To analyze the effectiveness of intrathecal baclofen in the treatment of spasticity of different aetiologies in the upper limbs, lower limbs, and both children and adults.

DesignMeta-analysis.

Subjects/PatientsPeople with spasticity of different aetiologies in treatment with intrathecal baclofen.

MethodsA systematic search was performed in the PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases with the earliest data available up to November 1, 2022. Random-effects models were used to calculate pooled mean difference estimates and their respective 95% CIs to assess the effectiveness of intrathecal baclofen treatment on spasticity of different aetiologies using the modified Ashworth scale. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA 15 software.

ResultsFinally, 11 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The effect of baclofen treatment administered by an intrathecal pump on spasticity measured by the modified Ashworth scale led to a significant decrease in spasticity in both adults (MD: −1.54; 95% CI: −1.80, −1.27) and children (MD: −0.70; 95% CI: −0.91, −0.49), with greater effectiveness for lower limb spasticity (MD: −1.45; 95% CI: −1.93, −0.97). The results should be interpreted with caution since there is heterogeneity due to differences between populations (age or types of diseases).

ConclusionThese findings are important for clinical practice, as they demonstrate the efficacy of intrathecal baclofen in treatment of spasticity, thus improving patient quality of life, being more effective at a younger age and longer duration of treatment, always taking into account statistical limitations.

Analizar la eficacia del baclofeno intratecal en el tratamiento de la espasticidad de diferentes etiologías en miembros superiores, miembros inferiores y ambos, en niños y adultos.

DiseñoMetaanálisis.

Sujetos/PacientesPersonas con espasticidad de diferentes etiologías en tratamiento con baclofeno intratecal.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda sistemática en las bases de datos PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library y Web of Science con los primeros datos disponibles hasta el 1 de noviembre de 2022. Se utilizaron modelos de efectos aleatorios para calcular las estimaciones de diferencia de medias agrupadas y sus respectivos IC 95% para evaluar la efectividad del tratamiento con baclofeno intratecal sobre la espasticidad de diferentes etiologías utilizando la escala de Ashworth modificada. Todos los análisis estadísticos se realizaron con el programa STATA 15.

ResultadosFinalmente, se incluyeron 11 estudios en el metaanálisis. El efecto del tratamiento con baclofeno administrado mediante una bomba intratecal sobre la espasticidad medida mediante la escala de Ashworth modificada muestra una disminución significativa de la espasticidad tanto en adultos (DM: -1.54; IC 95%: -1,80, -1,27) como en niños (DM: -0,70; IC 95%: -0,91, -0,49), con mayor efectividad en la espasticidad de miembros inferiores (DM: -1,45; IC 95%: -1,93, -0,97). Los resultados deben interpretarse con cautela, ya que existe heterogeneidad debida a diferencias entre poblaciones (edad o tipos de enfermedades).

ConclusionesEstos hallazgos son importantes para la práctica clínica, ya que demuestran la eficacia del baclofeno intratecal en el tratamiento de la espasticidad, mejorando así la calidad de vida del paciente, siendo más eficaz a menor edad y mayor duración del tratamiento, siempre teniendo en cuenta las limitaciones estadísticas.

Spasticity was defined by Lance in 1980 as “an intrinsic increase in the speed-dependent muscle resistance of the tonic stretch reflex to passive movement of a limb in people with upper motor neuron syndrome”,1–3 which was later defined as “a disorder of sensory and motor neuron injury, presenting with involuntary and sustained muscle activation”.1 In 2016, an international initiative introduced aspects of functional impact into the definition, considering spasticity as a limitation of body functions, activities and participation.3 Spasticity causes problems such as developmental disorders in childhood, impaired functional capacity, abnormal postures that can cause pain, and aesthetic and hygienic alterations.4 Therefore, it has a great impact on the individual's life due to loss of autonomy and functionality and reduced quality of life.3 Spasticity can arise from different aetiologies. It can be classified according to its aetiology as supraspinal, such as stroke or cerebral palsy (CP), and spinal or mixed, such as multiple sclerosis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.3 CP is a disorder of body movement and posture that arises as a result of a nonprogressive lesion in the developing brain.2 Its prevalence in Spain, depending on the cause, is as follows: in patients who have had a stroke, 20%; in subjects with moderate-severe cranioencephalic trauma, 13–20%; in patients with spinal cord injuries, 60–78%; in patients with multiple sclerosis, 84%; and in patients with infantile CP, 70–80%. In summary, 10 out of every 1000 subjects live with this health problem in our country. It is important to keep in mind that untreated spasticity increases medical costs in all aspects of health.4

