Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosThis study aimed to assess autonomic dysregulation by measuring Heart Rate Variability (HRV) parameters in acute ischemic stroke patients with insomnia.

MethodsThis was a descriptive observational study on 5 participants (4 females and one male) with acute ischemic stroke and insomnia. All participants were assessed through the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and then tested using a Polar H10 device for 5min recording during night sleep. The collected data analyzed by Kubios HRV Analysis Software 3.2 (MATLAB, Kuopio, Finland).

ResultsThis study showed that all participants (age 51.2±12.61) had subthreshold to moderate insomnia based on ISI (14.8±2.48) and had poor sleep quality based on PSQI (16.4±3.72). There was an increase of mean heart rate (HR) (81.8±13.86), root mean square of successive differences (rMSSD) (46.6±38.05), and sympathetic nervous system index (SNS Index) (1.542±1.567), as well as the decrease of standard deviation of normal-normal interval (SDNN) (37.8±20.53), low frequency (LF) (449.2±371.8), high frequency (HF) (812.6±773.8), LF/HF (1.89±1.72), and parasympathetic nervous system index (PNS Index) (−0.462±1.210).

ConclusionsThe Analysis of HRV showed an autonomic dysregulation in the form of parasympathetic dysfunction and sympathetic hyperactivation during night sleep in the acute phase of ischemic stroke with insomnia.

Sleep is a complex physiological process. Research proved physiological changes during sleep that involves the central nervous system, the autonomic, neuromuscular, respiratory, nervous system, cardiovascular system, endocrine system, gastrointestinal tract, thermoregulatory systems, and immunoregulators. The autonomic nervous system plays a crucial role in sleep, which controls cardiovascular function, respiration, motility, and gastrointestinal secretions. Changes in the autonomic base during sleep include increased parasympathetic tone and decreased sympathetic activity during NREM sleep. More increase in parasympathetic activity and a decrease in sympathetic activity mark the REM phase. However, in this phase, there are also changes in intermittent sympathetic activity, causing arrhythmias.1

Autonomic function disorders often occur in ischemic stroke patients and are associated with poor outcomes. Autonomic disorders can also occur in sleep disorders, such as sleep disorder and insomnia, and are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.2–4

Heart Rate Variability Analysis (HRV) is a method that is widely recognized and used to measure autonomic nerve activity. HRV is the measurement and recording of the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats. There are two kinds of HRV analysis approaches, namely linear and non-linear. The linear analysis uses the time domain and frequency domain. Time-domain variables include the standard deviation of normal to normal intervals (SDNN), root mean square of successive difference (rMSSD). Frequency domain variables include very-low-frequency (VLF), low-frequency (LF), high-frequency (HF), and LF/HF ratio. A non-linear analysis is the latest method, using parameters such as approximate entropy (APEN), multiscale entropy (MSE), and Detrended fluctuations (DFA).5,6

MethodsResearch locationThe research was conducted in Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital, Makassar, and was carried out for a month, May 2019. The samples used in this study were acute ischemic stroke patients suffering from insomnia. The samples were five patients selected by consecutively and met these following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

The inclusion criteria of this study were acute ischemic stroke based on clinical manifestations and radiological imaging results, suffering from insomnia, aged 18–65 years old, and willing to be included in this study by signing informed consent. Patient with hemorrhagic stroke, unconscious, mental disorders (depression, anxiety), cognitive impairment, severe systemic diseases (lungs, impaired kidney function, metastases), myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, carotid stenting, moderate-severe valvular dysfunction, dyspnea, asthma, consuming alcohol, stimulants (caffeine), sedatives, beta-blocker drugs, hyperpyrexia (>37.5°C), and severe hypertension (systolic≥220, diastolic≥120).

Type and source of dataThe data to be measured were related to the demographic data, sleep score (PSQI and, ISI) and HRV parameters. The data were obtained from the patient's history, physical examination, neuroimaging, PSQI questionnaire, ISI questionnaire, and the analysis of HRV.

Data collection techniquesAcute ischemic stroke patients given the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire to determine whether they had sleep disorders, types of sleep disorders and sleep quality. After that, the sample was scored by the Insomnia Severity Scale (ISI) questionnaire to determine how severe the degree of insomnia suffered. Measurement of HRV for 5min using a Polar H10 when the patient is sleeping. The collected data were then analyzed with Kubios HRV Analysis Software 3.2 (MATLAB, Kuopio, Finland). Data analysis uses linear time domain and frequency domain measurements.

