Screening tests are useful to identify cognitive impairments during aging. However, they need to assess different cognitive abilities and be easily accessible to researchers and clinicians. The objective of this work is to develop normative data for the population 55 years of age or older for the Attention, Memory and Frontal Abilities Screening Test (AMFAST).

MethodOne-hundred and fifty-five cognitively healthy participants between 55 and 82 years old were assessed both with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery and the AMFAST. The ability of the AMFAST to identify objective cognitive impairment in the neuropsychological assessment was analysed using binary logistic regression, and sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spe), and positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values were calculated. Normative data were developed using linear regression controlling for the effects of age, gender, and educational level.

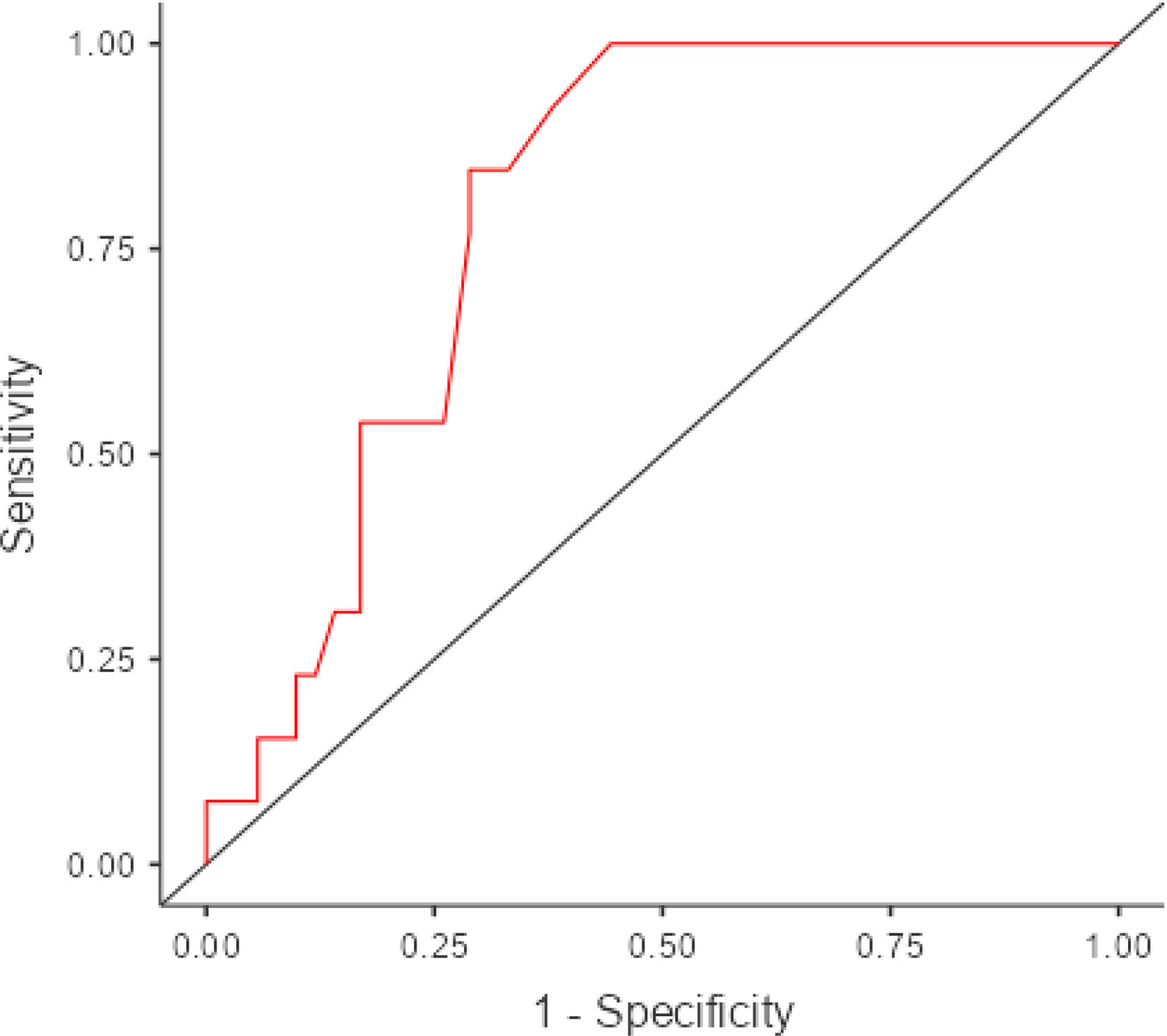

ResultsThe AMFAST total score was statistically associated with age and education, but not with sex. Using 3 or more low scores as the criterion for objective cognitive impairment, the AMFAST total score was associated with the number of low scores on the neuropsychological battery (r = −0.33, p < .001), as well as with objective cognitive impairment (OR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.92-0.98, p = .003). A total score lower than 74 was associated with Sen = 85.71%, Spe = 71.63%, PPV = 23.08%, and NPV = 98.06%.

ConclusionsAs a simple and quick test, the AMFAST could help identify early objective cognitive impairment. Normative data of the Spanish adaptation of the AMFAST for its use in clinical and research are provided.

los tests de screening son útiles para identificar alteraciones cognitivas durante el envejecimiento. No obstante, es necesario que evalúen diferentes capacidades cognitivas y sean de fácil acceso para investigadores y clínicos. El presente trabajo tiene como objetivo desarrollar baremos para población mayor de 55 años del Attention, Memory and Frontal Abilities Screening Test (AMFAST).

Métodose evaluó a 155 personas cognitivamente sanas entre 55 y 82 años con una batería neuropsicológica exhaustiva y el AMFAST. Se analizó mediante regresión logística binaria la capacidad del AMFAST de identificar alteración cognitiva objetiva en la evaluación neuropsicológica, y se calculó la sensibilidad (Sen), especificidad (Esp), y los valores predictivos positivo (VPP) y negativo (VPN). Se desarrollaron datos normativos mediante regresión lineal controlando los efectos de la edad, el sexo y el nivel educativo.