Different scales can be used for assessment of spasticity, such as the Tardieu Scale,1,3 the Triple Spasticity Scale, the Spinal Cord Assessment Tool for Spastic Reflexes,3 the Gross Motor Function,2 the Oswestry Scale, the Global Functional Disability Scale of the University of Lyon, the Paediatric Disability Assessment Inventory and the Barry-Albright Dystonia Scale.1 The most widely used is the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS),1,3 which assesses the degree of increased muscle tone of the affected limb on a 5-point scale,2 although it is not sensitive to distinguish it from other muscle tone disorders.3 Treatment of spasticity requires a multidisciplinary team1,3 consisting of physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, orthopaedic technicians and nurses.3 The different treatments include health education on spasticity; physiotherapy; transcutaneous electrical stimulation; use of orthoses; chemo-denervation and neurolysis therapies (botulinum toxin type A and B, phenol and ethyl alcohol); pharmacological therapy (baclofen, dantrolene and tizanidine, benzodiazepines, serotonergic agonists, potassium channel blockers, cannabinoids, intrathecal baclofen [ITB]); and surgical treatment (tendon lengthening or transposition and selective dorsal rhizotomy).1,3,4 In patients with severe spasticity (MAS score above 3 points), ITB administration is indicated, achieving therapeutic effects at very low doses and avoiding systemic side effects.1,3,4 This treatment is performed by implantation of a subcutaneous programmable infusion pump.1,2,4

There are several previously published systematic reviews assessing ITB treatment and concluding that ITB therapy reduces spasticity and facilitates care, with insufficient evidence for improvement in quality of life.2,5–7 Furthermore, a current study shows that ITB therapy is difficult to maintain in the long term.7 A meta-analysis published in 2021 argues that ITB therapy improves spasticity, pain, and quality of life and facilitates care but has no effect on motor function.8 Although there is evidence for the efficacy of ITB in treatment of spasticity, it seems necessary to evaluate whether this therapy is effective for spasticity of different aetiologies. Therefore, the aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to analyze the efficacy of ITB in treatment of upper limb (UL) spasticity, lower limb (LL) spasticity and both and to analyze the efficacy of ITB in treating spasticity of different aetiologies in both children and adults.

MethodsThis systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines9 and was performed following the recommendations of Cochrane Collaboration Handbook.10 It was realized from the earliest data available until November 1, 2022. This study was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42022371818).

Search strategyFor this systematic review and meta-analysis, a search strategy was conducted using the PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, and Web of Science databases from the earliest data available until November 1, 2022. The following terms were used to perform the search: “general population”, “children”, “adults”, “intrathecal baclofen”, “cerebral palsy”, “spasticity”, “spastic paraplegia”, “clinical trials”, and “trials”, combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR) following the PICO strategy (population, intervention, comparator, outcome), to identify primary articles studying ITB in the treatment of spasticity (Supplementary Table 1).

In addition, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as reference lists of retrieved articles, were examined to identify any other relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaStudies on the effectiveness of ITB in treatment of spasticity were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) Population: subjects (both children and adults) with spasticity; (ii) Intervention: treatment with ITB; and (iii) Outcome: spasticity assessed with the MAS scale. We excluded (i) articles that were not written in English or Spanish; (ii) review articles, editorials or case reports; and (iii) study designs that were not clinical trials.

Data extractionAn ad hoc table was used, and the following data were extracted from the included studies: (i) reference (first author and year of publication), (ii) country in which study data were collected, (iii) study design (quasiexperimental and clinical trials), (iv) population characteristics (sample size, mean age and type of population), (v) intervention characteristics (length, baclofen dose and pump insertion site), and (vi) outcome (measurement method and mean MAS scale reduction value).

Quality assessmentThe quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB2).11 This tool assesses the risk of bias based on five domains: randomization process, deviations from interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement and selection of the reported outcome. Overall bias was rated as “low risk of bias” when all domains were classified as “low risk”, “some concerns” when there was at least one domain classified as “high risk” or several domains classified as “some concerns”. Two researchers independently performed the study selection, data extraction and assessment of the methodological quality of the included clinical trials. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

Statistical analysisThe DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method12 was used to calculate pooled estimates of mean differences (MD) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to analyze the effect of ITB on spasticity according to UL, LL or both. Heterogeneity was examined using the I2 statistic,13 which ranged from 0% to 100%. According to I2 values, heterogeneity was considered not important (0–30%), moderate (30–60%), substantial (60–75%) or considerable (75–100%). Corresponding p values were also considered.

