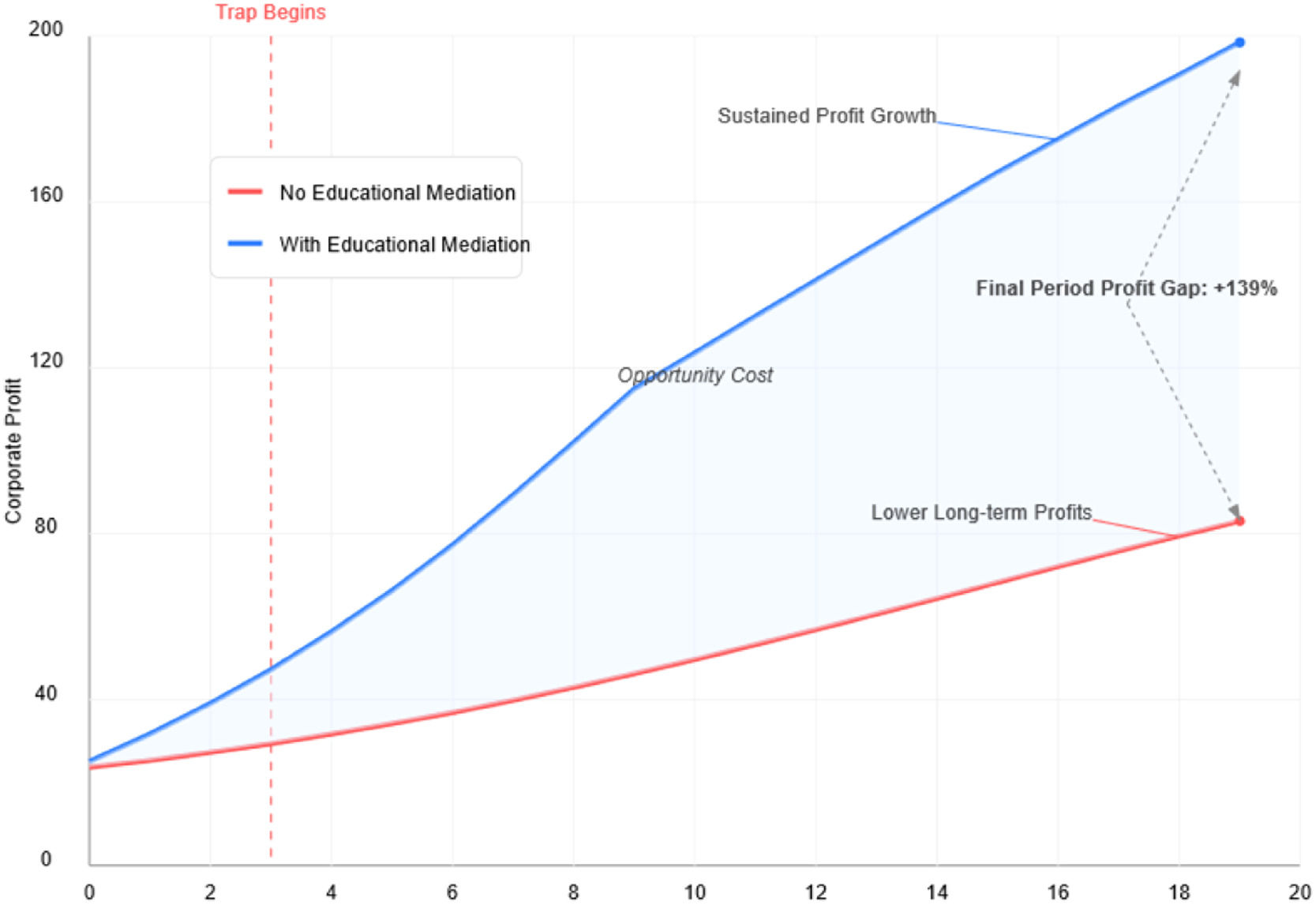

Artificial intelligence’s (AI) rapid growth in creative industries has created a difficult choice: While companies can use AI to work faster, this often reduces human creativity and innovation. We show how educational institutions can resolve this by bringing together different groups to work collaboratively rather than competing against each other. We use a mathematical model to study how four key groups interact: creative companies, government regulators, educational institutions, and creative professionals. Our model tracks these interactions over 20 time periods, measuring three important factors: creative resources, trust between groups, and technology advancement. We compare scenarios where education plays different roles, from being a passive follower to active coordinator. Surprisingly, we find that when educational institutions actively coordinate between the other groups, everyone simultaneously benefits. Our 20-period simulation reveals that compared to pursuing automation-only strategies, companies following education-mediated strategies achieved 139 % higher profits (scenario simulation ceiling). Instead of being a zero-sum game, all groups achieved better outcomes together. This is because that educational coordination preserves and enhances creative resources while enabling sustainable technology integration. Thus, education is not simply a cost that responds to technological change. Rather, it is a strategic tool that can transform competitive dynamics into collaborative innovation. Educational institutions provide the long-term perspective, neutrality, and knowledge integration needed to align different interests around sustainable AI-creativity partnerships. However, educational coordination faces profound limitations, including structural power asymmetries wherein multinational corporations possess superior resources compared to individual artists, cultural incompatibilities rendering Western frameworks inappropriate across diverse contexts, and funding challenges undermining institutional neutrality. Rather than providing universal solutions, we offer diagnostic tools for understanding when coordination mechanisms may be feasible. Meanwhile, we also acknowledge that many contexts require alternative approaches or may experience ongoing efficiency-creativity tension as an inevitable feature of contemporary creative industries.

The Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Creativity Paradox captures a persistent dilemma in contemporary creative industries: AI promises unprecedented production efficiencies while potentially undermining the creative capital that sustains long-term innovation (Artemov, 2024; Felicetti et al., 2024; Moravec et al., 2024; Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 1997). This tension manifests when firms optimise for immediate productivity gains at the expense of creative capacity, regulatory responses lag behind technological development, and creative professionals lose strategic direction amid accelerating change. We depart from technologically deterministic approaches by examining educational institutions as potential coordination mechanisms between competing stakeholder interests. This perspective identifies overlooked possibilities for institutional mediation while acknowledging significant uncertainties about implementation feasibility. Crucially, while educational coordination may be effective under specific conditions, substantial barriers (e.g., resource constraints, political pressures, and cultural misalignments) may prevent such arrangements from emerging in practice. Our proposed theoretical framework positions these questions as empirically testable propositions rather than predetermined outcomes, emphasising the conditional nature of institutional solutions to technological challenges.

Real-world evidence supports our modelling assumptions about educational mediation's critical role. Artists who leverage AI as creative partners (e.g., Mario Klingemann) demonstrate how educational preparation enables AI adoption to enhance, rather than deplete, creative output. This directly validates our creative capital evolution equation, wherein educational enhancement can offset automation depletion effects. Similarly, IBM Watson BEAT collaborations in music composition show that appropriate educational frameworks increase both creative complexity and participant motivation. This supports our model's trust evolution parameters and the prediction that educational mediation enables positive-sum rather than zero-sum dynamics.

Indeed, the unprecedented integration of generative AI technologies, such as Midjourney, DALL-E, and ChatGPT, are rapidly reshaping creative practices, democratising access to high-level design capabilities while simultaneously destabilising traditional creative roles. However, these technological affordances do not guarantee transformative outcomes. As empirical studies reveal, positive AI-creativity synergies typically emerge only under specific enabling conditions: Educational preparation that develops AI literacy alongside creative skills, collaborative frameworks that position AI as augmentation rather than replacement, and institutional mediation that manages stakeholder expectations.

However, we must acknowledge that AI-creativity relationships are deeply embedded within cultural contexts, which shape both creative expression and institutional coordination mechanisms. The cross-cultural variations in AI adoption, creative values, and educational institutional roles suggest that effective mediation strategies cannot be universally applied without careful adaptation to local contexts. Recent empirical evidence reveals striking geographic disparities in AI framing and acceptance: While the Global North media emphasises economic risks and efficiency concerns, Global South perspectives highlight potential societal benefits and democratisation opportunities (Ittefaq et al., 2025). These divergent cultural narratives reflect the fundamentally different relationships between technology, creativity, and institutional authority that our theoretical framework must accommodate.

We address this cultural complexity by developing an adaptive implementation framework that recognises educational mediation as conditionally rather than universally effective. Institutional coordination’s success critically depends on cultural compatibility factors, including authority structures, collaborative traditions, and temporal orientations, which vary significantly across societies. Rather than assuming uniform stakeholder behaviour, we model how cultural contexts influence trust formation, institutional legitimacy, and coordination mechanisms. This provides a more nuanced understanding of when and how educational institutions can effectively mediate AI-creativity tensions across diverse global settings. Our theoretical framework demonstrates that even seemingly ‘natural’ AI-creativity partnerships fundamentally depend on the educational and institutional mediating factors examined here. By endogenising educational strategy as a dynamic variable capable of altering system-wide equilibria, we provide a new lens for understanding how institutional arrangements can transform competitive dynamics into collaborative innovation, resolving the AI-Creativity Paradox through strategic coordination rather than accepting the inevitable trade-offs.

AI-creativity integration can yield positive outcomes in specific domains, such as generative art collaborations, where artists like Mario Klingemann leverage AI as creative partners, or music composition environments, where IBM Watson BEAT enables enhanced creative complexity. However, these successful cases actually reinforce our paradox framework. Positive AI-creativity synergies typically emerge under specific enabling conditions: educational preparation developing AI literacy alongside creative skills, collaborative frameworks positioning AI as augmentation rather than replacement, and institutional mediation managing stakeholder expectations. Without proper educational scaffolding and institutional support, the default trajectory tends toward the efficiency-creativity trade-offs we analyse. This strengthens our central thesis that even seemingly ‘natural’ AI-creativity partnerships fundamentally depend on the educational and institutional mediating factors our model examines.

Crucially, the unprecedented integration of generative AI into creative industries is catalysing systemic transformations across production workflows, skill architectures, and normative frameworks. Technologies such as Midjourney, DALL-E, and ChatGPT are rapidly reshaping creative practices, democratising access to high-level design capabilities while simultaneously destabilising traditional creative roles (Felicetti et al., 2024; Moravec et al., 2024). Vartiainen et al. (2023) empirically demonstrate such democratisation within middle school classrooms; here, students used AI to co-construct original digital artifacts, thus highlighting emergent, collaborative creativity. In fashion design, Lee and Suh (2024) employ the TPACK framework, showing that AI-enhanced ideation processes significantly increased students' design efficiency and satisfaction, albeit with technological dependency concerns. Hwang and Wu (2025) reveal that cultivating ‘AI visual literacy’, particularly prompt engineering and digital synthesis, is becoming central to graphic design pedagogy. These cases reflect a broader paradigmatic shift in creative education demanding reinterpretation through educational theory and institutional innovation.

Beyond design education, similar tensions surface in media and entertainment sectors (Cui et al., 2022). Broinowski and Martin (2024) argue that AI applications, such as deepfakes, generate new visual storytelling possibilities while challenging the epistemological foundations of public trust. This imbalance is exacerbated by limitations of purely science, technology, engineering, and mathematics-based regulatory frameworks. Through cross-national content analysis of 38,787 news articles, Ittefaq et al. (2025) identify geographic discrepancies in AI framing, with the Global North media emphasising economic risks and the Global South accentuating potential societal benefits. These discursive asymmetries suggest that AI integration cannot be universally theorised. Rather, educational and cultural institutions must tailor responses to context-specific priorities, particularly in developing countries, where Mannuru et al. (2023) highlight structural deficits in AI access and infrastructure.

AI-generated content is also challenging long-standing intellectual property regimes, as Shrayberg and Volkova (2025) have observed, calling into question the very notion of human authorship. These disruptions necessitate not only policy reform but also renewed institutional reflexivity across education and library acquisition practices. Liu and Liao (2025) provide compelling evidence of productive co-creation: In music composition, students collaborating with IBM Watson BEAT produced more complex works and demonstrated increased motivation, revealed by statistically significant shifts in complexity indices.

Nevertheless, technological affordances do not guarantee transformative pedagogy. As Creely and Blannin (2025)) illustrate using post-humanist frameworks, despite AI's presence, students often retain surface-level engagement strategies. Their autoethnographic experiments reveal emergent, yet unrealised, potential for deeper AI-human creative integration. Similarly, using multinational interviews, Gangoda et al. (2023) report that employers increasingly prioritise digital creativity and intellectual adaptability; these traits are not merely cultivated by technological exposure but by thoughtfully structured learning environments. These findings underscore the urgent need for education-centred equilibrium design within AI ecosystems (Huang, 2024).

