Global energy challenges have highlighted the importance of open innovation, which facilitates the development of efficient energy solutions through collaboration and knowledge sharing. However, owing to the increasing diversity of the energy open innovation ecosystem and the lack of standardized datasets, navigating the ecosystem and identifying potential opportunities for open innovation remain challenging. As a solution, we present a large-scale network modeling and embedding-based method called the Navigator of Energy Open Innovation Networks (NEON). First, scientific literature in the energy field is collected, and its metadata and textual information are systematically preprocessed. Specific topics in the energy field are identified using energy-specific pre-trained language models and density-based clustering. Then, a large-scale network is constructed to represent the energy open innovation ecosystem, incorporating papers, organizations, nations, topics, and their interrelations. Research collaborations are represented in the triplet form. Finally, network embedding techniques are applied to identify potential collaboration partners and research topics. Our case study, involving 149 nations, 6104 organizations, 88,727 papers, and 63 topics, confirms the effectiveness of the proposed approach in exploring complex energy open innovation ecosystems.

Global energy issues, intensified by climate change and resource depletion, necessitate the development of diverse and innovative technologies and solutions, thus highlighting the critical importance of open innovation (de Paulo & Porto, 2017; Meckling et al., 2022; Tabor et al., 2018). As a key mechanism of open innovation, collaboration among organizations at the international level facilitates sharing of knowledge and resources, thereby overcoming the limitations faced by individual organizations, such as constrained resources, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of subject matter expertise (Huizingh, 2011; Lee et al., 2010; Storch de Gracia et al., 2018). Prominent global initiatives, including Mission Innovation, the European Union’s Horizon 2020, and the U.S. ARPA-E programs, have been instrumental in fostering global collaboration in energy open innovation by facilitating the exchange of innovative ideas and technologies (Colombo et al., 2019; Goldstein et al., 2020; Malhotra & Schmidt, 2020; Salmelin, 2013).

However, identifying opportunities for global collaboration in energy open innovation ecosystems remains challenging because of the inherent complexity of these opportunities. This complexity stems primarily from the heterogeneity of diverse actors and their relationships (Battistella et al., 2018), the nonlinearity of interactions among participants (Leydesdorff et al., 2013; Yun et al., 2017), and the evolutionary nature of open innovation ecosystems (Poutanen et al., 2016). Consequently, existing innovation system frameworks, such as the sectoral innovation system, triple helix model, and national innovation system, present several practical limitations when applied directly to the context of energy open innovation ecosystems.

- •

First, the energy field is highly comprehensive and lacks standardized definitions or a clear consensus on the classification of its subfields, making the identification of coherent sections challenging (Kim et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019). Consequently, frameworks such as the sectoral innovation system, which relies on delineated technological or industrial boundaries, encounter major limitations when applied to the energy domain because of the fragmentation of knowledge and technology across diverse subfields. As interdisciplinary approaches become more prevalent, and energy-related challenges become increasingly complex, new subfields continue to emerge, further amplifying the need for a consistent and adaptive framework for classification in the energy sector.

- •

Second, although various stakeholders, such as corporations, universities, and research institutes, actively participate in the energy open innovation ecosystem, the lack of standard datasets makes it difficult to identify the status, roles, and contextual relationships of individual organizations. This presents a major challenge to analyzing open innovation ecosystems from the perspective of actor-centered innovation system frameworks, such as the triple helix model, which conceptualizes innovation as the result of dynamic interactions among university, industry, and government actors (Greco et al., 2017; Sagar & Holdren, 2002). As the number and diversity of participants (e.g., organizations and nations), subfields, and their interconnections continue to grow within the energy ecosystem, this issue is becoming increasingly important.

- •

Third, the energy sector inherently demands extensive international collaboration and is characterized by frequent cross-border activities, ranging from global university-industry partnerships and multinational research and development (R&D) projects to international funding programs. Consequently, organizations and experts struggle to identify suitable worldwide partners and track rapidly evolving R&D trends when relying on region-centered frameworks. As this framework focuses on the networks of institutions, rules, and relationships within a single nation, it cannot fully capture or support the transnational flow of knowledge, capital, and talent that underpins today’s global energy open innovation ecosystem. As international engagements proliferate and inter-organizational networks become more complex, there is an urgent need for new data-driven frameworks that can continuously monitor and analyze cross-border innovation dynamics.

To overcome these challenges, we suggest the use of Navigator of Energy Open innovation Networks (NEON), a new approach to effectively analyze energy open innovation ecosystems using large-scale network modeling and the latest network-embedding techniques. Our research questions are as follows:

- (1)

Which research topics does an energy open innovation ecosystem address?

- (2)

How do national and organizational priorities differ within an energy open innovation ecosystem?

- (3)

Given a target organization, how can potential collaborative opportunities be identified?

To obtain answers, we designed the proposed approach comprising four discrete steps: (1) collection of scientific literature in the energy field and systematic preprocessing of the metadata and textual information; (2) development of an automatic topic detection model that utilizes energy-specific pre-trained language models (PLMs) and density-based clustering to effectively interpret domain-specific textual information and reveal groups of similar documents representing individual energy topics; (3) construction of a large-scale network representing energy open innovation ecosystems, which comprise papers, organizations, nations, topics, and their interactive relationships, offering a snapshot of research collaborations in the form of triplets; (4) application of network embedding techniques to this network to facilitate the identification of potential research collaboration partners or topics.

We applied the proposed approach to support the navigation of potential collaboration partners and new research topics in an innovation ecosystem. We used the Web of Science (WoS) and Global Research Identifier Database (GRID) to obtain high-quality datasets from scientific literature and official organizational information. Our case study, involving 149 nations, 6104 organizations, 63 topics, and 88,727 papers, demonstrates the effectiveness and feasibility of navigating complex energy open innovation ecosystems and identifying opportunities for collaboration. Our empirical results include detailed operational descriptions from data collection to result validation, which could guide the practical implementation of the proposed approach. The proposed approach is expected to facilitate the systematic and continuous monitoring of open innovation ecosystems, ensuring high efficiency in terms of both time and cost while delivering substantial benefits. The systematic process and quantitative outcomes can help experts and policymakers in establishing strategic decision-making in the era of information proliferation.

