Dengue infection and its associated complication contributes to a significant number of deaths as per World Health Organization (WHO) statistics. The aim of the study is to identify Predictors associated with mortality in Dengue infection.

Materials and methodsIn this prospective observational study conducted at the tertiary care hospitals of north India from August 2023 to December 2024, confirmed cases of dengue fever with a duration of less than seven days were recruited. Patients classified into Survivors or non-survivors, variables that were found to have statistically significant associations on univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis by logistic regression by enter method for predictors of dengue mortality.

ResultsA total of 158 dengue patients were recruited of which 18 (11.4%) died from the disease. Altered mental status, dyspnea at rest, and decreased urine output were significantly more frequent among non-survivors. Regarding laboratory parameters, non-survivor group exhibited significantly elevated levels of total leukocyte count, urea, creatinine, liver enzymes and International normalized ratio. Application of logistic regression using 3 factors-qSOFA (quick sequential organ failure assessment), creatinine and ferritin were performed which showed a statistically significant association with creatinine and ferritin. Odd Ratio (OR) for creatinine 1.449 indicates that for every unit increase in creatinine, the odds of mortality increase by 44.9%. Although the OR is exactly 1, the tight CI around 1 suggests that elevated ferritin is associated with mortality, but with a small effect size (p – 0.047).

ConclusionsThe presence of raised creatinine and elevated serum ferritin were predictors associated with a higher risk of mortality.

La infección por dengue y sus complicaciones asociadas contribuyen a un número significativo de muertes, según las estadísticas de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). El objetivo del estudio es identificar los predictores asociados con la mortalidad en la infección por dengue.

Materiales y métodosEn este estudio observacional prospectivo, realizado en hospitales de atención terciaria del norte de la India entre agosto de 2023 y diciembre de 2024, se reclutaron casos confirmados de dengue con una duración inferior a siete días. Los pacientes, clasificados como sobrevivientes y no sobrevivientes, se sometieron a un análisis multivariante mediante regresión logística por el método de entrada para los predictores de mortalidad por dengue.

ResultadosSe reclutaron 158 pacientes con dengue, de los cuales 18 (11,4%) fallecieron a causa de la enfermedad. La alteración del estado mental, la disnea en reposo y la disminución de la diuresis fueron significativamente más frecuentes entre los no supervivientes. En cuanto a los parámetros de laboratorio, el grupo de no supervivientes presentó niveles significativamente elevados de recuento total de leucocitos, urea, creatinina, enzimas hepáticas y razón internacional normalizada (IRN). Se realizó una regresión logística con 3 factores: qSOFA (evaluación secuencial rápida de fallo orgánico), creatinina y ferritina, que mostró una asociación estadísticamente significativa. Un OR (odd ratio) para la creatinina de 1449 indica que por cada unidad de aumento de creatinina, la probabilidad de mortalidad aumenta un 44,9%. Aunque el OR es exactamente 1, el IC estrecho en torno a 1 sugiere que la ferritina elevada se asocia con la mortalidad, pero con un tamaño del efecto pequeño (p – 0,047).

ConclusionesLa presencia de niveles elevados de creatinina y ferritina sérica fueron predictores asociados con un mayor riesgo de mortalidad.

Dengue is spreading at an alarming rate, with cases reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) increasing from 505,430 in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019.1 Many dengue infections are either asymptomatic or manifest as mild febrile illnesses that resolve spontaneously, leading to significant underreporting.2 Climate change is expected to exacerbate the global dengue burden. WHO estimates suggest that by the end of this century, an additional 4.7 billion people could be at risk of dengue worldwide.1,3

India is already experiencing the growing impact of dengue, with reported cases rising sharply from 28,066 in 2010 to 289,235 in 2023.4 During peak transmission seasons, healthcare facilities are often overwhelmed by the volume of patients. A study by Donald S. Shepard et al. in 2014 estimated the annual direct medical cost of dengue treatment in India to be approximately US$548 million. This figure would increase substantially when accounting for underreporting, vector control, and surveillance expenses.4

While the mortality rate for dengue fever is typically less than 1%, it can rise to 2–5% in cases of severe dengue, even with proper medical care. In the absence of adequate healthcare, mortality rates can soar up to 20%.5 Thus, early identification of patients at higher risk of mortality is crucial for timely and effective medical intervention.

