In the digital economy, corporate digital technology innovation is considered pivotal for reshaping industrial competitiveness and establishing national strategic advantages. Using data from China's A-share listed companies from 2007 to 2023, this study examines the influence of government digital subsidies on corporate digital technology innovation and its underlying mechanisms. Government digital subsidies are identified using the BERT language model. Meanwhile, International Patent Classification information is employed to discern digital patents, as a measure of corporate digital technology innovation. The findings reveal that government digital subsidies significantly stimulate corporate digital technology innovation, with this result remaining robust across multiple robustness checks and endogeneity controls. Mechanism analysis reveals three mechanisms: alleviating financing constraints, enhancing R&D willingness, and strengthening digital strategic deployment. Furthermore, government digital subsidies have significantly stronger effects on digital strategic deployment in firms with a CEO who has an IT background and firms with a high level of artificial intelligence application. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the incentive effects are more pronounced in non-state-owned, growth stage, small firms, and firms located in regions with higher marketization levels or digital economic policy intensity. Further analysis shows that digital subsidies effectively promote both digital technology integration and pure digital technology innovations. However, digital innovation quality is negatively affected. This stems from the perverse “quantity-oriented” incentives of subsidies, which drives firms to prioritize application volume over technical depth. These findings contribute to government digital subsidy and digital innovation research while providing important implications for managers to achieve sustainability in the digital transformation context.

The digital economy has emerged as a pivotal driver of high-quality development. In particular, corporate digital technology innovation capabilities are a critical force for enhancing competitive advantages, accelerating industrial restructuring, and shaping future growth trajectories (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Porter & Heppelmann, 2014; Koch & Windsperger, 2017), fundamentally reshaping countries’ competitive landscapes (Teece, 2012). While distinct from conventional technological innovation, digital innovation also extends beyond the development of cutting-edge technologies like AI, big data, and blockchain. Crucially, it necessitates comprehensive organizational transformation across production processes, management systems, and business models, characterized by high integration, rapid diffusion, and iterative evolution (Barrett et al., 2015; Nambisan et al., 2017). However, digital innovation faces inherent challenges including substantial capital requirements, extended development cycles, and heightened uncertainty (Johansson et al., 2021). The innovation gap theory posits fundamental disparities between invention and commercialization (Branscomb & Auerswald, 2002). This is particularly pronounced in digital technology domains where conventional financing mechanisms prove inadequate. This context elevates government digital subsidies as crucial fiscal instruments for bridging innovation gaps and facilitating corporate digital transitions. Digital subsidies exhibit dynamic adaptability, distinguishing them from traditional static subsidy mechanisms. State policy on this is also increasingly shifting to the digital realm. For example, China's 12th Five-Year Plan emphasized the construction of a new generation of information infrastructure, while the 13th Five-Year Plan highlighted the acceleration of the development of 4G networks. In the 14th Five-Year Plan, the focus of government subsidies gradually shifted from the construction of 5G infrastructure to the research, development, and application of artificial intelligence (AI) models. This reflects the dynamic evolution of policy objectives in response to technological developments and changes in market demand. China's strategic prioritization of digital economy development has intensified since the 2024 Government Work Report emphasized advancing digital-technological integration with real economy sectors. This policy orientation underscores the urgency to investigate how government subsidy mechanisms stimulate corporate digital innovation, particularly through targeted fiscal interventions.

Extant scholarship predominantly examines generic innovation subsidies, yielding two contrasting perspectives. Some studies show subsidies' positive impacts on innovation enhancing innovation output or R&D investment (Zúñiga-Vicente et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2023; Han et al., 2024). Meanwhile, others identify potential distortions from information asymmetry and rent-seeking behaviors, which may crowd out long-term innovation resources (Zhang et al., 2015). Recent evidence suggests that compared with general fiscal support, digitally-targeted subsidies demonstrate superior efficacy in driving corporate digital transformation (Li et al., 2024). However, systematic analyses of their specific mechanisms remain underdeveloped. Other studies on digital innovation determinants identify multiple drivers including digital mergers (Hanelt et al., 2021), capability accumulation (Shakina et al., 2021), and infrastructure development (Wang et al., 2025). Despite these insights, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding the precise role of government digital subsidies in catalyzing enterprise-level digital technology innovation.

Moreover, few studies systematically examine the mechanisms through which government digital subsidies foster digital technology convergence. Digital convergence emphasizes the dynamic integration process across technological and industrial boundaries, and is a core innovation paradigm in the digital economy (Hund et al., 2021). However, the question of whether digital subsidies effectively promote such complex collaborative innovation remains underexplore. Additionally, while digital technologies exhibit strong positive externalities (Henfridsson & Bygstad, 2013), government subsidies may induce corporate rent-seeking innovation or path dependence, thereby distorting genuine innovation incentives. Frequent subsidies and low transparency may enable firms to treat subsidies as short-term profit tools, weakening long-term innovation capacity building. Hence, this study aims to deconstruct the intrinsic logic in driving technology convergence and further identify its impact on innovation quality.

Internationally, government-led corporate digital transformation has emerged as a critical context for research on strategic change. Through a case study of Ireland’s recently launched “Digital Start” program, Shirish (2025) found that government-initiated digital transformation projects not only generate considerable social value but also effectively stimulate microbusinesses to engage in innovation and adopt digital technologies. Thus, government support policies can play a significant enabling role in facilitating corporate digital transformation. Globally, fiscal interventions for promoting digital transformation exhibit marked institutional heterogeneity. In countries with robust institutional environments and sound property rights protection, government subsidies are typically targeted at correcting market failures, with a particular focus on supporting high-risk and high-uncertainty activities such as foundational technology research and algorithmic innovation. These areas often neglected by private capital. For instance, the German Federal Government has launched programs such as the “Industrial Cooperative Research Programme for SMEs (IGF)” project and “KMU-innovativ” program to fund cutting-edge joint research projects between small firms and research institutions. This demonstrates a gap-filling subsidy logic under conditions of high institutional quality. In European countries, subsidy policies emphasize a combination of government support and market-based mechanisms. Similarly, the Chinese government has played an active role in supporting the digital transformation of firms. However, compared to other countries, China exhibits significant differences in policy implementation mechanisms, market conditions, and institutional foundations. Given these contextual distinctions, understanding whether government-led digital subsidies in China can serve a similar catalytic role and assessing their effectiveness in comparison with the market-oriented models adopted in Europe is essential. This study is grounded in the institutional realities of China’s digital economy and draws on international experience to propose representative and generalizable recommendations for improving subsidy policies, aiming to enhance the external validity and global relevance of our findings.

Our contributions are threefold:

First, this study significantly advances research on government digital subsidies. The literature predominantly examines the economic impacts of innovation subsidies and green subsidies (Zuniga-Vicente et al., 2014), with limited attention to digitally-targeted instruments. Unlike traditional subsidies, digital subsidies explicitly pursue technology convergence and intelligent transformation with stronger policy orientation and integration imperatives. The key distinctions include the following: On the one hand, digital subsidies target digital infrastructure development and integrated technology applications, emphasizing system interoperability and data element synergy. On the other hand, digital subsidies create policy-aligned digital coordination effects, serving as incentives for small and medium enterprises’ (SME) digital innovation diffusion. Corporate digital technology innovation is a key concern for the development of the digital economy. Departing from conventional innovation subsidy studies, this study pioneers the micro-level analysis of government digital subsidies' impact mechanisms on corporate digital innovation, enriching institutional perspectives on technology convergence-driven innovation.

