During the last years, lifestyle has worsened along the entire European population, causing an alarming boom-up regarding overweight and obese people. Pediatric population is also influenced in this sense, which may predispose to suffer from several diseases in adulthood. Educational interventions at early ages could be an effective strategy to face this situation.

AimTo describe the impact of an educational intervention about healthy lifestyle in adolescents.

MethodsA quasi-experimental study analyzing the knowledge of high school students, before and after a brief educational intervention based on a self-elaborated questionnaire including questions from the validated questionnaire CAPA (from Spanish, Conocimientos en Alimentación de Personas Adolescentes).

ResultsThe results of this study show a significant increase in knowledge about healthy lifestyles in the study population after the educational intervention (14.3±3.8 vs. 16.5±4.5; p<0.001). In addition, this improvement presents an asymmetric distribution according to gender (13.2±3.6 vs. 14.9±4.6; p=0.002 in men; 15.6±3 vs. 18.1±3.6; p<0.001 in women) and the type of educational center (14.17±3.6 vs. 16.48±4.17; p<0.001 in public schools and 14.86±4.15 vs. 16.54±5.32; p=0.047 in private schools). Parents’ educational level was associated with improvement in knowledge about healthy lifestyles (13.44±2.9 vs. 15.67±5.37; p=0.132 at low level, 14.22±3.42 vs. 16.9±4.68; p<0.001 at medium level and 15.75±3.3 vs. 17.39±4.5; p=0.022 at high level).

ConclusionEducational intervention taught by primary health care professionals is a useful and efficient tool for the acquisition of nutritional and healthy lifestyle knowledge in adolescents.

Durante los últimos años, el estilo de vida de la población europea ha empeorado notablemente, provocando un alarmante incremento de sobrepeso y obesidad. El público pediátrico se ha visto también afectado, aumentando la predisposición a sufrir importantes enfermedades en la edad adulta.

ObjetivoDescribir el impacto de una intervención educativa sobre un estilo de vida saludable en adolescentes.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio cuasi experimental analizando el entendimiento de estudiantes de instituto, antes y después de una breve intervención educativa con base en una encuesta elaborada por los investigadores apoyada en el cuestionario validado conocimientos en alimentación de personas adolescentes (CAPA).

ResultadosLos resultados de este trabajo muestran un incremento significativo de los saberes acerca de estilos de vida saludables en la población de estudio (14,3 ± 3,8 vs. 16,5 ± 4,5; p < 0,001). Además, este incremento se presenta de manera asimétrica de acuerdo con el sexo (13,2 ± 3,6 vs. 14,9 ± 4,6; p = 0,002 en hombres; 15,6 ± 3 vs. 18,1 ± 3,6; p < 0,001 en mujeres) y al tipo de centro educativo (14,17 ± 3,6 vs. 16,48 ± 4,17; p < 0,001 en institutos públicos y 14,86 ± 4,15 vs. 16,54 ± 5,32; p = 0,047 en privados). El nivel educativo de los padres también se asoció con una mayor adquisición de conocimientos sobre estilos de vida sanos (13,44 ± 2,9 vs. 15,67 ± 5,37; p = 0,132 bajo nivel, 14,22 ± 3,42 vs. 16,9 ± 4,68; p < 0,001 medio y 15,75 ± 3,3 vs. 17,39 ± 4,5; p = 0,022 alto).

ConclusiónUna intervención educativa impartida por profesionales de la salud resulta una herramienta útil y eficiente para la correcta adquisición de conocimientos sobre estilos de vida saludables y nutrición en adolescentes.

Obesity and overweight are defined as an excessive accumulation of fat which becomes detrimental to health. During the last few years, the number of people who suffer from obesity has increased irrespective of geographical locality, ethnicity or socioeconomic status,1 as well as age, affecting both children and adults.2 Currently, 39% of worldwide population is overweight and 13% of adults suffer from obesity.3 More specifically, in Spain around 16% of people are described to be obese currently. Regarding young population, the obesity estimated prevalence is 19.7%, comprising 14.7 million of children and teenagers.4 Regrettably, these rates are predictive to keep increasing, thus affecting to worsen quality of life of those patients and increasing health costs in short, medium and long terms.5–7Consequently, World Health Organization (WHO) declared obesity as a global epidemic based on the great impact on its associated morbimortality, which impairs substantially the quality of life of people suffering from it, being the cause of 4.7 million deaths per year and causing a reduction of 148 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).8,9