Literature reviewDefinition and concepts of open innovationOpen innovation is a paradigm wherein organizations strategically leverage and integrate internal and external knowledge to accelerate innovation (Chesbrough, 2006). The traditional innovation strategy, known as closed innovation, protects intellectual property, secures excellent global talent, and enables competition with the outside world (Almirall & Casadesus-Masanell, 2010). On the contrary, open innovation brings organizations closer to opportunities for radical innovation that can solve urgent global issues through knowledge sharing and cooperation with external colleagues (Chung et al., 2021b; Greco et al., 2017). Several aspects are considered in the open innovation ecosystem, which can be summarized into three components: (1) regions where innovation occurs, e.g., local, national, and international levels (de Paulo & Porto, 2017); (2) participants, such as research institutions, industry, government, non-profits, and citizens that collaborate to generate innovation in current or new markets (Kankanhalli et al., 2017); (3) sectors representing a set of activities that link groups of products and share common knowledge centered on a specific domain and demand (Kim & Lee, 2008; Malerba, 2002).

Several models of open innovation depend on the components of the innovation ecosystem. First, from a regional perspective, the national innovation system is a representative open innovation system wherein academic, business, and public actors interact to address national needs (Balzat & Hanusch, 2004). Notwithstanding various definitions, there is a consensus that the national innovation system is a dynamic network of science, technology, socioeconomics, and the environment, where heterogeneous actors seek to achieve sustainable growth and development through inter- and intra-national collaborations (Li et al., 2023). When this system is narrowed down to regional government units that manage a state or province, it is called a spatial or territorial innovation system (Chung, 2002). Recently, owing to accelerated globalization and blurred national boundaries, discussions have expanded to include global innovation systems (Lee et al., 2020). Second, from the participants’ perspective, the triple helix was the most representative model. This model represents an open innovation system driven by university-industry-government relations, emphasizing communication and collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers (Leydesdorff, 2000; Leydesdorff & Etzkowitz, 1998). The triple helix model can help solve public economic and social problems with university knowledge and industrial resources through government-supported projects, thereby promoting national and regional development (Galvao et al., 2019). Recently, quadruple and quintuple helix models have emerged, embedding the triple helix by adding civil society and the natural environment of society (Carayannis et al., 2012). Finally, from a sectoral perspective, a sectoral innovation system fosters open innovation in each technological domain. The sectoral innovation system is designed to provide a multidimensional, integrated, and dynamic view of sectors and is characterized by an industry-specific knowledge base, technologies, inputs, and (potential or existing) demand (Malerba, 2002). In this system, firms (e.g., users, producers, and input suppliers) and non-firms (e.g., universities, research centers, government agencies, and financial institutions) interact through communication, exchange, cooperation, competition, and command (Beije & Dittrich, 2008). Although these systems have their own systematic characteristics as do complex adaptive systems, they can serve as illustrative examples of open innovation ecosystems because of their inherent features (e.g., knowledge openness, collaborative innovation, and dynamic adaptability). Accordingly, a national innovation system comprises multiple sectoral systems of innovation, whereas one or more helix models may shape both national and sectoral innovation systems (Chung, 2002).

Energy open innovation ecosystemsThe energy field is a comprehensive system that requires advanced science and technology and involves complex relationships among stakeholders. The current energy field demands high-cost, high-risk R&D (Mihić et al., 2018), convergence with digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, internet of things, blockchain, and digital twins (Onile et al., 2021; Raza & Khosravi, 2015; Wang & Su, 2020; Zeadally et al., 2020), and the reinforcement of global government regulations and policies (He et al., 2016; Tagliapietra et al., 2019) to solve critical challenges such as renewable energy integration, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), hydrogen economy development, and nuclear waste management (De La Peña et al., 2022; Solomon & Krishna, 2011). These issues cannot be solved by a single entity in the energy ecosystem; rather, addressing them requires knowledge exchange and international collaboration between nations and organizations.

Scholars have empirically discussed the introduction of open innovation in the energy sector (Dall-Orsoletta et al., 2022; Song et al., 2020; Van Lancker et al., 2016). Data-driven quantitative studies have provided valuable insights into the national and organizational collaboration from a domain-specific perspective. For example, Guan and Liu (2016) constructed knowledge and collaboration networks through the co-occurrence of patent classification codes and invention organizations and investigated the impact of direct and indirect ties and network efficiency on exploitative and exploratory innovations in organizations. Aleixandre-Tudó et al. (2019) explored the production, funding, and collaboration in the field of renewable energy with bibliometric and social network analysis techniques based on information provided by an academic database and found that wind power research accounted for the largest proportion and that the triangle formed by the United States, China, and the European Union was the most important collaboration structure. de Paulo and Porto (2017) forecast future international collaborations based on the growth of partnerships and identified clusters for regional, national, and international collaborations using social network analysis in the field of solar energy. Liu et al. (2021) constructed a patent collaboration network for the wind energy industry in China and analyzed the network structure and major patentee types from the perspective of network evolution.

Nevertheless, effectively analyzing the landscape of open innovation ecosystems in the energy field remains challenging due to the following key issues:

- (1)

Considering that the energy field is comprehensive and that there are no standards or consensus on the definition and classification of its subfields, it is difficult to identify the sectors. Prior studies have used complex queries composed of expert-selected domain-specific terminologies or jargon for sector analysis; however, this human-centric approach is costly, time-consuming, and difficult to reproduce. To address this limitation, we developed an energy-specific topic-identification model. By introducing a PLM trained on an energy-related corpus, we identified energy research topics based on a contextual understanding of domain knowledge.

- (2)

Although the clear identification of organizations and their nationalities is important for open innovation analysis, the relevant data do not provide standard names or structured information. Recently, as the volume and diversity of participants (i.e., organizations and nations), subfields, and their relations in the energy ecosystem have increased, organization-level or nation-level analyses have become difficult. In this study, we analyzed the energy ecosystem from subfield, organizational, and national perspectives by systematically linking well-established academic and institutional identification databases.

