In the current unpredictable business landscape, organisational resilience is essential for firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to navigate crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the typically limited resources of SMEs, this study sheds light on how knowledge-based factors and dynamic capabilities—such as knowledge-oriented leadership, absorptive capacity, and innovation quality—can be strategically managed to bolster organisational resilience in SMEs. Adopting a knowledge-based view and the dynamic capability theory, the study emphasises the significance of absorptive capacity and knowledge-oriented leadership in fostering innovation quality, which, in turn, enhances organisational resilience capabilities. Data from 213 Thai SMEs reveal that while absorptive capacity does not directly impact resilience capabilities, its effect is mediated by innovation quality, highlighting the necessity of high-quality innovation for effective crisis management. Knowledge-oriented leadership significantly influences coping and adaptation capabilities, with innovation quality completely mediating the relationship between knowledge-oriented leadership and anticipation capability. Furthermore, organisational unlearning enhances the impact of knowledge-oriented leadership on adaptation capability, underscoring the importance of discarding obsolete knowledge for resilience. The study also identifies competitive intensity as a moderator between absorptive capacity and anticipation capability, suggesting that SMEs in competitive industries utilise external knowledge better for resilience.

The current business environment is filled with uncertainties and unexpected threats, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. A solution to survive and thrive in this dynamic and turbulent environment is to enhance the organisational resilience of a firm (Duchek, 2020; Hamel & Välikangas, 2003). Organisational resilience can be especially important for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which generally have fewer resources than large enterprises to deal with serious problems such as crises (Eggers, 2020). Considering the knowledge-based economy of the modern era, where information and expertise are pivotal for business operation, this study adopts a knowledge-based view (KBV) and the dynamic capability theory to investigate how SMEs can leverage their knowledge resources to build resilience in a dynamic business environment.

Numerous lockdown measures imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021 led to a downturn in the global economy. Thailand, a country with a developing economy, relatively well contained the coronavirus in the initial phase of the pandemic (Lee, 2020). However, the country still experienced significant repercussions. After facing five waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s economy seems to have recovered (Arunmas et al., 2022). Thus, Thailand’s COVID-19 pandemic experience is deemed to be a good context to study organisational resilience capabilities based on the different stages of a crisis timeline.

According to Duchek (2020), organisational resilience is a meta-capability that comprises a set of organisational capabilities that allow for successfully achieving three resilience stages based on the crisis timeline, that is, before, during, and after a crisis. In other words, organisations need to possess three resilience capabilities—anticipation, coping, and adaptation capabilities—to survive and thrive through a crisis (Duchek, 2020; Duchek et al., 2020).

Scholars have underscored the importance of effective information sharing, knowledge management, and learning processes in developing organisational resilience capabilities (Duchek, 2020; Evenseth et al., 2022; Mafabi et al., 2012). Although many scholars have studied organisational resilience, the exact way to systematically achieve organisational resilience in real settings remains unknown (Duchek, 2020; Kantabutra & Ketprapakorn, 2021). Considering the knowledge-based economy of the modern era, where information and expertise are pivotal for business operation, this study adopts a KBV and the dynamic capability theory to investigate how SMEs can leverage their knowledge resources to build resilience in a dynamic business environment.

Hillmann and Guenther (2021) identified absorptive capacity (ACAP) as a protective factor linked to organisational resilience, though several scholars argue that the two concepts overlap and that their relationship requires clearer articulation (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014). Meanwhile, knowledge-oriented leadership (KOL) has gained increasing attention as a distinct leadership style (Banmairuroy et al., 2022; Rehman & Iqbal, 2020), yet few studies have examined its connection to organisational resilience. Ayoko (2021) also emphasised the need to explore how different leadership styles influence resilience, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the field of organisational unlearning (OU) remains underdeveloped, with Orth and Schuldis (2020) and Evenseth et al. (2022) calling for more empirical research on its role in learning and resilience.

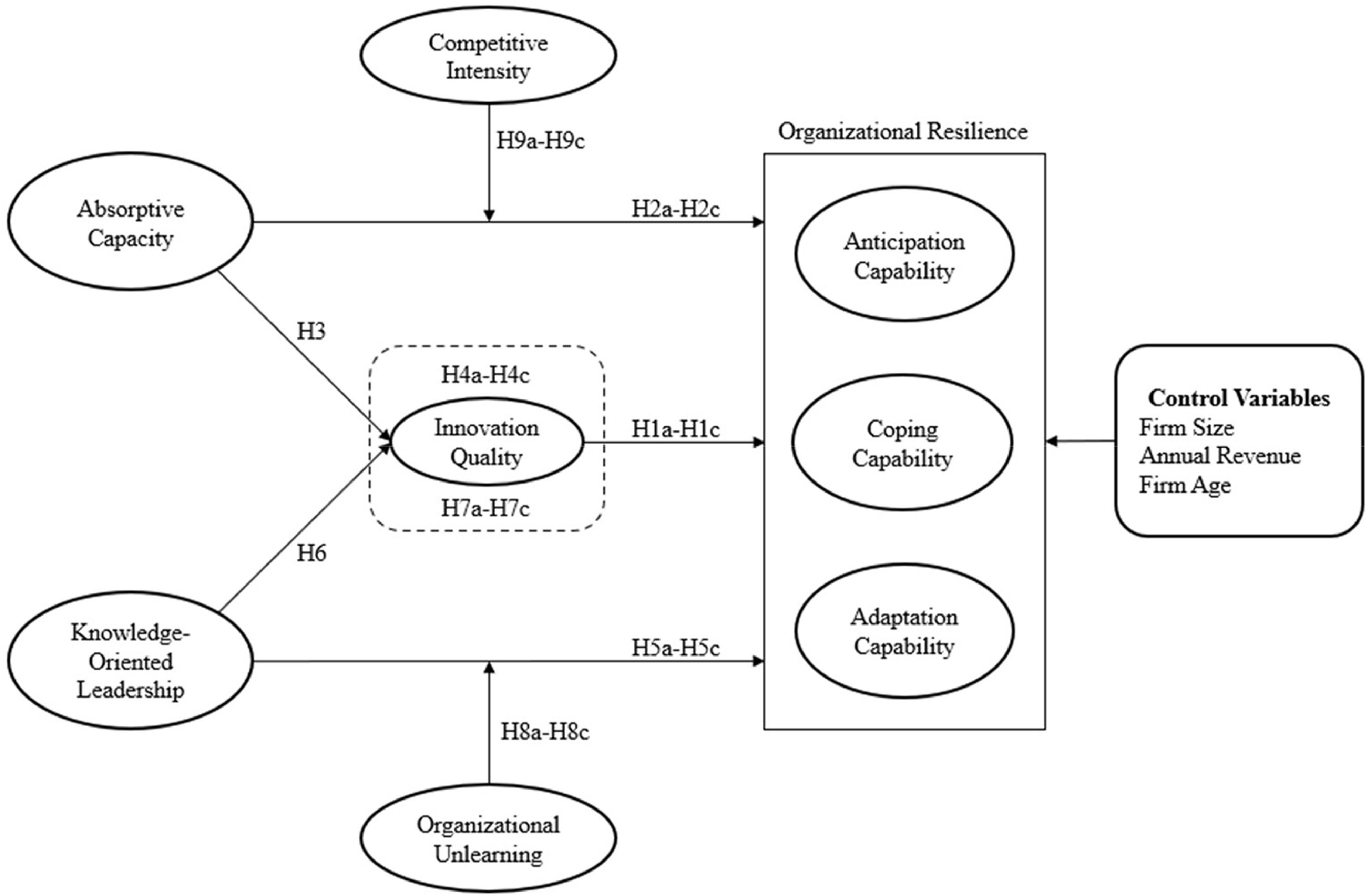

Therefore, this study focuses on the contribution of knowledge-based factors and capabilities—such as innovation quality (INQ), ACAP, and KOL—to the development of resilience capabilities in SMEs. Additionally, the study examines how OU ability and competitive intensity (CI) in the industry serve as moderating factors, as both can influence how effectively SMEs leverage their knowledge-based capabilities to build resilience. Thereby, this study investigates the relationship between INQ, ACAP, KOL, OU, CI, and organisational resilience capabilities in the context of Thai SMEs based on the COVID-19 pandemic.

