Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosThe aim of this study is to detect human papilloma virus (HPV) especially types 16 and 18 through DNA expression from paraffin block preparations of cervical cancer and pre-cancer.

MethodsThis study was conducted at the Anatomical Pathology Laboratory and Molecular biology Hasanuddin University Medical Research Center (HUMRC) Laboratory. The samples that used were came from cervical specimens which had been processed into paraffin blocks and had been diagnosed as Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN) and Cervical carcinoma. HPV DNA was extracted from paraffin blocks using DNA extraction reagents from FFPE (Qiagen). DNA extraction products were then propagated by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. HPV genotyping is done by a reverse line blot method using Ampliquality HPV-Type Express (AB Analitica).

ResultsTotally 67 cervical samples from paraffin blocks preparations were diagnosed in Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) and Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN). The large number of cancer patients was more than 40 years old (42 patients/67.7%), with most of which are in the periods 41–50 years old (25 patients/40.3%). The most common cancer type was Non Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma (NK-SCC) with 50 (74.6%) samples. The most infectious strains are HPV strains 16, which were found in 53 (79.1%) samples both in single infection and co-infection with other HPV strains. Three of four HPV strains found were 16, 18 and 52 strains that belonging to High Risk strain of HPV, while strain 67 was included in the low risk group. There was also co-infection of 2 different HPV strains which involved 16 & 67 HPV Co-infection and 52 & 67 HPV Co-infection.

ConclusionCervical cancer patients were more commonly found in women with more than 30 years old, which the most common type was Non keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (NK-SCC). HPV infection is strongly associated with cervical cancer. HPV 16 infection was found in many cervical cancer lesions both as a single infection and co-infection with other types of low risk HPV.

Nowadays, non-communicable diseases which are quite worrying for the people especially for women are cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is ranked second most cause of death in women due to malignancy after breast cancer.1 The progression of this cancer is very slow. In the early stages of pre-cancer, it can actually be known by doing early detection of PAP smears.2 Human papilloma virus (HPV) is known to be the cause of cervical cancer.3 It can be transmitted through sexual contact, and involves infection with several types of viruses, and depends on personal hygiene. In Indonesia, there are 15,000 cases of cervical cancer every year. By 2030, the number of people with cervical cancer in Indonesia is expected to continue to increase by up to seven times.4

According to the annual report of non-communicable diseases, both for outpatient and inpatient cervical cancer in South Sulawesi in 2010, the highest number was found in Enrekang district as many as 127 cases, followed by Bone district with 83 cases and Makassar city in third place with 60 cases. Whereas in 2011, Enrekang district still ranked the highest as many as 25 cases followed by Makassar city as many as 18 cases.5 It shows that the prevention of cervical cancer in Makassar is still need improvement.

Based on the description above, it is necessary to perform a study on the detection of 40 HPV strains in paraffin blocks of cervical cancer tissue by using the multiple PCR and Reverse Line Blot methods. So that, it is expected to be able to answer some health problems, especially in diagnosing cervical cancer

MethodsThis study was conducted at the Anatomical Pathology Laboratory and Molecular biology Hasanuddin University Medical Research Center (HUMRC) Laboratory. The samples that used were came from cervical specimens which had been processed into paraffin blocks and had been diagnosed as Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN) and Cervical carcinoma.

HPV DNA was extracted from paraffin blocks using DNA extraction reagents from FFPE (Qiagen). Paraffin blocks were cut using microtome about 5-piece with a thickness of 10μm each which was then put into the eppendorf tube. The DNA extraction process methods according to the protocol listed in the instruction manual. DNA extraction products were then propagated by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method at a temperature of 95°C for 10min, 95°C for 30s, 50°C for 30s, 72°C 30s in 50 cycles, and 72°C for 5min in 1 cycle. HPV genotyping is done by a reverse line blot method using Ampliquality HPV- Type Express (AB Analitica) that can detect 40 HPV strains including high risk and low risk groups, including HPV strains 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68 (AEB), 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 81, 82, 83, 84, 87, 89 and 90.

ResultsThe selection of paraffin block samples is based on the role of HPV infection in causing cervical cancer, especially Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) through changes from pre-cancerous lesions, defined by Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN). Therefore, other cervical cancer samples such as Adenocarcinoma cervix were not included in this study, which in literature is less related to infection from HPV. From the evaluation, 67 samples of paraffin blocks were obtained which could be cut to extract DNA.

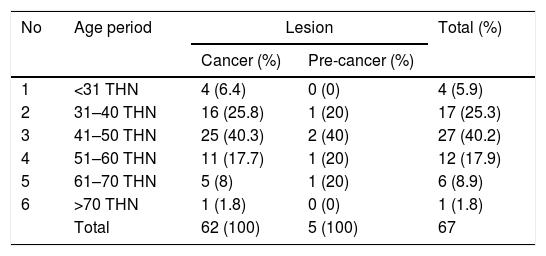

In Table 1, from 67 samples which obtained, the youngest age of the samples was 28 years old, while the oldest one was 71 years old, with an average age was 46.05 years old. Overall, the number of cervical cancer patients were increased with the increasing age. The large number of cancer patients was more than 40 years old (42 patients/67.7%), with most of which are in the periods 41–50 years old (25 patients/40.3%). As well as in pre-cancerous lesions, it was found more commonly in more than 40 years old (4 patients) and only one patient was found under 41 years old.

