Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac arrhythmia that significantly impacts the cardiopulmonary function and quality of life of patients. Despite various treatment strategies, non-pharmacological interventions, particularly exercise interventions, have gained attention in recent years.

ObjectiveThrough systematic review and meta-analysis, this study explores the impact of physical activity on the exercise capacity and quality of life of AF patients. It assesses the safety, clinical outcomes, and physiological mechanisms of exercise intervention in the treatment of AF.

MethodsThe systematic review and individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis method were employed, following the PRISMA-IPD guidelines, for literature selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. The analysis focused on the impact of exercise on the cardiopulmonary function and quality of life of AF patients in randomized controlled trials.

ResultsA total of 12 randomized controlled trials involving 287 AF patients were included. Meta-analysis demonstrated a significant improvement in the 6-minute walk test capacity (SMD=87.87, 95% CI [42.23, 133.51]), static heart rate improvement (SMD=−7.63, 95% CI [−11.42, −3.85]), and cardiopulmonary function enhancement (SMD=2.37, 95% CI [0.96, 3.77]) due to exercise. There was also a significant improvement in the quality of life (SMD=0.720, 95% CI [0.038, 1.402]).

ConclusionExercise has a significant effect on improving exercise capacity and cardiopulmonary function in patients with atrial fibrillation. Particularly, high-intensity exercise training has a more significant impact on improving cardiopulmonary function and exercise capacity, emphasizing the importance of personalized exercise plans in enhancing the cardiopulmonary health of AF patients. Further research is needed to explore the effects of exercise on improving the quality of life in the future.

PROSPERO ID: CRD2023493917.

La fibrilación auricular (FA) es una arritmia cardíaca común que afecta significativamente la función cardiopulmonar y la calidad de vida de los pacientes. A pesar de diversas estrategias de tratamiento, las intervenciones no farmacológicas, en particular las intervenciones con ejercicio, han ganado atención en los últimos años.

ObjetivoA través de una revisión sistemática y un metaanálisis, este estudio explora el impacto de la actividad física sobre la capacidad de ejercicio y la calidad de vida de los pacientes con FA. Se evalúan la seguridad, los resultados clínicos y los mecanismos fisiológicos de la intervención con ejercicio en el tratamiento de la FA.

MétodosSe emplearon el método de revisión sistemática y metaanálisis de datos individuales de pacientes (IPD), siguiendo las guías PRISMA-IPD, para la selección de la literatura, la extracción de datos y la evaluación de la calidad. El análisis se centró en el impacto del ejercicio en la función cardiopulmonar y la calidad de vida de los pacientes con FA en ensayos controlados aleatorizados.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 12 ensayos controlados aleatorizados que involucraron a 287 pacientes con FA. El metaanálisis demostró una mejora significativa en la capacidad del test de caminata de 6 minutos (SMD=87,87, IC del 95% [42,23, 133,51]), mejora en la frecuencia cardíaca en reposo (SMD=−7,63, IC del 95% [−11,42, −3,85]) y mejora de la función cardiopulmonar (SMD=2,37, IC del 95% [0,96, 3,77]) debido al ejercicio. También se observó una mejora significativa en la calidad de vida (SMD=0,720, IC del 95% [0,038, 1,402]).

ConclusiónEl ejercicio tiene un efecto significativo en la mejora de la capacidad de ejercicio y la función cardiopulmonar en pacientes con FA. En particular, el entrenamiento de alta intensidad tiene un mayor impacto en la mejora de la función cardiopulmonar y la capacidad de ejercicio, enfatizando la importancia de los planes de ejercicio personalizados para mejorar la salud cardiopulmonar de los pacientes con FA. Se necesita más investigación para explorar los efectos del ejercicio en la mejora de la calidad de vida en el futuro.

ID de PROSPERO: CRD2023493917.

AF is a common cardiac arrhythmia classified into first diagnosis, paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent forms.1 Typical symptoms of AF patients include palpitations, dyspnea, fatigue, dizziness, and syncope, exhibiting significant individual variations.2 Compared to other diseases, AF patients are more prone to recurrence, and long-term symptoms such as palpitations and dyspnea can lead to decreased activity capacity and reduced quality of life.3 With the aging population, the incidence of AF is increasing year by year, leading to significant public health issues such as atrial remodeling, myocardial fibrosis, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.4 The World Health Organization predicts that the incidence of AF will triple in the next thirty years, termed the “atrial fibrillation epidemic.” It is estimated that by 2050, Asia will have over 70million AF patients.5

In terms of AF treatment, it is generally divided into two major strategies: surgical treatment, mainly including catheter ablation and maze surgery.6 Catheter ablation obstructs abnormal electrical signals by burning or freezing specific areas of the heart, while maze surgery redirects electrical signal pathways by cutting and suturing heart tissue, restoring normal rhythm.7 The main principles of pharmacological treatment for AF are controlling ventricular rate, protecting cardiac function, restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm, preventing thromboembolic events, and slowing atrial electrical and structural remodeling.8

Due to the complexity of the AF mechanism, various comorbidities in patients, and the limited improvement of these methods mainly on pathological symptoms, patients are often unwilling to accept pharmacological treatment.8 Therefore, non-pharmacological treatment methods are particularly important, such as dietary control, health management, physical therapy, and exercise rehabilitation. Among many non-pharmacological treatment methods, physical activity is one of the effective ways to improve AF patients.9 Regular exercise can not only effectively prevent the occurrence of AF but also alleviate symptoms in AF patients (such as improving cardiac function, reducing symptoms such as palpitations and dyspnea), and reduce related complications.10 In addition, regular exercise can enhance the overall health of patients, positively influencing mental health, and reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety.11

The effectiveness of exercise intervention for AF has been confirmed to a certain extent.12 Moderate physical activity has shown a positive role in controlling cardiovascular risk factors and reducing the risk of AF, but long-term endurance training may increase the risk of AF by increasing atrial size.13 A study showed that athletes engaged in long-term exercise had a higher incidence of AF than the general population.14 Although some studies have shown the benefits of physical exercise on the exercise capacity and cardiopulmonary adaptability of AF patients, there is currently a lack of support from large-scale randomized exercise training trials.15 Existing studies are mostly single-center trials, secondary analyses, and observational studies.16 Therefore, more high-quality research is needed in this field to establish the safety of exercise intervention in AF treatment, improvement of quality of life, clinical outcomes, and the impact of related physiological mechanisms.

In view of this, this study aims to explore in-depth the impact of physical activity on the exercise capacity and quality of life of AF patients through systematic review and meta-analysis. By providing more advanced evidence, the study aims to draw clear conclusions, explore the safety of exercise intervention in AF treatment, improvements in quality of life, clinical outcomes, and the role of relevant physiological mechanisms.

MethodsThis study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively assess the impact of exercise on the improvement of physical activity in patients with AF. Adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure the rigor and transparency of the research.17

To enhance the study's verifiability, we registered it on the PROSPERO international prospective systematic review registration platform with the registration ID: CRD2023493917.18

Information sources and search strategyTo ensure the comprehensiveness and systematic nature of literature retrieval, we employed a search strategy covering multiple databases, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Additionally, to ensure the inclusiveness of the literature, we traced relevant randomized controlled trial literature based on published reviews or meta-analyses.

