Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating disease accompanied by physical and mental comorbidities. Little is known about the relation between different comorbidities and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in people with MS (pwMS). Therefore, we designed this study to assess the association between comorbidities and HRQOL.

MethodsIn this cross-sectional study, of 976 pwMS attending the MS clinic of Kashani Hospital in Isfahan, Iran were assessed. The data on comorbidity were extracted from patients’ medical records. The 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) was used to measure HRQOL. Firstly, the association between each comorbidity and HRQOL was assessed. Then, the comorbidities were categorized into physical, psychiatric, and autoimmune, and the association of each comorbidity group with HRQOL was evaluated.

ResultsThe mean (SD) age and disease duration were 37.58 (9.22) and 7.41 (5.24); most of them were female (82.8%) and had a relapsing course (77.1%). The most common comorbidity was migraine (13.6%), followed by hypothyroidism (13.5%), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) (13.5%), and anemia (11.5%). There was a significant association between the physical component score (PCS) of HRQOL and reduced epilepsy, coronary artery disease, eye diseases, OCD, major depressive disorder (MDD), and borderline personality disorder. Regarding mental component (MCS), ovarian failure, polycystic ovary syndrome, OCD, and MDD had an association with low MCS. After categorization, both physical and psychiatric comorbidities were related to less PCS and MCS score. However, no significant association between autoimmune comorbidities and HRQOL was found.

ConclusionOur results show a significant association between comorbidities and HRQOL in MS patients.

La esclerosis múltiple (EM) es una enfermedad debilitante acompañada de comorbilidades físicas y mentales. Se sabe poco sobre la relación entre las diferentes comorbilidades y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) en pacientes con EM. Por lo tanto, diseñamos este estudio para evaluar la asociación entre comorbilidades y CVRS.

MétodosEn este estudio transversal se evaluaron 976 pacientes con EM que asistieron a la clínica de EM del Hospital Kashani en Isfahán, Irán. Los datos de comorbilidad se extrajeron de las historias clínicas de los pacientes. Se utilizó la Encuesta breve de 36 ítems (SF-36) para medir la CVRS. En primer lugar se evaluó la asociación entre cada comorbilidad y la CVRS. Luego, las comorbilidades se clasificaron en físicas, psiquiátricas y autoinmunes, y se evaluó la asociación de cada grupo de comorbilidad con la CVRS.

ResultadosLa edad media (DE) y la duración de la enfermedad fueron de 37,58 (9,22) y de 7,41 (5,24) años; la mayoría de los pacientes eran mujeres (82,8%) y tuvieron un curso recidivante (77,1%). La comorbilidad más común fue la migraña (13,6%), seguida del hipotiroidismo (13,5%), el trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo (TOC) (13,5%) y la anemia (11,5%). Hubo una asociación significativa entre la puntuación del componente físico (PCS) de la CVRS y la reducción de la epilepsia, la enfermedad de las arterias coronarias, las enfermedades oculares, el TOC, el trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) y el trastorno límite de la personalidad. En cuanto al componente mental (MCS), la insuficiencia ovárica, el síndrome de ovario poliquístico, el TOC y el TDM tuvieron una asociación con un MCS bajo. Después de la categorización, las comorbilidades tanto físicas como psiquiátricas se relacionaron con una menor puntuación de PCS y MCS. Sin embargo, no se encontró una asociación significativa entre las comorbilidades autoinmunes y la CVRS.