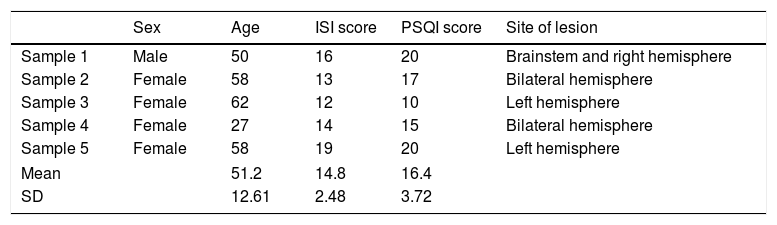

ResultsBased on Table 1, it was obtained consisting of 1 sample of males and four samples of the female. When viewed from age, the youngest was sample 4 at aged 27 years, the oldest was sample 3 aged 62 years, while the mean was 51.2±12.6 years; the lowest ISI score is 12, the highest is 19, the mean is 14.8±2.48; the highest PSQI score was 20, the lowest was 10, the mean was 16.4±3.72; the location of the lesions i.e., bilateral hemispheres two samples, hemisphere two samples, and pons lesions and one sample on the right hemisphere.

Demography characteristic.

| Sex | Age | ISI score | PSQI score | Site of lesion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Male | 50 | 16 | 20 | Brainstem and right hemisphere |

| Sample 2 | Female | 58 | 13 | 17 | Bilateral hemisphere |

| Sample 3 | Female | 62 | 12 | 10 | Left hemisphere |

| Sample 4 | Female | 27 | 14 | 15 | Bilateral hemisphere |

| Sample 5 | Female | 58 | 19 | 20 | Left hemisphere |

| Mean | 51.2 | 14.8 | 16.4 | ||

| SD | 12.61 | 2.48 | 3.72 | ||

ISI, Insomnia Severity Score; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

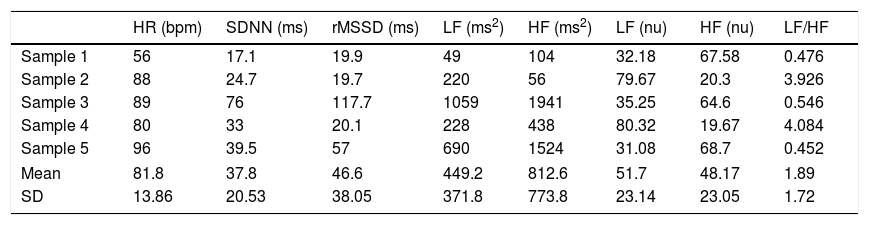

Table 2 shows the HRV parameters according to the time and frequency domain. The time domain is Heart Rate (HR), the standard deviation of normal–normal intervals (SDNN), root mean square of successive differences (rMSSD). Frequency domains are low frequency (LF), high frequency (HF), and LF/HF ratio.

HRV parameters at night.

| HR (bpm) | SDNN (ms) | rMSSD (ms) | LF (ms2) | HF (ms2) | LF (nu) | HF (nu) | LF/HF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 56 | 17.1 | 19.9 | 49 | 104 | 32.18 | 67.58 | 0.476 |

| Sample 2 | 88 | 24.7 | 19.7 | 220 | 56 | 79.67 | 20.3 | 3.926 |

| Sample 3 | 89 | 76 | 117.7 | 1059 | 1941 | 35.25 | 64.6 | 0.546 |

| Sample 4 | 80 | 33 | 20.1 | 228 | 438 | 80.32 | 19.67 | 4.084 |

| Sample 5 | 96 | 39.5 | 57 | 690 | 1524 | 31.08 | 68.7 | 0.452 |

| Mean | 81.8 | 37.8 | 46.6 | 449.2 | 812.6 | 51.7 | 48.17 | 1.89 |

| SD | 13.86 | 20.53 | 38.05 | 371.8 | 773.8 | 23.14 | 23.05 | 1.72 |

HR, heart rate; SDNN, standard deviation of normal-normal interval; rMSSD, root mean square of successive differences; LF, low frequency; HF, high frequency; bpm, beat perminute; ms, millisecond; ms2, milisecondsquare; nu, normalized unit.

Based on HR parameters, the highest value is 96bpm, the lowest is 56bpm, and the mean is 81.8±13.86bpm; The highest SDNN was 76ms, the lowest was 24.7ms, and the mean was 37.8±20.53ms; The highest rMSSD is 117.7ms, the lowest is 19.7ms, and the mean is 46.6±38.05ms.

Based on the LF parameter, the highest value is 1059 ms2, the lowest is 49ms2, and the mean is 449.2±371.8ms2; The highest HF was 1941ms2, the lowest was 56ms2, and the mean was 812.6±773.8ms2; The highest LF rate was 80.32, the lowest was 31.08, and the mean was 51.7±23.14; The highest HF was 68.7, the lowest was 19.67, and the mean was 48.17±23.05; The highest LF/HF was 4.084, the lowest was 0.452, and the mean was 1.89±1.72.