The ethical dimension cannot be overlooked. Sampson and dos Santos (2023) model how AI may accelerate workforce substitution in professional services. Meanwhile, Paksiutov (2024) warns that AI-enabled cultural industries, if left unregulated, may reinforce dominant narratives at the expense of Global South identities. These challenges crystallise in what Vallis (2025) terms the ‘creative paradox’. This represents a systemic tension between efficiency-driven optimisation and preservation of subjective, humanistic creative agency. Wang and Liu (2023) argue that this paradox is not antagonistic but dialectical, necessitating institutional frameworks capable of maintaining dynamic equilibrium rather than enforcing binary resolutions.

Educational institutions face significant practical constraints which limit their capacity to serve as effective equilibrium mediators. This is particularly true in resource-constrained environments, where structural deficits in AI access and infrastructure create implementation barriers (Mannuru et al., 2023). Institutional rigidities, including bureaucratic inertia, traditional curriculum structures, and quality assurance systems, emphasising compliance over innovation may prevent institutions from achieving optimal engagement levels (Condette, 2024). Moreover, faculty development requirements, technology infrastructure investments, and industry partnership coordination demand substantial resources. Many institutions cannot sustainably provision these resources without external support. However, these limitations make strategic educational investment more, rather than less, critical for sustainable AI-creativity integration, as the absence of educational mediation increases the likelihood of falling into the efficiency traps and regulatory paradoxes our analysis identifies.

Traditional management theories struggle to accommodate this complexity. Xu and Chen (2023) reveal how surveillance-based classroom technologies may suppress student autonomy and inadvertently trigger ‘resistance creativity’. In higher education, Condette (2024) critiques quality assurance systems emphasising compliance over curricular innovation. Meanwhile, Rahman (2024) highlights the decentralised innovation in Indonesian healthcare as a viable alternative to rigid central planning. These examples demonstrate that control-based management systems often exacerbate rather than resolve the tensions inherent in creative governance under AI.

In response, game-theoretic models emerge as promising analytical tools to conceptualise these multi-stakeholder dynamics. Marshall et al. (2024) and Kindenberg (2025) demonstrate how constraint-based environments in sports and AI-mediated storytelling generate adaptive equilibria balancing creativity and structure. Gatti et al. (2023), Lasley (2024), and Kazmierczak et al. (2024) extend these insights to educational game design, revealing how layered equilibria (tactical, narrative, and social) enable participants to negotiate trade-offs and maintain systemic stability. These models reveal a critical insight: When educational institutions actively mediate AI-creativity tensions, dynamic and sustainable equilibria become achievable. Astashova et al. (2023) provide a formal framework rooted in motivational game theory. The authors demonstrate how, when carefully calibrated, educational equilibria between intrinsic creativity and extrinsic compliance yield optimal engagement. However, Alves et al. (2024) warn that biased algorithmic design can entrench ‘sticky equilibria’, reinforcing stereotypes and undermining equitable learning outcomes. Thus, AI integration in education demands continuously evaluating the equilibrium and a pedagogy of critical reflection.

Our game-theoretic framework applies most directly to contexts experiencing rapid technological change without corresponding institutional adaptation, Meanwhile, it also acknowledges that the AI-creativity paradox may be less pronounced in established creative-technology partnerships or well-resourced institutional environments. The model's predictive power is strongest where stakeholders lack coordination mechanisms, information asymmetries persist between technological and creative domains, and short-term efficiency pressures dominate long-term strategic planning. Importantly, even positive-case studies of successful AI-creativity integration typically reveal educational or institutional mediating factors (e.g., formal programs, collaborative learning environments, or adaptive governance structures) that align with our theoretical predictions about the necessity of strategic coordination for optimal outcomes.

Recent pedagogical research demonstrates that domain-general, top-down learning strategies better prepare students for adaptive creativity under AI contexts than narrow, skills-specific methods (Su et al., 2024; Choi et al., 2023). Institutional scaffolds also crucially shape entrepreneurial and critical capacities, as noted by Balasubramanian et al. (2023). Thus, educational institutions are not peripheral actors but equilibrium agents, capable of reconfiguring systemic tensions between innovation and control, standardisation and subjectivity, and efficiency and creativity.

Our theoretical framework positions educational mediation as a conditional rather than universal solution, with effectiveness contingent upon sufficient institutional capacity, stakeholder readiness, and supportive policy environments. Implementation success requires minimum thresholds, including faculty expertise in both creative and technical domains, baseline trust levels among stakeholders, adequate technological infrastructure, and regulatory frameworks permitting educational institutional autonomy. This conditional approach ensures that our theoretical contributions provide practical guidance for contexts where educational mediation is feasible, while recognising that alternative strategies may be necessary where institutional constraints prove insurmountable.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. Section 2 develops our theoretical framework, establishing game theory as an analytical lens for multi-stakeholder creative industry dynamics and formalising education's role as equilibrium mediator. Section 3 presents our four-player dynamic game model, detailing the mathematical formulation of strategic interactions between corporations, governments, educational institutions, and creative professionals. Section 4 presents comprehensive simulation results, demonstrating the Corporate Efficiency Trap, Regulatory Timing Paradox, and education's unexpected role as a system equilibrator. Section 5 discusses the theoretical contributions, practical implications, and the paradigmatic shift from zero-sum to positive-sum thinking in AI-creativity integration. Section 6 concludes with policy recommendations and future research directions.

Theoretical frameworkGame theory provides a transformative analytical lens for reinterpreting strategic interactions within creative industries by shifting the focus from viewing creativity as an unpredictable artistic impulse to conceiving it as equilibrium outcome of multi-actor decision-making within evolving innovation systems. This approach facilitates the systemic understanding of how interdependent stakeholders, under varying constraints and incentives, jointly shape creative ecosystem trajectories. It builds upon previous evolutionary game theory applications modelling cooperation among creative enterprises that demonstrate competition, collaboration, and innovation diffusion within cultural sectors as structured behaviours, formally captured through game-theoretic frameworks, rather than random occurrences. The model introduces a four-player dynamic game structure involving key agents in an AI-augmented creative economy: creative corporations deploying AI tools prioritising profitability and innovation efficiency; government regulators establishing governance frameworks emphasising public welfare and risk mitigation; educational institutions cultivating talent, and shaping norms focusing on knowledge dissemination and long-term societal development; and independent creative professionals navigating technological transformation, seeking autonomy, expressive integrity, and sustainable livelihoods (Li et al., 2025).

A central theoretical innovation incorporates temporal dynamics and feedback structures into agents' utility functions, enabling the educationally-informed interpretation of long-run equilibria through conceptualising iterated, multi-period games where strategic payoffs evolve temporally as functions of previous decisions. Grounded in evolutionary game theory and repeated interactions, this approach allows agents to adjust behaviours based on empirical learning, strategic anticipation, and accumulated systemic consequences, thus moving beyond static optimisation logic. Crucially, two endogenous state variables are introduced: creative capital, representing collective innovation potential reservoir, and inter-agent trust, capturing confidence across institutional boundaries. Both evolve based on agents' cumulative decisions as active feedback mediators enabling the model to reflect pedagogically relevant dynamics, including learning curves, reputational path dependencies, and systemic saturation thresholds, rather than functioning as passive indicators.

Our theoretical framework positions educational mediation as a conditional, rather than universal solution. Its effectiveness is contingent upon sufficient institutional capacity, stakeholder readiness, and supportive policy environments. We hypothesise that educational institutions may function as effective mediators under specific enabling conditions, including faculty expertise in both creative and technical domains, baseline trust levels among stakeholders, adequate technological infrastructure, and regulatory frameworks permitting educational institutional autonomy. However, these conditions may prove elusive or entirely absent in many real-world contexts. Our conditional approach ensures that our theoretical contributions provide practical guidance for contexts where educational mediation is feasible while recognising that alternative strategies may be necessary where institutional constraints prove insurmountable. The gap between mathematical elegance and empirical complexity calls for intellectual humility about what game-theoretic modelling can accomplish in domains where cultural meaning, aesthetic value, and human creativity remain fundamentally resistant to quantification.

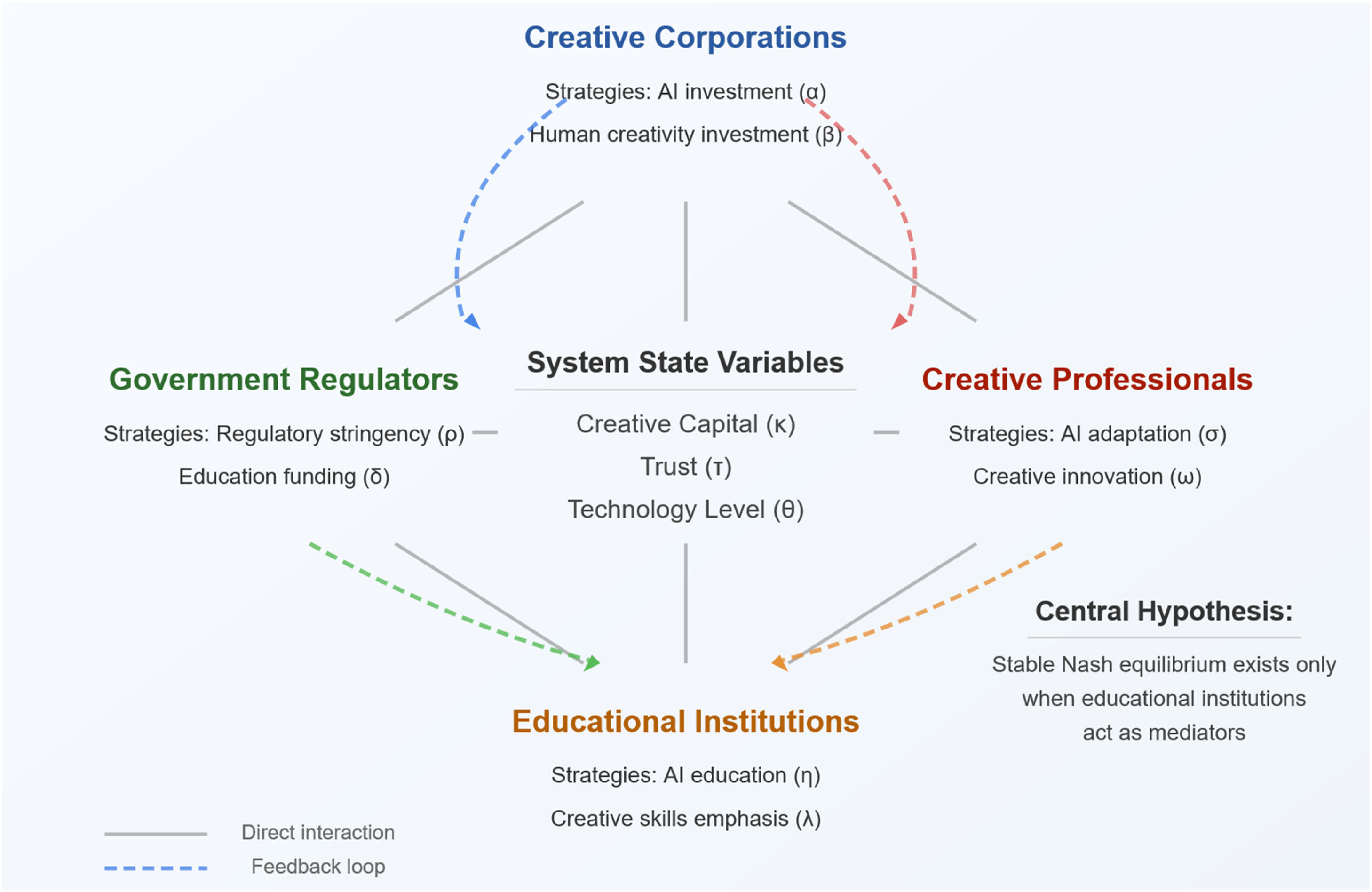

Our formal multi-agent game model includes four players: Creative corporations (C), Government regulators (G), Educational institutions (E), and Independent creative professionals (P). They make strategic decisions over multiple time periods t = 1, 2, …, T. The system state at time t is represented by Creative Capital (κt), Trust (τt), and Technology Level (θt). Each agent controls strategic variables: Corporations manage AI investment (αt), human creativity investment (βt), and collaboration with educational institutions (γt). Governments control regulatory stringency (ρt), education funding (δt), and creative sector support (φt). Educational institutions determine AI education emphasis (ηt), creative skills emphasis (λt), and industry partnership level (μt). Professionals decide on AI adaptation level (σt), creative innovation level (ωt), and educational engagement (ξt). Fig. 1 captures the model’s core elements, showing how each stakeholder makes strategic decisions that influence the system state variables over time. The dynamic feedback loops represent how strategies and payoffs evolve based on past outcomes, creating an iterative game where today's actions affect tomorrow's payoffs.