ConclusiónNuestros resultados muestran una asociación significativa entre las comorbilidades y la CVRS en pacientes con EM.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common neurological disease in the central nervous system (CNS) among young adults.1 This disease is characterized by relapsing and progressive courses leading to morbidity and mortality. Additionally, side effects of the disease significantly affect the day-to-day functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of people with MS (pwMS).2,3 Thus, recently, an assessment of the quality of life has become more significant in pwMS in research. However, over the course of the disease, disabling symptoms such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, vision loss, urinary incontinency, and cognitive impairment have considerable adverse effects on patients’ quality of life.2,4 HRQOL is defined as an illness or a treatment impact on an individual's perception of social functioning and well-being, which is negatively affected by MS.2 HRQOL is an appropriate measurement to assess the patients’ sense of the effects of MS on their daily life and life satisfaction.4 There is a robust association between HRQOL and adverse outcomes, including neuropsychiatric complications, accumulation of disability, and inadequate response to therapy.5,6 Assessment of HRQOL and its influential factors are required to design the rehabilitation programs and plan for pwMS.

Comorbidity or co-existence diseases define as the occurrence of multiple physical or psychological health conditions in the same person at the same time.7 pwMS are at higher risk of developing comorbidities than the general population.2 Comorbidities associated with MS include coronary artery disease, gastrointestinal, renal, lung, depression, anxiety, thyroid, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and psoriasis.8 There is a strong interaction between comorbidities and MS. Comorbidity is associated with worse clinical outcomes, high hospitalization rates, and inadequate treatment response.9

Studies on chronic diseases showed that comorbidities negatively influence HRQOL.10 Some research has been carried out to assess the effect of comorbidities on HRQOL in pwMS. However, most studies have focused on a specific comorbidity or only a small number of comorbidities. Limited studies evaluated different comorbidities in pwMS and showed a reverse association between physical and mental comorbidities and HRQOL.11 They also found a dose–response relation between comorbidities and HRQOL, with HRQOL decreasing with an increase in the number of comorbid conditions.12

Identifying comorbidity and its association with HRQOL in different parts of the world is necessary to design appropriate pwMSs’ management and improve patients’ health outcomes. Therefore, we set out the current study to examine the frequency of different comorbidities in Iranian peMS and evaluate their association with HRQOL.

MethodPopulationThis cross-sectional study was carried out in the MS clinic of Kashani hospital, affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, from June 2018 to April 2020. The participants were representative of the people of Isfahan province, which is located in the center of Iran country.13,14 The study has been approved by the Kashani Hospital in Isfahan ethics committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The inclusion criteria were defined as at least 18 years old and diagnosis of MS according to appreciate McDonald diagnostic criteria.15 The exclusion criteria were (a) refusals to participate in the study and (b) current exacerbation. Participants’ demographic and clinical information was extracted from the database,20 including age, gender, duration, and disease severity. The severity of the disease was evaluated using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score.16 The study was approved by the regional bioethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, and written informed consents were obtained from all subjects before enrollment. It should be noted that the latest assessment of the prevalence of MS in Isfahan, Iran, is reported to be 93.06/100,000.17

Comorbidity dataA single reviewer (OM) did a clinical record review of pwMS to determine whether each of them had comorbidities. The data gathered from patients’ anamnesis were confirmed by contacting the corresponding health specialists. To determine whether a patient has comorbidities or not, the reviewer searched for supporting evidence such as laboratory data, previous notes, and imaging on reported comorbidities. Based on patients’ records, the comorbidities were confirmed to be a secondary condition to MS. In case of any discrepancy regarding reported comorbidities between encounters, we focused on the most recent update on that comorbidity status or the encounter focused on the specific comorbidity. The comorbidities were classified into three groups, including physical, psychiatric, and autoimmune.

Physical comorbidities include Epilepsy, Migraine, Hyperlipidemia, Diabetes mellitus type II, Hypertension (HTN), Anemia, Non-autoimmune Hyperthyroidism, Non-autoimmune Hypothyroidism, Ovary failure, Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Fatty liver, coronary artery disease,18 Non-epileptic seizure, Zona, and Eye disorders. Additionally, psychiatry comorbidities encompass Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and borderline personality disorder (BPD). Finally, autoimmune diseases investigated are as follows: Psoriasis, Autoimmune hepatitis, Celiac disease, Myasthenia gravis, Diabetes mellitus type I, Rheumatoid arthritis, Behçet's disease.

