The European Union’s circular economy (CE) policy aims to foster closed-loop systems that reduce waste and resource use, yet its practical implementation remains limited. Open innovation (OI)—the cross-organizational sharing of knowledge and collaborative problem-solving—offers a promising but underexplored pathway to accelerate circular economy transformation, particularly by enabling collaboration among diverse actors. This study addresses a critical research gap by examining how OI instruments mobilize multi-actor collaboration for circular economy goals, using an in-depth case study of Fab City Hamburg (FCH)—a pioneering initiative combining OI and CE principles to promote local, open, and circular production. Drawing on qualitative analysis of two circular open labs within FCH and integrating insights from transition theory with the small wins governance framework, we offer original insights into the dynamics of open innovation for circular economy transformation. Our findings reveal that open innovation instruments foster spreading and partial deepening of circular practices by supporting learning, experimentation, and community-building. However, significant barriers to broadening collaborations persist, including conflicting understandings of openness and circularity, organizational asymmetries, and unstable funding structures. The study contributes to the literature on CE and OI by offering a multi-actor, governance-oriented perspective on collaborative circular innovation. We highlight both synergies and frictions in applying OI to CE contexts and provide practical guidance for policymakers, intermediaries, and practitioners seeking to foster collaborative innovation and overcome barriers in circular economy transitions.

The European Union’s circular economy policy has become a driving force for sustainable transformation actions, especially in urban and regional contexts, emphasizing a shift toward closed-loop systems that minimize waste and resource use (Bahn-Walkowiak & Wilts, 2023; Fratini et al., 2019; Kębłowski et al., 2020). However, the transition to a circular economy (CE) has faced criticism for its slow pace and limited practical adoption (Corvellec et al., 2022; Kirchherr et al., 2023; Williams, 2019). Open innovation (OI), the collaborative sharing of knowledge across organizational boundaries (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014), offers a promising approach for accelerating this transformation. OI encourages business model innovations that integrate social and environmental concerns, moving away from isolated, proprietary methods. Concepts such as open circular innovation or collaborative circular-oriented innovation build on this, advocating a more collaborative approach to circular economy practices (Brown et al., 2019; Eisenreich et al., 2021). Proponents argue that open innovation holds significant potential to support the sustainability transformation, making it a valuable framework to consider within circular economy policy.

While the convergence of open innovation and circular economy is gaining attention, several critical gaps in the literature remain. First, existing studies of collaborations on circular economy and open innovation mostly take a product-based focus (Jesus & Jugend, 2023). Second, for circular economy, the complex roles and interactions among stakeholders within these initiatives—essential to understanding their collaborative dynamics—are often underexplored (Julia Köhler et al., 2022; Schagen et al., 2024; Schultz et al., 2024). Where OI and CE collaborations are considered, value and motivation effects for stakeholders are described but concrete mechanisms for furthering the work more broadly are lacking (Coppola et al., 2023; Eisenreich et al., 2021; Ozdemir et al., 2023; Perotti et al., 2025a, 2025b; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022). Thus, the potential contribution or conflicts with the overall circular economy transition remain undefined.

In this study, we ask how open innovation instruments can mobilize both private and public organizations in their pursuit of circular economy goals. To explore this question, we focus on the Fab City Hamburg Association (FCH), an initiative combining open innovation and circular economy within a vision of local, circular, and open production in Hamburg. We identify two circular open labs within this project as examples of incremental but concrete progress, or small wins (Termeer & Dewulf, 2019; Termeer & Metze, 2019), toward an open-source circular economy. These labs exemplify how open innovation practices, adapted to circular goals, can bring diverse actors together. Small wins is a suitable perspective from which to assess the transformative impact of small, grassroots actors and movements, and has been applied in assessments of circular initiatives and innovation processes (Bours et al., 2021; Friedrich & Feser, 2024; Schagen et al., 2024, 2023; Termeer & Metze, 2019). So far, these applications have considered the impacts of individual initiatives, rather than the transformative potential of their interactions (Schagen et al., 2024, 2023).

Applying the small wins governance perspective, we evaluate how open innovation contributes to the advancement of the circular economy transition. We enrich the transition literature at the intersection of circular economy and open innovation and provide implications to address CE through collaborative processes. Our theoretical contribution is through the description and analysis of stakeholder interactions and concrete mechanisms applied in collaborative OI activities, responding to the present gaps in the literature (e.g., Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Julia Köhler et al., 2022; Perotti et al., 2025b; Schagen et al., 2024). The study offers insights for practitioners at the intersection of circular economy and open innovation, for example in local sustainability and innovation initiatives, policymaking, and CE business development. First, we relate the scientific discussion on sustainability transformation and its governance to circular economy and open innovation. We then provide context on the Fab City project in Hamburg and our methodological approach. Key stakeholders in Hamburg’s Fab City network are introduced, focusing on how they integrate OI within circular initiatives. Finally, we apply the small wins governance framework to analyze how open innovation facilitates or complicates the circular economy pathway.

