This study explored the impact of green innovations on a firm’s financial performance over time, considering the short-term, transitional and long-term effects. Using data from 4291 Chinese A-share listed companies between 2004 and 2021, we applied a novel long-difference multi-level fixed-effects approach to gain new insights. The findings suggest that the impact of green innovation on return on assets (ROA) is contingent upon the type of innovation, time frame and market conditions. During the transitional phase, the overall level of green innovation and its quality positively influence ROA. However, in the long run, the quantity of green innovation may adversely affect ROA. In addition, leverage emerges as a significant determinant of ROA across firms. Quantile analysis further revealed that green innovation benefits firms with lower ROA but may negatively impact those with higher ROA. These results offer valuable guidance for policymakers and corporate strategists seeking to optimise green innovation strategies for sustainable financial performance.

Amid growing environmental concerns, green innovation has become a vital strategy for companies aiming to achieve sustainable development while maintaining economic growth. This approach, which involves the adoption of eco-friendly technologies and practices, has gained considerable traction globally, particularly in nations with rapid industrialisation, such as China (Zhu & Tan, 2022). China’s shift towards green innovation is crucial for sustainable economic progress as the world’s largest manufacturing centre and a major source of global greenhouse gas emissions (Urban, 2015). Therefore, understanding the impact of green innovation on corporate financial performance, particularly through metrics like ROA (Return on Assets), is pivotal for determining whether sustainable practices can be harmonised with financial performance (Farza et al., 2021). ROA is chosen over EBITDA margin and ROE as it offers a holistic view of a company’s asset utilisation and profitability. It is beneficial for industry comparisons and long-term financial health assessments. This study investigated the association between green innovation and ROA in Chinese companies, providing valuable insights for investors, managers and policymakers on integrating sustainability with profitability.

The motivation for this study is rooted in several key propositions. First, Chinese companies face dual pressures to balance environmental sustainability with the maintenance of competitive financial performance. In recent years, these pressures have intensified, driven by China’s ambitious commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 and the implementation of increasingly stringent government regulations on pollution control (Chen et al., 2018). As a result, businesses are compelled to adopt innovative strategies that align with environmental goals while ensuring economic viability, thereby creating a complex and dynamic landscape for corporate decision-making. However, despite the regulatory push and the growing emphasis on corporate social responsibility, the financial implications of green innovation remain unclear, particularly in terms of its influence on profitability indicators, such as ROA. While previous studies have mainly employed static approaches to measure the financial impact of green innovation, we argue that a more dynamic perspective is necessary (Huang et al., 2022; Vasileiou et al., 2022; N.M. Ha et al., 2024).

Second, the association between green innovation and financial performance is a subject of considerable debate among scholars, practitioners and policymakers. While some argue that green innovation enhances financial performance through various positive channels, others contend that it may impede profitability owing to certain negative factors (Ha et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2022; Vasileiou et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). First, the implementation of green technologies often leads to reduced energy consumption and resource utilisation (Khajehei, 2015). For example, the adoption of energy-efficient machinery can lower utility bills, directly improving the bottom line (Mecrow & Jack, 2008). Green patents, which pertain to environmentally friendly technologies and innovations, are becoming increasingly important for A-share companies in China, particularly as the country prioritises sustainable development and environmental protection. These patents are valued for their potential to increase revenue, reduce costs or strengthen market competitiveness, typically evaluated using cost, market or income approaches. Companies holding green patents often enjoy government incentives, including subsidies, tax breaks and expedited patent approvals, aligning with China’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality. Green innovations in waste management can lower disposal costs and generate revenue through recycling (Meriç et al., 2018). Growing eco-conscious consumer demand supports premium pricing (Campbell et al., 2015), enabling market expansion and sales growth (N.M. Ha et al., 2024). Firms can gain a competitive edge through product differentiation (Dangelico, 2016), whereas regulatory compliance reduces legal risks and fines (Gupta et al., 2019). Government incentives, such as grants and tax credits, enhance financial stability (Zhang et al., 2020). Strong environmental credentials attract investors, boosting capital inflow and stock valuations (Delmas & Lim, 2016). Sustainability improves employee retention and reduces turnover costs. Green innovations also mitigate environmental risks, thereby lowering legal liabilities and reputational damage (Dögl & Holtbrügge, 2014). Sustainable sourcing stabilises supply chains, whereas pioneering green technologies open opportunities for licensing and industrial leadership (Lam et al., 2015).

Green innovation often requires substantial upfront investment in research and development (R&D), equipment and facility upgrades, straining financial resources (Welfens et al., 2016). Returns may be uncertain or long-term, impacting short-term performance and shareholder value (Chariri et al., 2018). Higher costs of eco-friendly materials and compliance expenses can further impact profitability (Almeida et al., 2017). Limited consumer willingness to pay a premium may reduce sales and margins (Harms & Linton, 2016), whereas competition from non-green firms can erode market share (Sharma, 2017). Furthermore, unproven green technologies may lead to operational disruptions and additional costs (Suwanapingkarl et al., 2015). Regulatory inconsistencies complicate planning, particularly in international markets (Bagby, 2013). Larger firms are better positioned to absorb costs and capitalise on efficiencies, while smaller firms may struggle. Despite initial financial strain, green innovation can drive long-term profitability through efficiencies and market positioning, particularly in environmentally conscious markets with strong policy support (Xie et al., 2019).

