Which strategic capabilities simultaneously drive innovation and learning from failures (LFF)? We address this question with two objectives. First, synergies between innovation performance, failures, and LFF strategies are assessed. Second, heterogeneities in the determinants of these processes are explored to identify common and specific predictors for each process. Based on a sample of 436 Canadian SMEs and drawing on the dynamic capabilities theory, we developed an original framework that disentangles the sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities. The econometric exercise revealed that complementarities between innovation failures and LFF and among LFF strategies emerge through complex interactions. Results show nuances regarding levels of microfoundation capabilities, such as those for seizing when managing innovation and LFF. This study provides practical insights for managers on improving innovation performance and capitalizing on unconventional solutions, such as previous failures. We discuss findings along with their theoretical and practical implications.

Innovation is no longer a “nice to have.” Indeed, like large companies, SMEs must innovate to survive in turbulent environments, acquire a competitive advantage, and ultimately thrive (Kraśnicka et al., 2018; Scuotto et al., 2023; Shaik et al., 2023). However, they struggle, as their large counterparts, with numerous internal and external barriers and management challenges that enhance the likelihood of failure of their innovation projects, generating wasted investments, sales below expectations, and costs that surpass projections (García-Quevedo et al., 2018; Coccia, 2023; Shaik et al., 2023; Almeida, 2024). In this vein, many previous studies have shown that the percentage of innovation projects and business initiatives that failed, either entirely or partly, is remarkably high and could exceed, in some sectors of activities, 70% of the initiated innovation projects (Rizova, 2006; Heidenreich & Kraemer, 2016; Perin et al., 2016).

Therefore, managers are challenged to learn from their previous failures and drawbacks, as Learning from Failures (LFF) is critical to organizational development and progress (Baxter et al., 2023; Chatterjee et al., 2023). The literature on this topic is vibrant and growing. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and leveraging failures as valuable learning experiences (Cannon & Edmondson, 2005; Love et al., 2023; Shaik et al., 2023). Porter-O’Grady and Malloch (2016) even consider that failure is the “lifeblood” of innovation. Failure is intertwined with innovation, which can be an inherent outcome of innovation projects (Jenson et al., 2016; Maslach, 2016; Rhaiem & Amara, 2021). Moreover, as argued by many authors (Carroll & Mui, 2008; Shepherd et al., 2009; Vittori et al., 2024), failure is not an entirely negative outcome, and a significant proportion of failures are underexploited sources of technological progress and social welfare improvement (Rhaiem and Amara, 2021). This observation "has led to a large body of prescriptive advice to embrace failure as a necessary ingredient of the innovation process" (Khanna et al., 2016, p. 436).

Firms can learn from their failures (internal or direct learning) or vicariously from others’ failures (vicarious or indirect learning). The former refers to a process in which a firm “reflects upon the problems and errors it experiences, interprets and makes sense of why they occurred, and discusses what actions are needed to produce improved outcomes” (Carmeli et al., 2012). The latter refers to how other firms’ failures may serve as wake-up calls, inciting not-yet-failing firms to develop new insights and search for new actions and routines that enable them to avoid the same mistakes (Kim and Miner, 2007). Vicarious learning is a different process, albeit complementary to internal learning, focusing on learning from other firms’ experiences (Carmeli and Dothan, 2017). However, much remains to be known about how firms learn from failure events and the factors that influence internal and vicarious learning from failures (Carmeli and Dothan, 2017; Tao et al., 2025).

From the above, we can argue that innovation, innovation failure, and learning from failures are intertwined processes, both from a technical and strategic perspective. Thus, it is of great interest in the innovation learning literature to examine the complementarity effects between these four processes empirically. It would also be interesting to disentangle each process's common and specific determinants. Specifically, the aims of this study were twofold: First, the complementarities among innovation performance, innovation failures, and internal and vicarious LFF were studied to assess the extent to which they are linked. Second, heterogeneities in the determinants of these processes were explored using a microfoundational framework based on dynamic capabilities (DC) to identify each process's common and specific predictors. Studying these synergies in combination with their determinants provides valuable insights that enable an in-depth understanding of SMEs' innovative capabilities and, ultimately, influence their behavior regarding the management of innovation within their walls.

This study contributes to existing literature on strategic management and innovation in several ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine simultaneously innovation performance, failures, and the two modes of LFF (internal and vicarious). Some previous studies have dealt with the simultaneous relationships between different types of innovation (e.g., Amara et al., 2009), innovation performance and innovation failures (e.g., D’Este et al., 2016), and amongst modes of LFF (Carmeli and Dothan, 2017). However, none have examined innovation performance, innovation failures and LFF jointly. Therefore, this study clarifies what has been done and the research gaps regarding the interplay between innovation, failure, and LFF. Second, to learn effectively from failures and innovate, SMEs need to leverage their internal capabilities and networking assets (Shaik et al., 2023; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Earlier studies have enriched our understanding of LFF by frequently using the Resource-Based View (RBV) and DC frameworks (Barney, 1991; Teece et al., 1997). Although these frameworks are relevant to discussing a firm’s resources, their scope remains limited to explaining the endogenous relationship between LFF and innovation performance. As pointed out by Chatterjee et al. (2023), quoting other authors (Abell et al., 2008; Felin et al., 2012, Helfat and Peteraf, 2015; Palmié et al., 2023), “research on strategic capabilities has tended to take a more macro-level approach (Ethiraj et al., 2005) and has overlooked the need to identify micro-foundations (Winter, 2003; Chatterjee et al., 2023). Therefore, our study expands our knowledge by introducing a novel framework based on the microfoundations of DC, which elucidates the lower level of a firm’s capabilities, including interactions among organizational members. Third, empirical evidence regarding the relationship between innovation failures and LFF across SMEs is lacking. Our emphasis on SMEs is justified because the corpus of prior studies addressing SMEs’ capabilities to learn from their previous innovation failures is limited. As stressed by Lafuente et al. (2025:1): “how entrepreneurs and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) learn has been sidelined in the literature”. Thereby, an interesting research gap regarding the lack of research must be addressed (Pierre and Fernandez, 2018; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023; Lafuente et al., 2025). Moreover, the learning process seems less efficient for SMEs than for large firms because of their limited capacity to detect and absorb knowledge and, thereafter, create a knowledge-based competitive advantage (Farace and Mazzotta, 2015; Liu and Laperche, 2015). Finally, from a Canadian perspective, SMEs account for many companies in Canada (98.1 % of all businesses with employees in 2021). They employed 13.7 million people in 2022, 85% of private and public sector employees (excluding the unemployed and self-employed) (Statistics Canada, 2022). Therefore, they are important targets for exploring these research topics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on the synergies among the four phenomena: innovation performance, innovation failures, and LFF mechanisms, and introduces the DC framework. Section 3 addresses methodological issues, including data collection procedures and econometric model specifications. Section 4 presents the results of statistical exercises. Section 5 discusses the main results and highlights the managerial and policy implications. Finally, Section 6 concludes and emphasizes the study’s limitations and possible directions for further research.

Theoretical backgroundDynamic capabilitiesThis study draws on DC theory to explore the synergies between innovation performance, failures, and LFF strategies. DC is rooted in a firm’s Resource-Based View (RBV). The RBV is characterized by a static view of a firm’s competitive advantage. DC extends to dynamic markets (Teece et al., 1997). Its framework encompasses an organization’s ability to manage its capabilities and resources to create new value in changing environments (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2020; Traoré et al., 2021). In that sense, DC theory sheds light on how organizations generate valuable and inimitable capabilities by reconfiguring competencies and resources when existing assets, resources, and knowledge become outdated due to environmental dynamism (Chirumalla, 2021; Rhaiem and Doloreux, 2022). The microfoundations perspective of DC advocates that a firm’s routines should be analyzed in terms of their underlying characteristics, systems, procedures, and lower-level interactions involving organizational members (Rhaiem and Doloreux, 2024). This conception of DC enables understanding a firm’s heterogeneity regarding its innovation and LFF capabilities (Magistretti et al., 2021). Teece (2007) regroups DC into three dimensions: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring.