The remainder of the paper is structured into five key sections: a review of the relevant literature, research methodology, presentation of the results, discussion of the findings, and conclusion.

Literature reviewThe COVID-19 pandemic and SMEs in ThailandThe COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on SMEs in Thailand. As a response, the Thai government prioritised strategies and guidelines aimed at enhancing the capacity of SMEs to survive, recover from the crisis, and achieve sustainable long-term growth (Office of Small and Medium Enterprise Promotion [OSMEP], 2021). Government-imposed disease control measures, such as the closure of entertainment venues, enforcement of social distancing, and localised lockdowns, led to the suspension or even permanent closure of many businesses. The situation worsened significantly during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, when the economic conditions for SMEs reached their lowest point (OSMEP, 2021).

Globally, SMEs are recognised as critical drivers of economic development. In Thailand, their economic contribution declined notably during the pandemic. In 2020, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contribution from SMEs dropped to 34.2%, and their expansion rate contracted by 9.1% compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019 (OSMEP, 2021). Nevertheless, by 2024, SMEs accounted for 35.2% of Thailand’s national GDP (OSMEP, 2024) and represented approximately 99.5% (3,272,478 firms) of all registered enterprises in the country (SME Big Data, 2024), as shown in Fig. 1. These figures suggest that the overall contribution of SMEs to GDP has rebounded since the pandemic. However, a closer examination of the GDP distribution by enterprise size reveals a decline in the share of micro and small enterprises, while the share held by medium-sized enterprises has increased (OSMEP, 2024). This indicates that recovery has been uneven, with many smaller and vulnerable firms still struggling to recover.

Compared to large organisations and well-established multinational corporations, most Thai SMEs face several challenges in general (e.g., limited access to skilled human resources, capital, and knowledge crucial for innovating and expanding their businesses). These limitations hinder their ability to expand and adapt during a crisis. Therefore, understanding how SMEs can build organisational resilience despite constrained resources is essential for ensuring their long-term survival. Additionally, the Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) launched a new five-year investment promotion strategy for 2023–2027 to promote investment and restructure the country’s economy (Bangkok Post, 2022). One of its primary purposes is to strengthen SMEs and start-ups by ensuring they are linked to the global market and supply chain. Due to these developments, it is timely and critical to investigate the factors that influence resilience capabilities in Thai SMEs before, during, and after the pandemic.

Organisational resilienceHome III and Orr (1997) explained resilience as a basic quality of a firm that responds productively to disruptions without lingering in long regressive behaviour. Coping with the disruption is essential for organisations to survive when facing uncertainties. However, firms sometimes need to advance, adjust, or change the existing structure (metamorphose) for a better fit in new environments (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). Hence, Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) argued that an organisation’s positive adjustments resulted from challenges deemed to make the organisation more robust and resourceful, which in turn help the organisation become resilient. Ortiz‐de‐Mandojana and Bansal (2016) described organisational resilience as an incremental capacity to anticipate and adjust to circumstances. Considering the active response and anticipation perspectives, Duchek (2020) provides an explicit definition of organisational resilience: ‘the ability to anticipate potential threats, to cope effectively with adverse events, and to adapt to changing conditions’ (p. 220). In this study, the scholar follows Duchek’s (2020) resilience definition.

The knowledge-based view for fostering SMEs’ organisational resilienceThe KBV is derived from the resource-based view (RBV). RBV explains that the radical sources and drivers of organisations’ competitive advantages and superior performances are related to the attributes of organisations’ resources and capabilities, which are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable (Barney, 1991). Under KBV, knowledge is regarded as the most important strategic resource, which implies creating and sustaining competitive advantages and implementing strategies in organisational structure and systems (Grant, 2015). Existing studies on KBV contended that firms’ success, competitiveness, and long-term survival in challenging business environments mainly rely on firms’ knowledge-based resources (Donate & De Pablo, 2015; Valaei et al., 2017).

Globally, the paradigms for attaining firms’ productivity change with the age of emerging technologies. The transition from manufacturing to services in many developed economies relies on manipulating information and knowledge, not on the application of physical products (Fulk & DeSanctis, 1995). Unlike other tangible resources, knowledge can be used concurrently in different applications without its value diminishing (Wilcox King & Zeithaml, 2003). Thus, KBV becomes an imperative theory for most modern organisations.

KBV is deemed to be an important perspective for SMEs, as they often have limited financial resources compared to large enterprises. KBV emphasises that knowledge and intellectual capital, such as expertise, experience, and innovative ideas, are crucial resources for firms. Considering this perspective, SMEs may have better chances to compete effectively in the market by leveraging their unique knowledge rather than just financial capital.

The dynamic capability perspective for fostering SMEs’ organisational resilienceTeece et al. (1997) developed dynamic capability theory to explain how firms can compete and survive in dynamic business environments with rapid changes. This concept was also rooted in RBV (Barney, 1991). RBV argued that businesses need to have intangible and tangible assets that are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate or substitute for competing successfully. However, in a highly dynamic environment, firms’ resources alone are deemed insufficient (Teece et al., 1997). Teece et al. (1997) thus argued that ambitious firms might require the ability to redeploy resources and respond to threats quickly. The scholars defined dynamic capability as an organisation’s ability to combine, construct, and reconfigure external and internal organisational competencies to respond to a turbulent environment. According to Rugami and Evans (2013), dynamic capabilities are assumed to create the flexibility of an organisation to exploit its resources effectively to achieve harmony with its peculiar business environment.

The dynamic capability theory is also highly relevant for SMEs, particularly in the current rapidly changing business environment. SMEs often face a dynamic and unpredictable market environment, including shifts in technology, customer preferences, regulations, and competition. Dynamic capabilities allow SMEs to be more flexible and responsive. By developing and leveraging their ability to sense opportunities and threats, seize them, and reconfigure their resources accordingly, SMEs can navigate these changes effectively. While large firms may have vast resources, SMEs often face significant constraints in terms of financial, human, and technological resources. The dynamic capability theory provides a framework that helps SMEs to maximise the value of their limited resources by focusing on the capabilities they can build, rather than relying on having large quantities of resources.

Drawing on the KBV and the dynamic capabilities perspective, this study emphasises knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and factors—specifically INQ, ACAP, KOL, OU, and CI—as critical factors for enhancing organisational resilience.