Resultadosla puntuación total del AMFAST se asoció estadísticamente con la edad y la escolaridad, pero no con el sexo. Utilizando 4 o más puntuaciones bajas como criterio de deterioro cognitivo objetivo, la puntuación total en el AMFAST se asoció con el número de puntuaciones bajas en la batería neuropsicológica (r = -0,33, p < 0,001), así como con la alteración cognitiva objetiva (OR = 0,95, 95%CI: 0,92-0,98, p = 0.003). Una puntuación total inferior a 74 se asoció con una Sen = 85,71%, una Esp = 71,63%, un VPP = 23,08% y un VPN = 98,06%.

Conclusionescomo prueba sencilla y rápida, el AMFAST podría ayudar a identificar deterioro cognitivo objetivo de manera precoz. Se aportan datos normativos de la adaptación española del AMFAST para su uso en clínica e investigación.

Advanced age is the main risk factor for the development of cognitive impairment and dementia.1 Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most prevalent type of dementia in older adults,2 but no research to date has demonstrated clear benefits for pharmacological or cognitive interventions.3 Therefore, research efforts have focused on the early identification of cognitive alterations, analysing the characteristics of individuals with subjective memory complaints4 or mild cognitive impairment5 (MCI) and their risk of progressing to AD.

Early identification of cognitive alterations in older adults is achieved with brief screening tests.6 These tests can be administered at any stage of cognitive impairment, from primary care to hospital acute care units or long-term care centres. Screening tests enable rapid assessment of multiple cognitive domains, yielding a total score that supports clinical decision-making.7 The most widely used dementia screening tests are the Mini–Mental State Examination8 (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment9 (MoCA), both of which have been translated and validated in Spanish. However, other brief screening tests may also be used in clinical practice10 despite the lower level of evidence on their potential use.11,12

The use of screening tests is not without controversy. For example, the MMSE has been criticised13 for its lack of clear instructions, its susceptibility to floor and ceiling effects associated with education level, and its bias toward attention or language tasks at the expense of memory assessment. In fact, it only includes one single, very short memory task, in which the patient must learn and recall 3 words through free recall. This approach does not allow assessment of the different stages of learning and memory (encoding, storage, and retrieval), which provide valuable information for detecting cognitive alterations in MCI or AD.14 Furthermore, such screening tests as the MMSE or the MoCA are not freely accessible and require training that may be costly for physicians, limiting their use in clinical practice. As a result, several screening tests have been developed in recent years that are free to use and provide a more comprehensive assessment of multiple cognitive domains.

