While the importance of buyer transparency in supplier innovation has been recognized, its underlying mechanisms remain underexplored. Drawing on the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) framework, this study examines the mechanism through which buyer transparency—conceptualized as operations and strategy transparency—affects supplier innovation. The overall measurement model, including a newly developed multidimensional scale of buyer transparency, was validated through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Finally, survey data from 334 Chinese manufacturing suppliers were analyzed using hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypotheses. The results reveal that buyer transparency (opportunity) does not directly enhance supplier innovation. Rather, it does so conditionally through suppliers’ absorptive capacity (ability), customer orientation, and digital trust (motivation). By refining the conceptualization and measurement of buyer transparency, integrating digital trust into the open innovation framework, and empirically examining the contingent role of supplier-side factors, this study advances the literature on supply chain management and open innovation.

In today's rapidly evolving and highly competitive global market, innovation has become a critical driver for firms to achieve and sustain long-term competitive advantage (Algarni et al., 2023; Mehralian et al., 2024; Parra-Requena et al., 2020). However, firms increasingly recognize that in isolation, innovation alone is no longer sufficient to cope with market uncertainty and complexity (Lou et al., 2022). Consequently, many are turning to external resources, particularly by involving suppliers in their innovation processes and relying on inter-organizational collaboration to improve innovation quality and responsiveness (Jean et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017). Against this backdrop, a key issue in supply chain management and open innovation research is how buyers can effectively stimulate supplier innovation (Inemek & Matthyssens, 2013; Wei & Sheng, 2023; Wei et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023; Zhang & Li, 2023).

Buyer transparency—a supplier’s subjective perception of being informed about the relevant actions and properties of the buyer in the interactions—is considered a potential enabler of knowledge exchange (Eggert & Helm, 2003). Transparency helps mitigate information asymmetry, allowing suppliers to better understand customer needs and market dynamics, thereby optimizing their innovation strategies (Lamming et al., 2004). However, both practice and research reveal that transparency does not always produce positive outcomes. While some suppliers leverage buyer-shared information for collaborative innovation (Cerchione & Esposito, 2016), others fail to translate such information into tangible results due to insufficient capability or lack of motivation, sometimes resulting in project delays and resource waste (Paulraj et al., 2025). Thus, although buyer transparency is necessary to foster supplier innovation, it is not sufficient on its own.

Most studies have focused on buyer-driven mechanisms, such as investment, contractual governance, and capability building (Perols et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2005). Few pay attention to suppliers’ behavioral foundations as “information receivers.” To our knowledge, these studies have not sufficiently explained why suppliers respond differently to the same transparency practices, nor have they explored how different types of transparency (e.g., operations versus strategy) may follow distinct impact paths. Furthermore, traditional theoretical frameworks, such as the resource-based view or dynamic capability theory, often examine motivation or capability mechanisms in isolation, lacking an integrative perspective that explains how motivation, opportunity, and ability jointly influence suppliers’ innovative responses.

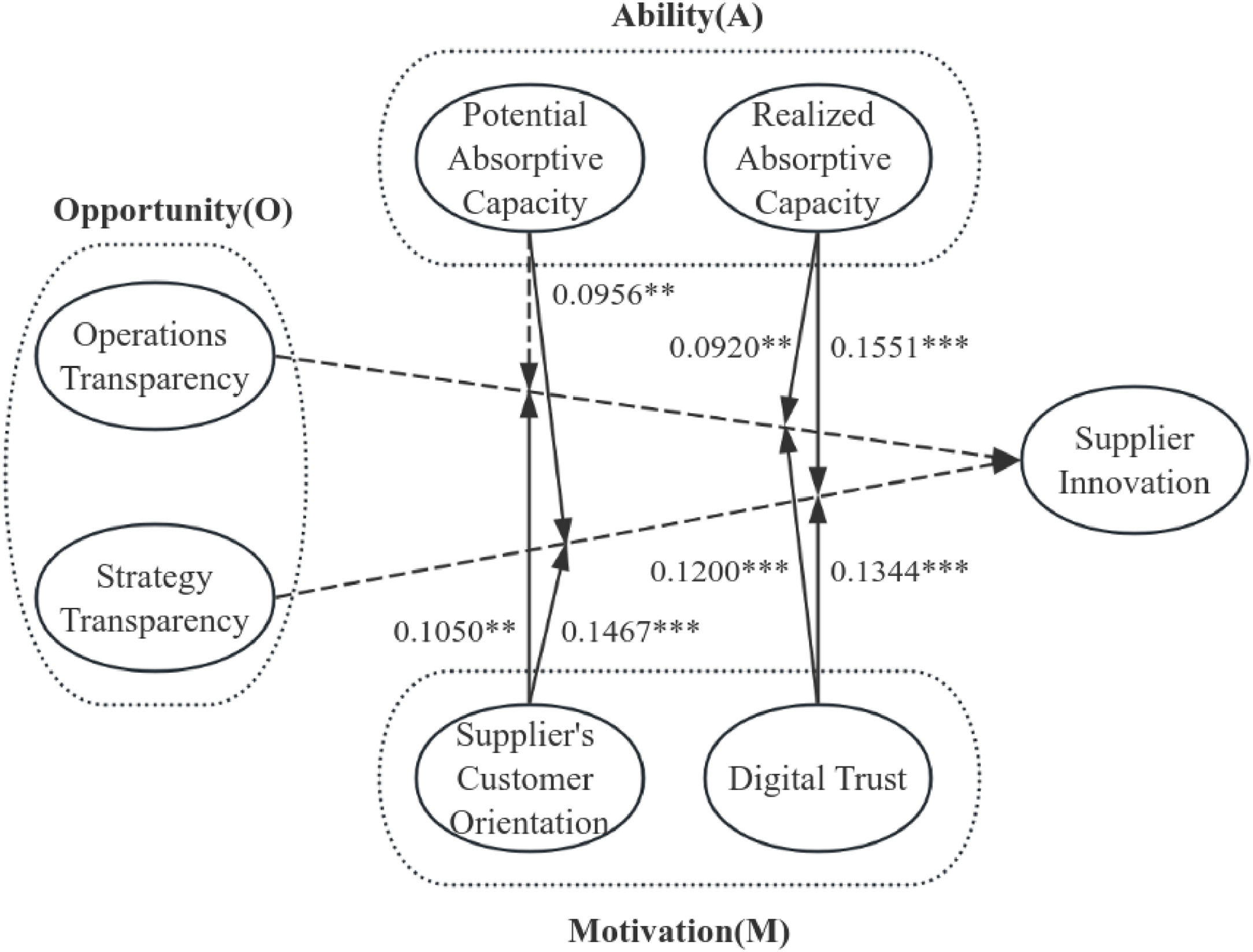

Addressing these gaps, this study introduces the Motivation–Opportunity–Ability (MOA) framework to theorize suppliers’ behavioral responses to buyer transparency. In this framework, buyer transparency provides the opportunity for suppliers to access external innovation-related information. The suppliers’ absorptive capacity (ACAP) represents their ability to transform that information into innovation. ACAP is further divided into potential absorptive capacity (PACAP), representing the ability to identify, acquire, and assimilate new knowledge, and realized absorptive capacity (RACAP), representing the ability to transform and apply that knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002). Motivation is captured by digital trust and customer orientation. In increasingly digitalized supply chains, suppliers’ trust in digital tools (e.g., enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems and industrial Internet-of-Things (IoT) platforms) critically influences their willingness to use buyer-disclosed information (Chen et al., 2025). Customer orientation reflects whether suppliers are intrinsically motivated to understand buyer needs and pursue innovation accordingly (Jean et al., 2017). The theoretical lens of the MOA framework not only integrates key perspectives from the resource-based view, knowledge management, and dynamic capability theory but also aligns with the practical realities faced by Chinese manufacturing suppliers amid digital transformation and the restructuring of global value chains.

This study specifically aims to address the following research question: “How does buyer transparency stimulate supplier innovation under different conditions of supplier ability and motivation?” To answer this question, we construct and empirically test a theoretical model based on the MOA framework, systematically analyzing the heterogeneous effects of operations and strategy transparency under various moderating mechanisms. Then, using structured survey data from 334 Chinese manufacturing suppliers, we employ an empirical, quantitative research design. Hypotheses are tested using exploratory factor (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and hierarchical regression analyses (HRA), with a focus on the moderating roles of ACAP, customer orientation, and digital trust.