Assessment of health-related quality of lifeThe Health Status Questionnaire (SF-36) was used to measure HRQOL that mainly assesses change in health status over the last year.19 The SF-36 consists of 8 subscales, including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, general health perceptions, bodily pain, social function, role limitations due to physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, vitality, and social function. Each domain score ranges from 0 to 100: 0 shows the worst HRQOL, and 100 implies no health state reduction. The subscales were added into two summary scales (Physical and Mental), normalized to a mean of 50 with a standard deviation of 10, with a higher score indicating a better health state. SF-36 results are reported in two categories: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the SF-36 were shown previously.20

Statistical analysisAll data are presented as the frequency for dichotomous variables or mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables. Also, strongly skewed variables were reported as median, ranging between first and third quartile (IQR). A generalized linear model by the robust method was used to evaluate the relationship between physical, psychological, and autoimmune comorbidities with HRQOL (dependent variable), which were adjusted for sex, age at onset, first EDSS, disease duration, and MS type. Additionally, separate models are used to estimate the interactions between the components of comorbidity (physical, psychological, and autoimmune) and sex (reference: male), age, EDSS, age at onset, and disease duration.

HRQOL was considered two summary scores, a physical component score (PCS) and a mental component score (MCS). Initially, the association of each comorbidity with HRQOL was assessed. Then, the association between HRQOL and each comorbidity group (physical, psychiatric, and autoimmune) was evaluated. Due to a small number of reported autoimmune comorbidities, the association between each autoimmune comorbidity and HRQOL wasn’t assessed. Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS Software Version 20 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). A two-tailed p-value<0.05 was considered to be significant.

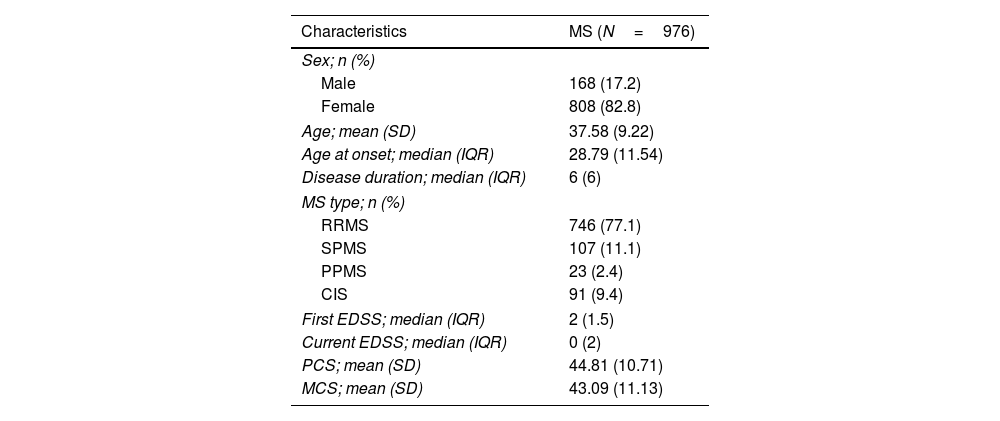

ResultsA total of 976 pwMS was enrolled in this study. 82.8% of them were female and, their mean age was 37.58±9.22 years (range: 17–73 years). Also, the mean score21 of PCS and MCS were 44.81 (10.71) and 43.09 (11.13), respectively. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | MS (N=976) |

|---|---|

| Sex; n (%) | |

| Male | 168 (17.2) |

| Female | 808 (82.8) |

| Age; mean (SD) | 37.58 (9.22) |

| Age at onset; median (IQR) | 28.79 (11.54) |

| Disease duration; median (IQR) | 6 (6) |

| MS type; n (%) | |

| RRMS | 746 (77.1) |

| SPMS | 107 (11.1) |

| PPMS | 23 (2.4) |

| CIS | 91 (9.4) |

| First EDSS; median (IQR) | 2 (1.5) |

| Current EDSS; median (IQR) | 0 (2) |

| PCS; mean (SD) | 44.81 (10.71) |

| MCS; mean (SD) | 43.09 (11.13) |

RRMS: relapsing remitting MS, SPMS: secondary progressive MS, PPMS: primary progressive MS, CIS: clinically isolated syndrome, SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range.