Sensitivity analysis (systematic reanalysis removing studies one at a time) was performed to assess the robustness of the summary estimates. Subgroup analysis was performed according to population type (children and adults). In addition, meta-regression analyses were performed according to mean age, dose, age*dosage and length of treatment to analyze whether the effect of ITB treatment on spasticity was modified. Finally, publication bias was assessed using Egger's regression asymmetry test.12 A level of <0.1 was used to determine whether publication bias was present.

All statistical analyses were performed with STATA SE software, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

ResultsBaseline characteristicsForty-nine records were selected for the full-text review after screening by title and abstract. Twenty-seven studies were included in the systematic review,13–39 and eleven studies were included in the meta-analysis13,17,20,22,23,28,29,33,35,36,38 (Fig. 1).

The studies included in this systematic review were published between 1992 and 2018, of which 23 studies were quasiexperimental15–38 and 3 were randomized clinical trials.39–41 The sample size ranged from 2 to 102 subjects, and the age of subjects ranged from 2.5 to 75 years. Study participants had spasticity caused by different diseases, such as CP,19,22,23,26,27,30–34,37,38 paraplegia,15,20,29,35,39 spasticity of cerebral origin,16,24,25,28,40 hypoxic brain injury21,41 and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.31 The duration of the studies was between 3 and 108 months. The minimum dose was 25 micrograms/day, and the maximum dose was 900 micrograms/day. Most studies did not report pump location; those that did reported pump location in the thoracic,19,22,27,31–33,37,40 lumbar,31,37 or cervical32 region. All included studies assessed spasticity with the MAS scale, from which the mean reduction value was extracted. All characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| References | Country | Study design | Population characteristics | Intervention characteristics | Outcome: spasticity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n (% female) | Mean age (years) | Population characteristics | Length (months) | Baclofen dose (μg/day) | Pump insertion location | Location of spasticity | Average downscaling value | |||

| Meytaler JM et al. (1992) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 3 (0%) | 46–62 | CP | 3 | 100 | Lumbar region | LL | 1.92±0.58 |

| Armstrong RW et al. (1997) | Canada | Quasiexperimental | 19 (NR) | 4–19 | NR | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Becker R et al. (1997) | Germany | Quasiexperimental | 18 (27.78%) | 2.5–70 | NR | 13–54 | 100–600 | NR | Both limbs | 2.33 |

| Rawicki B. (1999) | Australia | Quasiexperimental | 18 (NR) | 13–57 | NR | 12–108 | 80–900 | NR | NR | 3 |

| Gilmartin R et al. (2000) | USA | Multicentre RCT | 51(43.14%) | 4–31.3 | Paraplegia | 43 | 402.1 | NR | Both limbs | 2.14 |

| Van Schaeybroeck P et al. (2000) | Belgium | Controlled RCT | 11 (NR) | 8–55 | NR | 24 | 50–200 | T10 | NR | Decreases with respect to baseline values |

| Scheinberg AM et al. (2001) | Australia | Quasiexperimental | 2 (NR) | 8–9 | CP | 6 | 150–225 | T10 | NR | MAS: is reduced |

| Murphy NA et al. (2002) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 23 (26.09%) | 4.5–17.4 | Paraplegia | 48 | NR | NR | Both limbs | LL: 2.43±0.73UL: 2.07±0.65 |

| Sgouros S and Seri S. (2002) | United Kingdom | Quasiexperimental | 6 (33.33%) | 9–17 | NR | 24 | 50–100 | NR | NR | NR |

| Albright AL et al. (2003) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 68 (NR) | 12–16 | CP | 70 | 153–300 | T4; T6-9 y T10-12 | Both limbs | NR |

| Awaad Y et al. (2003) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 55 (54.29%) | 4–32 | CP | 24 | 163–544 | NR | Both limbs | 1.61±0.58 |

| Albright AL et al. (2004) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 102 (33.33%) | 1.4–16.8 | NR | 12 | NR | NR | NR | 0.75±0.85 |

| Fares Y et al. (2004) | Spain | Quasiexperimental | 23 (39.13%) | 39 | NR | 52 | 91.96–137.81 | NR | NR | 2.04 |

| Krach LE et al. (2004) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 33 (39.40%) | 4–31 | CP | 12 | 256.2 | NR | LL | 2.17 |