Second, methodologically, we employ the cutting-edge bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) language model to semantically identify digital subsidy projects aimed at digital transformation. This approach establishes direct measurement metrics for government digital subsidies, laying a microdata foundation for related theoretical and empirical research. Next, the Digital Economy and Core Industries Classification, and International Patent Classification (IPC) codes are adopted to delineate the technological domains for digital innovation. This approach is used to construct comprehensive and precise indicators of digital subsidy levels and digital technology innovation among Chinese listed companies. Furthermore, IPC codes are utilized to differentiate innovation types. Patents containing both digital and non-digital technology IPC codes are categorized as digital technology integration innovations. Those exclusively bearing digital technology IPC codes are classified as pure digital technology innovations. This classification refines the measurement of corporate digital innovation activities. This multidimensional indicator system provides robust tools for systematically evaluating the innovation effects of digital subsidies.

Third, in terms of the mechanisms, this study systematically examines the substantive impacts of government digital subsidies from multiple theoretical dimensions, including capital provision, behavioral motivation, and strategic cognition. It further constructs an analytical framework of “strategic deployment–organizational action–innovation output,” focusing on how firms translate strategic intent into concrete courses of action. By introducing key organizational mechanisms such as the formation of technological strategic alliances and optimization of high-skilled digital talent allocation, this study reveals the internal process through which subsidies facilitate the implementation of corporate digital strategies and realizing technological innovation. Thus, we help unravel the black box of subsidy effects from an integrated theoretical and practical perspective. Furthermore, we analyze the policy-induced innovation from a cross-domain digital innovation perspective. The findings reveal that under the incentives provided by the subsidies, firms prioritize responsive innovation over quality improvements. This critical observation deepens the understanding and evaluation framework for digital subsidy policy effectiveness.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: The second section outlines the theoretical background and research hypotheses. The third section presents the methods and data, while the fourth section discusses the empirical results. The fifth section focuses on mechanism and further analyses. Finally, the sixth section presents the conclusions and implications of this study.

Theoretical background and research hypothesisGovernment digital subsidies and corporate digital technology innovationYoo et al. (2010) first defined digital technology innovation as the process of combining digital and physical components to generate new products, services, and business models. Subsequent studies have further explored this concept (Ciriello et al., 2018). Broadly, digital technology innovation involves integrating information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies to drive technological advancements across product development, production process optimization, organizational transformation, and business model innovation (Liu et al., 2020; Hund et al., 2021). Its defining characteristics include the following: 1) Data Homogeneity, wherein innovation processes emphasize converting analog signals into digital formats through the combined use of information, computing, and communication technologies, enabling efficient digital device interoperability (Tilson et al., 2010). 2) Network Externality, wherein the homogeneous and reprogrammable nature of digital technologies fosters continuous iterative improvements, reducing entry barriers and learning costs while accelerating knowledge dissemination (Henfridsson & Bygstad, 2013; Henfridsson et al., 2018). 3) Technological Convergence, which blurs the boundaries between products, industries, organizations, and roles (Hund et al., 2021). These characteristics shape the operational logic and risk profile of digital innovation, posing distinct challenges: Substantial upfront infrastructure investments are required, while returns materialize only after prolonged periods and large-scale user adoption. This leads to extended payback cycles and heightened sunk costs.

Compared to traditional innovation, digital technology innovation exhibits fundamental differences in its mechanisms and policy requirements. On the one hand, traditional innovation typically follows a linear process from knowledge accumulation to commercialization. It emphasizes defined technical pathways, long-term knowledge accumulation, and stable intellectual property (IP) protection mechanisms. Conversely, digital technology innovation relies more on high-frequency data flows and rapid iterations (Nambisan et al., 2017). It prioritizes real-time feedback and multi-party collaboration, thus demonstrating high path dependency and outcome uncertainty. On the other hand, digital innovation features stronger network externalities and technology convergence characteristics. Its technological value is often co-created and dynamically evolved across multiple entities and platforms. While this model accelerates innovation diffusion, it significantly increases systemic risks of innovation failure.

Consequently, the key distinction of digital technology innovation lies in its emphasis on digital technology application throughout the innovation process. However, this also means that it faces greater uncertainties, higher R&D risks, and more severe resource constraints than conventional technological innovation. Moreover, traditional subsidy frameworks for innovation outcomes are often inadequate for digital technology innovation. Governments should implement continuous, phased, and platform-based subsidy mechanisms to guide firms in undertaking consistent investments and collaborative expectations regarding digital infrastructure, data openness, and cross-platform coordination. Therefore, the government digital subsidies examined in this study differ fundamentally from traditional innovation subsidies. Their purpose extends beyond reducing initial innovation costs to actively fostering digital ecosystem development, stimulating cross-boundary integration capabilities, and creating structural incentives for corporate digital innovation behaviors.

While firms possess endogenous motivations for technological innovation, inadequate resource allocation for innovation activities without government support poses significant challenges to digital technology innovation (Aghion & Howitt, 1992). By providing financial support, government subsidies not only offer essential resources for firms' innovation activities but also send positive signals that encourage firms to invest in digital technologies. Essentially, these subsidies correct market distortions caused by externalities, and thus, incentivize firms to engage in digital technology innovation. First, by providing upfront, non-repayable funds, government digital subsidies directly ease firms' financial constraints during the R&D process and lower the cost of digital innovation activities. In particular, the subsidies offer critical support for digital technology projects in the exploratory phase. Second, government digital subsidies orient firms towards digitization. These subsidies usually reflect government preferences for certain investment directions by issuing project application guidelines, key technology lists, or application scenarios. This guides firms to allocate resources toward strategic emerging fields such as AI, big data, industrial internet, and intelligent manufacturing. Moreover, collaborative innovation along the industrial chain can enhance regional digital ecosystems, further reinforcing the government's guiding role in digital technology innovation. Third, government digital subsidies serve a signaling function. When firms receive government digital subsidies, it signifies the official recognition of their technological potential and innovation capacity, sending positive signals to markets, financial institutions, and venture capital investors. This improves firms' financing abilities, playing a strategically important role in technology markets characterized by severe information asymmetry. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Government digital subsidies promote corporate digital technology innovation.

Financing constraints are a key barrier preventing firms from engaging in high-intensity, long-term innovation. This is especially in digital technology projects, which have high uncertainty, large upfront investments, and delayed returns. These capital bottlenecks often lead firms to abandon potential upgrades (Sprenger et al., 2017). Government digital subsidies help alleviate such constraints by removing resource barriers and supporting digital innovation through two main mechanisms. First, direct financial support reduces R&D costs. Unlike traditional innovation, digital innovation involves costly phases such as system development, data platform construction, talent acquisition, and integration of emerging technologies (Nambisan et al., 2017; Rippa & Secundo, 2019; Johansson et al., 2021). Firms often face funding shortages as internal resources fall short. Grants and upfront subsidies provide crucial capital, lowering cost burdens and enhancing firms’ risk tolerance (Shao & Chen, 2022). Second, subsidies create signaling effects that attract market resources. Government endorsement reduces information asymmetry, sending positive signals to banks and investors, thereby improving firms’ creditworthiness, bargaining power, and access to diverse financing channels (Chen et al., 2020).

