The challenges associated with achieving high Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance have become increasingly critical globally, leading to resource allocation issues, compliance complexities, and potential short-term disruptions in innovation activities, particularly within technology-intensive sectors. Despite the growing importance of ESG initiatives, limited studies in management have explored how ESG performance impacts different dimensions of firm innovation. This study investigates how ESG performance influences ambidextrous innovation, namely exploratory and exploitative innovation, among Chinese-listed new energy vehicle companies from 2009 to 2021. The findings reveal a U-shaped relationship, suggesting that initial ESG investments may hinder innovation owing to resource diversion and regulatory pressures, while sustained ESG efforts eventually lead to significant innovation gains. Government subsidies and market competition act as moderating factors in this relationship. Although both factors generally support innovation, their misalignment with ESG strategies may diminish their positive influence. Moreover, we identify financial constraints and risk propensity as mediating mechanisms. Enhanced ESG performance reduces financing barriers and encourages firms to undertake innovation-related risks. These findings offer important insights for policymakers and managers seeking to align ESG practices with innovation objectives, thereby contributing to more sustainable and balanced innovation outcomes in China and beyond.

The rapid global transition towards sustainability underscores the importance of innovation, particularly within technology-intensive sectors such as new energy vehicles (NEVs) (Helfaya & Bui, 2025). These sectors face significant challenges related to environmental concerns and resource depletion, making ambidextrous innovation—which involves the simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative innovation—essential for sustained growth and long-term adaptability (McCollum et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023; Abdelfattah & El-Shamy, 2024). Building on previous research that emphasises innovation's dual nature in technology evolution and market responsiveness (Voss & Voss, 2013; Enkel et al., 2017; Roth, Corsi & Hughes, 2024), this study argues for an expanded understanding of how corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance shapes innovation dynamics. Moreover, this study’s primary objective is to clarify how ESG performance influences exploratory and exploitative innovations in NEV firms.

Despite the rising importance of ESG globally, exemplified by robust initiatives in the EU, Norway, South Korea, France, and China to promote NEV adoption (Yakob, Nakamura & Ström, 2018; Srai et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2024), scholarly exploration into ESG’s specific role in driving ambidextrous innovation remains limited. Previous studies have highlighted ESG’s economic impacts (dos Reis Cardillo & Basso, 2025), such as reduced operational costs and improved stakeholder trust (Houston & Shan, 2022; Cao et al., 2023; Long et al., 2023; Ruan, Yang & Dong, 2024). However, little is known about whether, why, and how ESG directly facilitates innovative activities. Particularly unclear is the mediating role of internal firm factors such as financing constraints and risk-taking behaviours, and the moderating effects of government subsidies and market competition (Sun, Wang & Ai, 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

However, understanding ESG’s precise influence on corporate innovation necessitates further theoretical and empirical contributions. Integrating stakeholder and institutional theories offers a clearer understanding of how ESG engagement drives innovation. Methodologically, detailed longitudinal analyses using firm-level ESG and innovation data can provide deeper insights. Empirically, clarifying whether ESG impacts are uniform or vary according to governance structures and market conditions is essential (Nelson, Selin & Scott, 2021; Zhang, Zhu & Liu, 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). Thus, further research in these areas is crucial for comprehensively understanding ESG’s role in innovation.

To bridge these gaps, this study investigates how ESG performance critically contributes to ambidextrous innovation. Existing literature suggests that ESG can enhance firms’ resource access (Ren et al., 2022; Lei & Yu, 2024), mitigate risks, and foster long-term strategic orientations (Naimy, El Khoury & Iskandar, 2021; Iazzolino et al., 2023), which are vital for innovation activities (Azmi et al., 2021; Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2021; Waheed & Zhang, 2022). Drawing on these insights, the present study addresses the following research questions: (1) How does ESG performance impact exploratory and exploitative innovations in NEV firms? (2) How do government interventions and market competition moderate these relationships? (3) What internal mechanisms, such as financing constraints and risk-taking behaviours, mediate the ESG-innovation nexus? (4) Does firm heterogeneity influence the ESG-innovation relationship?

The study is driven by the integration of stakeholder and institutional theories to examine the ESG-innovation relationship. Stakeholder theory emphasises how firms balance diverse stakeholder interests to sustain competitive advantages (Freeman, Dmytriyev & Phillips, 2021), while institutional theory focuses on external pressures shaping organisational behaviours (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). By applying these frameworks, this study empirically investigates the impact of ESG performance on innovation activities, utilizing comprehensive panel data from Chinese-listed NEV firms between 2009 and 2021. Furthermore, the analysis incorporates patent data, Huazheng ESG ratings, and various firm-specific characteristics.

Previous literature examining ESG impacts on corporate innovation largely neglects the combined effect of governmental interventions and competitive market dynamics (Scherer, 1967; Peneder & Wörter, 2014; Luo & Tung, 2018). Thus, significant theoretical and practical questions remain unresolved (Askenazy, Cahn & Irac, 2013; Moskovics et al., 2024). Understanding how these external factors interact with ESG strategies could guide firms in effectively managing innovation activities amid regulatory and competitive uncertainties. Therefore, addressing these gaps is crucial not only for theoretical completeness but also for enhancing practical decision-making in corporate and policy environments.

This study contributes to existing scholarship in several ways. First, it enriches stakeholder and institutional theory discussions by detailing how ESG frameworks influence innovation in NEV firms, thereby enhancing theoretical and empirical insights into ESG’s operational impacts. Second, it examines how contextual factors, specifically government policies and market dynamics, moderate the ESG-innovation relationship, highlighting unique challenges within innovation-intensive sectors. Third, it uncovers internal mechanisms, particularly financing constraints and risk-taking behaviours, thereby clarifying the pathways through which ESG influences innovation. Fourth, it provides robust empirical evidence capturing multifaceted interactions among ESG performance, innovation types, governance, and market contexts. This offers a comprehensive framework beneficial for strategic management and policy formulation.

The study is organised as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical framework and hypotheses. Section 3 describes data collection and methodology. Section 4 presents empirical findings. Finally, Section 5 concludes with theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis developmentGovernment policies play a pivotal role in shaping the NEV market, significantly impacting the innovation landscape within the automotive sector. Policies adopted by various governments globally, such as production targets, financial incentives, and stringent emissions regulations, directly condition market dynamics and the strategic responses of automotive companies (Ovaere & Proost, 2022; Xu et al., 2024). For instance, countries such as Norway and the EU have implemented aggressive timelines to phase out fossil fuel vehicles, significantly driving innovation and NEV adoption (Deuten, Vilchez & Thiel, 2020; Ovaere & Proost, 2022). However, recent studies highlight potential drawbacks, indicating that certain urban mobility policies may inadvertently hinder NEV development. Specifically, restrictive urban mobility frameworks intended to curb vehicular traffic and emissions have at times discouraged consumers from investing in NEVs, raising concerns about the overall efficacy of these policy instruments in fostering sustainable automotive innovation (Oduro & Taylor, 2023; Naeem et al., 2023). Therefore, it is essential to examine the nuances of urban mobility policies and their actual impact on NEV adoption and innovation trajectories.