Sample distribution according to age.

| No | Age period | Lesion | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer (%) | Pre-cancer (%) | |||

| 1 | <31 THN | 4 (6.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.9) |

| 2 | 31–40 THN | 16 (25.8) | 1 (20) | 17 (25.3) |

| 3 | 41–50 THN | 25 (40.3) | 2 (40) | 27 (40.2) |

| 4 | 51–60 THN | 11 (17.7) | 1 (20) | 12 (17.9) |

| 5 | 61–70 THN | 5 (8) | 1 (20) | 6 (8.9) |

| 6 | >70 THN | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Total | 62 (100) | 5 (100) | 67 | |

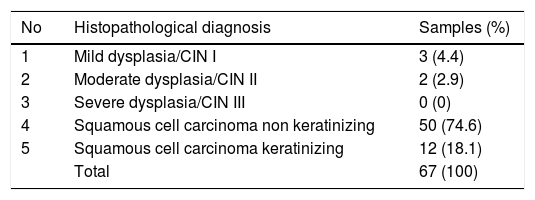

In Table 2, it was found that the most common cancer type was Non Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma (NK-SCC) with 50 (74.6%) samples. This cancer type is a very aggressive cancer compared to the Keratinizing SCC which microscopically, still resembles to normal squamous cells. However, the Non Keratinizing SCC type has a better prognosis than Keratinizing SCC because of its radio-and chemo-therapeutic responsiveness.

Sample distribution according to histopathological diagnosis.

| No | Histopathological diagnosis | Samples (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mild dysplasia/CIN I | 3 (4.4) |

| 2 | Moderate dysplasia/CIN II | 2 (2.9) |

| 3 | Severe dysplasia/CIN III | 0 (0) |

| 4 | Squamous cell carcinoma non keratinizing | 50 (74.6) |

| 5 | Squamous cell carcinoma keratinizing | 12 (18.1) |

| Total | 67 (100) |

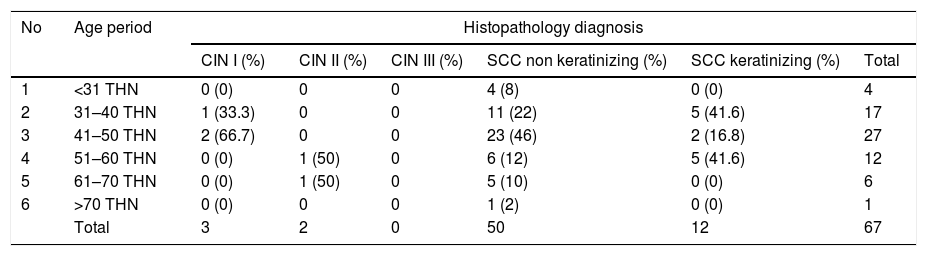

It was also found that pre-cancerous lesions of mild cervical cancer (CIN I) were found in younger patients compared to those with moderate category of pre-cervical cancer lesions (CIN II). There were no samples with severe category pre-cancerous lesions (CIN III) or also called Carcinoma In Situ, most likely the specimens had been found to have signs of invasion through the basal membrane, so that they could be categorized as Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), both keratinizing and non-keratinizing type (Table 3). From this table, it is also seen that NK-SCC was found in one period earlier compared to the K-SCC type. It also appears that more cases of the K-SCC are found over the age of 40 years, which is the menopause period. In this period, it is likely that the local body defense system in the genital area has decreased ability, in addition to the accumulation of genetic mutations that form the basis of Cervix cell transformation to becomes neoplastic cells.

Sample distribution according to histopathology diagnosis related to age.

| No | Age period | Histopathology diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIN I (%) | CIN II (%) | CIN III (%) | SCC non keratinizing (%) | SCC keratinizing (%) | Total | ||

| 1 | <31 THN | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 |

| 2 | 31–40 THN | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 11 (22) | 5 (41.6) | 17 |

| 3 | 41–50 THN | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 23 (46) | 2 (16.8) | 27 |

| 4 | 51–60 THN | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 | 6 (12) | 5 (41.6) | 12 |

| 5 | 61–70 THN | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 6 |

| 6 | >70 THN | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 2 | 0 | 50 | 12 | 67 | |

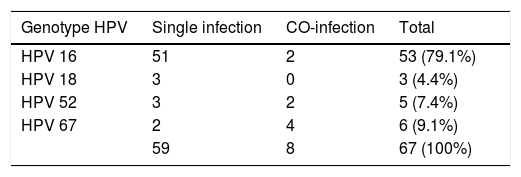

It was found that there were 4 strains of the HPV virus that infected patients who were the samples of this study (Table 4). The most infectious strains are HPV strains 16, which were found in 53 (79.1%) samples both in single infection and co-infection with other HPV strains. Of the four strains found, three of specimens were HPV strains 16, 18 and 52 that belonging to High Risk strain of HPV. The patients who infected with this strain group had a greater risk of developing cervical cancer. While the HPV strain 67 is included in the low risk group.

