Ataxia with downbeat nystagmus (A-DBN) has recently been associated with an intronic GAA repeat expansion in the FGF14 gene. The objectives of our study were to describe the clinical, radiological, and genetic findings, as well as the long-term response to aminopyridine (AP) treatment, in a cohort of patients with ataxia with DBN.

MethodsDemographic, clinical, and radiological data were obtained through medical records. Genetic analysis of the FGF14 GAA expansion was performed. All patients were under compassionate treatment with AP. Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) score pre-treatment was compared with the current SARA score. Patient Clinical Global Impression (CGI-p) and the presence of adverse events were also assessed.

ResultsEight patients were included. Median (quartiles 1 and 3) age at disease onset was 63.5 (54–67) years. Before treatment, patients complained of gait instability with daily fluctuations and visual disturbances. They showed DBN with predominant involvement of gait and posture on the SARA. Brain MRI disclosed mainly vermian atrophy. An FGF14 GAA expansion (>250 repeats) was demonstrated in all patients. After a median AP treatment duration of 43 (14.25–137.25) months, the CGI-p showed a median improvement of 65% (60–80%) in their disability, and the total SARA score remained without significant changes (P=.348). Only one patient complained of transient gastric upset and nausea with AP treatment.

ConclusionsPatients with A-DBN due to the FGF14 GAA expansion predominately show an axial involvement with fluctuating disability. Long-term treatment with AP is well tolerated and effective, and seems to slow disease progression in our patients.

La ataxia con nistagmo vertical hacia abajo (A-DBN) se ha asociado recientemente con una expansión intrónica de repeticiones GAA en el gen FGF14. Nuestros objetivos fueron describir los hallazgos clínicos, radiológicos y genéticos, así como la respuesta a largo plazo al tratamiento con aminopiridinas (AP), en una cohorte de pacientes con A-DBN.

MétodosLos datos demográficos, clínicos y radiológicos se obtuvieron a través de las historias clínicas. Se realizó un análisis genético de la expansión GAA en FGF14. Todos los pacientes estaban en tratamiento compasivo con AP. La puntuación de la escala SARA pretratamiento se comparó con la puntuación actual. También se evaluó la impresión clínica global del paciente (CGI-p) y la presencia de eventos adversos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron ocho pacientes. La mediana (IQR) de la edad de inicio de la enfermedad fue de 63,5 (54-67) años. Antes del tratamiento, los pacientes se quejaban de inestabilidad en la marcha con fluctuaciones diarias y alteraciones visuales. En el examen mostraban DBN con afectación predominante de la marcha y la postura en la SARA. La RM cerebral evidenció principalmente atrofia vermiana. En todos los pacientes se demostró una expansión de GAA>250 repeticiones. Después de 43 meses (14,25-137,25) de tratamiento con AP, la CGI-p mostró una mejoría del 65% (60%-80%). La puntuación total de la SARA se mantuvo sin cambios significativos (p=0,348). Sólo un paciente refirió malestar gástrico transitorio y náuseas con el tratamiento con AP.

ConclusionesLos pacientes A-DBN debido a la expansión GAA en FGF14 muestran predominantemente una afectación axial con discapacidad fluctuante. El tratamiento a largo plazo con AP es bien tolerado, eficaz y parece enlentecer la progresión de la enfermedad en nuestros pacientes.

Downbeat nystagmus (DBN) is the most common form of acquired fixation nystagmus, often causing oscillopsia and blurred vision.1 DBN is frequently associated with gait and postural instability, which cannot be explained solely by impairment of visual control but mainly by vestibulo-cerebellar dysfunction, as suggested by posturography and gait studies.2,3 In fact, the presence of cerebellar atrophy on brain MRI in most patients with DBN points to a primary cerebellar disorder.3,4