- (3)

Organizations and experts face major challenges in navigating the vast open innovation ecosystems in the energy field, finding suitable collaboration partners, and planning effective R&D strategies to solve pressing energy issues through open innovation. To address this limitation, we adopted network-embedding techniques to recommend collaboration opportunities to organizations based on a heterogeneous network and triplet structures representing the energy open innovation ecosystem and collaborations, respectively.

Fig. 1 illustrates the proposed NEON approach, which comprises four key steps: (1) collection and preprocessing of energy research papers; (2) identification of research topics using energy-specific PLMs and density-based clustering; (3) construction of a large-scale network representing the global energy open innovation ecosystem; (4) exploration of collaboration opportunities through network-embedding techniques.

Data collection and preprocessingHigh-quality scientific research papers are acquired from various academic databases, such as WoS and Scopus, which provide structured data on peer-reviewed scientific articles (Fig. 1a). The collected information comprises textual information and metadata. Textual information includes the titles and abstracts of each article, while metadata includes publication year, journal, author, and affiliation information. In particular, the academic database provides well-established categories for academic journals, which facilitate the filtering of papers on a particular topic.

To analyze the open innovation ecosystem, the nationality of the organizations for each article should be curated. WoS provides this information along with the abbreviations for each organization. For instance, the organization “California Institute of Technology” is represented as “CALTECH,” and “Beijing Institute of Technology” is represented as “Beijing Inst Technol.” As shown in these two examples, abbreviations are irregular expressions in natural language, making it difficult to associate them with the original names of organizations. To eliminate this issue, we employ the GRID database (https://www.grid.ac/), which provides the official names of research organizations, their nationality, and their organization type. By integrating these two databases, we match the organizational names in the WoS dataset with their most similar counterparts in the GRID database. Specifically, we utilize string comparison algorithms such as Jaccard similarity, Levenshtein distance, and Jaro-Winkler similarity for each pair of organization names.

Energy-specific topic detectionTo effectively identify topics from a large number of documents, we develop an energy-specific topic detection model using PLMs (Fig. 1b). As the texts of scientific articles are inherently unstructured, they must be converted into dense embedding vectors for analysis. In this study, we adopt PLMs based on bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) for document embedding (Devlin et al., 2019), as their ability to understand context and recognize tokens has been demonstrated in various domains (Chung et al., 2025). EnergyBERT (https://huggingface.co/UNSW-MasterAI/EnergyBERT), which is specialized for the energy sector and is trained on a corpus of 1.2 M energy-related research papers and technical documents, is employed in this study to capture the nuances and technical language of our energy paper dataset. Consequently, the texts of the scientific papers are transformed into 768-dimensional embedding vectors, in which their semantic meanings are conserved.

Next, we utilize density-based clustering, which does not require the number of topics to be determined, considering the diversity of subfields within the energy materials sector (Choi & Lee, 2024b). Before clustering, we apply uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP), a metric learning-based dimensionality reduction technique, for improved computational efficiency. Based on the reduced embedding, we apply the hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN), a density-based clustering algorithm, to identify clusters of similar documents using unsupervised learning. Similar groups of densely clustered documents in the embedding space are identified as distinct topics. The clusters are labeled using information from the main papers closest to the centroids of the corresponding topics. Specifically, we examine the titles of major papers and the most frequently used keywords to identify coherent content for each cluster.

Energy open innovation network constructionA real-world open innovation ecosystem includes multiple stakeholders, papers, and topics that involve various events. Research collaboration between various organizations and countries is a representative form of open innovation, and scientific papers are representative outcomes of these activities. The topics of these papers indicate the research aims and directions of the research organizations and countries involved. To effectively analyze these open innovation ecosystems, we construct a heterogeneous network in which various types of entities (e.g., topics, papers, organizations, and countries) and their interrelationships are represented as nodes and edges (Fig. 1c). This network comprises eight types of relationships defined by node types: topic–paper, topic–organization, topic–nation, paper–organization, paper–nation, organization–organization, organization–nation, and nation–nation. For example, each paper is associated with a research topic based on the topic detection results. Organization nodes are linked to their respective papers, and each organization is connected to its national node according to the curated nationality information. In this network, research collaborations among organizations are represented as triplets consisting of two organization nodes and one topic node connected to each other (Fig. 2). A triplet (red lines in the sample network) indicates that two organizations, “Gyeongnam National University of Science and Technology” (O1330) and “Korea Institute of Toxicology” (O4190), published research papers through a research collaboration to solve a research problem related to the topic “Waste heat recovery” (T4).

Prospective analysis for potential collaborationWhen planning research collaboration through open innovation, it is important to decide with whom to collaborate and what to research. Thus, we provide a prospective analysis of innovation ecosystems for research collaboration using triplet structures and network-embedding techniques (Fig. 1d). We address two key recommendation tasks—(1) identifying suitable collaboration partners with the necessary expertise for a topic of interest, and (2) selecting feasible research topics for a given collaborating organization.

First, we transform each node in the open innovation network into dense embeddings using network-embedding techniques to effectively analyze the status and context of each node in the ecosystem. Various network-embedding techniques, such as DeepWalk (Perozzi et al., 2014), Node2Vec (Grover & Leskovec, 2016), and TransE (Bordes, Usunier, Garcia-Duran, Weston, & Yakhnenko, 2013), can be used. Network embedding learns the structure of a complex network and transforms it into a multidimensional vector space, thereby effectively capturing the local and global structures of the network and expressing the latent characteristics of nodes as dense vectors (Choi & Yoon, 2022). In addition, as network embedding can reduce the computational complexity of analyzing large-scale networks, it can perform downstream tasks, such as node classification, link prediction, and community detection, more efficiently. Second, we define the recommendation scores based on the embedding similarity between nodes in the network. We address two recommendation tasks for users: (1) recommending new collaborators given a predefined research topic, and (2) recommending new research topics given a predefined collaborator. The weights are set to be identical but are adjustable according to the analysis context. There are two situations to consider when given a target organization. First, when the user (Ou) selects potential organizations (O) for collaboration on a specific research topic (Tt), it is more effective to prioritize the similarity between the target topic and candidate organizations rather than inter-organizational similarity. This approach allows for a more precise identification of suitable partners, as shown in Eq. (1):