Moreover, alleviating financing constraints provides essential capital safeguards, enhancing cross-technology integration and driving the initial momentum for convergent innovation. First, in the digital economy, firms often face high-convergence challenges involving multiple technologies and systems. Significant upfront investments in infrastructure, integration platforms, and cross-disciplinary talent are needed. Looser constraints offer the requisite seed funding to overcome the resource barriers to such integration. Second, digital innovation relies less on isolated R&D, and more on platform-based collaboration and cross-industry integration. With greater financial flexibility, firms are more capable and willing to participate as core nodes in collaborative networks, strengthening their position in digital ecosystems (Zhang et al., 2023). Finally, unlike traditional manufacturing, digital innovation depends on intangible assets such as data, algorithms, IP, and organizational coordination. Relaxed financing constraints promote investment in these areas, fostering soft-resource-driven innovation and building core competitiveness (Xu et al., 2020). Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 Government digital subsidies can promote corporate digital technology innovation by alleviating financing constraints.

According to expected utility theory, firms weigh the potential returns against the investment costs when making R&D decisions. Digital technology projects have high uncertainty, failure risks, unclear technical paths, ambiguous market acceptance, and long payback periods. Hence, firms tend to exhibit risk aversion, favoring conventional, path-dependent innovations with higher perceived success rates (Bohnsack et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2015). Government digital subsidies can mitigate this tendency by enhancing R&D willingness and stimulating endogenous innovation through two behavioral mechanisms. First, subsidies serve as risk-mitigation tools. By sharing innovation risks, they reduce the financial losses and opportunity costs of failure, raising expected returns and strengthening firms’ motivation for undertaking digital R&D (Zhao et al., 2024). Second, subsidies provide strategic guidance. Through funding criteria and policy priorities, governments influence firms’ technological choices, encouraging them to pursue digital innovation paths (Zhang et al., 2024; Lerner, 2000). Additionally, subsidy recipients must meet standardized requirements that embed digital innovation into long-term strategies, promoting more systematic and aligned innovation efforts (Yang et al., 2025).

Enhancing R&D willingness is not merely a shift in resource allocation but a fundamental prerequisite and internal driver for undertaking complex innovation. First, stronger R&D intentions stimulate cross-departmental coordination and resource integration, prompting firms to restructure innovation capital, and promote synergy between technology and business. To pursue convergent innovation, firms dissolve technological boundaries and deepen their embeddedness in digital ecosystems. Second, R&D willingness reflects not only resource commitment but also a shift in strategic logic (Zhu et al., 2024). When firms view digital innovation as the key to future growth, they adapt organizational structures, institutions, and incentives. This transformation fosters deep competitive shifts and systematically supports digital convergence. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 Government digital subsidies can promote corporate digital technology innovation by enhancing R&D willingness.

Digital technology innovation goes beyond technical upgrades, requiring organizational restructuring across business processes and governance systems. This increases the demands on firms’ strategic planning and coordination (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2014; Porter & Heppelmann, 2014; Yoo et al., 2010). Government subsidies enhance managerial preference for high-risk innovation (Bronzini & Piselli, 2016). Thus, it can reinforce executive commitment to digital technology innovation. This can motivate firms to pursue ambitious initiatives through two mechanisms. First, the subsidy application and implementation process compels firms to develop detailed digital transformation plans, funding schemes, R&D targets, and performance metrics. This institutional mechanism prompts executives to assess digital capabilities, identify bottlenecks, and drive top-down strategic restructuring (Lu et al., 2025). Meanwhile, to seize market opportunities and first-mover advantages (Wu & Gong, 2018), the management is incentivized to prioritize digital innovation. Second, policy-driven regulations and oversight standardize corporate behavior and elevate digital innovation within the internal firm’s governance (Lyu et al., 2024), triggering institutional adjustments in structure and decision-making. Together, these pressures reposition digital innovation as a core strategic priority, accelerating the shift toward data-driven organizational models (Xie et al., 2022).

Essentially, the impact of digital strategy deployment on corporate digital technology innovation is a complex, multi-layered process involving management decisions, resource allocation, organizational capability building, and external collaboration. Strengthening digital strategy deployment realigns a firm's resources, organizational mechanisms, and ecosystem positioning toward digital integration and innovation. First, elevating digital technologies from merely providing peripheral support to core strategic priority prompts the top management to define their value, development trajectory, and integration paths, offering institutional direction for cross-technology integration (Saha et al., 2018). This top-down emphasis clarifies digital transformation goals across departments, guiding R&D teams and enhancing innovation efficiency and success rates. Second, beyond internal alignment, digital strategy deployment is reflected in the firm’s proactive engagement in technological alliances. This indicates a shift from internal awareness to active collaboration with tech firms, thereby accelerating innovation and ensuring strategy execution. Through partnerships such as joint labs or co-invested R&D platforms, firms can rapidly integrate AI and other technologies into products and services, forming collaborative innovation ecosystems. These alliances lower barriers to large-scale digital innovation and enable breakthroughs that are difficult to achieve independently (Stuart, 2000).

Hypothesis 4 Government digital subsidies can promote corporate digital technology innovation by strengthening digital strategic deployment.

Our core variables include government digital subsidies and corporate digital technology innovation. Government digital subsidy data were sourced from the CSMAR database, while digital technology innovation indicators were obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS). For mechanism variables, the digital strategic deployment and CEO’s IT background data were derived from keyword extraction of listed companies' annual reports. Data on financing constraints, R&D intention, and degree of application of AI data were obtained from the CSMAR database.

The manual collection of government digital subsidies data begin in 2007. Hence, we selected A-share listed companies from the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2007 to 2023 as the research sample. From these, samples of ST, *ST, and PT companies, financial firms, and observations with missing values were excluded. The final sample comprised 4680 listed firms, yielding a total of 44502 initial observations. To mitigate the influence of outliers, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1 % level on both tails.

Explained variable: digital technology innovation (Digtech)First, we obtained Chinese invention patent data from the Innovation Patent Research module of the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS), and matched invention patents to listed companies based on patent applicant names. Second, using the IPC classification information for digital technology patents provided in the “Digital Economy Core Industry Classification and International Patent Classification Cross-Reference Table (2023)”, we identified and matched the IPC numbers of listed companies' invention patents. Patents whose IPC classification codes fell within the digital technology IPC pool were designated as digital patents. Finally, we applied logarithmic transformation to the filtered digital patent data.

Core explaining variable: government digital subsidy (Subsidy)Studies generally adopt the innovation subsidy division method proposed by Guo (2018), which screens and retrieves government subsidies through keyword matching. However, this approach is susceptible to subjective factors during data processing, including keyword selection criteria, matching rules, and contextual ambiguities. This can inevitably lead to information omission and measurement bias that can compromise the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the subsidy variables (Hong et al., 2023). Conversely, deep learning models like BERT can effectively overcome these limitations (Miric et al., 2023). With robust semantic understanding and contextual reasoning capabilities, BERT captures diverse linguistic variations and expressions. Through unsupervised pre-training on large-scale corpora, BERT acquires generalized language comprehension that significantly outperforms shallow representations of traditional machine learning models (e.g., support vector machine, random forest, and XGBoost) (Huang et al., 2023). Therefore, when measuring government digital subsidies, the BERT approach substantially enhances accuracy and intelligence compared to traditional keyword methods and other ML models, representing an ideal upgraded alternative.