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) conducted in patients with DBN of unknown cause showed a significant association with a variation in intron 1 of the fibroblast growth factor 14 gene (FGF14).5 Recently, an intronic GAA repeat expansion in the FGF14 gene was shown to be a common cause of late-onset cerebellar ataxia (spinocerebellar ataxia 27B; GAA-FGF14 ataxia).6,7 Interestingly, different phenotypes can be delineated in carriers of the GAA-FGF14 expansion, based on the presence of different combinations of ataxia, DBN, other cerebellar ocular symptoms, or extracerebellar symptoms such as bilateral vestibulopathy and/or polyneuropathy.8

On the other hand, observational and randomized placebo-controlled studies have shown that aminopyridines (AP) are not only useful for the symptomatic treatment of Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome and gait ataxia in multiple sclerosis,9–11 but they are also effective treatments for DBN12–16 and episodic ataxia type 2.17–19 More recently, several open-label case series have shown promising benefits of 4-AP in SCA27B.8,20,21

This study aimed to clinically, radiologically, and genetically characterize a cohort of patients with ataxia associated with DBN, and to assess their long-term treatment response to AP.

Material and methodsPatientsWe enrolled a consecutive series of 8 patients with ataxia associated with DBN that had been referred to our hospital's neurology outpatient clinic between 2008 and 2020. All of them were under compassionate treatment with AP by medical decision. Prior to treatment initiation, we had conducted a comprehensive assessment to confirm the absence of contraindications (e.g., asthma, convulsions, liver problems) and ensure that renal function (creatinine and glomerular filtration rate) and electrocardiography activity were normal.10 The study was approved by our center's ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Study designThe study had an ambispective design. Demographic, clinical, radiological, and previous genetic data, and scores on the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) before treatment were gathered retrospectively. Current SARA score and the Patient Clinical Global Impression (CGI-p) were obtained prospectively. SARA score before treatment was compared with the current SARA score. A visual analog scale ranging from 0 (no improvement) to 10 (no symptoms) was used to assess CGI-p; results were considered to reflect the subjective percentage of improvement in their disability. Adverse events of treatment were also recorded.

Genetic assessmentThe FGF14 repeat locus was genotyped by capillary electrophoresis of fluorescent long-range PCR amplification products and bidirectional repeat-primed PCRs targeting the 5′-end and the 3′-end of the locus to ascertain the presence of a GAA repeat expansion, as described previously.22 Results of fragment length analysis were validated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed. The different variables were expressed as median and quartiles 1 and 3 (Q1–Q3). We compared SARA score prior to AP treatment with the current SARA score using the Wilcoxon test. We also used the Spearman test to assess correlations between the age at onset and number of GAA repeats.

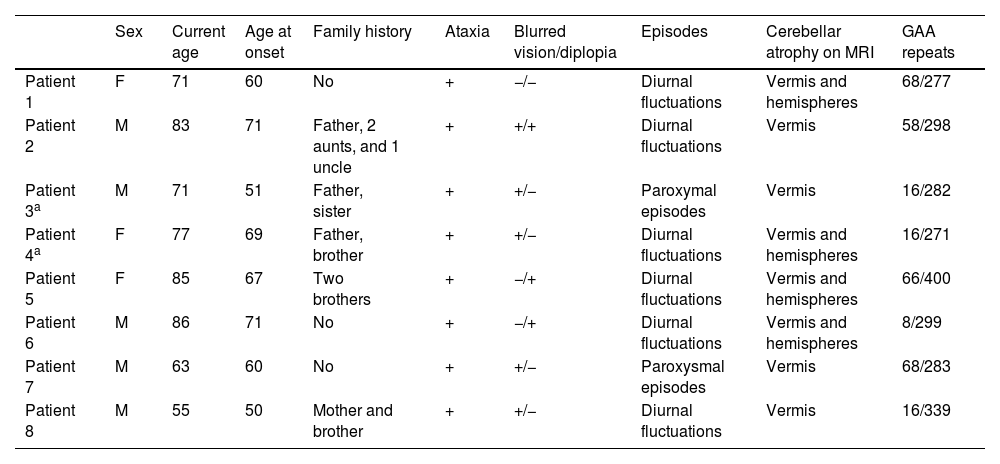

ResultsThe main results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Patients’ demographic, clinical, radiological, and genetic data.