Theoretical positioningThe circular economy (CE) and associated terms, such as circular bioeconomy or circular cities, are an increasingly popular subject of scientific research, of public policy efforts, and of initiatives in the private sector and industry (Kirchherr et al., 2023; Lazarevic & Valve, 2017). However, many have noted the slow progress of the concept at a broader scale (Corvellec et al., 2022; Kirchherr et al., 2023; Williams, 2019). This can be observed in connections to the sustainability transition (Camilleri, 2019; Jesus et al., 2018).

Collaboration in multiple forms and at multiple levels, involving diverse types of actors and consideration of social and ecological cycles in addition to materials and resources, is central to the circular economy transformation (Calisto Friant et al., 2023; Danvers et al., 2023; Schultz et al., 2024; Verleye et al., 2024). Studies of business and economic actors show interest in collaboration for CE and mutual benefits of doing so, although also with trade-offs when it comes to financial exploitation (Brown et al., 2019) or competitive advantage of results (Köhler et al., 2022). Approaches to apply open innovation (OI) to address these challenges in CE have been proposed (Brown et al., 2019; Eisenreich et al., 2021).

Chesbrough and Bogers (2014) define open innovation as a “distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms” (2014, p. 17). Open innovation has been found to support collaboration among firms working to further circular economy efforts (Köhler et al., 2022; Perotti et al., 2025a), especially by enabling co-creation approaches (Jesus & Jugend, 2023), and to improve CE results for products and processes through expanded access to resources (Perotti et al., 2025b). Studies of open innovation contributions to CE within firms and in multi-actor contexts have applied the (natural-)resource-based view and stakeholder theory, focusing primarily on circular business models and value creation (Coppola et al., 2023; Eisenreich et al., 2021; Ozdemir et al., 2023; Perotti et al., 2025a, 2025b; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022). Seeking to describe involved stakeholders, they distinguish between those operating in the supply chain and external to it, who respectively have different motivations and roles in collaborations (e.g., Ozdemir et al., 2023). Those in the circular ecosystem (external) have a higher heterogeneity of sectors and knowledge and are “involved due to their territorial proximity” (Perotti et al., 2025a, p. 401). They act as orchestrators, operating at the ecosystem level to unite various sectoral efforts, and “are fundamental in leveraging OI mechanisms” (Perotti et al., 2025a, p. 402). Such collaborations involve private firms, universities, both non-governmental and governmental organizations, as well as competitor firms and consumers in some cases. But, it has been found that companies lack the necessary skills and, sometimes, willingness to adequately involve externals in open innovation (Eisenreich et al., 2021).

These studies approach CE and OI from a perspective of production-consumption relationships. Actor dynamics within these collaborations are considered from the firms’ perspective to improve products, close loops, scale businesses, and engage customers. Motivations for diverse stakeholders to collaborate feature in discussions of multi-dimensional forms of value, and such studies recognize the integral role of non-business actors, especially policymakers (Coppola et al., 2023; Perotti et al., 2025b; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022). But, despite calling for policy support, there is a lack of clear recommendations for collaborative mechanisms that such external stakeholders should apply. Also, the specific role of open innovation intermediaries in collaboration and their contribution to knowledge and idea transfer remains under-examined (Bigliardi et al., 2021).

Interactions among such stakeholders take place in what the multi-level governance perspective refers to as the niche. Drawing on transition theory (e.g., Grin et al., 2011), our research is grounded within multi-level governance. This concept provides a model for the movement of niche innovations into the socio-technical regime and their influence on the development of new regimes as changes in the socio-technical landscape take place (Geels & Schot, 2007; Geels, 2011; Greer, 2022). Looking broadly at sustainable development and green transition processes, there is an active scientific discussion of how to describe and govern such a transition process on the ground, as well as in national and international policy efforts (Hölscher & Frantzeskaki, 2021; Jonathan Köhler et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2013).

Actors driving innovation and social change can be considered transformation pioneers (Ehnert et al., 2022; Engel et al., 2019; Smith, 2007). These people or organizations act in a value- and goal-oriented way, propel innovation, and forge new paths for sustainable development (Grin et al., 2011). They can be identified through the transformative nature of their actions, which demonstrate and enable changes in practice, values, and norms. They share a combination of characteristics which contribute to their inspirational, motivational, and leadership roles (Engel et al., 2018; Ehnert et al., 2022). However, here, the patterns and mechanisms at play are not described in the broad model and should be the subject of further research (Geels, 2011).