Far from improving, in recent years there has been observed a deterioration in nutritional habits, which join to the increase in sedentary lifestyle worldwide is alarmingly booming up the risk of developing overweight and obesity.8,10 Additionally, several authors and experts have pointed out that one of the most worrying reasons of this increase is the higher and growing prevalence of childhood-obesity, which is described to be most likely to develop obesity complications during adulthood, both metabolic and cardiovascular.4,11

In fact, the World Health Report published in 2002 a study about the association of different risk factors with premature death, finding that the majority of them were directly related to diet and physical exercise. This context at the epidemiological level, the high prevalence and mortality of obesity has led the mobilization of countries and international organizations that have begun to carry out some initiatives to try to put an end to this serious situation.12,13

The management of this pathological disorder comprehends a multidisciplinary approach, becoming more important tackling it in early ages, for instance with educational programs targeting young students.14 Thus, educational interventions aiming children and adolescents could help them to learn healthy lifestyle habits from an early age, as well as to improve their quality of life and prevent or delay the onset of illnesses related to these bad habits, such as obesity.15,16

Thus, the main objective of this study was based on describing the impact of an educational intervention about nutrition and lifestyle in adolescents.

Materials and methodsDesign and target population of studyA quasi-experimental study was carried out with students in the 3rd year of high school from six different educational centers of Alcázar de San Juan who agreed to participate in the study. Our study was reported according to the SQUIRE-EDU (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education) guideline.17

ProcedureThe research project was presented in the high schools, requesting for the consent of the principals and their participation in the study. Once the consent was given, the questionnaires were provided to the centers so the students could complete it before the educational intervention. Questionnaire (Supplementary Material) was made and adapted to the age and level of knowledge of the students surveyed, including questions from the validated questionnaire CAPA (from Spanish, Conocimientos en Alimentación de Personas Adolescentes).18 Afterwards, an educational intervention about nutrition and healthy lifestyles was carried out by two primary health care nurse specialists, with approximately 45min of duration. Materials were provided in person and they consisted of videos, practical examples, and clear and updated information about how early modifications in our lifestyle may impact in the development of long terms disorders. Then, around 4 weeks later, the questionnaire was handed out again in order to assess the acquisition and consolidation of the nutritional knowledge and, in this way, the effectiveness of the educational intervention.

VariablesThe questionnaire used for this study included sociodemographic information (age, sex, type of high school and parents educational level), nutritional habits, knowledge about food and nutrients, and lifestyle. Each question scores one point, qualifying globally the knowledge of the students as low≤7 points, moderate 8–15 points and high≥16 points. Additionally, the qualifications depending on each section were also recorded, establishing the next cutoffs: nutritional habits (low≤1, moderate 2–3, high 4–5), knowledge about food and nutrients (low≤3, moderate 4–7 and high 8–11) and lifestyle (low≤3, moderate 4–5 and high 6–8).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of all the variables included in the study was carried out, expressing the quantitative variables by measures of central tendency (mean or median) accompanied by measures of dispersion (standard deviation or interquartile range) according to the nature of the variable. In the pre–post comparison of the educational intervention, the t-Student test was used for the quantitative variables or the Wilcoxon test when it was necessary, while the χ2 test or the Fisher's exact test were used for the qualitative variables. Statistical significance was assumed at a p<0.05 level. All the analysis was carried out with the statistical software PASW (v18.0; SPSS Inc.).

Ethical aspectsThis study was carried out in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki promulgated by the World Medical Association and after the authorization of the Ethics Committee of GAI Alcázar de San Juan (code 7-D). Information remained anonymized along the whole study, and informed consent was not necessary due to the design of the study.