The standard procedure for classifying government subsidies using BERT comprises three steps, as shown in Fig. 1.

First, we performed pre-training using Google's Chinese pre-trained model BERT-base-Chinese, which contains 110 million parameters. This extensive parameterization enhances semantic information capture, mitigating potential semantic biases arising from discrepancies between pre-training corpora and task-specific texts. Second, we focused on downstream task adaptation, comprising fine-tuning and classifier training. Fine-tuning typically retrains the pre-trained model on domain-specific corpora to optimize task performance. However, we decided to forgo this process given the high linguistic consistency between government subsidy documents and BERT's original training corpus, coupled with our relatively limited training sample size. Consequently, our primary methodology centered on developing a text classifier utilizing BERT's output vectors. Specifically, a linear classification layer first computed the scores (s) for BERT-generated text representation vectors (c) across categories, followed by the transformation of these scores into probability distributions via the softmax function. For binary classification tasks, the predicted probability for Category 0 was formalized as follows:

Drawing on Liu et al. (2023), we employed BERT to identify digital subsidies within government grants, establishing direct measurement metrics. First, we performed data preprocessing. We collected over 610,000 government subsidy projects from 2007 to 2023 and matched the corresponding subsidy projects to the relevant listed companies. Due to the large size of the original dataset, the substantial noise present in the corpus may hinder the model's ability to understand semantic relationships during the subsequent model training phase, reducing the model’s classification performance. Therefore, data cleaning operations were conducted, encompassing removing redundant columns from the tables, eliminating special characters and stop words, minimizing data noise, and converting all text to UTF-8 encoding. Using stratified sampling, we randomly selected 5,000 government subsidy projects. Of these, 4,000 records were used to form the training set for pattern recognition, 500 records were used for hyperparameter tuning in the validation set, and 500 records were used for generalization ability evaluation in the test set. The ratio of the training set, validation set, and test set was 8:1:1, ensuring effective data allocation for model training, tuning, and evaluation. To enhance the model's generalization ability, no data overlap was allowed between the training and test sets. The experimental environment encompassed the following: the operating system Windows 10 64-bit; integrated development environment (IDE) PyCharm 2025.1.1; development language Python 3.9.7; and deep learning framework Pytorch 1.11.0.

Next, we used the BERT model to identify digital subsidies in government grants. First, we prepared the pre-trained model. For the Chinese dataset, the embedding layer used the BERT-base-chinese model. Second, we fine-tuned and trained the model. The BERT-base-chinese model has been pre-trained on Chinese text and has learned the contextual features of the Chinese language from a large-scale Chinese corpus. Hence, it is better suited for expressing and understanding Chinese semantics. Therefore, the pre-trained model can be directly used for training without the need for additional fine-tuning steps. Third, we classified the training data. Based on the definition of government digital subsidies, we manually annotated 5,000 randomly selected government subsidy projects to ensure the accurate identification of digital subsidies. The project was classified as positive (digital subsidy) if it satisfies one of the following conditions: "Digital technology development" or "Digital transformation application." The specific keywords are listed in Appendix Table A1. Each subsidy entry was independently annotated by three experts in the field of digital economy. Any discrepancies in the annotations were discussed and confirmed. The annotation criteria included information such as the subsidy amount and project name. Additionally, the context of each subsidy entry was carefully reviewed to ensure that the model can accurately identify and distinguish digital subsidies from other types of subsidies. Table 1 shows an example of the representative samples from the listed company government subsidy dataset.

Example of government subsidy dataset for listed companies.

The main parameters of the BERT model are shown in Table 2.

The optimization strategy used the BERT-specific Bert Adam optimizer. The model learning rate was set to 2E-5. Further, a dynamic learning rate strategy was applied for learning rate decay, with a weight_decay of 1E-3. The confusion matrix on the test set is shown in Fig. 2, while the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) curve is presented in Fig. 3.

To further validate the model's performance in identifying minority groups, we conducted a specific evaluation on digital subsidy information, reflecting the results by comparing various data metrics obtained from different models on the task. We utilized four commonly used evaluation metrics in text classification tasks: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score. The results show an accuracy of 0.99, precision of 0.99, recall of 0.99, and an F1 score of 0.99. The model's high recall rate indicates strong performance in recognizing digital subsidy information, especially in identifying minority groups. This demonstrates that the model can effectively recognize and accurately label digital subsidy projects. Finally, the trained model was applied to unlabeled subsidy projects to classify them as digital subsidies.1 The total amount of government digital subsidies received by each firm each year was calculated by summing the amounts under all relevant sub-categories. The natural logarithm of this amount represents the government digital subsidy, denoted as Subsidy. For robustness, we employed three proxy variables for government digital subsidies: the ratio of the subsidy amount to operating revenue (Subsidy1), the number of times a firm receives digital subsidies per year (Subsidy2), and a dummy variable indicating whether a firm has received any government digital subsidy (Subsidy3).

Control variablesDrawing on extant research (Shao et al., 2023; Tao et al., 2025), this study selected several factors that may influence corporate digital technology innovation: Firm age (Age), measured as the logarithm of one plus the years since listing. A longer establishment period indicating greater experience in adapting to complex changes and fundamental capacity for digital innovation. Leverage ratio (Lev), calculated as total liabilities to total assets at the end of the period. Lower ratios suggest greater potential allocation of assets to digital innovation needs. Tangible asset ratio (Tang), measured as the sum of net fixed assets and net inventory to total assets. Higher ratios indicate greater fixed and sunk costs, reduced organizational flexibility for strategic transformation, and potentially weaker willingness and capability to invest in emerging digital technologies. Return on equity (ROE), calculated as net profit to average shareholders' equity. Higher values reflect stronger operational efficiency and capital management capabilities that motivate digital innovation. Tobin's Q (Tobin), measured as market value to total assets. Cash flow ratio (Cash), calculated as operating cash flow to total liabilities. In addition to firm-level control variables, we incorporated industry-level controls, including industry competition intensity (HHI), industry scale (Size), and average firm age within the industry (Ave). Industry competition intensity was measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), calculated as the sum of squared market shares of operating revenue relative to total industry operating revenue, reflecting competitive pressures. Industry scale was represented by the total number of firms within each sector. The aggregate industry resources and policy support intensity may vary with market size. The average firm age within each industry captures the mean establishment duration of companies operating in that sector.