Given this contrasting view, this study analyses the immediate, intermediate and long-term relationships between green innovation and the financial performance of companies operating within the Chinese market. This study makes a notable contribution to the existing literature in several aspects.

We acknowledge that an existing body of literature establishes the positive relationship between green innovation and firm financial performance. However, our study extends this discourse in several meaningful ways. First, unlike previous studies that primarily examine the impact of green innovation on financial performance using static models, our study employed a long-difference multi-level fixed-effects approach to distinguish between short-term, transitional and long-term effects. Second, our findings suggest that while green innovation enhances financial performance in the transitional phase, excessive green innovation efforts may have diminished or even negative returns in the long run. This non-linear impact has not been investigated well in the existing literature. Third, we conducted a quantile analysis, demonstrating that the effects of green innovation are not uniform across firms. In particular, firms with lower ROA benefit from green innovation, whereas those with higher ROA may experience a negative impact. This heterogeneity challenges the conventional view that green innovation is universally beneficial and highlights the need for a nuanced approach when evaluating its financial implications. While numerous studies treat green innovation as a homogenous concept, our research differentiates between the quality and quantity of green innovation. High-quality innovations (substantive and strategic) positively impact ROA, whereas the sheer quantity of green innovation does not necessarily lead to financial gains. This distinction provides valuable insights for policymakers and corporate strategists in optimising green innovation investments. Finally, given China’s rapid industrialisation and ambitious environmental policies, our study provides context-specific evidence that can inform government incentives, corporate sustainability strategies and investment decisions. Unlike broad cross-country studies, we captured firm-level responses to China’s regulatory landscape and green finance initiatives.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows: Section 2 highlights theoretical underpinnings. Section 3 comprehensively reviews existing literature regarding the association between green innovation and firm performance. Section 4 explains the methodological framework and describes the data used. Section 5 describes the obtained results and presents a discussion. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study by presenting the primary findings and recommending appropriate policy implications.

Theoretical underpinningThe association between environmentally sustainable innovation and economic performance has been a subject of extensive discussion; however, the nature of this association remains complex. From the theoretical point of view, green innovation and financial performance can be understood through the resource-based view (RBV) and the stakeholder theory. RBV posits that green innovation acts as a strategic resource, providing firms with a competitive advantage through cost efficiency, differentiation and sustainability-driven capabilities (Barney, 1991; Dangelico & Pujari, 2010). Companies that develop unique eco-friendly technologies can enhance profitability by reducing operational costs and qualifying for subsidies (Zhang et al., 2020). The stakeholder theory emphasises that green innovation meets the expectations of regulators, investors and consumers, mitigating legal risks, improving reputation and attracting sustainability-focused investments (Delmas & Lim, 2016; Freeman, 1984). By integrating these perspectives, firms can leverage green innovation as a performance-enhancing strategy and a stakeholder-driven necessity, strengthening long-term financial outcomes.

The term green innovation is used to describe the development and implementation of products, processes or systems that serve to reduce environmental impacts (Deng et al., 2025; Kumar et al., 2025, Mushi, 2025; Sohag et al., 2023); it encompasses technological and non-technological advancements, such as green product development, process optimisation and organisational changes. Previous studies indicated that green innovation fulfils a dual purpose: it ensures compliance with environmental regulations while creating new market opportunities (Porter & van der Linde, 1995). Green innovation is a mediating factor in the association between green marketing and firm performance (Chen et al., 2024). These dual-purpose positions green innovation as a driver of environmental and financial benefits (Khan et al., 2024; Sohag et al., 2024b).

Review of literatureEmpirical studies investigating the association between green innovation and financial portfolio performance have yielded inconclusive results. For example, numerous studies reported that the implementation of environmentally sustainable innovations has the potential to increase the financial profitability of companies by minimising costs, enhancing resource efficiency and opening new market opportunities (Ai et al., 2024; Ambec & Lanoie, 2008; Zhang et al., 2019). Similarly, Hart and Dowell (2011) argued that green innovation provides firms with the opportunity to differentiate themselves in environmentally conscious markets, thereby fostering a competitive advantage. Furthermore, companies that adopt green technologies often experience increased market share and profitability owing to improved corporate reputation and customer loyalty (Farza et al., 2021; Ha et al., 2024). However, these financial benefits are not universal and are contingent upon numerous factors, including the specific type of innovation, market conditions and regulatory environments. For example, Horbach et al. (2012) found that process innovations often yield higher financial returns compared with product innovations primarily due to cost-efficiencies. Dos Reis Cardillo et al. (2025) and Zhu et al. (2025) reported that the impact of ESG practices on corporate financial performance is conditional to many other circumstances. In addition, stringent environmental regulations can impede the profitability of green innovators as they can restrict flexibility and increase compliance costs. Conversely, a supportive regulatory environment can facilitate the financial benefits of green innovation by reducing costs and providing incentives for investment (Ai et al., 2024).