Despite various studies, research aimed at identifying reliable predictors of dengue-related complications and mortality remains limited. Existing studies have proposed numerous demographic, clinical, laboratory, and radiological markers as potential predictors of severity and fatality.6–8 For example, a study from South India identified the following risk factors for mortality: age over 40 years, hypotension, platelet count below 20,000 cells/mm3, elevated liver enzymes (ALT >200 U/L, AST > 200 U/L), increased prothrombin time, renal failure, encephalopathy, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and bleeding tendencies.9

However, the conclusions from these studies are often inconclusive due to limitations in study design or small sample sizes. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the clinical and laboratory parameters associated with mortality among patients admitted with dengue infection.

MethodologyThis was a single-center prospective observational study conducted to identify predictors of mortality in patients with dengue infection. The study took place at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, a 2250-bed referral hospital, from August 2023 to December 2024. The total study duration was approximately 17 months, encompassing two post-monsoon cycles, which typically correspond to peak dengue incidence in India.

Inclusion criteria were: patients aged 12 years and above, presentation to the hospital within seven days of symptom onset, and a confirmed diagnosis of dengue based on the WHO 2009 guidelines.9 Exclusion criteria included patients with concurrent infections (e.g., malaria, scrub typhus, typhoid, leptospirosis, Japanese encephalitis), those with active malignancy, and individuals receiving immunosuppressive therapy. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of PGIMER, Chandigarh (Approval No: INT/IEC/2024/SPL-131).

All enrolled patients were followed throughout their hospital stay, and their final outcomes—discharge, death, or leaving against medical advice (LAMA)—were recorded. Patients were categorized into survivors and non-survivors. Clinical, demographic, and laboratory parameters were collected between days 5 and 7 of illness and analyzed using SPSS version 30.0.

The quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score was employed to evaluate its utility as a predictor of mortality in dengue infection. qSOFA includes three clinical criteria: altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale ≤14), systolic blood pressure ≤ 100 mmHg, and respiratory rate ≥ 22 breaths per minute. Each parameter scores one point, and a qSOFA score ≥ 2 suggests a higher risk of mortality and a potential need for ICU-level care. Although not a diagnostic tool, qSOFA serves as a rapid bedside screening method, particularly in non-ICU settings.10

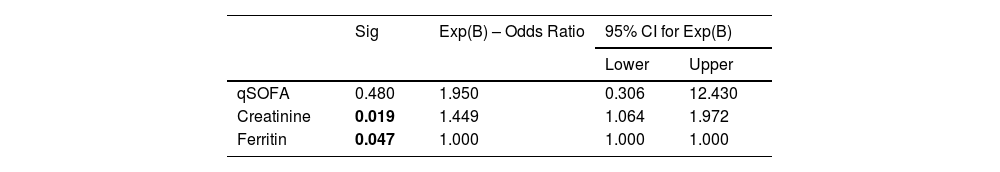

Variables analyzed included presenting symptoms, liver and renal function tests, and inflammatory markers. Univariate analysis was initially performed to identify parameters significantly associated with mortality. Variables with significant associations in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis using the enter method to determine independent predictors of mortality. Given the small sample size of non-survivors (n = 18), only three variables from the univariate analysis were selected for the regression model: qSOFA score, creatinine, and ferritin.