- •

Sensing capabilities encompass a range of scanning activities that enable firms to understand their environments and identify potential threats and opportunities.

- •

Seizing capabilities encompass organizational structures, procedures, and incentives that facilitate the capture of business opportunities. These are essential when an original opportunity is identified. This represents a firm’s capacity to mobilize more assets in response to this opportunity.

- •

Reconfiguring capabilities typically encompasses the strategic renewal of firms through the combination and reconfiguration of their internal routines and processes to match the seizing process. In that sense, reconfiguring allows firms to create a better “alignment or fit” with their external environment.

This study examines the relationship between organizational failures and firms’ ability to innovate and manage a portfolio of LFF strategies as dynamic capabilities. First, the recent literature recognizes the importance of approaching innovation activities as dynamic processes from a micro-foundational perspective (Fallon-Byrne and Harney, 2017; Sheehan et al., 2023; Rhaiem and Doloreux, 2024). Innovation implies disruptive changes in the way things are done, requiring firms to rethink their resources and competencies to align with new realities. Therefore, dynamic and uncertain decisions that disturb organizational routines and behaviors are conducive to innovation (Fallon-Byrne and Harney, 2017). Second, like innovation, both learning activities (internal and vicarious) are perceived as dynamic processes that deal with market changes. Indeed, scholars have a consensus that DC is built and developed through learning processes (Zollo and Winter, 2002; Mohaghegh & Größler, 2022). LFF is the operational process of obtaining information about failures and converting it into valuable knowledge (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Giniuniene and Jurksiene, 2015). Vicarious learning is a social process based on interactions between partners and observing others’ behaviors to learn from mistakes and pitfalls. Therefore, both LFF strategies are embedded in DC because they support organizational agility, through which firms acquire continuous knowledge and modify their routines for improved performance (Bingham et al., 2019). Third, abandoning an innovation project is a dynamic outcome that may be perceived as negative if firms fail to learn from their failures (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). However, abandonment may create a competitive advantage by providing unique knowledge for future innovation activities. In this vein, scholars discuss concepts such as “intelligent failure,” “fast failure,” and “failing well” as the dynamic outcomes of competitiveness and growth (Edmondson, 2011; Koporcic et al., 2025).

In summary, each concept discussed above embodies a dynamic process or outcome, and mastering the synergies between these concepts requires firms to leverage their DC to pursue competitiveness.

Relationship between innovation performance and failuresAs contended by Coccia (2023), innovation failures occur “when an organizational system misses the goal of a designed project of innovation at time t or in a specific period.” Two streams of literature continue to debate the nature of the relationship between innovation performance and innovation failure. The first stream of studies found a positive association between failure and innovation. Many scholars belonging to this stream argue that failures are valuable inputs for future innovation projects (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005; Edmondson, 2018; Vittori et al., 2024). These failures provide firms with a signal to renew their current policies and organizational strategies, thereby increasing the likelihood of success in future innovation projects (Rhaiem, 2018; Kim and Lee, 2020). Similarly, Vittori et al. (2024) argue that failures are followed by deliberate experimentation. This is a provocative process that increases the likelihood of innovation failure. Consequently, we often fail but have more opportunities to find new solutions that enhance our future disruptive innovation outcomes (Vittori et al., 2024). Likewise, another stream of research supports a negative relationship between innovation and failure. According to Chatterjee et al. (2023) and Rhaiem and Halilem (2023), innovation failure is a negative outcome that occurs when firms fail to learn from their experiences. In this case, firms fail twice: they innovate and learn from failure. Psychologically, employees and managers are emotionally engaged in innovative projects. Failure will cause innovation trauma, defined as “the inability to commit to a new innovation due to severe disappointment from previous innovation failures” (Välikangas et al., 2009: 226). Hence, failures do not necessarily lead to organizational renewal, and firms can attribute these failures to uncontrollable events or factors they cannot analyze internally (Kc et al., 2013; Kim and Lee, 2020).

Hence, considering the findings of these two opposing streams of studies, we contend that the relationship between innovation performance and innovation failures is an empirical matter. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

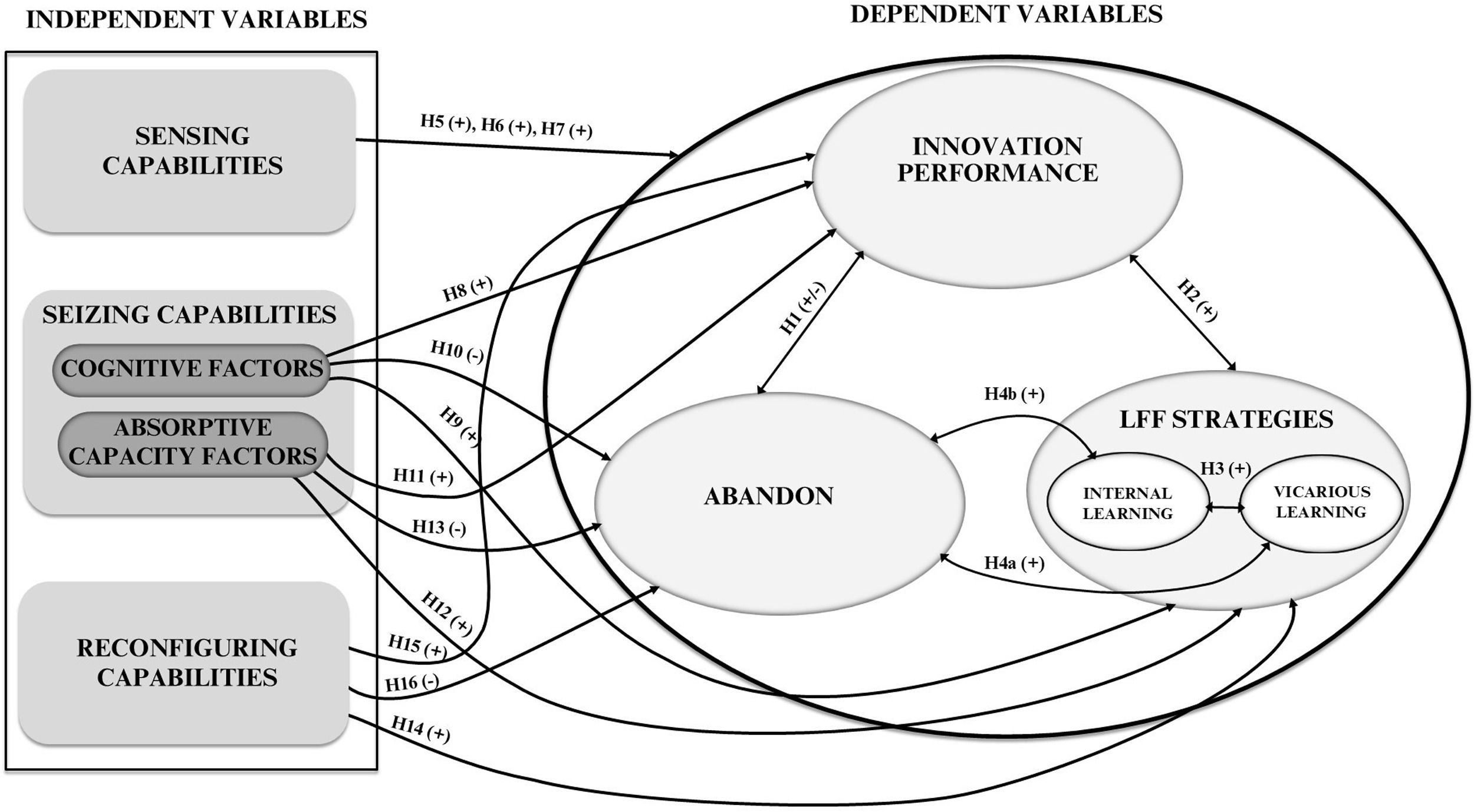

H1 Innovation performance and innovation failures may be positively or negatively associated.