However, environmentally sustainable innovation can also have a negative effect on the companies’ financial indicators. For example, green innovation frequently necessitates substantial initial investments in R&D, which can strain financial resources (Ai et al., 2024; Sohag et al., 2024a). Some green innovations, particularly those aimed at reducing externalities, negatively influence financial outcomes owing to the high cost (E. Vasileiou et al., 2022). Compliance with environmental regulations can impose additional financial burdens, potentially outweighing the benefits of green innovations (Aguilera-Caracuel & Ortiz-de-Mandojana, 2013). The nexus between innovation and financial gain can be U-shaped, where initial investments may inhibit performance before yielding positive returns (E. Vasileiou et al., 2022). Innovations in green processes affect financial performance in a non-linear manner; the initial negative effect becomes positive in response to high-level green innovation (Xie et al., 2022). N.M. Ha et al. (2024) suggested that the U-shaped effect is more pronounced in non-manufacturing sectors, where the cost effects are lower than those in manufacturing firms. By contrast, Wang and Yang (2025) argued that stringent policies concerning innovation can promote green innovation at the corporate level.

In the context of China, one of the main countries responsible for the greatest amount of greenhouse gas emissions, green innovation has attracted considerable attention owing to stringent environmental regulations and government incentives. Song et al. (2020) reported that Chinese companies’ green innovation and financial performance have a positive association, emphasising the role of subsidies and institutional support. Green patents can increase firm performance in China, particularly among state-owned enterprises, driven by regulatory support and green utility–model patents (Zhang et al., 2019). Zhang et al. (2020) cautioned that while green innovation may enhance long-term profitability, it often incurs high initial costs, potentially affecting short-term financial performance. These findings highlight the need for companies to adopt strategic approaches that balance environmental objectives with financial constraints.

Theoretical frameworks provide further insights into the green innovation–financial performance link. The RBV (Barney, 1991) posits that green innovation creates valuable, rare and inimitable resources, such as eco-friendly technologies and sustainable supply chains, which enhance competitiveness and financial outcomes. The stakeholder theory suggests that aligning corporate strategies with societal and regulatory expectations through green innovation enhances corporate reputation and financial performance metrics, such as ROA (Freeman, 1999). Despite these insights, gaps persist in the literature, particularly in understanding this association within emerging markets, such as China. In addition, prior studies often aggregate financial performance indicators, overlooking metrics, such as ROA, which provide a more granular view of asset efficiency. Firm-specific factors, such as size, industry type and innovation intensity, remain underexplored as potential moderators.

This study aimed to address the above-mentioned gaps by offering empirical evidence at the firm level regarding the influence of green innovation on ROA within Chinese enterprises. Different factors, including the type of innovation, financial strategies and regional policies, determine the impact of green innovation on financial performance. Substantive green innovation has been demonstrated to markedly enhance financial performance, whereas strategic green innovation may weaken it despite improving environmental outcomes (L. Liu et al., 2024). For instance, pollution prevention technologies are positively associated with future financial performance, whereas pollution control technologies are not (Cheng et al., 2024). The evidence suggests a U-shaped relationship between green innovation and financial performance, indicating that financial leverage plays a pivotal role in this relationship.

Furthermore, the implementation of deleveraging measures has been observed to enhance the positive effects observed in this association (Ai et al., 2024). High-quality green innovation is particularly effective in boosting competitiveness and financial outcomes (Liu et al., 2024), whereas green bonds facilitate capital reallocation towards R&D, mitigating financial constraints and improving performance (Dong, 2024). Moreover, combining green products and marketing innovations markedly enhances financial performance, particularly in developing economies (Appiah & Essuman, 2024).

In emerging markets, such as the MENA region, green innovation has been shown to improve ROA, particularly when coupled with innovation scores (Kasraoui et al., 2024). However, challenges such as high initial costs and risks of innovation failure can impact financial gains. External factors, including fluctuating oil prices, may further moderate these benefits, as observed in the MENA region, where high oil prices reduce the positive impact of green innovation on financial performance (Kasraoui et al., 2024).

Green innovation has been demonstrated to contribute to financial gains, although its impact is shaped by a range of internal and external factors (Sohag et al., 2023). Firms that can effectively redeploy assets are better positioned to leverage advancements in environmentally sustainable practices, particularly in high-polluting industries with regulatory uncertainties. The financial advantages of green innovation often gradually unfold, requiring a long-term strategic outlook. This study adds to the growing body of literature by exploring the complex dynamics between green innovation and financial performance, particularly in the context of emerging markets, where sustainable practices can have a substantial yet delayed effect on overall business success

MethodologyDataThis study utilised yearly data on Chinese companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. In particular, we considered A-share firms, which are also known as domestic as Chinese renminbi is used for valuation. The data include the performance of 4291 firms from 2004 to 2021. We used ROA to show the efficiency of company operation management. ROA is also a key financial metric used to evaluate a company’s profitability regarding its total assets. For Chinese companies, ROA is calculated using the same method as for companies in other countries. The formula for ROA is as follows:

In Chinese companies, net income—often called net profit in financial statements—represents the profit earned over a specific period. By contrast, total assets encompass all company-owned resources, including cash, inventory, property, equipment and intangible assets. These figures are typically found on the company’s balance sheet. Chinese A-share companies primarily adhere to Chinese Accounting Standards (CAS) when preparing their financial statements, which are reported in Chinese Yuan. Under CAS, tangible assets (e.g. property and equipment) and intangible assets (e.g. goodwill and other non-physical assets) are included in the calculation of total assets. This comprehensive approach ensures that ROA reflects the company’s efficiency in utilising all its physical and non-physical resources to generate profit.