Reviewing modes of governance of transformative change, Termeer et al. (2024) present three approaches towards transformative action to emphasize the trade-offs between the speed of change, its scope, and its depth: Big Plans, Small Wins, and Rule Changes. Unlike multi-level governance’s descriptive model, these archetypes provide a more strategic standpoint to determine and select a transformative pathway suited to the challenge at hand (Termeer et al., 2024). Such perspectives do not limit consideration to single levels or within a certain niche and allow focus to be placed on incremental, on-going contributions of initiatives though their concrete results (Schagen et al., 2024).

Governing the small wins pathway for transformation involves a process by which innovations or initiatives deepen (intensifying or further radical levels of change), broaden (expanding into other fields or sectors), and spread (scaling in terms of number of adherents or practitioners) (Schagen et al., 2023). Actors both within and outside of these initiatives need a stronger understanding of the strategies and instruments that can influence these processes positively and negatively (Schagen et al., 2023), especially related to the mutual interactions of different initiatives (Schagen et al., 2024). Further explorations of small wins strategy holds potential for regional innovation policy, due to the multi-actor and multi-level viewpoints (Bours et al., 2021).

In this study, we outline the extent to which the transformation pioneers within the Fab City movement in Hamburg and their activities can be considered small wins in a transformative sense (Bours et al., 2021; Schagen et al., 2024, 2023; Termeer & Metze, 2019; Termeer et al., 2024). We examine how their application of open innovation contributes to or hinders the deepening, broadening, and spreading of their circular economy transformative actions. The small wins perspective provides a complementary model within which to describe the concrete activities of diverse actors in CE processes, while the collaboration inherent to open innovation offers a rich environment of interactions. We thus explore the role of open innovation to support a multi-stakeholder network in the adoption of CE practices.

Material and methodsThe research presented in this study results from work performed as part of the Fab City Project, Fab City: Decentral, digital production for value creation, in Hamburg from 2021–2024. In a dedicated sub-project, we investigated the governance implications and potentials within the Fab City movement in Hamburg. The subjects of our research were the Fab City Hamburg Association (FCH) and the circular open labs developed within the framework of the project.

The Fab City Global Initiative is a network of cities and regions united in their commitment to promote the Fab City principles and to achieve the goal of almost completely local production (Diez, 2016). Both circular economy and open innovation are intrinsic to the Fab City vision (Diez, 2020). Aligned with the Fab City Global Initiative, the FCH envisions an urban economy in 2054 that has become circular and in which local production fully meets the needs of local consumption (Fab City Hamburg, 2024b). Hamburg became the first German city to join the initiative in 2019. The Fab City project supported the implementation of several open labs, which experiment with different local, decentralized production methods and which focus individually on specific production materials and processes. Two of these labs, the Open Lab Textile and Open Lab Plastic, were founded with expressly circular motivations and directly address circular and open production concerns in their work. Hamburg, therefore, represents a forerunner case for the Fab City in Germany. It provides a model context of newly developing initiatives, growing communities of practice, and strategic alignment with local policy.

In order to identify the transformation pioneers (Engel et al., 2019; Ehnert et al., 2022) for circular local production in the FCH context, we drew on observations in the labs and at circular economy and Fab City-related events in Hamburg, as well as on four iterative in-depth interviews with the lab managers (two per lab group). This resulted in a set of 10 pioneers from civil society, science and research, administration and politics, and industry. These pioneers were identified based on their transformative actions in the Hamburg context and via nominations by the other actors as drivers or motivators for the FCH in general (Engel et al., 2018). A further set of semi-structured interviews were then conducted with each of the pioneers to explore their motives, goals, and relationships with each other, as well as the supporting and hindering factors of their work. Focusing on open innovation activities, the key elements of the interviews were the elaboration of the roles of the pioneers, which open innovation instruments they developed or were available to them, and how they apply these and collaborate with others in this process.

We analyzed the interviews using qualitative content analysis (Mayring & Fenzl, 2014, 2019) to identify the available instruments, capabilities, and factors that influence the transformation process. Instruments refer to all the means or actions that governmental and non-governmental actors can apply in the attainment of their goals (Bucci Ancapi et al., 2022). These instruments generally belong to three groups: formal, economic, and informal (Fröhlich et al., 2014). For the investigation of open innovation instruments, we focus particularly on the informal instruments that have been developed within the FCH, as identified in the interviews.

