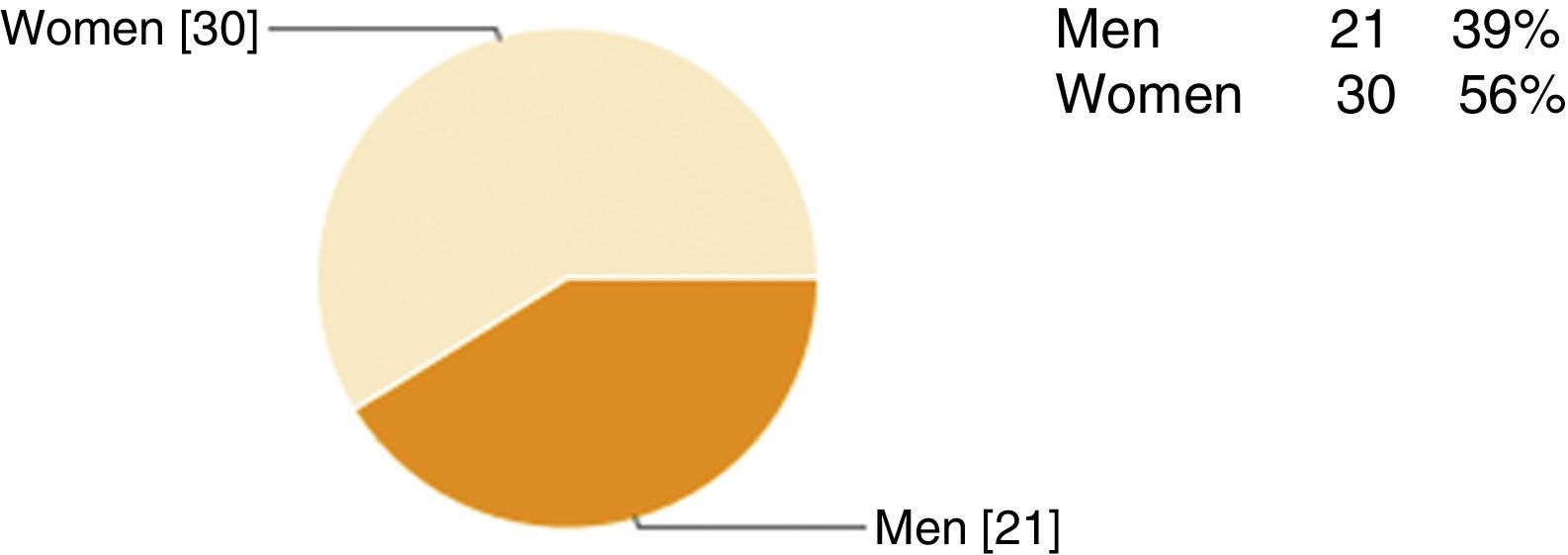

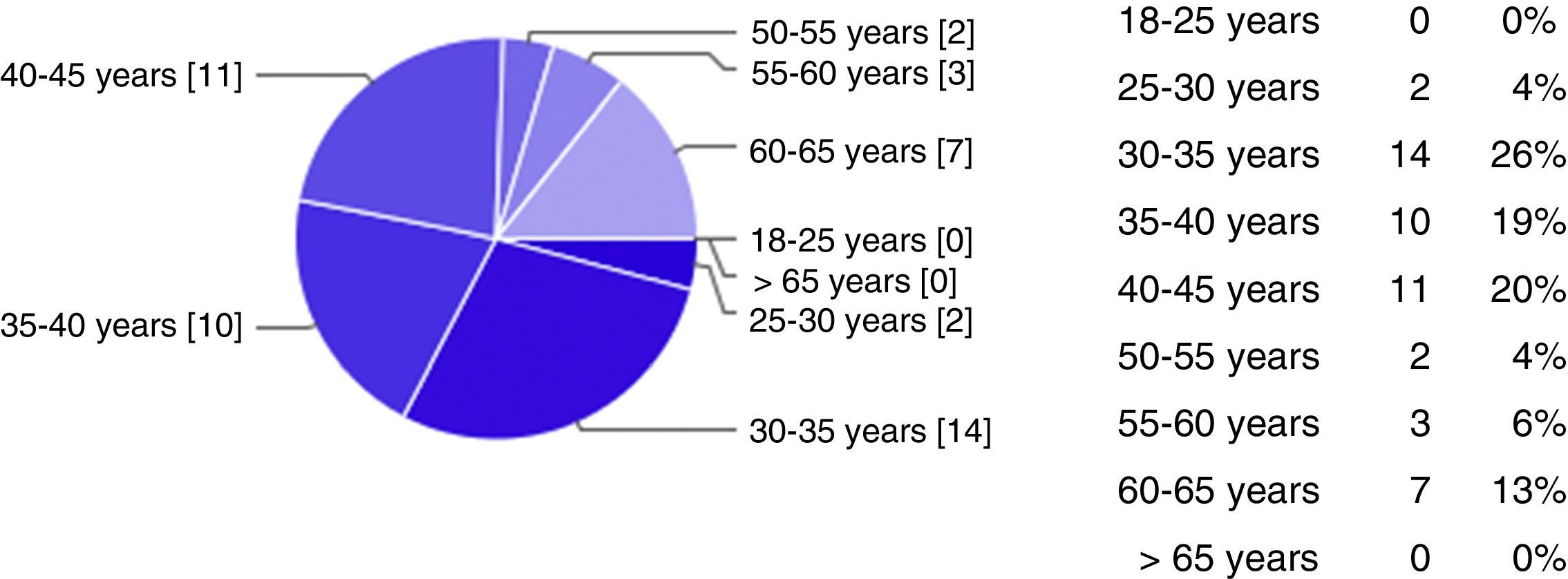

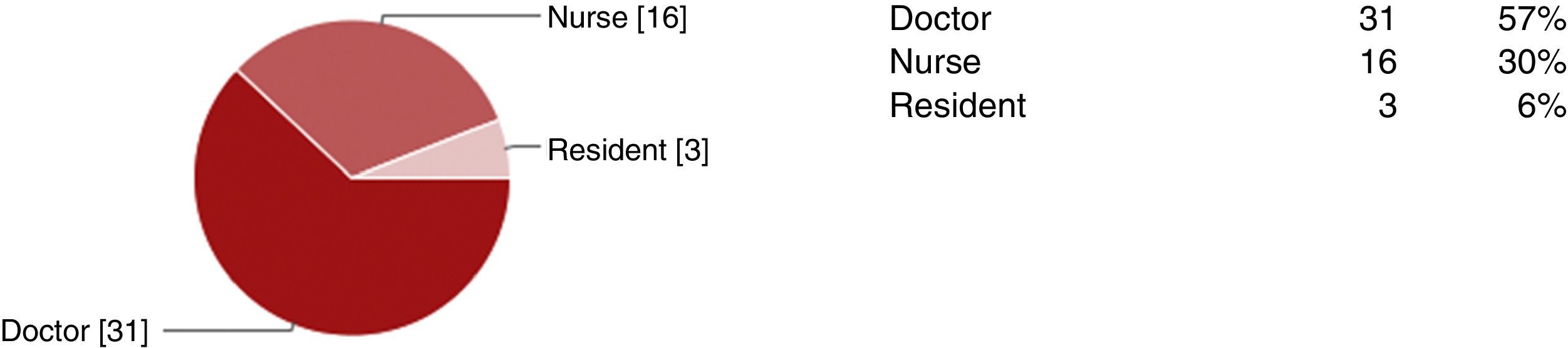

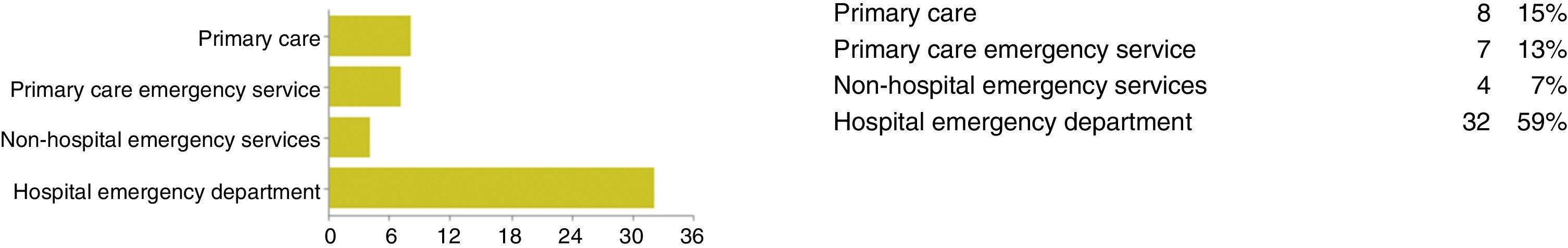

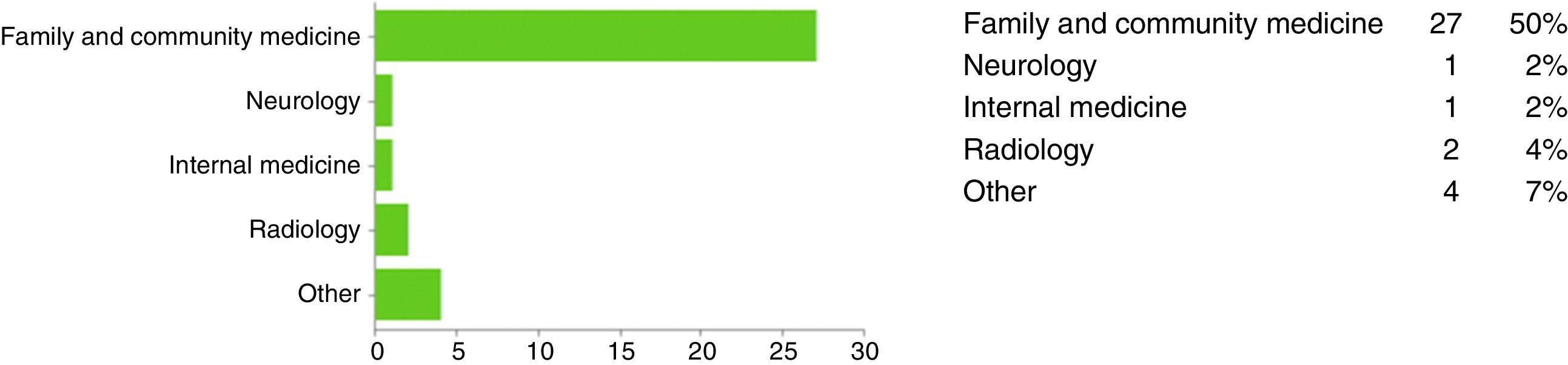

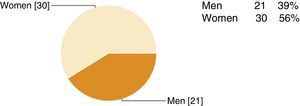

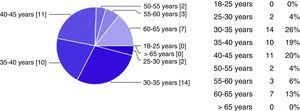

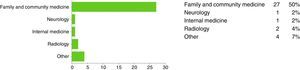

Results and discussionOur survey was sent to 154 healthcare professionals, 51 of whom completed it. Figs. 1–5 summarise participants’ demographic data. All respondents knew that a code stroke protocol had been implemented in the province of Murcia. Some 65% of the participants had received some type of training on code stroke, 90% had managed stroke patients, and 82% had activated code stroke (86% on 0-10 occasions, 12% on 10-20 occasions); nearly two thirds of the participants felt that the code stroke protocol was effective (73%). According to the participants, the following elements of code stroke should be improved: lack of knowledge of how code stroke functions (23%), communication with the neurologist at the hospital with a stroke unit (19%), significant care burden (13%), code stroke activation during night shifts (10%), dispatch of ambulances and the response team (10%), delays in performing complementary radiology tests (10%), communication with the emergency telephone service (7%), delays in obtaining laboratory test results (5%), and others (1.1%). The most frequent or important causes of code stroke deactivation were as follows: older age, clinical progression times of 3-3.5hours (leaving no time to reach a hospital with a stroke unit for treatment with intravenous fibrinolysis within the 4.5 hour window), a history of neurological diseases, haemorrhagic stroke, and high mRS scores. We will now address participants’ impressions on their own knowledge of code stroke. When participants were asked whether the system worked and why, they identified the following strengths: early recognition of symptoms by patients or their families, adherence to time recommendations, correct activation, good communication, cooperation between professionals, existence of protocols, motivation of professionals, early identification of symptoms, effective management by the neurologist at the hospital with a stroke unit, and improved time management. The following weaknesses and threats were identified: inability to identify symptoms, deficient anamnesis and/or physical examination, delays in patient transfer, and the impression that code stroke was not activated for patients who would have been eligible for fibrinolysis. According to participants, the following factors having to do with patients or their families were likely to affect code stroke activation: lack of knowledge of stroke symptoms or the existence of code stroke, unawareness of the direct correlation between time to care and severity of sequelae, lack of information, patient vulnerability (elderly patients living alone, carers not paying attention to patients’ self-reported non-specific symptoms), and distance to the hospital with a stroke unit. The factors related to healthcare professionals and able to delay code stroke activation were the following: lack of knowledge of the protocol and inclusion and exclusion criteria for code stroke, the medical questions posed to the patient and family, training, diagnostic difficulty, each professional's subjective view, lack of expertise, lack of knowledge of available techniques, lack of physical resources, result of triage, lack of human resources, unnecessary/inappropriate referral, communication among professionals, and distance to the hospital with a stroke unit. The most frequent problems with code stroke at the departmental/service level were as follows: errors in initial assessment (out of hospital and in-hospital), lack of initial assessment by a neurologist (diagnostic uncertainty), lack of coordination between care levels, lack of communication with the neurologist at the hospital with a stroke unit, delays in initial assessment/management, performing an initial CT when a CT scan will be ordered at the hospital with a stroke unit anyway, inability to view the CT image electronically from the reference hospital, physical distance to the reference hospital (mean transfer time by highway is 1.15-1.30hour), human resources (laboratory technicians, nurses, orderlies), and the elevated care burden on non-hospital emergency services and hospital emergency departments.