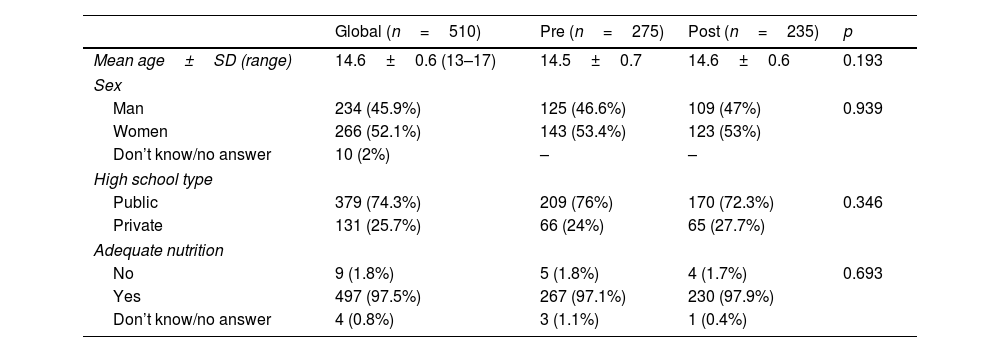

ResultsA total of 275 pre-intervention questionnaires and 235 post-intervention questionnaires were completed, but without differences regarding the descriptive variables between pre-post groups. This comprised a participation of 74.56% of students from the high school included. The mean age of surveyed students was 14.6±0.6 years,13–17 being 45.9% males and 52.1% females (2% not specified), and describing almost every student (97.5%) their diet as healthy. The descriptive data are expressed in Table 1.

Description of the main sociodemographic variables of the students included in the study.

| Global (n=510) | Pre (n=275) | Post (n=235) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age±SD (range) | 14.6±0.6 (13–17) | 14.5±0.7 | 14.6±0.6 | 0.193 |

| Sex | ||||

| Man | 234 (45.9%) | 125 (46.6%) | 109 (47%) | 0.939 |

| Women | 266 (52.1%) | 143 (53.4%) | 123 (53%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | 10 (2%) | – | – | |

| High school type | ||||

| Public | 379 (74.3%) | 209 (76%) | 170 (72.3%) | 0.346 |

| Private | 131 (25.7%) | 66 (24%) | 65 (27.7%) | |

| Adequate nutrition | ||||

| No | 9 (1.8%) | 5 (1.8%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0.693 |

| Yes | 497 (97.5%) | 267 (97.1%) | 230 (97.9%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | 4 (0.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

Regarding the questions related to the different items of the nutritional and lifestyle habits, the intervention resulted effective since surveyed students answered correctly more queries post educational intervention than pre-intervention (Table 2). In this way, four out of five questions of “Nutritional habits” part, six of eleven of “Food and nutrients” section, and two out of eight regarding their “Lifestyle” showed a statistically significant increase (p<0.05), but the prevailing trend is to get right more frequently after the intervention (Fig. 1).

Proportion of answers in the different questions of the questionnaire before and after educational intervention.

| Pre (n=275) | Post (n=235) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How many times do the experts recommend to eat in a day? | |||

| A. Three | 29 (10.7%) | 12 (5.2%) | 0.040 |

| B. Five | 150 (55.4%) | 119 (51.1%) | |

| C. Three to five | 89 (32.8%) | 99 (42.5%) | |

| D. Whenever you feel hungry | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 2. Drinking water is basic in a healthy diet. Choose the correct affirmation | |||

| A. Drinking water could increase your weight | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0.100 |

| B. We should drink at least 1.5–2l/day | 264 (97.1%) | 223 (95.7%) | |

| C. Water has calories and makes you feel bloated | 2 (0.7%) | 7 (3%) | |

| D. Water is as healthy as soft drinks. | 5 (1.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 3. Breakfast must contribute to the daily diet: | |||

| A. 10% calories | 17 (6.6%) | 14 (6%) | <0.001 |

| B. 15% calories | 72 (28.1%) | 48 (20.7%) | |

| C. 20–25% calories | 103 (40.2%) | 139 (59.9%) | |

| D. More than 25% calories | 64 (25%) | 31 (13.4%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 4. A balanced breakfast must contain: | |||

| A. Bread, dairy and protein-rich foods | 49 (18.9%) | 36 (15.5%) | 0.009 |

| B. Dairy, fruits and cereals | 91 (35.1%) | 64 (27.5%) | |

| C. Bread, sausages and dairy | 0 | 6 (2.6%) | |

| D. Dairy, fruits and foods rich in protein | 119 (45.9%) | 127 (54.5%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 5. How many portions of fruits and vegetables do experts recommend to eat per day? | |||