| Krach LE et al. (2005) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 31 (38.71%) | 4–29.5 | CP | 12 | 241.7 | 84% between T10-T12 | LL | ≥2.0 |

| Bensmail D et al. (2006) | France | Quasiexperimental | 20 (25%) | 45±13 | NR | 24 | NR | NR | NR | 1.15±0.36 |

| Bleyenheuft C et al. (2007) | Belgium | Quasiexperimental | 7 (71.42%) | 18.4±7 | Paraplegia | 14.4 | 110.6 | NR | LL | 1 |

| Brochard S et al. (2009) | France | Quasiexperimental | 21 (66.67%) | 11.3±4.8 | CP | 25.8 | 174.3 | NR | LL | 1.8 |

| Hoving MA et al. (2009) | Netherlands | Quasi prospective | 17 (52.94%) | 13.7±2.9 | CP | 12 | 233 | 57% at thoracic level and 43% at lumbar level | NR | Significant decrease in MAS in 5/8 of de UL muscle groups and in 9/14 of the LL muscle groups |

| Ward A et al. (2009) | Australia | Quasiexperimental | 25 (60%) | 10 years and 3 month | CP | 96 | NR | L2-3; C1-7; T2-6 | LL | 1.43 |

| Ponche ST et al. (2010) | France | Quasiexperimental | 25 (44%) | 29.6±12.7 | CP | 55.2 | 292 | 32% in the mid-thorax, 20% in the upper thorax and 20% in the toracolumbar region | NR | 2±0.06 |

| Morton RE et al. (2011) | United Kingdom | Quasiexperimental | 38 (47.37%) | 10.2±3.1 | CP | 18 | 216 | NR | NR | NR |

| Margetis K et al. (2014) | Greece | Quasiexperimental | 16 (37.5%) | 20–68 | Paraplegia | 25.8 | 90 | NR | LL | 0.7±0.9 |

| Hidalgo ET et al. (2017) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 2 (50%) | 2 y 19 | NR | 27 | 25–215 | NR | Both limbs | NR |

| Kraus T et al. (2017) | Austria | Quasiexperimental | 13 (23.08%) | 13.9 | CP | 60 | NR | T7 (n=4), T8 (n=7), L1 (n=1), L3 (n=1) | Both limbs | 1.7 |

| Yoon YK et al. (2017) | USA | Quasiexperimental | 37 (18.92%) | 36±2.7 | CP | 12 | NR | NR | Both limbs | UL: 2.2±0.2LL: 2.2±0.2 |

| Creamer M et al. (2018) | USA | Controlled RCT | 60 (30%) | 18–75 | NR | 6 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Data are shown as the mean±standard deviation (SD) or interquartile range. CP (cerebral palsy); LL (lower limbs); MAS (Escala de Ashworth Modificada); NR (not reported); RCT (randomized clinical trial); UL (upper limbs).

The Cochrane Collaboration tool (RoB2) was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies.11 Most of the studies had a “high risk of bias” (92.59%), and only two of them were assessed as “some concerns” (7.41%). “High risk of bias” was present in the domains of randomization (88.88%) and selection of the reported outcome (81.48%). In the domain of deviations from interventions, the outcome of most studies was “some concerns” (81.48%), and in the domains of missing outcome data (100%) and measurement, the outcome (92.59%) was “low risk of bias” (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