One recently developed tool is the Attention, Memory, and Frontal Abilities Screening Test (AMFAST).15 The AMFAST is a paper-and-pencil tool consisting of 9 subtests that evaluate attention, processing speed, verbal and visual memory, and executive function in less than 10 minutes. Attention is evaluated with a number cancellation task, verbal memory with a word list and a short story, and executive function with a number-letter switching task and a number inhibition task. Three of the 9 subtests are not scored (word list learning, story learning, and copying a drawing), whereas the remaining 6 are scored 0–15 or 0–20, depending on whether completion time is considered in the score; thus, the instrument yields a total score of 0−100. An interference score is subtracted from the sum score for these 6 subtests if items learnt during the word list task are recalled during delayed recall of the story.

Although it is simple and quick to administer, the AMFAST incorporates different cognitive measures designed to establish the cognitive profile of a wide range of conditions, serving as a highly useful tool for differential diagnosis and guiding further testing. It was specifically developed for the rapid evaluation of frontal-subcortical dysfunction, with the aim of identifying memory alterations or MCI secondary to cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, or HIV infection. For example, the verbal memory subtests include a free recall task and a recognition task. These 2 tasks are particularly useful for determining the origin of memory impairment: while impaired coding is typical of AD,14 retrieval deficits are more commonly observed in disorders with a strong vascular component.16 Likewise, this screening tool evaluates memory using both verbal and visual tasks, which may be useful in identifying patients with amnestic MCI who are at higher risk of progression to AD. Oltra-Cucarella et al.17 found that patients with amnestic MCI who scored low on verbal and visual memory tasks presented a higher risk of progression to AD than those with low scores in only one of the tasks, finding no significant differences between patients with low verbal memory scores and those with low visual memory scores. Likewise, the AMFAST includes a number inhibition task in which the subject is required to respond to certain environmental cues. Participants are presented with numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4, and are instructed to do nothing when hearing the numbers 1 or 3, tap 2 when hearing 4, and tap 4 when hearing 2. Inhibition problems are associated with impaired bilateral frontal lobe metabolism18; therefore, the number inhibition subtest may help to identify individuals at high risk of AD or behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia.

In the validation study, Freilich et al.15 found that the AMFAST total score presented good test-retest reliability (r = 0.87) and excellent inter-rater reliability across 3 examiners (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.95). Furthermore, memory subtest scores were strongly correlated with other memory tasks from a neuropsychological test battery, whereas the executive function subtests were found to be correlated with other executive function tests. Lastly, an AMFAST total score of 70 out of 100 presented 97.2% sensitivity and 95.7% specificity for identifying individuals scoring low on at least 25% of the tasks included in a neuropsychological test battery assessing attention, processing speed, memory, and executive function in a clinical sample that included individuals with AD, unspecified dementia, vascular dementia, MCI, psychiatric disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and rheumatic diseases.

This study presents the translation, validation, and standardisation of the Spanish-language version of the AMFAST, targeting a different population from the original North American population. This version targets Spanish individuals aged 55 or older, providing a novel screening tool for age-related cognitive impairment that may be used in the clinical and research settings.

Material and methodsTest sampleOur sample consisted of healthy volunteers recruited from: 1) the integral programme for people over the age of 55 years of the Miguel Hernández University of Elche (active group [AG], n = 123), and 2) the community (community group [CG], n = 32). Participants in the AG attend university courses at Miguel Hernández University of Elche (https://sabiex.umh.es), covering subjects such as psychology, economics, and law, and participate in cultural and leisure activities including theatre, radio programmes, debates, and trips. Participants in the CG were recruited from the “Personalised Treatment for Obesity” project of the University of Alicante, via e-mail invitation or word of mouth. All subjects participated voluntarily and provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. The inclusion criteria were: 1) age 55 years or older; 2) normal cognitive function with no subjective cognitive complaints; and 3) living independently in the community. The exclusion criteria were: 1) presence of cognitive alterations (eg, MCI); 2) lack of authorisation or consent to participate; and 3) presence of physical alterations (eg, uncorrectable visual problems) preventing neuropsychological assessment. This study was approved by the ethics committees of Miguel Hernández University of Elche (DPS.JOC.01.21) and University of Alicante (ISABIAL 180380).