Conversely, when the user explores potential research topics (T) for collaboration with a predefined partner (Oc), a greater weight can be assigned to the highest similarity score among the organization–topic pairs. This enables broader exploration of promising research areas, as expressed in Eq. (2):

ResultsDataData collectionWe used the WoS database, a globally recognized academic database, to acquire the necessary data. Compared to Scopus, WoS provides the advantage of collecting high-quality and peer-reviewed academic papers (Chung & Kim, 2024), as it evaluates scientific impact more strictly when indexing journals while having similar coverage in the fields of natural science and engineering, which are the fields we analyzed in this study (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016). Using journal categories and evaluation metrics managed by the WoS, we selectively collected scientific publications in the energy research field with high accuracy. Specifically, we focused on the “Energy & Fuel” category. For this category, we defined 29 target journals ranked in the first quartile based on their impact factors among the journals. For the filtering, language and document type were set to “English” and “Articles,” while the publication year of the papers was set as 2018 to 2022. Consequently, 94,199 papers were gathered on October 31, 2023, and 5472 noisy papers without bibliographic or textual information were excluded from the analysis. In total, 88,727 articles were included in this study. To validate the proposed approach, the data were divided into two periods (Fig. 3): Period 1 (from the first half of 2018 to the first half of 2020) for training and Period 2 (from the second half of 2020 to the second half of 2022) for validation.

Data pre-processingThe nationality of each organization was identified by mapping the organization names in our datasets to those in the GRID database with character-level Jaccard similarity (details on the results according to the string comparison algorithms can be found in Description A1 in Appendix). We accurately matched the organization names by calculating the similarity at the character level, rather than at the word level. This approach was effective even when the word order was different, diacritics were included, or the same object was referred to slightly differently depending on the language. For example, the names “University of Jan Evangelista Purkyne,” “Izmir Katip Celebi University,” and “Malatya Turgut Ozal University” in our dataset were well matched with the official names “Jan Evangelista Pukyně University,” “Izmir Kâtip Çelebi University,” and “Malatya Turgut Özal Üniversitesi” in the GRID database. The GRID used in this study is the latest version, version 19 (released on September 28, 2021).

Descriptive analysisThe number of papers increased over the entire period; therefore, the data size for Period 2 (n = 49,430) was slightly larger than that for Period 1 (n = 39,909). Interestingly, more than 90 % of the papers originated from nations participating in Mission Innovation, indicating the dominance of their research efforts in global energy issues (Gross et al., 2018; Meckling et al., 2022; Myslikova & Gallagher, 2020). We examined the effect of open innovation on the academic quality of research output. Specifically, we statistically compared the differences in average citation counts between papers with and without collaboration. Collaboration was addressed at both the national and organizational levels. We found that collaborative papers were more impactful across all types of collaborations (Table A1), consistent with previous research (Audretsch & Belitski, 2023; Caputo et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2012).

Fig. 4a shows the number of papers and organizations for each nation, and Fig. 4b depicts the collaborative relationships among nations participating in mission innovation. Excluding the EU, China (n = 43,647) accounted for more than half of the publications, followed by the US (n = 13,302), the UK (n = 7980), and South Korea (n = 5123). China hosted the largest number of organizations (n = 1048), followed by the US (n = 715), India (n = 519), and Japan (n = 222). As shown in Fig. 4b, Asian nations, such as China, India, and South Korea, primarily conducted research through domestic collaborations. In contrast, a large proportion of the collaborations in the EU, US, and UK involved other nations.

National-level overview of the collected data. (a) Number of papers and participating organizations from nations participating in Mission Innovation. (b) Collaboration status of nations participating in Mission Innovation, where the width of the arrow indicates the volume of collaborative papers published between the two nations.

To answer this research question, we developed an energy-specific topic-detection model using open-source Python libraries (e.g., Hugging Face and BERTopic). Specific parameters were determined according to the judgements of experts on the grid search results—the minimum size of each topic was 100, the number of top words was 10, the diversity was 0.5, the minimum cluster size was 10, the minimum number of samples was 1, the number of neighbors was 15, and the number of components was 5. Using the energy-specific topic detection model, 63 distinct energy research topics were identified from Period 1 papers, and the topics of Period 2 papers were inferred using the trained model. Two pieces of information were used to interpret the meaning of these topics. First, the documents closest to the centroid of each topic were identified. Second, frequent noun phrases were extracted from the titles and abstracts of the papers using the natural language processing Python spaCy Library (https://spacy.io/). This information was used as reference information by energy material experts and large language models [e.g., Claude 3.5 Sonnet (https://claude.ai/)] to determine the annotations. The resulting topic annotations are listed in Table A2.

To effectively navigate the topic landscape of energy papers, we plotted 63 topics in a two-dimensional space (Fig. 5). These topics are largely divided into energy storage, renewable energy, and bioenergy technologies. Energy storage included the largest topic, “Lithium-ion battery technology,” located in the center-left of the map, surrounded by similar topics on fuel cells and water splitting. Renewable energy topics located at the top of the map included solar cells, solar thermal, and wind power research topics. The bottom of the map contained bioenergy-related topics such as biofuel technologies and microbial engineering.

Results of energy research topic identification.

Next, we investigated the ranking of topic interests based on paper–topic information and tracked the changes in ranking over time (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6a, the number of papers published on 77 % of the topics increased between periods 1 and 2 (n = 49). Notably, 11 % of the topics (n = 7) exhibited more than a two-fold increase. The topic “Lithium-ion battery technology” had the highest number of publications across the entire period, followed by “Renewable energy economics.” “Renewable energy systems” ranked third overall in terms of the total publication count. As shown in Fig. 6b, its rank slightly improved from sixth in the first half of 2018 to third and fourth in the first and second halves of 2022, respectively. Conversely, the rank of “Perovskite solar cells” decreased from third in Period 1 to sixth in Period 2. The topic “EV battery management” ranked ninth in the total publication count and was one of the major topics with more than a two-fold increase in paper counts from Period 1 to Period 2. This topic, which received limited attention until the second half of 2020, emerged as a significant issue, reaching tenth place in the first half of 2021 and rising to fifth place in the second half of 2022. This trend suggests that with advancements in the electric vehicle technology, the development of batteries and battery management technologies, such as those addressing fire risk, has become increasingly critical (Deng et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019).

