Spontaneous hypotension is an infrequent, potentially fatal condition, usually related to a Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) leak producing intracranial hypotension (ICH), leading to a downward displacement of the brain known as “brain sag”.1

Brain sagging syndrome (BSS) has recently been described2,3 as clinically indistinguishable from behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (Bv-FTD) but with neuroimaging findings suggestive of ICH,3 and a potentially reversible course.

We report a 53-year-old male, without relevant medical history, who developed progressive bilateral tinnitus and orthostatic headache for six months, and later on: recurrent falls, behavioral changes (irritability, disinhibition, being socially inappropriate), delusional ideation and insomnia, progressively worsening over two months, requiring hospital admission.

On examination, relevant findings were cerebellar syndrome (four-limb dysmetria, gait ataxia with retropulsion, Video-A), kinetic tremor and severe cognitive decline (evaluated with Trail Making Test, Frontal Assessment Battery, Boston Naming Test, Complex Figure of Rey, etc.), consisting in dysexecutive frontal syndrome, severe behavioral impairment with apathy and impulsivity. Blood test resulted normal. CSF study showed low opening pressure (4cm H2O), without other alterations. Cranial-CT scan showed bilateral subdural hygromas. During hospital admission clinical condition worsens, presenting urinary incontinence, inability to walk, and severe behavioral impairment (quetiapine 50mg is started with partial response), being dependent for all activities.

Given the rapidly progressive dementia and ataxia, we proposed the following differential diagnosis: Vascular etiology was ruled out given the progressive course and absence of focal symptoms. The patient did not fulfill 2018 diagnostic criteria for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease given the absence of cardinal symptoms or radiological findings. Other neurodegenerative diseases were unlikely given the aggressive course and lack of typical radiological findings. Negative serologies (HIV, Whipple) and lack of fever ruled out infectious cause. Autoimmune etiology was also ruled out given the normal blood analysis (including onconeural antibodies) and absence of systemic manifestations.