This study contributes to the supply chain management and open innovation literature in several ways. First, it reconceptualizes buyer transparency not merely as an efficiency-oriented governance tool but as a strategic enabler of inter-organizational innovation. By developing a multidimensional structure of transparency comprising operations and strategy dimensions, and a supplier-oriented measurement scale, we uncover the differentiated effects of transparency on innovation. Further, we highlight the strategic importance of selective transparency in digitally complex supply chains. Second, by applying the MOA framework, the study shifts the focus from buyer-driven mechanisms to a supplier response perspective. It demonstrates that the effectiveness of transparency depends on suppliers’ ACAP and innovation motivation (e.g., customer orientation and digital trust). Third, introducing digital trust into the digitally mediated buyer-supplier interface, we identify it as a critical behavioral mechanism, particularly in emerging economies characterized by uneven levels of institutional trust and digital readiness. Finally, we extend the MOA framework from individual and intra-organizational settings to inter-organizational innovation, offering an integrated behavioral lens to understand when buyer practices can be translated into supplier innovation.

Theoretical background and hypothesis developmentSupplier innovationSupplier innovation plays a vital role in inter-organizational value co-creation, allowing suppliers to contribute added value to upstream buyers through novel knowledge, technologies, and processes (Pihlajamaa et al., 2019). Early research defined supplier innovation as “the ability to use new or improved products, services, or processes relative to the supplier’s current activities” (Noordhoff et al., 2011). Scholars have explored its drivers from multiple perspectives, including knowledge transfer (Sikombe & Phiri, 2019), collaborative relationships (Inemek & Matthyssens, 2013), information technology (IT) resources (Jean et al., 2017), and network structure (Potter & Wilhelm, 2020). Collectively, these studies emphasize that innovation is not an isolated activity but rather the result of inter-organizational resource integration and knowledge flows (Lou et al., 2022).

From the knowledge-based view, innovation generation is generally considered an information-intensive activity that requires continuous investment in new knowledge and capabilities (Sang et al., 2024). Buyer transparency helps reduce information asymmetry and promote knowledge flow, offering suppliers opportunities for learning and enhancing their innovation potential. However, transparency alone is insufficient; its impact depends on how suppliers interpret, assimilate, and apply the information they receive.

Deeply embedded social or relational ties often foster close interactions among individual members, thereby providing more effective channels for tacit knowledge transfer and exchange (Aminoff & Tanskanen, 2013; Pihlajamaa et al., 2019). In China, the guanxi culture plays a unique role in supplier innovation. It reinforces suppliers’ sense of reciprocity: when suppliers anticipate that their innovation investments will lead to long-term collaboration or strategic resource support, they tend to prioritize resource allocation for buyers with whom they have close relationships (Schiele, 2012). Some customers are even regarded as “priority customers,” thereby gaining competitive advantages in resource acquisition and innovation collaboration.

The recent wave of digital transformation has increased the complexity of supply chain ecosystems, making digital trust—a supplier’s confidence in the reliability of the buyer’s information systems, data security, and platform infrastructure (Kluiters et al., 2023)—a new determinant of collaborative innovation. When suppliers trust the digital platforms’ security and accuracy, and simultaneously build strong social trust through long-term cooperation, they are more willing to share knowledge and engage in joint development efforts. This trust amplifies transparency’s positive effects on innovation (Aminoff & Tanskanen, 2013).

Researchers increasingly view supplier innovation as a multidimensional process rather than a single capability. For instance, Pihlajamaa et al. (2019) decomposed it into a three-dimensional structure. First, suppliers must possess the ability to generate new knowledge and technologies. Second, their innovation activities should align with buyer needs to ensure that the innovation outcomes directly contribute to the buyer’s value creation. Finally, suppliers must be willing to share their innovations with buyers to achieve resource integration and synergistic value enhancement.

Drawing on these perspectives, this study defines supplier innovation as the process through which suppliers acquire, develop, and apply new knowledge and technologies (innovation capability), engage in targeted innovation based on buyer needs and market trends (innovation relevance), and share innovation outcomes within supply chain collaborations (innovation sharing) to enhance their competitiveness and create greater value for buyers. This comprehensive definition captures both the technical and relational dimensions of innovation and provides the basis for our hypothesis development.

Buyer transparencyBuyer-supplier relationship transparency is widely recognized as a critical factor in strengthening supply chain collaboration, enhancing focal firm competitiveness, and engendering knowledge capital (Kumar & Yakhlef, 2016). Early definitions of transparency emphasized partners’ subjective perceptions of behavioral openness and the degree of information sharing during collaboration (Eggert & Helm, 2003), often involving disclosures of technological knowledge, business data, and strategic intentions (Lamming et al., 2004). Su et al. (2013) broadened this view, suggesting that relationship transparency also includes visibility into organizational vision, values, strategic intent, and the relational climate, such as trust, dependence, and cooperation.

While relationship transparency has attracted growing interest, most studies have focused on supplier transparency, representing the extent to which buyers access supplier information (e.g., financial health, technical capabilities, or capacity constraints) (Eggert & Helm, 2003; Kumar & Yakhlef, 2016). Meanwhile, buyer transparency has received comparatively limited attention, despite its importance in today’s digitalized and globally connected supply chains. Resource-rich buyers often act as innovation orchestrators, disseminating market insights, technical standards, and performance expectations through digital tools and relational mechanisms (Kim et al., 2015; Sikombe & Phiri, 2019). This not only shapes suppliers’ expectations but also influences their learning behaviors and innovation investments.

The evolving literature has classified transparency in various ways (Bai & Sarkis, 2020; Hultman & Axelsson, 2007; Mol, 2015). Hofstede (2003b) categorized transparency into three types—history, operations, and strategy transparencies—based on whether the disclosed information pertains to the past, present, or future, respectively. Drawing from this distinction and applying it to supply chain innovation, this study focuses on two forward-looking forms of buyer transparency: operations and strategy transparencies.

In buyer-supplier relationships, operations transparency refers to the buyer’s disclosure of operational and product-related information, enabling suppliers to better understand demand, optimize resource allocation, and mitigate supply chain risks (Kumar & Yakhlef, 2016). Digital technologies such as IoT, blockchain, and data analytics support real-time updates, allowing suppliers to dynamically monitor supply chain conditions and adjust strategies accordingly. Conversely, strategy transparency involves the buyer sharing long-term goals, developmental trajectories, and market roadmaps to facilitate suppliers’ strategic alignment and foster deeper collaboration (Eggert & Helm, 2003; Su et al., 2013). These two transparency dimensions differ not only in content but also in their cognitive and motivational implications for suppliers. While operations transparency enhances coordination in production and delivery, strategy transparency promotes strategic alignment and forward-looking innovation planning (Theuvsen, 2004).

The literature often uses key concepts such as visibility, traceability, and information disclosure as synonyms for transparency. However, visibility refers to an organization’s efforts to collect and systematically organize supply-related information primarily for internal use (Sodhi & Tang, 2019). Traceability encompasses a broad range of organizational practices and technological systems necessary for effective information integration (Ringsberg, 2014). Information disclosure emphasizes the exchange of operational, market, and demand data among supply chain members, focusing on the accessibility of information without necessarily addressing its interpretation or strategic significance (Schnackenberg et al., 2021). Meanwhile, transparency goes beyond mere information sharing; it encompasses clarity, timeliness, and strategic alignment, influencing suppliers’ perception, interpretation, and application of shared information (Wognum et al., 2011). This influences their innovation behavior.

The MOA frameworkTo systematically investigate when buyer transparency stimulates supplier innovation, this study adopts the MOA framework as its theoretical foundation. Originally proposed by MacInnis and Jaworski (1989) in consumer behavior research to explain individuals’ responses to marketing stimuli, the MOA framework has since been widely applied in various fields such as knowledge management (Argote et al., 2003), operations management (Siemsen et al., 2008), and management studies (Dahlin et al., 2018).