Previous studies have provided numerous insights suggesting that innovation performance and learning from previous failures (LFF) are closely linked (Sosna et al., 2010; Carmeli et al., 2012; Shaik et al., 2023). LFF is an organizational practice that analyzes previous failures to enhance a firm’s future performance. Therefore, innovation performance and LFF are interdependent, and LFF may be insightful at all stages of the innovation process, assuming that failures are recognized as valuable resources (Bruneel et al., 2010; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023; Baxter et al., 2023).

The positive relationship between LFF and innovation performance is supported by the assumptions of the absorptive capacity (AC) theory. Cohen and Levinthal (1990:128) define AC as “the ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends.” Firms endowed with high AC strengthen their capacity to deal with internal or external flows of knowledge related to their own failures. In summary, learning from failed organizational initiatives is closely linked to a firm’s readiness for upcoming innovations, provided that it is accompanied by a willingness to learn and a safe organizational culture (Shaik et al., 2023; Tao et al., 2025).

Theoretically, the positive relationship between LFF and innovation performance appears obvious, but empirical contributions to this topic remain scarce. Based on the above discussion, we hypothesize the following:

H2 Innovation performance and LFF are positively linked.

Learning is a vital process that enhances an establishment’s innovation and performance (Hsu and Fang, 2009; Carmeli and Dothan, 2017). Drawing on organizational learning literature, we highlight two forms of LFF: internal and vicarious learning. First, internal LFF is based on direct learning from previous experiences within a firm (Carmeli, 2007). Argyris and Schön (1978) distinguished between two learning mechanisms: single-loop and double-loop learning. The key distinction is that single-loop learning implies a solution to an immediate mistake without analyzing or investigating its root cause, whereas double-loop learning incorporates an analysis process to prevent the same mistake from occurring in the future (García-Morales et al., 2009; Carmeli and Dothan, 2017).

Given the dynamism of markets, single-loop learning has become outdated, and scholars have increasingly focused on double-loop learning (Carmeli, 2007; Carmeli & Dothan, 2017; Rhaiem & Halilem, 2023). Second, vicarious learning is a social process based on indirect learning (Bandura, 1977). Through interaction, observation, and imitation, firms accumulate knowledge from other organizations (Magazzini et al., 2012; Carmeli and Dothan, 2017), attempt to imitate their successful practices, and avoid mistakes (Denrell, 2003).

Prior studies have primarily focused on internal learning (Tucker & Edmondson, 2003; Carmeli, 2007; Shaik et al., 2023). A few studies have focused on vicarious learning (Bledow et al., 2017; Kim and Miner, 2007). In addition, these recent studies have rarely examined internal learning and vicarious learning simultaneously (Carmeli and Dothan, 2017;Tao et al., 2025 ). Indeed, research in this stream has obscured the issue of a potential learning process that may begin with social learning and conclude through internal learning, or vice versa. Authors such as Carmeli and Dothan (2017) or Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer (2014) argue that the LFF may not be a straightforward phenomenon, as some studies have suggested. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to the ongoing debate by drawing on the DC framework and social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) to clarify the relationship between the two modes of LFF. It is worth mentioning that both LFF strategies depend on a firm’s observation capacity, which may help screen and best understand business environments. Engaging in either internal or external learning activities helps organizations develop unique observation skills that enhance their sensing capabilities for identifying potential future failures. Hence, engaging in one LFF mode is potentially beneficial for the other mode. Based on this rationale, we hypothesize the following:

H3 Internal and vicarious LFF are positively associated.

The literature has a broad consensus that learning strategies and failures are positively related (Carmeli, 2007; Yamakawa and Cardon, 2015; Vittori et al., 2024). Companies can learn from their own experiences or from the failures of other companies to improve their practices and routines (Baxter et al., 2023; Love et al., 2023). Hence, failures derive valuable knowledge for learning and may constitute an intermediate step before success (Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Thus, failures and LFF are closely related and tend to be positively associated (Love et al., 2023). However, some studies suggest that failures can serve as a substitute for LFF in certain situations. Edmondson (2019) argues that failures are not always accompanied by learning behaviors in firms. Likewise, Shepherd and Kuratko (2009) demonstrate that “project death” generates grief in firms, an emotional reaction that hinders learning processes. Based on the above and following mainstream contributions, we hypothesize:

H4a Internal LFF and failures are positively associated.

H4b Vicarious LFF and failures are positively associated.

The determinants of the four dependent variables considered in this study were regrouped according to Teece’s (2007) suggestion of three dimensions of dynamic capability: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring.

Sensing capabilities: knowledge sourcing activities and social capitalDrawing on the DC framework, the sensing capabilities refer to a firm’s ability to continuously scan organizational environments and filter information and opportunities (Teece, 2007). In this sense, firms perceive environmental signals that other firms can miss, which enhances their understanding of external threats and opportunities (Harvey, 2025).

Literature on innovation, rooted in the microfoundations of DC, offers several approaches to capturing a company’s sensing capabilities (Chirumalla, 2021; Rhaiem and Doloreux, 2024). Surprisingly, the literature on the relationship between LFF and innovation overlooks the important role of firms’ informational capabilities (Harvey, 2025; Kim and Lee, 2020). We fill this gap by approaching sensing capabilities through the lens of knowledge acquisition, which is fundamental to learning from failures (Zollo and Winter, 2002; Harvey, 2025). Specifically, this study considers three sensing capabilities: internal knowledge search, external knowledge search, and social capital.

First, knowledge search practices involve acquiring new knowledge that expands a firm’s knowledge base and stimulates new ideas (Nonaka et al., 1996). Many scholars perceive knowledge-sourcing activities (internal or external) as learning processes that enhance a firm’s ability to anticipate market dynamism and ensure a competitive response based on new knowledge acquired (Ahmed et al., 2017; Lee and Yoo, 2019; Hutton et al., 2024). Therefore, firms engage in knowledge search activities as part of their sensing activities to navigate their uncertain environment (Lee and Yoo, 2019; Alshanty and Emeagwali, 2019; Kim and Lee, 2020) and to increase their chances of gaining insights from past failures (Desai, 2020). Moreover, firms that are more involved in knowledge search have more options to deal with failures than those that are not (Laursen & Salter, 2006; Kim and Lee, 2020).

Second, numerous studies have demonstrated that social capital enhances firms’ innovation performance (Landy et al., 2002; Maurer et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2021). Moreover, the interpersonal relationships between participants, the sharing of information, and the co-creation of meanings between partners allow firms to learn and assimilate new knowledge (Hughes et al., 2014). Bogenrieder (2002) confirms that social capital, developed through socialization processes, is a prerequisite for organizational learning. However, the literature has only taken the first faltering steps to explore the association between social capital and LFF behaviors (Carmeli, 2007; Gu et al., 2013; Rhaiem and Amara, 2021). Indeed, at the empirical level, there remains a scarcity of studies that have established a positive association between social capital and LFF strategies (Carmeli, 2007; Hughes et al., 2014).