MaterialsIndividuals with scores ≥ 24 on the MMSE were classified as cognitively healthy.8 Absence of subjective cognitive complaints was established through a semi-structured interview in which participants were asked whether they had noticed a decline in memory, thinking, or daily living functioning over the past months (eg, “do you feel that your memory is worse now than it was 6 months ago?”).19 Independence for daily living activities was defined as a score ≥ 7 on the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living questionnaire.20 All participants were assessed with the same neuropsychological test battery, which included attention tasks (digit span, Trail Making Test), processing speed (Symbol Digit Modalities Test), working memory (Trail Making Test, letters and numbers), visuospatial skills (Judgment of Line Orientation), verbal memory (Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, semantic fluency [animals]), visual memory (Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure), language (Boston Naming Test), executive function (phonemic fluency),21–23 depressive symptoms (30-item Geriatric Depression Scale24), and cognitively stimulating activities.25 To minimise the risk of bias associated with using 2 different sets of normative data, and to enhance comparability of scores between the AG and the CG, neuropsychological test battery performance in both groups was interpreted using community-based norms.26 A scaled score ≤ 6 was interpreted as poor performance.

Attention, memory, and frontal abilities screening testThe AMFAST15 is a quick-to-administer tool consisting of 6 subtests assessing attention, verbal and visual memory, inhibition, working memory, and processing speed. While some subtests (number cancellation, number-letter switching) are scored based on both the number of correct responses and the time required to complete the task, others are scored solely based on the number of correct responses (list memory, spatial memory, story memory) or the number of errors (number inhibition). The total score is calculated by subtracting an interference score (number of verbal interference errors) from the sum score of the 6 subtests, and ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better performance. Translation and validation of the Spanish-language version of the AMFAST was authorised by the authors of the original test. As the instructions are straightforward and involve little linguistic complexity, the test was translated directly by the study’s lead author. The Spanish-language version of the AMFAST is available at https://www.montefiore.org/amfast.

Data analysisComparison between the active group and the community groupContinuous variables were compared between the AG and the CG using the t test, whereas the variable sex was compared using the chi-square test. The discriminative ability of the AMFAST to discriminate between groups was analysed using a binary logistic regression model.

Normative data of the AMFASTWe analysed the influence of age, sex, and education level on AMFAST total score using linear regression,21–23,27 with the variables age and education level centred on the mean. The normality of residuals was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Test-retest reliability at one year (n = 37) and the association between the number of low scores on the neuropsychological test battery and AMFAST total score were assessed with the Pearson correlation coefficient; values of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 were considered to indicate weak, medium, and strong associations, respectively.28 Lastly, the number of impaired tests (NIT) criteria29,30 were used to identify objective cognitive impairment. According to these criteria, the number of low scores depends on the number of tests in the battery, and obtaining one or more low scores may reflect normal cognitive variability. To identify objective cognitive impairment, we used the number of low scores on AMFAST subtests observed in fewer than 10% of participants. Low scores were identified using an empirical frequency distribution and defined as percentile 10 or lower, which corresponds approximately to a z score ≤ –1.28 in a normal distribution. Recent studies have shown that means obtained with samples of 85 or more individuals fall within the 95% confidence interval (CI) of population means in normative studies,31 whereas samples larger than 100 individuals present a true positive rate greater than 95% when a z score ≤ –1.28 is used to interpret linear regression residuals.32 This suggests that our sample (n = 155) was sufficiently large to provide reliable normative data.

Diagnostic utility of the AMFASTTo evaluate diagnostic utility, and in accordance with the NIT criteria,29,30 participants were classified as having objective cognitive impairment on the neuropsychological test battery when the number of low scores equalled or exceeded that observed in less than 10% of the sample. Fewer than 10% of participants obtained low scores on 4 or more neuropsychological tests; therefore, objective cognitive impairment was defined as having 4 or more low scores. The association between AMFAST total score and objective cognitive impairment was analysed with binary logistic regression, and ROC curve analysis was performed to calculate sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values. The cut-off value yielding optimal sensitivity and specificity was calculated with the Youden index.33 Statistical analyses were performed using the packages GAMLj,34 ROCR,35 cutpointr,36 and PPDA (Jamovi).37 The threshold for significance was set at P < .05.