Innovation quality (INQ)Innovation typically associates with creativity and non-conformity, while quality relates to standardisation, low error tolerance, and systematic procedures (Wang & Wang, 2012). Therefore, INQ pertains to the degree to which new products or services fulfil customer needs and expectations (Lanjouw & Schankerman, 2004; Taherparvar et al., 2014). According to Haner (2002), INQ can be evaluated at three levels: product or service, process, and firm. Hence, this study adopts the definition of Haner (2002), Taherparvar et al. (2014), and Wang and Wang (2012), viewing INQ as the cumulative innovation performance at all levels within an organisation.

Relationship between innovation quality and organisational resilienceVarious studies have shown that different innovations positively contribute to fostering organisational resilience. For example, Ahn et al. (2018) demonstrated that during crises, open and closed innovation help organisations achieve resilience based on UK panel data. Senbeto and Hon (2020) confirmed that employees’ innovative abilities are crucial during crises in their study. Vakilzadeh and Haase (2021) underscored innovation and business models as essential for anticipation and coping capabilities in organisational resilience. While innovation is beneficial for fostering organisational resilience, mere innovation might not be sufficient. Effective organisational resilience is best predicted through high INQ, characterised by standardisation, low error tolerance, and systematic procedures. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 An organisation’s innovation quality positively affects fostering (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

ACAP was first introduced by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) as a firm’s ability to recognise the value of external knowledge and assimilate and exploit it for commercial gain. These scholars also emphasised firms’ research and development (R&D) as a driver of ACAP. Lane and Lubatkin (1998) conceptualised the construct as relative ACAP, which is the ability of a (student or receiver) organisation to value, assimilate, and apply knowledge derived from another (teacher or sender) organisation. In 2002, Zahra and George (2002) reviewed the concept of ACAP and redefined it as a dynamic capability. According to the new definition, ACAP is a set of organisational routines and processes by which firms acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge to generate a dynamic organisational capability. For this study, the scholar considers ACAP as a type of dynamic capability and follows the ACAP definition of Zahra and George (2002).

Relationship between absorptive capacity and organisational resilienceSince dynamic capabilities have been considered important factors for promoting organisational resilience in several papers (Akpan et al., 2021; Martinelli et al., 2018), ACAP, as a knowledge-based dynamic capability, is also expected to reinforce efforts in building organisational resilience capabilities. Many studies from the supply chain management literature have highlighted the relationship between ACAP and an organisation’s supply chain or operational resilience. For example, Roh et al. (2021) analysed data from 205 managers and practitioners from different firms to study the influence of ACAP on low/high-impact resilience in organisations’ supply chains. Considering ACAP as a boundary-spanning capability, Gölgeci and Kuivalainen (2020) found a direct positive effect of ACAP on supply chain resilience and the partial mediation effect of ACAP on the relationship between social capital and supply chain resilience by studying 265 Turkish firms. Therefore, ACAP evidently influences the resilience of organisations, and the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2 An organisation’s absorptive capacity positively affects fostering (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

ACAP is crucial for fostering innovation and enhancing a firm’s competitive advantage (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Lichtenthaler (2009) found that firms with high ACAP exhibited greater innovation performance, measured by the quality and impact of their innovations. Similarly, Kostopoulos et al. (2011) demonstrated that ACAP positively influenced INQ through improved knowledge integration and application processes. Firms with high ACAP are better positioned to achieve high IQ. These firms are more proficient in managing their R&D processes, resulting in efficient and higher-quality innovation outcomes (Grimpe & Sofka, 2009). Moreover, Jia et al. (2024) highlighted that organisations with a high level of ACAP are more capable of utilising internally generated and shared knowledge, which enhances innovation, boosts efficiency, and improves overall performance. Hernández-Perlines et al. (2024) noted that firms possessing strong ACAP are effective at identifying valuable external knowledge, integrating it within their internal environment, and utilising it to drive innovation, as demonstrated in their study on family firms’ innovative capacity. Thus, the researcher proposed the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 An organisation’s absorptive capacity positively affects its innovation quality.

High ACAP allows firms to manage and utilise external knowledge effectively, leading to higher INQ, which includes superior performance in product development, process improvements, and service enhancements (Grimpe & Sofka, 2009; Zahra & George, 2002). Innovation helps organisations better manage disruptions and recover from adverse events (Ahn et al., 2018; Senbeto & Hon, 2020). Firms with high ACAP are likely to achieve higher INQ, which in turn fosters greater organisational resilience. Lichtenthaler (2009) and Kostopoulos et al. (2011) found that ACAP positively influences innovation performance through improved knowledge integration and application processes. This study therefore proposes that INQ mediates the relationship between ACAP and organisational resilience capabilities. The following hypothesis is posited.

Hypothesis 4 An organisation’s innovation quality mediates the relationship between absorptive capacity and organisational resilience capabilities: (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

Several studies have agreed that KOL is the manifestation of transformational and transactional leadership, along with motivational and communication factors, for facilitating better knowledge management that influences innovation in organisations (Donate & De Pablo, 2015; Donate et al., 2022; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018; Rehman & Iqbal, 2020). Transactional leadership is best used to institutionalise, reinforce, and refine existing knowledge, while transformational leadership is best used to challenge the firm’s current situation (Baškarada et al., 2017; Jansen et al., 2009). KOL is often explained as how the management level shows an attitude, mindset, or action that encourages the activities of knowledge generation, distribution, and exploitation in an organisation (Mabey et al., 2012; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018). Thus, in this study, the scholar defines KOL as an attitude or action that engenders new knowledge creation, sharing, and utilisation, which may affect rational and collective outcomes by communicating, inspiring, rewarding, and motivating (Donate & De Pablo, 2015; Donate et al., 2022; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018).

Relationship between knowledge-oriented leadership and organisational resilienceAs different leadership styles and behaviours of organisations have affected the cultivation of organisational resilience (Odeh et al., 2021; Waldman et al., 2001), KOL, as a combinative leadership style of transformational and transactional leadership, is also expected to influence organisations’ resiliency. According to Hamel and Prahalad (1994), leaders who seek to cultivate organisational resilience establish explorations for external forces that may impact their organisations’ future success. With KOL, a leader could enable the members of an organisation to effectively handle the knowledge acquired from external sources. Organisational resilience capabilities require a range of learning processes for different resilience stages (Evenseth et al., 2022). Knowledge-oriented leaders facilitate those learning processes by inspiring, rewarding, motivating, and communicating with the members of organisations. In this respect, KOL is posited to influence the firm’s organisational resilience. Therefore, the author offers the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5 An organisation’s knowledge-oriented leadership positively affects fostering (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

According to Donate and Sánchez de Pablo (2015), KOL is vital for fostering innovation performance through effective knowledge management. In a study in France, Naqshbandi and Jasimuddin (2018) demonstrated that KOL positively impacts open innovation. Sadeghi and Rad (2018) found significant effects of KOL on innovation performance, while Zia (2020) confirmed KOL’s positive impact on project-based innovation performance in SMEs from Pakistan. In an empirical study regarding KOL, knowledge management behaviour, and innovation performance in the context of project-based work in Pakistan, Zia (2020) found that KOL positively affects project-based innovation performance. Similarly, Chaithanapat et al. (2022)’s study of 283 SMEs in Thailand also found that KOL in SMEs positively influences the INQ of the firms. From these studies, the researcher proposes the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6 An organisation’s knowledge-oriented leadership positively affects its innovation quality.