Third, firms seek external knowledge from diverse actors to complement internal expertise and enhance innovation. They interact with other firms and various types of actors, increasingly relying on external sources to access valuable knowledge (Tether, 2002; Amara et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2022). This external search helps identify and acquire new ideas that validate in-house knowledge, increasing the likelihood of successful innovation (Bougrain & Haudeville, 2002; Li & Gao, 2023; Lopes-Bento and Simeth, 2024) ). Actors providing such knowledge are diverse, often categorized as either market sources (such as competitors, suppliers, and clients) or research and institutional sources (including laboratories, universities, and research centers) (Shearmur & Doloreux, 2013; Vega-Jurado et al., 2008). Market sources, including industry peers and value chain partners, keep firms informed about market needs and enhance adaptation during later innovation stages, thereby decreasing the risk of project failure (D’Este et al., 2016). In contrast, research and institutional sources can support riskier and more radical innovations, helping firms manage complex problems, particularly in early development stages, and reducing failure risk (D’Amico et al., 2025).

Likewise, social capital is often heralded as a driver of innovation. It enables trust and facilitates the exchange of knowledge and resources within networks (Filieri & Alguezaui, 2014). However, strong and dense relationships may also restrict innovation by promoting conformity and discouraging the adoption of radical ideas (Ceci et al., 2020). Large ego-networks can generate a higher volume of ideas, but the presence of many structural holes may lower the quality of these ideas due to difficulties in leveraging these connections (Björk et al., 2011). Furthermore, while social capital and embeddedness typically support innovation, firms may still experience failure if their networks lack diversity or depend excessively on similar, trusted partners (Molina-Morales & Martínez‐Fernández, 2010).

In summary, innovation and LFF depend on a firm’s relational activities through knowledge search processes. The latter constitutes a sensing capability embedded in Social Learning Theory (SLT) (Bandura, 1977)), and the LFF occurs through a relational process of human interactions (Gu et al., 2013; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Therefore, sensing capabilities (internal knowledge search, external knowledge search, and social capital) facilitate LFF activity and enhance innovation performance.

In this study, sensing capabilities, which refer to internal knowledge search, external knowledge search, and social capital, are captured by internal and external sources of information used by the firm to inform its innovation activities, as well as an index reflecting the interactions of employees within and outside the firm. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H5 Sensing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on innovation performance.

H6 Sensing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on LFF strategies.

H7 Sensing capabilities have a significant and negative impact on innovation failures.

Teece (2014) defines seizing capabilities as a firm’s ability to mobilize resources in response to a new opportunity. They refer to the competence to seize an opportunity by making the right decision (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008). Seizing involves deploying resources and engaging in activities that support the development of innovative outputs, including products, processes, and services, that arise from sensed opportunities (Chirumalla, 2021; Hutton et al., 2021). Two main determinants are at the heart of firms’ seizing capabilities: cognitive factors and absorptive capacity.

Drawing on the cognitive psychology literature (Nooteboom, 2009), we note that the role of cognitive determinants in contributing to the seizing of opportunities in LFF remains unclear. Indeed, scholars call for a better understanding of the relationship between cognitive determinants, notably psychological safety, trust, and LFF (Edmondson, 2018; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023).

Psychological safety is “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking” (Edmondson, 1999, p. 354). Safe employees feel free to reveal failures and ask for help (Eldor et al., 2023). Therefore, psychological safety alleviates fear, which may inhibit innovation and learning activities by hiding errors, interrupting critical thinking, and avoiding risky initiatives (Kuyatt, 2011).

There is a broad consensus that psychological safety improves LFF and innovation performance (Carmeli, 2007; Gu et al., 2013; Edmondson, 2018). LFF is a social-interactional process involving collective thinking, risk-taking, and open discussions, which requires a safe climate within a firm’s walls to succeed (Hirak et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2013; Newman et al., 2017). However, recent studies challenge the mainstream literature by advocating that psychological safety may lead to excessive employee confidence, resulting in negative outcomes (Edmondson, 2018; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023; Eldor et al., 2023). Drawing on the cognitive distraction theory ( Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), these studies argue that there is a bounded capacity for cognitive resources and that an excess of psychological safety can decrease employee performance (Eldor et al., 2023).

Similarly, trust is widely recognized as a cognitive enabler of oriented learning behaviors and innovation. Trust is a psychological state in which employees make themselves vulnerable to relationships based on their beliefs and expectations that a second party will react positively (Mayer et al., 1995; Robinson, 1996; Rousseau et al., 1998). Hence, when employees trust each other, they are encouraged to share and discuss their failures openly (Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Therefore, trust is important in promoting LFF and innovation ecosystems (Carmeli et al., 2012; Steinbruch et al., 2022). Psychological safety and trust were the two variables considered to predict cognitive-seizing capabilities. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H8 Cognitive seizing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on innovation performance.

H9 Cognitive seizing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on learning from failure strategies.

H10 Cognitive seizing capabilities have a significant and negative impact on innovation failure.

Similarly, absorptive capacity (AC), which refers to “the ability of a firm to recognize the value of new external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends” (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) is considered a vital ingredient that supports firm performance (Flatten et al., 2011; Kale et al., 2019), innovation success (Zhao et al., 2021) and organizational learning (Sun & Anderson, 2010; Traoré et al., 2021).

The body of knowledge on the positive relationship between AC and innovation is well-developed (Flor et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2021). AC facilitates external knowledge acquisition and assimilation, which helps firms better understand their markets and is crucial for generating innovative outputs in response to dynamic environments (Tsai, 2001; Kostopoulos et al., 2011). Moreover, since the seminal work by Cohen and Levinthal (1990), scholars have consistently found that AC is positively associated with organizational learning (Naqshbandi and Tabche, 2018; Darwish et al., 2020). A learning-oriented culture depends on knowledge creation, diffusion, and internalization. AC reinforces this culture by enabling firms to absorb knowledge from new sources (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Naqshbandi and Tabche, 2018). However, in the specific literature on LFF, contributions regarding the role of AC remain scarce. To our knowledge, with a few exceptions (Gebauer et al., 2012; De Araújo Burcharth et al., 2015), the role of AC in explaining learning strategies from failure remains understudied.

In summary, psychological factors (psychological safety and trust) are conceptualized as cognitive seizing capabilities. A firm’s willingness to invest resources in structures and routines that promote a safe workplace leads to higher performance in terms of learning and innovation. A firm’s AC (captured by internal R&D and knowledge employees) is widely recognized as a dynamic capability that facilitates its absorption of new knowledge, which helps seize identified opportunities and sometimes compensates for weak in-house capability. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H11 AC Seizing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on innovation performance.

H12 AC Seizing capabilities have a significant and positive impact on learning from failure strategies.

H13 AC Seizing capabilities have a significant and negative impact on innovation failure.

Reconfiguring capabilities are embedded in the organizational routines, processes, and cultures required to orchestrate and renew a firm’s tangible resources and competencies (Teece, 2007; Khan et al., 2021). Therefore, organizations strive for greater flexibility by pursuing structural decentralization, fostering employee autonomy, and cultivating a culture of knowledge sharing (Chirumalla, 2021).

This study captures a firm’s reconfiguring capabilities through two determinants: learning leadership (Denti and Hemlin, 2012) and intellectual property protection (IPP) (Chesbrough, 2003; Candelin-Palmqvist et al., 2012). First, learning leadership can be considered a form of organizational support leaders provide to achieve innovation and learning goals (Stoker et al., 2001; Carmeli & Sheaffer, 2008). Organizational failure often instills fear among employees, who seek a supportive leader to alleviate this fear (Carmeli & Sheaffer, 2008; Bligh et al., 2018). Leaders should embody a failure-tolerant leadership style by encouraging employees to accept failures and take calculated risks (Farson and Keyes, 2006). They should encourage the establishment of a climate of openness that encourages the free exchange of solutions to resolve mistakes and ultimately learn from them (Edmondson, 2004; Carmeli & Sheaffer, 2008; Hirak et al., 2012; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Thus, as Carmeli & Sheaffer (2008) showed, learning leadership and LFF are positively related. Second, formal and informal IPP methods are levers for firm innovation (Kalanje, 2006; Halilem et al., 2017). Indeed, firms actively seek to preserve their competitive advantage by preventing imitation through protection strategies (Chesbrough, 2003; Candelin-Palmqvist et al., 2012). Many scholars have highlighted the positive relationship between IPP and innovation (Amara et al., 2008; Sukarmijan and Sapong, 2014).