The search strategy for this study adhered to the PICO framework, with “atrial fibrillation” defined as the patient population (P) and “exercise intervention” as the intervention (I). To ensure comprehensive coverage, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were employed to capture all relevant concepts. For atrial fibrillation, these terms encompassed a range of synonyms, including “persistent atrial fibrillation,” “paroxysmal atrial fibrillation,” and “familial atrial fibrillation.” Similarly, for physical activity, terms such as “aerobic exercise,” “isometric exercises,” and “exercise training” were incorporated. The search was designed to maximize precision and breadth, with no restrictions imposed on the control group, outcome measures, or types of studies. Boolean operators (AND) were used to combine terms, ensuring robust retrieval of relevant data. The search was restricted to English-language publications, focused exclusively on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and included studies published up to December 31, 2022. Detailed documentation of the search process, including search dates, databases used, the number of results retrieved, and manually screened reference lists, was maintained to ensure methodological rigor.

Eligibility criteria and study selectionInclusion criteria- a.

Study subjects: Patients with atrial fibrillation;

- b.

Intervention group: Patients with atrial fibrillation receiving exercise intervention;

- c.

Study type: Randomized controlled trial;

- d.

Language: English literature.

- a.

Animal experiments;

- b.

Meta-analyses, reviews, conference abstracts, pathology reports, letters, guidelines.

This study employed a two-stage selection process. Based on the predefined search strategy, relevant literature was retrieved from various databases. Titles, keywords, and abstracts of the downloaded literature were imported into Endnote X20 software to remove duplicates. Initial screening was conducted by reading the titles and abstracts of each article, making a preliminary judgment on whether it met the inclusion criteria. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria established for this study, studies that were obviously irrelevant or did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The second screening involved a full-text review of the selected literature to further assess its compliance with the inclusion criteria.

Data collection process and risk bias assessmentMSJ and XKW were responsible for extracting the pre- and post-test values from the full text. In cases where there were disputes over certain data points between MSJ and XKW, XH made the final judgment and decision. Initial screening of the literature, to determine articles that met the research criteria, was independently carried out by MSJ and XKW. The extracted information included author, publication year, country, intervention method (specific physical training methods), intervention duration (duration of each training session), intervention period, control group method, subject age, test indicators, mean outcome indicators (MEAN), and standard deviation (SD). MSJ and XKW independently completed data extraction and recording, and then cross-checked to ensure accuracy. Any inconsistencies or disputed data points were reviewed and decided upon by XH. The collected data were organized into tabular form for further analysis and comparison.

Extraction of MEAN and SD values for study indicators was used for the synthesis of effect size statistics. Author, publication year, intervention time, intervention period, subject age, intervention method, country, and control group method were extracted to complete the inclusion literature feature table.

In this study, we used a modified PEDro scale to assess the quality of randomized controlled trial literature.19 The PEDro scale is designed for a quick assessment of the quality of randomized clinical studies in the PEDro database. The total score on the PEDro scale is 11 points. According to our assessment criteria, studies with scores below 5 are considered to be of medium to low quality, while studies with scores of 5 or above are considered high quality.

Outcome assessment6-Minute walk test; Resting heart rate; Cardiopulmonary function; Quality of life.

Synthesis methodsIn this study, a heterogeneity test was conducted for each indicator to assess the variability between study results. The I2 statistic was used to measure the degree of this difference. When I2≥50%, a random-effects model was used for analysis. Conversely, if I2<50%, a fixed-effects model was used for analysis.20

The analysis was completed using Stata 15.1 software. Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) was used as the primary statistical indicator for combining inter-group mean differences, and weights were calculated. P<0.05 was considered the criterion for determining statistically significant differences. When P>0.05, there was no statistical significance.

All models in this study underwent sensitivity analysis to assess the stability of the combined effect size results. Publication bias was assessed using Egger's test, and if publication bias was present, trimming was performed to correct for publication bias.