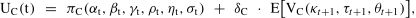

The utility functions for each agent incorporate both immediate payoffs and future impacts through state variables, such as corporate utility:

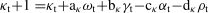

where πC represents immediate profit, VC represents future value based on state variables, and δC is a discount factor. Similar utility functions apply for other agents, reflecting their respective objectives.The state variables evolve according to transition equations: Creative capital evolution follows:

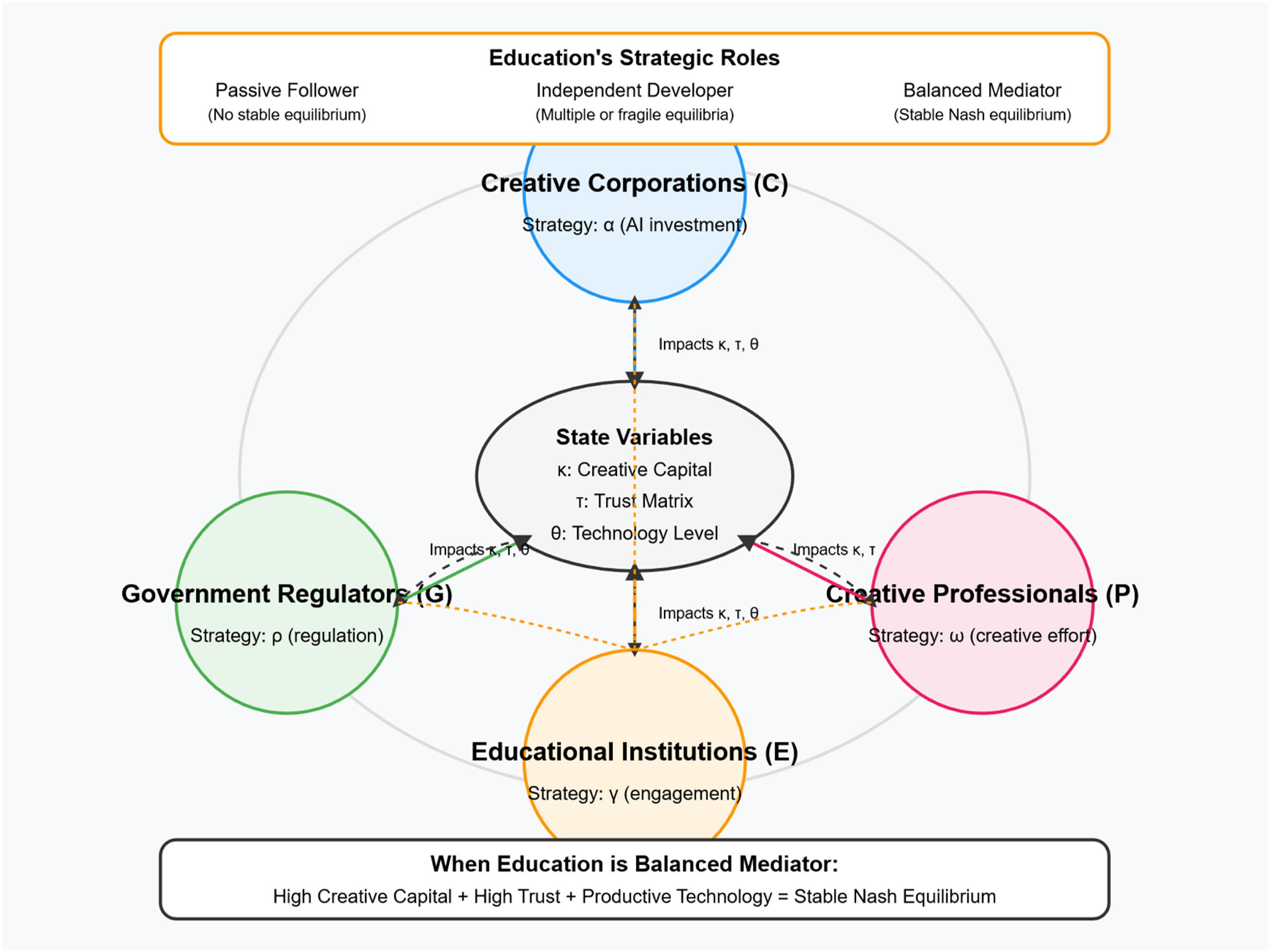

where g1 represents growth from creative investments and d₁ represents potential decline from excessive automation. Trust evolution occurs through τt+1(i,j) = f2(τt(i,j),actions) for all agent pairs (i,j), while technology evolution follows θt+1 = f3(θt,αt,ηt,σt,ρt). For equilibrium analysis, a strategy profile S* = (SC, SG, SE, SP) is a Nash equilibrium if for each agent i and any alternative strategy Si′, Ui(Si,S−i) ≥ Ui(Si′,S−i*). To test our central hypothesis, we examine scenarios where education takes different roles: passively following industry, prioritising creativity independent of market demands, or acting as a mediator with balanced priorities and feedback from all agents. The model predicts that only when education acts as a mediator will a stable equilibrium emerge that satisfies all players. This is a steady state where companies achieve sustainable AI integration preserving creative quality, governments enforce informed standards, and creatives adapt through lifelong learning. This model captures key dynamics described in the literature. These include the tension between profit-maximising automation and creative capital, transformative educational approaches balancing AI literacy with creative skills, global disparities in technology access, and game-theoretic constraints in educational settings. This provides a framework for resolving the AI-creativity paradox that pits efficiency against originality.Paradox mediation framework of AI in creative industriesModel formulationWe introduce a novel four-player non-cooperative dynamic game model to analyse the strategic interactions between key stakeholders in AI-driven creative industries. Our framework’s central innovation is incorporating temporal dynamics and feedback loops into agents' utility functions, enabling us to capture how decision-making and outcomes evolve over time (see Fig. 2).

Our modelling approach confronts a fundamental epistemological challenge: Creative industries operate through aesthetic judgment, professional identity concerns, and cultural meaning-making processes that resist mathematical optimisation frameworks. Rather than treating these as ‘bounded rationality’ deviations from an assumed norm, we acknowledge that creative decision-making follows entirely different logics that our game-theoretic approach can only approximate through heuristic simplification. The behavioural evidence reveals systematic patterns that fundamentally challenge our coordination assumptions. Creative professionals often reject AI integration based on professional identity and artistic values rather than utility calculations. We term these as ‘creative capital confusion’, where rational economic arguments systematically fail to overcome deeper psychological and cultural resistance. This represents not bounded rationality but alternative rationality systems that operate according to aesthetic, cultural, and expressive logics which game theory cannot adequately capture.

This behavioural realism enhances our model's explanatory power by accounting for persistent suboptimal strategies despite available information demonstrating superior alternatives. The Corporate Efficiency Trap emerges not merely from information asymmetries but from cognitive biases that systematically favour familiar technological solutions over uncertain collaborative arrangements. Our framework incorporates prospect theory insights revealing that stakeholders exhibit loss aversion and reference point dependence that fundamentally alter strategic calculations. Meanwhile, framing effects influence how coordination opportunities appear relative to institutional missions and stakeholder expectations.

The creative industry ecosystem is modelled with player set N={C,G,E,P} representing Creative Corporations (C), Government Regulators (G), Educational Institutions (E), and Creative Professionals (P). Time is divided into discrete periods t = 0, 1, 2, …, T with T potentially infinite for long-run analysis. In each period, each player chooses an action that influences immediate outcomes and the evolution of the system's state.

The strategic variables controlled by each player represent their primary decision levers. Creative corporations determine αt∈[0,1], the level of investment in or reliance on AI technologies, where higher values represent greater automation of creative processes. Government regulators set ρt∈[0,1], representing the stringency of regulation imposed on AI and creative practices, with higher values indicating stricter oversight. Educational institutions control γt∈[0,1], representing their degree of proactive engagement in integrating AI with creativity, and mediating between industry and workforce needs. Creative professionals decide on ωt∈[0,1], their level of creative innovation effort, reflecting investment in creative exploration and content creation.

The strategy profile at time t is denoted as a(t)=(αt,ρt,γt,ωt). A complete strategy for player i is a sequence si={ai(0),ai(1),…} that may depend on history or the current state. We focus on Markovian strategies that only depend on the current state variables.

The game's outcome in each period and available strategies in future periods are influenced by the system’s state. We introduce three key state variables that evolve over time through the interactions of the players' actions:

Creative Capital measures the aggregate creative resources and innovative capacity in the ecosystem. This intangible capital stock represents factors such as the pool of creative skills, diversity of creative ideas, cultural knowledge, and intellectual property accumulated in the industry. Its evolution follows:

Where gκ represents growth from educational initiatives and creative efforts, while dκ represents potential decline from excessive automation or restrictive regulation. For analytical tractability, we implement a linear form of the same:

The parameters aκ, bκ, cκ, and dκ > 0 calibrate the relative impacts. This formulation captures the ‘creative paradox’: Corporations that single-mindedly maximise efficiency through AI (high αt) without nurturing human creativity risk diminishing their creative capital over time.

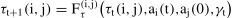

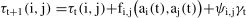

The Trust Matrix represents pairwise trust levels between each pair of stakeholder groups i and j at time t. Trust is crucial because cooperation and knowledge sharing hinge on each party’s confidence in the others' intentions. For example, τt(C,P) denotes the trust between Creative Corporations and Creative Professionals. High trust may signify that companies value creative workers, while low trust indicates tension. Education's role is particularly influential in building trust, as it can mediate and improve trust across the board. Trust evolves according to the following function:

A simplified linear form is:

Where ϕi,j measures how actions of i and j affect their mutual trust, and ψi,j captures education's mediating effect on trust between parties. If both players choose actions that are perceived as cooperative, trust increases. If their actions create conflict, trust decreases. The Trust Matrix is a pivotal state variable capturing social capital and goodwill in the game, influencing the ease of collaboration and formation of consensus-building equilibria.

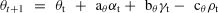

The Technology Level represents the technological advancement and integration of AI in the creative industry. This captures the cumulative effect of AI innovation and adoption in creative processes, such as the sophistication of generative AI tools and degree of automation in creative workflows. Its evolution follows:

A linear implementation is:

The parameters aθ, bθ, and cθ > 0 balance the contributions of corporate investment, educational diffusion, and regulatory constraints. This equation embodies the ‘regulatory timing paradox’: Government policy ρt often reacts to technology after it advances, creating a consistent lag where regulation is always chasing technological progress.

Thus, the system state at time t is st = (κt, τt, θt), encapsulating the creative capital, trust matrix, and technology level. The initial states0 = (κ0, τ0, θ0) is determined by the history up to the start of analysis. At each period, players choose actions a(t), which produce immediate payoffs and then update the state to st+1 via the transition functions described above.

Payoff functionsEach player aims to maximise their total expected utility over the game’s entire time horizon. We first define the instantaneous payoff that each player receives in period t from the current actions and state.

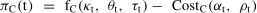

Creative corporations are primarily profit-driven. Hence, their payoff function is:

With a concrete specification:

This captures revenue from creative output (λ1κtθt), which requires both creative capital and technology, benefits from trust with other stakeholders (λ2∑j≠Cτt(C,j))), AI investment costs (λ32αt2) with diminishing returns, and regulatory compliance costs (λ4ρt). Without considering future effects, corporations may choose high αt and lobby for low ρt. However, doing so without considering creative capital can undermine future profit, resulting in the ‘Corporate Efficiency Trap’.

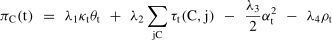

Government regulators aim to maximise social welfare and policy objectives:

Specifically:

Where τ¯trepresents average trust across all stakeholder pairs. This formulation includes welfare from creative capital (η1κt), technological advancement benefits (η2θt), social harmony from trust (η3τ¯t), and regulatory implementation costs (η42ρt2) with diminishing returns. The regulator's dilemma is to choose ρt that maximises social welfare while anticipating the effects on future creative capital and technology.

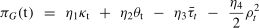

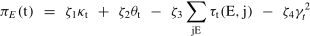

Educational institutions derive utility from knowledge and skill production:

With the form:

This represents benefits from creative development (ζ1κt), technological advancement (ζ2θt), stakeholder partnerships (ζ3∑j≠Eτt(E,j)), and costs of educational initiatives (ζ4γt2). Education's strategic decision γt balances the benefit of greater engagement against the immediate cost in effort and resources.

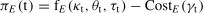

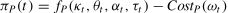

Creative professionals derive utility from economic rewards and creative fulfilment:

This can be expressed as:

This captures the benefits from the creative environment (ξ1κt), technology benefits moderated by corporate AI adoption (ξ2θt(1−αt)), value of trust with corporations (ξ3τt(P,C)), and creative effort costs (ξ42ωt2). θt(1−αt) suggests that AI technology improves professionals' output only to the extent to which corporations have not fully automated creative processes.