| Sex | Current age | Age at onset | Family history | Ataxia | Blurred vision/diplopia | Episodes | Cerebellar atrophy on MRI | GAA repeats | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | F | 71 | 60 | No | + | −/− | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis and hemispheres | 68/277 |

| Patient 2 | M | 83 | 71 | Father, 2 aunts, and 1 uncle | + | +/+ | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis | 58/298 |

| Patient 3a | M | 71 | 51 | Father, sister | + | +/− | Paroxymal episodes | Vermis | 16/282 |

| Patient 4a | F | 77 | 69 | Father, brother | + | +/− | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis and hemispheres | 16/271 |

| Patient 5 | F | 85 | 67 | Two brothers | + | −/+ | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis and hemispheres | 66/400 |

| Patient 6 | M | 86 | 71 | No | + | −/+ | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis and hemispheres | 8/299 |

| Patient 7 | M | 63 | 60 | No | + | +/− | Paroxysmal episodes | Vermis | 68/283 |

| Patient 8 | M | 55 | 50 | Mother and brother | + | +/− | Diurnal fluctuations | Vermis | 16/339 |

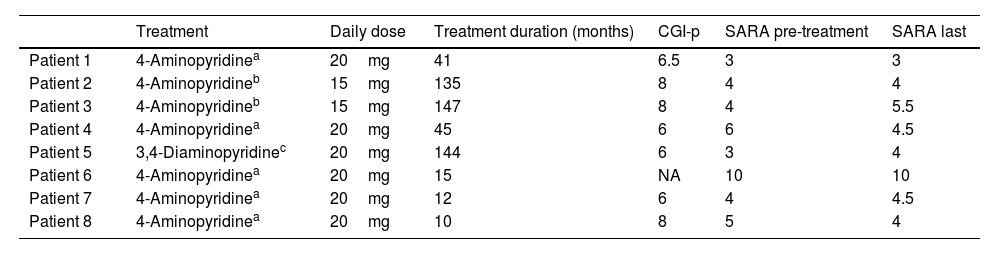

Treatment with aminopyridines.

| Treatment | Daily dose | Treatment duration (months) | CGI-p | SARA pre-treatment | SARA last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 4-Aminopyridinea | 20mg | 41 | 6.5 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient 2 | 4-Aminopyridineb | 15mg | 135 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Patient 3 | 4-Aminopyridineb | 15mg | 147 | 8 | 4 | 5.5 |

| Patient 4 | 4-Aminopyridinea | 20mg | 45 | 6 | 6 | 4.5 |

| Patient 5 | 3,4-Diaminopyridinec | 20mg | 144 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Patient 6 | 4-Aminopyridinea | 20mg | 15 | NA | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 7 | 4-Aminopyridinea | 20mg | 12 | 6 | 4 | 4.5 |

| Patient 8 | 4-Aminopyridinea | 20mg | 10 | 8 | 5 | 4 |

Five men and 3 women were included. Median age at inclusion was 74 (69–83.5) years. Median age at disease onset was 63.5 (54–67) years.

Clinical and radiological findingsAll patients complained of gait instability with daily fluctuations. Five patients presented with blurred vision, one of whom also complained of diplopia; 2 patients had mild diplopia and one patient did not complain of visual disturbances. Overall, patients reported feeling worse in the morning, with greater difficulty walking due to increased gait instability and visual disturbances. Patients 3 and 7 described frequent disabling paroxysmal episodes of worsening of ataxic and visual symptoms, associated with dizziness and dysarthria, lasting from minutes to several hours. In patient 7, these exacerbations coincided with exercise in the morning (e.g., going for a walk), while in patient 3, a trigger for these episodes could not be identified. No patient reported symptoms suggestive of extracerebellar involvement, such as urinary disturbances or sensory symptoms.