Our main regressor is green patents, which are patents related to environmentally friendly technologies and innovations that are increasingly important for A-share companies in China, particularly as the country emphasises sustainable development and environmental protection. Green patents are valued based on their potential to generate revenue, reduce costs or enhance market competitiveness using cost, market or income approaches. Companies with green patents often benefit from government incentives, including subsidies, tax breaks and fast-track patent approvals, as part of China’s broader push towards carbon neutrality by 2060. For investors, particularly those focused on the ESG criteria, green patents signal innovation and long-term competitiveness, often enhancing a company’s market perception and stock performance. However, challenges such as valuation complexity and amortisation of finite-lived patents can impact financial reporting.

Based on their belonging to green technology innovation, green innovations are represented by patent applications for invention and utility model applications. The intellectual property portal of the World Intellectual Property Organisation provides the classification label of green patents. According to their affiliation with green technological innovations, green innovations are represented by applications for patents for inventions and utility models. Invention patents have a higher technological value and may better reflect the quality of a company’s innovations, whereas utility model patents can be considered as the quantity of green innovations (QNINO) (Zhang et al., 2023). Therefore, to represent green innovation, we utilised the data of the classification numbers of green patents for Chinese companies extracted from the China Research Data Service Platform. We used the other variables as control variables, including firm size and age, the proportion of shares held by shareholders in total ownership of banking firms and financial leverage ratio. Data on Chinese listed companies and their financial performance were obtained from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database. A more detailed description of the variables is presented in Table 1. In addition, Appendix A outlines the industry classification of our company, whereas Appendix B details its ownership structure.

Data description.

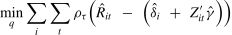

The methodological framework of this study is concentrated on the use of advanced econometric techniques for panel data analysis with high heterogeneity. Therefore, this study employed the method of moments quantile regression (MM-QR), also known as Quantile via moments approach developed by Machado and Silva (2019). This approach estimates regression quantiles by leveraging conditional means, providing an alternative to traditional quantile regression methods. This technique is beneficial in scenarios where standard quantile regression is challenging, such as with panel data models. The MM-QR approach facilitates the investigation of heterogeneous effects and distributional impacts across various quantiles. Besides, the MM-QR accounts for potential endogeneity and is useful where a specific effect influences the variation across the entire panel. This method effectively addresses locational asymmetries and yields considerable insights into non-crossing estimations within the framework of quantile regressions. MM-QR can also address the heterogeneity problem by generating heterogeneous estimates across the distribution. We determined QY(τ∣X) as the τ-th Quantile of the response variable Y given the covariate X. The conditional quantile estimations for different locations and scales are expressed as follows:

where Xit denotes the matrix of explanatory variables; parameters αi and δi capture the individual fixed effects; and Z is a k vector of differentiable transformations of the components of X. The Quantile fixed effects are determined by the scalar coefficient αi(τ)=αi+δiq(τ). The τ-th Quantile specified by q(τ) can be represented using the optimisation function derived from Eq. (2):where ρτ(A) = (τ−1)AI{A≤0}TAI{A>0} is the check function.Therefore, the model intended for estimation using Quantile via moments regression, aimed at evaluating the influence of green innovation on the operational performance of Chinese enterprises, can be expressed in the following manner:

where INO represents one of the types of green innovation analysed, including total green innovations as well as the quality and quantity of green technologies. All other variables are consistent with the data presented in Table 1.Long-difference fixed effectsA multi-level fixed-effects model is a statistical model that accounts for multiple sources of unobserved heterogeneity in the data. This model is advantageous when dealing with hierarchical data structures. The multi-level fixed-effects model deals with multiple high-dimensional fixed effects, which enable the control of unobserved heterogeneity at different levels. For example, our observations can be high discrepancies, whereas long difference multi-level fixed-effects model can tackle such heterogeneity.

The general form of a multi-level fixed-effects model can be expressed as follows (Guimarães & Portugal, 2009):

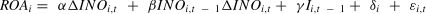

where Y denotes the dependent variable; X, the matrix of explanatory variables; β, the vector of regression coefficients for the explanatory variables; D1 and D2, the matrices of dummy variables representing the first and second high-dimensional fixed effects, respectively; α and γ, the vectors of coefficients for these high-dimensional fixed effects, respectively; ε, the error terms.In our study, the model can be represented as follows:

where δi denotes a cross-section dummy to consider companies’ fixed effects in the regression and μt denotes time-specific dummy to consider year fixed effects.Moreover, a long-difference econometric approach is employed to analyse the impact of variables over extended periods. This method enables the investigation of how one variable responds to long-run, short-run and transition changes in another variable, rather than just capture the immediate reaction. This econometric technique is particularly useful for handling clustered data structures and allows for the estimation of individual and group-level effects over time. The long-difference approach can be used in conjunction with other econometric models, including fixed-effects model in our case, to enhance the understanding of long-run economic equilibria and trends.