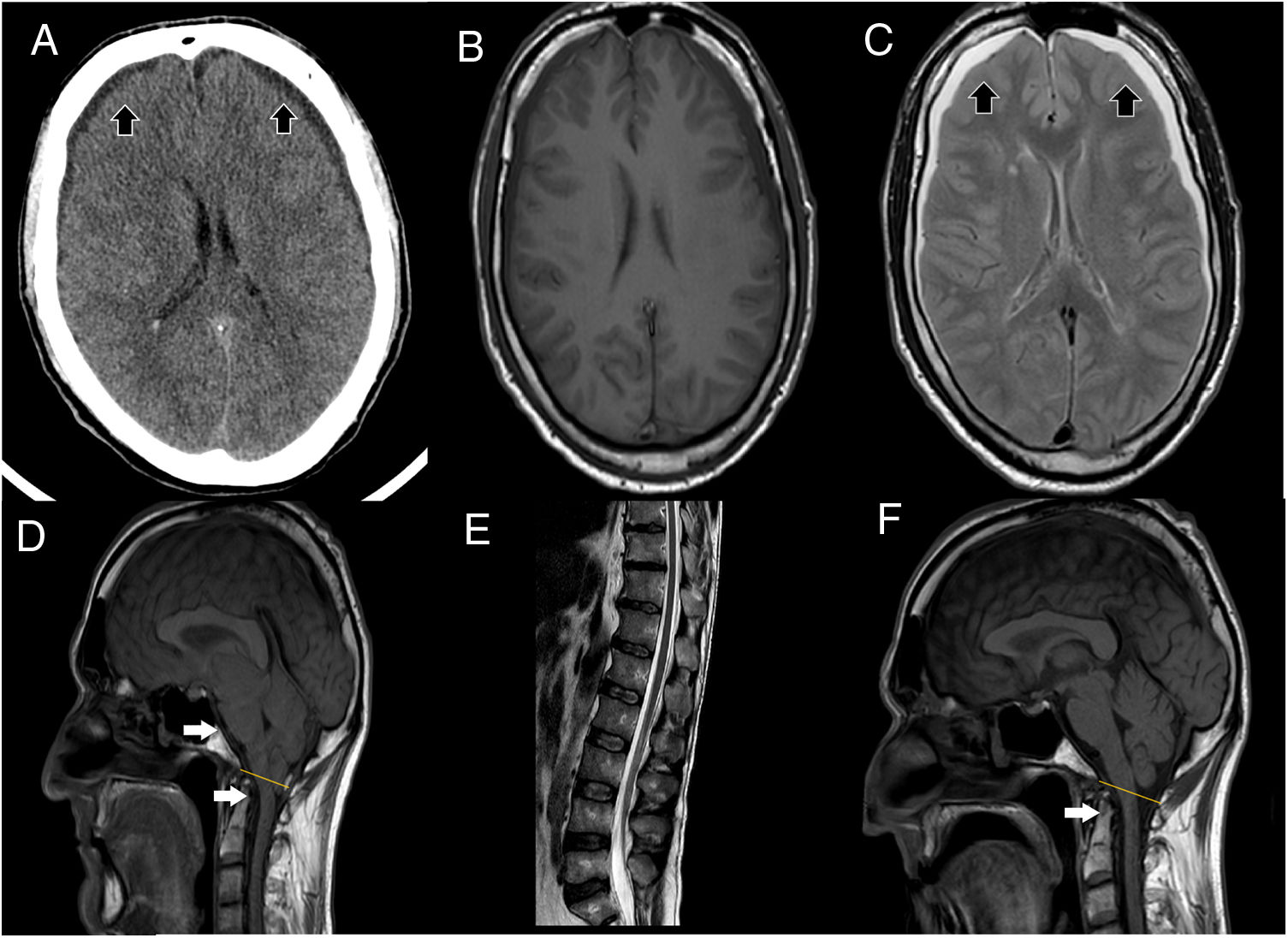

Brain MRI showed descent of the cerebellar tonsils, trans-tentorial herniation, distortion of the brainstem structures and descent of the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1), findings suggestive of ICH. Spinal MRI demonstrated descent of the spinal cord, cisternography showed CSF leak point at D5 level.

(A) Cranial CT scan shows bilateral subdural collections (as the black arrows point), without associated mass-effect, suggestive of subdural hygromas. (B, C) It stands out collapsed lateral ventricles, also bilateral subdural collections, hypointense in T1 (B), hyperintense in T2 (C) sequences (as the black arrows point), without enhancement after contrast administration, supporting the suspicion of subdural hygromas. (D) T1 weight sagittal sequence showed severe downward displacement of cerebellar tonsils (as the white arrows point) below the McRae line (represented by the yellow line), distortion of the brainstem structures and descent of the splenium of the corpus callosum. (E) Spinal MRI showing inferior and ventral displacement of the medullary cord. (F) Resolution of downward displacement of brainstem (as the white arrows point) and cerebellar structures (cerebellar tonsils are placed above the McRae line, represented by the yellow line). Resolution of the rest of the signs suggestive of brain sagging.

Final diagnosis was rapidly progressive dementia (suggestive of Bv-FTD) and cerebellar ataxia, probably secondary to ICH, an entity described as BSS.

We treated ICH with an epidural blood patch, first lumbar (with transient improvement of gait), and later on at dorsal level, achieving progressive significant improvement, both radiologically (resolution of brain sagging, Fig. 1) and clinically, with resolution of ataxia (improvement of SARA scale from a score of 16–0) and recovery of cognitive-behavioral symptoms. Clinical response was maintained six months after discharge (Video-A).

The classic symptoms of ICH include orthostatic headache, tinnitus4 and, in severe cases, coma and death.1 In 2002,5 Hong et al. reported a patient with ICH symptoms and cognitive deterioration suggestive of Bv-FTD, with neuroimaging signs of ICH, without frontotemporal atrophy. In 2011, Wicklund et al.3 described 8 cases with ICH, similar cognitive impairment and other neurological symptoms such as tremor, chorea, dysphagia and gait disturbance, proposing the term BSS to describe this entity. Since then, different cases1–3 have been reported, confirming the probable link between ICH and BSS. The few pathological studies in BSS diagnosed patients showed absence of typical Bv-FTD pathological findings.3 The descent of the brain structures would exert traction on the frontal–temporal cortex, brain stem, cerebellum and their networks,3 leading to dysfunction and the symptoms described. Why some ICH patients develop BSS remains unexplained, BSS could be an extreme presentation of ICH.

BSS affects predominantly middle-aged males (median 53 year).3 Clinical features (usually with an insidious onset)1 includes dementia (present in almost all cases, Bv-FTD profile),4 cerebellar syndrome (66–75% of cases),3,4 movement disorders3,4 (tremor,1 chorea1,3), sleep disorders,3,4 urinary incontinence,1 ICH classic symptoms (orthostatic headache, tinnitus)4 and death.1

Most authors recommend prioritizing ICH treatment, either with a blood patch (multiple times if needed) or surgery of the CSF leak.4 The most extensive series reported good functional recovery in treated patients (up to 72%).4 Different symptomatic treatments (donepezil, quetiapine) have been tried,1,3,6 with diverse results. More studies are needed to draw more weighty conclusions in this regard.

Our case highlights the importance of suspecting BSS in patients presenting subacute ataxia and dementia, especially with another accompanying neurological symptoms (like movement and sleep disorders). In the case described, it stands out that repetitive epidural blood patches were needed, with a suboptimal response the first time. Neuroimaging studies should be reviewed in detail looking for characteristic BSS findings, as it is a rare but potentially reversible entity, with a fatal course in the absence of treatment.2