ESGESG factors have become integral to corporate strategies, driving significant transformations in organisational decision-making, innovation, and stakeholder interactions. Companies are leveraging ESG commitments not only as ethical imperatives but also as strategic mechanisms to enhance market credibility, reduce risk, and achieve competitive differentiation (Grewal, Riedl & Serafeim, 2019; Flammer, 2021). While ESG initiatives offer significant benefits, their implementation and measurement present considerable challenges owing to inconsistent standards and rating methodologies (Berg, Koelbel & Rigobon, 2022; Christensen, Serafeim & Sikochi, 2022). Rigorous and transparent ESG reporting supports firms in achieving more accurate and credible disclosures, promoting sustainable practices, and mitigating reputational risks associated with superficial or misleading sustainability claims. Consequently, embedding ESG into corporate strategies is essential, as it improves resource efficiency, data integrity, and stakeholder confidence—key drivers of sustainable corporate growth.

Ambidextrous innovationAmbidextrous innovation—which involves balancing exploratory and exploitative innovation—is critical for firms navigating the rapidly evolving NEV industry. Exploratory innovation involves pursuing ground-breaking technologies and market opportunities, whereas exploitative innovation focuses on incremental improvements and optimisation of existing resources (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Organisations achieving ambidexterity typically demonstrate enhanced resilience, adaptability, and competitive advantage, essential in addressing technological disruptions and market volatility (Raisch & Krakowski, 2021). In the context of NEVs, ambidexterity enables companies to leverage technological advancements, simultaneously optimizing current sustainability practices (e.g. energy efficiency, and compliance) and developing disruptive ESG-focused innovations (e.g. novel business models, and eco-innovations) (Asiaei et al., 2023; Lee, Pak & Roh, 2024). Hence, ambidextrous innovation functions as a crucial moderator, enabling effective translation of technological advancements into tangible ESG outcomes, thereby reinforcing strategic coherence, and facilitating sustainable competitive advantages.

Stakeholder theory and institutional theoryTraditional organisations adhere to a shareholder primacy principle, focusing organisational management on increasing the wealth of controlling shareholders (Mitchell, Agle & Wood, 1997). From this perspective, corporate actions and decisions often prioritise economic gains at the expense of other benefits such as societal well-being (Mitchell et al., 2016). However, stakeholder theory departs from these traditional constraints (Jones, Harrison & Felps, 2018), and asserts that firms must balance the interests of diverse stakeholder groups rather than concentrating solely on maximising shareholder returns (Kaler, 2006 & Pinto, 2019). Accordingly, organisations should broaden their objectives beyond financial metrics to incorporate social considerations (Brammer & Millington, 2008; Ioannou & Serafeim, 2012). Managers, in turn, ought to recognise and respect all individuals significantly affected by the firm’s operations and outcomes, endeavouring to address their needs.

Stakeholder theory posits that integrating diverse stakeholder groups into corporate decision-making is both an ethical obligation and a strategic asset (Barney, 2018; Freeman, Dmytriyev & Phillips, 2021). From a utilitarian stakeholder perspective, fulfilling social responsibilities fosters reciprocal ties with stakeholders, securing their support and critical resources, which in turn enables the development of competitive advantages and strengthens overall performance (Jones, Harrison & Felp, 2018; Mayer, 2021; Bacq & Aguilera, 2022; Tao, Wu & Zhao, 2023). Innovation within firms involves multiple stakeholders forming networks through contractual ties, each with distinct objective functions and priorities (Reypens, Lievens & Blazevic, 2021). During the innovation process, divergent stakeholder demands may lead to conflicts, as stakeholders dynamically adjust their subjective evaluation of the legitimacy of corporate innovation outcomes based on associated risks and rewards (Bacq & Aguilera, 2022). Corporate innovation activities are categorised into two types: exploration and exploitation (Minoja, 2012; Ahsan et al., 2023). Successful organisations manage both exploratory and exploitative innovation, thereby achieving ambidextrous innovation (Voss & Voss, 2013; Ngo et al., 2019) This enables companies to develop existing capabilities while exploring new opportunities, vital for their survival and sustained growth (Cancela, Coelho & Duarte Neves, 2023). Stakeholders’ general consensus on ESG principles builds legitimacy pressure for firms, which may choose to disclose ESG information to align with stakeholder demands. This garners recognition and support, thereby facilitating ambidextrous innovation.

Institutional theory posits that organisational structures and processes tend to seek meaning and stability rather than basing actions solely on anticipated outcomes or efficiency, such as organisational missions and objectives (Jennings & Zandbergen, 1995; Ruef & Scott, 1998). Institutional theory conceptualises institutions as the regulative, normative, and cognitive frameworks that underpin social behaviour, thereby imbuing it with both stability and meaning. The definition encompasses a comprehensive set of elements, such as laws, regulations, customs, social and professional norms, cultural values, and ethical principles, all of which collectively shape institutional environments (Kemal & Shah, 2023; Marrucci, Daddi & Iraldo, 2023). These institutional structures exert significant constraints on organisational behaviour, resulting in entities operating within the same institutional context and subject to similar external influences converging in their practices (Glynn & D’aunno, 2023; Napier, Liu & Liu, 2024). Corporate innovation results from interactions among multiple parties and is best understood within specific institutional contexts, allowing for a deeper exploration of its significance and mechanisms (Ogink et al., 2023). Typically, the enhancement of corporate innovation capabilities is driven by both government and market factors (Wang, Li & Wang, 2023). For NEV enterprises, ambidextrous innovation involves long cycles, high risks, and significant uncertainty (Peters & Buijs, 2022). Moreover, the government acts as an institutional force, playing a pivotal role in guiding ambidextrous innovation. Additionally, to expand existing market shares and enter profitable new product markets, companies may opt to continuously enhance their innovation capabilities (Tang, Zhang & Peng, 2021; Qu & Mardani, 2023). Thus, examining the ambidextrous innovation mechanisms of NEV enterprises from an institutional theory perspective holds theoretical and practical significance. In this study, both government subsidies and market competition intensity are considered part of the firms’ external institutional environment, driving them toward homogeneity to achieve market acceptance. Government subsidies and market competition intensity can positively or negatively impact how NEV firms' ESG performance drives ambidextrous innovation.

Corporate ESG performance and ambidextrous innovation in NEV firmsTraditional economic and corporate finance paradigms have long positioned firm value maximisation, with an emphasis on increasing shareholder wealth, as the primary objective guiding enterprise strategy (Queen, 2015; Battilana et al., 2022). Innovation, within this logic, serves as a vehicle to extend corporate longevity and secure supra-normal profits (Xie, Huo & Zou, 2019). However, the decoupling of ownership and control in modern corporations introduces agency problems, particularly under conditions of information asymmetry. In NEV firms, innovation projects typically involve long development cycles, high sunk costs, and substantial uncertainty (Fini et al., 2023; Yang, Zhu & Albitar, 2024). These features increase the risk of managerial risk aversion, as executives often prioritise short-term financial results tied to performance evaluations and reputational concerns. Meanwhile, external investors and financial institutions, lacking full visibility into internal operations, are often reluctant to support high-risk initiatives, preferring short-cycle and lower-risk projects (Amore, Schneider & Žaldokas, 2013).