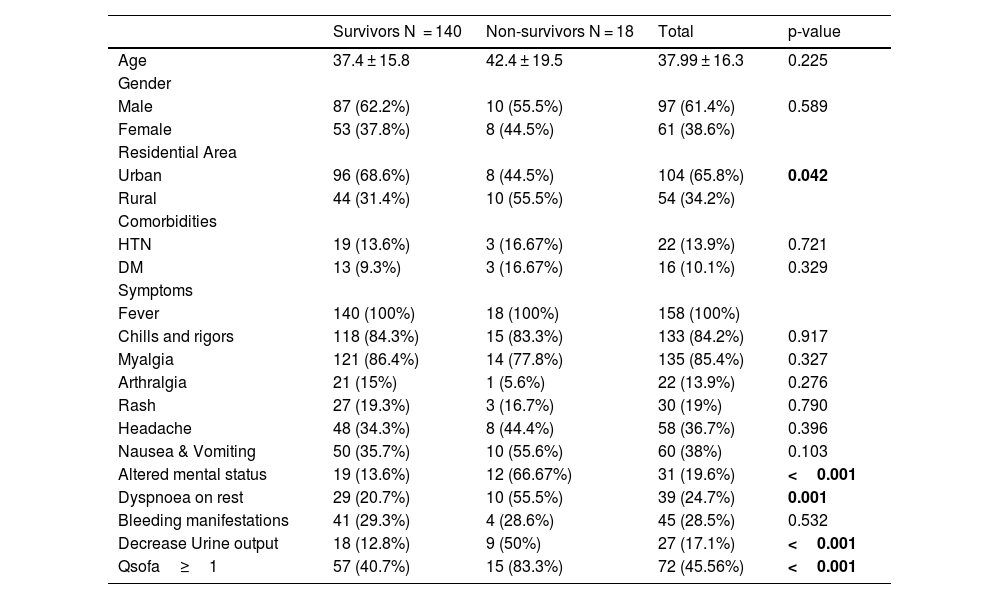

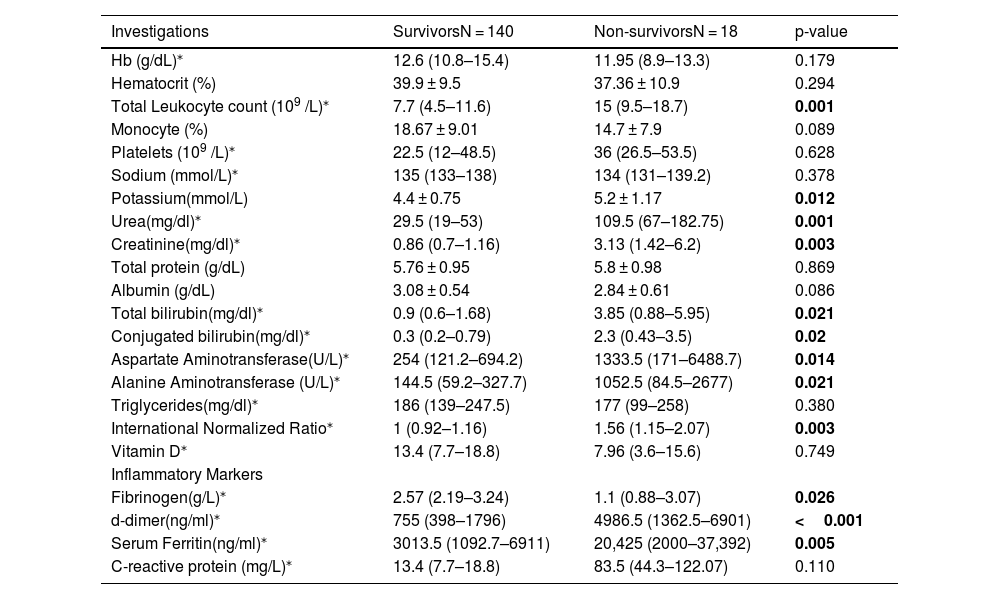

ResultA total of 158 dengue patients were recruited for the study, of which 18 (11.4%) died and 140 (88.6%) survived. Demographic analysis showed a higher proportion of male patients (61%) compared to females (39%). However, the mortality rate was higher among female patients (13%) than males (10%). The mean age of non-survivors was higher than that of survivors (42 years vs. 37 years), although this difference was not statistically significant. A greater proportion of non-survivors were from rural areas (55.5%) compared to urban areas (44.5%). In absolute terms, 8 of 104 urban patients (7.6%) and 10 of 54 rural patients (18.5%) died. Common comorbidities among non-survivors included hypertension (17%) and diabetes mellitus (17%), compared to 14% and 9% among survivors, respectively; however, these differences were not statistically significant. Among presenting symptoms, altered mental status (67% vs. 14%), dyspnea at rest (55.5% vs. 21%), and decreased urine output (50% vs. 13%) were significantly more common in non-survivors (Table 1). Laboratory findings indicated that non-survivors had significantly elevated levels of total leukocyte count (p = 0.001), urea (p = 0.001), creatinine (p = 0.003), liver enzymes AST and ALT (p = 0.014 and p = 0.021, respectively), and INR (p = 0.003). Median liver enzyme values in the non-survivor group exceeded 1000 IU/L, and bilirubin levels were elevated, meeting the WHO 2009 criteria for severe organ involvement.9 Inflammatory markers such as D-dimer, ferritin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were significantly higher in non-survivors. Notable differences were observed in D-dimer (p < 0.001) and ferritin (p = 0.005). Additionally, fibrinogen levels were significantly lower in non-survivors (p = 0.026) (Table 2).