| A. One fruit, three vegetables | 15 (5.6%) | 16 (6.9%) | 0.085 |

| B. Three vegetables and three or more fruits | 108 (40.6%) | 72 (31%) | |

| C. Three fruits and two vegetables | 115 (43.2%) | 124 (53.4%) | |

| D. Three fruits and one vegetable | 28 (10.5%) | 20 (8.6%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 6. The energy needs of a person depend on: | |||

| A. Weight and height | 9 (3.3%) | 8 (3.4%) | 0.719 |

| B. Age | 11 (4.1%) | 13 (5.6%) | |

| C. Physical activity | 12 (4.5%) | 14 (6%) | |

| D. All of them | 237 (88.1%) | 197 (84.9%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 7. What is the Harvard method? | |||

| A. A way of cooking. | 6 (2.5%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0.013 |

| B. Dividing a plate into 50% protein, 25% carbohydrates and 25% bread. | 72 (30.3%) | 44 (19.2%) | |

| C. Divide a plate into 50% fruits and vegetables, 25% carbohydrates and 25% proteins. | 159 (66.8%) | 173 (75.5%) | |

| D. It would only contain vegetables and salad. | 1 (0.4%) | 6 (2.6%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 8. A group of foods are called regulators. Which is the least rich in vitamins and minerals? | |||

| A. Apple | 17 (6.4%) | 15 (6.4%) | 0.785 |

| B. Tomato | 22 (8.3%) | 19 (8.1%) | |

| C. White bread | 194 (73.5%) | 179 (76.5%) | |

| D. Walnuts | 31 (11.7%) | 21 (9%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 9. Which of the following foods is considered “builder”? | |||

| A. Extra virgin olive oil | 79 (32.4%) | 73 (31.2%) | 0.003 |

| B. Sugar | 90 (36.9%) | 55 (23.5%) | |

| C. Egg | 70 (28.7%) | 99 (42.3%) | |

| D. Pear | 5 (2%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 10. What are the fats we should consume in less quantity? | |||

| A. Monounsaturated | 13 (4.9%) | 13 (5.6%) | 0.371 |

| B. Polyunsaturated | 27 (10.2%) | 32 (13.7%) | |

| C. Saturated | 216 (81.8%) | 186 (79.5%) | |

| D. Vegetable | 8 (3%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 11. Which of the following fish is considered as oily fish? | |||

| A. Sole | 61 (24.1%) | 13 (5.6%) | <0.001 |

| B. Cod | 57 (22.5%) | 29 (12.4%) | |

| C. Golden | 36 (14.2%) | 16 (6.8%) | |

| D. Trout | 99 (39.1%) | 176 (75.2%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 12. How much meat do you have to eat a week? | |||

| A. Indifferent | 17 (6.5%) | 7 (3%) | 0.004 |

| B. 1–3 servings | 171 (65%) | 125 (53.9%) | |

| C. 4–5 servings | 65 (24.7%) | 89 (38.4%) | |

| D. More than 5 servings | 10 (3.8%) | 11 (4.7%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 13. Whole-grain foods: | |||

| A. Are low in calories | 54 (20.8%) | 26 (11.3%) | 0.029 |

| B. Are low in sugar | 32 (12.3%) | 27 (11.7%) | |

| C. Are low in salt | 8 (3.1%) | 11 (4.8%) | |

| D. Are rich in dietary fiber | 166 (63.8%) | 167 (72.3%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 14. What characterizes the Mediterranean diet? | |||

| A. Daily consumption of meat | 25 (9.9%) | 11 (4.8%) | 0.103 |

| B. High consumption of fruits and vegetables | 126 (50%) | 128 (55.4%) | |

| C. High consumption of dairy products and moderate of saturated fats | 48 (19%) | 51 (22.1%) | |

| D. Daily consumption of olive oil and wine | 53 (21%) | 41 (17.7%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 15. Of these foods, which should be taken sporadically? | |||