On examination before initiation of AP treatment, all patients showed predominant DBN on lateral gaze. Five patients had DBN on primary gaze. Three patients also had DBN on downward gaze, one patient on upward and downward gaze, and one patient only on upward gaze. The total SARA score was low (median: 4 [3.75–5.25]) and showed mainly gait and postural involvement with altered heel-shin slide maneuver. Sensory examination and deep tendon reflexes were normal in all but one of the patients (patient 6). This patient was the most affected by the disease in our series (SARA score: 10) and presented lymphoma, which required chemotherapy and radiotherapy. He had weak patellar reflexes, while ankle reflexes were abolished, and sensory examination showed decreased superficial and deep sensation in both legs.

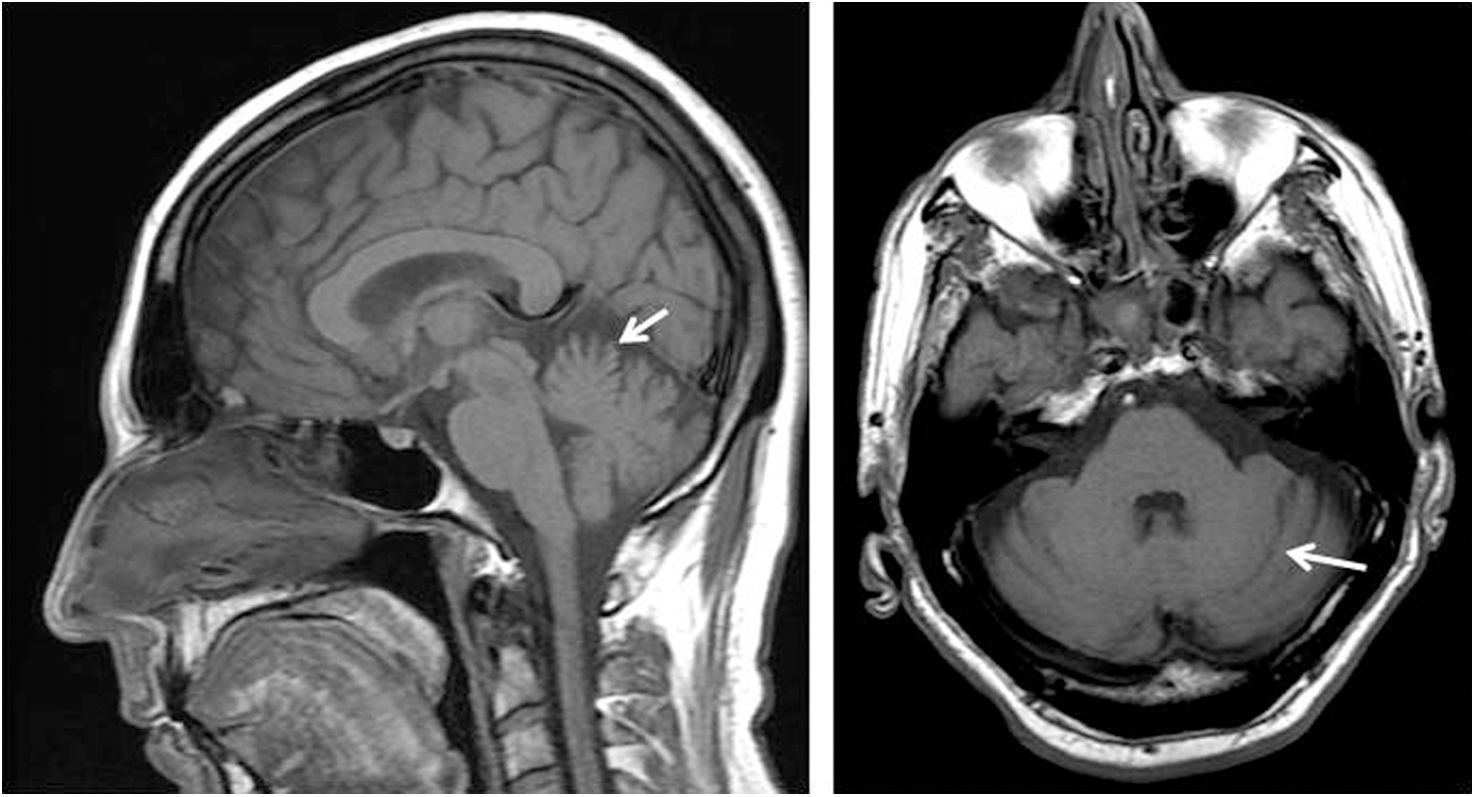

Brain MRI, performed before starting AP treatment, showed vermian atrophy involving mainly the superior part in all patients. There was also slight atrophy of the cerebellar hemispheres in 4 patients (Fig. 1).

A positive family history in first-degree relatives was found in 5 cases. Two of the patients included in our study were siblings (patients 3 and 4).

The father, sister, and uncle of patient 2 suffered from ataxia and relied on wheelchairs 10–15 years after the onset of the disease. This patient, who developed ataxia at 71 years of age, was able to discontinue using a cane after initiating treatment with 4-AP, and continues to walk independently to this day.

On the other hand, the 2 siblings included in our cohort were phenotypically different with regard to clinical symptoms and disease severity. Patient 3 suffered from daily paroxysmal episodes of moderate-to-severe gait instability with dysarthria, blurred vision, and dizziness lasting from 30min to several hours, whereas his sister (patient 4) presented milder symptoms, with slight fluctuations during the day or between days, but without sudden, unexpected, disabling episodes of worsening.

Genetic assessmentGenetic study results were negative for SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, DRPLA, and Friedreich ataxia. Patient 2 carried a heterozygous GAA expansion in the FXN gene. Whole exome sequencing (WES), performed in 5 patients with a positive family history, did not identify pathogenic variants in 350 genes associated with hereditary ataxia.