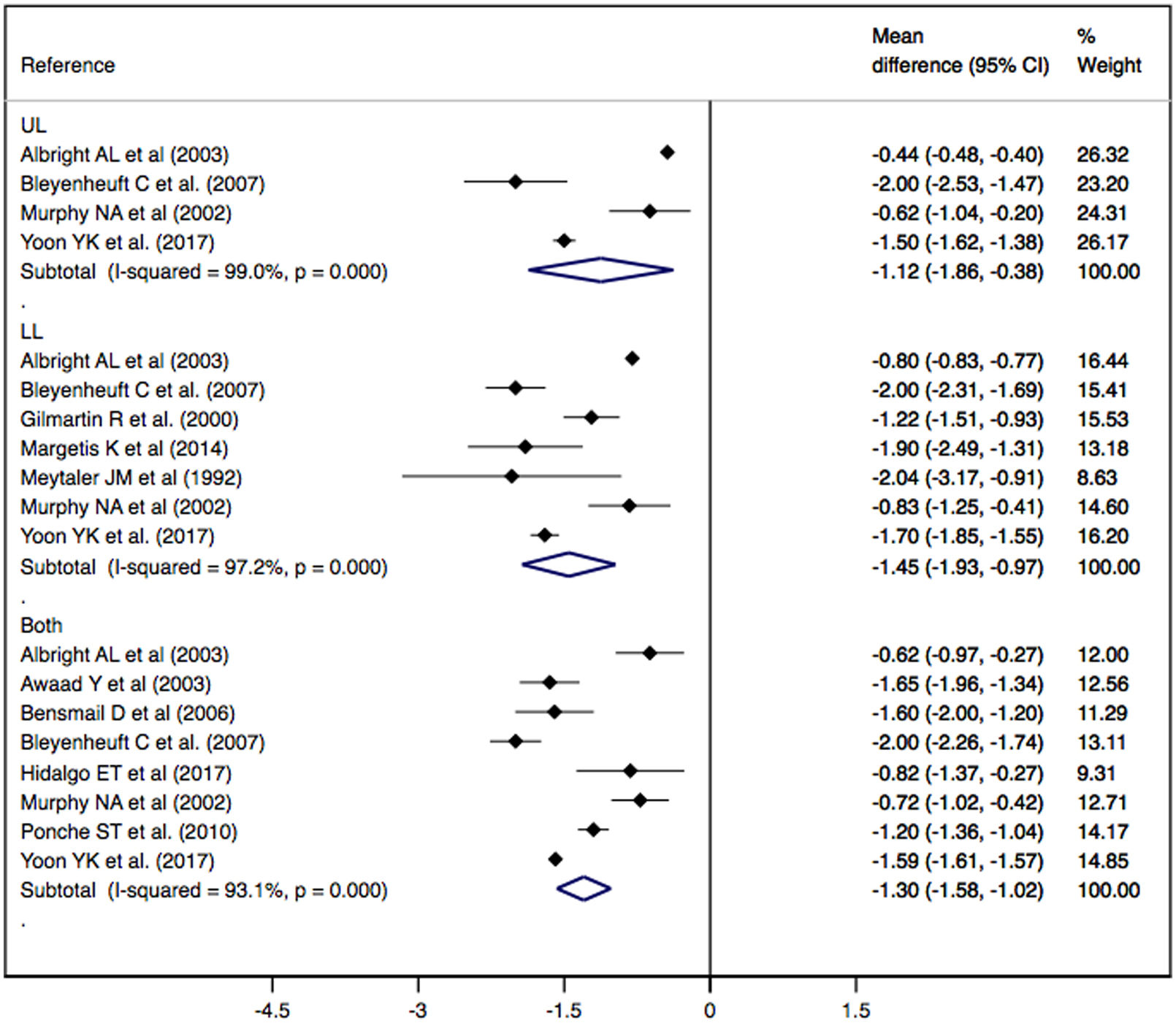

Effect of ITB therapy on spasticityThe effect of ITB therapy administered by an infusion pump on spasticity measured by the MAS scale showed a significant decrease in spasticity in UL (MD: −1.12; 95% CI: −1.86, −0.38), LL (MD: −1.45; 95% CI: −1.93, −0.97) and both (DM: −1.30; CI 95%: −1.58, −1.02), showing substantial heterogeneity in all cases (I2=99.0%, p=0.000; I2=97.2%, p=0.000; I2=93.1%, p=0.000, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Sensitivity analysisThe pooled MD estimate for the effect of ITB on spasticity was not significantly modified (in magnitude or direction) when data from individual studies were removed one study at a time from the analysis.

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression modelsSubgroup analysis according to population type (adults and children) showed a significant decrease in spasticity on the MAS scale in subjects with CP (MD: −1.30; CI 95%: −1.61, −1.00) and in subjects with paraplegia (MD: −1.42; CI 95%: −1.90, −0.95), showing substantial heterogeneity in both groups (I2=91.7%, p=0.000; I2=83.8%, p=0.000, respectively) (Supplementary Table 2).

Meta-regression models according to mean age, dose and length of treatment showed that both mean age (p=0.028), length (p=0.003) and age*dosage (p=0.050) could modify the effect of ITB on spasticity (Supplementary Table 3).

Publication biasFinally, evidence of publication bias was found using Egger's test for the effect of intrathecal baclofen on LL spasticity (p=0.073) (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the effect on UL spasticity (p=0.392) (Supplementary Fig. 4) and for the effect on both LL and UL spasticity (p=0.752) (Supplementary Fig. 5), no publication bias was found.