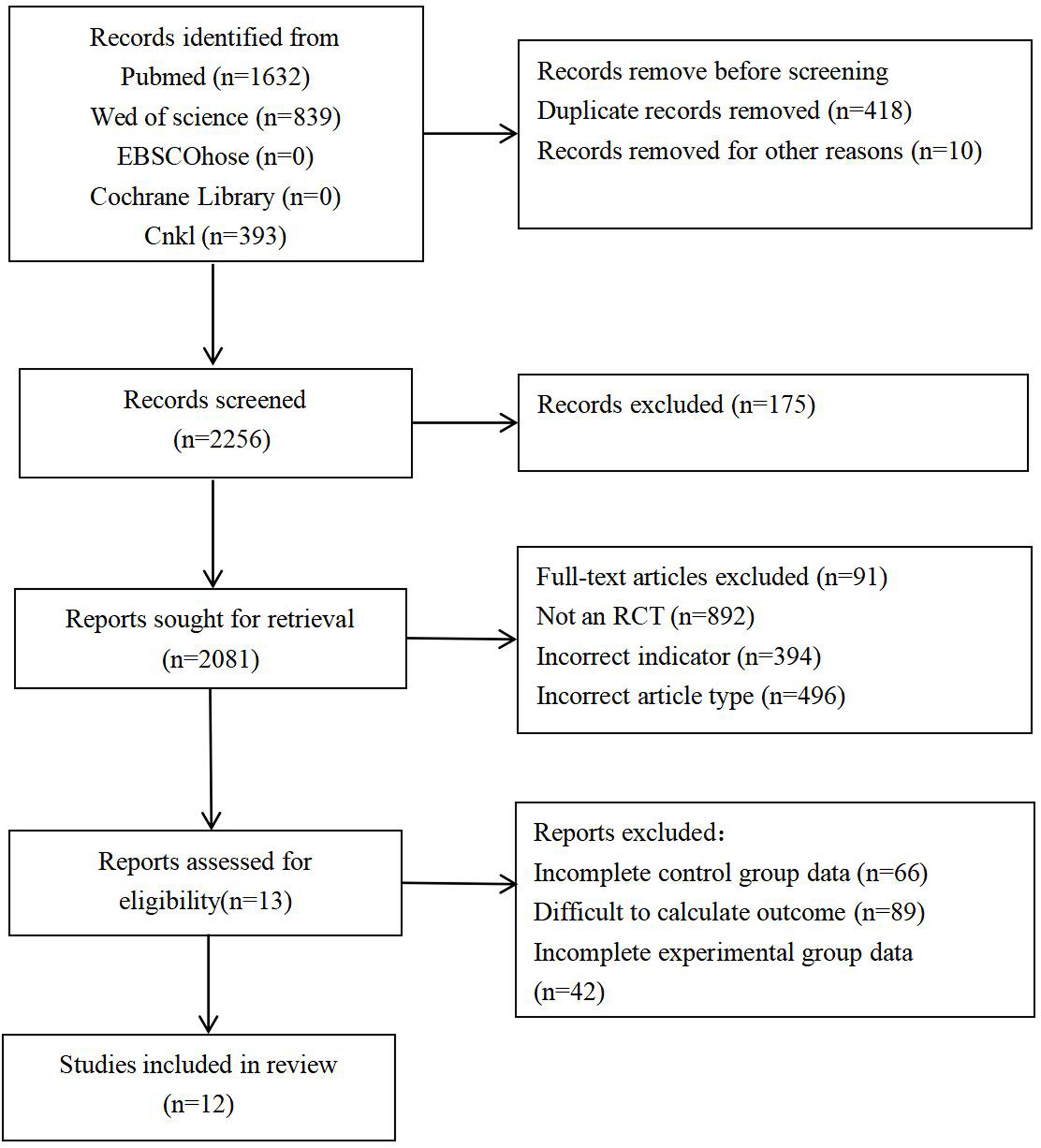

Research resultsStudy selection and characteristicsThe literature selection process in this study follows the systematic review and meta-analysis process outlined in the PRISMA statement. During the initial retrieval phase, a total of 3953 articles were retrieved from four electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost, and Cochrane Library. After removing duplicates and conducting preliminary and secondary screenings based on inclusion criteria, a total of 12 articles were finally included for systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1, literature search flowchart).

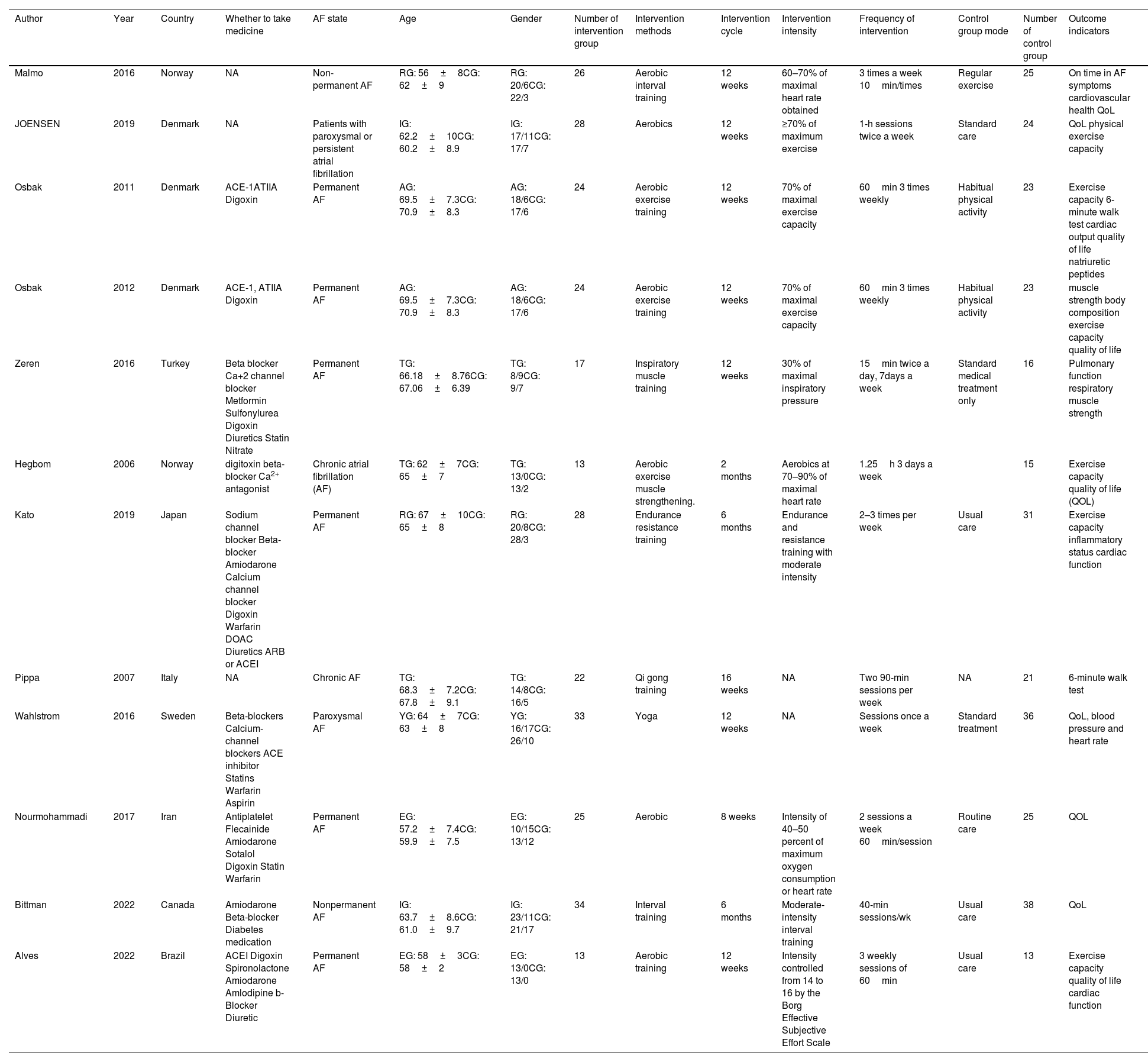

This study included 12 randomized controlled trials on exercise intervention for AF patients, encompassing research from multiple countries with a total of 287 participants. Geographically, three studies were published in Denmark, two in Norway, and one study from each of the remaining countries. Regarding the distribution of intervention periods, seven studies adopted a 12-week training period, two studies used 8 weeks and 16 weeks, respectively, and two studies extended to 24 weeks. The implemented intervention measures included aerobic exercise, resistance training, stretching exercises, and yoga. The covered categories of AF in the studies were diverse, including permanent AF, chronic AF, paroxysmal AF, and non-permanent AF. The detailed characteristics of each study are listed in the literature feature table (Table 1).

Table of included literature characteristics.

| Author | Year | Country | Whether to take medicine | AF state | Age | Gender | Number of intervention group | Intervention methods | Intervention cycle | Intervention intensity | Frequency of intervention | Control group mode | Number of control group | Outcome indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malmo | 2016 | Norway | NA | Non-permanent AF | RG: 56±8CG: 62±9 | RG: 20/6CG: 22/3 | 26 | Aerobic interval training | 12 weeks | 60–70% of maximal heart rate obtained | 3 times a week 10min/times | Regular exercise | 25 | On time in AF symptoms cardiovascular health QoL |

| JOENSEN | 2019 | Denmark | NA | Patients with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation | IG: 62.2±10CG: 60.2±8.9 | IG: 17/11CG: 17/7 | 28 | Aerobics | 12 weeks | ≥70% of maximum exercise | 1-h sessions twice a week | Standard care | 24 | QoL physical exercise capacity |

| Osbak | 2011 | Denmark | ACE-1ATIIA Digoxin | Permanent AF | AG: 69.5±7.3CG: 70.9±8.3 | AG: 18/6CG: 17/6 | 24 | Aerobic exercise training | 12 weeks | 70% of maximal exercise capacity | 60min 3 times weekly | Habitual physical activity | 23 | Exercise capacity 6-minute walk test cardiac output quality of life natriuretic peptides |