RQ2: how do national and organizational priorities differ within an energy open innovation ecosystem?For the two analysis periods, we constructed two large-scale networks that represented open innovation ecosystems. The network from Period 1 comprised 39,909 papers, 4742 organizations, and 141 nations, whereas that from Period 2 comprised 48,181 papers, 5312 organizations, and 145 nations. The number of topic nodes in both periods was the same. Based on network information, we analyzed organizational and national research interests. First, using the network for Period 1, we analyzed the interests of 10 major organizations with high eigenvector centrality, which quantitatively represents the influence of the nodes (Fig. 7a). The unique research interests of organizations were identified by comparing the topics associated with them. For example, only the “Helmholtz Association” focused on the topic “Bioenergy supply chain,” indicating active research on biomass production and supply (Szarka et al., 2021; Von Cossel et al., 2022), bioenergy conversion technology (Herrera et al., 2020; Lohani et al., 2021), and the optimization of bioenergy systems (Jan Müller et al., 2020; Maier et al., 2021; Schipfer et al., 2022). The results showed that US organizations tend to focus on general research topics that often overlap with the interests of other nations, while Chinese organizations have unique research interests such as “Vibration energy harvesting” (Dong et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018), and “Hydrogen storage materials” (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018).

Application of NEON to analyze organizational and national interests in energy research. (a) Identification of key topics of interest to major organizations during Period 1. (b) Visualization of the level of interest in key topics by nation during Period 1 based on the number of publications, where the values were normalized for each nation; the maximum interest is denoted by red and the minimum by yellow.

Similarly, we analyzed the interests of nations participating in Mission Innovation for the 10 topics with high eigenvector centrality, which are regarded as important in the global energy open innovation ecosystem (Fig. 7b). Nations in East Asia, North America, Oceania, and Africa are the most active in LIB research. In contrast, most European and South American nations showed increased interest in renewable energy economics. Among the three major nations, China and the US showed broad and balanced interest in various research topics, whereas the UK exhibited a particularly strong interest in topics related to electric vehicles (Küfeoğlu & Khah Kok Hong, 2020; Skeete et al., 2020). Similar insights were obtained using the Period 2 networks (Fig. A1).

RQ3: given a target organization, how can potential collaborative opportunities be identified?To answer this research question, we performed recommendation tasks using triplet structures and network-embedding techniques. Specifically, we suggested possible triplets consisting of two organizations and one topic with network embeddings from Period 1, which were validated using the data from Period 2. As a proof of concept, we tested organizations that published more than 10 papers in Period 1. DeepWalk was employed as the main model for network embedding owing to its effectiveness in learning local and global structures in large-scale networks (Qiu et al., 2018). The DeepWalk model was trained using the Python library Gensim, and the hyperparameters were optimized through a grid search based on recommendation performance. Specifically, the embedding dimensions were set to 128, walk length to 20, number of walks to 80, and the window size to 10. The similarity was measured using cosine similarity, and all weights were set to be the same. To utilize the recommendation results effectively, users must consider as many candidate topics and organizations as possible. To support this process, we provided descriptive information (e.g., the number of relevant papers, top-cited papers, major players, and keywords) and network indicators (e.g., network centrality and similarity measures) for the candidates (details of the centrality measures can be found in Description A2 in Appendix and Table A3).