Against this backdrop, ESG frameworks have emerged as a means of reconfiguring firm objectives and overcoming structural innovation constraints. Rooted in stakeholder theory, ESG principles shift strategic focus from a narrow financial calculus toward the broader alignment of firm activities with societal expectations and long-term value creation (Cohen & Winn, 2007; Bacq & Aguilera, 2022; Lashitew et al., 2022; Xing, Huang & Fang, 2025). ESG engagement helps firms mobilise both internal and external resources for innovation. Internally, strong ESG performance enhances employee identification and trust, facilitating the ability to attract and retain innovative talent (Lu et al., 2023). From an external perspective, enhanced legitimacy among key stakeholders, including government regulators, suppliers, and customers, contributes to improved access to subsidies, reduced resource constraints, and the development of broader collaborative networks (Lee, Pak & Roh, 2024; Luo et al., 2024; Saeedikiya, Salunke & Kowalkiewicz, 2025).

Moreover, ESG performance plays a vital governance role by mitigating principal-agent problems within NEV firms. By aligning managerial behaviour with stakeholder expectations and increasing transparency, ESG frameworks encourage managers to pursue more long-term, risk-intensive innovation strategies (Crifo, Escrig-Olmedo & Mottis, 2019). Furthermore, ESG credibility functions as a reputational buffer: when innovation projects fail, stakeholders are more likely to interpret the outcomes as part of a learning process rather than managerial incompetence (Wu, Li & Yang, 2023). This elevated trust increases organisational tolerance for failure and risk-taking (Yang, Shi & Shah, 2024). Simultaneously, ESG commitments reduce information collection costs for external stakeholders and improve oversight, enhancing firms’ capacity to engage in both exploratory and exploitative innovation (Clauss et al., 2021; Houston & Shan, 2022).

However, the relationship between ESG performance and ambidextrous innovation is not linear. At low levels of ESG engagement, firms may experience increased reporting burdens, constrained resources, and limited stakeholder recognition, all of which may hinder innovation (Liu, Zhang & Zhang, 2024). Additionally, opportunistic behaviours among senior managers may arise, such as diverting resources away from R&D when ESG governance is weak (Jiao, Shuai & Li, 2024; Otto et al., 2024). In contrast, once ESG performance surpasses a critical threshold and becomes institutionally recognised, it yields net positive effects. A strong ESG performance fosters a heightened sense of responsibility among senior executives (Baek & Lee, 2024), enhances employee engagement, and secures broader stakeholder support, thereby collectively fostering an environment conducive to ambidextrous innovation (Tajeddini et al., 2024).

Overall, strong ESG performance supports the advancement of both exploratory innovations—oriented toward novel technologies, business models, or sustainable energy solutions—and exploitative innovation, aimed at enhancing operational efficiency and refining existing products. As such, ESG practices serve as a strategic mechanism through which NEV firms can overcome traditional innovation barriers, mitigate agency conflicts, and align their long-term environmental and economic objectives. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a The relationship between the ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploratory innovation is ‘U-shaped’: ESG performance above a certain threshold can promote a company's exploratory innovation.

H1b The relationship between the ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploitative innovation is ‘U-shaped’: ESG performance above a certain threshold can promote a company's exploitative innovation.

According to institutional theory, firms that align their strategies and practices with external institutional expectations, including government policies, are more prone to survive and experience long-term growth (Dacin, Oliver & Roy, 2007; Greenwood et al., 2011). Within this framework, government subsidies function as key instruments to correct market failures in R&D by mitigating innovation risks and encouraging technological advancement (Klette, Møen & Griliches, 2000; Song et al., 2022). These supports, which range from fiscal grants to tax incentives, reduce innovation costs and facilitate performance improvements (Leung & Sharma, 2021; Yi et al., 2021).

For NEV firms facing high uncertainty and weak short-term incentives, subsidies can promote ambidextrous innovation by easing financial constraints and signalling legitimacy (Peters & Buijs, 2022; Christofi et al., 2024; Schiefer et al., 2024). Firms meeting environmental performance thresholds (e.g. low emissions) are more likely to receive support, thereby accelerating both exploratory and exploitative innovation (Abbas et al., 2024; Badu & Micheli, 2024; Kwilinski, Lyulyov & Pimonenko, 2025).

Yet, subsidies also risk inducing adverse effects. Weak oversight may prompt firms to pursue ‘window-dressing’ projects that feign innovation to access funds, only to abandon them after disbursement (Jain et al., 2024). Since the 2009 NEV subsidy rollout, policy shifts have broadened coverage, but inconsistent local implementation has sometimes undermined national objectives, supporting inefficient firms and distorting market selection mechanisms (Meng, Li & Cao, 2024; Sun et al., 2024; Tao, 2024). Moreover, this has encouraged rent-seeking behaviours and resource misallocation, thereby weakening firms’ intrinsic motivation to innovate (Zhao et al., 2024).

Accordingly, while subsidies can alleviate resource constraints, they may also dilute the positive innovation effects of ESG performance, especially when misused. As such, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2a Government subsidies negatively moderate the relationship between the ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploratory innovation, that is, they weaken the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between the two.

H2b Government subsidies negatively moderate the relationship between the ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploitative innovation, that is, they weaken the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between the two.

Market competition intensity reflects the degree of rivalry a firm faces, often shaped by the number, capability, and strategic aggressiveness of its competitors (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Leppänen, George & Alexy, 2023). In resource-constrained markets, heightened competition compels firms to invest in scanning and interpreting external signals to mitigate uncertainty and maintain competitiveness (Morandi, Santalo & Giarratana, 2020; Lee, Narula & Hillemann, 2021). Theoretical and empirical studies reveal a non-linear relationship between competition and innovation. While moderate competition may stimulate innovation by pressuring firms to differentiate, excessive competition can deter R&D investment owing to diminished appropriation and uncertain returns (Utterback & Suárez, 1993; Ang, 2008; Peneder & Wörter, 2014; Bento, 2020). Intense competition, coupled with rapid imitation and insufficient appropriation of innovation rents lead firms to scale back innovation initiatives (Park, Srivastava & Gnyawali, 2014).

Moreover, highly competitive markets create disincentives for R&D manipulation, as firms with strong reputational capital and high market share are less willing to undertake risky behaviour that could draw regulatory scrutiny (Jermias, 2008; Suder et al., 2025). In such environments, firms prioritise stability over experimentation, opting for safer, short-term innovation activities aligned with operational efficiency and incremental market expansion.

In the context of NEV firms, this study posits that intense market competition negatively moderates the U-shaped relationship between ESG performance and ambidextrous innovation. Under conditions of intense competition, firms—even those with sufficient resources—may avoid ambidextrous innovation strategies owing to their long-term investment horizons, high costs, and elevated uncertainty levels. Instead, they focus on less risky, efficiency-driven initiatives that offer immediate competitive advantages. Accordingly, this study proposes:

H3a Market competition intensity negatively moderates the relationship between ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploratory innovation, that is, it weakens the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between the two.

H3b Market competition intensity negatively moderates the relationship between ESG performance of NEV companies and their exploitative innovation, that is, it weakens the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between the two.