KOL combines transformational and transactional leadership styles, emphasising communication and motivational skills to enhance knowledge management and innovation performance within the organisation (Donate & de Pablo, 2015; Ribière & Sitar, 2003). Furthermore, KOL enables organisations to adapt to changes and respond to crises effectively by promoting an environment where knowledge generation, allocation, and exploitation are prioritised (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018; Zahra & George, 2002). Empirical studies support the positive impact of KOL on INQ, as discussed in the previous section. When organisations exhibit high IQ, they are more likely to be equipped to anticipate, cope with, and adapt to external challenges and threats. INQ, driven by effective KOL, may enhance the organisation’s ability to detect potential threats and effectively manage acquired knowledge, thereby strengthening its resilience capabilities. Therefore, the researcher proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 7 An organisation’s innovation quality (INQ mediates the relationship between knowledge-oriented leadership and organisational resilience capabilities: (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

Tsang and Zahra (2008) defined OU as abolishing old routines in favour of new ones. According to Hedberg (1981), as reality changes, knowledge expands and simultaneously becomes obsolete; thus, acquiring new knowledge and removing obsolete ones are essential for better understanding. Morais-Storz and Nguyen (2017) explained that unlearning capability, along with learning, is crucial for making an organisation strategically resilient. Fiol and O’Connor (2017) offered a more explicit unlearning definition, which is ‘intentional displacement of well-established patterns of action and understanding due to an exogenous disruption’ (Fiol & O’Connor, 2017, p. 6). The scholars claimed that unlearning is deemed to help to learn better and vice versa. This study defines unlearning as a firm’s ability to intentionally remove obsolete knowledge in favour of new one (Tsang & Zahra, 2008).

Moderating role of organizational unlearning on the relationship of knowledge-oriented leadership and organisational resilienceTsang and Zahra (2008) explained that the unlearning ability of an organisation is often seen as a necessary condition for successful adaptation to external changes, encouraging organisational learning and improving the firm’s performance. Additionally, several studies have underlined the importance of a firm’s unlearning ability for building a resilient organisation (Morais-Storz & Nguyen, 2017; Orth & Schuldis, 2020; Wang, 2008). According to Becker (2008), the unlearning ability is a key factor for successfully competing in dynamic and complex markets, as it could provide the constant development of newness. Dayan et al. (2024) emphasised that unlearning is essential because the established routines and cognitive models that previously contributed to an organisation’s success can become inflexible over time, making it difficult to adapt. This inflexibility hinders the organisation’s ability to embrace new knowledge and innovation (Zaidi, 2023). Therefore, the effect of KOL on fostering organisational resilience capabilities is expected to be higher in firms with better unlearning ability. Based on this discussion, the author proposes the following statements.

Hypothesis 8 Higher level of unlearning ability increases the influence of knowledge-oriented leadership on organisational resilience capabilities: (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

CI refers to the degree of competition firms face within an industry. According to Jaworski and Kohli (1993), CI arises when firms encounter significant competition in their industry. It can be characterised by the extent to which rivals impact a company’s focused activities (Ahn et al., 2018; Barnett, 1997). Anning-Dorson (2016) describes CI as rivalry among business units, promotional wars, competitive actions, and various market offers. In the current market, firms frequently face high levels of competition, leading to increased uncertainty. For this study, CI refers to the degree of competition faced by firms in terms of cutthroat competition, promotional wars, price competition, and competitive moves (Anning-Dorson, 2016; Grewal & Tansuhaj, 2001; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993).

Moderating role of competitive intensity on the relationship of absorptive capacity and organisational resilienceAs competition intensifies, organisations must innovate their products and processes to remain competitive (Jones & Linderman, 2014). The outcomes of organisational actions increasingly depend on external factors such as product innovation and competitor activities (Wilden et al., 2013). Higher levels of competitive rivalry drive firms to reconfigure their resource bases to meet future market demands (Barnett, 1997). In such an environment, managers are encouraged to build strong linkages with external partners to develop a comprehensive understanding of available information, enhancing their firms’ adaptability and responsiveness (Alexiev et al., 2016). Moreover, Otache (2024) suggests that intense market competition can encourage SMEs to enhance their innovation capabilities, which subsequently contributes to improved organisational performance. Consequently, it is expected that the impact of ACAP on fostering organisational resilience capabilities will be more pronounced in firms operating in highly competitive industries. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 9 A higher level of competitive intensity increases the influence of absorptive capacity on organizational resilience capabilities: (a) anticipation capability, (b) coping capability, and (c) adaptation capability.

The conceptual model of this research is shown in Fig. 2.

MethodologySampleThe target population of this research is SMEs in Thailand. Thus, the samples were collected from SMEs registered in the Department of Business Development (DBD) DataWarehouse+, an online platform developed by Thailand’s Ministry of Commerce (DBD, 2022). Additionally, this research adopted the SME definition provided by the OSMEP, a Thai government agency (OSMEP, 2020). Table 1 shows the categories of micro, small, and medium enterprises defined by OSMEP (2020).

Definition of SMEs.

Note: The currency is converted to USD using an exchange rate of 1 USD = 32 Thai Baht for the annual revenue .

Source: Office of Small and Medium Enterprise Promotion [OSMEP], (2020).

To calculate the minimum sample size for this study, the researcher followed the power analysis method of Cohen (1992). The researcher needed to collect 156 observations to achieve a statistical power of 80% for detecting R2 values of at least 0.10 (with a 5% probability of error). However, considering the complexity of the research model, the researcher aimed to obtain more samples than the minimum requirement to hedge against the threat of data inadequacy in partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) (Ringle et al., 2012).

Questionnaire developmentThe existing measures were adapted from the literature to create the first draft of the questionnaire. The questionnaire items were then translated into Thai by a professional translator. Three native field experts validated the Thai version of the questionnaire. After revising the questionnaire based on their feedback, it was submitted to the ethical committee of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for ethical review.

The questionnaire consisted of seven main parts. The first part covered respondents’ demographic information. The second part included 10 items related to ACAP, adapted from Pavlou and El Sawy (2006). The third part contained eight items on KOL, adapted and developed from Donate and De Pablo (2015) and Chaithanapat et al. (2022). The fourth part comprised four items addressing INQ, adapted from Taherparvar et al. (2014) and Wang and Wang (2012). The fifth part featured five items reflecting OU, adapted from Lyu et al. (2022). The sixth part included four items on CI, adapted from Grewal and Tansuhaj (2001). The final part focused on organisational resilience capabilities, including six items for anticipation capability (AC), adapted from Rai et al. (2021) and Duchek (2020); four items for coping capability (CC), adapted and developed from Duchek (2020) and Shaya et al. (2022); and four items for anticipation capability (ADC), adapted and developed from Duchek (2020) and Ma and Zhang (2022). All the items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale in a positive direction. An interval scale from 1 point (strongly disagree) to 7 points (strongly agree) was used to measure all constructs.

The traits of the firm, such as firm age, annual revenue, and firm size, were used as control variables. After receiving IRB approval, the researcher conducted a pilot test with 30 samples. The pilot test results also demonstrated reliability and validity, meeting all the requirements for statistical analysis.