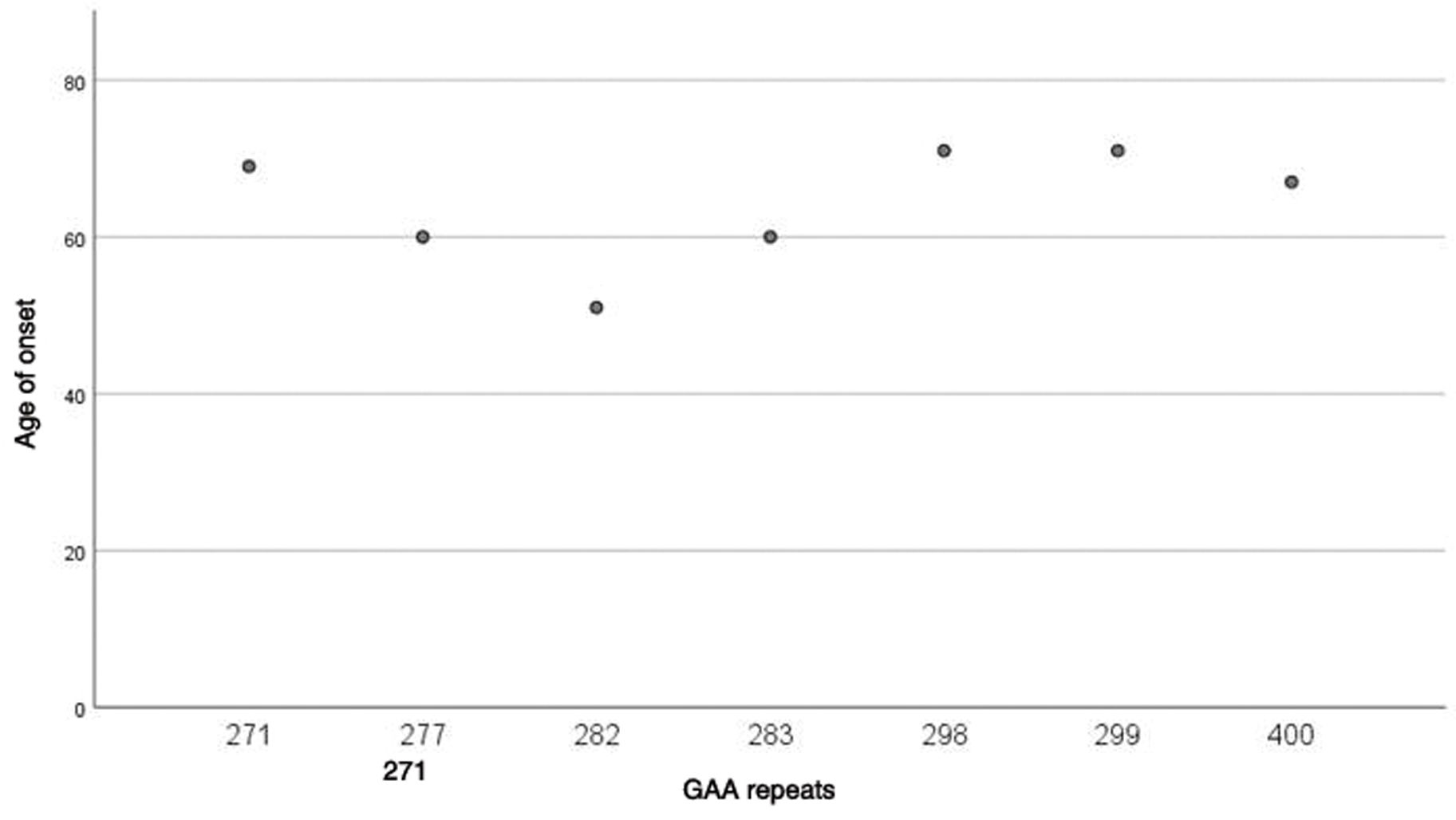

Finally, the study of the intronic GAA expansion in the FGF14 gene showed the presence of an expanded allele in the likely pathogenic (250–300 repeat units) or pathogenic (> 300 repeat units) range in all patients. The size of the repeat expansion varied from 271 to 400 GAA repeats. Median GAA repeat was 290.5 (280.75–309). No correlation was found between the number of GAA repeats and the age at onset of the disease (P=.420) (Fig. 2).

TreatmentBefore starting AP treatment, 6 patients were treated with acetazolamide (500–750mg/day). Treatment was ineffective in 5 patients. A partial, incomplete response was obtained in one patient only. Two patients presented adverse events: one complained of gastric intolerance with nausea and the other reported that clinical fluctuations worsened with treatment.

Compassionate treatment with AP was requested and approved by our local health authorities. Seven patients were under treatment with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) and one with 3,4-diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP). Five patients were treated with the sustained-release form of 4-AP (fampridine) and the other 2 with the immediate-release 4-AP as a compounded medication. Median treatment duration was 43 (14.25–137.25) months. The total dose of 4-AP varied from 15mg/day (compounded medication, 5mg 3 times a day) to 20mg/day (fampridine, 10mg twice a day). The total dose of 3,4-DAP was 20mg/day (3 times a day).

All patients reported improvement of gait instability and visual symptoms after initiating AP, as well as a sustained decrease in the frequency and severity of clinical fluctuations. AP treatment abolished the disabling paroxysmal episodes in patient 3 and markedly improved them in patient 7, so that daily episodes became occasional and were only associated with mild disability in this patient. The median CGI-p was 6.5 (6–8). However, we did not find significant differences between the SARA score before treatment (median: 4 [3.75–5.25]) and the final SARA score (median: 4.25 [4–4.75]) (P=.348). Interestingly, SARA score at baseline and at the last assessment showed mainly axial disturbances involving gait, standing, and lower-limb coordination. Only one patient (patient 6) showed mild dysarthria and upper limb incoordination on examination. Prospective assessment could not be performed for this patient because he presented a lymphoma, which had been diagnosed 2 years before initiating treatment with 4-AP, and he died after a disease relapse. In this case, we compared the SARA score from the last clinical record before his death with SARA score at baseline.