The long-difference model can be expressed as follows:

where α, β and γ denote the coefficients of the short-run, transition and long-run effects. Therefore, this regression can be considered as a special case of the long-difference approach proposed by Burke and Emerick (2016).ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the dependent, independent and other control variables, providing an overview of their central tendencies, variability and range. The table highlights substantial firm disparities regarding profitability (ROA), innovation metrics (GRNINO, QLTINO and QNTINO), size and leverage. These wide ranges can indicate differences in industry, market conditions or firm strategies. ROA and GRNINO have extreme maximum values, possibly due to high-performing firms or data outliers. The effect of winsorisation on ROA is evident, with reduced variability and narrower ranges, making the data more suitable for robust statistical analysis. While the mean values of GRNINO, QLTINO and QNTINO are relatively low, the high standard deviations and ranges suggest a small group of firms disproportionately driving innovation. Low mean ownership structure and leverage ratios indicate that most firms are moderately owned and financed by equity.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 presents the main findings of employing long-difference regression. Empirical analysis revealed that the impact of green innovation on the ROA of Chinese companies varies across different time horizons. The findings suggest that overall environmentally friendly innovation substantially promotes ROA in the long run and the transition period, whereas its effect remains insignificant in the short run. This suggests that the benefits of green innovation investments become more evident over time likely due to the integration process within business operations and the gradual realisation of financial gains. This finding is consistent, to some extent, with the proposition of Park and Jeong (2013). Strategic planning is crucial in the implementation of green innovations as companies must account for the time lag before their investments translate into tangible financial returns. Unlike conventional investments, green innovations often require substantial upfront costs, technological adaptation, regulatory compliance and market acceptance, all contributing to a delayed pay-off. Firms may face financial constraints, operational inefficiencies or even premature abandonment of green initiatives without a well-structured plan owing to short-term profitability concerns. Strategic planning enables firms to effectively allocate resources, manage risks and align their innovations with evolving policies and market trends. Companies can sustain their green innovation efforts by ensuring financial resilience, investing in complementary assets and adopting a long-term vision and eventually reap substantial economic and environmental benefits. As Welfens et al. (2016) suggested, allowing sufficient time for these investments to mature is essential. Still, it is through strategic planning that firms can navigate challenges and optimise the long-term gains from green innovation. This understanding highlights the importance of adopting a long-term perspective in sustainability initiatives. We acknowledge that immediate outcomes may not fully reflect the true potential of green innovation, highlighting the need for sustained commitment to achieving meaningful impact. By adopting this long-term perspective, companies can foster a culture of sustainability that not only enhances their competitive advantage but also contributes to broader environmental goals and societal well-being. By prioritising sustainable practices, companies have the capacity to enhance their brand image while captivating environmentally conscious consumers who are progressively basing their purchasing choices on the principles of corporate social responsibility. This shift towards sustainability can lead to innovative product development, operational efficiencies and, ultimately, a more resilient business model that is better equipped to navigate future challenges.

Long-difference regression.

Notes: *, ** and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance levels, respectively. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Δ or delta indicates the first difference value of the corresponding indicator and represents the result of the short-run estimates. t − 1 denotes the lag of the variable and reflects the results of long-run estimates. The multiplication of the delta with the lag reflects the results of the transition period.

When dissecting green innovation into its components, whereas the quality of green innovation emerges as a critical factor, which indicate the high-quality substantive innovations and strategic innovations aligned with government policies based on innovation motivation and subsequently evaluates the quality of green technological advancements. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that the quality of green innovation positively influences ROA in the long run but does not have a substantial impact in the short run or during the transition period. This emphasises the idea that high-quality green innovations that are more effective, efficient and potentially transformative contribute to enhanced financial performance over time. The lack of immediate impact could be attributed to initial costs, implementation challenges and the learning curve associated with the adoption of high-quality innovations.

Conversely, the quantity of green innovation does not appear to promote ROA in any of the examined periods, including long run, short run or transition period. This finding implies that simply increasing the number of green innovation activities without focusing on their effectiveness or strategic alignment does not necessarily result in improved financial outcomes. It highlights the importance of prioritising the depth and efficacy of green innovations rather than pursuing a higher volume of potentially superficial or less impactful initiatives. Furthermore, the coefficients of coefficient values for age and firm size as well as ownership structure are insignificant, whereas the leverage ratio has a positive and significant effect on ROA.

Therefore, for companies, investing in high-quality green innovations has numerous benefits, including sustainable competitive advantages, cost-efficiencies and enhanced corporate reputation, all of which positively contribute to financial gains in the long term. The insignificant short-term effects suggest that firms should adopt long-term initiatives when allocating resources to green innovation, recognising that immediate financial gains may be limited but that substantial benefits accrue over time.

The analysis presented in Table 3 includes the outliers. We conducted our analysis with them remaining in the dataset. We further estimated our model by removing the outliers through winsorisation. Hence, Table 4 presents robustness check with winsorisation of ROA, denoted here as wROA. The analysis of long-difference regression on wROA is represented in the form of three regression models specified in different columns. We observed the statistically insignificant coefficient of Δ.GRNINO in all models. This suggests no robust direct association between changes in innovation growth and ROA in the short run. By contrast, a statistically significant coefficient of GRNINOt−1 indicates a negative association between innovation growth and ROA in the long run. This finding implies that companies with higher innovation growth may experience diminishing returns on their assets in the long run. The positive and statistically significant coefficient of interaction of Δ.GRNINO and GRNINOt−1 suggests that the innovation exerts positive but small impact on WROA in the transition period. Changes in the quality of innovation insignificantly explain the short-run ROA. However, the quality of innovation is markedly enhanced in the transitional period. We observed that the quality of innovations exerted a noticeable adverse effect on ROA, whereas change in the quantity of innovation was negatively associated with ROA in the long run.

Robustness check with winsorisation of ROA.