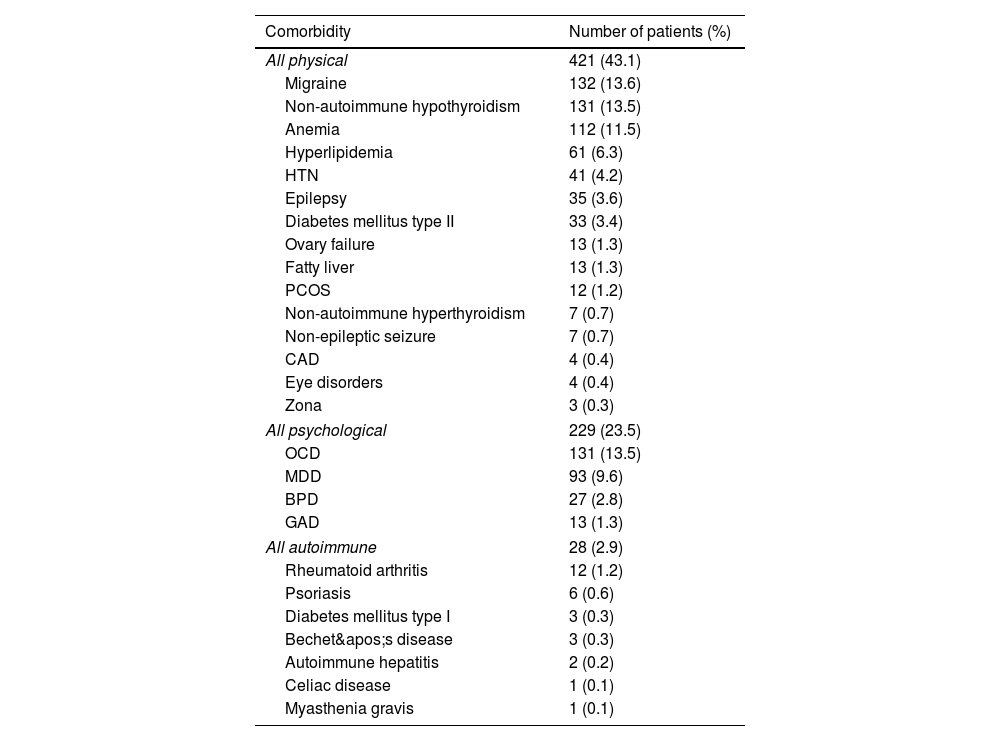

Table 2 shows the frequency of each comorbidity. The most common physical comorbidity was hypothyroidism (13.4%), followed by migraine (13.2%), iron deficiency anemia (11.5%), and hyperlipidemia (6.2%). Among psychiatric comorbidities, OCD affected 131 (13.4%) patients, comorbid MDD involved 93 (9.5%) patients, BPD affected 27 (2.7%), and 13 (1.3%) participants reported GAD. Rheumatoid arthritis (1.2%) and psoriasis (0.6%) were the most common autoimmune comorbidities among participants.