| A. Bread | 18 (6.8%) | 15 (6.4%) | 0.318 |

| B. Chocolate cookies | 190 (71.4%) | 183 (78.2%) | |

| C. Rice | 29 (10.9%) | 18 (7.7%) | |

| D. Fruit | 29 (10.9%) | 18 (7.7%) | |

| 16. Excessive salt consumption can cause: | |||

| A. Arterial hypertension | 234 (88%) | 207 (89.2%) | 0.205 |

| B. Dental cavities | 8 (3%) | 9 (3.9%) | |

| C. Anemia | 5 (1.9%) | 8 (3.4%) | |

| D. None | 19 (7.1%) | 8 (3.4%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 17. Regarding alcohol consumption: | |||

| A. One a week is healthy | 21 (8.1%) | 14 (6%) | 0.199 |

| B. Getting drunk every weekend may be a problem | 144 (55.8%) | 148 (62.8%) | |

| C. Alcohol has few calories | 9 (3.5%) | 11 (4.7%) | |

| D. An alcoholic person is who drinks everyday | 84 (32.6%) | 59 (25.4%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 18. Regarding alcohol consumption: | |||

| A. Only in weekends is not bad | 19 (7.3%) | 14 (6%) | 0.894 |

| B. Is good for the heart | 8 (3.1%) | 8 (3.4%) | |

| C. Does not help to overcome fatigue, to be animated or in shape | 218 (83.5%) | 199 (85.4%) | |

| D. All are correct | 16 (6.1%) | 12 (5.2%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 19. Regarding tobacco: | |||

| A. Quitting smoking makes you fat. | 17 (6.5%) | 11 (4.7%) | 0.732 |

| B. Low nicotine cigarettes do not harm, they are not carcinogenic | 9 (3.4%) | 7 (3%) | |

| C. It generates dependence | 214 (81.7%) | 198 (85.3%) | |

| D. Rolling tobacco is less harmful than traditional tobacco | 22 (8.4%) | 16 (6.9%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 20. Which of the following alterations are considered eating disorders? | |||

| A. Obesity and dyslipidemia | 26 (10.2%) | 23 (10.2%) | 0.020 |

| B. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa | 129 (50.4%) | 143 (63.3%) | |

| C. Diabetes mellitus and celiac disease | 26 (10.2%) | 13 (5.8%) | |

| D. All the previous | 75 (29.3%) | 47 (20.8%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 21. The “Zero Sugar” drinks: | |||

| A. Are healthy, even if their consumption is abusive. | 11 (4.2%) | 8 (3.4%) | 0.326 |

| B. They help to lose weight | 7 (2.6%) | 11 (4.7%) | |

| C. Although not containing sugars, it does contain sweeteners such as aspartame. | 245 (92.5%) | 209 (89.7%) | |

| D. They have many nutrients. | 2 (0.8%) | 5 (2.1%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 22. Physical activity in adolescents: | |||

| A. Should include moderate aerobic physical activity for at least 150–300min per week | 40 (15.1%) | 34 (14.6%) | 0.094 |

| B. Should limit time spent on sedentary activities | 23 (8.7%) | 35 (15%) | |

| C. Should include muscle-strengthening activities 2 or more days a week. | 49 (18.5%) | 31 (13.3%) | |

| D. All are correct | 153 (57.7%) | 133 (57.1%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 23. Physical activity: | |||

| A. Improves mental health | 23 (8.7%) | 32 (13.8%) | 0.109 |

| B. Improves cognitive outcomes | 44 (16.7%) | 32 (13.8%) | |

| C. Reduces sleep time | 149 (56.7%) | 139 (59.9%) | |

| D. Reduces the risk of overweight/obesity | 47 (17.9%) | 29 (12.5%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

| 24. How many hours are recommended to sleep daily? | |||

| A. 6h | 3 (1.1%) | 7 (3%) | 0.096 |

| B. At least 7–8h | 244 (90.7%) | 210 (90.1%) | |

| C. More than 10h | 11 (4.1%) | 13 (5.6%) | |

| D. 12h | 11 (4.1%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Don’t know/no answer | – | – | |

Consequently, educational intervention improved the knowledge of students in the three parts of the survey, observed both in the overall score of each part (nutritional habits part 2.5±1 pre-intervention vs. 3±1.2 post intervention (p<0.001), food and nutrients 6.4±2.1 vs. 7.6±2.3 (p<0.001), and lifestyle 5.4±1.8 vs. 5.9±1.9 (p=0.01)), as well as in the proportion of students stating high knowledge (nutritional habits part 14.5% pre-intervention vs. 37.4% post-intervention (p<0.001), food and nutrients 33.1% vs. 57.9% (p<0.001), and lifestyle 53.8% vs. 63% (p=0.021)) (Fig. 2).