The MOA framework posits that behavior, whether individual or organizational, emerges from the interaction of motivation, opportunity, and ability. Motivation refers to the willingness of an individual or organization to perform a task (Elbaz et al., 2018). Opportunity involves environmental factors that facilitate or constrain behavior (Siemsen et al., 2008). Ability reflects whether an organization possesses the necessary knowledge, skills, and resources to undertake specific actions (Fadel & Durcikova, 2014). These three elements do not function independently; rather, they interact dynamically to determine the occurrence and effectiveness of behavior (Wang et al., 2013).

Although initially developed to explain behavior at the individual level, the MOA framework’s adaptability enables it to effectively interpret complex inter-organizational interactions. In supply chain management, it offers a powerful lens for understanding when and how buyer transparency can stimulate supplier innovation. By integrating diverse perspectives, such as the resource-based view, knowledge transfer, and dynamic capability theory, the framework helps clarify the boundary conditions of transparency-based incentives and reveals the behavioral logic behind supplier innovation responses.

We conceptualize opportunity as buyer transparency, comprising two dimensions: operations and strategy transparencies. Transparency fosters an information-rich environment (Bai & Sarkis, 2020), providing suppliers with foundational knowledge to identify market demand and adjust technological trajectories. However, information alone does not guarantee innovation; its effectiveness depends on whether the supplier has sufficient ACAP and motivation to apply it.

Ability determines whether suppliers can effectively absorb and utilize the information provided by buyer transparency. ACAP captures a supplier’s potential to transform transparent information. ACAP enhances both the accessibility and applicability of knowledge, thereby amplifying the effect of transparency on innovation performance. Specifically, PACAP enables suppliers to identify, acquire, and assimilate transparent information and knowledge from buyers, while RACAP reflects their ability to transform and apply such knowledge into innovative outcomes (Božič & Dimovski, 2019).

Motivation reflects whether suppliers are willing to leverage transparent information to drive innovation (Hong & Gajendran, 2018). Two key factors that capture supplier motivation are customer orientation and digital trust. Customer-oriented suppliers proactively collect and analyze buyer needs (Jean et al., 2017), viewing transparency as a valuable source of innovation and align their product or technological development accordingly. In highly digitized supply chains, suppliers rely on digital platforms for information exchange. Their trust in the platform’s security, data accuracy, and reliability influences their willingness to act on the shared information. Digital trust reduces concerns over information distortion and fosters cooperative intent (Chen et al., 2025).

The MOA framework’s unique value is its integration of previously fragmented perspectives from the resource-based view, knowledge transfer, and dynamic capability theory, while also demonstrating applicability in the highly heterogeneous context of Chinese manufacturing. Here, interfirm information asymmetry is pronounced and digitalization levels vary. Transparency provides external informational opportunities. However, whether these lead to action depends on supplier readiness—specifically, their motivation and ability. The MOA framework captures this variation, and thus, better explains the effects of buyer practices.

In conclusion, the MOA framework offers a structured lens to examine buyer transparency and provides a solid theoretical foundation for understanding supplier innovation mechanisms in the era of digitalization and globalization.

Conceptual model and hypothesis developmentBuyer transparency as an opportunityWe define buyer transparency as the supplier’s perception of the extent of the buyer’s proactive sharing of operational and strategic information. Operations transparency refers to the communication of product, process, and scheduling information, whereas strategy transparency encompasses the sharing of long-term goals, development plans, and market trends (Hofstede, 2003a, 2003b).

The knowledge-based view posits that innovation relies on the acquisition and integration of high-quality knowledge (Grant, 1996). Here, transparency serves as a critical channel for facilitating such knowledge acquisition. Operations transparency enables suppliers to precisely align with buyer needs, optimize research and development (R&D) processes, and enhance technological capabilities (Jean et al., 2012). Extant research indicates that innovation-related information disclosed by buyers can significantly increase suppliers’ R&D investment and patent output (Luo et al., 2023). High-clarity information allows suppliers to accurately understand buyer needs, thereby preventing resource misallocation. Meanwhile, highly timely information helps suppliers swiftly respond to market changes and seize innovation opportunities.

Furthermore, buyer transparency in strategic planning can enhance supplier innovation. For example, buyers can share long-term goals through supplier days (Perrons, 2009) or disclose technology roadmaps to key suppliers (Pihlajamaa et al., 2019). This initiative enables suppliers to adjust their R&D directions based on market trends, ensuring the foresight and relevance of their innovation efforts. Meanwhile, suppliers can set clear innovation objectives accordingly and collaborate with buyers in developing new technologies and products, thereby improving cooperation efficiency (Luo et al., 2023). In this process, a high level of strategy transparency encourages suppliers to share innovation outcomes and facilitates bidirectional knowledge flow through digital platforms, fostering deep collaboration and co-innovation.

When a powerful buyer does not share future strategies or provides incomplete operational information to suppliers, the latter may struggle to determine potential outcomes, heightening their perceptions of ambiguity and relational risk (Venkatraman et al., 2006). This uncertainty reduces suppliers' perceived loyalty to the buyer relationship and negatively impacts the relevance of their innovations to the buyer and their willingness to share innovations (Ma et al., 2021).

While most studies highlight the positive role of transparency, recent research suggests its effects may vary depending on supplier characteristics and the relational context (Paulraj et al., 2025). When information is complex or suppliers are not well-prepared, excessive or unclear transparency may instead increase uncertainty and strategic risk (Eggert & Helm, 2003; Perotti et al., 2022). Moreover, the impact of transparency on innovation may be indirect, contingent on the supplier’s capability base or motivational orientation. Therefore, while we consider that higher levels of operations and strategy transparency can stimulate supplier innovation, this relationship may be subject to boundary conditions, particularly under varying levels of ability and motivation.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H1a: Higher operations transparency leads to greater supplier innovation.

H1b: Higher strategy transparency leads to greater supplier innovation.

Next, we explore the factors that may strengthen or weaken this relationship.

Absorptive capacity as an abilityIn dynamic and turbulent environments, knowledge is a critical resource for firms to create value, gain access to, and sustain competitive advantages (Al-Omoush et al., 2020; Innes, 2024). Buyer transparency provides suppliers with abundant information and knowledge sources, creating opportunities to stimulate supplier innovation. However, merely acquiring information is not sufficient to drive innovation; suppliers must possess the necessary capabilities to absorb and utilize this knowledge. ACAP is a key factor in enabling recipients to leverage external knowledge (Kim et al., 2015). Opportunities can only be fully realized when suppliers possess sufficient ACAP to utilize this information (Božič & Dimovski, 2019). Therefore, based on the MOA framework, this study identifies suppliers’ ACAP as a key capability variable linking buyer transparency to supplier innovation.

Originally a macroeconomic concept, ACAP refers to an entity’s ability to absorb and utilize external knowledge and resources (Murovec & Prodan, 2009). Cohen and Levinthal (1990) defined it as an organization’s ability to recognize, assimilate, and apply new external knowledge for commercial purposes, identifying it as a key innovation driver. Zahra and George (2002) further refined this concept, defining ACAP as a set of routines and processes through which firms acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge to enhance dynamic capabilities and sustain competitive advantage. These four processes form the structural foundation of ACAP (Camisón & Forés, 2010). This study adopts Zahra and George's (2002) classification, distinguishing between PACAP (acquisition and assimilation) and RACAP (transformation and exploitation). PACAP reflects a firm’s ability to acquire and integrate external knowledge to expand its knowledge base (Božič & Dimovski, 2019). RACAP represents the transformation and application of knowledge to enhance innovation (Ali et al., 2016; Božič & Dimovski, 2019; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2014).

According to organizational learning theory, achieving innovation requires firms to recognize the value of new knowledge and apply it to their operations (Kostopoulos et al., 2011). In the digital era, suppliers increasingly rely on external knowledge to overcome internal resource constraints. Operations transparency conveys relatively structured and standardized information, such as order status, capacity data, and quality specifications, that may not demand highly complex cognitive processing at the basic operational level. Nevertheless, such information can still serve as foundational input for process optimization, identifying production bottlenecks, and adjusting technical configurations in the context of innovation. When suppliers possess stronger PACAP, they are more likely to rapidly comprehend and integrate transparent information from buyers, and effectively align it with their internal knowledge base (Zapata-Cantu et al., 2020). By leveraging technologies such as big data analytics and supply chain collaboration platforms, suppliers can better identify buyer demands, filter and process external information, and accelerate knowledge application, ultimately enhancing innovation success (Algarni et al., 2023).