Frequency of comorbidities among participants.

| Comorbidity | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| All physical | 421 (43.1) |

| Migraine | 132 (13.6) |

| Non-autoimmune hypothyroidism | 131 (13.5) |

| Anemia | 112 (11.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 61 (6.3) |

| HTN | 41 (4.2) |

| Epilepsy | 35 (3.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | 33 (3.4) |

| Ovary failure | 13 (1.3) |

| Fatty liver | 13 (1.3) |

| PCOS | 12 (1.2) |

| Non-autoimmune hyperthyroidism | 7 (0.7) |

| Non-epileptic seizure | 7 (0.7) |

| CAD | 4 (0.4) |

| Eye disorders | 4 (0.4) |

| Zona | 3 (0.3) |

| All psychological | 229 (23.5) |

| OCD | 131 (13.5) |

| MDD | 93 (9.6) |

| BPD | 27 (2.8) |

| GAD | 13 (1.3) |

| All autoimmune | 28 (2.9) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 12 (1.2) |

| Psoriasis | 6 (0.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus type I | 3 (0.3) |

| Bechet's disease | 3 (0.3) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 2 (0.2) |

| Celiac disease | 1 (0.1) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 1 (0.1) |

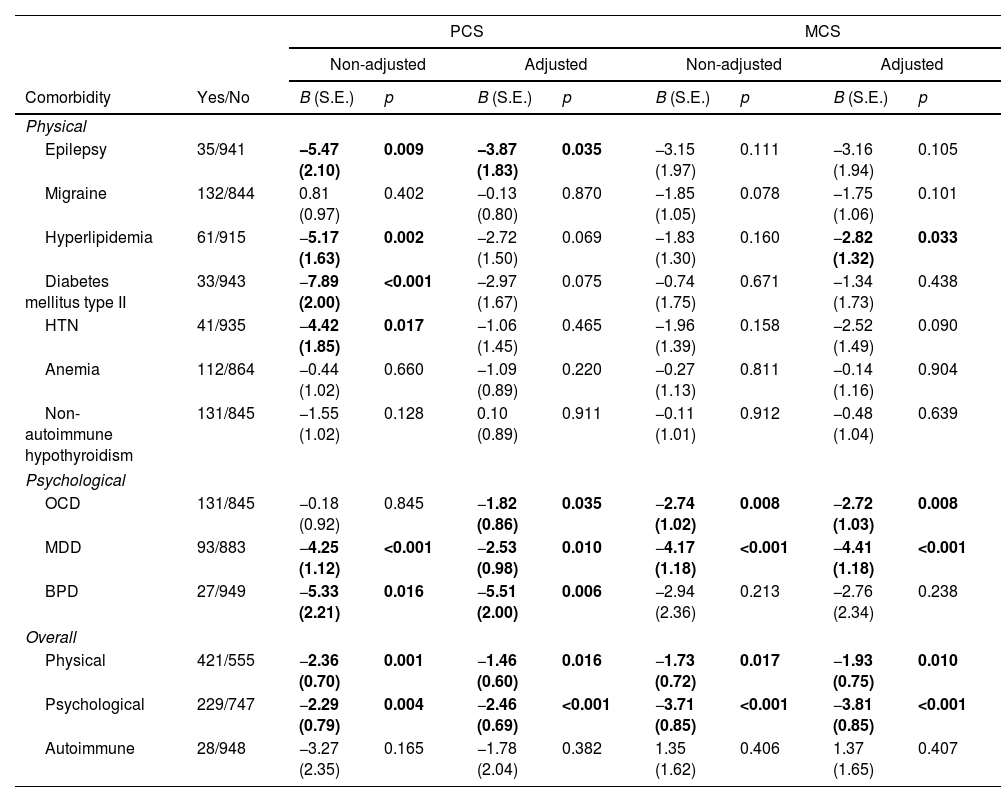

Based on robust generalized linear model, Table 3 shows the presence of physical comorbidities are related to less PCS (non-adjusted model: B=−2.36, p=0.001 and adjusted model: B=−1.46, p=0.016) and MCS (non-adjusted model: B=−1.73, p=0.017 and adjusted model: B=−1.93, p=0.010). Also, the presence of psychological comorbidities is related to less PCS (non-adjusted model: B=−2.29, p=0.004 and adjusted model: B=−2.46, p<0.001) and MCS (non-adjusted model: B=−3.71, p<0.001 and adjusted model: B=−3.81, p<0.001). However, there are no association between the autoimmune comorbidities and PCS/MCS.