Baseline Characteristics between Survivors and Non-survivors at time of admission.

| Survivors N = 140 | Non-survivors N = 18 | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.4 ± 15.8 | 42.4 ± 19.5 | 37.99 ± 16.3 | 0.225 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 87 (62.2%) | 10 (55.5%) | 97 (61.4%) | 0.589 |

| Female | 53 (37.8%) | 8 (44.5%) | 61 (38.6%) | |

| Residential Area | ||||

| Urban | 96 (68.6%) | 8 (44.5%) | 104 (65.8%) | 0.042 |

| Rural | 44 (31.4%) | 10 (55.5%) | 54 (34.2%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HTN | 19 (13.6%) | 3 (16.67%) | 22 (13.9%) | 0.721 |

| DM | 13 (9.3%) | 3 (16.67%) | 16 (10.1%) | 0.329 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 140 (100%) | 18 (100%) | 158 (100%) | |

| Chills and rigors | 118 (84.3%) | 15 (83.3%) | 133 (84.2%) | 0.917 |

| Myalgia | 121 (86.4%) | 14 (77.8%) | 135 (85.4%) | 0.327 |

| Arthralgia | 21 (15%) | 1 (5.6%) | 22 (13.9%) | 0.276 |

| Rash | 27 (19.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 30 (19%) | 0.790 |

| Headache | 48 (34.3%) | 8 (44.4%) | 58 (36.7%) | 0.396 |

| Nausea & Vomiting | 50 (35.7%) | 10 (55.6%) | 60 (38%) | 0.103 |

| Altered mental status | 19 (13.6%) | 12 (66.67%) | 31 (19.6%) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea on rest | 29 (20.7%) | 10 (55.5%) | 39 (24.7%) | 0.001 |

| Bleeding manifestations | 41 (29.3%) | 4 (28.6%) | 45 (28.5%) | 0.532 |

| Decrease Urine output | 18 (12.8%) | 9 (50%) | 27 (17.1%) | <0.001 |

| Qsofa≥1 | 57 (40.7%) | 15 (83.3%) | 72 (45.56%) | <0.001 |

Comparison of lab parameters between Survivors and Non-survivors.

| Investigations | SurvivorsN = 140 | Non-survivorsN = 18 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dL)⁎ | 12.6 (10.8–15.4) | 11.95 (8.9–13.3) | 0.179 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 39.9 ± 9.5 | 37.36 ± 10.9 | 0.294 |

| Total Leukocyte count (109 /L)⁎ | 7.7 (4.5–11.6) | 15 (9.5–18.7) | 0.001 |

| Monocyte (%) | 18.67 ± 9.01 | 14.7 ± 7.9 | 0.089 |

| Platelets (109 /L)⁎ | 22.5 (12–48.5) | 36 (26.5–53.5) | 0.628 |

| Sodium (mmol/L)⁎ | 135 (133–138) | 134 (131–139.2) | 0.378 |

| Potassium(mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 0.75 | 5.2 ± 1.17 | 0.012 |

| Urea(mg/dl)⁎ | 29.5 (19–53) | 109.5 (67–182.75) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine(mg/dl)⁎ | 0.86 (0.7–1.16) | 3.13 (1.42–6.2) | 0.003 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.76 ± 0.95 | 5.8 ± 0.98 | 0.869 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.08 ± 0.54 | 2.84 ± 0.61 | 0.086 |

| Total bilirubin(mg/dl)⁎ | 0.9 (0.6–1.68) | 3.85 (0.88–5.95) | 0.021 |

| Conjugated bilirubin(mg/dl)⁎ | 0.3 (0.2–0.79) | 2.3 (0.43–3.5) | 0.02 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase(U/L)⁎ | 254 (121.2–694.2) | 1333.5 (171–6488.7) | 0.014 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L)⁎ | 144.5 (59.2–327.7) | 1052.5 (84.5–2677) | 0.021 |

| Triglycerides(mg/dl)⁎ | 186 (139–247.5) | 177 (99–258) | 0.380 |

| International Normalized Ratio⁎ | 1 (0.92–1.16) | 1.56 (1.15–2.07) | 0.003 |

| Vitamin D⁎ | 13.4 (7.7–18.8) | 7.96 (3.6–15.6) | 0.749 |

| Inflammatory Markers | |||

| Fibrinogen(g/L)⁎ | 2.57 (2.19–3.24) | 1.1 (0.88–3.07) | 0.026 |

| d-dimer(ng/ml)⁎ | 755 (398–1796) | 4986.5 (1362.5–6901) | <0.001 |

| Serum Ferritin(ng/ml)⁎ | 3013.5 (1092.7–6911) | 20,425 (2000–37,392) | 0.005 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L)⁎ | 13.4 (7.7–18.8) | 83.5 (44.3–122.07) | 0.110 |