H2a: The greater the supplier’s PACAP, the stronger the positive influence of operations transparency on supplier innovation.

H2b: The greater the supplier's PACAP, the stronger the positive influence of strategy transparency on supplier innovation.

Although PACAP facilitates suppliers’ knowledge acquisition, its impact on innovation remains limited if suppliers lack the capability to transform knowledge into innovation (Ali et al., 2016). RACAP represents a firm’s ability to transform, reconfigure, and apply external knowledge to develop new products, optimize processes, or improve services (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2014). Suppliers with high RACAP can efficiently assimilate the knowledge provided by the buyer and rapidly translate it into innovative outcomes, thereby enhancing innovation efficiency (Sheng & Chien, 2016). In China’s manufacturing sector, firms generally emphasize long-term collaborative relationships. These provide a more stable foundation for realizing RACAP, as the guanxi culture reinforces knowledge sharing and innovation willingness. Meanwhile, digital supply chain technologies (e.g., smart manufacturing and industrial IoT) accelerate knowledge transformation. They enable high RACAP suppliers to efficiently apply new knowledge in R&D, production, and operations, thereby improving the alignment between innovation and buyer needs (Algarni et al., 2023).

H3a: The greater the supplier's RACAP, the stronger the positive influence of operations transparency on supplier innovation.

H3b: The greater the supplier's RACAP, the stronger the positive influence of strategy transparency on supplier innovation.

In supply chain collaboration, even if suppliers can absorb information and knowledge from buyers, it does not necessarily mean that they are willing (i.e., motivated) to learn from buyers. Selnes and Sallis (2003) noted that “learning in customer-supplier relationships cannot be mandated; it depends on both parties’ willingness to cooperate in joint activities”. Therefore, assuming that all suppliers require transparent information and knowledge from buyers may not be reasonable. Suppliers must have sufficient motivation to absorb the information and knowledge provided by buyers, consistent with the MOA framework.

Suppliers’ learning motivation often stems from their strategic orientation. Customer orientation reflects a firm’s strategic approach in the market, whereby business decisions are guided by a continuous focus on customer needs (Jean et al., 2017). Gatignon and Xuereb (1997) argued that customer-oriented firms can identify, analyze, and proactively respond to customer demands, a characteristic closely linked to innovation success. Customer-oriented suppliers not only actively collect and disseminate market information but also effectively reallocate internal resources to deliver innovative solutions that align with buyer expectations (Narver et al., 2004). Suppliers can also leverage digital technologies such as ERP, customer relationship management (CRM), and big data analytics to acquire buyer needs in real-time and utilize intelligent algorithms to predict market trends. This technological empowerment enables customer-oriented suppliers to more accurately interpret buyer transparency and swiftly adjust their innovation strategies, thereby more effectively driving innovation (Im & Workman, 2004).

In China’s manufacturing industry, customer orientation is not only a corporate strategy but also deeply embedded in the business culture. Chinese firms emphasize long-term cooperative relationships, with suppliers typically maintaining stable collaboration networks by meeting buyers' needs (Wang et al., 2013). Within this cultural framework, suppliers are more inclined to adjust their business models based on buyer transparency to ensure strategic alignment with buyers. Digital tools further enhance this alignment capability, enabling suppliers to quickly adapt to market changes and improve the efficiency and relevance of innovation. For example, real-time data sharing on digital platforms allows suppliers to accurately analyze buyers’ long-term strategic directions, optimizing product development and technological innovation.

Overall, besides being more adept at capturing buyer needs, customer-oriented suppliers can also enhance the success rate and market adaptability of innovation through effective knowledge sharing and collaborative innovation. Conversely, suppliers without a customer orientation tend to focus more on their business models and neglect the information provided by buyers. Even with high transparency, these suppliers struggle to transform it into an innovation-driving force. Therefore, this study argues that customer orientation, as an intrinsic motivation, amplifies the positive effect of buyer transparency on supplier innovation.

H4a: The greater the supplier's customer orientation, the stronger the positive influence of operations transparency on supplier innovation.

H4b: The greater the supplier's customer orientation, the stronger the positive influence of strategy transparency on supplier innovation.

In the digital supply chain environment, digital trust among suppliers is a crucial motivation for accepting buyer transparency and transforming it into innovative outcomes. Traditional trust is typically based on long-term cooperation and social capital. Traditional trust between organizations can be defined as “one party’s willingness to be influenced by the actions of the other party.” However, driven by Industry 4.0 technologies, trust has gradually shifted towards technology-driven digital trust (Kluiters et al., 2023). Digital trust encompasses the supplier’s trust in the buyer’s digital platforms, information systems, and data-sharing mechanisms (Mubarak & Petraite, 2020), including data accuracy, system security, platform reliability, and transaction transparency. This affects the supplier’s willingness to accept transparent information and determines whether they are willing to innovate based on that information. With the development of technologies such as blockchain, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence, digital trust has become a core element in reducing transaction uncertainty, promoting supply chain collaboration, and enhancing inter-organizational cooperation efficiency.

Digital trust strengthens buyer transparency’s role in stimulating supplier innovation by promoting efficient collaboration, accelerating knowledge flow, and reducing monitoring costs (Chen et al., 2025). In high digital trust environments, suppliers are more willing to engage in deeper interactions with buyers, sharing technological pathways, market trends, and strategic plans, thereby enhancing innovation efficiency and accuracy (Terhorst et al., 2024). Additionally, digital trust reduces information asymmetry in collaborations, allowing suppliers to acquire, integrate, and utilize external knowledge with low risk (Kmieciak, 2021; Mubarak & Petraite, 2020). Concurrently, digital trust lowers inter-organizational monitoring and coordination costs, smoothing knowledge flows (Brockman et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020) and promoting the formation of cross-organizational innovation networks. When suppliers have high trust in the buyer’s digital platform, their enthusiasm for information sharing and joint R&D significantly increases, accelerating the realization of innovation outcomes.

Essentially, in highly digitized supply chain environments, digital trust plays a key role in aligning supplier innovation with buyer needs. After trusting the real-time data, market forecasts, and demand analysis provided by the buyer, suppliers are more willing to adjust their R&D directions and product designs based on transparent information, improving the market adaptability of innovations (Espino-Rodríguez & Taha, 2022; Yeniyurt et al., 2014). This trust mechanism not only enhances the supply chain’s overall innovation capacity but also ensures that innovation outcomes better align with the buyer’s long-term strategic goals.

Furthermore, establishing digital trust enhances suppliers’ willingness to share knowledge with buyers (Terhorst et al., 2024) and increases their willingness to open up their technological resources. Cepa and Schildt (2019) noted that when an organization lacks trust in its business network and spatial environment, it tends to reduce or even avoid knowledge sharing with external stakeholders, negatively affecting knowledge inflows and outflows between organizations. However, digital trust ensures data security through blockchain technology, encryption protocols, and smart contracts, alleviating suppliers’ concerns about technological leaks and unfair collaboration (Kmieciak, 2021). When suppliers trust that buyers will not misuse shared information, they are more willing to open their technological resources, facilitating bidirectional knowledge flow and further reinforcing the stimulating effect of transparency on supplier innovation (Espino-Rodríguez & Taha, 2022). Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H5a: The greater the supplier's digital trust, the stronger the positive influence of operations transparency on supplier innovation.

H5b: The greater the supplier's digital trust, the stronger the positive influence of strategy transparency on supplier innovation.

Fig. 1 summarizes the conceptual model underpinning the research.

MethodologySampling and data collectionThis study investigates the impact of buyer transparency on supplier innovation, focusing on Chinese manufacturing suppliers. As the world’s largest manufacturing hub, China provides a valuable context due to its complex industrial chains that rely on supply chain coordination. The sector contributes nearly one-third of China's GDP, with suppliers acting as key innovation drivers. Ongoing digital transformation, fueled by government policy, competitive pressures, and rising consumer demand, further elevates the importance of transparency and collaboration in supplier innovation.

We adopt an empirical, quantitative approach using a structured survey that collects data from manufacturing firms in five Chinese provinces: Jiangsu, Guangdong, Shandong, Henan, and Shaanxi. These provinces represent different levels of industrial development and regional economic characteristics: Jiangsu and Guangdong, located in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta, respectively, are hubs of advanced manufacturing in China. Shandong, situated in the eastern region, has a moderately developed manufacturing sector. Henan, as a central heavy industrial base, is representative of supply chain integration. Finally, Shaanxi, the core of western China’s manufacturing industry, is undergoing industrial upgrading. This regional diversity helps mitigate the influence of location-specific factors on research findings (Zhang et al., 2020).