Model parameters estimation before (non-adjusted) and after (adjusted) adjusting for sex, age at onset, first EDSS, disease duration, and MS type.

| PCS | MCS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adjusted | Adjusted | Non-adjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

| Comorbidity | Yes/No | B (S.E.) | p | B (S.E.) | p | B (S.E.) | p | B (S.E.) | p |

| Physical | |||||||||

| Epilepsy | 35/941 | −5.47 (2.10) | 0.009 | −3.87 (1.83) | 0.035 | −3.15 (1.97) | 0.111 | −3.16 (1.94) | 0.105 |

| Migraine | 132/844 | 0.81 (0.97) | 0.402 | −0.13 (0.80) | 0.870 | −1.85 (1.05) | 0.078 | −1.75 (1.06) | 0.101 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 61/915 | −5.17 (1.63) | 0.002 | −2.72 (1.50) | 0.069 | −1.83 (1.30) | 0.160 | −2.82 (1.32) | 0.033 |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | 33/943 | −7.89 (2.00) | <0.001 | −2.97 (1.67) | 0.075 | −0.74 (1.75) | 0.671 | −1.34 (1.73) | 0.438 |

| HTN | 41/935 | −4.42 (1.85) | 0.017 | −1.06 (1.45) | 0.465 | −1.96 (1.39) | 0.158 | −2.52 (1.49) | 0.090 |

| Anemia | 112/864 | −0.44 (1.02) | 0.660 | −1.09 (0.89) | 0.220 | −0.27 (1.13) | 0.811 | −0.14 (1.16) | 0.904 |

| Non-autoimmune hypothyroidism | 131/845 | −1.55 (1.02) | 0.128 | 0.10 (0.89) | 0.911 | −0.11 (1.01) | 0.912 | −0.48 (1.04) | 0.639 |

| Psychological | |||||||||

| OCD | 131/845 | −0.18 (0.92) | 0.845 | −1.82 (0.86) | 0.035 | −2.74 (1.02) | 0.008 | −2.72 (1.03) | 0.008 |

| MDD | 93/883 | −4.25 (1.12) | <0.001 | −2.53 (0.98) | 0.010 | −4.17 (1.18) | <0.001 | −4.41 (1.18) | <0.001 |

| BPD | 27/949 | −5.33 (2.21) | 0.016 | −5.51 (2.00) | 0.006 | −2.94 (2.36) | 0.213 | −2.76 (2.34) | 0.238 |

| Overall | |||||||||

| Physical | 421/555 | −2.36 (0.70) | 0.001 | −1.46 (0.60) | 0.016 | −1.73 (0.72) | 0.017 | −1.93 (0.75) | 0.010 |

| Psychological | 229/747 | −2.29 (0.79) | 0.004 | −2.46 (0.69) | <0.001 | −3.71 (0.85) | <0.001 | −3.81 (0.85) | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune | 28/948 | −3.27 (2.35) | 0.165 | −1.78 (2.04) | 0.382 | 1.35 (1.62) | 0.406 | 1.37 (1.65) | 0.407 |

According to the results of this study, patients with epilepsy comorbidity demonstrated less PCS (non-adjusted model: B=−5.47, p=0.009 and adjusted model: B=−3.87, p=0.035) compared to patients without epilepsy. Also, history of Hyperlipidemia, Diabetes Mellitus type II and, HTN were associated with lower PCS only for the non-adjusted model, respectively with (B=−5.17, p=0.002), (B=−7.89, p<0.001) and (B=−4.42, p=0.017). Additionally, regarding physical comorbidity, we observed that only hyperlipidemia is associated with MCS in the adjusted model (B=−2.82, p=0.033). The prevalence of hyperlipidemia was 6.2%.22,23