Regarding learning from failures to our knowledge, no previous studies have focused on its relationship with intellectual property protection. However, protected inventions involve complex activities that entail deep thinking and technical processes. Throughout the development stages, firms develop their ability to invent, protect knowledge, and effectively manage resources (Rhaiem and Doloreux, 2024). We categorize this tacit knowledge as a reconfiguring capability that enables a firm to renew itself, learn from failures, and innovate.

In this study, reconfiguring capabilities were captured using two variables: organizational support and intellectual property protection. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H14 Reconfiguring capabilities (organizational support and intellectual property) has a significant and positive impact on learning from failure strategies.

H15 Reconfiguring capabilities (organizational support and intellectual property) has a significant and positive impact on innovation performance.

H16 Reconfiguring capabilities (organizational support and intellectual property) has a significant and negative impact on innovation failure.

To visually synthesize the relationships outlined in the previous sections, the links between the four dependent variables and explanatory variables considered in this study are depicted in Fig. 1.

Method and empiricsData collection procedureComputer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) were conducted by a private firm. The data were collected between September 2017 and February 2018 in the Montérégie region in Québec, Canada. The questionnaire was inspired by the third edition of the Oslo Manual (2005) and several previous studies on innovation (Robinson, 1996; Edmondson, 1999; Carmeli, 2007; García-Morales et al., 2009). The main purpose of the survey was to ask about innovation and its determinants in manufacturing companies, as well as LFF and its determinants.

The initial population included 2,286 firms, of which 712 were not interviewed for various reasons (unreachable numbers, declared bankruptcy, and lack of fit with the study criteria). Moreover, when the survey was administered, 960 organizations refused to participate. Thus, we obtained 598 completed surveys for a response rate of 37.99% (598/1574 organizations). This rate compares favorably with those of other studies. For example, studies on the innovation practices of small- and medium-sized manufacturing firms achieved response rates of 32.5% in Australia (Terziovski, 2010), 11.68% in Spain (Van Auken et al., 2008), and 17.2% in the UK (Tomlinson, 2010). We retained only innovative firms (based on the Oslo Manual definition of introducing innovation in the three years before data collection). The final set of 436 usable questionnaires generated data from a sufficiently large number of firms to capture complete information and heterogeneity among organizations.

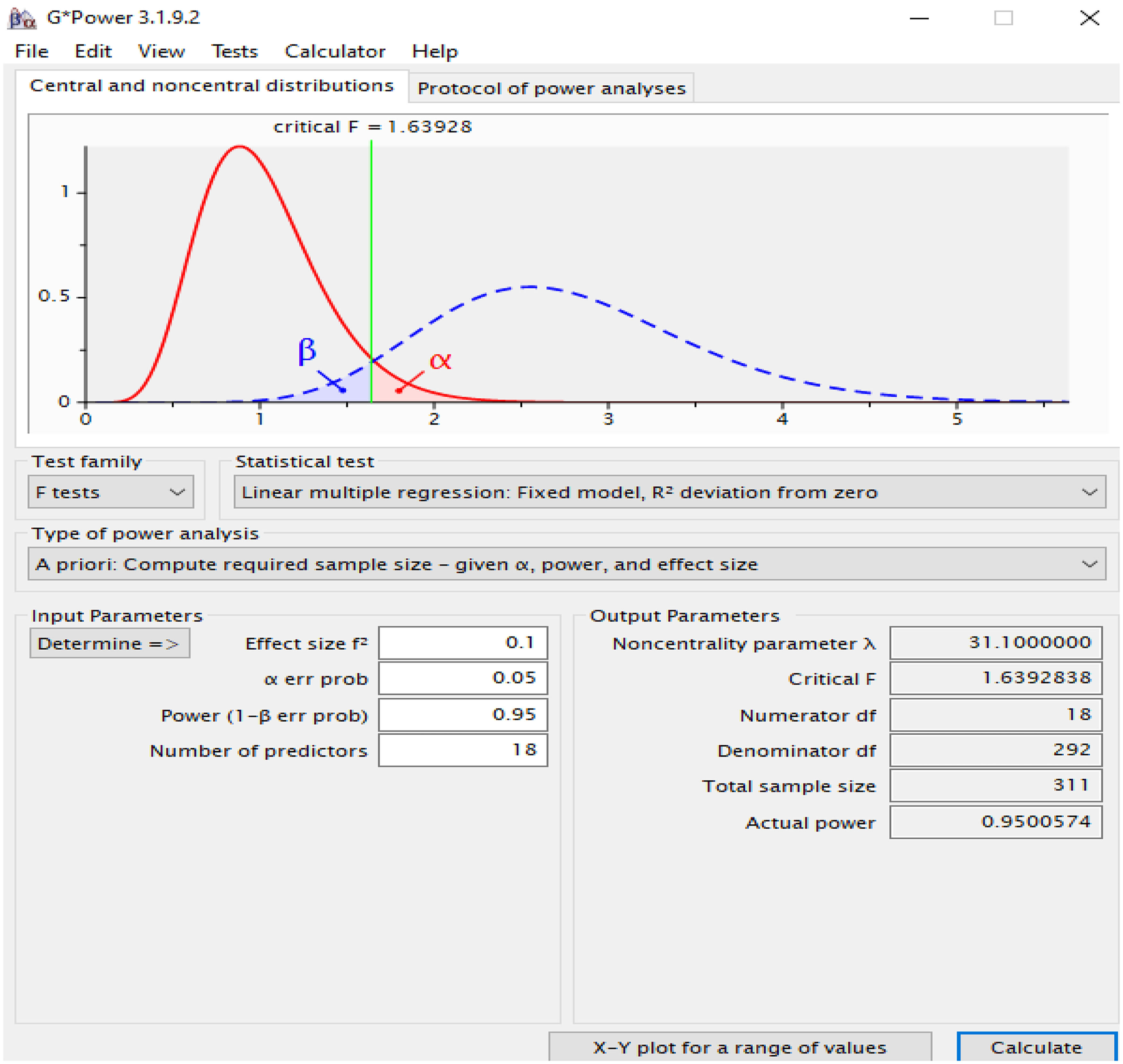

To assess the representativeness of our sample, a post-hoc power analysis with the statistical program G*power 3.1.9 (Faul et al., 2013) was conducted to assess the appropriate sample size for the statistical analysis to be performed, and the possibility of committing a Type I or II error (Bartlett et al., 2001; Faul et al., 2009; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). More specifically, with an alpha of 0.05, a power level of 0.95, and a small effect size of 0.10, the minimal sample size for the regressions with 18 explanatory variables we should achieve is 331. Given this result, our sample was sufficiently large to meet these data considerations, i.e., the number of valid cases included in our model (n = 436) is higher than what is required to detect a ‘true’ effect when it exists (See Appendix 1).