Econometric model specificationPanel benchmark regression modelWe estimate the following two-way fixed effects model:

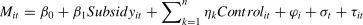

where i denotes firms and t represents years. Digtechit measures the level of digital technology innovation for the firm i in year t. Subsidyitcaptures the intensity of government digital subsidies received by the firm i in year t. α1 is our primary coefficient of interest, reflecting the impact of government digital subsidies on corporate digital technology innovation. Controlit represents the set of control variables that may influence digital technology innovation, while n is the number of control variables. The model incorporates firm (μi) and time fixed effects (γt) to account for unobserved heterogeneity at both the firm-specific level and temporal trends, respectively, with εit denoting the random disturbance term. All empirical analyses employ robust standard errors clustered at the firm level to address potential heteroskedasticity and within-firm correlation.Mechanism testing modelFirst, following (Jiang, 2022), we examined the impact of government digital subsidies on the mechanism variables using the following model:

where Mit represents various mechanism variables, including financing constraints, R&D willingness, and digital strategic deployment. Controlit is the set of control variables consistent with the baseline regression model. β0 is a constant term and β1 is coefficient to be estimated. The model incorporates firm (φi) and time fixed effects (σt) to account for unobserved heterogeneity at both the firm-specific level and temporal trends, respectively, with τit denoting the random disturbance term.Second, drawing on Alesina and Zhuravskaya 2011, we controlled for the mechanism variables based on the baseline regression. If the mechanism indeed explains how government subsidies promote digital technology innovation, the coefficient or significance of the core explanatory variable (Subsidy) should change after controlling for the mechanism variables. We used the following specification:

where ρ represents the coefficient of the mechanism variables. Controlit is the set of control variables consistent with the baseline regression model. δ0 is a constant term and δ1 is coefficient to be estimated. The model incorporates firm (ωi) and time fixed effects (ϑt) to account for unobserved heterogeneity at both the firm-specific level and temporal trends, respectively, with ∈it denoting the random disturbance term. However, mediation models may suffer from endogeneity issues when identifying causal mechanisms. Hence, we supplemented the mediation analysis with Sobel tests and Bootstrap resampling tests (500 repetitions) to enhance the robustness of mediation effect estimates and reliability of conclusions.Descriptive statisticsTable 3 reports the descriptive statistics. First, digital technology innovation (Digtech) shows a mean value of 0.7367 with a standard deviation of 1.2227. This indicates that the overall level of digital innovation output among Chinese listed firms remains relatively modest, while exhibiting substantial variation across both firms and years. Second, the government digital subsidy measure (Subsidy) displays a mean of 3.5486 and standard deviation of 6.1323. That is, while the scale of government digital subsidies can be increased, substantial heterogeneity exists in subsidy allocation across different firms.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 4 presents the estimation results of the impact of government digital subsidies on corporate digital innovation. Column (1) reports the baseline estimates without control variables or fixed effects. Column (2) introduces firm and year fixed effects, while Column (3) incorporates control variables without fixed effects. Column (4) considers both control variables and dual fixed effects. The results exhibit remarkable consistency: The coefficient of government digital subsidies (Subsidy) remains positive and statistically significant at the 1 % level across all specifications. Thus, government digital subsidies significantly promote corporate digital technology innovation, with no substantial changes in coefficient magnitude or statistical significance observed between alternative model configurations. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Benchmark regression results.

Note: Standard errors in parentheses; ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively. This notation applies to subsequent tables.

Our results may suffer from endogeneity concerns arising from omitted variables and reverse causality. On the one hand, firms with higher levels of digital innovation typically possess stronger innovation capabilities and a more solid foundation for digital transformation, increasing their likelihood of receiving government digital subsidies. On the other hand, government subsidies are not entirely neutral and tend to favor firms that are already active in digital innovation. To address these issues, we construct two distinct sets of instrumental variables.

The first set is constructed following Lewbel’s (1997) approach. Specifically, we calculate the cubic transformation of the deviation between firm-level annual digital subsidies and their industry-year means (IV1=[Subsidyit−IndustrySubsidyjt]3). This method leverages heteroskedasticity in the error terms to construct statistically valid instruments without relying on external variables. This instrumental variable reflects the degree of deviation of digital subsidies of firms relative to their peers, and can characterize the inherent differences in the ability of firms to obtain subsidies. Taking the cube further amplifies the heterogeneity between individuals and enhances its correlation with government digital subsidies. The deviation of corporate subsidies is uncorrelated with the structural error term in digital innovation, meeting the exogeneity requirement.

Next, we construct the second set of instrumental variables. First, we construct the second instrumental variable (IV2) as the industry-average government digital subsidy excluding the focal firm. The industry-level mean subsidy strongly correlates with governmental support for digital innovation, reflecting the policy prioritization of digital transformation initiatives. The correlation condition is satisfied since firms' subsidy allocations inherently relate to such policy intensity. Simultaneously, the exogeneity condition holds because peers' industry-average subsidies have no direct bearing on a specific firm's digital innovation outcomes. Second, following Yang et al. (2015), a second instrumental variable (IV3) is constructed as the product of the deviation of a firm's digital technology innovation level from the average level of all firms and deviation of the firm's government digital subsidies from the average subsidies amount. We estimate these instrumental variables using a two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression.

Table 5 presents the 2SLS estimates. Columns (1)-(2) report the results using IV1, while Columns (3)-(4) jointly employ IV2 and IV3. All specifications pass identification and weak IV tests. The regression results remain consistent with those of the baseline model, indicating that the instrumental variables employed here are both valid and appropriate. The Hansen J-test (p=0.6074) confirms instrument exogeneity. Crucially, subsidy coefficients remain positive and significant, reinforcing our baseline findings.

Regression results using instrumental variable approach.

Note: p-values are reported in square brackets. Critical values at the 10 % significance level from the Stock–Yogo test are reported in curly brackets.

Crucially, government digital subsidies may not be entirely exogenous. For instance, firms with stronger digital innovation capabilities may be more likely to receive subsidies. Hence, a potential sample selection bias may exist in our study. To address this issue, the Heckman two-step method is employed.

In the first stage, a Probit model is estimated using a binary variable indicating whether a firm received a government digital subsidy (1 if received and 0 otherwise). The industry-level average of government digital subsidies (Average) is included as an exclusion restriction in the model. Based on this estimation, the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) is calculated.

In the second stage, IMR is added as a control variable to the baseline regression model to correct for potential sample selection bias. The first-stage regression results are presented in Column (1) of Table 6. The coefficient of Average is significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating a strong correlation. The second-stage regression results are shown in Column (2) of Table 6. The coefficient of IMR is statistically significant at the 1 % level, confirming the presence of non-negligible selection bias. Additionally, the coefficient of Subsidy remains significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Results of endogeneity problem treatment.

Propensity score matching (PSM) is an econometric method used to mitigate endogeneity problems arising from selection bias. By matching individuals with similar observable characteristics, PSM ensures that the treatment and control groups do not significantly differ in their likelihood of receiving the treatment. First, we estimate propensity scores using all predefined control variables. Second, we perform 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching based on these scores. As shown in Column (3) of Table 6, the coefficient of subsidy remains positive and statistically significant, consistent with baseline estimates.