We observed a significant association between OCD (adjusted model: B=−1.82, p=0.035), MDD (non-adjusted model: B=−4.25, p<0.001 and adjusted model: B=−2.53, p=0.010) and BPD (non-adjusted model: B=−5.33, p=0.016 and adjusted model: B=−5.51, p=0.006) with PCS. Finally, OCD (non-adjusted model: B=−2.74, p=0.008 and adjusted model: B=−2.72, p=0.008) and MDD (non-adjusted model: B=−4.17, p<0.001 and adjusted model: B=−4.41, p<0.001) are associated with lower MCS in patients with MS. Note that, comorbidities with low prevalence (20 patients or less having comorbidities) are excluded from all the analyses except for overall analyses. These physical comorbidities (Non-autoimmune Hyperthyroidism, Ovary Failure, PCOS, Fatty Liver, CAD, Non-epileptic Seizure, Zona and, Eye Disorders) and these autoimmune comorbidities (Psoriasis, Autoimmune Hepatitis, Celiac Disease, Myasthenia Gravis, Diabetes Mellitus type I, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Behçet's Disease), and GAD from psychological comorbidities are excluded to improve the strength of statistical analyses and their generalizability.

DiscussionHealth-related quality of life has been recognized as an essential and measurable instrument to assess the impact of MS on patients’ health. However, the effect of comorbidities on pwMSs’ HRQOL is understudied. In the current study, we explore the impact of various comorbidities on both the physical and mental components of HRQOL in pwMS. We found that both physical and mental comorbid conditions negatively affect the PCS and MCS. However, there was no association between autoimmune comorbidities and HRQOL.

Overall, 43% reported at least one physical comorbid condition. Comparison of our findings with those of other studies12,24 confirms that physical comorbidities are significantly associated with impaired HRQOL in pwMS. Physical comorbidity is related to characteristics of MS, diagnosis delay, disability accumulation, and ineffective care.25–27 Therefore, identifying these diseases and their effect on MS is essential for prioritizing care in patients’ treatments with concurrence diseases.

The frequency of epilepsy in 3.6% of our sample is in line with the reported prevalence of 1.3%28 and 3.5%29 in other MS populations. We observed an association between epilepsy and reduced PCS score. This support previous findings that the co-occurrence of epilepsy in MS is associated with increased disability progression and mortality rate.29,30 The high likelihood of epilepsy in peMS29,31 reinforces the importance of its association with reduced HRQOL.

Based on previous studies, it was expected that vascular comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and dyslipidemia have significant associations with reduced HRQOL scores.32,33 However, we could not find or assess (due to the low prevalence of these comorbidities among our participants) the existence of any association between them and the physical component of HRQOL. The frequency of eye disorders in our MS sample (0.4%) is lower than the prevalence of 14.4% reported in the Australian MS longitudinal study.34 Still, it is close to the rate for glaucoma (1.3%) and cataract (2.1%) reported in a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom.35 Previous research showed that up to 20% of glaucoma and cataract in pwMS might remain undiagnosed and undertreated, increasing visual disability HRQOL.36 These show the necessity of screening for visual diseases in pwMS. Nonetheless, we could not estimate the association between eye disease and PCS/MCS due to the low prevalence of pwMS with eye disorder comorbidity.

Although MS and PCOS are common amongst young women, little attention has focused on the possible relation between these diseases. A wide variety of PCOS manifestations lead to decreased life quality; however, it is not clear how PCOS affects the quality of life in pwMS. Menstrual irregularities and hormonal changes are the most distressing symptoms of PCOS and have the most significant effect on HRQOL.37,38 Patients with PCOS are also more vulnerable to developing psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety.39 All of these are essential determinants of HRQOL for pwMS, showing the adverse effects of PCOS on HRQOL in pwMS.40,41 We did not evaluate the association between PCOS/Ovary Failure and PCS/MCS due to insufficient data. Additionally, the interactions between physical comorbidities and age were found to be significantly and negatively contributing to PCS.