The suggestions for improving code stroke activation or functioning coincide with those published in the literature: better awareness of the link between time and brain damage; better awareness of the code stroke protocol; theoretical training including multidisciplinary clinical cases and practical exercises; continuing education, training for new professionals, and periodic refresher courses; answering questions about training (is it mandatory? should it be conducted during working hours?); communication with the neurologist (telephone number; presence of a single informant; patient referral when in doubt; formal explanations for code stroke deactivation); overcoming distance (confirming criteria for code stroke activation before referral, using helicopters when the window of opportunity is closing, faster transportation, managing bureaucracy related to referrals); imaging techniques (availability of functional tests, possibility of viewing our hospital's CT images from a reference hospital, determining whether CT scans should be conducted at the first hospital or the one with a stroke unit [time between initial CT scan and arrival at the stroke unit is approximately 1.5hour]); informing the general population about stroke symptoms; and motivating professionals.

Although all professionals were aware of code stroke, further training is necessary. Training should be practical, include clinical cases, establish a standard neurological examination, inform about existing protocols, and be updated regularly. Training may also help motivate healthcare professionals, even those not participating in the survey. Communication also needs improvement since stroke patients may be attended at any care level. Given the heavy care burden and triage problems in hospital emergency departments, we suggest creating the figure of ‘stroke coordinator’ for each hospital and shift (either a nurse or a doctor with specific training in code stroke). This expert would identify cases that may meet criteria for stroke and accelerate the care process. Raising awareness about stroke symptoms among the general population and healthcare professionals is essential for early treatment; this is especially relevant in healthcare districts located far away from the hospital with a stroke unit, where stroke management times must be optimised. Raising awareness of stroke symptoms among the general population is another strategy that may improve access to thrombolytic treatment. Other studies have concluded that pre-hospital code stroke, combined with awareness campaigns for the general population, improves rates of early thrombolysis.15,16

According to our literature search, no studies have addressed the contents or frequency of these campaigns. Helicopter use should be included in the protocol for code stroke, and hospital systems for acute stroke management will have to be reorganised to this end.17

We shared our results with the members of the Regional Code Stroke Improvement Group in order to design measures that may improve management times or systems in the context of code stroke.

With a view to improving code stroke strategies, we suggest conducting another study to estimate stroke prevalence in Murcia Health District V, analyse patient characteristics, improve the quality of care, and determine if there are variables predicting the likelihood of stroke patients receiving thrombolytic therapy.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Drs María Jesús Aguilera, Enrique Retuerto, Reinerio Figueroa, Araceli Bernal, and Ana Morales for their help in designing the survey, as well as all the doctors and nurses who completed it.

Please cite this article as: González-Navarro M, Martínez-Sánchez MA, Morales-Camacho V, Valera-Albert M, Atienza-Ayala SV, Limiñana-Alcaraz G. Encuesta de opinión sobre propuestas de mejora del código ictus en el Área V de la Región de Murcia, 2014. Neurología. 2017;32:224–229.

This study has not been presented at the SEN's Annual Meeting or at any other conferences or congresses.