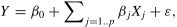

Econometric models specificationThe analytical plan comprised three stages. First, we simultaneously estimated four regressions (i.e., using Mplus 8.6) to explore the correlates of the four dependent variables considered in the study: innovation performance (PERFOR), abandonment (ABAND), internal learning (LEARN), and vicarious learning (VICAR). Such a mixed response path model accommodates a joint estimation of several types of regressions while controlling mutual correlations between disturbances (Landry et al., 2013; D’Este et al., 2016). In this study, ordinary least squares regression was used for the three outcomes measured on normal continuous scales (PERFOR, ABAND, and LEARN), while ordered logit regression was used for the outcome VICAR, as it was measured on a 5-point ordinal scale (1 = Disagree completely, and 5 = Completely agree). We used the weighted least squares mean, and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator as it outperformed the standard ADF-WLS estimator for small and medium samples (Flora and Curran, 2004; Ouimet et al., 2007)1

Specifically, for each of the three dependent variables PERFOR, ABAND, and LEARN, we developed the following ordinary least squares model:

where Y is the dependent variable, β0 is the model’s intercept, X j corresponds to the model’s jth explanatory variable (j=1 to p), and ε is the random error with expectation 0 and variance σ².For the dependent variable VICAR, which is measured on an ordinal scale, we developed the following ordered logistic equation:

where Xi is the vector of K explanatory variables for scholar i and β is the vector of parameters to be estimated to assess the effect of the K explanatory variables on VICAR*. εi is the error term for scholar i assumed to be normally distributed, with the mean and variance normalized to 0 and 1, respectively. VICAR*i is a latent continuous variable underlying the ordered observed variable Yi where,- •

Yi = 1 (Disagree completely) if Y* < α1

- •

Yi = 2 (Disagree somewhat) if α1 ≤ Y* <α2

- •

Yi = 3 (Neutral) if α2 ≤ Y* <α3

- •

Yi = 4 (Agree somewhat) if α3 ≤ Y* < α4

- •

Yi = 5 (Completely agree) if Y* ≥ α4

Secondly, the same model was estimated by fixing insignificant regression coefficients (i.e., those with a p-value greater than 0.10, two-tailed) to 0. As Golob and Regan (2002, p. 217) argue, fixing insignificant parameters enables the estimation of a model with fewer degrees of freedom. Saturated models, such as those estimated in the first stage, always fit perfectly, as they typically have 0 degrees of freedom. In other words, the models' fit could not be assessed. Therefore, in this study, we only present the fit of the unsaturated model, which discards the insignificant parameters removed in the saturated model estimated in Step 1.

Third, we estimated the same unsaturated path model, but with the covariances between the error terms of the equations fixed at 0, to assess the appropriateness of using a multi-response path model instead of separate regression models. A comparison of this constrained unsaturated path model with an unsaturated path model that includes free error terms allows for the assessment of whether simultaneous estimation of the four regressions is more appropriate than using separate regression models. If so, then the free error-term covariances serve as proxies for the complementarity, substitution, or independence effects between the four outcomes considered in our study.

In this study, the correlation approach was preferred to conduct the analysis. This approach tested the correlations between the dependent variables conditional on a set of independent variables. It asserts that complementarity arises when the null hypothesis of no correlation between the residuals of two or more regression equations is rejected (Landry et al., 2013; D’Este et al., 2016). The correlation approach is superior to other techniques in literature (the reduced form exclusion restriction approach, the productivity approach) for many reasons: 1) it does not require the specification of an objective function. It uses choice variables as dependent variables in regression models and tests directly for the presence or absence of complementarity effects between them (Galia and Legros, 2004); 2) does not limit the number of choice variables under scrutiny to test for complementarity effects. Hence, as we consider four choice variables in this study, approaches that cannot accommodate more than two choice variables are inappropriate.

Appendix 2 provides an overview of the detailed operationalization of the dependent variables, as well as factors that may affect them. Descriptive statistics confirm that the multiple-item scales are reliable and that there is no concern of multicollinearity (Field, 2024).

RESULTSSample characteristicsThe upper part of Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the four dependent variables considered in this study: innovation performance, abandoned innovation activities, internal learning, and vicarious learning. Of the 436 respondents, approximately one-third of the turnover generated during the three years preceding the survey was from products that were new or significantly improved (32.71%; SD = 24.20%). On average, 2.25 innovation activities were abandoned by firms in the sample over the last three years (SD = 4.63). Likewise, the mean of the weighted five-item index of internal learning was 3.93/5 (SD = 0.75). Finally, the distribution of companies regarding vicarious learning shows that 62.2% of them agree somewhat or completely that their organization always tries to learn from the successes and failures of other organizations.

Descriptive Statistics.

The lower part of Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of the explanatory variables considered in this study. The average firm had 37.30 employees (SD = 101.89). This accounted for 7.12% (SD = 17.82) of the R&D activities. On average, firms used 1.48 (SD = 1.07) out of 8 intellectual property protection methods to maintain or enhance their competitiveness in product or process innovation over the last 3 years. These were ranked at 4.33 (SD = 0.59), 2.85 (SD = 0.92), 3.37 (SD = 0.61), and 3.29 (SD = 0.71) out of a maximum of 5 on the weighted scales of psychological safety, organizational support, trust, and social capital, respectively.

Suppliers (81.7%), clients (76.1%), and professional and sectoral associations (49.1%) were the most frequently used sources of information for firms developing new products and processes. The least used sources were government institutions and research laboratories (20.2%), internal sources (31.4%), and universities (31.9%). Also, 35.8% of firms had internal R&D activities over the three years before the survey. 32.8% were part of a larger firm group. 52.3% operated in high- or medium-technology-intensive sectors.

Regression resultsIn this study, we report the results of the unsaturated path model, which includes only the significant coefficients found after estimating the saturated path model. However, the latter's fit could not be assessed. Golob and Regan (2002, p. 217) noted that “saturated models are difficult to interpret because statistically significant effects can be diminished due to multicollinearity with insignificant effects.” Thus, parameters with p > 0.10 (two-tailed) were set to 0. The unsaturated path model was then used to assess fit, as it had nonzero degrees of freedom (Golob and Regan, 2002; Amara et al., 2015).

Table 2 shows that the unsaturated path model fits well, as indicated by the chi-square statistic of 93.11 (p-value = 0.065) at the 5% significance level. This means the model adequately represents the relationships in the data. The R2 estimates, also in Table 2, reveal that the model explains a substantial proportion of the variance in innovation performance (R2 = 0.438) and internal learning (R2 = 0.391), making these the most clearly explained dependent variables.

Unsaturated Multivariate Path Model Results.

*, **, and *** indicate that the coefficient is significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1% thresholds, respectively.

aLN indicates a logarithmic transformation.

To assess whether it is appropriate to consider the four dependent variables simultaneously, we also estimated the same unsaturated path model with the covariances between the error terms set to 0. The Computed Likelihood Ratio Index (LR index) compares the Log Likelihood values from the unsaturated model and the model with zero covariances between error terms. The LR index is significant at the 1% level (χ² = 190.67, p < 0.001). This result strongly rejects the null hypothesis that all error-term covariances are zero, indicating that the four dependent variables share unexplained associations that are important to account for. Thus, separate regressions would ignore these correlations and are not appropriate for estimating the determinants of the four dependent variables in our study.

Complementariness, substitution, and independency between innovation performance, innovation abandon, and learning from failuresThe results regarding the error-term covariances between the four dependent variables are summarized at the bottom of Table 2. All these covariances are significant at a 5% level, except for the one between innovation abandon and vicarious learning. The last two outcomes thus appear independent. The insignificant covariance between their estimated disturbances supports this conclusion. The results show complementarities, with positive and significant covariances, between innovation performance (PERFOR) and internal learning (LEARN), innovation performance (PERFOR) and vicarious learning (VICAR), and between internal learning (LEARN) and vicarious learning (VICAR). The results provide evidence of substitution effects between innovation performance (PERFOR) and innovation abandonment (ABANDON), as well as between innovation abandonment (ABANDON) and both types of learning (LEARN and VICAR). The highest covariances are between innovation performance and internal learning (0.449), and between internal and vicarious learning (0.385).