DiscussionA previous systematic review and meta-analysis reported that ITB treatment can improve dystonia, pain and comfort and facilitate care, thus improving patient quality of life but having little or no effect on motor function.8 Our findings support previous evidence on the efficacy of ITB in spasticity, showing this effect in UL, LL and both, with a greater effect when the length of treatment is longer and in younger subjects. In addition, patient age and length of treatment were found to be moderators of the effect of ITB on spasticity. Duration had a direct relationship with the effect of baclofen, i.e., a longer treatment duration implies a greater effect, and age and age*dosage interaction have an indirect relationship, i.e., younger age leads to a greater effect.

This treatment is performed by means of an intrathecal release of baclofen, which produces neuromodulation. The infusion pump is programmable and is placed subcutaneously in the abdomen. Compared to oral administration, intrathecal administration is associated with greater efficacy in controlling spasticity and less patient sedation.1 According to previous evidence, the best candidates for ITB therapy are people with moderate or severe spasticity in LL who have responded well to ITB bolus.39,40 Moreover, a study in patients with CP and dystonia reported a significant reduction in spasticity on the MAS scale in LL and a smaller reduction in UL.32 In addition, a clinical trial reported that in ambulatory patients, inserting the catheter at a higher level improves the effect on UL without weakening the legs.40

According to our findings, ITB treatment is more effective in younger patients. In line with these results, a clinical trial corroborates that ITB would allow younger patients to optimally develop motor skills during childhood before the learning process is hindered by spasticity.40 Another study shows that younger patients (<18 years) have a greater reduction on the MAS scale than adult patients (>18 years),23 although our results show that it is effective in both children and adults. In addition, a longer length of ITB treatment implies greater efficacy, possibly due to the process of adaptation and tolerability of each patient until the appropriate dose is achieved.42

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as most of the included studies were prepost studies with no control group, the data will not be extrapolable to the general population, although three clinical trials were included that showed that ITB therapy is effective in reducing spasticity.39–41 Second, since there was heterogeneity due to differences between populations (age or types of diseases), the results should be interpreted with caution, although subgroup analyses and meta-regressions were performed to mitigate heterogeneity. Third, the sample sizes were small because the prevalence of spasticity diseases is low, making it difficult to find subjects on ITB therapy. Fourth, ITB therapy is dose dependent, and there are differences in the doses administered in the included studies and between patients. Fifth, only the MAS scale was included to assess spasticity, which is self-reported; thus, there may be a reporting bias. Sixth, there is little evidence available assessing the efficacy of ITB in children and adults. Seventh, the overall risk of bias for RCTs showed a high risk of bias in most studies. Eighth, there was evidence of publication bias by Egger's test, and unpublished results could modify the findings of this meta-analysis. Therefore, high-quality RCTs are needed to test the efficacy of ITB in different populations (children and adults) with different characteristics for the improvement of spasticity.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that ITB is effective in reducing spasticity in both LL and UL regions and is more effective in LL. This treatment is effective in spasticity of different aetiologies and shows that ITB has a greater effect the longer the duration of treatment is and younger the age of the patient is. The age*dose relationship shows an indirect relationship in terms of the effect of the ITB. These findings are important for clinical practice, as they show evidence that ITB is effective in reducing spasticity and is beneficial in improving both the patient's quality of life and that of their environment. However, controlled clinical trials with a larger sample size are needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of ITB and to generalize its use in daily clinical practice.

FundingThis research was funded by the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha and co-funded by the European Union (ERDF/ESF), grant number 2023-GRIN-34459. C.P.-M. is supported by a grant from the University of Castilla-La Mancha (2018-CPUCLM-7939). I.M.-G. is supported by a Grant from the science, innovation and universities (FPU21/06866). S.N.A.-A. is supported by a grant from the University of Castilla-La Mancha (2020-PREDUCLM-16704).

ContributorsConceptualization, I.O.-L., A.S.-L., and I.C.-R.; Methodology, I.O.-L., S.N.A.-A., and I.C.-R.; Software, I.C.-R and S.N.A.-A.; Validation, A.S.-L. and I.M.-G.; Formal analysis, I.O.-L. and S.N.A.-A.; Investigation, I.O.-L. and I.C.-R.; Resources, I.O.-L., A.S.-L., and I.M.-G.; Data curation, I.C.-R. and C.P.-M.; Writing—original draft preparation, I.O.-L. and I.C.-R.; Writing—review & editing, C.P.-M.; Visualization, A.S.-L. and I.M.-G.; Supervision, I.C.-R. All of the authors revised and approved the final version of the article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.