Data collectionThe researcher employed a convenience sampling method with self-administered questionnaire surveys to collect the data. The researcher manually filtered 3,000 SMEs that met the requirement from DBD DataWarehouse+ and employed the random function in Excel to select 1,000 samples randomly. Although the figure of 1,000 firms was chosen based on the researcher’s capacity to manage the data, it aligns with sample selection commonly used in previous studies (Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, 2020; Purkayastha et al., 2022). The selected companies received the questionnaire surveys and cover letters via email. The researcher also distributed the paper-based surveys to companies in the Bangkok area. All distributed surveys were followed up through phone calls after a week.

To ensure the appropriateness and quality of the participants, the researcher included screening questions to confirm whether respondents held management positions and had been working since 2020 or earlier. A total of 1,000 web-based and paper-based survey questionnaires were distributed, and 224 responses were gathered. Out of 224 responses, 11 were removed due to missing components and poor quality. Thus, 213 valid responses remained; the response rate was approximately 21.3%. Nevertheless, the researcher was able to collect more than the minimum required sample size of 156.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the 213 sampled firms. The majority of respondents were SME owners, accounting for 39% (83 respondents), followed by general managers at 36.2% (77 respondents). The remaining included sales managers (9.9%, 21 respondents), finance or accounting managers (7.5%, 16 respondents), marketing managers (3.8%, 8 respondents), and other management roles (3.8%, 8 respondents). This distribution indicates a well-balanced representation of key decision-makers across different functional areas within SMEs. In terms of business structure, 47.9% (102 firms) operated as sole proprietorships or enterprises, 38.0% (81 firms) were private limited companies, and 14.1% (30 firms) were partnerships or joint ventures. The inclusion of various legal forms reflects the diversity of SME ownership and operational models. Firm age was also well-distributed: 28.6% (61 firms) had been in operation for over 20 years, 25.8% (55 firms) for 6–10 years, 17.8% (38 firms) for 11–15 years, 15.5% (33 firms) for 4–5 years, and 12.2% (26 firms) for 16–20 years. This spread across different age groups enhances the representativeness of the sample, allowing insights into both established and newer SMEs. Overall, the diverse composition of roles, business structures, and firm ages suggests that the sample provides a robust and representative overview of the Thai SME sector.

Respondent characteristics (n=213).

Note: The currency is converted to USD using an exchange rate of 1 USD = 32 Thai Baht for the annual revenue.

To assess the research model, the researcher used SEM, which is one of the most advanced practical statistical analysis techniques recently used in the social sciences. SEM is a second-generation technique that overcomes the weaknesses of first-generation methods, such as regression analysis (Hair et al., 2016). It is a class of multivariate techniques that combines factor analysis and regression (Hair et al., 2016). With SEM, the researcher can simultaneously perform confirmatory factor analysis and multiple regression analysis. In other words, it enabled the researcher to simultaneously test the relationships among measured and latent variables, as well as among latent variables.

Although the most widely used method is covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM), variance-based PLS-SEM or PLS path modelling has become a vital research method today. PLS was used as the study’s primary goal was theory development rather than theory testing. PLS is recommended for this kind of research (Hair et al., 2022). PLS-SEM has many advantages over CB-SEM, especially in social science research. According to Reinartz et al. (2009), ‘PLS requires only half of the observations to achieve a given level of statistical power compared to methods based on covariance with maximum likelihood’ (p. 334). Additionally, the method is suitable when many latent variables are studied but the sample size is not large (Chin, 2010).

SmartPLS software package, version 4.1.0.9, was used for data analysis. The researcher analysed the PLS model using the two-step approach of Chin (2010). First, the reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed to ensure the measurement model’s quality, focusing on the constructs’ reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Second, the structural model was assessed to investigate the causal relationships identified in the proposed model.

ResultsAnalysis of measurement modelAll the outer loading values are statistically significant and greater than 0.7 (see Table 3). Thus, the items used to measure the latent variables in this research model have indicator reliability (Hair et al., 2022). For assessing internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s alpha (α) values, composite reliability (ρC), and the reliability coefficient (ρA) were measured for each construct. The α value of each construct ranged from 0.869 to 0.949, meaning all constructs were acceptable based on the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Additionally, ρC and ρA values of all constructs were greater than 0.70; therefore, they are acceptable.

Measurement model.

To assess convergent validity, the researcher evaluated the average variance extracted (AVE) values based on the minimum threshold of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2022). The size of AVE was in the range of 0.675 to 0.740, which exceeded the minimum threshold, indicating that the measurement items for each construct consistently capture the same underlying concept (Hair et al., 2022).

Furthermore, the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) was employed to assess the discriminant validity of the constructs. The threshold of the HTMT criterion is 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), and the measurement model results in Table 4 are below the threshold.

Moreover, all variance inflation factor (VIF) values for both inner and outer models are less than five. Thus, common method bias is not an issue for this study (Kock, 2015).

Analysis of structural modelThe bootstrapping method with 5000 randomly generated sub-samples was used in this study to determine the measurement and structural level of coefficients’ statistical significance for the structural model. To assess nomological validity, structural evaluation was conducted to evaluate the size and significance of path coefficients, the coefficient of determination (R2), the effect size (f2), and the predictive relevance (Q2predictive), along with the comparison of root mean squared errors (RMSE) and mean absolute errors (MAE) between PLS and linear models (Hair et al., 2022).

R2 values represent a measure of the model’s in-sample predictive power (Chin, 2010; Rigdon, 2012; Sarstedt et al., 2014). The R2 of 0.452 in INQ indicates that 45.2% of the variance in INQ was explained by the independent variables, ACAP and KOL. Organisational resilience capabilities were explained by the latent variables: R2 for AC = 0.305, R2 for CC = 0.283, and R2 for ADC = 0.550 (see Fig. 3). In other words, the exogenous variables explain 30.5% of the variance in AC, 28.3% of the variance in CC, and 55.0% of the variance in ADC. Although an R2 value of 0.283 for a construct is small, several scholars have claimed that R2 is context-dependent, and a value above 0.26 indicates that the model has substantial explanatory power (Cohen, 1988; Hair et al., 2019).

Cohen (1988) suggests f2 values of 0.02 as small, 0.15 as medium, and 0.35 as large effect sizes. According to the model results, ACAP does not show a direct effect on AC (f2 = 0.010), CC (f2 = 0.003), and ADC (f2 = 0.002), but it has a medium effect size on INQ (f2 = 0.200). Conversely, KOL shows small effect sizes on CC (f2 = 0.027), ADC (f2 = 0.049), and INQ (f2 = 0.133). However, no direct effect from KOL on AC (f2 = 0.010) is detected. Furthermore, INQ possesses small effect sizes on all organisational resilience capabilities: AC (f2 = 0.062), CC (f2 = 0.110), and ADC (f2 = 0.051).

Finally, Q2predict values of all manifesting and latent variables are higher than zero, predicting that the model has predictive relevance. RMSE and MAE are checked for each indicator on the PLS and linear models. The RMSE and MAE values of all indicators on the PLS model are less than those of the linear model, confirming the high predictive power of the structural model (Hair et al., 2022).