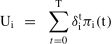

Each player’s ultimate objective is to maximise their total expected utility over the entire time horizon. We incorporate a discount factor 0 < δi < 1 for each player i, representing how much they value future payoffs relative to immediate ones. The total discounted utility for player i is:

With T→∞ for an infinite-horizon game. This summation reflects that a payoff earned t periods later is worth δit times what it would be worth if earned immediately.

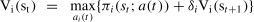

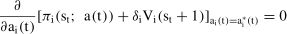

Equivalently, we define a value function Vi(st) for each player that gives the continuation value starting from state st at time t. The Bellman equation for player i at state st is:

Where st+1 follows from st and the actions via the state transition functions. Each player, when choosing their action ai(t), anticipates not only immediate payoffs but also the impact on future states, and thus, Vi(st+1). This intertemporal optimisation is at the heart of our dynamic game model.

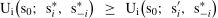

Equilibrium analysisWe seek a Nash equilibrium in the dynamic game. A Nash equilibrium is a set of strategies such that no player can gain by unilaterally deviating from their strategy, given the others are following the equilibrium strategies. Let σ={sC,sG,sE,sP} denote a strategy profile. A Nash Equilibrium strategy profile σ*={sC*,sG*,sE*,sP*} satisfies the following condition:

For all players i∈N and all alternative strategies si′. The first-order conditions characterising each player's optimal strategy are:

Solving these conditions simultaneously with the state transition equations yields the equilibrium trajectory (s0, a(0); s1, a(1); …). We are particularly interested in the steady-state properties of this equilibrium. A dynamic equilibrium is stable if the state variables converge to some long-run values (κ*, τ*, θ*) as t→∞ when players play σ*.

Educational institutions exhibit three distinct strategic roles with dramatically different system-wide consequences for AI-creative ecosystem stability. The Passive Follower mode represents reactive and conservative behaviour where institutions set γt*≈0. Essentially, they follow the industry and government leads with a lag by maintaining traditional curricula and slowly adapting after industry changes without actively intervening in AI-creativity integration. This effectively creates games without mediators that lead to suboptimal outcomes or unstable equilibria where corporations and professionals remain locked in efficiency versus employment conflicts while the government is perpetually catching up. This creates ongoing oscillations or creative capital declines without restoring forces. The Independent Development scenario involves institutions actively pursuing innovations without coordinating with corporations or professionals. Here, γ^t is moderate or high. However, education's strategy is driven by independent goals rather than explicitly mediating industry needs and creative workforce development through this ‘ivory tower’. This approach improves creative capital and technology generally but perhaps not in directions harmonising the system. This may lead to multiple equilibrium points or fragile equilibria where all players optimise without necessarily converging to shared expectations.

As a Balanced Mediator, education assumes active mediating roles where γ^t* is chosen to optimally to balance corporate, government, and professional needs by effectively internalising externalities among the other three players by coordinating curricula with industry needs. Meanwhile, it should professionals with abilities to leverage AI that enhance rather than replace creativity. Meanwhile, policymakers should be advised on realistic regulations. Under this mediator regime, education's engagement increases creative capital, supports technological diffusion, and crucially, aligns creative capital and technology with each other to avoid extreme outcomes where corporations do not need maximum AI investment levels. This is because well-trained creative workforces using AI yield high productivity with moderate investment. Meanwhile, creative professionals who can see training and supportive AI adoption are encouraged to undertake high creative effort. Moreover, a government observing more self-regulating ecosystems can set moderate regulations which protects against abuses without choking innovation. Effectively, trust between all parties rises, reinforcing cooperation through positive-sum dynamic feedback loops where high trust and creative capital yield better products and more stable growth. This can further convince players to continue this path toward steady states where creative capital, trust, and technology are all high. Essentially, each player's best response maintains the levels which achieve stable Nash equilibria and small deviations by one player become self-correcting. Meanwhile, the absence of educational mediation allows such deviations to spiral out of control because no counterbalancing force addresses creative capital losses. This formally demonstrates that when educational institutions optimise engagement to mediate between technology and creativity, this enables stable Nash equilibria. Meanwhile, passive or solely self-directed education means that no or an unstable equilibrium is reached.

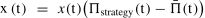

To further underscore the mediator equilibrium’s stability, we examine the situation through the lens of evolutionary game theory. We can analyse which strategy can replicate or spread over time by looking at the payoffs. In evolutionary terms, a strategy that yields higher payoff will tend to grow in prevalence. The replicator dynamics equation expresses this as follows:

Where x(t) is the proportion of the population playing a certain strategy at time t, Πstrategy(t)is the strategy’s payoff, and Π¯(t) is the average payoff in the population.

When we account for long-term system performance, the mediator strategy yields higher payoffs for all players, including educational institutions. Thus, an educational institution that adopts the mediator role can outperform one that remains passive or independent in terms of long-run outcomes. The replicator dynamic will favour the mediator strategy: Over time, more educational institutions would shift toward the mediator approach because it fits better in the ecosystem. The evolutionarily stable strategy in this ecosystem is one where all players gravitate toward the balanced approach facilitated by education as mediator.

Our four-player dynamic game model captures the intricate relationships between creative enterprises, government regulation, education, and creative professionals in the AI-driven creative economy. Using the Nash equilibrium concept, we find that the unique stable equilibrium emerges when the educational sector acts as a mediator, balancing efficiency and creativity across the system.

A stable Nash equilibrium with high creative capital, high trust, and productive technology exists if and only if educational institutions act as balanced mediators. This theoretical framework provides a novel quantitative lens to analyse and eventually resolve the AI-creativity paradox by elevating the role of education from a background player to a central orchestrator of equilibrium. The model demonstrates that when education mediates between technology and human creativity, all stakeholders can achieve sustainable, mutually reinforcing benefits rather than falling into efficiency-creativity trade-offs.

This methodological framework (see Appendix) represents a significant advancement in understanding AI-creativity dynamics. It provides, to our knowledge, the first rigorous game-theoretic formalisation of educational institutions as equilibrium mediators rather than passive respondents to technological change. Unlike extant studies that treat education as an exogenous input factor, our approach endogenises educational strategy as a dynamic variable capable of fundamentally altering system-wide equilibria. The comprehensive parameter specifications and sensitivity analysis establish empirical foundations that bridge theoretical innovation economics with practical policy implementation. Moreover, it offers policymakers and industry leaders with quantitative tools for strategic decision-making in AI-driven creative sectors.

The framework's methodological innovations extend beyond AI-creativity applications. It provides a generalisable template for analysing multi-stakeholder innovation systems where institutional mediation can transform zero-sum competitive dynamics into positive-sum collaborative outcomes. By demonstrating how educational engagement (γt) functions as a systemic equilibrator that resolves market failures, including information asymmetries, coordination problems, and temporal misalignment, this methodology establishes education as a strategic infrastructure rather than mere human capital development. The mathematical rigor, empirical grounding, and comprehensive sensitivity testing ensure that our findings provide reliable foundations for evidence-based policy and strategic planning in the rapidly evolving landscape of AI-augmented creative industries.

Parameter calibration and model limitationsOur parameter specifications transcend traditional literature-based calibration by systematically integrating detailed case study analysis that bridges theoretical modelling with observable real-world phenomena. Thus, we address the critical gap between abstract mathematical formulation and practical implementation contexts. The education-mediated trust enhancement parameters (ψi,j) derive not merely from Balasubramanian et al.’s (2023) institutional scaffolding research, but from the comprehensive analysis of documented collaboration cases where educational intervention demonstrably improved inter-stakeholder confidence across cultural and disciplinary boundaries. The creative capital evolution coefficients (ak, bk, ck, dk) are empirically grounded in Liu and Liao's (2025) meticulous documentation of music students collaborating with IBM Watson BEAT, where creative complexity indices rose from 3.56 to 4.79 while maintaining production efficiency. This provides concrete validation for our theoretical predictions about synergistic rather than competitive relationships between AI integration and creative enhancement.

Our utility function parameters reflect stakeholder-specific objectives and constraints while incorporating behavioural economics insights that fundamentally challenge pure rationality assumptions. Corporate parameters encompass revenue generation (λ1), trust benefits (λ2), AI investment costs (λ3), and regulatory compliance costs (λ4). However, these specifications now acknowledge the systematic short-termism bias (β = 0.85) reflecting quarterly performance pressures that override long-term optimisation, despite superior patient strategies. Government utility parameters (η1, η2, η3, and η4) balance social welfare considerations while incorporating political response cycles and anchoring bias, which create predictable regulatory lag patterns. Educational institution (ζ1, ζ2, ζ3, and ζ4) and creative professional parameters (ξ1, ξ2, ξ3, and ξ4) similarly integrate systematic deviations from perfect rationality through empirically-calibrated satisficing coefficients and identity preservation terms that capture artistic value priorities.

Robustness and sensitivity analysesTo verify the robustness of our core findings, we conduct comprehensive sensitivity analysis by systematically varying key parameters while incorporating creative industry behavioural realities constraints that better reflect actual stakeholder behaviour. Our enhanced framework demonstrates that educational mediation advantages persist and even strengthen when stakeholders exhibit realistic cognitive limitations including loss aversion, anchoring bias, and present bias toward short-term optimisation. We test the educational enhancement coefficient (bk) across ranges from 0.4 to 0.8 while simultaneously varying behavioural constraint parameters, revealing that coordination mechanisms functioning despite cognitive limitations prove more robust than those requiring perfect rational calculation.

The mathematical conditions for the Corporate Efficiency Trap gain enhanced explanatory power when behavioural factors are incorporated. Corporations persist in pursuing automation-focused strategies not merely due to information asymmetries, but because cognitive biases create systematic preferences for familiar technological solutions over uncertain collaborative arrangements. When automation depletion (ckαt) exceeds creative generation (akωt + bkγt), the trap emerges through behavioural mechanisms with availability heuristics, which make dramatic AI demonstrations more salient than gradual creative capital development benefits.

Discount factor analysis (δi∈[0.85,0.95]) reveals that patient development strategies maintain superior performance across varying stakeholder patience levels. Behavioural constraints actually amplify rather than diminish the advantages of educational mediation. Present bias and hyperbolic discounting make structured, institutionally-mediated coordination more rather than less valuable by providing commitment devices that help bounded rational actors overcome systematic short-term optimisation tendencies.

Systematic analysis of educational institutional capacity constraintsEducational institutions face formidable constraints that extend beyond resource limitations and encompass fundamental structural contradictions inherent in academic organisations. Resource constraints demand substantial investments in faculty development, technology infrastructure, industry partnerships, and curriculum redesign. For many institutions, these costs may exceed available budgets by 15–25 % of annual operating expenditures. These financial realities create the stark constraint condition γt ≤ γ¯ (Budgett), where achieving optimal engagement levels (γt ≥ 0.5) may require institutional investment levels that prove financially unsustainable without external support.