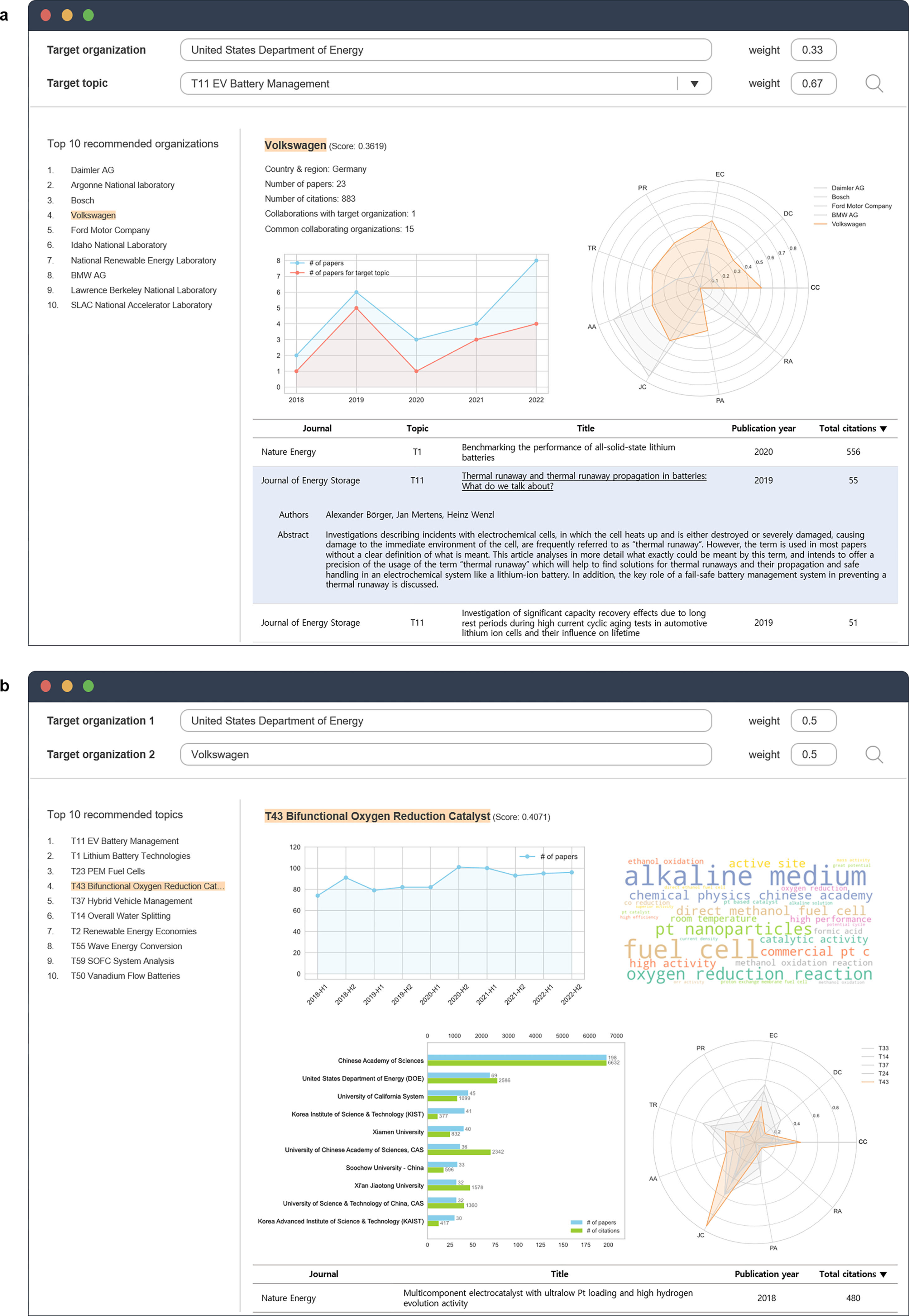

Fig. 8a presents the results of recommending new collaborative organizations based on Period 2 data, where the United States Department of Energy (DOE) and the topic “EV battery management” were set as the user and target topics, respectively. Consequently, various candidates (e.g., “Daimler AG,” “Argnonne national laboratory,” “Bosch,” “Volkswagen,” and “Ford motor company”) were suggested. Given that “Volkswagen,” based in Germany, was selected as one of the candidate organizations, brief information and publication-based statistics were provided. A radar chart comparing network indicators for similar organizations was provided to enable users to assess the centrality of candidates within the open innovation ecosystem and their similarity to the users. The rationale for this recommendation can be understood from these results. Volkswagen collaborated with this user only once in the past but shared 15 common collaboration partners. Research interest in this topic has been increasing since 2020, and its network centralities have been very high compared to those of other candidates. Therefore, Volkswagen can be considered an appropriate partner with sufficient potential and capability for the DOE to collaborate with in EV battery management research.

Implementation of interactive triplet recommendation protocols for energy open innovation. (a) Protocol for recommending new research collaborators. (b) Protocol for recommending new collaboration topics.

Fig. 8b presents a snapshot of recommending new collaboration topics for a user and its collaborating organization, illustrated with case studies from DOE and Volkswagen. Target organizations could select “Bifunctional oxygen reduction catalyst” as a collaborative topic to advance fuel cell technology for electric vehicles (Muthukumar et al., 2021; Pramuanjaroenkij & Kakaç, 2023; Sulaiman et al., 2015). The topic has been consistently studied over the period, with key terms including “alkaline medium,” “fuel cell,” and “oxygen reduction reaction.” The user organization is one of the major organizations after the Chinese Academy of Sciences, indicating its high feasibility for R&D purposes. Network centrality appeared to be moderate compared to other topics, and the similarity between the two target organizations was not very high. However, the Jaccard coefficient was particularly high because of the presence of many common neighboring nodes. Thus, practitioners can identify open innovation opportunities when target organizations or topics are provided, enabling users to directly review and evaluate potential candidates.

DiscussionValidation of the proposed approachNewly developed methods must be deployed with caution because their practical implementation involves numerous critical considerations. We validated the recommendation performance by testing two additional network embedding models (Node2Vec and TransE) using Python libraries (node2vec and PyKEEN). The hyperparameters of each model were determined through a grid search based on the recommendation performance as follows: The Node2Vec model was trained with the embedding dimension set to 128, walk length set to 80, number of walks set to 10, window size set to 10, and p and q set to 1. The TransE model was trained under the stochastic local closed-world assumption, and the embedding dimensions, epochs, and batch sizes were set to 128, 100, and 256, respectively. The performance of our recommendation methods was evaluated using three quantitative metrics: (1) mean average precision (MAP), which evaluates how well the model accurately ranks linked triplets and represents the average precision for each target pair; (2) mean reciprocal rank (MRR), which evaluates how highly a linked triplet appears in the ranking and is the average of the inverse ranks of the first linked triplet for each target pair; (3) the ratio of triplets, which can be calculated by dividing the total scores into equal intervals and calculating the number of triplets linked to each score interval.

Fig. 9a and b illustrates the performance of the first task, partner selection, given a topic of interest. DeepWalk, which is fundamentally based on Word2Vec and is an unsupervised learning technique that explores the structure of a network through random walks, and performs better than Node2Vec or TransE. In particular, the MRR of DeepWalk was 0.4065, which means that, on an average, each target topic-organization pair formed a triplet with the second or third highest value among the recommended organizations. In addition, 76 % and 50 % of the triplets in the two highest score intervals were linked in Period 2. Fig. 9c and d shows the results for the second task, topic recommendation, given a collaborating organization. There was a slight difference between DeepWalk and Node2Vec in terms of MAP and MRR, whereas DeepWalk exhibited a much better performance in terms of the ratio of linked triplets by the score interval. In the highest-scoring interval, the hit rate of DeepWalk was 25 %, which is 2.5 times higher than that of Node2Vec.

Performance evaluation of research collaboration recommendations. (a) Mean average precision (MAP) and mean reciprocal rank (MRR) for Task 1 across different network embedding models. (b) Ratio of linked triplets according to recommendation score intervals for Task 1 analyzed using the network embedding model. (c) MAP and MRR for Task 2 across different network embedding models. (d) Ratio of linked triplets according to recommendation score intervals for Task 2 analyzed using the network embedding model.

Finally, we performed a statistical test to verify whether the proposed approach could effectively identify the linked triplets. We statistically compared the average recommendation scores of the linked and unlinked triplets using the best-performing DeepWalk model. Welch’s t-test was performed by setting all weights to 0.5 and equalizing the sizes of the groups through random sampling. Results show that the proposed recommendation scores for linked triplets were significantly higher than those for the unlinked triplets (Table 1), indicating that the proposed approach can effectively distinguish collaboration opportunities.