Psychiatric comorbidities were found in 23.5% of our patients, which is lower than the rate of 48%42 and 37%43 reported previously. OCD was the most common condition among psychiatric comorbidities, affecting approximately one in ten pwMS. The frequency of OCD in our sample is higher than the general Iranian population (39) and according to other studies on pwMS.44,45 The second most frequent mental health problem was MDD, affecting 9.6% of our patients, which is substantially lower than previous studies.42,43 This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in methods, evaluation criteria, and assessment tools. We evaluated patients’ medical records, and psychiatric diseases may have been under-reported.

OCD and MDD had unfavorable effects on both physical and mental components of HRQOL, but BPD affected only the physical dimension. Psychological distress symptoms, especially depression, are important determinants of disability progression and HRQOL in pwMS.41,43,46,47 These diseases can affect HRQOL through biological and psychological pathways. Common biological risk factors such as peripheral and central inflammation can develop depression and anxiety in pwMS.48 These conditions can result in brain abnormalities, increased neurodegeneration, and disease progression,44 leading to decreased HRQOL. Mental comorbid medical illnesses also negatively affect behavioral functioning, social functioning, physical activity, and non-adherent to medications49 that can cause impaired HRQOL. Moreover, the interactions between psychological comorbidities and disease duration were significant in our model, and it negatively contribute to PCS. We also found the interaction between psychological comorbidities and age at onset were significantly and positively associating with PCS and MCS. The interaction between psychological comorbidities and age also has similar positive impact on MCS.

PwMS are at increased risk for other autoimmune comorbidities.50 However, a systematic understanding of how these comorbidities contribute to HRQOL is still lacking. No association between autoimmune comorbidity and HRQOL was found. Nevertheless, we believe that small numbers of MS patients with autoimmune comorbidities limit the study's power. Therefore, caution must be applied in the interpretation of these data. In contrast to our research, Lo et al.,51 found that Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease were significantly associated with reduced HRQOL. Further work needs to be carried out to determine how autoimmune comorbidities influence the HRQOL of pwMS. Besides, the interaction between autoimmune comorbidities and being female were significant and positive.

Our study has had some limitations. Because of the cross-sectional design of this study, it is impossible to establish the causality or temporality of the relationship between comorbidities and HRQOL. As mentioned above, comorbidity data is extracted from medical records. It is possible that some diseases, particularly psychiatric disorders, have been underdiagnosed. This study did not evaluate the use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). DMTs can affect the relationship between comorbidities and HRQOL. One source of weakness in this study is the lack of information on treatment, duration, and type and degree of the comorbidities and also level of the control of the comorbidities. Due to differences between studies in methods, definition, and diagnostic criteria, an appropriate comparison and interpretation of findings are difficult. Participants were recruited from only one center. Thus, the ability to generalize these findings to other pwMS is limited.

In conclusion, our studies showed a significant association between comorbidities and health-related quality of life in pwMS. Remarkably, our results have accentuated those comorbidities examined in our study, especially epilepsy, hyperlipidemia, and mental health disorders, have considerable impacts on health-related quality of life in pwMS. Identifying comorbidity early and appropriate intervention and treatment should be considered routine pwMSs’ care to improve disease disability and health-related quality of life. Further longitudinal multi-centric studies are needed to reveal the interaction between comorbidities and HRQOL in pwMS.

Authors’ contributionsAll the authors listed in the manuscript have participated actively in preparing the final version of this manuscript.

Consent for publicationThis manuscript has been approved for publication by all authors. The submitted work has not been published before (neither in English nor in any other language) and that the work is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

FundingWe do not have any financial support for this study.

Conflict of interestThe corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materialThe datasets analyzed during the current study are available upon request with no restriction.