A random sample of 700 firms was drawn from economic development zone lists, focusing on enterprises engaged in component or module development with proprietary technologies. The sample covers a broad range of subsectors, including mechanical equipment, transportation, and electronics, which represent a significant share of China’s industrial output. Firms vary in size, ownership, and region, ensuring structural diversity and enhancing external validity within the Chinese context. Questionnaires were distributed via email and print, targeting senior personnel (e.g., supply chain managers and R&D directors) involved in buyer collaboration and innovation. Screening criteria ensured that respondents had at least three years of experience in supply chain collaboration and had participated in digital integration, transparency-related information exchange, or joint innovation initiatives.

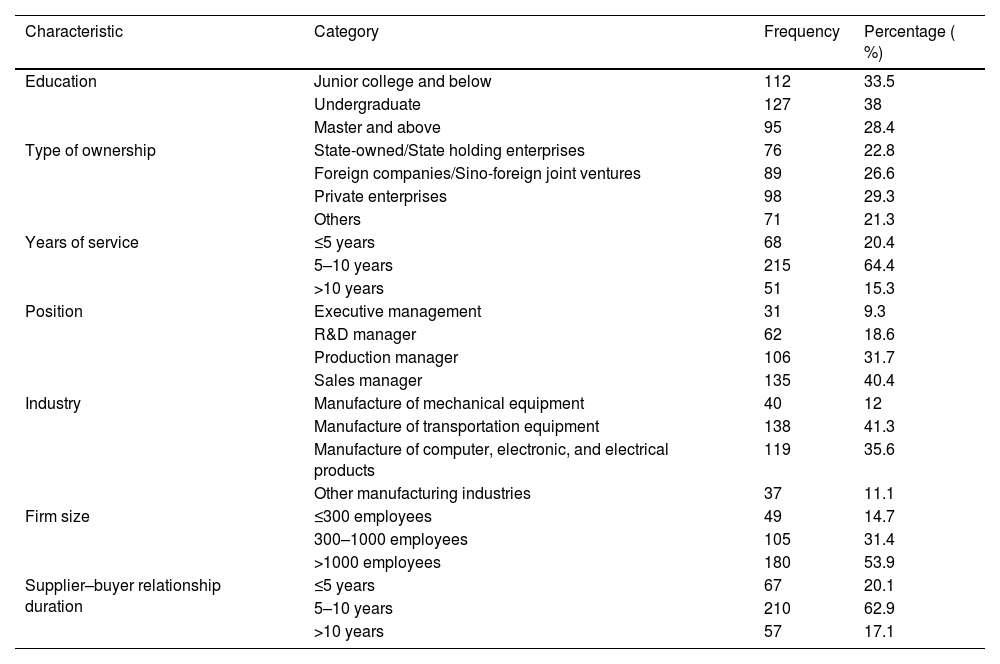

The survey, conducted from March to July 2024, yielded 468 responses from 700 distributed questionnaires. After excluding incomplete responses, 334 valid questionnaires were retained, resulting in an effective response rate of 71.37 %. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the sample.

The profiles of the interviewees and sample.

This study follows rigorous scale development and measurement procedures to ensure the questionnaire’s accuracy and scientific validity. Based on a comprehensive literature review, we adapted well-established scales to fit the research context. To eliminate ambiguity, we applied a translation-back translation process, where experts translated the scale from English to Chinese, followed by independent back-translation to ensure consistency. We then refined the questionnaire through expert interviews and a pilot test, leading to the final version. The questionnaire comprises 38 items across seven constructs, all measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”), as detailed in Table 2.

Measurement items.

| Measurement metrics | Sources |

|---|---|

| Operations transparency | |

| OT1. The key BUYERS provide us with demand and inventory information (e.g., product demand, quality standards, material requirements, and inventory levels) regarding the products they need us to produce. | Developed by the authors based on Hofstede (2003a, 2003b), Lamming et al. (2004), and Su et al. (2013) |

| OT2. The key BUYERS provide us with schedule and delivery information (e.g., order quantities, changes in orders, delivery timelines, logistics, and destinations). | |

| OT3. The key BUYERS provide us with information they have gathered regarding risks and changes within the supply chain (e.g., fluctuations in raw material prices, trends in order volume changes, plans for new product launches, geopolitical risks, and natural disaster risks). | |

| OT4. The key BUYERS provide us with technical and design information (e.g., product parameters, technical specifications, level of work in progress, and design drawings). | |

| Strategy transparency | |

| ST1. The key BUYERS provide us with their strategic plans and objectives (e.g., strategic goals, long-term plans, market positioning). | Developed by the authors based on Hofstede (2003a, 2003b), Lamming et al. (2004), and Su et al. (2013) |

| ST2. The key BUYERS provide us with market trends and industry dynamics (e.g., changes in market demand, competitive landscape, and emerging technologies). | |

| ST3. The key BUYERS provide us with their R&D directions and innovation goals (e.g., cost reduction, product improvement, process optimization, and new feature development). | |

| ST4. The key BUYERS provide us with their relevant data and big data analytics results (e.g., market data, production data, and quality data) along with data-sharing platforms, analytical tools, and technical support. | |

| ST5. The key BUYERS provide us with information about the relational atmosphere in which we are treated (e.g., power/dependence, trust/opportunism, cooperation/conflict, relational expectations, and closeness/distance situations). | |

| Potential absorptive capacity | |

| PACAP1. Searching for relevant external information is an everyday business in our organization. | Limaj and Bernroider's (2019) |

| PACAP2. Our employees are encouraged to identify and consider external information sources. | |

| PACAP3. We expect our employees to acquire relevant external information. | |

| PACAP4. Ideas and concepts obtained from external sources are quickly analyzed and shared. | |

| PACAP5. We work together across the organization to interpret and understand external information. | |

| PACAP6. In our organization, external information is quickly exchanged between business units. | |

| PACAP7. We regularly organize and conduct meetings to discuss new insights. | |

| Realized absorptive capacity | |

| RACAP1. Our employees have the ability to structure and use newly collected information. | Limaj and Bernroider's (2019) |

| RACAP2. Our employees are used to preparing newly collected information for further purposes and making it available. | |

| RACAP3. Our employees can integrate new information into their work. | |

| RACAP4. Our employees have immediate access to stored information (e.g., about new or changed guidelines or instructions). | |

| RACAP5. Our employees regularly engage in the development of prototypes or new concepts. | |

| RACAP6. Our employees apply new knowledge in the workplace to respond quickly to environment changes. | |

| Supplier’s customer orientation | |

| SCO1. We regularly meet key BUYERS to learn about their current and potential needs for new products. | Atuahene-Gima (2005) |

| SCO2. We constantly monitor and reinforce our understanding of the current and future needs of key BUYERS. | |

| SCO3. We have a thorough knowledge of emerging key BUYERS and their needs. | |

| SCO4. Information about current and future key BUYERS is integrated into our plans and strategies. | |

| SCO5. We regularly use research techniques such as focus groups, surveys, and observations to gather information about key BUYERS. | |

| SCO6. We have developed effective relationships with key BUYERS and suppliers to fully understand new technological developments that affect key BUYERS’ needs. | |

| SCO7. We systematically process and analyze key BUYERS' information to fully understand their implications for our business. | |

| Digital trust | |

| DT1. The digital platforms and information systems provided by the key BUYERS are reliable and effective in protecting our business from the risk of data security and privacy breaches. | Chen et al. (2025) |

| DT2. The key BUYERS share operational and strategic information with the best interests of our organization in mind and ensure fairness and transparency. | |

| DT3. The key BUYERS have sufficient technical and managerial capabilities to ensure the accuracy, security, and reliability of information on digital platforms to support innovative decision-making in our organization. | |

| Supplier innovation | |

| Supplier innovation value | Chang et al. (2014) and Im and Workman (2004) |

| SI1. Compared to other supplier firms, our components provide exceptional value. | |

| SI2. Compared to other supplier firms, our components demonstrate a unique approach to problem-solving. | |

| SI3. Compared to other supplier firms, our components better meet customer needs and expectations. | |

| SI4. Compared to other supplier firms, our components offer practical utility to customers. | |

| Supplier innovation contribution | Pulles et al. (2014) |

| SI5. We are willing to design new components/sub-assemblies or make changes to existing components/sub-assemblies for key BUYERS. | |

| SI6. We are willing to share key technical information with the key BUYERS. | |

| SI7. We have a high technical capability and are willing to use it for key BUYERS products. | |

| SI8. We can support collaborative processes in product development and process improvement. | |

| SI9. We are often proactive in proposing innovative solutions to key BUYERS. |

Supplier innovation comprises two dimensions: innovation value and innovation contribution. Innovation value, measured through innovation novelty and relevance, is based on Chang et al. (2014) and Im and Workman (2004), with context-specific modifications. Innovation contribution, drawing from Pulles et al. (2014), includes five items.