Despite these associations, none of the individual variables showed a statistically significant correlation with mortality in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Given the small number of non-survivors (n = 18), these results should be interpreted with caution. A focused logistic regression analysis including three variables—qSOFA score, creatinine, and ferritin—revealed that elevated creatinine and ferritin were significantly associated with mortality (Table 3). The odds ratio (OR) for creatinine was 1.449, indicating a 44.9% increase in mortality risk for each unit increase in creatinine. Although the OR for ferritin was 1, the narrow confidence interval around this value suggests a small but statistically significant association with mortality (p = 0.047). Elevated creatinine, indicative of acute kidney injury, was associated with an increased risk of death in patients hospitalized with dengue infection.

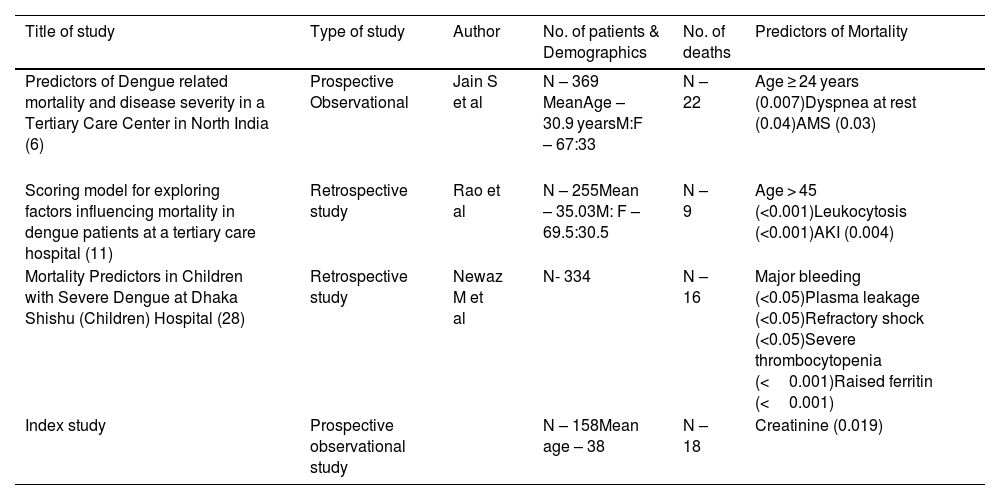

DiscussionMortality in dengue infection is multifactorial, often resulting from complications such as shock, organ failure, severe bleeding, or secondary infections. In this study, 18 deaths were recorded, all of which occurred among patients with severe dengue. Non-survivors had a higher mean age compared to survivors (42 vs. 37 years), though the difference was not statistically significant. Advanced age has been associated with increased mortality in other studies; for instance, a retrospective study from a tertiary care hospital in Mangalore, India, found that age over 45 years was an independent predictor of mortality.11 Rural patients had a mortality rate of 18.5%, compared to 7.6% among urban patients. Differences in care standards among referring hospitals may explain this disparity. Additionally, seroprevalence studies from India have shown that 53–72% of rural populations in the northern, western, and southern regions have evidence of dengue exposure, suggesting frequent transmission in these areas.12–14 The higher proportion of severe dengue cases in rural settings, combined with limited healthcare access, may account for the elevated mortality. This study found that non-survivors presented more frequently with altered mental status (AMS), dyspnea at rest, and decreased urine output (p < 0.001). A systematic review and meta-analysis identified altered mental status as a significant predictor of mortality in dengue, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.76 (95% CI: 1.67–8.42).15 Neurological involvement in dengue can result from direct central nervous system invasion, autoimmune reactions, toxic product release, or systemic complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, renal failure, electrolyte imbalance, or disseminated intravascular coagulation.16–18 A retrospective study in North India found dyspnea at presentation significantly associated with mortality (p < 0.001).19 A multicenter study in Bangladesh reported an OR of 2.87 (95% CI: 1.72–4.77) for severe dengue among patients with dyspnea. Dyspnea has been linked to shock, fluid overload, and pulmonary congestion, due to mechanisms such as capillary leakage, cardiogenic shock, hypoperfusion, and ARDS.20 In our study, a qSOFA score ≥ 1 was significantly associated with mortality, aligning with findings from W.A. Chang, who concluded that qSOFA is a useful mortality predictor in severe dengue.21 Non-survivors showed significantly higher levels of total leukocyte count (TLC), urea, creatinine, AST, ALT, bilirubin, and INR in univariate analysis, indicating systemic involvement. A study from Singapore similarly reported a higher risk of fatality with increased leukocyte counts (adjusted OR: 2.94).22 Elevated liver enzymes (AST/ALT ≥1000 IU/L), bilirubin, and deranged coagulation profiles were markers of severe hepatic involvement, which correlated with mortality. A meta-analysis found severe