| Osbak | 2012 | Denmark | ACE-1, ATIIA Digoxin | Permanent AF | AG: 69.5±7.3CG: 70.9±8.3 | AG: 18/6CG: 17/6 | 24 | Aerobic exercise training | 12 weeks | 70% of maximal exercise capacity | 60min 3 times weekly | Habitual physical activity | 23 | muscle strength body composition exercise capacity quality of life |

| Zeren | 2016 | Turkey | Beta blocker Ca+2 channel blocker Metformin Sulfonylurea Digoxin Diuretics Statin Nitrate | Permanent AF | TG: 66.18±8.76CG: 67.06±6.39 | TG: 8/9CG: 9/7 | 17 | Inspiratory muscle training | 12 weeks | 30% of maximal inspiratory pressure | 15min twice a day, 7days a week | Standard medical treatment only | 16 | Pulmonary function respiratory muscle strength |

| Hegbom | 2006 | Norway | digitoxin beta-blocker Ca2+ antagonist | Chronic atrial fibrillation (AF) | TG: 62±7CG: 65±7 | TG: 13/0CG: 13/2 | 13 | Aerobic exercise muscle strengthening. | 2 months | Aerobics at 70–90% of maximal heart rate | 1.25h 3 days a week | 15 | Exercise capacity quality of life (QOL) | |

| Kato | 2019 | Japan | Sodium channel blocker Beta-blocker Amiodarone Calcium channel blocker Digoxin Warfarin DOAC Diuretics ARB or ACEI | Permanent AF | RG: 67±10CG: 65±8 | RG: 20/8CG: 28/3 | 28 | Endurance resistance training | 6 months | Endurance and resistance training with moderate intensity | 2–3 times per week | Usual care | 31 | Exercise capacity inflammatory status cardiac function |

| Pippa | 2007 | Italy | NA | Chronic AF | TG: 68.3±7.2CG: 67.8±9.1 | TG: 14/8CG: 16/5 | 22 | Qi gong training | 16 weeks | NA | Two 90-min sessions per week | NA | 21 | 6-minute walk test |

| Wahlstrom | 2016 | Sweden | Beta-blockers Calcium-channel blockers ACE inhibitor Statins Warfarin Aspirin | Paroxysmal AF | YG: 64±7CG: 63±8 | YG: 16/17CG: 26/10 | 33 | Yoga | 12 weeks | NA | Sessions once a week | Standard treatment | 36 | QoL, blood pressure and heart rate |

| Nourmohammadi | 2017 | Iran | Antiplatelet Flecainide Amiodarone Sotalol Digoxin Statin Warfarin | Permanent AF | EG: 57.2±7.4CG: 59.9±7.5 | EG: 10/15CG: 13/12 | 25 | Aerobic | 8 weeks | Intensity of 40–50 percent of maximum oxygen consumption or heart rate | 2 sessions a week 60min/session | Routine care | 25 | QOL |

| Bittman | 2022 | Canada | Amiodarone Beta-blocker Diabetes medication | Nonpermanent AF | IG: 63.7±8.6CG: 61.0±9.7 | IG: 23/11CG: 21/17 | 34 | Interval training | 6 months | Moderate-intensity interval training | 40-min sessions/wk | Usual care | 38 | QoL |

| Alves | 2022 | Brazil | ACEI Digoxin Spironolactone Amiodarone Amlodipine b-Blocker Diuretic | Permanent AF | EG: 58±3CG: 58±2 | EG: 13/0CG: 13/0 | 13 | Aerobic training | 12 weeks | Intensity controlled from 14 to 16 by the Borg Effective Subjective Effort Scale | 3 weekly sessions of 60min | Usual care | 13 | Exercise capacity quality of life cardiac function |

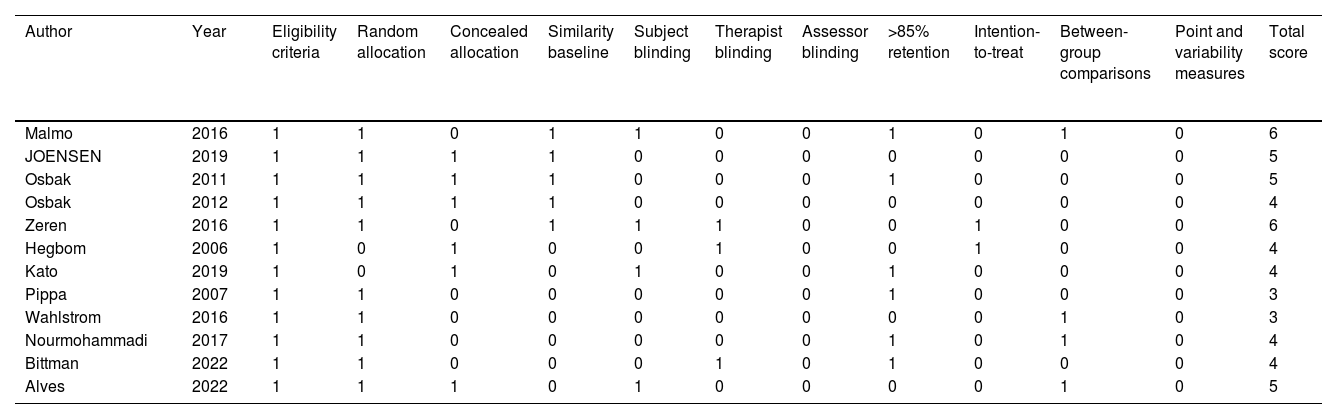

The methodological quality of the included literature in this study was generally moderate, with scores ranging from 3 to 6 out of a maximum score of 11. The studies by Malmo (2016) and Zeren (2016) received the highest scores, each with 6 points, indicating that these studies performed well in random allocation, baseline similarity, participant blinding, and retention rate. However, they showed shortcomings in therapist blinding, assessor blinding, and variability and validity measurements. JOENSEN (2019) and Osbak (2011) scored 5 points, meeting all criteria except blinding and intention-to-treat analysis. Other studies such as Osbak (2012), Hegbom (2006), and Kato (2019) scored 4 points, revealing deficiencies in participant blinding and retention rate. Pippa (2007) and Wahlstrom (2016) scored the lowest, with 3 points, not meeting several criteria, especially in baseline similarity, blinding, and variability measurements. Although all studies met eligibility and random allocation requirements, there were significant differences in other methodological quality aspects, potentially impacting the robustness of the study results (Table 2).