It should be noted that withdrawal of AP treatment in 2 patients (patients 5 and 6) led to marked worsening of the ataxic symptoms and clinical fluctuations, prompting reintroduction of treatment after a few days.

At the time of the last assessment, DBN on primary and downward gaze had practically disappeared in all patients. DBN on lateral gaze persisted, although its amplitude had decreased. In fact, only 2 patients under treatment reported ongoing visual symptoms (blurred vision) during episodes of worsening (patients 2 and 7), although the severity of these symptoms improved with treatment, as the patients reported.

Overall, treatment with AP was well tolerated. Only one patient complained of gastric upset and nausea after increasing the dose of immediate-release 4-AP from 5mg to 10mg in the morning. This adverse event was resolved after reducing the morning dose back to 5mg.

DiscussionIn this ambispective study, we report the demographic, clinical, radiological, and genetic features of a cohort of patients diagnosed with GAA-FGF14 ataxia, as well as their long-term response to AP treatment. All of them were under compassionate treatment with AP prior to the discovery of GAA-FGF14 ataxia. To our knowledge, this is the longest reported duration for an AP study in patients with ataxia associated with DBN.

Our patients presented late-onset disease, starting after the fifth decade of life. Clinical and radiological findings are consistent with those described in larger series of patients.6,7,20 The main symptoms in our patients were gait instability and blurred vision. Slight diplopia was also reported by 3 patients. Clinical fluctuations were present in all patients. Two patients presented sudden, disabling attacks associated with vertigo and dysarthria resembling episodic ataxia type 2. Neurological examination between episodes of worsening of the ataxic and visual symptoms showed the presence of a cerebellar syndrome that predominantly involved gait, stance, and lower limb coordination, as well as the presence of DBN, which predominated on lateral gaze. MRI showed the presence of cerebellar atrophy, mainly involving the vermis, thus explaining the predominance of axial involvement in these patients.

Family history was compatible with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance in most patients, but 3 cases were considered to be sporadic. Genetic studies ruled out presence of the CAG repeat expansions responsible for the common polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias, and WES did not identify pathogenic variants. However, genotyping of the intronic FGF14 repeat locus disclosed the presence of a GAA expansion in the likely pathogenic (250–300 repeat units) or pathogenic range (>300 repeat units) in all patients.6,22 Although our series includes a small number of patients, we did not find a correlation between the number of GAA repeats and age at onset of the disease. In a recent study that included 82 patients carrying an FGF14 (GAA)≥250, only a weak inverse association between age of onset and the size of the repeat expansion was reported.8 This suggests that other currently unknown factors, other than the GAA expansion size, may play a role in modulating disease onset.

In contrast to the response observed in patients with episodic ataxia type 2,23 acetazolamide treatment did not improve either DBN or clinical fluctuations in our patients. In a retrospective study to evaluate the response to acetazolamide in SCA27B ataxia, 19 of 34 patients (56%) showed no benefits from treatment; while subjective improvement was reported in 15 (44%), the response was mild or partial in 6 of these.24 In comparison, our results suggest that long-term treatment with AP is well tolerated and demonstrates sustained efficacy in reducing DBN, fluctuations, and episodic attacks. Patients experienced a median subjective improvement (CGI-p) of 65% in their disability, but in 3 cases the improvement was as great as 80% (Table 2). This improvement was not captured by the SARA score between episodes, which remained without significant changes over time. We believe that this fact is relevant because 3 of our patients have been treated for more than 10 years without showing evidence of disease progression.