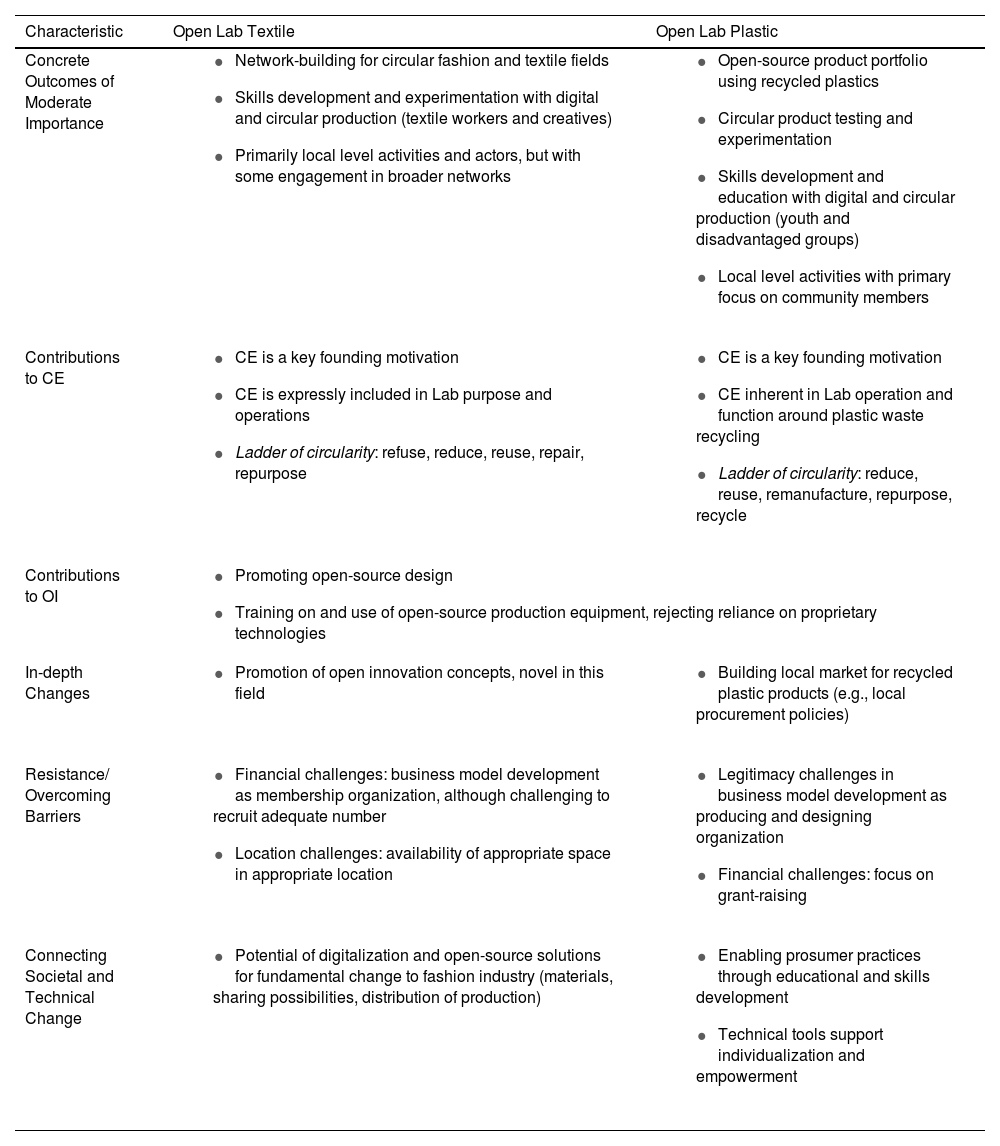

ResultsOpen labs as small wins for CE/OIFollowing the characteristics presented by Termeer and Metze (2019), we identify the Open Lab Textile and Open Lab Plastic as small wins (Table 1). Both have led to concrete outcomes in terms of physical production and in creating and strengthening new networks and collaborations in their target communities. They work at the local level and are embedded in their respective fields within Hamburg, while promoting and enabling changes in practice in these fields that can be considered truly radical (Loorbach, 2022). The labs offer spaces for experimentation with the reorganization of linear consumption systems into circular and prosumer models.

Elaboration of small wins characteristics of Open Lab Textile and Open Lab Plastic for OI and CE (adapted from Termeer & Metze, 2019).

As Table 1 shows, while focusing on different materials and target groups, both labs demonstrate concrete outcomes and in-depth changes, physical and relational, for circular economy and open innovation transformation in Hamburg. Despite facing barriers, they have established themselves in local, regional, and national CE and OI communities. The labs represent an essential element of the FCH’s future envisioned small scale, distributed, local production network. In their work, they interact with each other and further actors (government, businesses, etc.) who also seek to push the Fab City movement out of the niche and into the mainstream. We next address who, in addition to the labs as small wins themselves, are the actors driving this movement in Hamburg, the transformation pioneers, and what their motivations are with respect to circular economy and open innovation.