Buyer transparency, adapted from Hofstede (2003a, 2003b), Lamming et al. (2004), and Su et al. (2013), is divided into operations (four items) and strategy transparency (five items). Operations transparency covers demand and inventory information, order and delivery schedules, supply chain risk, and product specifications. Strategy transparency includes strategic planning, market trends, R&D directions, industry developments, and supply base management. Scale development involved construct definition, expert interviews, a pilot test, EFA, and CFA. The 119 responses used for EFA were collected during the pilot test phase and not included in the main dataset of 334 responses used for CFA and hypothesis testing. This ensures the independence of both analyses and enhances the robustness of the scale validation process. EFA was conducted using SPSS 27.0 on these 119 pilot responses, leading to the removal of low-loading items and yielding a stable measurement structure (KMO = 0.881, Bartlett’s test p < 0.001). Two principal components explained 70.9 % of the variance. The Cronbach’s ɑ for all constructs exceeded 0.850, with an overall reliability of 0.907. CFA was subsequently performed using Mplus 7.4 on 334 responses, which further validated the model.

ACAP was measured using Limaj and Bernroider's (2019) scale. PACAP (seven items) assesses the supplier's ability to acquire and assimilate external knowledge, while RACAP (six items) measures its capability to integrate and apply knowledge for innovation. For customer orientation, seven items based on Atuahene-Gima (2005) were used to assess the extent to which suppliers acquire, disseminate, and utilize customer information. Digital trust was measured with three adapted items from Chen et al. (2025).

Control variables include firm size and supplier-buyer collaboration duration. Larger firms typically invest more resources in learning, while longer collaboration enhances knowledge integration and innovation contributions through stable relationships and technological synergy.

Analytical approachMeasurement model validationTo ensure the measurement model’s reliability and validity, a two-step analytical procedure comprising EFA and CFA was employed. First, EFA was conducted using SPSS 27.0 to explore the factor structure of the measurement items. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value exceeded 0.9, indicating excellent sampling adequacy. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), confirming that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Items with factor loadings below 0.60 were removed to improve measurement quality.

Subsequently, CFA was performed using Mplus 7.4 to validate the factor structure and assess convergent validity. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices: the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The model demonstrated a good fit based on commonly accepted thresholds (e.g., χ²/df < 3, CFI/TLI > 0.90, and RMSEA < 0.08). Convergent validity and internal consistency were confirmed by standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR). Discriminant validity was supported by verifying that the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs.

Regression and moderation testingTo test the proposed hypotheses, HRA was conducted using STATA 18.0. This method is suitable for assessing the incremental effects of predictors and interaction terms. All continuous variables were mean-centered before constructing interaction terms to reduce multicollinearity. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values were calculated and reported to assess multicollinearity.

The analysis proceeded in three stages:

Step 1: Control variables were introduced. Firm size and relationship duration were included to control for their potential effects on supplier innovation (SI).

Step 2: Independent variables were added. Operations transparency (OT) and strategy transparency (ST) were entered to examine their direct effects on supplier innovation (H1a and H1b).

Step 3: Moderating variables and interaction terms were introduced. Four moderators—PACAP, RACAP, supplier’s customer orientation (SCO), and digital trust (DT)—were sequentially included, along with their interaction terms with OT and ST, to test the moderating effects (H2a–H5b).

Given that all variables were measured using self-reported data collected from the same respondents via a cross-sectional survey, the potential for common method bias (CMB) exists (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To mitigate this risk, both procedural and statistical remedies were implemented following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003).

Procedurally, respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality to reduce evaluation apprehension and social desirability bias. Furthermore, the questionnaire was designed to randomize the order of items and interleave questions across different constructs, thereby introducing psychological separation and reducing the likelihood of response pattern bias.

Harman’s single-factor test was conducted as an initial diagnostic for CMB. An unrotated principal component analysis of all measurement items revealed seven factors with eigenvalues greater than one, with the first factor accounting for 39.96 % of the total variance, well below the 50 % threshold. Thus, no single factor dominates the variance, indicating a limited risk of CMB.

EFA/CFA analysis and validityTo assess the measurement model’s structural validity and reliability, we conducted an EFA followed by a CFA.

The EFA, performed using SPSS 27.0, yielded a KMO value of 0.940 and a significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ² = 15,710.508, p < 0.001), indicating that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. All item factor loadings in the EFA exceeded 0.60, supporting convergent validity within constructs.

Subsequently, CFA was conducted using Mplus 7.4 to further validate the measurement model. The model demonstrated a good fit to the data, with χ²/df = 2.566, TLI = 0.918, CFI = 0.924, and RMSEA = 0.068. All standardized factor loadings were statistically significant and exceeded 0.70, indicating strong indicator reliability.

Convergent validity and internal consistency were further supported by Cronbach’s ɑ, CR, and AVE. As shown in Table 3, all Cronbach's ɑ and CR values exceeded 0.70, while all AVE values exceeded 0.50. Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion: the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs.

Data reliability and validity results.

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the key variables. All correlations were in the expected direction and consistent with theoretical predictions, further supporting the measurement model’s construct validity.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Notes: Diagonal elements are the square root of the AVE. ⁎p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05, and ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.01.

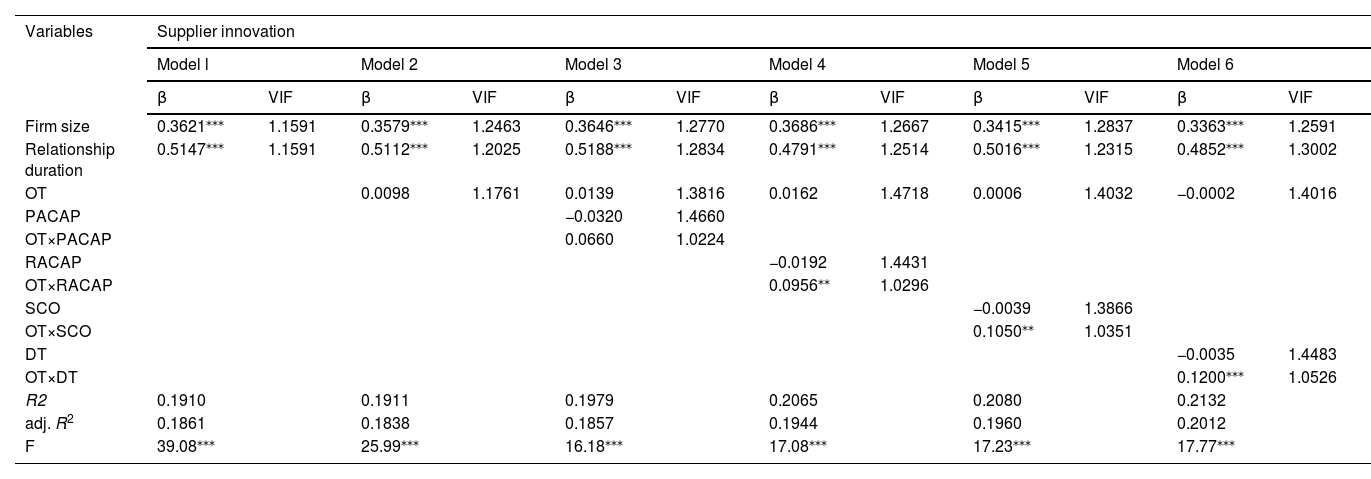

To address potential multicollinearity, all continuous variables were mean-centered before constructing interaction terms. The results of hypotheses testing, shown in Tables 5 and 6, indicate that all VIF values are below 2, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a significant concern.