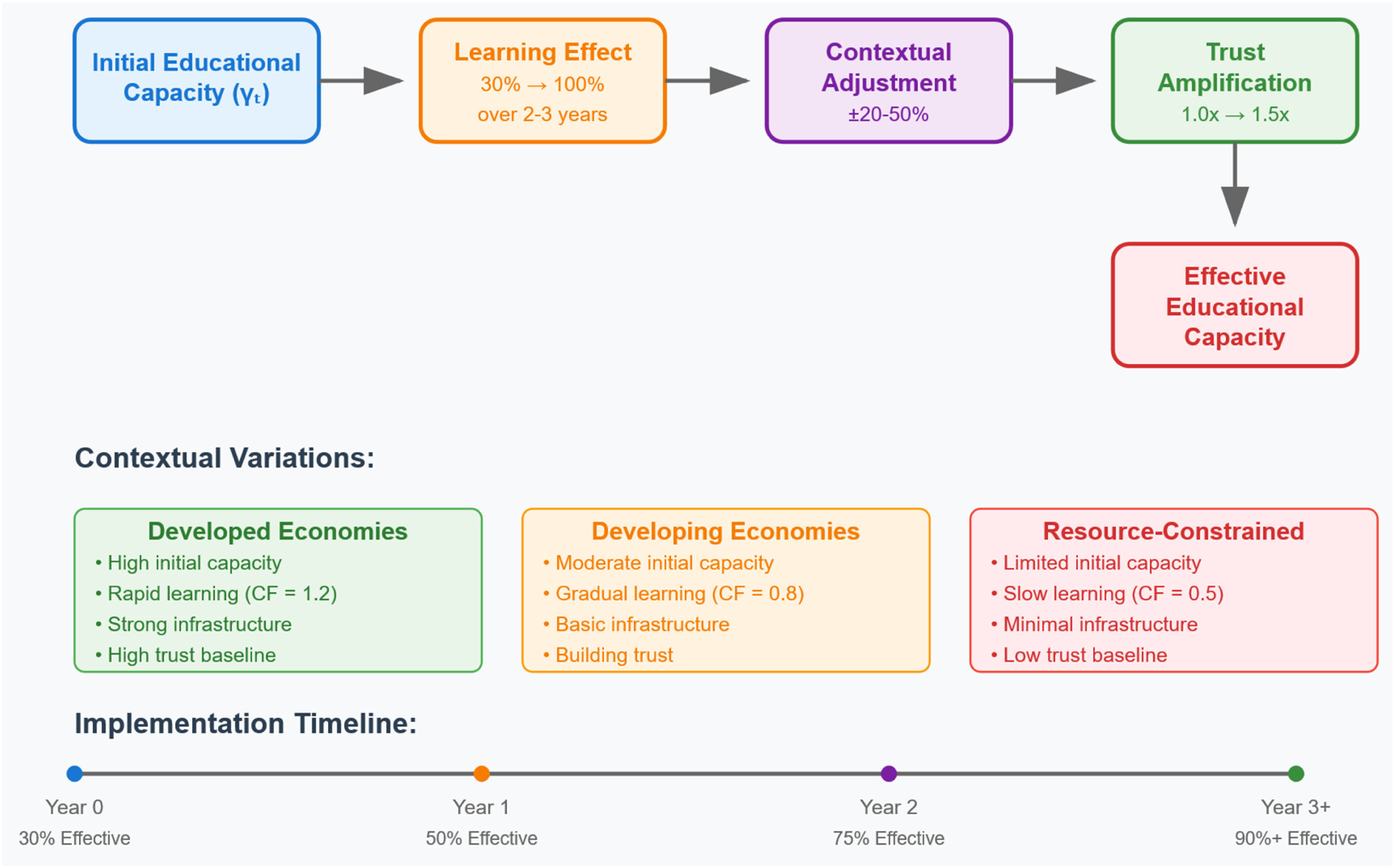

Institutional inertia presents even more intractable temporal challenges. Meaningful curriculum development demands sequential processes spanning faculty training and recruitment, administrative approval and accreditation, student cohort turnover, and institutional culture adaptation. However, these processes resist acceleration despite technological urgency. The impact of educational engagement (γt) on creative capital (κt+1) exhibits ineviTable 2–3 period lag effects. This creates implementation challenges where optimal strategies require sustained commitment over multiple institutional cycles rather than immediate optimisation responses.

Political and governance constraints impose additional limitations modelled as γt ∈ [γmin (political constraints), γmax (resource constraints)], where political minimum thresholds reflect policy mandates and regulatory requirements that may conflict with optimal coordination strategies. The quality assurance systems emphasising compliance over innovation that Condette (2024) critiques directly conflict with the adaptive, experimental approach required by our coordination model. Meanwhile, donor influence and corporate partnerships create conflicts of interest that systematically compromise the neutrality assumed by our framework.

Conditional implementation framework for contextual variationsWe propose a sophisticated cultural adaptation framework acknowledging that educational mediation effectiveness fundamentally depends on contextual factors beyond institutional capacity. These factors include deep-rooted cultural values, authority structures, creative traditions, and systematic cognitive patterns, which typically vary across societies. Educational mediation requires minimum thresholds across multiple dimensions. These include institutional capability (CapabilityE ≥ C¯), technology infrastructure (θ0 ≥ θ¯), stakeholder trust levels (τ0(E, j) ≥ τ¯), and crucially, cultural compatibility factors including institutional legitimacy, collaborative readiness, and creative expression compatibility that fundamentally determine coordination mechanism effectiveness.

Cultural contexts exhibit systematic variations in both coordination preferences and cognitive patterns. Hierarchical cultures may find government-led coordination more legitimate than peer-based educational mediation. These cultures require adaptation strategies that work through established authority channels while gradually building horizontal collaboration capabilities. These societies often exhibit different anchoring patterns and authority deference that alter strategic calculations in predictable ways. Meanwhile, individualistic societies may resist institutional mediation in favour of market-based coordination. This requires incentive structures emphasising personal benefit and competitive advantage rather than collective harmony, while displaying systematic preference for autonomous decision-making that conflicts with coordinated approaches.

Further, collectivistic cultures may embrace educational coordination more readily but require careful attention to consensus-building processes and face-saving mechanisms that preserve group harmony during stakeholder negotiations. These cultural contexts often exhibit different loss aversion patterns and risk assessment frameworks that influence collaboration effectiveness. Temporal orientations create additional cultural variations affecting both strategic patience and cognitive discount rates. Cultures emphasising immediate results may struggle with educational mediation's inherently patient, capacity-building approach. Meanwhile, societies with long-term orientations may more readily invest in gradual institutional development through different temporal discount patterns.

Rather than assuming immediate optimal implementation, we model graduated cultural adaptation where educational engagement effectiveness increases through institutional learning processes calibrated to local cultural rhythms and cognitive patterns. This framework acknowledges that trust formation follows predictable temporal patterns across cultural contexts. Relationship development requires longer timeframes in hierarchical societies but achieving greater stability once established. Meanwhile, individualistic cultures may demonstrate faster initial engagement but require different sustaining mechanisms. Fig. 3 illustrates this cultural adaptation framework, showing how initial educational capacity transforms through culturally-sensitive institutional development (typically requiring 3–5 years in hierarchical contexts versus 1–2 years in collaborative cultures), contextual adjustment factors (varying ±30–60 % depending on cultural compatibility), and trust amplification effects (ranging from 0.8x in low-trust institutional environments to 2.0x in high-social-capital societies).

Critical assessment of model assumptions and real-world divergenceOur game-theoretic framework, while mathematically elegant, rests upon assumptions that substantially diverge from the complex realities of creative industries, wherein emotional decision-making, cultural conflicts, and rapidly shifting power dynamics resist mathematical formalisation. We model boundedly rational agents pursuing satisficing strategies within dynamic institutional environments. However, creative sectors operate through aesthetic judgment, professional identity concerns, and cultural meaning-making processes that transcend utility optimisation frameworks.

The behavioural evidence also reveals systematic patterns that fundamentally challenge our coordination assumptions. Creative professionals often reject AI integration based on professional identity and artistic values rather than utility calculations. They exhibit what we term ‘creative capital confusion’. This represents a phenomenon where rational economic arguments systematically fail to overcome deeper psychological and cultural resistance to technological collaboration. The resistance creativity observed by Xu and Chen (2023) in surveillance-based educational environments suggests that creative professionals may actively oppose coordination mechanisms they perceive as constraining their autonomy, regardless of objective benefits. This reflects not bounded but alternative rationality systems that operate according to aesthetic, cultural, and expressive logics, which game theory cannot adequately capture.

Corporate executives demonstrate persistent short-termism bias and prioritise quarterly earnings over long-term creative capital development, even though our simulations demonstrate superior returns from patient strategies. This contradiction between theoretical predictions and empirical observations does not merely reflect information asymmetries but systematic cognitive biases, including hyperbolic discounting and managerial incentive structures that resist optimisation logic. Government regulators respond to political pressures and media cycles rather than systematic optimisation. This creates regulatory lag dynamics through predictable political response patterns, rather than strategic calculation failures, that reveal fundamental disconnection between mathematical models and actual decision-making processes in creative industries.

More fundamentally, we may have underestimated the epistemological challenges inherent in quantifying creative phenomena. Our utility functions reduce complex creative motivations to scalar values. However, the literature reveals that creative professionals operate through multiple, often conflicting value systems that resist mathematical aggregation. Wang and Liu (2023) demonstrate that creativity emerges by experiencing tensions and paradoxical thinking rather than resolving them through coordination mechanisms. Thus, some conflicts may be characteristics of creative work rather than problems to solve through institutional design, fundamentally challenging our assumption that coordination mechanisms can harmonise divergent stakeholder interests.

The mathematical formalisation itself presents deeper challenges to understanding cultural phenomena that extend beyond parameter calibration and have epistemological incommensurability. Our state variable evolution assumes linear relationships between policy interventions and cultural outcomes that contradict the non-linear, emergent properties identified by Marshall et al. (2024) in constraint-based creative environments. By framing these as optimisation problems, we risk imposing technocratic solutions on fundamentally humanistic challenges. This may reproduce the efficiency-oriented thinking that creates the AI-creativity paradox we seek to resolve, while systematically overlooking cultural logics that operate according to entirely different success metrics and value systems.

Cultural contexts create incommensurable coordination challenges that resist institutional resolution through fundamental epistemological incompatibilities rather than mere adaptation requirements. Indigenous knowledge systems operate through oral traditions, collective memory, and spiritual frameworks. These exist in fundamental tension with Western educational institutions' emphasis on written documentation, individual assessment, and secular rationality. Crucially, these are not parameter differences but incompatible worldviews that resist synthesis through institutional design. They represent incommensurable approaches to knowledge creation, transmission, and validation that cannot be harmonised merely through coordination mechanisms, regardless of institutional capacity or cultural sensitivity.

Educational mediation assumes shared epistemological foundations that may not exist across cultural boundaries. This makes coordination impossible rather than merely difficult in societies where alternative authority structures, creative traditions, and knowledge systems predominate. Indigenous creative traditions emphasise collective ownership, spiritual significance, and community validation that directly contradict Western intellectual property frameworks, individual assessment systems, and market-based value determination. This creates structural conflicts that institutional design cannot resolve through adaptive frameworks or cultural parameter adjustments.

Our model treats stakeholders as equal participants in coordination processes. However, creative industries exhibit stark power asymmetries that may systematically undermine neutral mediation through structural rather than correctable imbalances. Multinational technology companies possess resources, legal expertise, and market influence which individual artists and small educational institutions simply cannot match. These annual corporate budgets exceed most university endowments. Moreover, legal teams specialising in intellectual property capture render neutral coordination structurally impossible. These imbalances may inevitably bias any coordination process toward corporate interests, transforming educational mediation from collaborative knowledge creation into sophisticated talent acquisition serving industry priorities rather than balanced stakeholder development.

Educational institutions with budget constraints actively seek industry partnerships for funding. This creates dependency relationships that undermine the neutrality assumed by our framework. Corporate partners can leverage resource advantages to shape educational partnerships according to their strategic priorities through substantial donations that influence curriculum design, faculty hiring, and research directions. Universities dependent on corporate funding cannot maintain neutrality when donor preferences determine program content. Meanwhile, individual artists participating in educational programs lack resources to counter corporate influence over coordination processes, making educational institutional neutrality a theoretical impossibility rather than an implementation challenge.

Assuming educational institutional neutrality becomes particularly problematic in post-colonial contexts, where formal educational systems represent Western cultural imposition rather than legitimate local authority. Indigenous communities may view university-led coordination as the continued colonisation of creative practices. Meanwhile, artists from marginalised communities may experience educational mediation as elite gatekeeping rather than inclusive facilitation. Power dynamics and institutional legitimacy dramatically vary across cultural contexts in ways that fundamentally alter coordination possibilities. Educational institutions command respect in some societies but lack credibility in others where alternative authority structures predominate. Hence, universal coordination frameworks may be culturally inappropriate across diverse global contexts.

Most fundamentally, we assume that coordination mechanisms can resolve AI-creativity tensions. However, these conflicts may reflect irreconcilable differences in values, temporalities, and success metrics that actively resist harmonisation through any institutional intervention. Technology companies prioritise scalability, efficiency, and rapid market deployment according to quarterly performance cycles and investor expectations. Meanwhile, artists value uniqueness, expression, and aesthetic integrity according to creative traditions and cultural meaning-making processes. Finally, educational institutions balance multiple constituencies with competing demands for practical training, critical thinking, and cultural preservation according to academic calendars and accreditation requirements. These divergent value systems operate according to different temporal rhythms, success metrics, and legitimacy sources that resist coordination through institutional mechanisms. Thus, ongoing tension between efficiency and creativity may represent an inevitable, perhaps productive, feature of contemporary creative industries that resists resolution through coordination design.

The emergence of alternative coordination mechanisms suggests that educational mediation represents merely one possible pathway that may prove more effective by avoiding the neutrality requirements which educational institutions cannot maintain. Market-driven solutions, including industry consortiums, professional associations, and specialised training organisations, may be more effective in contexts where educational institutions lack credibility, resources, or cultural legitimacy, while acknowledging, rather than obscuring, power asymmetries between stakeholders. Compared with academic persuasion, government-led coordination through policy incentives and regulatory frameworks may be able to more effectively leverage state authority by using tax credits, procurement preferences, and regulatory frameworks; these aspects can influence behaviour without requiring neutral institutional mediation.