Notes: *, ** and *** denote significance at the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance levels, respectively. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Δ or delta indicates the first difference value of the corresponding indicator and represents the result of the short-run estimates. t − 1 denotes the lag of the variable and reflects the results of long-run estimates. The multiplication of the delta with the lag reflects the results of the transition period.

The obtained empirical results also confirm that the firm size slightly but positively influences wROA, although the effect is relatively modest. Firm age negatively affects wROA, suggesting that older firms tend to have lower ROA possibly due to diminishing growth opportunities or inefficiencies associated with maturity. The statistically significant and positive coefficient on ownership structure indicates that bank-owned firms have higher ROA. The effect of the leverage ratio is negative, suggesting that high leverage negatively affects ROA. This is particularly relevant given that firms with high debt levels may face financial constraints that reduce profitability.

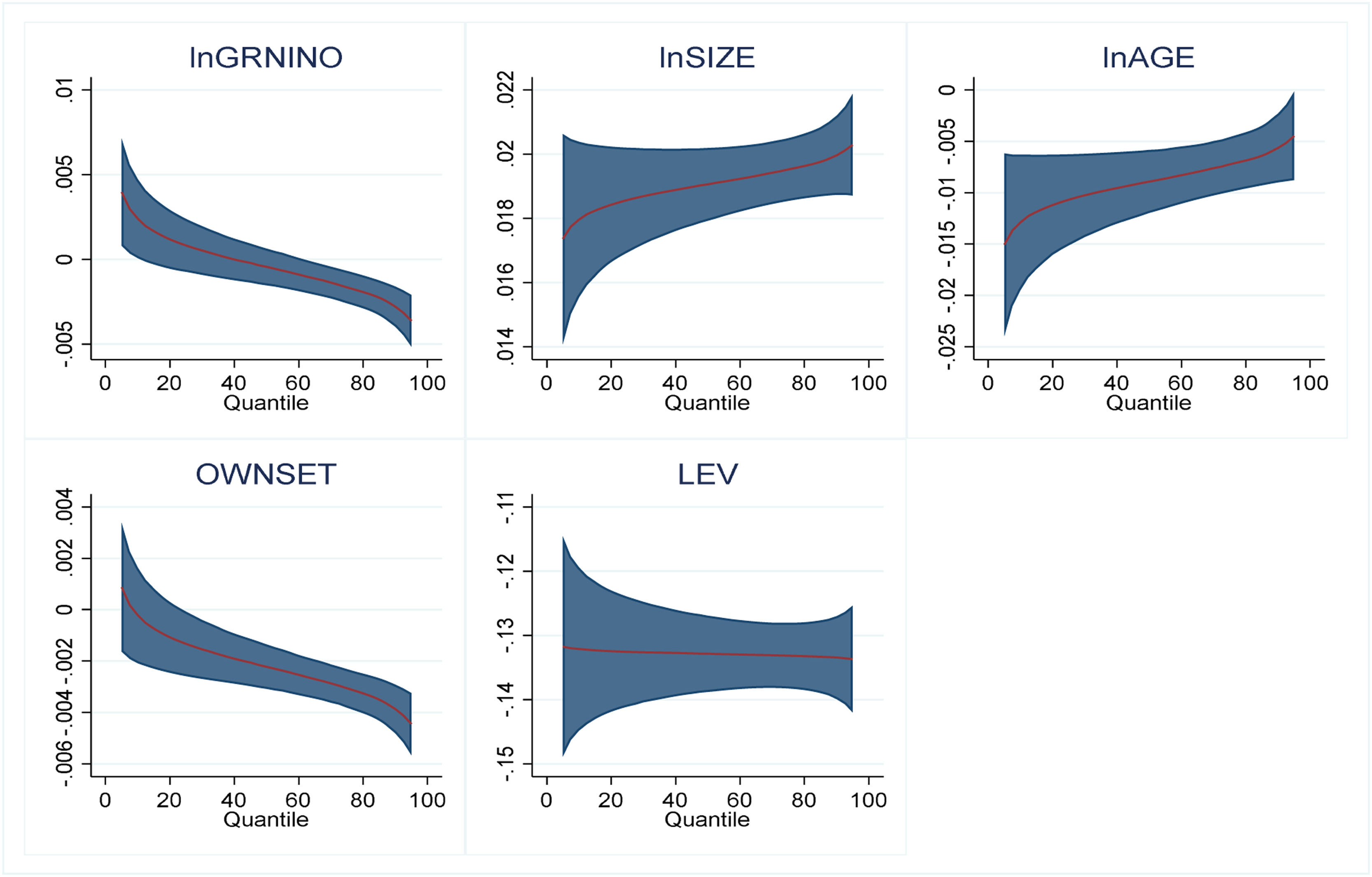

Robustness check by using quantile via momentsThis section provides the results of the Quantile via moments technique to validate the main results and estimate the impact of green innovation on firm performance at different quantiles of the dependent variable, i.e. ROA. Given that ROA serves as an indicator of corporate performance and exhibits a substantial degree of variability, it would be beneficial to examine the association between green innovation and ROA at different levels at different quantiles, where the division into quantiles corresponds to the differentiation of firms according to their performance level. Thus, the lower quantiles (Q10–Q30) refer to lower-performing firms, whereas the middle quantiles (Q40–Q60) correspond to high-performing firms. We also identified the top-performing firms included in the high quantiles (Q70–Q90). Fig. 1 presents the distribution of data according to quantiles.