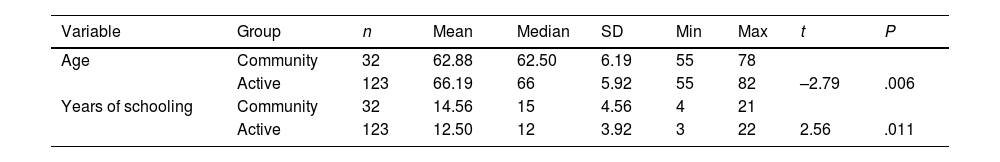

ResultsThe AG and CG showed statistically significant differences in terms of age, sex, and education level, but not in MMSE or AMFAST scores (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were observed in AMFAST total score between the AG and the CG (β = .019, standard error = 0.013, OR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99–1.05; P = .135); therefore, the variable group was not included in linear regression analyses used to calculate AMFAST normative data.

Demographic characteristics of our sample.

| Variable | Group | n | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Community | 32 | 62.88 | 62.50 | 6.19 | 55 | 78 | ||

| Active | 123 | 66.19 | 66 | 5.92 | 55 | 82 | –2.79 | .006 | |

| Years of schooling | Community | 32 | 14.56 | 15 | 4.56 | 4 | 21 | ||

| Active | 123 | 12.50 | 12 | 3.92 | 3 | 22 | 2.56 | .011 |

| Variable | Group | n | % | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (men) | Community | 18 | 56 | ||

| Active | 42 | 34 | 5.23 | .022 |

Max: maximum; Min: minimum; SD: standard deviation; t: t test for independent samples.

AMFAST total score showed a statistically significant association with age and education level, but not with sex (Table 2). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test did not show significant deviation from normality in linear regression residuals (K–S = 0.08; P = .335). Test-retest reliability at one year (mean: 423 days; SD: 94.4; range, 359–674) was r = 0.88 (P < .001). AMFAST total score increased by 1.49 points on retest; this increase was not statistically significant (t = 1.32; P = .194).

Association between demographic variables and AMFAST total score.

| Variable | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | β | df | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| Intercept | 76.48 | 1.06 | 74.38 | 78.58 | 0.00 | 151 | 71.94 | < .001 |

| Age | –0.61 | 0.17 | –0.95 | –0.28 | –0.26 | 151 | –3.60 | < .001 |

| Education level | 1.22 | 0.25 | 0.72 | 1.73 | 0.35 | 151 | 4.80 | < .001 |

| Sex | 1.21 | 2.16 | –3.05 | 5.47 | 0.08 | 151 | 0.56 | .577 |

df: degrees of freedom; SE: standard error; t: t statistic.

To calculate the test’s z score, the predicted score was estimated with the formula [Y = 76.48 + (1.22 × age) − (0.61 × education level)] and subtracted from the observed score; the result was then divided by the standard error of the equation (12.7). Standardisation of the difference between the predicted and observed scores yields a z score; these values can be used to identify objective cognitive impairment (eg, z ≤ –1.28, z ≤ −1.5, z ≤ −1.64).

Table 3 presents the percentage of participants with low scores on AMFAST subtests. None of the participants presented more than 5 low scores. According to the NIT criteria,29,30 objective cognitive impairment is indicated by 3 or more low scores.

Table 4 shows the results of the neuropsychological test battery for the 155 participants. AMFAST total score showed a statistically significant association with the number of low scores on the neuropsychological test battery (r = –0.33, P < .001) and the presence of objective cognitive impairment. Fewer than 10% of participants [n = 14] obtained ≥ 4 low scores on the neuropsychological test battery [OR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92−0.98; P = .003], with an area under the curve of 0.80. Higher AMFAST scores indicated lower risk of presenting objective cognitive impairment. The Youden index identified a score below 74 as the optimal cut-off value, with 85.71% sensitivity, 71.63% specificity, a positive predictive value of 23.08%, and a negative predictive value of 98.06% (Fig. 1). Given that the AMFAST only evaluates attention, memory, and executive function, the analyses were repeated including only the neuropsychological battery tests evaluating these domains. After removing the Boston Naming Test and the Judgment of Line Orientation test, the number of low scores obtained by less than 10% of the sample was ≥ 4. Only 6 participants obtained ≥ 4 low scores. AMFAST total score showed a statistically significant association (OR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91−0.99; P = .030) with presence of objective cognitive impairment when the neuropsychological test battery included tasks assessing attention and processing speed (digit span, Trail Making Test, Symbol Digit Modalities Test), executive function (phonemic fluency, letter-number sequencing), and memory (Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure, semantic fluency) and excluded tasks evaluating language and visuospatial skills.