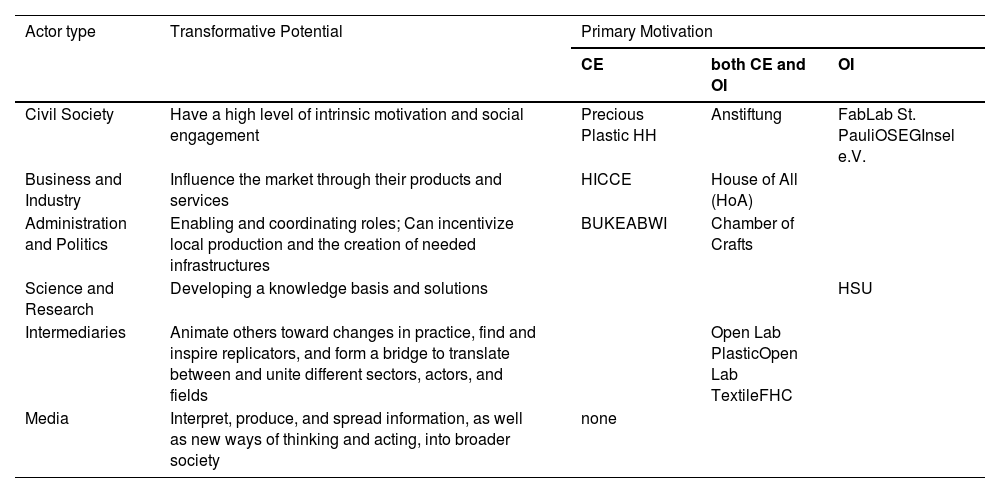

Transformation pioneers according to their motivations toward CE and OIThe transformation pioneers identified in FCH belong to six different stakeholder groups (Heyen et al., 2018; Moss, 2009). Uniting the groups, on one level, are their shared understandings of the economic, political, and social conditions. We observed high personal commitment despite differing contexts of their work: temporary, project-based work for civil society actors and, for governmental institutions, the negotiation of multiple tasks as part of longer planning cycles. Notably, and as shown in Table 2, the motivations for their engagement in the FCH differs among the transformation pioneers, related to their respective interest and commitments to circular economy, open innovation, or both.

Transformation pioneers in the FCH movement and their primary motivations related to CE and OI.

Table 2 highlights that, within their respective groups, the transformation pioneers are subject to conditions that frame their range of actions, their primary motivations, and their transformative potential. For example, in the organized civil society group, the local Hamburg organization Precious Plastic HH deals with the processing of plastic waste and is primarily circular economy-motivated. Insel e.V., which advocates for and supports the integration of socially disadvantaged people, and Fablab St. Pauli, a community space for making, hacking, and innovating, are primarily open innovation-motivated. The same is true for Open Source Ecology Germany (OSEG), a national network for those working with or developing open-source methods and tools. Also at the national level is Anstiftung, a foundation that promotes social projects such as open workshops, community gardens, and repair initiatives, and which combines CE and OI motivations. Uniting these pioneers is their intrinsic sense of purpose and motivation for their causes and well-developed social foci and outreach efforts.

Business and industry pioneers try to influence the transformation of the market through their products and services, focusing, above all, on circular economy implementation. The Hamburg Institute for Innovation, Climate Protection, and Circular Economy (HIICCE), a subsidiary of Hamburg’s waste management company in cooperation with Technical University Hamburg, works on sustainable resource management. The House of All (HoA), a company that produces textiles sustainably, locally, and open-source, focuses particularly on CE in fashion. We observed close cooperation among actors in business, industry, administration, and politics. The latter can create incentives for local production and provide infrastructure. Further, they take on an enabling and coordinating role (Eneqvist & Karvonen, 2021). Here, the primary transformative interest lies in the implementation of the CE. The Ministry for Environment, Climate, Energy, and Agriculture (BUKEA), the Ministry for Business and Innovation (BWI), and the Chamber of Crafts (Handwerkskammer) have set up dedicated departments for CE concerns. However, they operate independently and pursue their own circular economy goals. Open-source innovations are considered by these actors to be too idealistic.

The Helmut Schmidt University (HSU) represents the science and research actor group, with a large and long-standing team of about 50 employees in the Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering who form the core of the Fab City Project. External research funding allows them to work without considering commercial success, and open innovation is their primary goal. They work to create a knowledge base for distributed and decentralized production as a basis for the societal and economic transition, and develop related solutions and innovations, such as open-source production machinery.

Intermediaries at the nexus of science, business, and civil society in Hamburg are the Open Labs Plastic and Textile and the FCH itself. The open labs host practical experiments with concrete outcomes in the area of CE and OI, which can be imitated and encourage others to change their behavioral practices (WBGU 2011). As intermediaries, they also form the interface between different sectors, actors, and fields of action (Kivimaa et al., 2019). The FCH members include actors from across the various groups, including some of the listed transformation pioneers as well as other organizations (Fab City Hamburg 2024a). No transformation pioneers were identified from the media and press group, which highlights a lack of actors who carry the new ways of thinking and acting into wider society.