Finally, the global questionnaire score revealed that the educational intervention improved the general knowledge in the students with an increase of 2.5 points in overall score (14.3±3.8 vs. 16.5±4.5; p<0.001), classifying 65.1% as high knowledge.

When comparing the improvement in pre-post knowledge between sex, globally women started in higher score, and reaching also higher punctuation after intervention (13.2±3.6 vs. 14.9±4.6; p=0.002 in men and 15.6±3 vs. 18.1±3.6; p<0.001 in women). In this sense, the observed increase turns out to be greater in women than in men (2.5 points vs. 1.7 points).

A subgroup analysis between the types of educational center (public vs. private) was also performed. In this way, the intervention seemed to be significantly effective in both public (14.17±3.6 pre-intervention vs. 16.48±4.17 post-intervention; p<0.001) and private schools (14.86±4.15 vs. 16.54±5.32; p=0.047). However, the private centers started with a higher proportion of students with score related to high knowledge (14.86 vs. 14.17), the improvement after the intervention was greater in public centers than in private ones (2.31 points vs. 1.68 points), which provided public centers to have higher proportion of students with high knowledge after intervention (Table 3).

Comparison between public and private study center.

| Public | Private | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n=209) | Post (n=170) | p | Pre (n=66) | Post (n=65) | p | |

| Mean Global Score±SD (range) | 14.17±3.68 | 16.48±4.17 | <0.001 | 14.86±4.15 | 16.54±5.32 | 0.047 |

| Low knowledge (0 – 7) | 10 (4.8%) | 7 (4.1%) | <0.001 | 4 (6.1%) | 5 (7.7%) | 0.074 |

| Medium knowledge (8 – 15) | 123 (58.9%) | 52 (30.6%) | 31 (47%) | 18 (27.7%) | ||

| High knowledge (16 – 24) | 76 (36.4%) | 111 (65.3%) | 31 (47%) | 42 (64.6%) | ||

Finally, regarding the educational level of the parents, we also wanted to analyze whether it could interfere with the level of knowledge of food and nutrition, as well as the efficiency of the educational intervention (Table 4). In this sense, it is observed that there is a significant improvement in knowledge before-after in all students, regardless of whether their parents had low (primary studies), moderate (secondary studies) or high knowledge (university studies) in the overall score (13.44±2.9 vs. 15.67±5.37; p=0.132 at low level, 14.22±3.42 vs. 16.9±4.68; p<0.001 at secondary studies and 15.75±3.3 vs. 17.39±4.5; p=0.022 at university studies). If the increases in relation to this global score are analyzed, they were 2.23 when the educational level of the parents was low, 2.27 when it was moderate and 1.64 when it was high, presenting the latter group a higher score, both before and after the intervention. Similarly, in relation to the level of knowledge, it was also possible to observe an increase in the proportion of students who presented high post-intervention knowledge in those whose parents had a moderate and high level of education.

Comparison between educational level of the parents.

| Low | Moderate | High | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n=18) | Post (n=18) | p | Pre (n=151) | Post (n=122) | p | Pre (n=64) | Post (n=56) | p | |

| Mean Global Score±SD (range) | 13.44±2.91 | 15.67±5.37 | 0.132 | 14.22±3.42 | 16.49±4.68 | <0.001 | 15.75±3.33 | 17.39±4.48 | 0.022 |

| Low Knowledge (0–7) | 0 (0%) | 1(5.6%) | 0.053 | 6 (4%) | 7 (5.7%) | 0.04 | 2 (3.1%) | 3 (5.41) | 0.024 |

| Medium Knowledge (8–15) | 12 (66.7%) | 5 (27.8%) | 93 (61.6%) | 40 (32.8%) | 26 (40.6%) | 10 (1.79%) | |||

| High Knowledge (16–24) | 6 (33%) | 12 (66.7%) | 52 (34.4%) | 75 (61.5%) | 36 (56.3%) | 43 (76.8) | |||

Our results obtained from this study show the effectiveness of educational intervention to reach an increase in the healthy lifestyles-related knowledge in high school students.