Descriptive statistics of the neuropsychological test battery (n = 155).

| Variable | Mean | SE | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digit span forwards | 5.43 | 0.10 | 1.22 | 3 | 9 |

| Digit span backwards | 4.26 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 2 | 8 |

| Letter-number sequencing | 4.73 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 2 | 8 |

| TMT-A | 46.97 | 1.48 | 18.4 | 23 | 183 |

| TMT-B | 116.98 | 5.18 | 64.32 | 41 | 368 |

| SDMT | 38.27 | 0.83 | 10.30 | 11 | 58 |

| FCSRT ITR | 43.41 | 0.36 | 4.5 | 25 | 48 |

| FCSRT DTR | 14.75 | 0.14 | 1.68 | 9 | 16 |

| ROCF copy | 27.93 | 0.35 | 4.37 | 15 | 36 |

| ROCF immediate recall | 15.13 | 0.34 | 4.29 | 4.5 | 26.5 |

| ROCF delayed recall | 14.95 | 0.34 | 4.28 | 4.5 | 25 |

| BNT-60 | 54.54 | 0.31 | 3.82 | 38 | 60 |

| Semantic fluency | 20.43 | 0.44 | 5.51 | 7 | 38 |

| Phonemic fluency (“p”) | 14.93 | 0.40 | 4.94 | 3 | 28 |

| Phonemic fluency (“m”) | 13.44 | 0.35 | 4.35 | 4 | 24 |

| Phonemic fluency (“r”) | 12.90 | 0.34 | 4.28 | 3 | 23 |

| JLO | 21.23 | 0.45 | 5.65 | 4 | 32 |

BNT: Boston Naming Test; DTR: delayed total recall; FCSRT: Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; ITR: immediate total recall; JLO: Judgement of Line Orientation; ROCF: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; SD: standard deviation; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SE: standard error; TMT: Trail Making Test.

The aim of this study was to translate, validate, and provide normative data for the AMFAST, a brief cognitive screening test, for the Spanish population aged 55 years and older. The test was administered to 155 community-dwelling adults aged 55 or older, 123 of whom were enrolled in university courses for older adults. We present normative data and the number of low scores indicating objective cognitive impairment.

Our results reveal that AMFAST total score is associated with age and education level, but not sex. These findings stand in contrast with those reported for the original North American sample, in which no significant differences were observed in association with sex, age, or education level. However, the 2 samples are not comparable: the original sample had a mean age of 31.3 years, a lower education level (11.4 years of education), and included multiple ethnic groups (white, Hispanic, African American, Asian, African Caribbean, etc). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies demonstrating that cognitive test performance worsens with age and with lower education level.21–23,38 The absence of an association between test performance and age or education level in the North American sample may be explained by the inclusion of participants younger than 55 years, a population in which age and sex explain a small proportion of the variance in cognitive test performance.39

AMFAST total score did not discriminate between the AG and the CG. Though it might seem surprising, this finding was expected, given that the AMFAST was intended to be a simple test in which only individuals with actual cognitive impairment would perform poorly.15 Given that our participants were cognitively healthy, community-dwelling individuals without cognitive complaints, the absence of differences in test performance between groups was unsurprising. However, as occurs when several cognitive tests are administered, we would expect some individuals to score low on one or more tests.29,30,40,41 Obtaining low scores has been associated with normal variability, which suggests that establishing a diagnosis of cognitive impairment in individuals scoring low on a single test may increase the number of false-positive diagnoses.42 Likewise, it has been suggested that considering both normal variability and the number of low scores may identify individuals with MCI and increased risk of progression to AD with greater accuracy than standard criteria.30 In the present study, fewer than 10% of participants scored low on 3 or more AMFAST subtests. Oltra-Cucarella et al.29 reported that, in the absence of empirical data, fewer than 10% of participants would be expected to present 2 or more low scores on test batteries including 3–9 tests, although considerable variability may be observed even in batteries with the same number of tests. In line with the above, we found an association between the number of low scores on the neuropsychological test battery and AMFAST total score, indicating that a greater number of low scores is associated with lower AMFAST total score. These results should be expected, as a higher number of low scores reflects potential objective cognitive impairment, which is associated with poorer cognitive screening test performance.

