Parkinson disease (PD) is clinically defined as the presence of the so-called cardinal motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability.1 In addition, a plethora of non-motor symptoms can occur with the passage of time including cognitive decline and abnormal behavior.1 PD is generally an irreversible and progressive condition as most symptoms such as bradykinesia and postural reflexes inexorably worsen. Occasionally, however, some symptoms may evolve in less predictable fashion. Tremor is the only cardinal parkinsonian symptom that can improve or even remit, although this fact has been only occasionally mentioned.1–4 In this short review, we summarize what is known about the reversibility of parkinsonian tremor, and speculate on the mechanisms of this rare but fascinating phenomenon.

Tremor may be considered peculiar among classical motor symptoms, since its evolution is variable,1–4 its response to levodopa unpredictable,4 and its relationship with dopaminergic deficiency is rather weak.5,6 Rest tremor is inversely correlated with serotonin transporter availability.7 In addition, parkinsonian tremor is mediated by a distinct metabolic network involving cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways.8 In any case, the natural evolution of parkinsonian tremor is highly unpredictable, as it can become exacerbated over time, stabilize, improve, and, though rarely, even disappear.1–4 The remission of parkinsonian tremor is not entirely exceptional however; Hughes et al., in their classic article observed that “nine patients lost their tremor late in the disease”1 and Toth et al. already noted the disappearance of rest tremor in 15 patients over an average of 7.1 years after onset.3

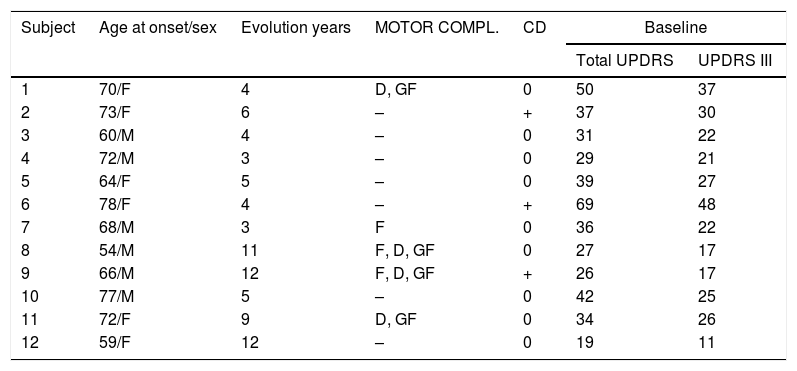

We identified a group of patients with evident and confirmed resting tremor (accompanied or not by positional tremor) at onset (minimum score of 2 points according to the tremor items of the UPDRS III) and confirmed remission of tremor on subsequent evaluations. We defined tremor remission as the objective and subjective disappearance of previous tremor (Score items: 0). This group of patients was extracted retrospectively from a series of patients followed at our institution over the last 30 years.9,10Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of this group of patients. All our patients were treated with levodopa and at least one ancillary antiparkinsonian medication such as dopamine agonist and or IMAO. Due to the rarity of complete parkinsonian tremor remission (12 patients), comparison with patients not manifesting remission is obviously incomplete, but these patients were older compared to a control PD group with similar follow-up assembled from our general PD database (mean age at start: 67±7.3 vs 58.5±10.21 years; P<0.001 t test). It is difficult to isolate a set of shared characteristics among this group of patients: some could be defined as advanced PD due to the presence of motor complications and/or cognitive decline (cases 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11), but some other patients exhibited mild PD without relevant complications (case 12). The time period from the disease onset to tremor remission was variable, ranging from 3 to 12 years.

Tremor remission in Parkinson's disease.

| Subject | Age at onset/sex | Evolution years | MOTOR COMPL. | CD | Baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total UPDRS | UPDRS III | |||||

| 1 | 70/F | 4 | D, GF | 0 | 50 | 37 |

| 2 | 73/F | 6 | – | + | 37 | 30 |

| 3 | 60/M | 4 | – | 0 | 31 | 22 |

| 4 | 72/M | 3 | – | 0 | 29 | 21 |

| 5 | 64/F | 5 | – | 0 | 39 | 27 |

| 6 | 78/F | 4 | – | + | 69 | 48 |

| 7 | 68/M | 3 | F | 0 | 36 | 22 |

| 8 | 54/M | 11 | F, D, GF | 0 | 27 | 17 |

| 9 | 66/M | 12 | F, D, GF | + | 26 | 17 |

| 10 | 77/M | 5 | – | 0 | 42 | 25 |

| 11 | 72/F | 9 | D, GF | 0 | 34 | 26 |

| 12 | 59/F | 12 | – | 0 | 19 | 11 |

MOTOR COMPL.: motor complications; F: fluctuations; GF: gait freezing; D: dyskinesias; CD: cognitive decline.

In essence, parkinsonian tremor remission is not an exceptional finding in PD, although this may be unnoticed by the patients, embarrassed by other, much more disabling symptoms (including motor, non-motor fluctuations, freezing of gait, loss of postural reflexes or cognitive decline)

There are several explanations for these intriguing observations. The mechanism by which parkinsonian tremor may occasionally improve or even disappear is unknown; but Tzoulis et al. proposed a very attractive explanation, pondering the reason why patients with polymerase gamma mutations did not develop significant parkinsonism in spite of severe nigral degeneration.11 The authors suggested that concurrent lesions or dysfunction in other neuroanatomical structures and pathways (dysfunction of the cerebellum and/or its connections) can modulate the function of the basal ganglia and may compensate clinical parkinsonism in polymerase gamma mutation carriers.11 Similarly, we could speculate that in some PD patients, dysfunction in several thalamic nuclei may explain the improvement or even remission of parkinsonian tremor. Thalamic median-parafascicular complex nuclei can also be affected in PD12; interestingly, deep-brain stimulation of the median-parafascicular complex has been suggested as treatment for tremor control in PD.13

Finally, in addition to parkinsonian tremor, several reports suggest that some other parkinsonian features such as REM behavior disorders and gait freezing may exceptionally improve spontaneously or even disappear.14–17

In any case we understand that the evidence of this topic is very limited, and our conjectures are highly speculative; and even we consider that some apparent remissions may result from limitations in the rating scales or tools used to assess patients. But after all, there are several reports suggesting that remission of parkinsonian tremor occasionally occur, and this rare but fascinating phenomenon may raise several aspect of neurodegeneration including the role of neuroplasticity and the existence of compensating lesions and dysfunction over time

Author roles(1) Research project: (A) conception, (B) organization, (C) execution; (2) statistical analysis: (A) design, (B) execution, (C) review and critique; (3) manuscript preparation: (A) writing of the first draft, (B) review and critique.

P.J.G.R.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A; M.R.L.: 1C, 2C, 3B; C.F.: 1C, 2C, 3B.

Ethical compliance statementThe authors confirm the approval of our institutional review board written informed consent was not necessary.

Financial disclosures for previous 12 monthsPJGR received research support from Allergan and UCB, personal compensation as a consultant/scientific advisory board from Italfarmaco, Britannia, Bial, and Zambon and speaking honoraria from Italfarmaco, UCB, Zambon, Allergan, and Abbvie. CF and MRL: no disclosures to report.

FundingNo specific funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.

We appreciate the editorial assistance of Dr Oliver Shaw.