Regression results I.

Note:⁎p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05, and ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.01.

Regression results II.

Note:⁎p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05, and ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.01.

First, Model 1 includes only the control variables (firm size and relationship duration), which show significant positive effects on supplier innovation. Second, Models 2 and 7 introduce OT and ST, respectively. Neither shows a significant effect, indicating that H1a and H1b are not supported. Thus, transparency alone does not automatically promote supplier innovation. Rather, its effectiveness may depend on supplier-specific characteristics, warranting further examination of boundary conditions. Finally, Models 3 through 11 incorporate the moderator variables (PACAP, RACAP, SCO, and DT) along with their interaction terms with OT and ST.

In Models 3 and 8, the interaction between PACAP and ST is significant (β = 0.092, p < 0.05), whereas the interaction with OT is not. This supports H2b but not H2a, suggesting that ST requires suppliers to have strong PACAP to effectively convert such information into innovation.

Models 4 and 9 show that RACAP significantly strengthens the positive effects of both OT and ST on innovation (β = 0.0956, p < 0.05; β = 0.1551, p < 0.01), supporting H3a and H3b. These results highlight the importance of knowledge transformation and application capabilities in fostering innovation.

Models 5 and 10 confirm the moderating role of SCO, with significant interaction terms for both OT and ST (β = 0.1050, p < 0.05; β = 0.1467, p < 0.01), supporting H4a and H4b. Thus, customer-oriented suppliers are better able to recognize and act on transparent information.

Models 6 and 11 demonstrate that DT significantly enhances the positive impact of transparency on innovation (β = 0.1200, p < 0.01; β = 0.1344, p < 0.01), supporting H5a and H5b. Thus, when suppliers trust the buyer's digital systems, they are more willing to utilize transparent information for joint innovation.

Table 7 summarizes the result of hypothesis testing, including standardized coefficients (β), significance levels (p-values), and explanatory power (R²). Fig. 2 presents a visual representation of the model, illustrating the significant paths and regression coefficients.

Summary of hypothesis testing results.

Notes: ns = not significant; ⁎p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05, and ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.01.

To further interpret and contextualize these findings, the following section discusses the results in the context of prior research and theoretical frameworks.

DiscussionDiscussion of resultsHere, we critically compare our findings with the literature and explore the underlying mechanisms.

First, the statistically insignificant direct effects of both operations and strategy transparencies on supplier innovation diverge from the findings of a prior study (DeCampos et al., 2022), which posited that transparency inherently enhances collaborative performance. However, the findings align with another study (Patrucco et al., 2024), which argued that information sharing does not directly foster supplier commitment. Rather, its value depends on whether the buyer holds a “preferred customer” status. Thus, the innovation-enhancing effects of transparency are not universally valid but are instead contingent on contextual factors and supplier characteristics.

The insignificant effect of OT may reflect the execution-oriented mindset of many Chinese manufacturing suppliers, particularly SMEs. These suppliers often interpret operational information as instructions or coordination tools rather than as a basis for innovation. In competitive, low-margin markets, they tend to focus on short-term efficiency rather than engaging in risky innovation. The limited digital infrastructure further hinders their ability to absorb and utilize operational data, reducing the value of transparency (Montecchi et al., 2021). Similarly, the ineffectiveness of ST may stem from the abstract nature of the information provided, which often lacks actionable guidance. When buyers share long-term visions without concrete support, suppliers may find it difficult to convert this information into R&D activities. Some suppliers may also intentionally downplay strategic signals to avoid revealing their plans within the collaboration network, a behavior known as strategic avoidance. This cautious response to unstructured information reveals a lack of effective alignment mechanisms between buyers and suppliers. Additionally, information overload may further impair suppliers' ability to identify and apply critical strategic insights (Eggert & Helm, 2003; Gardner et al., 2019).

These findings are also consistent with the “dark side of transparency” theory. Chen (2023) argued that information disclosure effectiveness depends on the recipient's ethical compliance and cognitive readiness. If suppliers lack the necessary capabilities, transparency may trigger adverse effects. Another study (Huang & Yang, 2016) on manufacturing outsourcing found that suppliers only benefit from information transparency under specific conditions.

Second, within the “ability” dimension of the MOA framework, ACAP shows structural differentiation. PACAP significantly moderates the effect of ST but not OT. This result aligns with the findings of Atkins et al. (2021). Strategic information is complex and loosely structured, requiring strong knowledge identification and assimilation capabilities. Conversely, OT involves standardized and routine-based information, such as orders and inventory, which can be handled even with weaker PACAP. The limited role of PACAP also reveals practical challenges: Although many Chinese suppliers have access to market and technological information, they are constrained by limited R&D capacity and resource bases, making it difficult to internalize knowledge and apply it to innovation. Thus, transparency alone cannot drive innovation without adequate internal capabilities (Sikombe & Phiri, 2019).

Conversely, RACAP significantly moderates the effects of both OT and ST. This supports Božič and Dimovski’s (2019) view that transforming and applying knowledge is critical to achieving innovation. Suppliers with high RACAP can effectively integrate transparent information into R&D, process improvements, and product upgrades, leading to higher-quality innovation (Ali et al., 2016).

Third, both variables under the “Motivation” dimension—supplier’s customer orientation and digital trust—demonstrate significant positive moderating effects. Consistent with Jean et al. (2017), customer orientation enhances the supplier’s willingness to identify buyer needs and respond to shared information, thereby facilitating proactive product and technological adjustments. Conversely, suppliers with low customer orientation may lack the intrinsic motivation to seize innovation opportunities enabled by buyer transparency.

Meanwhile, digital trust significantly improves suppliers’ acceptance of digital platforms and data-sharing mechanisms. This supports the findings of Mubarak and Petraite (2020) and Kluiters et al. (2023), which show that when suppliers perceive platforms as secure and data as reliable, they are more likely to rely on transparent information and engage in collaborative innovation. This is especially relevant in emerging economies, where digital transformation remains uneven. Digital trust can compensate for weak institutional trust or limited technological capabilities, serving as a key psychological enabler of data-driven collaboration.

Overall, transparency alone does not drive supplier innovation. Its impact depends on whether suppliers have the ability and motivation to absorb, interpret, and act on the information. This insight not only demonstrates the relevance of the MOA framework but also offers a comprehensive lens for understanding the complex dynamics of buyer-supplier innovation.

Theoretical contributionsFirst, this study reconceptualizes buyer transparency not merely as a governance tool for enhancing efficiency, but as a strategic driver of inter-organizational innovation. While studies have predominantly focused on transparency’s role in improving supply chain performance, sustainability, or risk control (Bai & Sarkis, 2020; Cousins et al., 2019; Morgan et al., 2023), its potential to stimulate supplier innovation has been underexplored. By developing a two-dimensional structure of operations and strategy transparencies, along with a supplier-oriented measurement scale, this study reveals how different transparency dimensions impact innovation. These insights support calls by Hultman and Axelsson (2007) and Mol (2015) for a more nuanced understanding of transparency. Moreover, in today's global supply chains marked by digitalization, complexity, and geopolitical uncertainty, the findings emphasize the strategic value of selective transparency. Disclosing sensitive strategic information without ensuring that suppliers possess adequate capabilities and motivation may be counterproductive, and even trigger opportunistic behaviors (Paulraj et al., 2025; Perotti et al., 2022). Therefore, transparency should be contextually aligned with suppliers’ capability and behavioral intentions, and managed dynamically.

Second, this study emphasize the proactive role of suppliers in the innovation process, thereby extending the traditionally buyer-centric perspective. Research has predominantly examined buyer-driven mechanisms (Constant et al., 2020; Perols et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2005; Schiele et al., 2011), often neglecting the behavioral foundations of how suppliers respond to and engage with buyer practices. Drawing on the MOA framework, this study argues that the opportunity provided by transparency can only be translated into innovation outcomes when suppliers possess sufficient “ability” (ACAP) and “motivation” (customer orientation and digital trust). This framework integrates perspectives from the resource-based view and dynamic capability theory, while also incorporating mechanisms related to behavioral intention and cognitive readiness to better explain inter-organizational innovation. Moreover, the study responds to Sikombe and Phiri's (2019) call for exploring multi-factor pathways in tacit knowledge transfer by highlighting the crucial roles of supplier integration, informal interaction, and relationship quality in transforming information into innovation.