Results of Welch’s t-test for the difference in the average recommendation scores of the triplets.

| Test | Group | N | Mean | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task 1 | Linked | 85,014 | 0.240 | 0.112 | 299.386 | < 0.001 |

| Not linked | 85,014 | 0.142 | 0.057 | |||

| Task 2 | Linked | 85,014 | 0.169 | 0.065 | 152.916 | < 0.001 |

| Not linked | 85,014 | 0.124 | 0.056 |

Note: As the sizes of the linked and non-linked groups were different, the non-linked triplets were randomly sampled to match the sample sizes of the two groups. The homogeneity of variances was not satisfied, based on Levene’s test (Task 1: F = 19,477.951, p < 0.001; Task 2: F = 1209.976, p < 0.001).

The proposed approach offers a comprehensive understanding of energy open innovation ecosystems with significant implications for theory, practice, and policy. From an academic perspective, this study contributes to the open innovation literature, particularly in the energy sector. The proposed approach implements the theoretical concept or framework of open innovation systems as a large-scale network based on extensive literature data. This network can flexibly respond to data updates and changes depending on the analytical context. Previous studies have been constrained by their reliance on homogeneous networks composed of a single type of entity (e.g., co-authorship or co-patenting), limiting their ability to account for diverse elements of the open innovation ecosystem. In contrast, this study constructs a heterogeneous network that integrates multiple entity types, including topics, papers, organizations, and nations, enabling a more comprehensive analysis. This approach facilitated a nuanced examination of ecosystem trends and the generation of evidence-based recommendations for collaboration partners and future research directions. To this end, we propose a triplet structure to represent open innovation relationships between organizations and utilize network embedding techniques to consider the context of the global and local structures of large-scale networks. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to adopt network embedding (one of the latest graph neural network models) to effectively analyze the open innovation ecosystem. Second, the integrated use of energy-specific PLM and unsupervised learning facilitates the understanding of detailed research topics in the energy field compared with previous studies that utilized keyword-based co-occurrence and probabilistic modeling techniques. The proposed approach defines subfields in an energy-specific and interpretable manner and provides recent trends and characteristics for the identified research fields with quantitative information. Finally, the proposed approach was designed to be reproducible and systematic, allowing for flexible adaptation in other studies. Although this study focused on identifying detailed research topics and organizations for open innovation ecosystem landscaping, other elements representing regulation, society, and the environment can be added to the current network to enable a more realistic representation of innovation ecosystems as digital twins. In terms of its application to theoretical models, the proposed approach can be further developed as a tool to represent various theoretical models of innovation ecosystems. Specifically, it can express the national innovation system by recommending inter- and intra-national collaboration, the triple-helix model by incorporating information on organization types (e.g., universities, industries, and governments), and the sectoral innovation system by analyzing data from various fields. In addition, the proposed approach can be used to investigate the backbone of knowledge flow in innovation ecosystems by analyzing knowledge diffusion networks using citation and co-authorship data.

Practically, the proposed approach can be developed into automated software that can assist experts who lack knowledge of machine learning, such as language modeling or unsupervised learning, in analyzing an open innovation ecosystem. This software, designed to identify potential open innovation opportunities, can be further developed into a web-based platform that recommends collaboration opportunities based on user-inputted organizations or research topics of interest, as illustrated in a case study. The software can generate immediate results upon constructing the open innovation network, although training network-embedding models requires approximately 1–2 h using graphical processing units (e.g., NVIDIA Tesla T4). Additional maintenance tasks include periodically updating the network and embedding models to reflect newly introduced nodes, such as papers, organizations and nations. For example, when a new organization publishes a paper, the research topic of this study can be inferred through a pre-trained topic detection model, its related existing nodes (e.g., collaborating organizations) are connected to update networks, and the network embedding model is retrained. Thus, the proposed approach and its software are expected to be useful as complementary tools to support experts’ decision-making related to open energy innovation, especially in nations and organizations with limited energy resources.

From a political perspective, it is important to support R&D in energy resources and transition because the energy industry play key role in a nation’s sustainable industrial development, economic growth, and environmental conservation. For example, the Republic of Korea is showing growing national interest in the energy field by expanding investment in energy research policies to approximately $64.6 billion by 2025. Among various reports on technological innovation in the energy field, there is a consensus that integrating new ideas, technologies, and solutions from multiple organizations or nations is more critical than relying on a single entity. Although prior studies have helped establish the direction of policymaking by introducing the theory and concepts of open innovation (e.g., national and sectoral innovation systems and the triple helix model), they had limitations in developing energy-specific ecosystems and exploring potential opportunities for open innovation. The Republic of Korea has established various national projects regarding energy R&D; however, these policies focus on energy resource transmission and storage technologies that can contribute to domestic industries through the national triple helix model rather than undertaking the challenging R&D development of new renewable energy resources through international collaboration. Considering the global nature of energy challenges, the development of an intelligent platform that utilizes big data to comprehensively identify collaborative opportunities and enhance innovation capabilities is critical. Accordingly, the findings and benefits of the proposed approach are expected to advance the analysis of the open innovation ecosystem in the energy field, thereby contributing to the promotion of national, organizational, and sectoral innovation.

ConclusionThis study proposes NEON based on large-scale network modeling and embedding to effectively navigate and analyze the energy open innovation ecosystem. Our case study, which included 149 nations, 6104 organizations, 88,727 papers, and 63 topics, demonstrated that the proposed approach would serve as a useful and effective complementary tool for advancing open energy innovation in the era of information proliferation. This study makes two contributions. First, from an academic perspective, this study promotes the adoption of open innovation concepts in the energy field by systematically and reproducibly developing open innovation ecosystems. The integration of PLMs and density-based clustering enables the identification of numerous subfields within the energy domain, overcoming the challenges of traditionally constrained sector analyses in the open innovation literature. The open innovation ecosystem implemented through large-scale network modeling and embedding techniques enables a quantitative analysis of the relationships among nations, organizations, and research topics, offering deeper insights into their relationships and relevance. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to adopt network embedding in the field of open innovation ecosystems. Although the primary focus is on identifying potential collaborative opportunities for global open innovation, the proposed approach can be expanded for other purposes. Second, from a practical perspective, web-based protocols were developed to automate the functions of the proposed approach, benefiting those who are unfamiliar with natural language processing techniques and machine learning models. The proposed approach and its software system are expected to be useful complementary tools for supporting expert decision-making, particularly for organizations with limited energy resources exploring potential collaboration partners or new R&D solutions. Organizational managers and policymakers can utilize the software to systematically monitor trends in open energy innovation ecosystems, identify the key research priorities of major nations (e.g., Mission Innovation participants), and explore potential collaboration opportunities for open innovation. These insights can inform the development of global R&D policies, such as joint research initiatives, international funding programs, and technology transfer agreements, thereby fostering knowledge sharing and cooperation on a global scale.