Literature quality evaluation.

| Author | Year | Eligibility criteria | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Similarity baseline | Subject blinding | Therapist blinding | Assessor blinding | >85% retention | Intention-to-treat | Between-group comparisons | Point and variability measures | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malmo | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| JOENSEN | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Osbak | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Osbak | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Zeren | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Hegbom | 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Kato | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Pippa | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Wahlstrom | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Nourmohammadi | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Bittman | 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Alves | 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

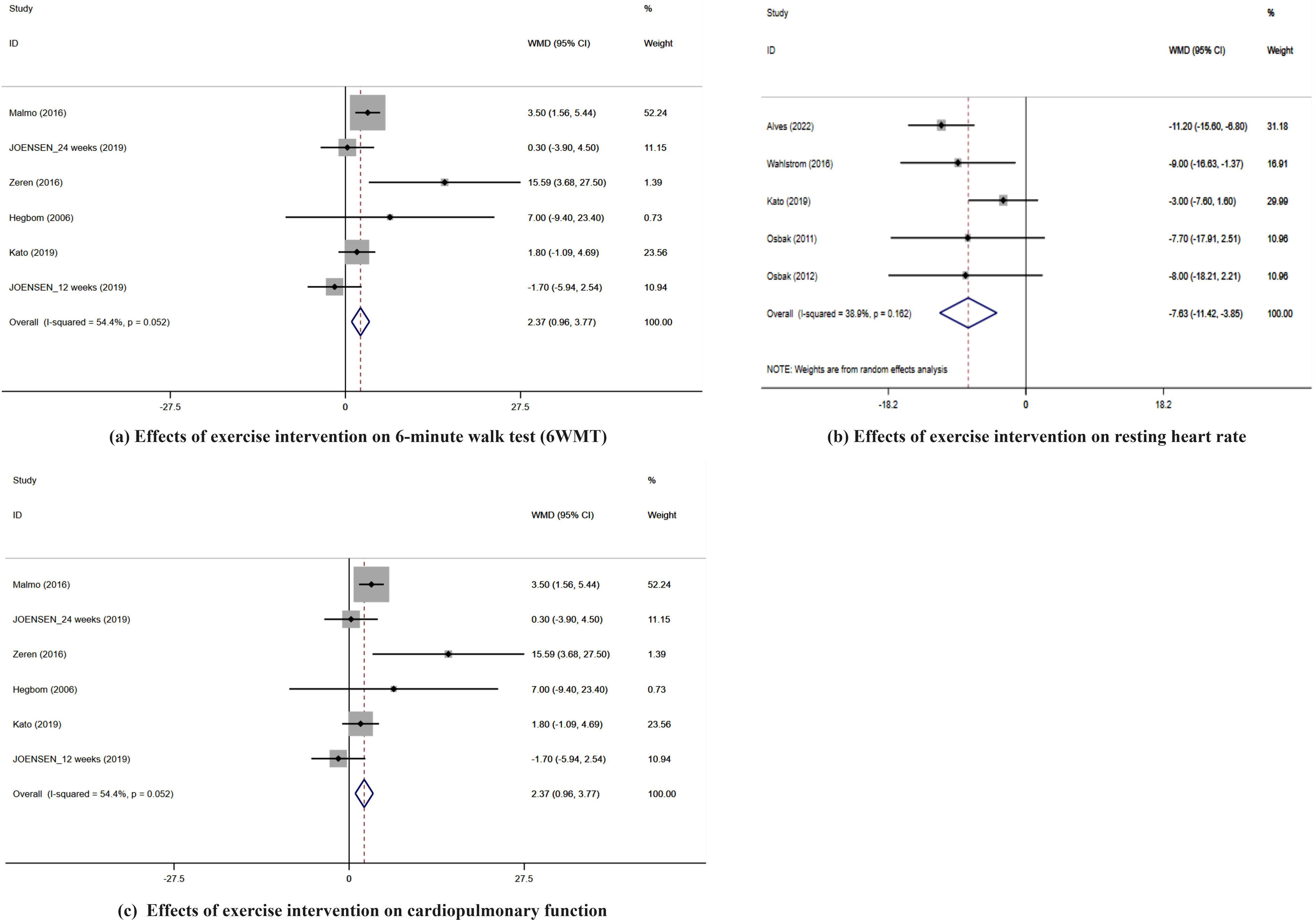

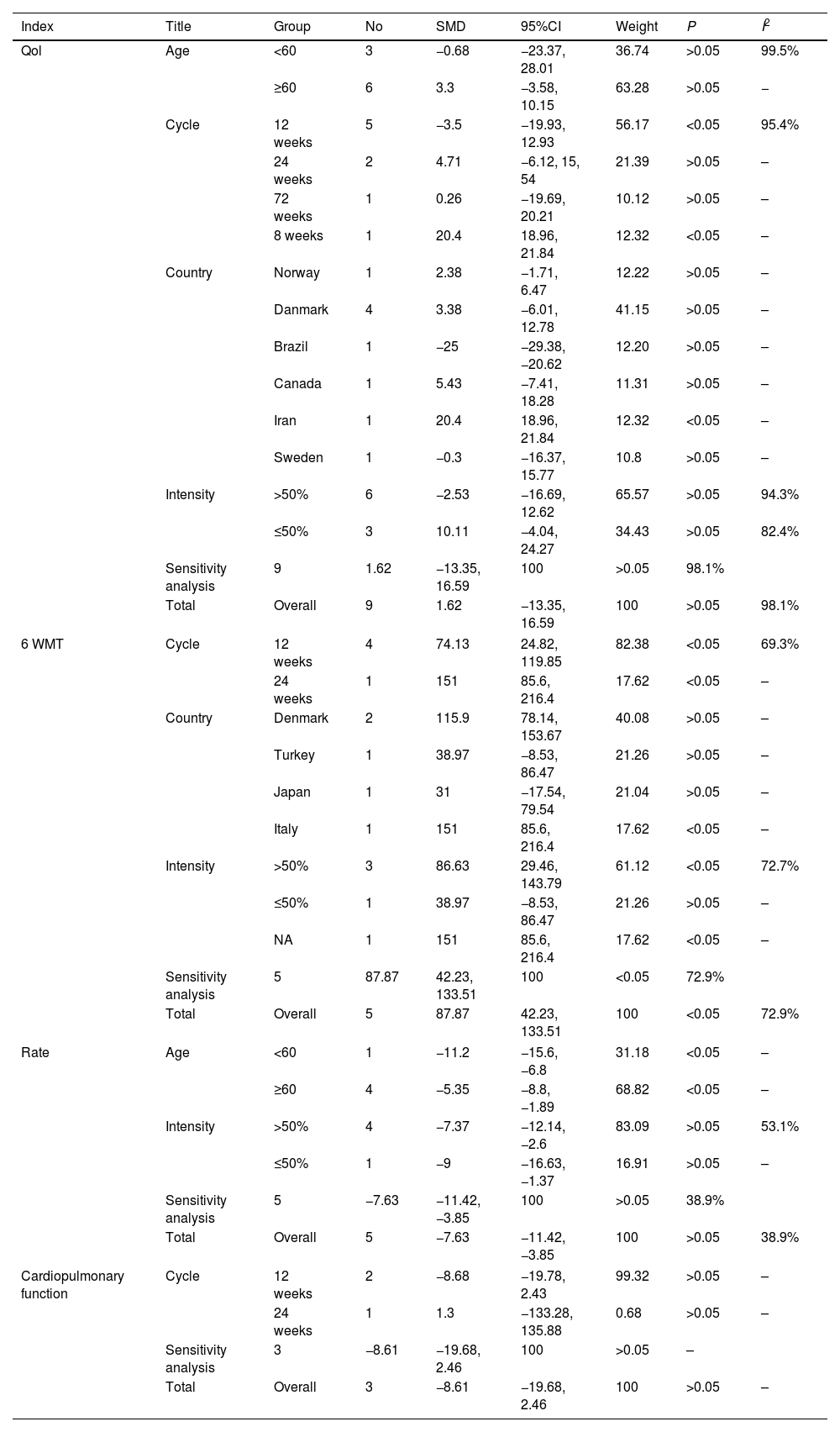

This indicator included a total of 5 studies, with an I2 of 72.9%, so a random-effects model was used. The analysis results showed a significant improvement in the 6-minute walk test ability for AF patients in the exercise group compared to the control group, with a significant effect size (SMD=87.87, 95% CI [42.23, 133.51], P<0.05) (Fig. 2). This indicates that exercise significantly enhances the walking ability of AF patients. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the results, SMD=87.87, 95% CI [42.23, 133.51].