Third, this study incorporates digital trust into the transparency-innovation pathway, addressing the growing interest in technological trust mechanisms within digital supply chains and enriching our theoretical understanding of trust in the digital era. Unlike traditional studies that emphasize inter-organizational or interpersonal trust, this study emphasizes system-based trust—suppliers’ confidence in digital platforms, data security, and information control—as a key driver of transparent information adoption (J. Chen et al., 2025; Mubarak et al., 2019). When suppliers trust buyers’ digital systems, they are more likely to absorb and apply knowledge derived from transparency (Kmieciak, 2021; Mubarak & Petraite, 2020). In emerging economies with weak institutional trust and uneven digital maturity, digital trust serves as a vital psychological compensatory mechanism. It improves the efficiency of information processing and strengthens collaborative innovation in digitalized supply chains.

Finally, this study extends the application of the MOA framework from individual behavior and intra-organizational management to inter-organizational innovation. Although MOA has been widely applied in marketing, organizational behavior, and management research, its use in supply chain innovation remains limited. By illustrating how motivation, opportunity, and ability jointly explain the interaction between buyer practices and supplier innovation, we demonstrate MOA’s potential to integrate resource-based views, relational governance, and behavioral mechanisms. It offers a unified behavioral lens for understanding the complexities of buyer-supplier relationships.

Managerial implicationsFirst, when suppliers have limited internal knowledge, external information becomes critical for innovation (Jean et al., 2017). Procurement managers should implement tailored and conditional transparency strategies, considering the maturity of the buyer-supplier relationship, the supplier’s ACAP, and motivational alignment. To prevent information overload, transparency should be tiered. For example, basic operational data should be shared with all suppliers while reserving strategic information for those with stronger innovation capabilities. Transparency should serve both as a monitoring tool and shared platform for innovation planning, especially within digitally integrated supply networks.

Second, strengthening suppliers’ ACAP is essential to fully leverage buyer transparency. Buyers should incorporate capability-building into their strategic sourcing by providing targeted training in digital tools, data analytics, and buyer-specific strategic knowledge (Algarni et al., 2023). Investments in knowledge management systems and AI-driven analytics can reinforce suppliers’ knowledge infrastructure. Experiential learning through cross-organizational initiatives, such as supplier academies, PACAP boot camps, and RACAP workshops, can help suppliers develop transformative capabilities. Inspired by Toyota’s “Obeya” model, embedding engineers within supplier firms can also promote joint knowledge creation.

Third, transparency initiatives are effective only when suppliers are willing to act on the information provided. Before implementing such initiatives, buyers should evaluate strategic alignment with suppliers, and cultivate stronger relational ties to enhance supplier autonomy and commitment (Hartley & Jones, 1997). This can be achieved through open communication, joint planning, and incorporating innovation contributions into performance assessments. For suppliers with lower customer orientation, buyers should clearly communicate strategic objectives, share market insights, and involve them in collaborative planning. Governance mechanisms should offer flexibility to suppliers in deciding their level of participation, thereby moving away from a one-size-fits-all model toward a more adaptive approach.

Finally, establishing digital trust is crucial for collaborative innovation in data-driven supply chains. In emerging markets, where social trust may be limited, technology-based trust mechanisms can provide effective support. Buyers should invest in robust digital infrastructure, such as blockchain, industrial IoT systems, and standardized communication protocols (Kluiters et al., 2023). Third-party compliance certifications and regular audits can further boost supplier confidence. Crucially, buyers must ensure bidirectional transparency—sharing information and involving suppliers in data governance—to promote perceived fairness and autonomy. Policymakers and platform providers should actively contribute to building digital trust and enhancing supplier capabilities, especially in culturally diverse or institutionally fragmented supply chains.

In conclusion, as Chinese manufacturing firms advance digital transformation, supply chain managers should focus on strengthening supplier capabilities, fostering customer orientation, and building digital trust to drive supplier innovation. Future research should explore how emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, big data, and IoT, can enhance transparency mechanisms and support long-term supply chain competitiveness.

ConclusionThis study introduces the MOA framework into supply chain management and open innovation to investigate the conditions under which buyer transparency effectively stimulates supplier innovation. Analyzing data from 334 Chinese manufacturing suppliers, we find that neither operations nor strategy transparency directly drives supplier innovation. Instead, their effectiveness depends on the supplier ACAP, customer orientation, and digital trust. Specifically, RACAP significantly moderates the effects of both types of transparency, while PACAP plays a significant role only for strategy transparency. Moreover, suppliers with stronger customer orientation or higher digital trust are more willing to leverage the disclosed information from buyers for innovation purposes.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the transparency literature by shifting the focus from governance and efficiency to innovation, and conceptualizing buyer transparency as a multidimensional construct. It also enriches the MOA framework and understanding of inter-organizational innovation by applying it to the buyer-supplier interface, highlighting suppliers’ autonomy in processing external information. By identifying the critical and contingent roles of supplier ACAP, customer orientation, and digital trust, this study extends prior relational and resource-based perspectives. Moreover, the inclusion of digital trust introduces a novel behavioral mechanism for understanding innovation in digitally mediated supply chains.

Practically, the findings suggest that transparency alone is insufficient to stimulate supplier innovation. Buyers must also consider their suppliers’ internal readiness. Investments in capability building, incentive alignment, and mechanisms for fostering digital trust are essential for collaborative innovation. These efforts are especially important in digitally transforming economies, where supplier innovation depends not only on access to information but also on the willingness and ability to act on it.

LimitationsFirst, the data were collected using a cross-sectional survey design, which restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. Innovation is inherently a dynamic process influenced by knowledge accumulation and environmental changes. Although the hypothesized relationships are grounded in theory, longitudinal or experimental designs can provide stronger evidence of causality. Second, all data were self-reported by supplier-side respondents. While procedural and statistical remedies (e.g., Harman’s single-factor test) were employed to mitigate CMB, the reliance on self-reported survey data still poses potential limitations. Third, this study exclusively focuses on Chinese manufacturing suppliers. Given China’s significant role in global supply chains, the context is practically and theoretically relevant. However, the generalizability of the findings to other institutional or cultural settings remains limited. Fourth, although firm size and relationship duration were controlled for, other contextual variables, such as industry type, technological intensity, or power asymmetry in buyer-supplier relationships, were not accounted for and may influence the effectiveness of buyer transparency. Finally, while this study investigates how supplier ability and motivation moderate the relationship between transparency and innovation, it does not explore the potential mediating mechanisms.

Future research directionsFirst, longitudinal studies can capture the evolving nature of buyer-supplier interactions and explore how motivation, opportunity, and ability develop over time under the influence of transparency and digital transformation. Second, complementary methods, such as qualitative case studies or multi-source datasets (e.g., matched buyer-supplier dyads or archival innovation indicators), can enhance the validity and richness of empirical insights. Third, future studies may test the MOA framework’s applicability in other industrial contexts (e.g., logistics, pharmaceuticals, high-tech, or service supply chains) and across different geographical regions (e.g., Europe, North America, or Southeast Asia). Such comparative research can help clarify contextual contingencies and enhance the generalizability of findings. Fourth, scholars are encouraged to extend the MOA framework by incorporating additional dimensions of motivation, opportunity, and ability (e.g., supplier strategic intent, buyer dependence, institutional support, or AI-enabled decision-making capability) to capture the more nuanced mechanisms of innovation in supply chains. Fifth, while we focus on the moderating effects of supplier characteristics, future research can examine whether motivation and ability mediate the relationship between buyer transparency and innovation. This can reveal the underlying knowledge transfer mechanisms, and offer deeper insights into how suppliers internalize and operationalize transparency. Finally, digital technologies are increasingly important in inter-organizational collaboration. As such, future research should refine the constructs of digital trust and ACAP in digital environments, and investigate how emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and digital twins interact with buyer transparency to shape innovation outcomes.

FundingThis research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 23BGL073).

CRediT authorship contribution statementSuicheng Li: Conceptualization. Wenjing Hou: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Xinyi Zhang: Methodology. Huifang Wu: Software.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.