However, this study had some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, additional node information related to an energy open innovation ecosystem can be incorporated. For example, disambiguated data on individual researchers can be obtained through natural language processing analysis of name and affiliation history database (Milojević, 2013). With such datasets, it would be possible to analyze open innovation activities at the research group or individual researcher levels (Choi et al., 2023; Chung et al., 2021a). Similarly, new types of links, such as citations, which indicate the academic impact of papers on subsequent research, can be added (Weis & Jacobson, 2021). Second, entities representing scientific knowledge, such as materials, properties, and characterization methods, can be incorporated into energy-specific knowledge graphs (Choi & Lee, 2024a; Gao et al., 2023; Trewartha et al., 2022). This process requires the extraction and standardization of these entities, which can be achieved using named entity recognition and normalization models tailored to the energy sector (Weston et al., 2019). Third, developing a new network embedding method tailored to our open innovation network would be beneficial for effectively analyzing the meta-paths between heterogeneous entities and triplets. Finally, because our approach has been applied to the energy sector, case studies in other domains should be conducted to validate the feasibility of the NEON. Fourth, future studies should employ more rigorous scientific methods for parameter selection (e.g., Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning, or evolutionary algorithms). Finally, to apply this protocol to other domains (i.e., non-energy fields), it is essential to test various PLMs or fine-tune the PLM with domain-specific documents to better capture the specialized context of the target field (Choi et al., 2025). Considering the rapidly evolving nature of technological content over time, it is important to periodically update PLMs. Furthermore, to identify and address potential dataset bias, it is necessary to incorporate and compare heterogeneous data sources, including other academic databases such as Scopus and patent data.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJaemin Chung: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Janghyeok Yoon: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Jaewoong Choi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A2C1010027) and the Human Resources Program in Energy Technology of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20204010600220).

Several string-comparison algorithms were tested to link the WoS and GRID datasets. We matched organization names in the WoS dataset to GRID using three algorithms: Jaccard similarity (JS), Levenshtein distance (LD), and Jaro-Winkler similarity (JWS). We randomly selected 100 samples of organizational names from the WoS dataset and manually checked the accuracy of the matching results. The JS algorithm successfully matched 90 organizations, whereas the LD and JWS algorithms matched 83 and 44 organizations, respectively.

We take a closer look at the results for JS and LD, which are algorithms with high matching accuracy. JS checks only for the presence of characters in two given strings. In contrast, LD calculates the distance based on the number of character edits; therefore, it becomes unnecessarily sensitive when the positions of words are changed or when additional words are included. The following are representative cases where JS matched correctly but LD did not: For the WoS organization name “National Institutes of Health (NIH) - USA,” JS matched “National Institutes of Health,” while LD matched “National Institutes of Health Sciences.” For the WoS organization name “Grundfos,” JS matched “Grundfos (Denmark),” while LD matched “Kudos.” For the WoS organization name “Irkutsk National Research Technical University,” JS matched “National Research Irkutsk State Technical University,” while LD matched “Lutsk National Technical University.” For the WoS organization name “National Research & Development Institute Optoelectronics INOE 2000,” JS matched “National Institute for Research and Development in Optoelectronics,” while LD matched “National Research & Development Institute for Textiles and Leather.” There were no sample cases in which LD matched but JS matched.

In an energy open innovation network, a node representing an organization or nation with high centrality indicates active research activity, whereas a topic with high centrality suggests significant attention at the national or organizational level. Moreover, the high similarity between the two organizations indicates that they conduct research in closely related scientific fields. Similarly, a high similarity between an organization and a specific topic suggests that the organization is highly relevant to that topic, thereby enhancing the feasibility of related R&D activities.

We employed five network centrality indicators to evaluate the importance of a node with respect to the structure of the entire network and the flow of information using slightly different formulas. The clustering coefficient (CC) indicates the connection density around a node and measures the regional density of a node and its neighbors (Watts & Strogatz, 1998). Degree centrality (DC) indicates the number of connected neighboring nodes and the direct influence of a node (Dong & Yang, 2016). Eigenvector centrality (EC) evaluates the influence of a node by considering the importance of connected neighbors; nodes connected to important nodes receive higher scores (Aaldering et al., 2019). PageRank (PR) centrality is calculated based on the count and importance of referencing nodes (Yan & Ding, 2011). Triangle (TR) centrality counts the number of triangular structures in which a node is included, indicating the importance of a node in the local structure (Burkhardt, 2024). In addition, we used four network similarity indicators to determine the similarity of the characteristics or locations shared by two nodes in the network (Choi et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2020). The Adamic-Adar (AA) indicator assigns similarity by weighing the importance of common neighbors and assigning higher weights to rarer common neighbors. The Jaccard coefficient (JC) indicator is a simple and intuitive indicator that calculates the common neighbor ratio of two nodes. In the preferential attachment (PA) indicator, the connectivity of a node is affected by the number of local connections, reflecting the tendency of large hub nodes to have more connections. The resource allocation (RA) indicator evaluates similarity based on the ability to distribute resources through common neighbors.

Labels, abbreviations, and key phrases for energy research topics. Key phrases for each topic were extracted using spaCy, a Python natural language processing library. We provided Claude 3.5 Sonnet with key noun phrases and key document titles for each topic to generate topic labels and abbreviations and finally reviewed the generated results.

Equations for network indicators were used to evaluate the recommended candidates. Here, uand vare nodes, and Γ(u) represents the set of neighbor nodes of u.