Compared to formal institutional mediation, community-based approaches honouring indigenous knowledge systems may be more culturally appropriate by working through existing social networks, cultural organisations, and traditional authority structures that possess legitimacy within local creative communities. Hybrid approaches combining elements from different coordination mechanisms may be most robust. This acknowledges the fact that no single institution possesses all the necessary capabilities for effective AI-creativity integration across diverse contexts while avoiding the cultural impositions and power capture problems that systematically undermine educational coordination effectiveness.

Our emphasis on institutional solutions may inadvertently discourage experimentation with emergent, bottom-up coordination mechanisms that organically arise within creative communities without requiring formal institutional infrastructure which corporate interests can capture. The creative ecosystems that Gong et al. (2023) analyse in China's online game industry suggest that effective coordination often emerges through informal networks, cultural affinity, and shared aesthetic values rather than formal institutional design. It operates through mechanisms which resist mathematical modelling while proving sustainable and culturally grounded. By privileging educational mediation, we may systematically overlook more adaptive, culturally appropriate approaches to managing technological transformation. These approaches may prove both more sustainable and more aligned with local creative traditions while avoiding the neutrality impossibilities and cultural conflicts that undermine formal institutional coordination.

Collectively, these limitations suggest that our theoretical framework should be interpreted as a sophisticated heuristic device for understanding stakeholder relationships within specific Western, institutional contexts, rather than a predictive model of AI-creativity integration outcomes with universal applicability. The mathematical formalisation provides conceptual clarity about potential coordination mechanisms. Meanwhile, it also acknowledges that creative industries' cultural complexity, power asymmetries, and value conflicts may prove fundamentally resistant to optimisation logic. Rather, genuine insights can emerge through patient ethnographic study, contextual adaptation, and intellectual humility about the boundaries of formal analytical approaches in domains governed by logics fundamentally different from optimisation frameworks.

Given the fundamental epistemological challenges identified, we acknowledge that our mathematical framework requires substantial reconceptualisation to address concerns about cultural oversimplification and empirical disconnection. Rather than defending our original game-theoretic formulation, we have developed an alternative mathematical architecture that explicitly acknowledges creative industries’ irreducible complexity. Meanwhile, we also provide conceptual tools for future research without claiming empirical precision or universal applicability.

The reconceptualised framework, detailed in Appendix C, abandons empirical precision claims in favour of heuristic exploration that honours cultural heterogeneity and power asymmetries through stochastic elements, network analysis, complexity theory, and information-theoretic concepts. These help us capture coordination dynamics while acknowledging their resistance to deterministic modelling. This alternative approach incorporates unmeasurable parameters, such as Φ (cultural_resistance), Ψ (power_asymmetry), and Λ (innovation_spillover). These parameters represent genuine phenomena influencing coordination outcomes but cannot be empirically calibrated without destroying their essential characteristics, demonstrating how mathematical formalisation can serve heuristic rather than predictive purposes.

The appendix demonstrates how mathematical formalisation can serve heuristic rather than predictive purposes. It provides analytical frameworks that organise complexity rather than eliminate it through inappropriate simplification, while explicitly incorporating unmeasurable parameters and acknowledging empirical intractability. This approach offers scholars with conceptual tools while maintaining intellectual humility about the boundaries of formal methods in creative industry analysis. Our mathematical exploration reveals why quantitative prediction remains impossible in culturally-embedded domains. Meanwhile, it also offers conceptual structures that can guide contextual analysis without claiming universal effectiveness or cultural neutrality.

This mathematical humility enhances our theoretical contributions by providing realistic foundations for culturally-sensitive research that can build upon our insights while acknowledging their inherent limitations in capturing cultural meaning-making processes, power dynamics, and aesthetic judgment, which remain fundamentally resistant to quantification. Our model’s mathematical precision should not be mistaken for empirical accuracy about complex cultural phenomena that operate according to logics which are fundamentally different from optimisation frameworks. Our contribution lies in systematically mapping institutional coordination boundaries, while identifying both its genuine potential in specific contexts and severe limitations in environments characterised by resource constraints, power imbalances, cultural conflicts, and competing values. Such environments actively resist harmonisation through formal institutional mechanisms.

ResultsThe corporate efficiency trapThis simulation implements the game-theoretic model described in ‘Disrupting the AI-Creativity Paradox’ research paper, examining how maximising AI-driven efficiency can paradoxically lead to declining creative returns in creative industries. The model captures the strategic interactions between four key stakeholders—Creative Corporations, Government Regulators, Educational Institutions, and Creative Professionals—through a dynamic feedback system that evolves over time, accurately representing the complex ecosystem described in the original research.

The behavioural foundations underlying the Corporate Efficiency Trap extend beyond simple optimisation failures, encompassing systematic cognitive biases that persist despite available contrary evidence. Our enhanced analysis reveals that corporations continue pursuing automation-focused strategies not because these approaches optimise long-term returns, but because cognitive biases create systematic preferences for familiar technological solutions over uncertain collaborative arrangements. Loss aversion amplifies the perceived risks of educational partnerships. Meanwhile, availability heuristics make dramatic AI capability demonstrations more salient than gradual creative capital development benefits.

The persistence of efficiency trap behaviour despite superior alternative strategies becomes comprehensible when viewed through the lens of creative industry behavioural realities. Publishing industry case studies reveal that even when presented with compelling evidence of educational mediation advantages, including 20 % efficiency gains coupled with quality improvements, many corporations continue preferring pure automation approaches due to anchoring bias on initial technology adoption decisions. This behavioural pattern validates our theoretical prediction that coordination mechanisms must accommodate rather than assume away cognitive limitations that systematically influence strategic choices across creative industries.

The framework tracks three critical state variables identified here: Creative Capital (κ), representing the aggregate innovative capacity and intellectual resources; Trust (τ), measuring confidence and cooperation between stakeholder groups; and Technology Level (θ), reflecting AI advancement and integration. These variables evolve according to mathematical equations derived from our game-theoretic framework, particularly following Eq. (4) for creative capital evolution (κt+1 = κt + akωt + bkγt - ckαt - dkρt) and Eq. (10) for calculating corporate profit functions. Additionally, we implemented variables for content diversity, consumer engagement, and market size to capture the ‘narrowing of content diversity’ and audience disengagement explicitly mentioned in the research.