A beneficial response to AP treatment in patients with DBN and/or ataxia has been described in recent studies.8,20,21 However, comparison between these studies and our own is difficult for several reasons. In one study,8 the response to treatment was stratified on the basis of FGF14 genotype (GAA expansion≥250, 200–249, or <200 repeats) rather than phenotype. In another study,20 the response to 4-AP with relevance for everyday living was reported in 6 out of 7 patients treated, but treatment duration was not assessed. Finally, in addition to these retrospective cohorts analysis, 2 prospectively structured n-of-1 open-label treatment experiences with 4-AP have been published.20,21 In both studies, during ON periods with 4-AP, patients reported an improvement with reduction in symptomatic time per day and the frequency of days affected by severe symptoms,20 or with a significant change on a 5-point Likert scale.21 These changes were accompanied by a reduction in SARA score20 or by improvement in objective digital-motor measurement.21 In both studies, the beneficial effect of 4-AP disappeared during OFF periods.

Reduced expression of the FGF14 gene leads to a decrease in the spontaneous firing rate and excitability of Purkinje cells.25 4-AP is a dose-dependent reversible blocker of voltage-gated potassium channels.8 Studies of animal models have suggested that 4-AP improves cerebellar locomotor function by regulating Purkinje cell activity.26,27 This effect is mediated by the inhibition of potassium currents, which increases the duration and amplitude of the action potential, thus improving axonal conduction and neurotransmitter release.27 These findings may explain the physiological mechanisms by which patients with GAA-FGF14 ataxia can improve with AP treatment.

Recent studies into disease progression in GAA-FGF14 ataxia have shown that gait ataxia worsens slowly,8,20 with half of subjects requiring aids for walking by 8 years after disease onset.20 Upper limb incoordination, afferent sensory deficits and urinary dysfunction also become frequent as the disease progresses.20 The stability of the SARA score in our patients after many years of treatment, along with the absence of symptoms suggesting extracerebellar involvement, suggest that AP might slow disease progression. While this observation requires validation in a larger randomized controlled trial, it has previously been reported that AP normalizes firing rate and motor behavior in the ataxin-1 mutant mouse and that the animals treated early displayed better motor function in the longer term, which may be mediated by a neuroprotective effect due to enhanced electrical activity of Purkinje cells.28,29

The main limitations of our study are the small number of patients included, the open-label real-world treatment response data assessment with no control group, the heterogeneity of study drugs, and the retrospective approach, many years after onset of AP treatment. This fact may have made it difficult for the patients to compare their disability before starting treatment with the current disability. In addition, the lack of quality-of-life assessment and quantitative studies of DBN, gait, and posture, other than SARA score, precludes us from having more quantifiable data supporting the long-term efficacy of AP in patients with ataxia associated with DBN. However, we believe the main strength of our study is the relatively long duration of treatment for all patients and the fact that none of them discontinued the medication after many years of follow-up, reinforcing its good tolerability and the benefits seen by these patients.

ConclusionLong-term treatment with AP (15–20mg/day) is well tolerated and effective in patients with ataxia associated with DBN due to the intronic GAA expansion in the FGF14 gene. Prospective randomized trials are needed in order to better evaluate the impact of AP treatment on disease progression.

Author contributionsEsteban Muñoz: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing – original draft preparation (lead), writing – review and editing (lead).

Myriam De la Puebla-Puebla: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing.

David Pellerin: Investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing.

Cèlia Painous: Formal analysis, methodology, writing – review.

Maria Isabel Álvarez-Mora: Investigation, writing – review.

Maria-Josée Dicaire: Investigation, writing – review.

Laia Rodriguez-Revenga: Investigation, writing – review.

Matt C. Danzi: Investigation, writing – review.

Stephan Zuchner: Funding acquisition, investigation, writing – review.

Bernard Brais: Funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing – review.

Ethical standardsThe study was approved by the medications research ethics committee of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB/2022/0672). The study was carried out with the understanding and written consent of the participants, and in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, and Spanish Royal Decree 957/2020, of 3 November, which regulates observational studies with medications in humans in Spain.

Sources of fundingThe genetic study of the patients was supported by the Monaco Group Foundation; a grant (496100) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); and a grant (2R01NS072248-11A1, to Dr. Zuchner) from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Pellerin holds a Fellowship award from the CIHR.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.