While the pioneers described here all work within the broader Fab City movement in Hamburg, their understanding of the relative importance of circular economy and open innovation and their motivations in these respects clearly differ. The subsequent elaboration of their dynamics describes their concrete approaches to this work and their mutual collaborations.

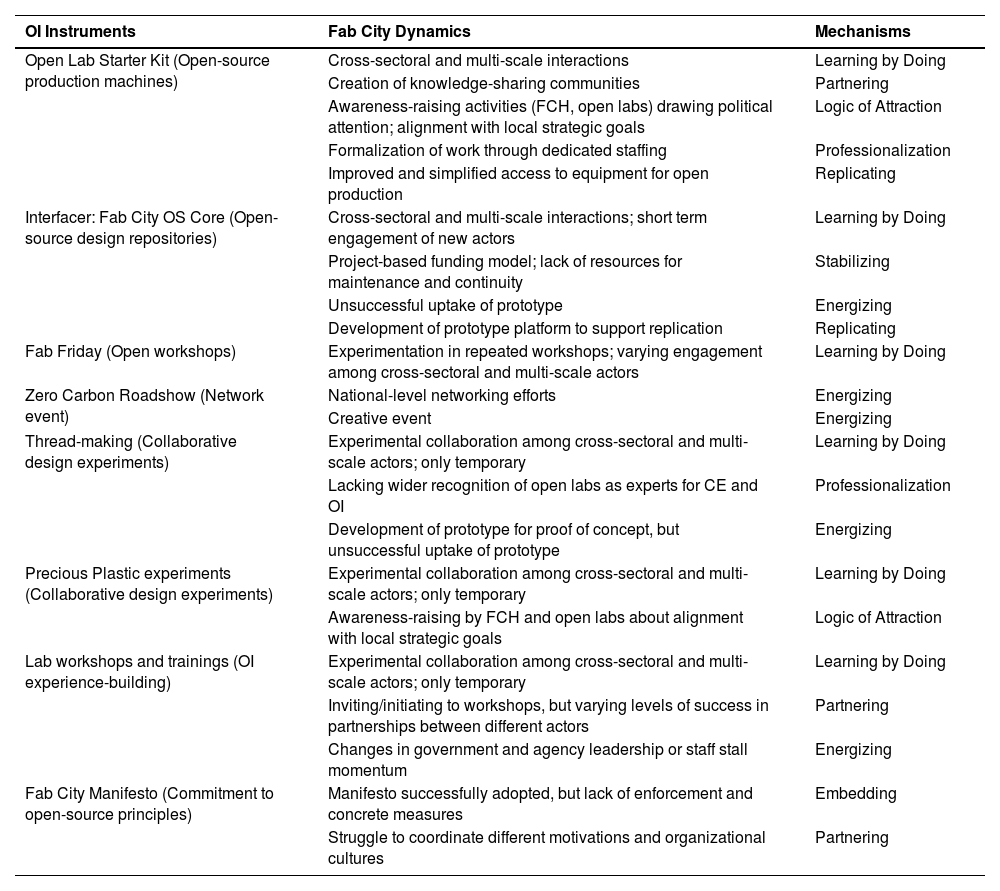

Multi-actor dynamicsFrom the interviews, we identified a set of OI instruments the transformation pioneers apply as part of their work. These instruments are the key programs, events, or tools the pioneers use to engage their internal as well as external stakeholders and integrate their knowledge and expertise. The OI instruments range from open-source design and building plans for machines to participatory workshops to a Manifest. In this section, we apply the propelling mechanisms of the small wins framework (Schagen et al., 2024). Research into the activities within small win circular initiatives has identified positive feedback loops which strengthen the initiatives through propelling mechanisms (Schagen et al., 2023). These mechanisms include learning by doing, partnering, stabilizing, embedding, logic of attraction, professionalization, energizing, and replicating. They summarize processes of interaction among diverse actors from the initiative itself, networks in the field, external public or private institutions, and the broader community. To elaborate the mechanisms present in the Hamburg case, we connect the pioneers of the FCH with their actions and interactions specifically in the application of these OI instruments.

Not only the implementation of the instruments but also their initial co-development and future maintenance involved collaborations among the pioneers—although with varying levels of success. In Table 3, we describe the dynamics present in the application of each instrument and assign them to the corresponding propelling mechanism. Here, we do not describe only activities organized by the small wins labs themselves. We also include the interactions of the transformation pioneers among each other which contribute (or not) to the growth and success of the movement and progress toward their circular economy and open innovation goals. The categorization by propelling mechanism relates these activities to modes of transformative impact for the CE transformation, though the dynamic itself may not have a positive outcome.

Fab City actor dynamics and their relation to the propelling mechanisms of the small wins framework (adapted from Schagen et al. 2024).