Overall, these results support the idea that innovation performance and learning from failures are interdependent. Internal and external learning are also interconnected. Importantly, learning from innovation failures reduces innovation abandonment, while high innovation performance, especially with many and riskier projects, is linked to lower subsequent abandonment.

Effects of explanatory variables on the dependent variablesThe results in Table 2 show that from nine to thirteen independent variables are significant at levels from 1% to 10% in each of the four equations. For the sensing capabilities factors, the results show that three sources—suppliers, clients, and technical, industry, and service standards—are significantly and positively linked to innovation performance and both types of learning. At the same time, they are significantly and negatively linked to innovation abandonment. Two other sources—universities, scientific literature, and professional publications—are significantly and positively linked to internal learning. Information from professional and sectoral associations has a significant and positive impact on vicarious learning, while also negatively affecting the abandonment of innovation. Finally, internal sources are significantly and positively associated with innovation performance. Social capital has a significant and positive impact on both types of learning (internal and vicarious).

For the cognitive factors of seizing capabilities, the results show that psychological safety is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and internal learning. Trust is significantly and positively associated with internal learning and significantly and negatively associated with innovation abandonment. For absorptive capacity factors, internal R&D is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and negatively associated with innovation abandonment. The variable for knowledge employees is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and both types of learning. It is significantly and negatively associated with innovation abandonment. Likewise, for reconfiguring capabilities factors, the results show that organizational support is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and vicarious learning. At the same time, it is significantly and negatively associated with abandoning innovation. Intellectual property protection is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and vicarious learning. Finally, for the control variables, the results show that firm size is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and both types of learning. It is significantly and negatively associated with innovation abandonment. Being part of a group (subsidiary firm) is significantly and positively associated with innovation performance and internal learning, and negatively with innovation abandonment. Operating in a high- or medium-technology-intensive sector has a significant positive impact on innovation performance and a significant negative impact on innovation abandonment.

Findings discussionThe findings regarding complementariness mostly support our hypotheses. They support the hypothesis of interdependence between innovation performance and learning from failures. They also support the interdependence between internal and external learning. These results align with claims in favor of the complementarity effects between innovation performance and strategies of learning from previous innovation failures and drawbacks (Carmeli et al., 2012; Rhaiem and Amara, 2021; Shaik et al., 2023). The LFF appears to be an intermediate step that precedes SMEs’ innovation success. We also found a positive association between the two LFF modes (internal and vicarious). This finding supports our reasoning that using one LFF mode helps a firm manage the other.

The results also support the hypothesis that learning from innovation failures reduces the chance of innovation abandonment. This finding is consistent with organizational learning theory, which posits that learning is an ongoing process for improving firm practices and routines. However, the hypothesis of a substitution effect between innovation abandonment and vicarious LFF was not supported. This unexpected result may stem from the internal synergies between innovation performance and failure. Vicarious LFF enhances overall innovation performance, but it does not work the same way as failure. This could be due to the emotional component often present in failures. Firms must experience failure to gain the knowledge needed to anticipate future failures. More research is needed to understand vicarious LFF both theoretically and empirically.

Our results also reinforce studies showing that innovation projects engage employees and managers emotionally (D’Este et al., 2016; Kim and Lee, 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2023). Failure can cause innovation trauma, which hinders ongoing and future innovation activities (Välikangas et al., 2009; Chatterjee et al., 2023).

The results provide new insights into SMEs’ dynamic capabilities by exploring differences in microfoundation capabilities: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. First, we found that variables related to sensing capabilities explain the four dependent variables differently. Internal knowledge search leads to better innovation performance, while external knowledge search enhances LFF strategies and lowers failures. Social capital is also positively tied to LFF strategies. This suggests that strong relationships among employees encourage learning in SMEs. Second, for SMEs’ seizing capabilities, we found that cognitive determinants (such as psychological safety and trust) are significantly related to innovation performance, failures, and internal LFF, but not to vicarious learning. This makes sense because vicarious LFF is a social process. It involves observing and imitating others, limiting risk, and not requiring a positive mindset. The results also suggest there are boundaries between psychological safety and trust (Edmondson, 2018). Feeling psychologically safe at work encourages innovation, while trust reduces the likelihood of failure. Our findings partially support our hypotheses on AC. AC is a valuable seizing capability for SMEs. It is significantly related to the four phenomena, whether through internal R&D or knowledge employees. Similarly, trust is widely recognized as a cognitive enabler of oriented learning behaviors and innovation. Trust is a psychological state in which employees make themselves vulnerable to relationships based on their beliefs and expectations that a second party will react positively (Mayer et al., 1995; Robinson, 1996; Rousseau et al., 1998). Hence, when employees trust each other, they are encouraged to share and discuss their failures openly (Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Therefore, trust is important in promoting LFF and innovation ecosystems (Carmeli et al., 2012; Steinbruch et al., 2022). Psychological safety and trust were the two variables considered to predict cognitive-seizing capabilities. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Third, in capability reconfiguration, we found organizational support and intellectual property relate positively and significantly to vicarious, but not internal, LFF. This suggests that leadership or dormant knowledge helps social learning in SMEs. There is a contrast with Carmeli and Sheaffer (2008), because learning leadership is not linked to internal LFF. Further empirical studies are needed to clarify the impact of leadership on LFF strategies.

Theoretical implicationsThis research offers several theoretical implications. First, we develop a new framework based on the microfoundations perspective of DC. This framework advances knowledge by focusing on specific SME resources rather than general frameworks. Using the DC perspective, we explore SMEs’ sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities. This helps clarify the common and unique capabilities that affect innovation performance, innovation failures, and internal and vicarious learning. Second, the results suggest that complementarities between these four phenomena appear through complex interactions. This differs from prior studies, which often examined only one-to-one interactions. Thus, the results of certain activities can become the basis for others. For example, there may be a virtuous cycle in which internal and vicarious LFF are used in knowledge spillover transfers. This enhances the knowledge base, enabling firms to reduce the risk of failure in innovation projects and improve their innovation performance.

Practical implicationsThe findings of this study provide useful insights for managers. First, innovation performance, failures, and LFF strategies are interdependent and strengthen each other. SME managers should address them together, rather than separately, to develop more effective innovation strategies. Second, this study revealed a complementarity between internal and vicarious LFF. Managers should leverage this synergy and update internal routines to incorporate vicarious learning as a key activity. Third, the results showed innovation and LFF strategies are positively linked, while innovation is negatively linked with failures. We suggest managers use strategies that benefit from past failures. Learning from these failures may be an intangible asset that helps managers lower their efforts in seeking investments and funding. Finally, managers must consider SME-specific features and the subtleties of their seizing capabilities while managing innovation and LFF strategies. For example, not all aspects of seizing capabilities (such as internal R&D or knowledge employees) yield the same outcomes. Because SME resources are limited, managers should thoroughly analyze their firm’s capabilities before investing in DC.

Conclusion, limitation, and future avenues for researchConclusionThis study explores the complementarity between innovation performance, innovation failures, and learning from failures in Canadian manufacturing SMEs. It also examines the conditions needed for complementarity to occur. To do this, we used the microfoundations perspective of Dynamic Capabilities (DC). This perspective focuses on how organizations manage their capabilities and resources to create new value in changing environments (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2020). Following Teece (2007), we grouped the determinants of innovation performance, failures, and internal and vicarious learning from innovation failures into three DC components: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities.