Financing constraints are a critical barrier to corporate innovation, particularly in high-risk, long-horizon R&D activities that demand stable and patient capital (Zhang et al., 2024). Owing to information asymmetries, financial institutions often exhibit reluctance in funding such projects, especially in contexts such as China where capital markets are less mature and equity financing options are limited, particularly for innovation-intensive small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Cumming, 2007; Li et al., 2023). Alleviating financing constraints is therefore essential for promoting both exploratory and exploitative innovation.

Strong ESG performance offers a potential pathway to reduce these constraints. Prior studies highlight that ESG engagement enhances corporate transparency, thereby reducing information asymmetry and increasing investor confidence (Raimo et al., 2021; Reber, Gold & Gold, 2022). From a signalling theory perspective, firms that consistently disclose credible ESG and financial information improve their legitimacy in the eyes of external stakeholders (Kirmani & Rao, 2000; Colombo, 2021). While ESG initiatives may entail substantial costs, they convey positive signals regarding a firm's operational robustness and ethical governance, especially when accompanied by high-quality financial disclosure (Bofinger, Heyden & Rock, 2022; Song et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2024). Moreover, ESG reporting is associated with reduced earnings manipulation and stronger governance practices, further reinforcing trust (Rezaee & Tuo, 2019).

Consequently, firms with strong ESG performance are more likely to access favourable financing conditions from investors, creditors, and suppliers (Chen, Song & Gao, 2023). In contrast, weak ESG performers may face reputational risks, regulatory pressure, and financial exclusion, thereby worsening their capital constraints (Kölbel, Busch & Jancso, 2017; Chen, Dong & Lin, 2020). Given the centrality of financing to innovation outcomes, ESG thus indirectly influences firms’ capacity to undertake ambidextrous innovation by mitigating funding limitations.

Accordingly, this study proposes:

H4a The financing constraints of NEV companies play a mediating role in the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between their ESG performance and exploratory innovation.

H4b The financing constraints of NEV companies play a mediating role in the ‘U-shaped’ relationship between their ESG performance and exploitative innovation.

Organisational risk propensity plays a pivotal role in shaping firms’ innovation strategies. In many firms, equity-based incentives and performance evaluation systems emphasise short-term financial outcomes, incentivizing managers to prioritise low-risk, high-certainty projects over long-term, uncertain innovation investments (Dalton et al., 2007; Zhang & Gimeno, 2016; Faller & zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, 2018). Entrepreneurial firms, although generally more risk-tolerant during their initial development phases, often adopt more conservative strategies as they attain market stability and financial security (Lieberman, Lee & Folta, 2017). In environments lacking rigorous external oversight, this bias toward predictability is further reinforced by stakeholders who prefer stable returns, thereby collectively diminishing the organisation’s overall risk appetite (Wang & Bansal, 2012; Ortiz-de-Mandojana & Bansal, 2016).

Adopting strong ESG practices offers a pathway to counteract excessive risk aversion. ESG frameworks help address principal-agent problems by aligning managerial incentives with long-term, sustainability-oriented objectives (Aguilera et al., 2021; Derchi, Zoni & Dossi, 2021). Integrating ESG goals into executive compensation and reporting broadens corporate accountability beyond shareholder value to include wider stakeholder concerns, encouraging a strategic orientation that supports long-term innovation (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Flammer, 2018). Notably, firms with strong ESG reputations are more likely to benefit from stakeholder goodwill and trust, fostering a more tolerant external environment in which innovation failures are attributed to uncontrollable factors rather than managerial misjudgement (Dickson, Weaver & Hoy, 2006; Sun et al., 2024). This higher tolerance for failure ultimately enhances firms’ willingness to engage in both exploratory and exploitative innovation.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5a The risk propensity of NEV companies mediates the U-shaped relationship between their ESG performance and exploratory innovation.

H5b The risk propensity of NEV companies mediates the U-shaped relationship between their ESG performance and exploitative innovation.

Overall, the conceptual model presented in Fig. 1 delineates the impact of ESG performance on ambidextrous innovation within NEV companies.

MethodsData and sampleThis study examines the relationship between ESG performance and ambidextrous innovation, which encompasses both exploratory and exploitative innovation, using data from Chinese listed NEV firms between 2009 and 2021. ESG performance scores were obtained from the Wind financial terminal, a widely used data source in Chinese capital market research. Innovation indicators were constructed using firms’ stock codes to match patent data from the China State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO). Building on established research, this study aligns patent types with innovation modes to operationalise the exploration versus exploitation dichotomy. Invention patents undergo rigorous substantive examination and must satisfy strict criteria for novelty, inventive step, and utility. These requirements reflect a firms’ pursuit of fundamentally new technological principles or breakthrough solutions, making invention patents widely accepted as indicators of exploratory innovation (Wang et al., 2014; Guan & Liu, 2016; Rong, Wu & Boeing, 2017). In contrast, utility-model and design patents are subject to a shorter, less demanding review that focuses on incremental modifications to product structure, form, or function, making them suitable proxies for exploitative innovation (Beneito, 2006; Guan & Liu, 2016; Hu, Pan & Huang, 2020). The distinction is particularly salient in China, where invention patents typically require more than two to three years for authorisation and are often filed before commercialisation, signalling high uncertainty and forward‑looking R&D, whereas utility-model and design patents are usually granted within six to twelve months, matching firms’ needs for rapid product iteration and market responsiveness. These temporal and procedural contrasts mirror Katila and Ahuja’s (2002) dual logic in which exploratory innovation focuses on discovering new knowledge, whereas exploitative innovation deepens and recombines existing knowledge. Accordingly, this study measures exploratory innovation by the count of invention patents and exploitative innovation by the combined count of utility-model and design patents. Additional firm-level financial and governance variables were sourced from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database.

To ensure the robustness and reliability of the dataset, several data-cleaning procedures were implemented. First, we excluded firms in the financial sector owing to their unique regulatory environments and balance sheet structures, which differ significantly from those of industrial firms. Second, firms classified as Special Treatment (ST or *ST) in a given year, often as a result of financial distress or regulatory infractions, were excluded from the sample to minimise potential bias arising from atypical firm behaviour. Third, firms with substantial missing data on key variables were excluded from the sample. Finally, all continuous variables were winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of extreme outliers. These steps align with established empirical practices and enhance the validity of the regression results.

The selection of listed NEV companies as the study sample is supported by three key considerations. First, in light of the ‘dual carbon’ objectives and the broader green economy initiative, advancing energy-efficient and low-carbon transportation is essential for sustainable national development. Second, while NEVs are widely recognised as the future of the automotive industry, China continues to face substantial technological hurdles, especially in core areas such as power batteries, motor systems, and other essential components. These challenges underscore the pressing need to strengthen innovation capabilities. Third, publicly listed companies offer a more robust and accessible source of data, as financial disclosures and annual reports provide reliable information for measuring the variables of interest.

Main variablesDependent variablesIn line with prior research that employs patent counts as a proxy for innovation performance (Fleming & Sorenson, 2004), this study adopts established ambidextrous innovation measurement approaches (Cui, Ding, & Yanadori, 2019). Specifically, exploratory innovation is measured as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of invention patents independently filed by listed NEV firms, while exploitative innovation is captured by the logarithm of one plus the number of utility model and design patents independently applied for. To construct these measures, we extracted patent application and grant data from the SIPO using the firms’ stock codes. Next, we manually filtered the data using International Patent Classification (IPC) codes to distinguish between invention patents and non-invention patents (i.e. utility models and design patents), and aggregated the counts on an annual basis.