hepatitis associated with an OR of 29.222 (95% CI: 3.876–220.314) for mortality.15 Hepatitis typically occurs in the second week of dengue infection and is a common cause of death.23 Huang et al. also identified severe hepatitis as the strongest predictor of mortality among elderly dengue patients in Taiwan.24 Inflammatory markers such as D-dimer and serum ferritin were significantly elevated in non-survivors, suggesting coagulopathy and hyperinflammation as contributing factors. A study from central India reported mean D-dimer levels of 7566 ng/ml in severe dengue, compared to 621 ng/ml in dengue with warning signs, and 174 ng/ml in uncomplicated dengue.25 A systematic review highlighted a possible link between the activation of coagulation/fibrinolysis and adverse dengue outcomes, though more evaluation is needed.26 Given the small number of non-survivors (n = 18), caution is advised when interpreting the logistic regression findings. Nonetheless, elevated creatinine and ferritin emerged as significant predictors of mortality. Wang et al. reported a 22.4% fatality rate in patients with acute kidney injury (AKI), versus 11.6% overall in severe dengue. Their survival analysis also showed a significantly lower survival rate in AKI patients.27 Elevated serum ferritin also correlated with mortality in our study, in line with a 2024 study from Dhaka which identified high ferritin levels as a significant mortality predictor in children with severe dengue.28 Although the odds ratio for ferritin in our study was 1, the narrow confidence interval suggests a small but meaningful effect (Table 4).

Comparative analysis of earlier studies on predictors of Mortality in dengue infection.

| Title of study | Type of study | Author | No. of patients & Demographics | No. of deaths | Predictors of Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of Dengue related mortality and disease severity in a Tertiary Care Center in North India (6) | Prospective Observational | Jain S et al | N – 369 MeanAge – 30.9 yearsM:F – 67:33 | N –22 | Age ≥ 24 years (0.007)Dyspnea at rest (0.04)AMS (0.03) |

| Scoring model for exploring factors influencing mortality in dengue patients at a tertiary care hospital (11) | Retrospective study | Rao et al | N – 255Mean – 35.03M: F – 69.5:30.5 | N – 9 | Age > 45 (<0.001)Leukocytosis (<0.001)AKI (0.004) |

| Mortality Predictors in Children with Severe Dengue at Dhaka Shishu (Children) Hospital (28) | Retrospective study | Newaz M et al | N- 334 | N – 16 | Major bleeding (<0.05)Plasma leakage (<0.05)Refractory shock (<0.05)Severe thrombocytopenia (<0.001)Raised ferritin (<0.001) |

| Index study | Prospective observational study | N – 158Mean age – 38 | N – 18 | Creatinine (0.019) |

Due to its single-center design and small sample size, this study's generalizability is limited. Nonetheless, it highlights key clinical and laboratory parameters—such as AMS, oliguria, elevated creatinine, and ferritin—that can help identify high-risk patients early. Incorporating these markers into clinical protocols can improve triage, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately enhance patient outcomes in dengue management.

Author’s contributionDr. Parthraj Shenoy helped in data collection, Dr. Ashok Kumar Pannu did data analysis, Dr. Sourabh S. Sharda contributed in paper writing, Dr. Mandeep Bhatia helped in study design, Dr. Deba Parsad Dhibar helped in data collection and data analysis. Dr. Atul Saroch as the corresponding author contributed overall to the study design, data collection and data analysis.

Ethical approval statementThis study was approved by PGIMER Chandigarh Institutional Ethics Committee (Intramural) with No: INT/IEC/2024/SPL-131.

Funding sourceNone.

The authors whose names are listed certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers' bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

None.