The average age of the surveyed was similar to other studies performed both nationally and internationally.19–21 In this way, many of these studies have shown that this type of intervention would also be effective in younger populations, such as schoolchildren between 6 and 12 years of age. The importance of this kind of intervention remains in the prevention of some disorders related to bad nutritional habits and sedentary lifestyle, such as obesity, due to its increasing prevalence in young population and the short, medium and long-terms related-complications.22–24 In this regard, there are some existing programs in Spain, for instance Perseo program, which started in 2006. This is a reference school pilot program against obesity based on an educational intervention promoting, mainly, physical activity targeting scholar young students and their relatives taught by trained teachers.19,25

Additionally, our results show how this intervention can also be carried out by Health care professionals, specifically Primary Health Care nursing specialists. Nurses have a central role in education for citizenship and in promoting healthy habits, especially important in childhood and adolescence.26

According to our results, it is observed that women start with a higher level of prior knowledge about healthy lifestyles than men and, despite the fact that both genders increased their level of knowledge after the intervention, women keep higher levels of knowledge. These results are slightly controversial, since they agree with some previously conducted studies,27–29 but oppose another report.30 These differences could be due to age of students included, since in the case in which the male gender obtained a greater efficiency of the intervention, the mean age of the study population was 8.4 years, while in the rest it was approximately 11 years, which is closer to that shown by the population of this work. In this regard, the possible explanation could be related to the impact that is currently having social media in improving healthy habits31 and the fact of women using information and communication technologies (ICT) more frequently than men.32

When comparing the type of educational center, our results show how private centers started with higher knowledge than public ones in our survey, both before and after the educational intervention. However, the increase observed is bigger in public schools in comparison with private centers. To our knowledge, this is the first study which applied this kind of comparison, but we consider it could be used to set the basis of educational programs by Governments which promote healthy lifestyle focused on students from public centers in order to reach equal knowledge between centers.

Our study presents some limitations, being the most important the lack of follow-up of the surveyed students, which might impair the translation to real-life. Furthermore, several students data were lost after intervention, which join to the anonymity, limit the comparisons and traceability between subpopulations. In contrast, this anonymity also comprise a study strengthen, which adds up to the fact that our survey is based on another validated questionnaire. Additionally, the post-intervention questionnaire was not performed just after the intervention. This proves that the knowledge obtained remains over the time, since following the Hermam Ebbighaus curve established that the memory decreases considerably after some days33 and, in our case, the students kept showing higher knowledge of healthy habits and lifestyle.

Taking into account all the results obtained in this study, it is clear that nutritional interventions are effective when carried out at an early age. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to extrapolate these interventions to adulthood in people who suffer from obesity or overweight, and measure their effectiveness. For this reason, this study could help to develop future prospective and longer follow-up periods after intervention studies that enlarge the knowledge about the efficacy of professional interventions at an early stage in order to avoid pathologies related to nutritional habits in the long terms. Additionally, it would be interesting to involve families in this type of intervention, since in most cases relatives may be responsible for eating habits. Therefore, it would be necessary to deepen about the impact of these educational interventions aiming both scholar population and their families in long terms. In these terms, the profile of professionals who best suit to make students and relatives to understand correctly the importance of following healthy lifestyle are health care workers. With our results, we prove the effectiveness is evidenced when this intervention is performed by nurses, strengthen the impact and the role that these professionals have in the society's health and habits.

ConclusionCarrying out a brief educational intervention given by primary health care nurses has demonstrated to be a useful and effective tool in the acquisition of nutritional knowledge and healthy lifestyle habits. This acquisition of knowledge could have an impact on improving the lifestyles of the population, although future studies should verify this hypothesis. Thus, it would be necessary to continue carrying out this type of educational interventions aiming scholar population, and maybe their families, in order to achieve a good education in relation to nutrition and healthy lifestyles from early ages. This could help to prevent the development of overweight, obesity and other associated diseases in the future, providing good health and quality of life.

Authors’ contributionStudy design: JCMS, CVM, AAA.

Data collection: JCMS, CVM.

Data analysis: LGR, AAA, ATM.

Study supervision: AAA, ATM.

Manuscript writing: JCMS, CVM, LGR, AAA, ATM.

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: LGR, AAA, ATM.

FundingNo financial support.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interests.