Hypothesis testingThe positive influences of INQ on all three organisational resilience capabilities, AC (β = 0.292, p < 0.01), CC (β = 0.268, p < 0.05), and ADC (β = 0.312, p < 0.01), are significant. Thereby, H1a, H1b, and H1c are supported. However, the results indicate that H2a (β = 0.114, p > 0.05), H2b (β = 0.069, p > 0.05), and H2c (β = 0.039, p > 0.05) are not supported. Moreover, the positive significant effect of ACAP on INQ is supported by the result of β = 0.413 and p < 0.01. Thus, H3 is supported. In terms of KOL, the positive effect of the construct is significant on CC (β = 0.235, p < 0.05) and ADC (β = 0.249, p < 0.05), but not significant on AC (β = 0.141, p > 0.05). Therefore, only H5b and H5c are supported. H6, KOL positively affects the organisation’s INQ, which is also supported by β = 0.337 and p < 0.05. In terms of control variables, none of the variables significantly influences the three resilience capabilities (See Table 5).

Structural model: direct effect.

| Hypotheses | Path | Coefficients | T-statistics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | IQN → AC | 0.292⁎⁎⁎ | 3.651 | Supported |

| H1b | IQN → CC | 0.268⁎⁎ | 2.412 | Supported |

| H1c | IQN → ADC | 0.312⁎⁎⁎ | 4.189 | Supported |

| H2a | ACAP → AC | 0.114 | 1.098 | |

| H2b | ACAP → CC | 0.069 | 0.643 | |

| H2c | ACAP → ADC | 0.039 | 0.42 | |

| H3 | ACAP → INQ | 0.413⁎⁎⁎ | 4.405 | Supported |

| H5a | KOL → AC | 0.141 | 1.085 | |

| H5b | KOL → CC | 0.235⁎⁎ | 1.846 | Supported |

| H5c | KOL → ADC | 0.249⁎⁎ | 2.262 | Supported |

| H6 | KOL → INQ | 0.337⁎⁎ | 3.205 | Supported |

| Control Variables | Firm Age → AC | -0.106 | 1.787 | |

| Firm Age → CC | -0.069 | 1.029 | ||

| Firm Age → ADC | -0.026 | 0.53 | ||

| Firm Size → AC | 0.027 | 0.337 | ||

| Firm Size → CC | -0.101 | 1.289 | ||

| Firm Size → ADC | 0.021 | 0.305 | ||

| Revenue → AC | 0.117 | 1.54 | ||

| Revenue → CC | 0.098 | 1.185 | ||

| Revenue → ADC | 0.006 | 0.09 |

Notes:

*p < 0.05

The researcher followed Zhao et al. (2010) to determine (1) the presence of indirect effect and (2) the type of mediation, if one exists. The scholars explained that no indirect effect indicates no mediation in the relationship. However, significant indirect effects need further assessment to determine the significance of the direct effect and identify the type of mediation, that is, full mediation or partial mediation (Hair et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2010).

According to the structural model results, the direct effects of ACAP on organisational resilience capabilities, AC, CC, and ADC, are insignificant. However, the indirect effects between ACAP and two capabilities, AC (β = 0.121, p < 0.05) and ADC (β = 0.129, p < 0.05), through INQ are significant. Thus, INQ has full mediation effects in the relationships between ACAP and two organisational resilience capabilities, AC and ADC. Thereby, H4a and H4c are supported. Nevertheless, H4b, the mediation effect of INQ in the relationship between ACAP and CC, is rejected since no significant indirect effect (β = 0.111, p > 0.05) is detected in the analysis.

As mentioned in the previous section, although KOL showed significant direct effects on CC and ADC, no significant direct effect resulted on AC. The indirect effects between KOL and organisational resilience capabilities, AC (β = 0.098, p < 0.05), CC (β = 0.090, p < 0.05), and ADC (β = 0.105, p < 0.05), through INQ are significant, pointing in the same positive direction as the direct effect. Therefore, INQ has a full mediation effect in the relationship between KOL and AC, but shows complementary or partial mediation effects in the relationships between KOL and the other two organisational resilience capabilities, CC and ADC. Thereby, H7a, H7b, and H7c are supported (See Table 6).

Structural model: mediation.

| Hypo: | Path | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | T-statistics | Results | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | INQ → AC | 0.292⁎⁎⁎ | 3.651 | |||

| H1b | INQ → CC | 0.268⁎⁎ | 2.412 | |||

| H1c | INQ → ADC | 0.312⁎⁎⁎ | 4.189 | |||

| H2a | ACAP → AC | 0.114 | 1.098 | |||

| H2b | ACAP → CC | 0.069 | 0.643 | |||

| H2c | ACAP → ADC | 0.039 | 0.42 | |||

| H3 | ACAP → INQ | 0.413⁎⁎⁎ | 4.405 | |||

| H4a | ACAP → INQ → AC | 0.121⁎⁎ | 2.969 | Supported | Full | |

| H4b | ACAP → INQ → CC | 0.111 | 1.865 | |||

| H4c | ACAP → INQ → ADC | 0.129⁎⁎ | 3.085 | Supported | Full | |

| H5a | KOL → AC | 0.141 | 1.085 | |||

| H5b | KOL → CC | 0.235⁎⁎ | 1.846 | |||

| H5c | KOL → ADC | 0.249⁎⁎ | 2.262 | |||

| H6 | KOL → INQ | 0.337⁎⁎ | 3.205 | |||

| H7a | KOL → INQ → AC | 0.098⁎⁎ | 2.168 | Supported | Full | |

| H7b | KOL → INQ → CC | 0.090⁎⁎ | 2.268 | Supported | Partial | |

| H7c | KOL → INQ → ADC | 0.105⁎⁎ | 2.575 | Supported | Partial |

Notes:

*p < 0.05

Although the results demonstrate the significant moderating effect of OU on the relationship between KOL and ADC (β = 0.109, p < 0.05), no significant moderating effect is found on the relationship between KOL and the other two organisational resilience capabilities, AC (β = -0.046, p > 0.05) and CC (β = 0.075, p > 0.05). Thus, only H8c is supported, while the other two are rejected. For hypothesis 9, only the moderating effect of CI on the relationship between ACAP and AC (β = 0.128, p < 0.05) is significant. Thus, it is concluded that there is no significant moderating effect of CI on the relationships between ACAP and the other two resilience capabilities, CC (β = 0.000, p > 0.05) and ADC (β = -0.028, p > 0.05). Thereby, only H9a is supported while the other two are rejected (See Table 7).

Structural model: moderation.

| Hypotheses | Relationship between Constructs | Coefficients | T-statistics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8a | KOL x OU → AC | -0.046 | 0.927 | |

| H8b | KOL x OU → CC | 0.075 | 1.154 | |

| H8c | KOL x OU → ADC | 0.109⁎⁎ | 2.039 | Supported |

| H9a | ACAP x CI → AC | 0.128⁎⁎ | 1.975 | Supported |

| H9b | ACAP x CI → CC | 0.000 | 0.007 | |

| H9c | ACAP x CI → ADC | -0.028 | 0.52 |

Notes:

*p < 0.05

Additionally, Hair et al. (2022) suggested assessing the moderation effect’s strength, the effect size (f2), when interpreting the results. Thus, the researcher evaluated the f2 values of the significant moderation effects. According to Kenny (2018), the interaction term effect sizes of 0.0005, 0.01, and 0.025 indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The f2 value of OU’s significant moderation effect on the relationship between KOL and ADC is 0.044, indicating a large effect size. Similarly, the moderation effect of CI on the relationship between ACAP and AC demonstrates the large effect size of the f2 value of 0.025.