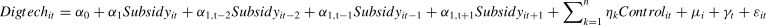

Dynamic effect testThe implementation of subsidy policies may affect corporate innovation behavior. Before receiving the subsidy, companies may have already begun relevant technological planning or innovation activities to meet the requirements of the subsidy policy. If this behavior is not considered, it could lead to endogeneity bias. To further verify the effect of digital subsidy policies and explore whether it exhibits anticipation (e.g., whether firms engage in advance planning and innovation before the subsidy announcement) and lagged effects (e.g., whether government subsidies have long-term impacts), we introduce a dynamic effect test. Specifically, we add lagged and lead terms of the subsidy to examine the anticipatory and long-term effects of the subsidy policy on firms' digital technology innovation. Concretely, based on the baseline model, we include one- (Subsidyit−1) and two-period lagged (Subsidyit−2) government subsidies, as well as a one-period lead government subsidy (Subsidyit+1) to investigate the dynamic effects of the subsidy policy on firms' digital technology innovation. The specific model is specified as follows:

where Subsidyit−1 and Subsidyit−2 represent the long-term effects of the one- and two-period lagged subsidies, respectively; Subsidyit+1represents the anticipation effect of the one-period lead subsidy; and α1,t−1, α1,t−2, and α1,t+1 are their respective coefficients. Other settings are consistent with the baseline regression. The results in Column (4) of Table 4 indicate that the coefficient of the one-period lead government digital subsidy is insignificant. Therefore, the government digital subsidy policy did not anticipate or precipitate firms' strategic planning. However, the coefficient of the one-period lagged government digital subsidy is significantly positive at the 10 % level, while the two-period lagged term is insignificant. This suggests the presence of dynamic effects in government digital subsidies. In summary, the impact of government digital subsidies on firms' digital technology innovation exhibits a significant one-period lagged effect. Firms primarily respond to the policies rather than making proactive adjustments and innovations based on expectations of future policy implementation.Robustness testsWe perform further robustness tests. First, we further control for the impact of digital market competition. To more comprehensively reflect the competitive environment in which firms operate under the digital economy, we further introduce urban-level digital infrastructure indicators, thereby more precisely controlling the external environment's impact on corporate digital technology innovation. Following the literature, we introduce two indicators: "the number of digital platform firms" and "number of base stations." First, we define the number of digital platform firms as the number of new firms in the information transmission and research technology service industries located in the city where the company operates, denoted as Companies. This indicator reflects the degree of digital development in the city and digital characteristics of market competition. Second, we define the number of base stations as the number of communication base stations in the city where the company is located, denoted as Stations. The number of base stations is an important measure of a city's digital infrastructure development. It reflects the city's internet coverage and penetration of mobile internet, which in turn affects the conditions for firms to engage in digital innovation in that region. After controlling for the above variables, the results in Column (1) of Table 7 indicate that the size and significance of the government digital subsidy coefficient are consistent with the baseline regression, demonstrating clear robustness. Thus, the policy effect is robust across different digital competition environments.

Robustness Tests.

Second, we use alternative proxy variables. We use the ratio of digital subsidies to operating revenue (Subsidy1), the number of times a firm received digital subsidies (Subsidy2), and a dummy variable indicating whether the firm received any digital subsidies (Subsidy3) as alternative explanatory variables for government digital subsidies. As shown in Columns (2) to (4) of Table 7, the coefficients of the key explanatory variables remain significantly positive, consistent with the baseline regression results.

Third, we incorporate fixed effect and clustering adjustments. First, to account for unobservable macro-level systematic factors that vary annually across industries and cities, we augment the baseline regression by incorporating industry- and city-year interaction fixed effects. As reported in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 7, the coefficient of the key explanatory variable remains significantly positive. Second, we adjust the clustering level. We cluster standard errors at the city and provincial levels, respectively. The results in Columns (7) and (8) of Table 7 indicate that regardless of the clustering level, the coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive at the 1 % level.

Fourth, we consider policy confounding controls.2 To further validate the robustness of the impact of government digital subsidies on digital technology innovation, we follow the approach of previous studies and control for the influence of major strategic policies, such as the “Four Trillion Stimulus Plan,” “Made in China 2025,” and “Strategic Emerging Industries.” The results show that, even after individually or jointly controlling for these policy interventions, the positive effect of government digitalization subsidies on digital technology innovation remains statistically significant, thereby reinforcing the robustness of our main findings.

Finally, we use sample restrictions.3 (i) First, we exclude the periods of major economic shocks, such as the global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we exclude observations from these specific periods. (ii) We exclude firms located in top-tier cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. These cities are characterized by higher levels of economic development and more advanced digital infrastructure. Hence, they tend to attract firms with stronger digital transformation and innovation capabilities. To assess the generalizability of the effect of government digital subsidies and reduce the influence of potential outliers, we exclude firms headquartered in these four cities and re-estimate the models. The results remain consistent with the baseline findings.

Placebo testWe conduct a placebo test to further validate the robustness of our baseline regression results. Specifically, 500 random samplings are performed to randomly generate treatment groups and we examine whether the corresponding estimated coefficients remain significant. If these results differ from the actual regression results, it can effectively rule out the interference of other random factors. The placebo test results are presented in Fig. 4. The estimated coefficients from the random samples are mostly distributed around zero. Thus, in the absence of policy intervention, the coefficients do not significantly deviate from zero. Therefore, the baseline regression results are relatively robust and the effect of government digitalization subsidies is not driven by random factors.

Mechanism and further analysesMechanism analysisAlleviating financing constraintsGovernment digital subsidies can directly enhance firms' cash flow, effectively alleviating the external financial constraints faced by firms during digital transformation. Moreover, digital subsidies also serve a signaling function. When firms are supported by digital subsidies, financial institutions are more likely to form positive expectations when assessing the uncertainties of firms’ digital technology innovation. This can enhance their recognition of firms' creditworthiness and improve the firms' debt financing environment. Drawing on financial constraint data from the CSMAR database, we use the SA index as a proxy variable for financial constraints, denoted as Financial constraints. The results are shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8. Column (1) indicates that government digital subsidies have a significantly negative impact on firms' financial constraints. Thus, subsidies indeed alleviate financing constraints. Further, after controlling for firms' financial constraints, Column (2) shows that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable increases compared to the baseline regression result (0.0032) and remains significant at the 1 % level, suggesting that government digital subsidies promote firms’ digital technology innovation by alleviating financial constraints.

Mechanism Test 1.

Government digital subsidies, through both income and substitution effects, increase firms’ disposable funds and lower unit R&D costs, effectively reducing financial pressures and uncertainties in the R&D process. This can enhance firms' willingness to engage in R&D, and thus, promote digital technology innovation. Following Han et al. (2024), we use the logarithm of firms’ R&D investment amount from the CSMAR database as a proxy variable for R&D willingness, denoted as R&D willingness. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8 report the mechanism test results for R&D willingness. Column (3) shows that government digital subsidies have a significantly positive effect on firms' R&D willingness at the 1 % level. After further controlling R&D willingness, Column (4) shows that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable slightly decreases compared to the baseline regression and its significance remains unchanged. Thus, government digital subsidies enhance firms' digital technology innovation by increasing their R&D willingness.

Strengthening digital strategic deploymentManagement's focus on digitalization and strategic deployment can guide firms' digital innovation direction (Liu et al., 2020). Following Wu et al. (2021), we first construct a digital feature keyword dictionary based on national-level digital economy policy documents, identifying keywords related to both foundational digital technologies and digital application practices. Then, using Python, we identify and match the frequency of digital feature keywords in the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) sections of firms' annual reports, forming an initial indicator of firms’ digital deployment. Finally, the logarithm of the frequency of digital feature keywords identified for each firm in each year is used as the proxy variable for managerial digital strategy deployment, denoted as Digital strategy. The results are presented in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 8. Government digital subsidies have a significantly positive effect on digital strategy deployment at the 1 % level. After controlling digital strategy deployment, the effect of subsidies on innovation remains significantly positive at the 1 % level, with the coefficient slightly decreasing to 0.0031 compared to the baseline coefficient. Thus, government digital subsidies can positively impact firms’ digital technology innovation by strengthening digital strategy deployment.