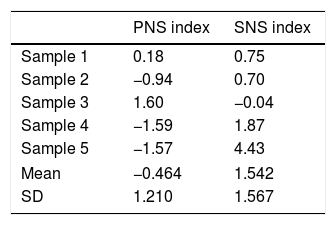

Based on Table 3, the highest Parasympathetic Nervous System Index (PNS Index) value is 1.60, the lowest is −1.59, and the mean is −0.449±1.210; The highest Sympathetic Nervous System Index (SNS Index) is 4.43, the lowest is −0.04, and the mean is 1.542±1.567.

DiscussionTable 1 shows that most samples are women; this is in accordance with research by Leppavuori (2010), which states that the frequency of insomnia in stroke patients is mostly women.7

Based on the PSQI score, it is shown that all samples had poor sleep quality. It is following research by Kim et al. (2016) which reported that in patients with acute ischemic stroke who experience sleep disorders having a high PSQI score indicates poor sleep quality.8

Under normal circumstances, when resting, there is usually a decrease in HR; this indicates parasympathetic activation. Research by Bonnet et al. (1998) and Zambotti et al. (2011) found a slight increase in HR in people with insomnia compared with the healthy population.4,9 While Bodapati et al. (2017) get HR values that are almost the same between stroke and non-stroke patients.10 The results of our study get a mean HR of 81.8±13.86, where this value is higher than the three studies. The increased HR value in this study reflects an increase in sympathetic activity compared to parasympathetic.

The SDNN value in this study is lower than the average value obtained by Nunan et al. (2010). Lower SDNN values were also found in people with insomnia (Spiegelhalder, 2010) and in patients with ischemic stroke.11–13 Both sympathetic and parasympathetic, both of which contribute to the value of SDNN. However, in the brief HRV recording at rest, the primary SDNN value comes from parasympathetic.6 The SDNN value in this study reflects a decrease in parasympathetic activity.

The mean value of rMSSD in this study was slightly higher than the normal value obtained by Nunan et al.12 However, apart from the mean value, three samples showed values below normal, 1 sample was normal, and 1 sample was above normal. Bodapati et al. (2017) found that rMSSD values in stroke patients were slightly lower than those without stroke, as well as Spiegelhalder (2010), who got rMSSD values in insomnia patients slightly lower than controls.10,11 The rMSSD parameter reflects variations in heart rate to the next heart rate and is used to measure changes in vagal activity. Thus, the majority of our sample showed decreased parasympathetic activity.

In this study, the mean value of LF was 449.2±371.8ms2. These results are lower than the normal values set by the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and The North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996) and the results of research by Nunan et al. (2010). Zambotti et al. (2013) get that LF values on people with insomnia are higher than controls. Whereas Chen et al. (2011) get lower LF values in patients with acute ischemic stroke.4,12,14,15 At rest, the LF parameter reflects baroreflex activity, which mainly comes from parasympathetic. Thus, the LF value in this study indicates a decrease in parasympathetic activity.

The mean HF value in this study was 812.6±773.8ms2 lower than the reference value by the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and The North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996). Zambotti et al. (2013) got more HF values higher in people with insomnia compared to controls, while Tian et al. (2018) get lower HF values in patients with acute ischemic stroke than controls.4,12,14,16 The HF parameter reflects parasympathetic activity. HF values can increase at night and decrease during the day. Low HF values are associated with stress, panic, anxiety, and anxiety.6 In this study, the decrease in HF values indicates a decrease in parasympathetic function.

A low LF/HF ratio reflects parasympathetic dominance, while a high LF/HF ratio indicates sympathetic dominance. Based on the research of Nunan et al. (2010) about the normal values of HRV parameters, then all of our samples are within the range of normal values. Research by Zambotti et al. (2013) found that the LF/HF ratio in people with insomnia was lower than in the normal population. Tian et al. (2018) also found a lower LF/HF ratio in patients with acute ischemic stroke than controls.4,12,16

In Table 3, the PNS Index is −0.464±1.210, and the SNS index value is 1.542±1.567. The decrease of PNS index below 0 and an increase in the value of the SNS index above 0, it reflects the dominance of the sympathetic. This is in accordance with the research conducted by Zambotti (2013), there is sympathetic hyperactivation that lasts throughout the night in patients with insomnia. Research by Xiongdkk (2013) also concluded that in ischemic stroke patients, parasympathetic dysfunction occurs.4,17–19

ConclusionsHRV analysis can determine autonomic dysregulation in patients with acute ischemic stroke who experience insomnia characterized by parasympathetic dysfunction and sympathetic hyperactivation during a sleepless night.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.