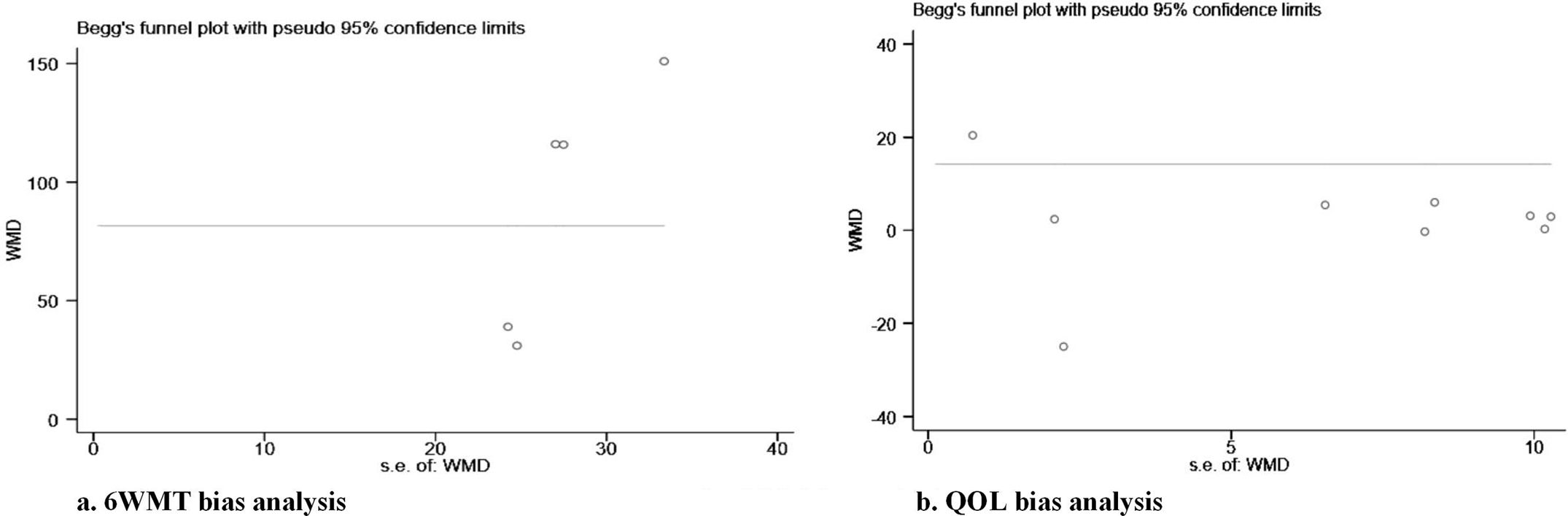

Intervention Period Subgroup Analysis included two subgroups of 12 weeks and 24 weeks. The combined effect size for the 12-week intervention was SMD=74.13, 95% CI [28.42, 119.85], P<0.05; for the 24-week intervention, the combined effect size was SMD=151, 95% CI [85.60, 216.40], P<0.05. Both subgroups showed positive effects, indicating that exercise can improve the 6-minute walk test results regardless of the intervention duration, and the longer the intervention time, the better the effect, as shown in Table 3. Exercise intensity subgroup analysis indicated that groups with intensity less than or equal to 50% showed no significant effect (P>0.05), while groups with intensity greater than 50% had a significant effect size (SMD=86.63, 95% CI [29.46, 143.79], P<0.05), suggesting that high-intensity exercise contributes to improving the 6-minute walk ability of AF patients. According to the country subgroup analysis, studies from Turkey and Japan showed no significant difference (P>0.05), while studies from Denmark and Italy had significant results, with SMDs of 115.90, 95% CI [78.14, 153.67] and SMD=151.00, 95% CI [85.60, 216.40], P<0.05 (Table 3). The publication bias analysis chart also shows a relatively stable state (Fig. 3).

Summary of subgroup analysis results.

| Index | Title | Group | No | SMD | 95%CI | Weight | P | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qol | Age | <60 | 3 | −0.68 | −23.37, 28.01 | 36.74 | >0.05 | 99.5% |

| ≥60 | 6 | 3.3 | −3.58, 10.15 | 63.28 | >0.05 | − | ||

| Cycle | 12 weeks | 5 | −3.5 | −19.93, 12.93 | 56.17 | <0.05 | 95.4% | |

| 24 weeks | 2 | 4.71 | −6.12, 15, 54 | 21.39 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 72 weeks | 1 | 0.26 | −19.69, 20.21 | 10.12 | >0.05 | – | ||

| 8 weeks | 1 | 20.4 | 18.96, 21.84 | 12.32 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Country | Norway | 1 | 2.38 | −1.71, 6.47 | 12.22 | >0.05 | – | |

| Danmark | 4 | 3.38 | −6.01, 12.78 | 41.15 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Brazil | 1 | −25 | −29.38, −20.62 | 12.20 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Canada | 1 | 5.43 | −7.41, 18.28 | 11.31 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Iran | 1 | 20.4 | 18.96, 21.84 | 12.32 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Sweden | 1 | −0.3 | −16.37, 15.77 | 10.8 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Intensity | >50% | 6 | −2.53 | −16.69, 12.62 | 65.57 | >0.05 | 94.3% | |

| ≤50% | 3 | 10.11 | −4.04, 24.27 | 34.43 | >0.05 | 82.4% | ||

| Sensitivity analysis | 9 | 1.62 | −13.35, 16.59 | 100 | >0.05 | 98.1% | ||

| Total | Overall | 9 | 1.62 | −13.35, 16.59 | 100 | >0.05 | 98.1% | |

| 6 WMT | Cycle | 12 weeks | 4 | 74.13 | 24.82, 119.85 | 82.38 | <0.05 | 69.3% |

| 24 weeks | 1 | 151 | 85.6, 216.4 | 17.62 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Country | Denmark | 2 | 115.9 | 78.14, 153.67 | 40.08 | >0.05 | – | |

| Turkey | 1 | 38.97 | −8.53, 86.47 | 21.26 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Japan | 1 | 31 | −17.54, 79.54 | 21.04 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Italy | 1 | 151 | 85.6, 216.4 | 17.62 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Intensity | >50% | 3 | 86.63 | 29.46, 143.79 | 61.12 | <0.05 | 72.7% | |

| ≤50% | 1 | 38.97 | −8.53, 86.47 | 21.26 | >0.05 | – | ||

| NA | 1 | 151 | 85.6, 216.4 | 17.62 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Sensitivity analysis | 5 | 87.87 | 42.23, 133.51 | 100 | <0.05 | 72.9% | ||