In practice, expanding the internal demand for digital talent and increasing the frequency of strategic technology alliances are critical measures that effectively reflect the actual implementation of a firm's digital strategy deployment. They also indicate the firm's responsiveness to government digital subsidies. Specifically, digital transformation requires firms to possess advanced technological capabilities, innovative thinking, and the ability to integrate cross-domain knowledge. Consequently, firms need to reshape their internal structures to achieve strategic objectives, particularly regarding human capital and job role adjustments (Moncada et al., 2025). The literature indicates that employees with higher education possess distinct advantages in learning and implementing new technologies (Bartel & Lichtenberg, 1987). Therefore, by cultivating talent with cutting-edge digital technical knowledge, firms can more effectively drive technological innovation and market adaptation, thereby supporting the execution of their digital strategies. Digital strategy deployment also extends beyond internal restructuring. It is a vital mechanism for firms to acquire technological capabilities and innovation resources through external collaboration. The frequency of strategic technology alliances reflects a firm's proactiveness and systematic approach in external technological synergy, demonstrating its strategic orientation towards resource integration within digital strategy deployment (Teece, 1992). Collectively, the internal demand for digital talent and formation of strategic technology alliances constitute the dual pathways of digital strategy deployment: that is, these represent internal reorganization and external collaboration. These pathways serve as the critical bridge enabling firms to translate strategic cognition into concrete action.

To further validate the impact mechanism of digital strategy deployment on corporate digital technology innovation from a practical perspective, this study first introduces digital labor demand as a mediating variable. Firm demand for digital talent is measured using the number of AI-related positions posted in their job openings, denoted as Digital talent. To capture information from China's recruitment market, job posting data are scraped from major Chinese recruitment platforms, including 51job, BOSS Zhipin, Zhaopin, Liepin, Lagou, and Kanzhun. Following Yao et al. (2024), positions are identified as AI-related if their titles or descriptions contained keywords associated with AI. The count of AI-related positions is then aggregated at the firm-year level. Given that significant recruitment for AI positions primarily commenced in 2016, the data for the Digital talent variable spans the period 2016–2023. The results, presented in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, show that the effect of digital subsidies on digital labor demand is significantly positive at the 5 % level. Further, the subsidy coefficient decreases after controlling the Digital talent variable. Thus, digital subsidies significantly stimulate firms' demand for talent possessing cutting-edge technical knowledge, thereby enhancing internal high-skilled human capital. The influx of such talent enables firms to intensify R&D efforts in fields like AI, big data, and cloud computing, facilitating technological breakthroughs and the implementation of market applications.

Mechanism Test 2.

Then, we introduce strategic technology alliances as a mediating variable. We define strategic technology alliances as the frequency of strategic cooperation between sampled firms and other technology firms, reflecting the intensity of their technological-related strategic collaborations, denoted as Strategic alliance. First, based on public information from authoritative news media such as company announcements, Tencent, Sina, and others, we compile specific announcement titles, partnering companies, and the content of strategic cooperation. Second, by matching keywords related to technology with the details of the strategic alliances, we filter projects where companies engage in strategic technology alliances. Finally, we aggregate the data at the firm-year level to obtain the number of strategic technology alliances for each firm. The results are shown in Columns (3) and (4) in Table 9. Digital subsidies have a significantly positive impact on strategic technology alliances at the 1 % level. After controlling for the technology strategic alliance variable, the subsidy coefficient remains significantly positive at the 1 % level. Thus, government digital subsidies can positively influence corporate digital technology innovation by promoting strategic technology alliances.

Furthermore, recognizing that the extent of corporate digital strategic deployment may vary with CEOs' IT expertise and level of AI technology adoption, this study examines these differential effects. Executives' educational and professional backgrounds directly shape their understanding of technological trends, comprehension of policy instruments, and willingness to embrace digital strategies (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Moreover, according to the theory of digital leadership (Bassellier et al., 2003), CEOs with an IT background are better able to identify the synergistic value brought by digital technologies and optimize resource allocation through strategic decision-making. While driving the firm’s digital transformation, these CEOs not only possess keen insight into emerging technologies but also effectively integrate technological resources and promote cross-departmental collaboration, thereby enhancing the company's overall digital capabilities (Armstrong et al., 1999; Wrede et al., 2020). Therefore, CEOs with an IT background can leverage digital technologies to facilitate data flow between different departments and business systems, promoting information sharing and resource integration, accelerating the advancement of digital transformation (Cai et al., 2024), and strengthening the company's digital strategy deployment. We identify IT expertise through keyword screening of CEOs' backgrounds in A-share listed companies based on three criteria: IT-related educational qualifications, emerging technology certifications, and IT industry experience. Then, the full sample is divided into IT- and non-IT-background subgroups. Then, we refer to Ling et al. (2025) and perform group regression. As shown in Columns (1)-(2) in Table 10, digital strategic deployment significantly enhances corporate digital technology innovation only in firms with IT-background CEOs. In digital innovation contexts, technologically proficient managers are paramount for success, requiring substantial digital knowledge and technical experience to drive innovation.

Heterogeneity Analysis of Digital Strategic Deployment on Digital Technology Innovation.

Simultaneously, AI adoption signifies advanced digital infrastructure, data governance capabilities, and algorithmic competencies. Such foundational strengths compel systematic strategic planning, thereby deepening digital deployment. Following He et al. (2020), we measure AI adoption levels using the value of machinery and equipment, with median-based grouping. The results in Columns (3)-(4) in Table 10 reveal that digital strategic deployment only significantly promotes digital innovation in high-AI-adoption firms. This demonstrates AI's role as an organizational amplifier or catalyst that enhances the transformation efficiency of government digital subsidies into innovation outcomes.

Heterogeneity analysisFirm characteristicsWe examine the heterogeneous effects of government digital subsidies across three firm characteristics: ownership type, lifecycle stage, and size.

First, ownership type. Systematic differences in resource acquisition approaches, operational objectives, risk preferences, and government dependency exist across firms with distinct ownership types. To examine this heterogeneity, we categorize listed firms into state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-SOEs based on their administrative affiliations. Columns (1)-(2) of Table 11 present the regression results. Digital subsidies significantly positive influence SOEs’ digital innovation levels at the 10 % significance level, whereas non-SOEs exhibit an even stronger significant positive effect. This divergence aligns with the institutional realities: SOEs benefit from resource allocation privileges, robust financing channels, and stable government backing. Thus, they may prioritize compliance-driven innovation that demonstrates low marginal responsiveness to fiscal incentives. Conversely, non-SOEs face intensified market competition and financing constraints. Subsidies not only alleviate R&D funding gaps but also enhance capital market credibility through signaling effects, thereby stimulating stronger innovation incentives.

Heterogeneity Test Results Based on Firm Characteristics.