As Table 3 shows, learning by doing is strongly prevalent in the Fab City movement, as various pioneers have collaboratively developed and applied multiple OI instruments to support on-going experimentation and integrate new learnings. However, the collaboration across sectors directly in the doing, such as with local authorities or business partners, is made more difficult by the lack of consistent formats for such actions. Isolated attempts took place, but could not be continued due to lack of funding, time, resources, etc. Replicating, such that same or similar approaches or actions arise, is another essential mechanism to progress toward circular economy. The OI instrument Open Lab Starter Kit by HSU has enabled an easier process of replication by simplifying access to equipment for local, open, digital production. The use of these machines does not support collaboration between the actors, however. They do not collaborate on joint production processes, nor must production carried out with the machines be circular. Conceptually, the open-source repository of the Interfacer project would support replication of specific, possibly circular solutions, but lacks the supporting resources and infrastructure for the needed promotion and management.

Especially through OI instruments like design experiments and lab workshops, civil society actors have created mutually beneficial knowledge-sharing communities through exchange about their experiences. Cooperation and sharing between actors is seen in the partnering mechanism. With the Open Lab Starter Kits, the HSU shares personnel, technical knowledge, and capacity with open labs. More difficult was the partnering between various actors in the open labs and the Chamber of Crafts. Workshops and trainings had only partial success. Here, conflicting organizational goals and agendas prevented further partnering. Due to limitations in organizational structure (most projects are temporary) and legal or institutional barriers, most OI instruments remain informal and cannot be adapted in administrative processes (e.g., procurement). Therefore, embedding, the formalization and integration of the OI instruments into agendas, policy, and practice, is a particular challenge. Even though the City of Hamburg and the FCH, as well as the open labs, have signed onto the Fab City Manifesto, there is no specific format for implementation or enforcement of such a framework agreement. Primary drivers here are the Chamber of Crafts and the FCH, who struggle to coordinate their differing motivations and organizational cultures.

Cooperation for funding between the FCH and national and city-level agencies led to the creation of staff positions for researchers at the HSU and the open labs. This demonstrates a high degree of professionalization. In this manner, recognition was achieved with the inclusion of Fab City concepts in the Hamburg government coalition agreement. There is a narrative of success around the concept of creative labs and local production driven primarily by awareness-raising by the FCH. The open labs have also gained some notice among political and administrative actors due to alignment with local strategic goals. FCH is seen as an expert for circular economy and open innovation and is a frequent invited contributor to events or working groups with political and administrative actors. But this is not the case for the open labs themselves, which reveals variations in the mechanism of logic of attraction among actors. Rather than with policymakers, the labs’ interactions build logic of attraction in maker communities and network organizations, for example through the OI instruments of Precious Plastic experiments and thread-making. The prototypes they develop, alongside the Open Lab Starter Kit, help build momentum. Networking efforts at national level by the civil society actors both bring in external ideas and promote local results, for example through the Zero Carbon Roadshow. Such frequent events with different scales and target groups support energizing around the Fab City vision. Still, momentum is inconsistently maintained, for example with city departments after changes in government and leadership, staff, or strategic focus of certain agencies.

The prototypes did not experience successful uptake and use in the longer-term. The project-based funding models of most of the actors is a major barrier for the stabilization of the Fab City movement. Few collaborations have been able to build solid routines and strong continuity. Most projects have the goal to create and test new innovations and ideas, such as the Interfacer platform or the Open Lab Starter Kit, while no resources are allocated for maintenance and further development. Thus, new actors and institutions are reached and briefly engaged, but the long-term resilience of the concept is not improved.

In all cases, collaborations involve the transformation pioneers in various capacities. Classifying these through the propelling mechanisms reveals that these collaborations do not uniformly support the achievement of the mutual transformative goals. Underlying the shared work are gaps that prevent the mechanisms’ propelling functions. For example, partnering and learning by doing are visible in almost all OI instrument implementations, but lack successful stabilizing, embedding, and replicating corollaries. Also, dynamics related to logic of attraction and professionalization have varying outcomes for different pioneers: FCH and HSU on the administrative and political level and the labs within their own fields but not beyond. Considering the small wins transformation pathway, these results imply weaknesses in the necessary trajectories of deepening, broadening, and spreading.

DiscussionThis study uniquely applies the small wins framework to interactions among multiple actors (labs, civil society, business, academia, and government) within a localized open innovation ecosystem (Fab City Hamburg). It shows how small wins (like open labs) are not just stand-alone successes, but nodes within a network of interdependent transformation pioneers, generating both enabling and constraining dynamics. This provides a more systemic view of transformation in the circular economy context.