| Total | Overall | 5 | 87.87 | 42.23, 133.51 | 100 | <0.05 | 72.9% | |

| Rate | Age | <60 | 1 | −11.2 | −15.6, −6.8 | 31.18 | <0.05 | – |

| ≥60 | 4 | −5.35 | −8.8, −1.89 | 68.82 | <0.05 | – | ||

| Intensity | >50% | 4 | −7.37 | −12.14, −2.6 | 83.09 | >0.05 | 53.1% | |

| ≤50% | 1 | −9 | −16.63, −1.37 | 16.91 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Sensitivity analysis | 5 | −7.63 | −11.42, −3.85 | 100 | >0.05 | 38.9% | ||

| Total | Overall | 5 | −7.63 | −11.42, −3.85 | 100 | >0.05 | 38.9% | |

| Cardiopulmonary function | Cycle | 12 weeks | 2 | −8.68 | −19.78, 2.43 | 99.32 | >0.05 | – |

| 24 weeks | 1 | 1.3 | −133.28, 135.88 | 0.68 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Sensitivity analysis | 3 | −8.61 | −19.68, 2.46 | 100 | >0.05 | – | ||

| Total | Overall | 3 | −8.61 | −19.68, 2.46 | 100 | >0.05 | – | |

Resting heart rate included 5 studies, with heterogeneity of 38.9%, so a fixed-effects model was used. The results indicated a significant improvement in resting heart rate for AF patients in the exercise group compared to the control group (SMD=−7.63, 95% CI [−11.42, −3.85], P<0.05), as shown in Fig. 2. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the results.

Country subgroup analysis showed no significant improvement in Japan (P>0.05), while interventions in Brazil, Sweden, and Denmark were significant (SMD of −11.20, −9.00, and −7.63; P<0.05). Different exercise intensity subgroup analysis indicated that both intensity ≤50% and >50% significantly reduced resting heart rate (P<0.05). Age subgroup analysis found that regardless of average age<60 or ≥60 years, exercise effectively reduced resting heart rate (P<0.05). This suggests that AF patients in different age groups can benefit from exercise (Table 3).

Cardiopulmonary functionThe meta-analysis included a total of 5 studies, with heterogeneity of 54.4%, and a random-effects model was used. The analysis showed a significant improvement in cardiopulmonary function for AF patients in the exercise group compared to the control group (SMD=2.37, 95% CI [0.96, 3.77], P<0.05), as shown in Fig. 2. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the results (SMD=2.37, 95% CI [0.96, 3.77]).

Country subgroup analysis indicated no significant difference in results between Japan and Denmark (P>0.05), while interventions in Norway and Turkey were significant (SMDs of 3.55 and 15.59; 95% CI [1.62, 5.48] and [3.68, 27.50]). Age subgroup analysis results showed a significant intervention effect for the >60 years group (SMD=15.59, 95% CI [1.56, 5.44], P<0.05), and no significant effect for the <60 years group (P>0.05), indicating that exercise improves cardiopulmonary function in AF patients aged>60 years.

Quality of lifeIn this meta-analysis, a total of 10 studies were included. Heterogeneity was significant (I2=98.1%), so a random-effects model was used. The analysis results indicated a statistically significant improvement in the quality of life for AF patients through exercise, with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.720, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.038, 1.402], P<0.05.

Subgroup analysis based on average age divided into <60 years and 60 years and above showed no statistically significant improvement in both age groups (P>0.05). Exercise intensity subgroup analysis indicated that when intensity was less than 50%, SMD=2.42, 95% CI [0.008, 4.76], P<0.05, suggesting that low-intensity exercise significantly improved the quality of life; while for groups with intensity greater than 50%, the improvement effect was not significant (P>0.05). Subgroup analysis of different countries showed that, except for Ireland, the results from other countries were not statistically significant (P>0.05). The study from Ireland showed a significant improvement, with SMD=7.84, 95% CI [6.18, 9.50], P<0.05. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of the results, SMD=1.62, 95% CI [−13.35, 16.59]. Publication bias analysis suggested significant bias, especially in small-sample studies (Fig. 3).

DiscussionPatients with AF often experience various complications that significantly impact their quality of life.21 The compromised cardiac function resulting from AF affects cardiopulmonary function.22 Additionally, complications such as thrombosis in AF patients can lead to paralysis and physical disabilities, preventing them from engaging in physical activities and resulting in a decline in exercise capacity. The results of this meta-analysis demonstrate a significant impact of exercise on AF patients, with an effect size (SMD) of 87.87, 95% CI [42.23, 133.51], P<0.05. The exercise group showed a significant improvement in the exercise capacity of AF patients compared to the control group, especially with exercise intensity>50%, where the improvement in 6-minute walking ability was more pronounced. Furthermore, exercise significantly lowered the static heart rate of AF patients, improving symptoms of rapid heartbeat. The significant improvement effects were observed across different training intensities, periods, and age groups. Regarding cardiopulmonary function, the combined effect size after exercise was SMD=2.37, 95% CI [0.96, 3.77], P<0.05, indicating a significant improvement in cardiopulmonary function in AF patients through exercise, particularly impacting patients younger than 60 years.

This phenomenon may be attributed to the greater exercise tolerance and adaptability of younger patients.23 Their superior baseline cardiopulmonary function and robust physical recovery capacity enable them to safely engage in high-intensity exercise training,24 such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or prolonged aerobic exercise, both of which have been proven to significantly improve cardiopulmonary function. Younger patients also benefit from better cardiac and vascular elasticity,25 which facilitates mechanisms like cardiac remodeling during exercise, leading to enhanced cardiac output and more efficient oxygen transport and utilization, thereby resulting in marked improvements in cardiopulmonary function. Moreover, younger patients tend to demonstrate higher acceptance of structured and personalized exercise programs, with greater adherence and willingness to participate, which are critical for the effectiveness of interventions. In contrast, older patients often face limitations in training due to reduced cardiopulmonary reserve, myocardial fibrosis, or comorbidities, leading to diminished responsiveness to exercise.26 Psychological factors may also play a role, as younger patients are more likely to engage actively in exercise and maintain a positive mental state, further amplifying the benefits of exercise on cardiopulmonary function.27

The American Thoracic Society has developed detailed guidelines for the clinical application of the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), providing standardized procedures for its use in evaluating cardiopulmonary diseases.28 In recent years, both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology have recognized the 6MWT as a gold standard for assessing exercise capacity and included it as an evaluation indicator in heart failure diagnosis and treatment guidelines.29 The 6MWT, reflecting exercise capacity, is easily administered and widely accepted for its role in assessing cardiovascular health. Atrial fibrillation, characterized by reduced atrial contraction function leading to decreased ventricular ejection, results in compromised cardiopulmonary function.30 Increased heart rate can lead to chronic heart failure and other myocardial diseases, severely affecting cardiopulmonary function. This study, using peak oxygen consumption (VO2max) as an indicator,31 measured the cardiopulmonary coupling capacity under maximum exercise load, aiming to directly reflect changes in cardiopulmonary function. Monitoring static heart rate in AF patients is crucial for understanding their physiological status, providing insight into their rapid heartbeat status, and offering substantial support for symptom improvement.32