DiscussionCervical cancer in the precancerous or early stages does not cause symptoms. Abnormal bleeding from the vagina including bleeding spots is a common symptom of cervical cancer. It usually occurs after intercourse, outside of menstruation or after menopause.6 The diagnosis of cervical cancer can be made through several laboratory tests including Pap smear (cytology), Schiller Method which known as Visual inspection with acetic acid (IVA), and colposcopy examination.2 According to WHO, Cervical cancer is divided into Squamous cell carcinoma, Adenocarcinoma, Carcinoadenoskuamosa and Mesenchymal tumors.7 However, there are two forms that are often found, Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and Adenocarcinoma. By making the diagnosis as early as possible and starting the appropriate treatment, better results will be obtained so that the mortality rate from cervical cancer can be reduced.2

HPV is a pavovavirus DNA virus that can trigger genetic changes. This virus has a form of icosahedral with a size of 50–55nm, and has 72 capsomeres and 2 capsid proteins. HPV is a virus that is “non enveloped” and contains “double stranded DNA”.8 HPV infection in basal cells of the cervix goes through 2 phases, including Latent virus infection, where infection occurs from non-infectious viruses and Productive phases, where the formation of DNA from infectious viruses called virions. The formation of this viral DNA occurs in intermediate and superficial cells of squamous epithelial tissue. Virion then reproduces itself and has a damaging effect on cells, which can usually be detected cytologically and histopathologically.9 The HPV infects basal epithelial cells in the metaplasia area and the transformation zone of the cervix. After infecting the cervical epithelial cells, they will leave their genome sequences on the host cell. The HPV genome can be episomal in carcinoma in situ (CIN) or integrated with host DNA in invasive cancer.10

There are only 12 strains of HPV that are categorized as causes (carcinogens) of cervical cancer based on the Working Group of the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Where Group 1: carcinogens (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59), Group 2A: probable carcinogens (HPV68), Group 2B: possible carcinogens (HPV 26, 30, 34, 53, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 82, 85, and 97), and Group 3: not classified as to its carcinogenicity to humans (HPV 6 and 11).

In this study there was co-infection of 2 different HPV strains in the specimens, which involved Co-infection of HPV 16 & 67 and Co-infection of HPV 52 & 67. It appears to be a combination of high risk and low risk HPV strains. Most of the specimens examined were derived from a single infection of one type of HPV. It was found mainly in the high risk group. It seems that, only one type of HPV is enough to make genetic changes (mutations) in the gene that lead to malignant transformation of normal cervical epithelial cells.

Most HPV types of low risk such as HPV 67 in this study were obtained in CIN I (3 specimens) and CIN II (2 specimens). A single infection of HPV 67 was found at CIN I (2 specimens), while those for co-infection were found to vary from CIN I (1 specimen), CIN (2 specimens) and SCC (1 specimen). Cervical Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (CIN) is a disorder in which morphological changes occur in squamousa cervix epithelial cells and are characterized by enlarged nucleus size, hyperchromasia and sometimes accompanied by prominent nucleoli. This cell changes can be caused by HPV infection, but do not meet the criteria of Cervical carcinoma which is characterized by invasion of the submucous area that passes through the basement membrane. In fact, the cell changes in CIN, mainly on CIN I can disappear and return to normal epithelial tissue after eradication of the HPV. However, CIN II and III can develop into cervical cancer. It can be said that these two CIN lesions are a pre-cancerous lesion. It appears in this study, that co-infection of low risk with high risk HPV is more commonly found in lesions such as CIN II, and even in cervical carcinoma specimens. Unfortunately, in this study we did not find CIN III specimens. We estimate that the genotyping results in these lesions will not be too different from other advanced lesions such as CIN II and cervical cancer. For this reason, it is hoped that in future studies we can look for cervical specimens diagnosed as CIN III. However, the fact that advanced lesions such as CIN II and some cervical cancer specimens are found to be co-infected, will raise awareness that co-infection in cervical lesions can increase the risk of cervical cancer.

ConclusionCervical cancer patients were more commonly found in women with more than 30 years old, which the most common type was Non keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (NK-SCC). HPV infection is strongly associated with cervical cancer. HPV 16 infection was found in many cervical cancer lesions both as a single infection and co-infection with other types of low risk HPV.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study was supported by Hasanuddin University grant in accordance with the Implementation Agreement Research No. 15167/UN4.3.2/LK.23/2017 and 3617/UN4.21/LK.23/2017.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.