Independent variablesThe explanatory variable, ESG, is operationalised using the Huatai Securities ESG rating system, which categorises companies into nine levels: C, CC, CCC, B, BB, BBB, A, AA, and AAA. In this framework, listed companies are assigned a numerical score from 1 to 9 in ascending order of ESG performance. The corporate ESG metric is then defined as the natural logarithm of one plus the annual average of these ratings. Given the extensive temporal coverage and broad applicability of the Huatai Securities ESG ratings, this measure is employed as a proxy for corporate ESG performance. Notably, Huatai Securities has been assessing ESG performance for A-share and bond issuers since 2009, and its rating system now covers all A-share listed companies, garnering widespread recognition in both academic and industry circles.

Moderating variablesThis study incorporates government subsidies and market competition intensity as key variables. For government subsidies, the focus is on R&D support mechanisms, encompassing fiscal subsidies, innovation awards, and support funds identified through keywords such as R&D, technology, innovation, science and technology, and intellectual property (Guo, Guo, & Jiang, 2016). These subsidies are quantified in billions. To gauge market competition intensity, the analysis employs the inverse of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a well-established metric for assessing industry concentration (Wang & Zhang, 2015). The HHI is calculated as the sum of the squares of the revenue shares of all firms within an industry, where higher values indicate greater market concentration and reduced competitive pressure. By taking the inverse of the HHI, the resulting measure effectively reflects the intensity of market competition.

Mediating variablesFollowing Hadlock and Pierce (2010), this study employs the SA Index as a proxy for financing constraints, which effectively quantifies the external funding challenges faced by firms. In parallel, to gauge a firm's risk propensity, we adopt the approach used by Galletta and Mazzù (2023), and Cui, Ding, and Yanadori (2019), measuring it as the ratio of R&D personnel to the total workforce. This ratio serves as an indicator of the firm’s willingness to engage in risky and innovative activities.

Control variablesDrawing on prior studies (Cronqvist & Yu, 2017; Di Giuli & Kostovetsky, 2014; Ferrell, Liang, & Renneboog, 2016), this analysis incorporates several firm-level control variables to mitigate confounding influences. Specifically, we include the cash ratio, profitability, firm age, selling expense ratio, quick ratio, and financial expense ratio. The corresponding data for these variables are primarily sourced from the CSMAR database.

Estimation methodsBased on the theoretical framework proposed by Hausman and Taylor (1981), this study adopts a negative binomial regression model to test the proposed hypotheses. Variance inflation factors were calculated for all regression models, with all values well below the conventional threshold of 10 (Gujarati & Porter, 2009; Kutner, Nachtsheim & Neter, 2004), indicating minimal multicollinearity. The selection of the model is informed by the characteristics of the dependent variables, as the number of patents filed by firms constitutes non-negative integer count data, warranting the use of appropriate count-based regression techniques. Moreover, both exploratory and exploitative innovation measures exhibit clear signs of overdispersion, as the variance (i.e. the square of the standard deviation) substantially exceeds the mean, thereby satisfying the distributional assumptions of the negative binomial model.

To mitigate potential heterogeneity across firms and enhance the robustness of the regression results, we conducted a Hausman test using Stata software to determine the appropriate model specification. The test results support the use of a fixed effects model. Accordingly, we implemented a fixed effects negative binomial regression analysis on the panel dataset. Table 1 reports the Hausman specification tests that guide the selection between fixed effects and random effects estimators. In every model specification, including the baseline regressions for exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation and the interaction models that combine ESG performance with government subsidies or market competition, the chi-square statistics are large and all p-values are below 0.001 (for example, χ² = 70.19 for the exploratory innovation baseline model and χ² = 172.15 for the exploratory innovation model with government subsidies). These results reject the null hypothesis—that fixed effects and random effects coefficients are equal—which implies that the explanatory variables correlate with unobserved, time‑invariant firm characteristics. Under such circumstances, random effects estimates become inconsistent, whereas fixed effects estimates remain consistent. Consequently, we select the fixed effects estimator for all subsequent analyses. Adopting a fixed‑effects negative binomial regression allows us to control for firm‑specific heterogeneity that remains constant over time, enabling robust within‑firm estimates of the influence of ESG performance—along with its interactions with government subsidies and market competition—on both exploratory and exploitative innovation.

Summary of Hausman test results for model selection.

To examine the impact of ESG performance on exploratory and exploitative innovation in new energy vehicle companies, this paper constructs the following models (where the subscripts iand trepresent the sample individual and year, respectively):

To empirically assess the influence of ESG performance on both exploratory and exploitative innovation in new energy vehicle firms, we specify the following econometric models. In these models, the subscriptidenotes individual firms andtdenotes the year:

Main effect model:

Model under the moderating effect of government subsidies:

Model under the moderating effect of market competition intensity:

Model for testing the mediating effect of financing constraints:

Model for testing the mediating effect of risk propensity:

In these models, the dependent variableEIrepresents exploratory innovation of the firm, and LIrepresents exploitative innovation of the firm. The key explanatory variableESGis the annual average of the Huatai SecuritiesESGrating. The moderating variablesGS,MCrepresent government subsidies and market competition intensity, respectively. The mediating variables FC,RPrepresent financing constraints and risk propensity. In addition, all models include fixed year effects to control for annual variations, and the error termεi,tis captured in the residuals.

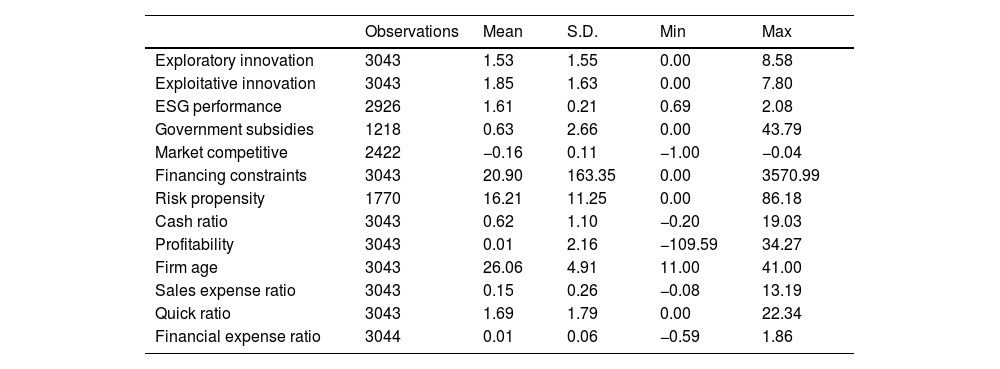

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 2 summarises the descriptive statistics of the primary variables used in this study. Exploratory innovation values range from 0 to 8.58, with a standard deviation of 1.55, suggesting considerable variability. Similarly, exploitative innovation spans from 0 to 7.80 with a standard deviation of 1.63. For ESG performance, the measured values lie between 0.69 and 2.08, with a standard deviation of 0.21. These figures indicate that both types of innovation display significant dispersion and volatility. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix for the main variables, providing further insight into their interrelationships.

Descriptive statistics.

Correlation matrix.