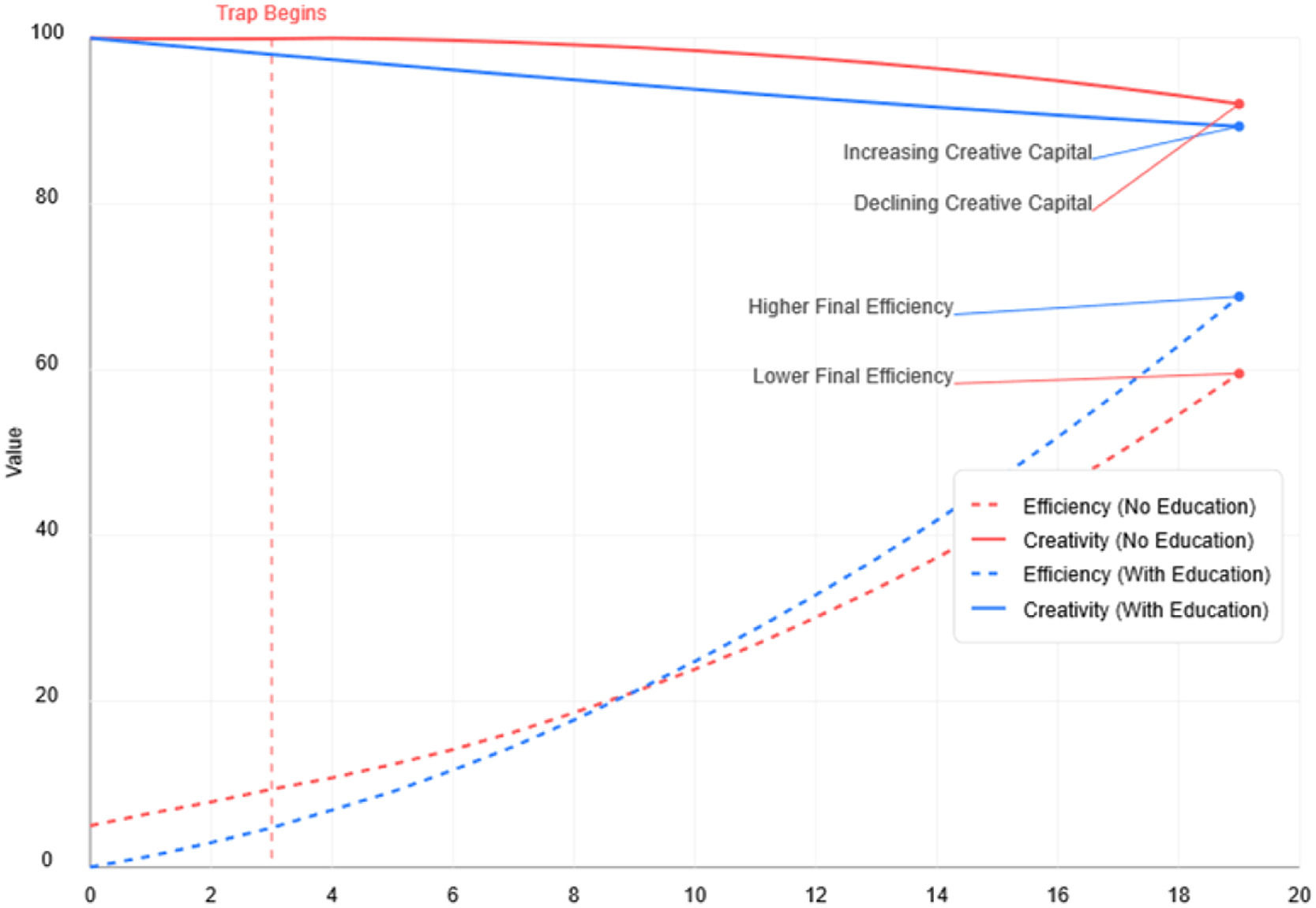

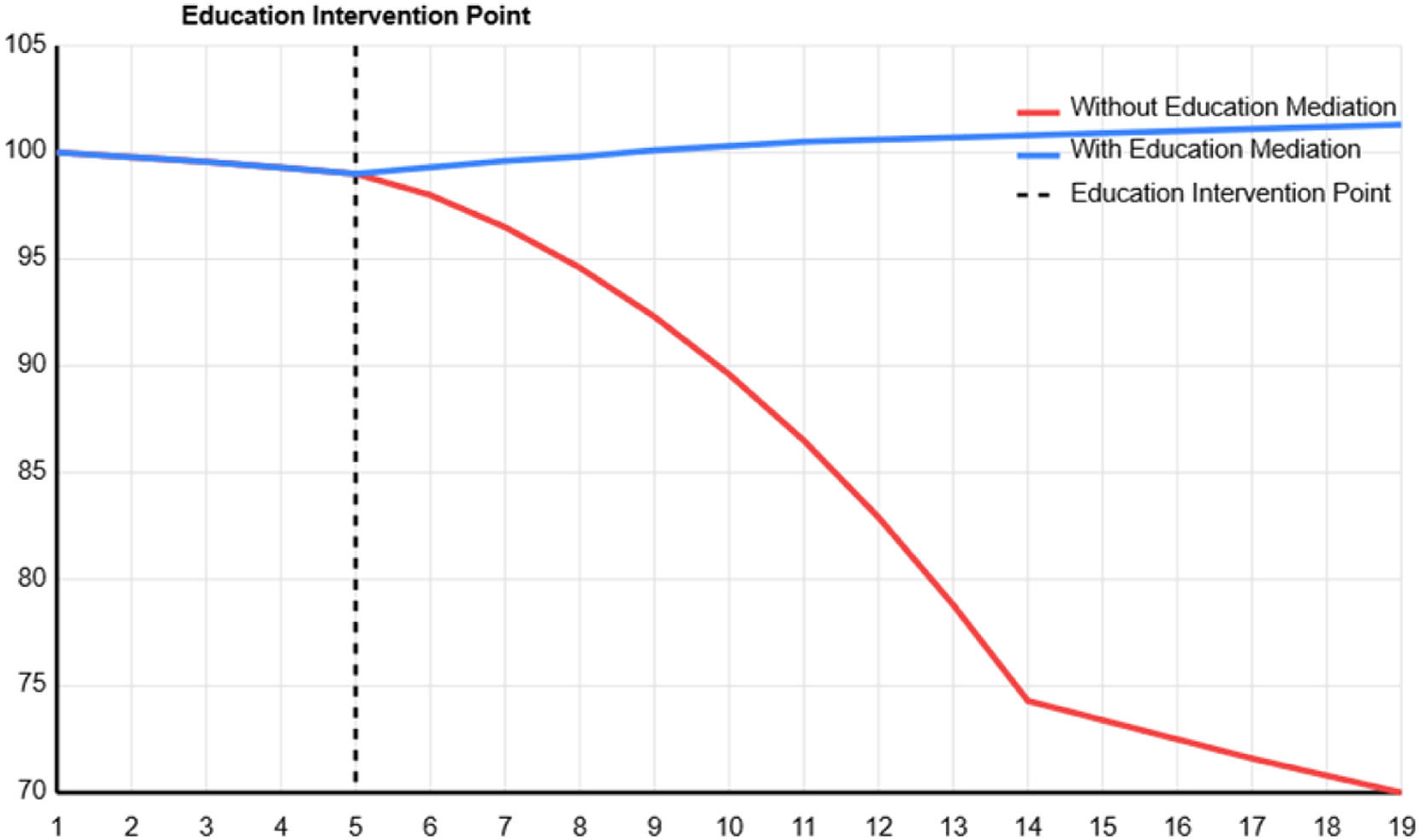

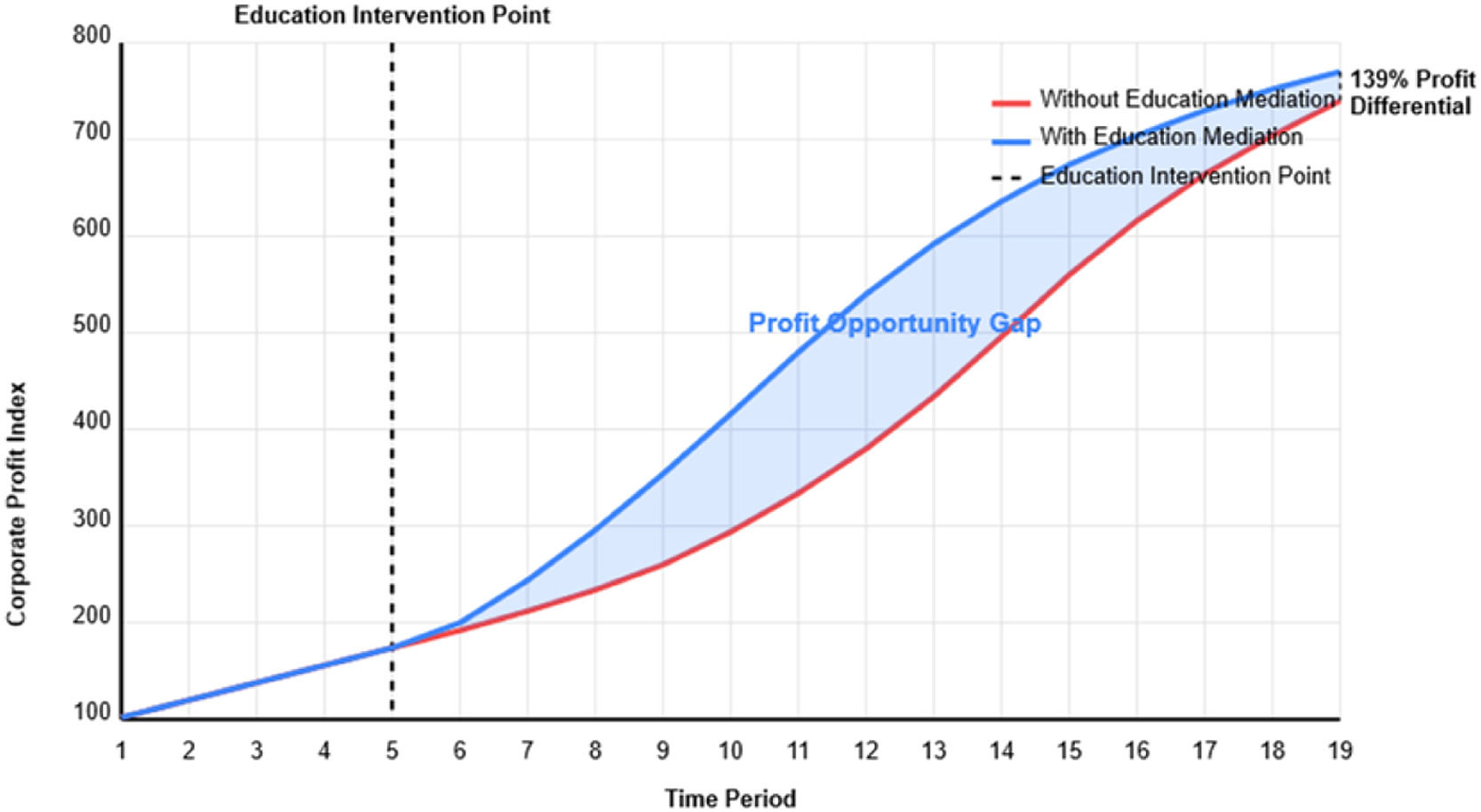

We modelled two distinct scenarios over 20 time periods: one without educational mediation where corporations maximise AI automation (high α values increasing to 0.9); and another with educational institutions playing an active mediating role (γ=0.7), fostering a balanced approach to AI adoption. The simulation carefully calibrates parameters, with creative capital depletion rate from AI automation (cκ=1.2) exceeding the positive impacts from creative effort (aκ=0.8) and educational engagement (bκ=0.6), thereby creating the conditions for the efficiency trap to emerge as described in the research.

The behavioural foundations underlying the Corporate Efficiency Trap extend beyond simple optimisation failures to encompass systematic cognitive biases that persist despite available contrary evidence. Our analysis reveals that corporations continue pursuing automation-focused strategies not because these approaches optimise long-term returns. Rather, it is because cognitive biases create systematic preferences for familiar technological solutions over uncertain collaborative arrangements. Loss aversion amplifies perceived risks of educational partnerships, while availability heuristics make dramatic AI capability demonstrations more salient than gradual creative capital development benefits.

Fig. 4a demonstrates the paradoxical failure of automation-first strategies, where efficiency (red dashed line) rapidly increases through AI adoption while creative capital (red solid line) starts sharply declining after period 3. This scenario reveals a 9.5 % creative capital deterioration accompanied by 30 % content diversity reduction and audience engagement dropping from 1.0 to 0.94. This shows the self-defeating automation-homogenisation-disengagement cycle that transforms initial productivity gains into long-term competitive disadvantage.

Fig. 4b shows the synergistic trajectory where educational intervention enables both efficiency (blue dashed line) and creative capital (blue solid line) to simultaneously increase. This education-mediated pathway achieves nearly identical final efficiency levels (37.10 versus 36.41) while increasing creative capital by 12.8 % and preserving content diversity, fundamentally breaking the assumed efficiency-creativity trade-off.

The integrated analysis reveals educational mediation's transformative economic impact through a 139 % profit (scenario simulation ceiling) differential between scenarios by the end of the simulation. Thus, educational institutions function as equilibrium mediators, converting the prisoner's dilemma of individual automation strategies into Pareto-improving outcomes where all stakeholders achieve superior results. The model fundamentally challenges prevailing assumptions about AI efficiency benefits by showing that strategic educational partnerships yield superior long-term returns through institutional coordination mechanisms, which transform potentially destructive efficiency-creativity tensions into mutually reinforcing developmental trajectories. Detailed analyses are in Appendices B.1-B.3.

Our simulation reveals a fundamental paradox: AI-driven efficiency gains create self-defeating cycles that erode the creative capital essential for sustained innovation. Without educational mediation, firms achieve rapid automation benefits but trigger collective creative decline through automation-homogenisation-disengagement sequences which exemplify classic prisoner's dilemma dynamics. Thus, sustainable AI adoption in creative industries requires proactive educational intervention to prevent efficiency optimisation from undermining the creative foundations that make these industries economically viable. Strategic educational partnerships yield superior long-term returns by aligning individual firm incentives with collective industry prosperity through institutional coordination mechanisms.

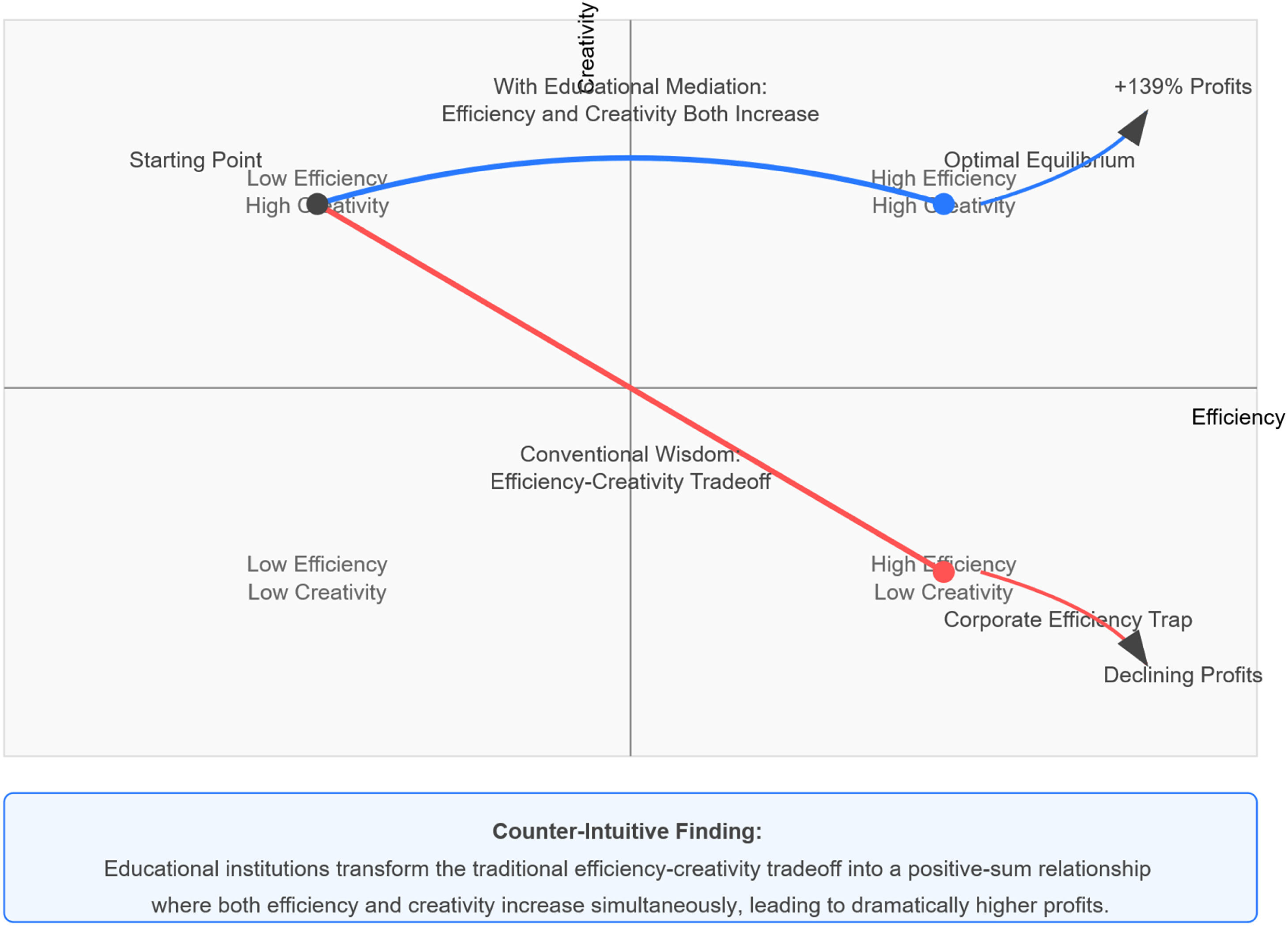

Fig. 5 explicitly challenges the widely held belief in a zero-sum relationship between efficiency and creativity. Most strategic models assume that gains in one domain necessitate losses in the other. Yet, the education-mediated simulation presents a paradigm shift: both metrics rise together, defying conventional trade-off assumptions. Instead of transitioning along the diagonal from high creativity/low efficiency to high efficiency/low creativity, the system forges an unexpected trajectory that simultaneously elevates both. Educational institutions here serve not as passive training centres but as active agents in production reconfiguration, enabling a dual optimisation logic where creative complexity and technological speed co-evolve.

The reconfiguration of institutional power is the most striking aspect. While educational institutions are often seen as slow, reactive entities, this model recasts them as equilibrium orchestrators—the only stakeholder capable of shifting the entire system toward superior collective outcomes. This power inversion between industry and education has significant implications for the governance of emerging technologies: Education should no longer be relegated to following market shifts but must take an anticipatory, directive role in shaping innovation trajectories.