DiscussionThe study’s results indicate that INQ positively influences the development of all three organisational resilience capabilities, highlighting that robust innovation performance contributes to resilience when facing disruptions. In other words, effective organisational resilience is best predicted by high INQ, characterised by standardisation, low error tolerance, and systematic procedures. While the current study emphasises INQ, this finding aligns with various past studies indicating that different types of innovations positively contribute to fostering organisational resilience to a certain extent (Ahn et al., 2018; Senbeto & Hon, 2020).

In contrast, ACAP does not have a significant direct impact on fostering any organisational resilience capabilities. A possible explanation is that while ACAP enables firms to acquire and assimilate external knowledge, this knowledge alone does not automatically translate into proactive risk assessment, immediate crisis response, or adaptive transformation. Resilience requires more than possessing knowledge, as it depends on how effectively firms apply, integrate, and act upon that knowledge in dynamic environments. Although SMEs are typically characterised by flexibility and flatter organisational structures that allow agile responses to change, their ability to translate absorbed knowledge into organisational resilience may still be constrained by underdeveloped knowledge management systems or the absence of formalised absorptive mechanisms.

However, ACAP’s indirect effect through INQ is significant for AC and ADC, implying that INQ fully mediates these relationships. This suggests that while ACAP facilitates knowledge absorption and transformation for commercial usage in SMEs during disruptions, it does not directly enhance organisational resilience capabilities. Instead, SMEs must ensure that innovations and changes derived from ACAP are of sufficient quality to respond effectively to disruptions, particularly in the anticipation and adaptation stages. Although no significant direct effect of ACAP on resilience capabilities was found in this study, the importance of knowledge-based resources and capabilities to survive in a dynamic business environment remains prominent (Mafabi et al., 2012; Orth & Schuldis, 2020; Yu et al., 2021).

Additionally, the study examines the antecedent role of KOL in enhancing organisational resilience capabilities. The findings show that KOL significantly influences CC and ADC, indicating that knowledge-oriented leaders are vital for SMEs in managing different crisis stages. KOL promotes organisational learning and equips SMEs with better coping and adaptation capabilities during and after disruptions. Organisational resilience capabilities require extensive learning processes for different resilience stages (Evenseth et al., 2022). Knowledge-oriented leaders facilitate those learning processes by inspiring, rewarding, motivating, and communicating with the members of organisations.

However, no significant effect of KOL is found on AC. This finding may be due to the nature of Thai SMEs. KOL in SMEs may primarily emphasise day-to-day knowledge management activities rather than strategic scanning or proactive foresight, which are more commonly observed in larger corporations. This operational focus may explain the absence of a direct effect on AC. Furthermore, the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic could have influenced this result, as almost no businesses were able to foresee such a global crisis. The novelty and unpredictability of the event likely limited the effectiveness of anticipatory efforts, regardless of leadership orientation.

Although KOL directly affects only two capabilities, its indirect effect through INQ impacts all three: AC, CC, and ADC. A full mediation effect of INQ exists in the relationship between KOL and AC, while INQ imposes partial mediation on the relationships between KOL and the other two capabilities. This underscores that while knowledge-oriented leaders play an important role in making SMEs resilient, the effectiveness of the innovation created by those leaders also determines the extent to which SMEs can anticipate, cope, and adapt to disruptive situations.

Moreover, the positive significant impact of ACAP on INQ is congruent with the past study of Grimpe and Sofka (2009), who claimed that firms with high ACAP are better positioned to achieve high INQ. These firms are more proficient in managing their R&D processes, resulting in efficient and higher-quality innovation outcomes. Similarly, the finding of KOL’s significant positive influence on INQ aligns with several past studies (Chaithanapat et al., 2022; Zia, 2020). This finding suggests that SMEs with leaders who motivate learning and tolerate mistakes create an environment that nurtures better INQ. Such an environment allows firms to adapt effectively to disruptions and enhances their resilience capabilities.

The study also explored OU as a moderator between KOL and organisational resilience capabilities. OU does not significantly moderate the relationship between KOL and AC or CC, only moderating the relationship between KOL and ADC. This means that the impact of KOL on fostering ADC is evident in SMEs that are willing to discard obsolete knowledge. The finding partially supports Morais-Storz and Nguyen’s (2017) explanation of unlearning as an important component for building organisational resilience and effective learning. According to this study’s findings, OU enhances the effectiveness of KOL in creating ADC.

Finally, CI was also proposed as a moderator in the relationship between ACAP and organisational resilience capabilities. However, only one significant moderation effect of CI on the relationship between ACAP and AC was evident. This indicates that SMEs operating in highly competitive industries tend to have a higher ability to absorb knowledge and transform it for superior performance. The finding is congruent with Jones and Linderman’s (2014) claim that as competition intensifies, organisations must innovate their products and processes to remain competitive.

ConclusionThis study highlights the pivotal role of INQ, KOL, and ACAP in enhancing organisational resilience capabilities among SMEs, based on the findings of 213 Thai SMEs. The findings reveal that high-quality innovation, characterised by standardisation, low error tolerance, and systematic procedures, directly strengthens anticipation, coping, and adaptation capacities in times of disruption. While ACAP does not show a direct effect on resilience capabilities, its influence is fully mediated through INQ for anticipation and adaptation. This underscores that simply acquiring and assimilating external knowledge is insufficient; SMEs must also transform that knowledge into high-quality innovations to respond effectively to crises. Similarly, KOL significantly contributes to coping and adaptation capabilities, both directly and indirectly through INQ, reinforcing the importance of leaders fostering learning and innovation within the organisation.

Additionally, the study underscores the importance of OU and CI in shaping resilience outcomes. OU is found to moderate the relationship between KOL and ADC, suggesting that the ability to discard obsolete knowledge enhances leaders’ effectiveness in building adaptive capacity. CI moderates the relationship between ACAP and AC, indicating that firms in highly competitive environments are better positioned to leverage absorbed knowledge for proactive resilience. Overall, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on SME resilience by identifying how knowledge-based factors and INQ interact to support firms in dynamic and uncertain conditions. The findings offer valuable implications for SMEs seeking to build long-term resilience through strategic innovation and leadership practices.

Theoretical implicationsSince this study assesses effects rarely studied in the literature, (1) the mediating effect of INQ in the relationship between ACAP and three organisational resilience capabilities; (2) the mediating effect of INQ in the relationship between KOL and three organisational resilience capabilities; (3) the moderating effect of CI on the relationship between ACAP and three organisational resilience capabilities; and (4) the moderating effect of OU on the relationship between KOL and three organisational resilience capabilities in SMEs, this study and its findings are considered new empirical research that contribute to the literature on KOL, CKM, innovation, and firm performance variables.