The outcomes of these regressions are presented in Table 4. Specifically, columns (1) and (2) include both the ESG performance variable and its squared term, along with a set of control variables, to evaluate their effects on exploratory and exploitative innovation, respectively. Columns (3) and (4) then examine how government subsidies moderate the relationship between ESG performance and both types of innovation. Finally, columns (5) and (6) explore the moderating effect of market competition intensity on the ESG–innovation relationship for exploratory and exploitative innovation.

Results of fixed effects negative binomial regression.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Fixed effects negative binomial estimates in Table 4 indicate a statistically significant U-shaped association between ESG performance and corporate innovation. For exploratory innovation, ESG performance exerts a significant negative linear effect (β= −2.433, p < 0.01) and a significant positive quadratic effect (β = 1.138, p < 0.01). For exploitative innovation, the pattern is similar: the linear term is significantly negative (β = −1.770, p < 0.05) and the squared term significantly positive (β = 0.795, p < 0.01). These coefficient signs and significance levels confirm Hypotheses H1a and H1b, indicating that ESG improvements initially dampen innovation but, beyond a certain threshold, have a positive, innovation‑enhancing effect.

Introducing government subsidies alters this curvature. When the interaction between ESG² and subsidies is included, its coefficient is negative and marginally significant for both exploratory (β = −0.028, p < 0.10) and exploitative (β = −0.024, p < 0.10) innovation. These results suggest that subsidies flatten the U‑shape, implying that the innovation‑boosting threshold is reached earlier, but the subsequent acceleration is more moderate. Accordingly, Hypotheses H2a and H2b are supported.

Market competition exerts an even stronger moderating influence. The interaction between ESG² and competition intensity is significantly negative for exploratory innovation (β = −8.123, p < 0.05) and exploitative innovation (β = −5.752, p < 0.10). Greater competitive pressure therefore further flattens the ESG curve, weakening the incremental innovation gains at higher ESG levels and validating Hypotheses H3a and H3b.

Testing the mediating mechanisms(1) Financing constraints are recognised as a major impediment to corporate innovation. The core objective of ESG initiatives is to reorient corporate priorities from a singular focus on maximising economic profits toward achieving a balance between economic and social values. This strategic shift can bolster a firm's credibility with financial institutions and other stakeholders, thereby facilitating access to the necessary funds for innovation. Drawing on Hadlock and Pierce (2010), we use the SA index to proxy financing constraints. The SA index is calculated as:

Column (1) of Table 5 illustrates that the linear ESG term is statistically indistinguishable from zero (β = –0.554, n.s.), whereas the quadratic term is positive and marginally significant (β = 0.231, p < 0.10). This pattern indicates a U‑shaped association between ESG performance and financing constraints: modest ESG efforts tighten financing, but stronger ESG commitments eventually ease firms’ funding frictions. Turning to innovation outcomes, columns (2) and (4) reveal that reduced financing constraints have a pronounced positive impact on both exploratory innovation (β = 0.656, p < 0.01) and exploitative innovation (β = 0.468, p < 0.01). When financing constraints are introduced into the innovation equations (columns 3 and 5), their coefficients remain strongly positive (exploratory: β = 0.572, p < 0.01; exploitative: β = 0.409, p < 0.01) while the magnitude of the ESG‑squared term decreases, consistent with partial mediation. Thus, alleviating financing constraints constitutes a key channel through which ESG performance stimulates both exploratory and exploitative innovation, thereby supporting Hypotheses H4a and H4b. Robustness checks employing Poisson and alternative specifications (columns 6–10) deliver parallel signs and significance levels, confirming that the mediating role of financing constraints is stable across estimation methods.

(2) Risk propensity mechanism. Corporate management typically avoids high-risk innovations owing to political repercussions and career risks linked to project failures. ESG initiatives mitigate these concerns by reducing principal-agent conflicts among owners, managers, and stakeholders, thus fostering higher risk propensity and a more innovation-friendly environment.

Testing the mediating role of financing constraints and robustness of results.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Column (1) of Table 6 illustrates that ESG performance initially lowers a firm’s risk‑taking propensity; however, once a certain threshold is exceeded, it begins to increase. Specifically, the linear ESG term is negative and marginally significant (β = −0.929, p < 0.10), whereas the quadratic term is positive and marginally significant (β = 0.378, p < 0.10), confirming a U‑shaped association. Risk propensity, in turn, exerts a strong positive influence on innovation. As exhibited in columns (2) and (4), a one‑unit increase in risk propensity raises exploratory innovation by β = 0.017 (p < 0.01) and exploitative innovation by β = 0.009 (p < 0.01). When risk propensity is included in the innovation equations (columns 3 and 5), its coefficient remains positive and highly significant (exploratory: β = 0.015, p < 0.01; exploitative: β = 0.008, p < 0.01), while the magnitude of the ESG‑squared term drops from 0.840 to 0.755 in the exploratory model and from 0.864 to 0.752 in the exploitative model. This attenuation is consistent with partial mediation, indicating that a firm’s heightened willingness to take risks represents one pathway through which ESG engagement stimulates both types of innovation, thereby supporting Hypotheses H5a and H5b. Finally, alternative specifications reported in columns (6)–(10) yield parallel signs and significance levels, confirming that the mediating role of risk propensity remains robust across different estimation techniques.

Testing the mediating role of risk propensity and robustness of results.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 7 consolidates the key coefficients that correspond to each theoretical prediction. For the U-shaped effects (H1), we report the linear and quadratic ESG terms. For the moderation hypotheses (H2–H3), we provide the interaction terms with the linear and quadratic ESG components. For the two mediation hypotheses (H4–H5), we report (i) the effect of ESG² on the mediator (path a), and (ii) the effect of the mediator on innovation (path b). Significance levels are reported in accordance with the original tables (*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.10). All coefficients are derived from the fixed effects negative binomial models reported in Tables 4–6.

Hypothesis test results.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

To ensure the validity of the primary results, we implemented a series of robustness checks. First, we applied alternative regression techniques to verify that the estimated relationships were not an artifact of a particular methodological approach. Second, we addressed potential endogeneity concerns through appropriate econometric strategies. The consistency of the results across these various tests reinforces the robustness of the conclusions.

- (1)

Changing the regression method. To verify the robustness of the findings, we re-estimated the models using a Poisson regression framework, as presented in Table 8. The results obtained through this alternative approach are largely consistent with the previous estimates. All hypothesised relationships remain statistically significant, thereby reinforcing the validity of the original findings and confirming that all hypotheses hold under this specification.

Table 8.Poisson regression results.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

- (2)

Addressing issues of endogeneity. Given that a firm's capacity for technological innovation may also influence its ESG rating, there exists a potential issue of reverse causality and endogeneity between ESG and dual innovation within companies. Moreover, to address concerns that omitted variables might affect dual innovation, we implement an Instrumental Variable (IV) approach. This strategy helps mitigate endogeneity issues by isolating the causal impact of ESG performance on both exploratory and exploitative innovation, thereby reinforcing the robustness.