The estimation of the multi-response model provided evidence on two main aspects: the relationships among the four dependent variables (innovation performance, failures, and learning from innovation failures, both internal and vicarious) and the effects of several explanatory variables on these outcomes. The results indicate that innovation performance and strategies for learning from innovation failures are closely linked. This finding is consistent with previous research, which identifies complementarity effects between innovation performance and strategies for learning from experienced innovation failures (Carmeli et al., 2012; Rhaiem and Amara, 2021; Shaik et al., 2023). Prior studies have primarily examined internal learning (Tucker & Edmondson, 2003; Carmeli, 2007; Shaik et al., 2023) and, to a lesser extent, vicarious learning (Bledow et al., 2017; Kim and Miner, 2007), often overlooking the potential complementarity between these two learning modes (Carmeli and Dothan, 2017; Antonacopoulou & Sheaffer, 2014). The present study clarifies the relationship between internal and vicarious learning from failure (LFF), demonstrating that engagement in one mode can benefit the other. Additionally, the results reveal a negative correlation between innovation performance and innovation abandonment, supporting research that identifies a negative relationship between innovation and failure. In this context, failures do not necessarily lead to organizational renewal, as firms often attribute these failures to uncontrollable events or factors beyond their internal analysis (Kc et al., 2013; Kim and Lee, 2020).

The findings regarding explanatory variables reveal that the dynamic capabilities of SMEs have varying degrees of influence on the dependent variables. Unlike previous studies that have overlooked the significance of firms’ informational capabilities (Harvey, 2025; Kim and Lee, 2020), this research emphasizes the knowledge acquisition process as a means to assess SMEs’ sensing capabilities. This process is widely recognized as essential for learning from failures (Zollo and Winter, 2002; Harvey, 2025). The study examines three specific sensing capabilities: internal knowledge search, external knowledge search, and social capital. The findings suggest that both innovation and learning from failure (LFF) are contingent on a firm’s relational activities, particularly those involving knowledge search. This observation is consistent with Social Learning Theory (SLT) (Bandura, 1977), which posits that LFF is facilitated through relational human interactions (Gu et al., 2013; Rhaiem and Halilem, 2023). Consequently, the development of sensing capabilities, including internal and external knowledge search and social capital, supports LFF activities and improves innovation performance.

For seizing capabilities, we found that cognitive seizing capabilities (psychological safety and trust) are influential on innovation performance, failures, and internal LFF. Feeling psychologically safe at work encourages innovation, while trust reduces the likelihood of failure. This finding aligns with previous studies, which suggest that a firm’s willingness to invest resources in structures and routines that promote a safe and trustworthy workplace leads to higher performance in terms of learning and innovation (Chirumalla, 2021; Hutton et al., 2021; Eldor et al., 2023). Moreover, our findings indicate that SME’s absorptive capacity, as measured by internal R&D investments and knowledge employees, is a valuable seizing capability for SMEs. This result aligns with the stream of studies emphasizing the positive relationship between AC and innovation (Flor et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2021), as well as between AC and organizational learning (Naqshbandi and Tabche, 2018; Darwish et al., 2020). Finally, the findings of our study show that reconfiguring capabilities, as measured by organizational support, are not associated with internal, LFF. This is in contrast with Carmeli and Sheaffer (2008), who showed that learning leadership and internal learning are positively related. Further empirical studies are needed to clarify the impact of organizational support on LFF strategies.

Limitations and future avenues for researchThis study has a number of limitations that create opportunities for future research. First, it only considers dynamic capabilities to explain the four phenomena under study. It would be helpful to expand our framework by adding more microfoundations of DC. Second, future research could capture external knowledge search with more advanced measures, such as breadth (variety in external sources) and depth (intensity of use). This would provide a clearer picture of LFF, and the innovation strategies employed by SMEs. Third, the empirical analysis is based on cross-sectional data, which may cause an endogeneity issue. A longitudinal research design is recommended to address this. Finally, we used a correlational method to explain the synergies between the four processes. We note possible interactions between the three components of DC in SMEs. Therefore, it would be valuable to test our results using a configurational method, such as fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). This would help capture synergies among microfoundations of DC and identify different pathways leading to the same outcome.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNabil Amara: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. Khalil Rhaiem: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Norrin Halilem: Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Operational definitions and descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables.

| Measure | Sub-items | Tolerance * | Cronbach’s α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEPENDENT VARIABLES: | |||||

| Innovation performance [PERF] | Measured as the percentage of the turnover that firms generated from products that were new or significantly improved during the last 3 years preceding the survey. | ||||

| Abandon [ABAND] | Continuous variable measured by the total number of innovation activities abandoned over the last 3 years preceding the survey. | ||||

| Internal learning [LEARN] | Measured as weighted index on a Likert scale of agreement ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often of the internal learning, over the last 3 years preceding the survey. |

| 0.76 | 0.714 | |

| Vicarious learning [VICAR] | Measured on a Likert scale of agreement ranging from 1 = Disagree to 5 = Strongly agree regarding external learning, in the following statement: |

| |||

| INDEPENDENT CONTINUOUS VARIABLES | |||||

| Knowledge employees [KNOEMP] | Measured as the percentage of the total number of employees working in the firm in R&D. Because of the highly asymmetric distribution of this variable, a square root transformation was applied to reduce the degree of skewness. | ||||

| Intellectual Property Protection [PROP] | Measured as an additive index on several different intellectual protection methods used for maintaining or increasing the competitiveness of product or process innovations introduced during the last 3 years preceding the survey in the following 8 formal legal forms: |

| 0.73 | ||

| Psychological Safety [PSY] | Measured as a weighted index on a Likert agreement scale ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often. |

| 0.67 | 60.3 | |

| Organizational support [SUPPO] | Measured as a weighted index on a Likert scale of agreement ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often, in the following 3 sub-items: |

| 0.55 | 71.1 | |

| Trust [TRUST] | Measured as a weighted index on a Likert scale of agreement ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often, in the following 4 sub-items: |

| 0.80 | 66.7 | |

| Social capital [KSOCIAL] | Measured as a weighted index on a Likert scale of agreement ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often, in the following 5 sub-items: |

| 0.65 | 67.5 | |

| Firm’s size [LNSIZE] | Continuous variable measured by the total number of employees in the firm in 2009. Because of the highly asymmetric distribution of this variable, a logarithmic transformation was applied to reduce the degree of skewness. | ||||

| INDEPENDENT CATEGORICAL VARIABLES | |||||

| Internal R&D [IRD] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ when the firm has internal R&D activities and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Internal sources [INTSCE] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used an internal source of information and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Suppliers [SUPPL] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from suppliers’ sources and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Clients [CLIENT] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from clients’ sources and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Government institutions, research labs [GVT &LABS] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from government, institutions, or research lab sources and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Universities [UNIVERS] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from a university source and coded ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Technical, industry, or service standards [STAND] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from technical industry or service standards source and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Scientific literature and professional publications [PUBLICA] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from scientific literature and professional publications source and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Professional and sectorial associations [ASSOC] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ if the firm used information from professional and sectorial associations sources and ‘0’ if not. | ||||

| Subsidiary group [SUBSID] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ when the firm is part of a group. | ||||

| Technology intensiveness [TECHINT] | Dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ when the firm operates in a High or Medium technology-intensive sector and ‘0’ when operating in a Low technology-intensive sector. | ||||

Note: The total number of observations is 436.

When at least one dependent variable is categorical, the asymptotic covariance matrix for the vector of sample statistics S is estimated using the limited information likelihood approach of Muthén (1984) and the weighted matrix W, which is used as an estimate of S, is a diagonal matrix using the estimated variances of the S elements (see Muthén et al., 1997). More technical details about the WLSMV estimator are provided in Muthén (1998–2004: 17–20).