In this study, AMFAST total score was found to be useful for discriminating between individuals with and without cognitive impairment who had completed a neuropsychological test battery. Our results indicate that an AMFAST total score > 73 is highly suggestive of absence of cognitive impairment; this information may help to avoid unnecessary healthcare and economic expenditure. However, a score < 74 is associated with low likelihood of presenting actual cognitive impairment. The low specificity and low positive predictive value are explained by the low prevalence of cognitive impairment in our sample (fewer than 10% of participants met criteria for objective cognitive impairment). In these cases, a more thorough examination should be conducted to enable early detection and management of cognitive impairment. Likewise, in line with the results reported by Freilich et al.,15 the AMFAST showed high test-retest reliability at one year, with no statistically significant differences between baseline and follow-up scores. These findings show that AMFAST total scores are highly stable over time, and may therefore be useful to identify cognitive changes during follow-up. The small number of participants with retest scores precludes analysis with a linear regression–based reliable change index, which has been shown to be useful in identifying individuals with MCI and greater risk of progression to AD.43

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample included cognitively healthy individuals without subjective cognitive complaints. This limits the applicability of the Spanish-language version of the AMFAST to individuals with subjective cognitive complaints, which have been associated with greater risk of progression to MCI44 and dementia.45 Furthermore, the lack of a comparison group including individuals with MCI prevents us from determining the test’s psychometric properties for discriminating between cognitively healthy individuals and patients with MCI or other disorders associated with cognitive alterations (eg, depression, schizophrenia). Likewise, objective cognitive impairment was identified using the NIT criteria; as a result, our sample is small, as it included fewer than 10% of the participants (n = 14). Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. The Spanish-language version of the AMFAST may help to identify older adults without cognitive complaints who do not present cognitive impairment. However, in patients with subjective memory or cognitive complaints, or those scoring < 74 on the AMFAST, a more comprehensive neuropsychological test battery should be administered to detect objective cognitive impairment.

Another relevant limitation is the lack of comparison with other screening tests. We used the MMSE to confirm the absence of overall cognitive impairment, which was one of the study’s inclusion criteria; however, this test’s ability to determine which individuals will progress to MCI or dementia has been questioned due to its low sensitivity and specificity.46 Therefore, more studies with the AMFAST are needed to further establish its predictive ability to identify individuals at high risk of progression from normal cognition to MCI or dementia and from MCI to dementia. Finally, our data are drawn from a sample of Spanish individuals, which prevents extrapolation to other Spanish-speaking populations. Several studies have reported differences in neuropsychological test performance across Spanish-speaking countries,47,48 therefore, this Spanish-language version of the AMFAST should be validated according to the specific characteristics of each country before use.

ConclusionsOur study presents the first translation and international validation of the AMFAST, and provides normative data for the Spanish population aged 55 years and older. These regression-based normative data account for the effects of sex, age, and education level, allowing the observed scores to be compared with predicted scores. The size of our sample ensures that the percentage of true positives detected using this type of regression-based tools is higher than 95% when a cut-off z score ≤ –1.28 is applied.32 The AMFAST is a brief screening tool that evaluates several cognitive domains. Unlike the MMSE and MoCA, the AMFAST is freely accessible and evaluates different stages of memory, which may allow for more accurate identification of cognitive profiles useful for discriminating different neurological diseases. Further research is needed to determine whether the AMFAST presents superior psychometric properties for identifying MCI and dementia compared to other screening tests, and whether its subtests are differentially associated with different types of MCI or dementia.

FundingThis study was partially funded by the Valencian regional ministry of innovation, universities, science, and digital society(project NEUROPREVENT GV/2021/139).

None.