This study employs the number of ESG fund holdings as IV to proxy for corporate ESG performance. This choice is justified on several grounds. First, ESG funds, as prominent institutional investors, influence corporate governance and management practices through mechanisms such as ‘voting with their feet’ and continuous oversight. By incorporating their investment philosophy into company operations, ESG funds improve companies’ ESG performance, thus fulfilling the relevance criterion. Second, it is unlikely that ESG funds directly affect the innovation investments of companies. This is because ESG funds typically do not interfere directly in the day-to-day operations of companies but may engage in private dialogues with executives to enhance ESG performance. The realisation of their investment philosophy primarily depends on the fund managers' stock selection and other decision-making processes. Furthermore, corporate innovation relies significantly on participants' knowledge and technical skills in specific scientific or engineering fields, which surpasses the general qualifications expected of fund investment personnel, thereby meeting the exclusivity criterion.

Table 9 reports the results from the IV analysis. In column (1), the first-stage regression uses the number of ESG fund holdings as an instrument to explain corporate ESG performance. The predicted ESG values derived from this stage are then incorporated into the second-stage regressions, with the results for exploratory and exploitative innovation presented in columns (2) and (3), respectively. Notably, the squared ESG term remains significantly positive at the 1 % level in both models, thereby reinforcing the previous findings and confirming the robustness of the U-shaped relationship between ESG performance and dual innovation.

Instrumental variable (IV) regression results.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Furthermore, the statistical results from the identification test and weak instrument variable test indicate that there are no issues of under-identification or weak instruments in this study. Additionally, since the number of IVs (ESG fund holdings) does not exceed the number of explanatory variables (corporate ESG), over-identification is not a concern. Ultimately, the regression results demonstrate that after controlling for potential endogeneity issues, the conclusions of this study remain robust.

Heterogeneity testThe ownership structure of firms may significantly influence the relationship between ESG performance and ambidextrous innovation in the NEV sector. State-owned enterprises (SOEs), which operate under stringent governmental oversight and carry substantial social responsibilities, embody both economic and political attributes. With the growing emphasis on sustainable development, SOEs have increasingly become pivotal instruments for government-led high-quality growth. As a result, compared to private firms, SOEs tend to experience more rigorous environmental regulatory pressures and enhanced market supervision. This study further examines how these ownership attributes affect the interplay between ESG performance and both exploratory and exploitative innovation in NEV companies.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 10 reveal that state ownership negatively moderates the U-shaped relationship between ESG performance and exploratory innovation in NEV companies. In contrast, state ownership does not significantly affect the U-shaped relationship between ESG and exploitative innovation. One possible explanation is that SOEs typically feature elongated principal-agent chains and less rigorous supervisory and constraint mechanisms compared to private firms. This structural rigidity can dampen entrepreneurial spirit, resulting in inflexible management practices and weaker incentive systems. Leadership appointments and promotions in SOEs are often determined by higher-level authorities, which tend to emphasise short-term performance outcomes over long-term, higher-risk innovation. Consequently, SOE leaders are less inclined to invest in exploratory innovation, which generally involves longer cycles and greater uncertainty.

Analysis of heterogeneity in corporate ownership attributes.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Moreover, SOEs usually face fewer financing constraints, therefore, the influence of ESG performance on their financial conditions is relatively muted. As exploratory innovation demands substantial technological input, higher costs, and acceptance of greater uncertainty, SOEs are less proactive in these areas compared to private enterprises. Therefore, the ESG–exploratory innovation relationship is attenuated in SOEs.

Conversely, exploitative innovation, characterised by incremental improvements aimed at enhancing innovation output and operational efficiency, is common to both SOEs and private companies. As exploitative innovation is less specialised, less confidential, and less affected by information asymmetries in capital markets, it encounters smaller principal–agent problems. As a result, the impact of ESG performance on exploitative innovation does not differ significantly between SOEs and non-SOEs.

Robustness tests, which involved changing the regression method and re-estimating the models (as depicted in Table 11), yield results that are essentially consistent with the earlier findings, thereby confirming the robustness of the heterogeneity outcomes related to ownership attributes.

Robustness test for corporate ownership attributes.

Note: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Drawing on an integrated stakeholder and institutional perspective, we investigate how ESG engagement influences exploratory and exploitative innovation among Chinese NEV firms from 2009 to 2021. In contrast to the prevailing view that superior ESG performance consistently boosts innovation (Eccles, Ioannou & Serafeim, 2014; Broadstock et al., 2020), the findings reveals a contingent U-shaped association. When ESG capabilities remain below a threshold, compliance tasks absorb managerial attention and reallocate slack resources, thereby suppressing both exploration and exploitation. Once firms surpass this capability threshold, accumulated routines, enhanced legitimacy, and stronger stakeholder goodwill collectively spur dual-mode innovation. This finding aligns with capability life-cycle theory, which describes early adjustment costs followed by delayed returns in emerging organisational practices (Teece, 2007).

The upward segment of this curve is carried by two parallel mechanisms. First, credible ESG disclosure eases financing constraints, lowering the cost of external capital and enlarging the pool of funds available for R&D (Ioannou & Serafeim, 2015). Second, heightened ESG credibility increases managerial tolerance for uncertainty, leading to a greater willingness to invest in risky projects that underpin both exploratory breakthroughs and incremental improvements (Cucculelli & Bettinelli, 2015). Demonstrating these financial and behavioural channels within a single analytical framework extends existing micro-foundation research, which often examines them separately (Hafenbrädl & Waeger, 2017). Additionally, it underscores the need to view ESG as deeply embedded in resource allocation and decision-making processes rather than as a purely symbolic initiative.

External context significantly moderates the ESG-innovation relationship. Government subsidies and intense product-market competition flatten the rebound of the U-shape, indicating partial substitution between externally provided incentives and ESG-derived advantages. While prior work emphasises the innovation-stimulating effects of regulation and rivalry (Porter & Linde, 1995; Delmas & Toffel, 2008), the results suggest that excessive external pressure can hinder the learning benefits that arise from internally driven ESG initiatives. Ownership structure offers further nuance: SOEs, constrained by administrative routines, translate ESG credibility into dynamic innovation less effectively than private firms. Taken together, the findings clarify when ESG initiatives hinder or enhance innovation, the internal channels through which they operate, and the institutional conditions under which their impact is most pronounced.

Theoretical implicationsThis study makes four key theoretical contributions to the literature on ESG, innovation management, and sustainability strategy domains.

First, we enrich existing research on the relationship between ESG performance and innovation by revealing a nonlinear, U-shaped association with both exploratory and exploitative innovation. While prior studies often assume a positive and linear relationship, suggesting that higher ESG performance invariably leads to improved innovation outcomes (Eccles, Ioannou & Serafeim, 2014; Broadstock et al., 2020; Clementino & Perkins, 2021), the study’s findings challenge this orthodoxy. By identifying a performance threshold beyond which ESG engagement catalyses innovation, we demonstrate that ESG initiatives initially impose adjustment costs and organisational frictions, but ultimately generate innovation enhancing returns. This supports a contingent resource based logic, aligning with arguments in organisational theory that emphasise time-lagged and path dependent effects in capability development (Teece, 2007). This study thus contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how sustainability investments translate into firm-level innovation outcomes.