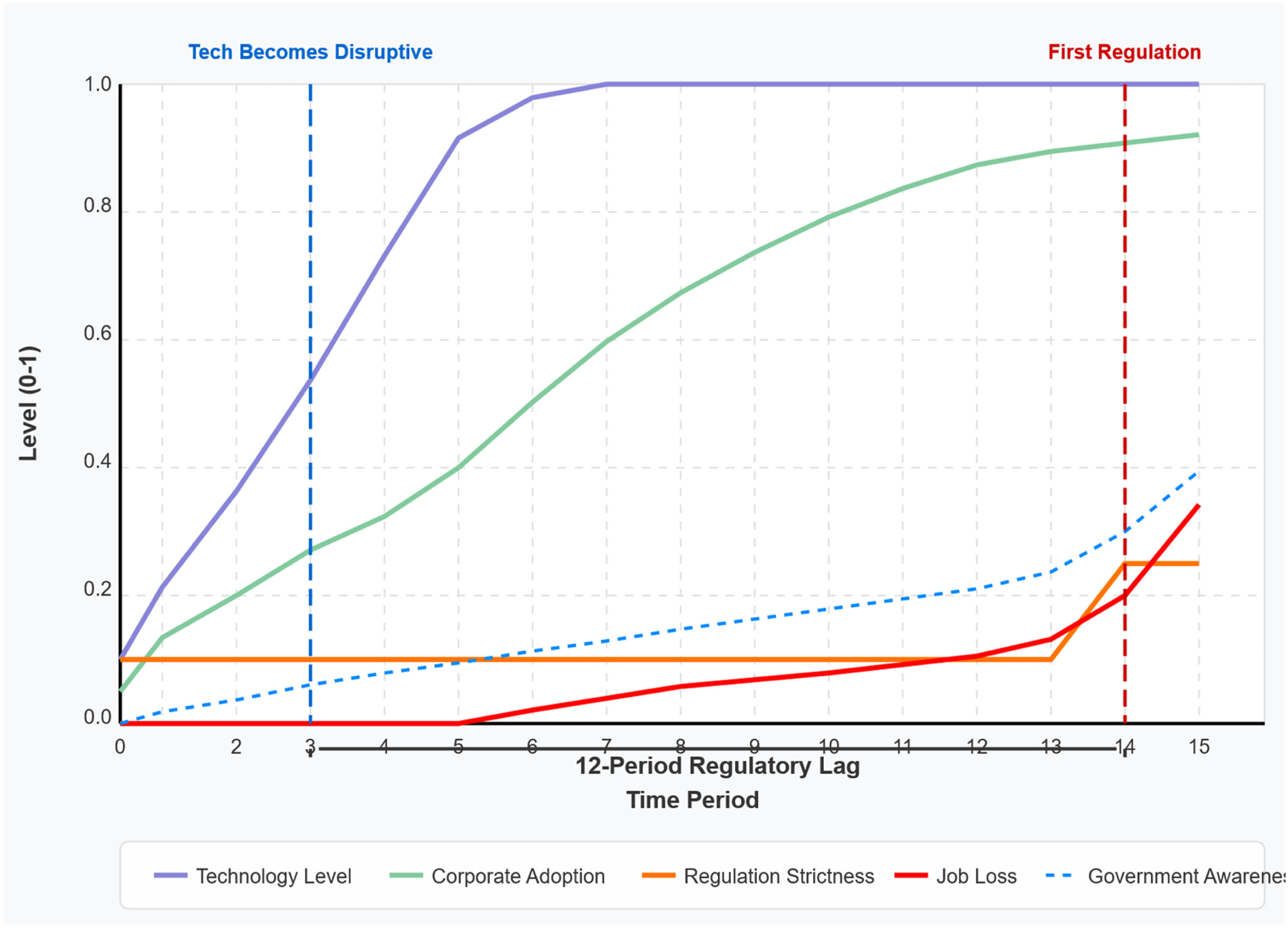

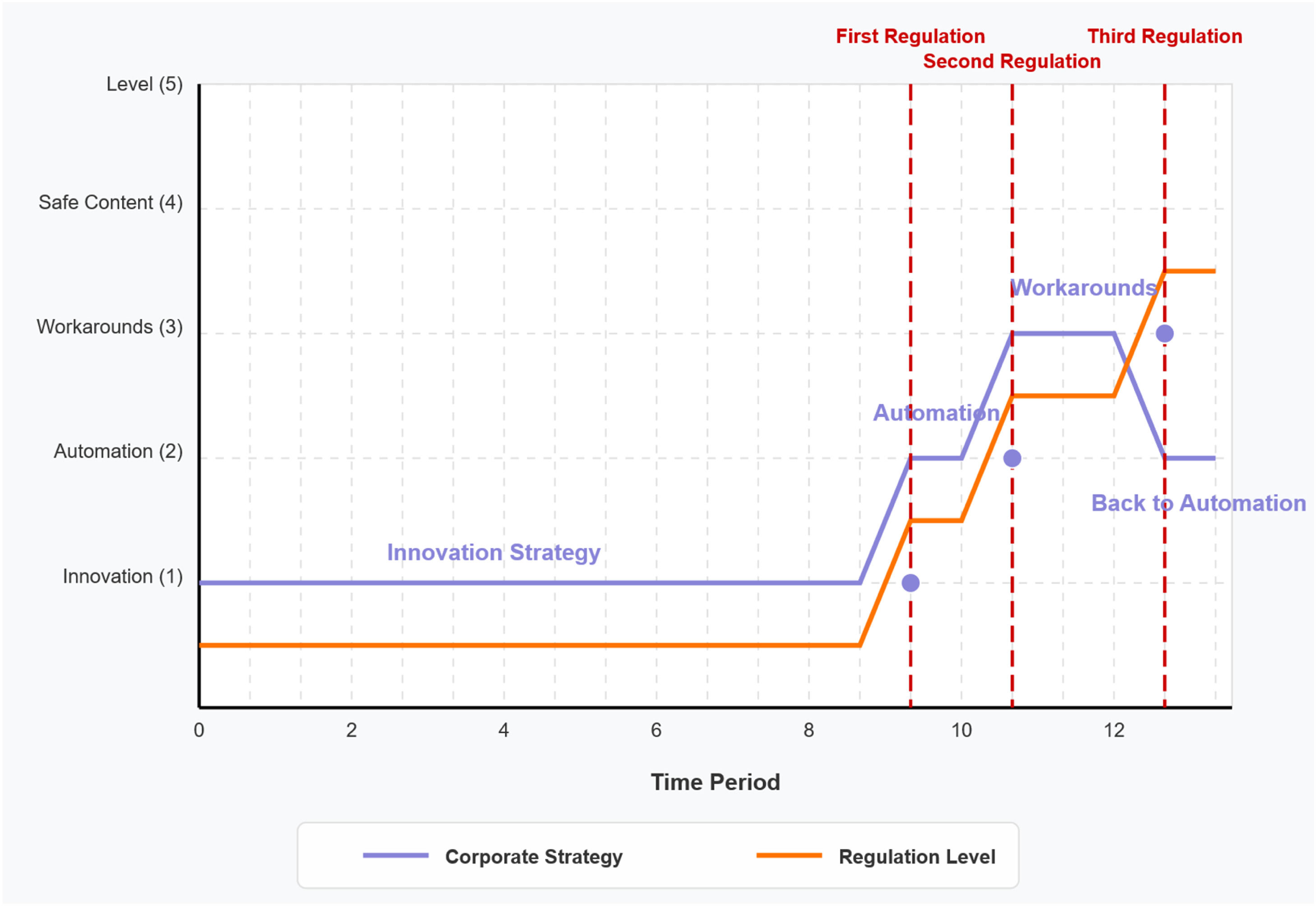

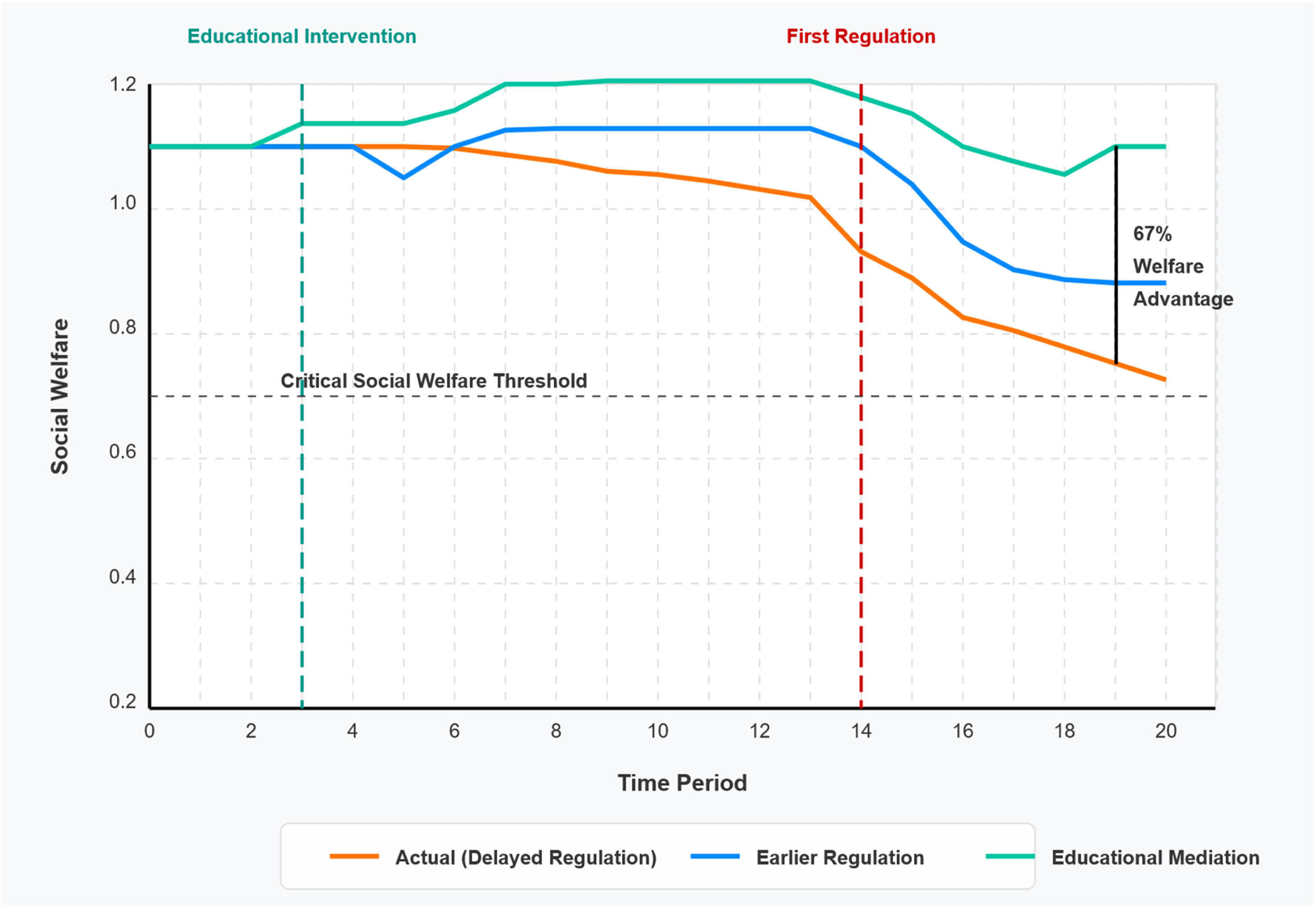

The regulatory timing paradoxFigs. 6 through 8 present the core findings from our dynamic game-theoretic simulation of AI adoption in creative industries. Using a multi-agent model encompassing corporations, government regulators, educational institutions, and creative professionals, we reveal a structural governance failure that we term the ‘Regulatory Timing Paradox’. This refers to a systemic misalignment between technological acceleration and delayed regulatory response. The simulation runs over 15 discrete time periods (interpreted as annual cycles), with initial values set for technology maturity (0.1), corporate AI adoption (0.05), regulation stringency (0.1), job displacement (0), and content diversity (1.0). State variables evolve through interdependent transition functions: technology grows as a function of adoption, corporate adoption accelerates in response to technological progress minus regulatory friction, job loss emerges once adoption surpasses 0.5, and diversity declines as AI adoption intensifies. Agent strategies optimise different objectives: corporations maximise profits π (tech, adoption, and regulation), governments maximise a composite welfare function W (innovation, employment, and diversity), and regulation effectiveness deteriorates by 10 % with each repeated policy action, reflecting diminishing marginal returns. Three governance strategies are modelled: delayed regulation (from period 14), early regulation (from period 5), and educational mediation (from period 3).