Additionally, this study fills the knowledge gap identified in previous research claiming that different leadership styles and behaviours influence organisational resilience (de Oliveira Teixeira & Werther Jr, 2013; Teo et al., 2017). The findings also support Ayoko's (2021) editorial suggestion to explore the relationship between leadership and resiliency, since different leadership styles affect resilience at various levels during crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The knowledge gap noted by Orth and Schuldis (2020) and Evenseth et al. (2022), which stated that the field of unlearning research is not well established and could benefit from more empirical studies, has also been addressed. The current research’s finding of OU as a moderator of the relationship between KOL and ADC in SMEs contributes to these research gaps in the context of organisational resilience.

Managerial implicationsThis study highlights the important role of ACAP in building SMEs’ organisational resilience by leveraging knowledge resources. Managers and practitioners can gain valuable insights into managing knowledge-based resources and capabilities to enhance resilience in their organisations. The study also underscores the significance of KOL, a novel leadership style that fosters resilience capabilities. Given the typically limited resources of SMEs, managers must strategically invest in processes that improve their firms’ ability to identify and utilise relevant external knowledge.

While SMEs may have the ability to exploit valuable knowledge resources for anticipating, coping, and adapting, ineffective innovations or changes can hinder organisational resilience. Thus, improving INQ can facilitate the effective utilisation of knowledge and nurture organisational resilience for SMEs. The study also emphasises that recognising the potential of unlearning in fostering resilience is vital for dynamic environments. For many SMEs, holding on to outdated routines, practices, or mental models can be detrimental, particularly in fast-changing environments. Therefore, organisations should not hesitate to remove obsolete beliefs, norms, and understandings to allow new and appropriate knowledge.

In contrast, the role of CI was also highlighted in this study. Managers and owners of SMEs need to understand the competitiveness of their industry. Those operating in highly competitive industries should focus more on promoting ACAP and KOL. This ensures they are well-equipped with resilience capabilities to overcome crises and remain competitive in their industry.

Limitations and future research directionsWhile this study offers valuable contributions, it is not without limitations. The first limitation is that it was conducted in the post-pandemic period. Consequently, participants’ responses regarding their experiences before and during the pandemic are retrospective, which might affect the accuracy of their accounts. Although the samples were carefully collected from SMEs operating in various industries in Bangkok, the sample size is relatively small due to several difficulties, limiting the generalisability of the results. For future studies, collaborating with industry associations or government organisations supporting SMEs can help increase the sample size. Moreover, the study does not explicitly incorporate COVID-19-specific variables in the conceptual model. Therefore, future studies could extend this work by integrating firm-level data on specific aspects of the crisis under investigation.

Additionally, conducting similar studies in specific industries, such as restaurants and tourism, could provide industry-specific insights. Researchers might also consider applying this research model to larger corporations. Moreover, this study analysed three different organisational resilience capabilities related to different stages of a crisis. Future studies should consider these three capabilities as first-order constructs and measure organisational resilience as a second-order formative construct to create a parsimonious conceptual model. Moreover, this study primarily focused on the moderating effects of OU and CI, overlooking other potential moderating variables. Factors such as social capital, trust, networks, and relationships between firms could play a critical role in how SMEs respond to crises. Future studies should consider these variables to better understand the relationships among the studied variables.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNay Chi Khin Khin Oo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sirisuhk Rakthin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Constructs Measurement and Items

| Construct | Items/ Indicators | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Absorptive Capacity | Our firm… | Adapted from Pavlou and El Sawy (2006) |

| (1) is successful in learning new things. | ||

| (2) is effective in developing new knowledge or insights that have the potential to influence product development. | ||

| (3) is able to identify and acquire internal (e.g. within the group) and external (e.g. market) knowledge. | ||

| (4) has effective routines to identify, value, and import new information and knowledge. | ||

| (5) has adequate routines to analyse the information and knowledge obtained. | ||

| (6) has adequate routines to assimilate new information and knowledge. | ||

| (7) can successfully integrate the existing knowledge with the new information and knowledge acquired. | ||

| (8) is effective in transforming existing information into new knowledge. | ||

| (9) can successfully exploit internal and external information and knowledge into concrete applications. | ||

| (10) is effective in utilising knowledge into new products. | ||

| Knowledge-oriented Leadership | Over the last three years, | Adapted and developed from Donate and de Pablo (2015); Chaithanapat et al. (2022) |

| (1) Our management leadership has been creating an environment for responsible employee behaviour and teamwork. | ||

| (2) Our management is used to assuming the role of knowledge leaders, which is mainly characterised by openness, tolerance of mistakes, and mediation for the achievement of the firm’s objectives. | ||

| (3) Our management promotes learning from experience, tolerating mistakes up to a certain point. | ||

| (4) Our management behaves as advisers, and controls are just an assessment of the accomplishment of objectives. | ||

| (5) Our management promotes the acquisition of external knowledge. | ||

| (6) Our management rewards employees who share and apply their knowledge. | ||

| (7) Our management promotes the acquisition of external knowledge about the firm’s image. | ||

| (8) Our management rewards employees who share and apply their firm’s image-related knowledge. | ||

| Innovation Quality | Our firm has good performance in… | Adapted from Taherparvar et al. (2014); Wang and Wang (2012) |

| (1) generating new ideas. | ||

| (2) launching a new product or service. | ||

| (3) using new technology and equipment. | ||

| (4) solving customers’ problems. | ||

| Anticipation Capability | Before facing business difficulties caused by disruptions (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) , our firm… | Adapted from Rai et al. (2021); Duchek (2020) |

| (1) is able to forecast the regular disruption to operations. | ||

| (2) collects the data of even small disruptions. | ||

| (3) shares the disruption data with other organisations. | ||

| (4) invests in an information system that can predict the upcoming turbulence. | ||

| (5) was able to predict the crisis before it hit our operations. | ||

| (6) was able to anticipate the upcoming challenges when the pandemic was at a very early stage. | ||

| Coping Capability | When facing the business difficulties caused by disruptions (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) , our firm… | Adapted and developed from Duchek (2020); Shaya et al. (2022) |

| (1) easily accepts the plausibility of crisis situations and failures. | ||

| (2) possesses resources to mitigate the effects of disruptions. | ||

| (3) has the ability to effectively handle the disrupted situation. | ||

| (4) handles the problems effectively and maintains the business continuity under the impact of disruptions. | ||

| Adaptation Capability | After facing the business difficulties caused by disruptions (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) , our firm… | Adapted and developed from Ma and Zhang (2022); Duchek (2020); Shaya et al. (2022) |

| (1) quickly understands changes in market demand. | ||

| (2) has ability to learn from the experiences, reflect on them, and adjust correctly for the business continuity. | ||

| (3) is very cautious about changes in the industry. | ||

| (4) has ability to adjust internal operation process according to changing environment. | ||

| Competitive Intensity | In our industry, | Adapted from Grewal and Tansuhaj (2001); Jaworski and Kohli (1993) |

| (1) competition is cutthroat. | ||

| (2) there are many ‘promotion wars’. | ||

| (3) strong price competition is well known. | ||

| (4) we hear of a new competitive move almost every day. | ||

| Organisational Unlearning | Our firm… | Adapted from Casillas et al. (2010); Lyu et al. (2022) |

| (1) permits new knowledge, even when it conflicts with well-accepted experience and knowledge. | ||

| (2) provides favourable context for changing obsolete beliefs. | ||

| (3) is ready to change the way it operates. | ||

| (4) can establish new product processes based on real needs. | ||

| (5) is ready to abandon outdated beliefs and routines. |