Second, we extend the literature on organisational ambidexterity by theorizing ESG performance as a strategic antecedent that simultaneously influences exploitative and exploratory innovation (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Xing, Huang & Fang, 2025). While prior studies have primarily examined structural configurations and leadership capabilities as enablers of ambidexterity (Jansen, Van den Bosch & Volberda, 2006; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008; Randhawa et al., 2021), limited attention has been given to how external governance mechanisms, particularly those associated with ESG initiatives, influence the composition of firms’ innovation portfolios. By integrating stakeholder theory and institutional theory, the findings suggest that ESG orientation provides firms with the institutional legitimacy and stakeholder endorsement necessary to balance short term optimisation with long-term adaptability (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013). This reconceptualization positions ESG not merely as a constraint or risk mitigation mechanism but as a strategic lever for dynamic capability deployment.

Third, we contribute to the emerging literature on the micro foundations of ESG based value creation (Barney & Felin, 2013; Hafenbrädl & Waeger, 2017) by unpacking the mediating mechanisms through which ESG impacts innovation. Specifically, the empirical analyses demonstrate that firms with strong ESG performance experience lower financial constraints and exhibit higher risk-taking propensity—two organisational conditions that are foundational to innovation (Cucculelli & Bettinelli, 2015), yet are rarely integrated into ESG influenced innovation models. These results challenge the view of ESG as a primarily symbolic or reputational tool and instead highlight its tangible role in shaping resource allocation and strategic decision-making within the firm. This mechanism-based explanation introduces granularity to the existing literature on sustainability performance relationships and underscores ESG’s embeddedness in internal organisational processes.

Fourth, the findings contribute to the institutional logics perspective by examining how the relationship between ESG and innovation is shaped by external contingencies, including government subsidies and market competition (Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury, 2012; Xing, Huang & Fang, 2025). While prior studies have typically emphasised the enabling effects of public policy (Delmas & Toffel, 2008) and competitive intensity (Porter & van der Linde, 1995), the moderation analysis reveals a more complex interplay. Excessive external pressures, whether from regulatory incentives or market dynamics, can dilute the firm’s internal ESG-driven logic, resulting in strategic ambiguity or symbolic compliance. This insight contributes to the literature on institutional complexity and hybrid organising by highlighting the potential for misalignment between external institutional demands and internal sustainability-oriented strategies (Greenwood et al., 2011; Shabbir, 2025). This offers a theoretical lens to explain why ESG initiatives may fail to produce expected innovation outcomes under certain boundary conditions.

Managerial implicationsThe findings offer critical insights for corporate executives, sustainability managers, and policymakers striving to balance environmental responsibility with competitive innovation strategies, particularly in high-tech, regulation-intensive industries such as NEVs.

For corporate managers, the U-shaped ESG innovation relationship underscores the importance of strategic patience and alignment. Early stage ESG adoption may divert resources away from R&D and innovation activities owing to compliance costs and organisational restructuring. However, once a critical capability threshold is surpassed, ESG practices begin to generate innovation dividends by enhancing stakeholder trust, reducing risk exposure, and facilitating strategic partnerships (Bhandari, Ranta, & Salo, 2022; Hart & Dowell, 2011). Managers should therefore treat ESG not as a short-term cost centre but as a long-term enabler of ambidextrous innovation, capable of reconciling operational efficiency with radical transformation.

In practice, ESG oriented firms should actively monitor and manage internal readiness conditions, such as capital liquidity and risk tolerance, to optimise innovation outcomes. Investment in ESG reporting systems, governance reforms, and stakeholder engagement mechanisms can bolster transparency and signal credibility to investors and partners, thereby easing financing constraints and reducing perceived innovation risk (Ioannou & Serafeim, 2015). These adjustments are especially vital when pursuing exploratory innovation, which often requires more flexible organisational structures and higher tolerance for failure.

Furthermore, the role of government subsidies and market competition as double-edged swords presents an important strategic consideration. Although these external forces can incentivise innovation, their interaction with high ESG performance may lead to diminishing marginal returns if not well calibrated. For instance, over-reliance on government subsidies could shift managerial focus from long term innovation capacity building to short term grant compliance or rent-seeking behaviours. Companies should therefore develop internal evaluation mechanisms to ensure that external incentives reinforce, rather than replace, intrinsic innovation motivations.

For policymakers, the findings suggest a shift from blanket subsidy strategies to differentiated support schemes. Incentives should be conditional upon clear ESG milestones and innovation outcomes, with monitoring systems in place to discourage symbolic ESG adoption. Moreover, the observed ownership heterogeneity implies that state-owned firms may require governance reforms or incentive redesign to better integrate ESG principles into their strategic core. This could include revising performance appraisal criteria, granting managerial autonomy in innovation decisions, or creating hybrid incentive structures that reward both compliance and creativity.

The international relevance of these insights is evident. In developed economies with relatively mature ESG infrastructure, the Chinese case serves as a mirror, highlighting the risks of over-standardisation and greenwashing. Firms in such contexts should guard against box-ticking approaches to ESG and instead cultivate strategic capabilities that enhance learning, adaptability, and stakeholder co-creation (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006; Nidumolu, Prahalad & Rangaswami, 2009).

Ultimately, the study advocates for a systemic integration of ESG and innovation strategy, where sustainability is not an external add-on but a core lens through which firms design and execute their innovation portfolios. By clarifying the trade-offs, thresholds, and institutional contingencies involved, these findings help organisations navigate the sustainability innovation interface with greater precision and purpose.

ConclusionsThis study explores how ESG performance influences exploratory and exploitative innovation in the context of China’s NEV industry. We identify a nonlinear U-shaped relationship, where initial ESG engagement imposes adjustment costs and suppresses innovation. However, beyond a critical point, it significantly enhances innovation capabilities. Through mediation analysis, we demonstrate that ESG performance improves firms’ access to financial resources and increases their willingness to undertake risk, which are crucial drivers of innovation. In addition, the moderation analysis reveals that both government subsidies and market competition can dilute the positive effects of ESG at higher performance levels. Additionally, ownership characteristics play a critical role, with SOEs facing more constraints in leveraging ESG for exploratory innovation owing to institutional rigidity and lower responsiveness. By integrating insights from stakeholder theory and institutional theory, this research highlights ESG as a dual-force mechanism. It acts both as a constraint and a catalyst, depending on the timing and contextual conditions. These findings contribute to a more dynamic understanding of how sustainability commitments shape innovation strategies.

Limitations and future researchSeveral limitations provide avenues for future inquiry. First, the current analysis does not distinguish between green and non-green innovation, which limits the ability to evaluate ESG’s environmental relevance. Second, while financing constraints and risk-taking serve as mediators, other mechanisms such as dynamic capabilities or innovation culture may also play significant roles and deserve further attention. Third, the exclusive use of the Huazheng ESG rating system may restrict the robustness of the findings. Incorporating alternative ESG metrics and primary data would improve measurement validity. Fourth, the sample is limited to listed firms in the NEV sector, which constrains the generalisability of the results. Future research should consider a broader range of industries and institutional contexts to validate and extend these insights. We hope this study encourages continued exploration into the complex relationship between ESG engagement and corporate innovation, particularly under varying institutional pressures and organisational structures.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHuanyong Ji: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jing Huang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Keke Sun: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis. Zeyu Xing: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization.

The authors would like to thank the editors and the anonymous review team for their insightful comments and suggestions that immensely helped to improve this article. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 72102020) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Nos. 23CJY070).