The results of the Quantile via moments analysis that examined how various factors influence firm performance across different levels of the dependent variable across different quantiles (Q10–Q90) are presented in Tables 5–7. Table 5 shows the quantile regression of the impact of green innovation on firm performance using the GRNINO indicator. The location parameter represents the central tendency of the conditional distribution of the ROA, thereby representing mean values. The scale parameter reflects the dispersion or variability of the conditional distribution. It is necessary for understanding the spread of the data around the location parameter.

Quantile via moments regression for return on assets and total green innovation nexus.

Notes: a, b, c indicate the significance of the regression coefficients at 1 %, 5 % and 10 % levels, respectively. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

Quantile via moments regression for return on assets and quality of green innovation nexus.

Notes: a, b and c denote the significance of the regression coefficients at the 1 %, 5 % and 10 % levels, respectively. Standard errors are presented in the parentheses.

via moment regression for Return on assets and Quantity of Green Innovation nexus.

Notes: a, b and c indicate the significance of the regression coefficients at the 1 %, 5 % and 10 % levels, respectively. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

Results presented in Table 5 indicate the following considerable findings. First, we observed that the impact of total green innovation (GRNINO) on ROA varies from negative to positive values depending on quantiles. In the case of low-performing companies (Q1), the implementation of eco-innovation can facilitate the financial gains of Chinese companies, whereas high-performing companies (Q6) experience a slight reduction in ROA owing to the impact of green innovation. This effect becomes more pronounced at higher quantiles, where it substantially reduces performance for top-performing firms, potentially indicating diminishing returns or resource trade-offs. Firm size (SIZE) exhibits a consistently positive relationship with performance across all quantiles, with a slightly stronger effect on top-performing firms, reflecting the advantages of larger scale and resource availability. Furthermore, firm age (AGE) exerts a significant negative mean effect, indicating that older firms tend to perform worse on average, with the impact being more severe at lower quantiles and diminishing for top-performing firms. In addition, firm age contributes to increased variability in performance, as demonstrated by its positive scale effect. Besides, ownership structure (OWNST) exhibits a negative mean effect on performance, with the impact becoming more detrimental at higher quantiles, indicating that concentrated ownership structures particularly hinder top-performing firms. Moreover, the negative scale effect suggests that bank-owned firms experience lower variation in firm performance. Leverage ratio (LEV) shows a strongly negative and consistent effect on performance across all quantiles, suggesting that higher debt levels are uniformly detrimental, regardless of a firm’s performance level. The mean effect of leverage is notably large, highlighting the risks associated with high debt financing. The constant term remains positive and significant across all quantiles, reflecting a baseline level of performance independent of the predictors.

The quantile analysis revealed that the effects of innovation, firm characteristics and financial structure vary across performance levels. Fig. 2 presents the variation in the response of the ROA to these indicators at difference quantile distribution. While total green innovation and ownership structure are particularly challenging for top-performing firms, a larger firm size consistently improves performance across all levels. Older firms face diminishing performance, particularly at low quantiles, and high leverage remains a persistent negative factor. These results highlight the importance of understanding how firm-specific factors impact different segments of the performance distribution, offering essential insights for strategic decision-making and the formulation of policies.

Table 6 presents the Quantile via moments results for the regression of quality of green innovation (QLINO) on ROA. We observed that the mean (location) effect of QLINO on ROA is negative but weakly significant, indicating that higher innovation quality slightly reduces the overall firm performance on average. The scale effect is significantly negative, indicating that increased innovation quality reduces variability in firm performance. Across quantiles, the impact of QLINO is minimal at lower quantiles (Q10–Q30) but becomes significantly negative at higher quantiles, such as Q70–Q90. This indicates that a higher innovation quality may constrain performance growth for top-performing firms possibly due to resource allocation challenges or diminishing returns.

Table 7 presents the quantile response of ROA to QNINO. The results indicate that the mean (location) effect of QNINO on ROA is positive but not statistically significant. The scale effect is negative and significant, demonstrating that increased innovation quantity reduces variability in firm performance. Across quantiles, QNINO has a small but significant positive effect at lower quantiles, whereas the effect diminishes and becomes slightly negative at higher quantiles. This indicates that QNINO is more beneficial for low-performing firms but may have a marginal or negative impact on high-performing ones, potentially due to inefficiencies or oversaturation of innovation efforts. In general, QLINO has a stronger negative impact on high-performing companies, whereas QNINO is beneficial for low-performing ones; alternatively, in high-performing companies, the investment in the amount of green innovations loses its effectiveness.

DiscussionOur findings demonstrate that the short-run coefficient of green innovation (Δ.GRNINO) is insignificant across all models, indicating that short-term fluctuations in innovation growth do not immediately impact ROA. This implies that investments in green innovation do not yield instant financial gains or losses likely due to the time required for development, implementation and market adoption (Yi et al., 2021). This aligns with the broader understanding that the benefits of sustainability-driven innovations tend to materialise over the long term. As market dynamics evolve and consumer preferences increasingly shift towards sustainable practices, firms investing in green innovation may eventually experience high financial returns (Aguilera-Caracuel & Ortiz-De-Mandojana, 2013). Early adopters of green technologies may thus position themselves favourably for future growth and competitive advantage (Leyva-De La Hiz & Bolívar-Ramos, 2022). In addition, embracing sustainable practices can enhance brand reputation and help businesses mitigate the risks associated with regulatory changes and resource scarcity.