A substantial amount of past research has confirmed the beneficial effects of exercise on atrial fibrillation.33,34 Building upon existing research, this study further explores the general impact of exercise on AF patients across different training intensities and durations. Ortaga (2022) study confirmed the positive effects of regular moderate-intensity exercise on improving exercise tolerance in AF patients.35 This study specifically highlights a more significant improvement in the 6-minute walking test when exercise intensity exceeds 50%, providing a new perspective to this field. Additionally, our findings align with Moral et al.’s (2018) results,35 further confirming the influence of moderate-intensity exercise on exercise tolerance in AF patients. The study by Williams et al. (2020) also supports the benefits of exercise in enhancing the functional capacity of AF patients.36

Regarding improvements in cardiorespiratory function, Green et al.’s (2019) study found that aerobic exercise significantly improves the cardiovascular health of AF patients.37 Liu et al.’s (2021) studyemphasizes the importance of moderate exercise in improving cardiorespiratory function in AF patients, particularly evident in patients under 60 years old.38 Furthermore, Martin's (2020) study demonstrates that exercise effectively lowers the resting heart rate of AF patients and improves symptoms of rapid heartbeats.39 Brown (2022) study further confirms the effects of regular exercise on reducing resting heart rate and improving overall cardiac health in AF patients.40

This study further discovered that exercise training with an intensity exceeding 50% is more effective in improving the exercise capacity of AF patients.41 This may be attributed to the increased volume load on the heart during high-intensity exercise, leading to increased left ventricular volume, wall thickness, and end-diastolic volume.42 Consequently, this results in an increased stroke volume per beat. The elevation in stroke volume allows AF patients to achieve a lower heart rate while maintaining the same cardiac output, reducing the metabolic load on the heart.43 This creates a more effective time-pressure relationship, thereby more effectively improving the cardiorespiratory function and exercise capacity of patients.44

Patients with atrial fibrillation commonly face increased ventricular stiffness due to reduced myocardial compliance and impaired active relaxation capacity during the left ventricular diastolic period.45 This often leads to left ventricular filling disturbances, elevated end-diastolic pressure, and reduced stroke volume, subsequently decreasing cardiorespiratory function.46 Simultaneously, regular exercise training can increase heart rate in the short term, raising oxygen demand and inducing a temporary hypoxic state.47 This process stimulates the formation of local collateral circulation, achieving the so-called “biological bridging,” which improves myocardial perfusion, increases myocardial blood supply, and reduces damage to myocardial cells due to inadequate perfusion.48 As a result, these changes effectively improve cardiac function.

Sustained exercise, especially intermittent training, promotes blood circulation and activity in the respiratory system, stimulates skeletal muscle growth, increases the number of capillaries and muscles, thereby enhancing respiratory function and effectively improving lung function.49 Previous research indicates that after a period of exercise training, AF patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention show significant increases in oxygen uptake, oxygen pulse, and anaerobic threshold, while the maximum heart rate remains relatively unchanged.50 This suggests that improving coronary blood flow not only enhances cardiac function but also significantly strengthens cardiorespiratory function.51 During exercise, the contraction and relaxation functions of the heart are enhanced, vascular wall elasticity is increased, stroke volume is increased, allowing the cardiovascular system to transport oxygen more effectively and rapidly, enhancing overall endurance, and effectively improving cardiorespiratory function.52 Furthermore, by increasing cardiac output, improving left ventricular remodeling, improving end-diastolic volume, and reducing plasma neurohormone levels, exercise rehabilitation can also alter the histological characteristics of the myocardium. These combined effects ultimately achieve a significant improvement in cardiorespiratory function in AF patients.53

Consistent with past research, this study confirms the improvement in the quality of life for AF patients through exercise. Smith's (2019) study also supports the enhancement of life quality for AF patients through exercise.16 Regular exercise, by enhancing cardiac contraction and improving blood circulation efficiency, helps improve myocardial blood supply and alleviate the workload on the heart. This not only reduces the frequency of AF episodes but also alleviates symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea caused by AF, directly enhancing the quality of life.54 Simultaneously, regular exercise promotes the release of endorphins, a natural “pleasure chemical” that improves mood and reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety. This is particularly important for AF patients, as atrial fibrillation itself and the associated lifestyle restrictions often lead to increased psychological stress. Improving emotions through exercise significantly enhances the overall quality of life for patients.55

Regular exercise can enhance individuals’ self-efficacy and social interaction while reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. Exercise, as a positive lifestyle, not only improves patients’ physiological conditions but also enhances overall life satisfaction by promoting social participation and mental health.56 Moreover, during exercise, whether participating in group fitness classes or engaging in physical activities with friends or family, interpersonal relationships can be improved. For many atrial fibrillation patients, this social interaction serves as an important support system, providing emotional support and reducing feelings of loneliness, thereby enhancing the quality of life.57

The findings of this study further confirm these mechanisms, revealing the specific effects of exercise training on the improvement of exercise capacity and quality of life in atrial fibrillation patients. Through regular exercise interventions, significant improvements are observed in the myocardial and vascular functions of atrial fibrillation patients. This discovery provides empirical support for the exercise prescription for atrial fibrillation patients, emphasizing the importance of personalized exercise plans in improving cardiorespiratory health in this patient population.

This study provides valuable insights into the impact of exercise on AF patients; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. The overall quality of the included studies was moderate, which may affect the robustness of the findings. Additionally, the sample size was relatively small, comprising only 287 patients, potentially reducing the statistical power and limiting the reliability of subgroup analyses. Furthermore, significant heterogeneity was observed in some subgroup analyses, particularly regarding improvements in quality of life, with variations likely influenced by differences in cultural, social, and exercise habits across countries. Another limitation is the insufficient exploration of specific exercise intensities and frequencies; while subgroup analyses were conducted, clear guidance on optimal exercise protocols remains lacking. Future research should aim to address these limitations by conducting larger, high-quality randomized controlled trials and investigating the long-term effects of exercise interventions on cardiopulmonary function and quality of life, as well as refining exercise prescriptions tailored to AF patients.

ConclusionExercise has a significant effect on improving the exercise capacity, cardiorespiratory function, and quality of life in AF patients. Particularly, for cardiorespiratory function, the combined effect size after exercise shows a significant improvement, especially in patients under the age of 60. Additionally, exercise significantly reduces the resting heart rate of AF patients and improves symptoms of rapid heartbeats. This study emphasizes that the positive impact on AF patients is more pronounced when exercise intensity exceeds 50%, providing a new perspective for optimizing exercise prescriptions. The study provides high-level evidence on the role of exercise in AF treatment, highlighting the importance of personalized exercise plans in improving the cardiorespiratory health of AF patients. Future research should use larger sample sizes and higher-quality randomized controlled trials to further validate and refine our findings.

Ethical considerationsThis study does not involve ethical considerations as it is a systematic review and meta-analysis, and therefore does not require written informed consent.

Funding informationThis study received no funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.