Second, firm lifecycle stage. Firms at different lifecycle stages exhibit distinct capacities for innovation risk tolerance and resource absorption, which may consequently moderate the effectiveness of government digital subsidies. To identify differentiated policy impact pathways, this study incorporates lifecycle heterogeneity variables following Li and Li’s (2012) methodology, categorizing firms into growth, maturity, and decline stage cohorts. As shown in Columns (3)-(5) of Table 11, digital subsidies demonstrate the strongest innovation-enhancing effect on growth stage firms and statistically insignificant effects on decline stage firms. Growth stage firms are typically in market expansion phases, where government subsidies alleviate capital constraints, and enable accelerated technical iterations and digital convergence. Their flat organizational structures and short decision-making chains facilitate the rapid conversion of subsidies into tangible technological investments, driving cross-departmental information system integration and intelligent upgrades. Conversely, innovation activities in maturity stage firms often follow established procedures. Hence, the subsidies primarily support existing R&D systems rather than incentives for disruptive digital transformation. Meanwhile, decline stage firms often face financial distress and organizational rigidity, Even when they receive government subsidies, they lack the capacity to effectively utilize and transform them into technological innovations.

Finally, firm size. Firm size critically shapes resource endowments, organizational structures, and policy responsiveness. Using median total assets as the threshold, we bifurcate the sample into small and large firms (Columns (6)-(7), Table 11). Small-scale firms demonstrate significant innovation gains from subsidies (α₁=0.0028***, p<0.01), whereas large-scale firms show no meaningful response. This dichotomy arises because small firms universally face resource constraints, particularly relying on external support for funding, talent, and technological infrastructure. This limits their capacity for independent high-intensity technological innovation. Government digital subsidies provide these firms with critical financial resources that not only alleviate financing constraints and R&D cost pressures but also enhance the feasibility and motivation for innovation investment, thereby creating essential conditions for digital innovation. Conversely, large firms possess more mature R&D systems, financial reserves, and external financing channels, with innovation activities predominantly driven by internal resources. This self-sufficiency fosters a degree of innovation complacency and path dependence. While digital subsidies offer direct financial support to large firms, their propensity to maintain established technological trajectories and weaker responsiveness to fiscal incentives results in statistically insignificant digital innovation outcomes.

Regional characteristicsNext, we examine the heterogeneity due to two regional characteristics: marketization levels and digital economy policy intensity.

First, regional marketization level. The institutional environment fundamentally shapes firms' responsiveness to policy incentives and innovation activities. Regional marketization levels directly influence resource allocation efficiency, potentially moderating digital subsidy effectiveness. Following Fan et al. (2011), we construct a marketization index and bifurcate regions into high/low marketization groups using median values (Columns (1)-(2), Table 12). The results indicate that digital subsidies significantly enhance innovation in high-marketization regions but have no meaningful effects in low-marketization regions. This divergence stems from institutional dynamics: Developed markets provide robust technical collaboration platforms, high talent mobility, and efficient commercialization mechanisms, amplifying subsidy externalities through optimized innovation resource allocation. Conversely, low-marketization regions suffer from excessive government intervention and rigid market mechanisms. Here, subsidy funds are prone to rent-seeking or misallocation, distorting policy transmission and undermining innovation outcomes.

Heterogeneity Test Results Based on Regional Characteristics.

Second, regional digital economy policy intensity. Digital economy policies serve as critical external drivers for corporate technological innovation. Different regions implement digital economy policies with varying intensities, reflecting differences in governments' levels of digital focus and support for the digital economy. This can influence the impact of government digital subsidies on firms' innovation activities. To assess how regional policy intensity moderates subsidy effects, we adopt Tao and Ding's (2022) methodology, measuring policy intensity through keyword frequency ratios in municipal government work reports. Bifurcating the regions by mean policy intensity (Columns (3)-(4), Table 12), we find significant innovation gains in high-intensity regions versus null effects in low-intensity areas. Thus, government digital subsidies and digital economy policies can form a strong synergy, jointly promoting firms' digital innovation. High-intensity regions establish comprehensive digital infrastructure, systematic industry ecosystems, and mature data markets, creating an innovation-friendly environment where subsidized firms effectively integrate fiscal support with local policy resources. Such synergy accelerates inter-firm knowledge spillovers and R&D commitment. Conversely, low-intensity regions exhibit fragmented policy frameworks and inefficient subsidy dissemination mechanisms, where firms face heightened uncertainty and transaction costs in utilizing subsidies, ultimately diluting innovation incentives.

Further analysis: cross-domain innovation quantity and qualityDistinct from conventional or general cross-domain innovation, corporate cross-domain digital innovation emphasizes the integration of digital technologies with non-digital fields. This is characterized by technological boundary-breaking composite innovations that entail heightened uncertainty and risks. The innovations are particularly susceptible to government digital support. Digital products, defined as new offerings incorporating digital technologies, encompass both hybrid (digital-physical) and purely digital innovations (Boudreau, 2012). While theoretical analyses suggest that government digital subsidies incentivize digital innovation, empirical evidence indicates that these subsidies may also induce strategic innovation behaviors (Chen & Zhang, 2019). Thus, we need to examine how subsidies affect both the quantity and quality of cross-domain digital innovations in traditional firms.

To examine corporate digital innovation behaviors, drawing on Tao et al. (2025), we identify listed firms' digital invention patents and classify them into two categories based on IPC codes: Fusiontech (patents combining digital and non-digital IPC codes) and Puretech (patents containing only digital IPC codes). Innovation quality (Quality) is measured using average patent citations. To examine the impact of digital subsidies on digital innovation quality, three metrics are employed: average patent citations (Quality1), count of highly cited digital patents (Quality2), and digital patent knowledge breadth (Quality3). Highly cited digital patents are defined as those ranking in the top 1 % of annual citations within their respective industries. Quality2 is measured by aggregating such patents annually. Patent knowledge breadth captures quality through the complexity and diversity of technological knowledge, effectively mitigating limitations of citation-based metrics. Following Akcigit et al. (2016), we compute this indicator using a weighted Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) approach based on IPC subgroup classifications after identifying digital innovation patents. Greater knowledge breadth reflects higher dispersion across patent subgroups, potentially indicating superior innovation quality.

The results in Columns (1)-(2) of Table 13 reveal significantly positive coefficients for digital subsidies. Columns (3) to (5) show the regression results with digital innovation quality as the explained variable. Digital subsidies have no significant impact on cited patents, while the impact on the breadth of digital patent knowledge is significantly negative. Thus, government digital subsidies effectively stimulate the proliferation of both fusion and pure digital patents, while they negatively affect the quality of digital innovation. This pattern reflects a tendency toward strategic and policy-responsive innovation behaviors among firms. Specifically, firms focus more on the quantity rather than the substantive quality of technological advancements in response to external policy incentives. The underlying rationale lies in firms' prioritization of "digital+" labeled projects under national strategic imperatives, which incentivizes quantity-driven compliance over quality enhancement. Specifically, subsidies lower entry costs for experimental cross-domain initiatives, enabling firms to diversify technological portfolios by bridging existing capabilities with digital domains, thereby driving quantitative growth. However, sustained quality improvement requires the deep integration of heterogeneous technologies. This capability is constrained by insufficient internal technical synergy, specialized talent, and cross-industry knowledge accumulation. Despite initial funding support, the lack of these foundational capacities traps innovation at superficial integration levels, preventing high-quality breakthroughs and even suppressing the quality of digital innovation.

Further Analysis Results.