However, the statistically significant negative coefficient of lagged green innovation growth suggests a long-term adverse relationship between past innovation growth and current ROA. This implies that firms experiencing high innovation growth in previous periods may face diminishing returns over time. One plausible explanation is that continuous investment in innovation increases operational costs without generating immediate revenue, thereby impacting profitability (Shahzad et al., 2022). Moreover, this finding may reflect market saturation or the difficulty of maintaining a competitive edge solely through innovation in the long run. To address these challenges, firms must balance innovation investments with strategic resource management and market adaptability to sustain long-term profitability.

Interestingly, the positive coefficient of the interaction term between green innovation growth and its lagged value indicates a small but positive impact on ROA during the transitional period. This indicates that while initial investments in green innovation may not yield immediate benefits and could even negatively impact profitability, there is a phase where the cumulative effects of innovation start enhancing financial performance. This period may coincide with revenue generation from innovation, cost-efficiencies or increasing market recognition and reward for sustainable practices (Cappellaro, 2015).

Regarding innovation quality, our results indicate that changes in innovation quality do not significantly impact short-run ROA. However, the negative coefficient of QLTINO in the long run suggests that high-quality innovations may reduce ROA over time. This could be attributed to the substantial resources required for high-quality innovation projects, such as high R&D expenses, extended development cycles and increased implementation costs, which may initially strain financial performance. Interestingly, our findings indicate that innovation quality positively impacts financial performance during the transitional period, as reflected in the considerable interaction effects. This indicates that despite the initial financial burden, there is a critical phase where high-quality innovations begin to generate positive returns (Al-Shuaibi et al., 2016). This period likely coincides with successful commercialisation, market acceptance and the realisation of efficiency gains and competitive advantages (Poplavska et al., 2018).

In addition, we found that the growth of eco-innovation quantity is negatively associated with ROA in the long run. This suggests that simply increasing the number of green innovation initiatives may not be financially beneficial and could even adversely affect performance. Potential explanations include resource dilution, where excessive innovation projects compete for limited financial and managerial resources, thereby leading to suboptimal outcomes. Furthermore, diminishing marginal returns may play a role, as additional innovations may contribute less to financial performance owing to market saturation or inefficiencies in managing a high volume of initiatives.

Our findings highlight the complex and dynamic relationship between green innovation and financial performance. While initial and short-term impacts may be negligible or negative, innovation quality and cumulative green investments can drive financial gains during transitional periods. Firms must employ a strategic approach, balancing innovation efforts with financial sustainability and market adaptability, to maximise the long-term benefits of green innovation.

Conclusion and policy implicationsThis study determined whether green innovation promotes the respective companies’ ROA in China. We considered the short-run, transitional and long-run responses of ROA to different aspects of innovation (overall, quality and quantity) by applying a long-difference regression framework. The results indicate that green innovation, particularly in terms of its quality, positively impacts ROA in the transitional phase, highlighting the importance of high-quality innovations in enhancing firm performance. However, the QNINO appears to exert a counterproductive effect on long-term ROA, indicating that excessive focus on the number of innovations without ensuring their effectiveness can hinder financial performance.

Moreover, the quantile analysis revealed significant heterogeneity in the effects of green innovation. While firms with lower ROA benefit from green innovation, its impact turns negative for higher-performing firms, indicating that diminishing returns or resource inefficiencies may emerge at the upper end of the performance spectrum. In addition, leverage consistently plays a pivotal role in shaping ROA, highlighting the need for firms to effectively manage their financial structures to maximise the benefits of green innovation.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for policymakers and corporate strategists aiming to foster sustainable financial growth through green innovation. Policymakers should focus on creating a regulatory environment that incentivises high-quality green innovations while mitigating the financial strain on firms. Targeted subsidies, tax incentives and financial grants can encourage firms to develop impactful green technologies rather than merely increasing the quantity of eco-innovation initiatives.

Regulatory bodies should also establish clear, consistent and enforceable environmental policies that provide businesses with the certainty needed for long-term investments in green innovation. Given that excessive innovation without a strategic focus may lead to diminishing returns, policies should encourage firms to balance innovation investments with financial sustainability. In addition, financial institutions and investors can play a pivotal role by integrating green investment criteria into credit assessments, facilitating access to green finance and rewarding firms that effectively incorporate sustainability into their business models.

For corporate leaders, our results highlight the importance of aligning green innovation with firm-specific financial objectives. Instead of solely focusing on the volume of green initiatives, firms should prioritise the development of substantive, high-impact innovations that enhance efficiency, market differentiation and regulatory compliance. By integrating green innovation into core business strategies, firms can position themselves for long-term financial gains while fulfilling environmental responsibilities.

A promising avenue for future research is to investigate the mechanisms behind the impact of green innovation on firm performance. This effect may vary across industries and ownership structures. This study highlights the transitional benefits of high-quality green innovation. It also shows diminishing returns at the higher end of firm performance. A deeper examination of specific channels could provide further insights. These channels include operational efficiency, market differentiation, regulatory compliance and consumer preferences.

CRediT authorship contribution statementChanjuan Zhang: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ying Ma: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Enming Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software, Resources.