To address the identified gaps in research and literature, the study extends existing studies of collaborations on circular economy and open innovation (Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Julia Köhler et al., 2022; Perotti et al., 2025a, 2025b) by shifting the lens to collaborative processes, OI instruments, and social-organizational infrastructure. Many CE-OI studies emphasize technological innovations within firms or supply chains (Coppola et al., 2023; Eisenreich et al., 2021). They are often corporate-focused and disconnected from local, community-based circular economy dynamics. This study departs from a product-centered view, instead bringing attention to the process and system innovation dimension of CE and deepening understanding of collaborative complexity.

We go beyond the existing stream of literature (e.g., Bigliardi et al., 2021; Jesus & Jugend, 2023; Julia Köhler et al., 2022; Ozdemir et al., 2023; Perotti et al., 2025a, 2025b; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022) to explore further the complex roles and interactions among stakeholders within CE and OI initiatives. The different motivational typologies and interactions of the transformation pioneers reveal complex multi-actor dynamics in the FCH. The propelling mechanisms trace the application of the OI instruments within the FCH network and broader community. In this section, we turn to the contribution of open innovation collaborations to the larger circular economy transformation by discussing the impact and challenges of the OI instruments. The small wins framework describes three trajectories by which the transformation can further develop: spreading, deepening, and broadening (Schagen et al., 2023). First, we map and describe the impacts of the OI instruments applied in Hamburg in the small wins trajectories. Subsequently, we discuss frictions that arise from combining OI and CE principles.

Impacts on small wins trajectoriesWe apply the trajectories of the small wins perspective as follows: (Schagen et al., 2023; Termeer et al., 2024)

- -

Spreading describes the dissemination of the Fab City idea to other actors and locations: the growth of the movement.

- -

Deepening is about strengthening the intensity and level of change: improvements to the capacity, quality, and level of innovation of concrete results.

- -

Broadening refers to the integration of other sectors and stakeholders: recognition and uptake by those in other fields and functions.

- -

Under their premise that fast, broad, and deep changes are “virtually impossible” to achieve at the same time due to their mutual and hindering interactions with each other, Termeer et al. (2024, p. 2) describe the small wins pathway as one in which quick and in-depth changes (small wins) are implemented but struggle to achieve broader scope.

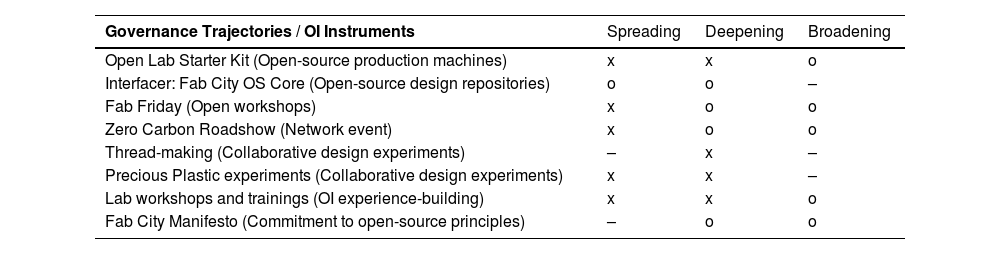

Based on the potential of open innovation to support collaboration and knowledge transfer (Bigliardi et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2019), previous research implies that OI instruments could be supportive of the small wins transformation pathway. Especially relevant to the broadening and spreading trajectories are the open-source principles of the open labs. Deepening, with respect to the research-driven lab structure, could also be supported. Table 4 shows that OI instruments have been applied within the actions and interactions of the transformation pioneers corresponding to all three trajectories. This section elaborates for each trajectory the extent to which open innovation strengthened the collaboration of open labs in the multi-stakeholder network and highlights weaknesses of open innovation applications for circular economy transformation in these respects.

Impacts of the OI instruments in CE collaborations: x - effective implementation; o - ineffective implementation, - no implementation.

It is in spreading, in the growth of the movement, that we see the most effective contribution of OI instruments. Through the uptake of the Open Lab Starter Kit and the proliferation of hands-on workshops, design experiments, and network events, the level of engagement and number of people and organizations participating in the topics of circular distributed production have increased. These instruments contributed to learning by doing and energizing. They have also gained the attention of political and administrative actors, who recognize the alignment with local goals through the Manifest. Nevertheless, while project-based funding has allowed for professionalization by several actors in the movement, the dependence on this time-limited financial support negatively impacts the stabilization potential. For example, the Interfacer project developed an open-source platform (Fab City OS Core) to share and promote the replication of specific solutions, but the necessary support resources expired with the end of the project. In other cases, the level of attention and participation varies with the type of event, for instance thread versus plastic design experiments. Therefore, the success of such instruments was also related to the topic or material context and not only the format itself. This is where the highest positive impact of a multi-actor dynamic emerges. The open innovations stimulate the movement to form synergies and spread the idea of a circular economy. Support from networks such as OSEG or Anstiftung helps to replicate the Fab City concept in other locations, but the infrastructure for systematic dissemination remains limited.

On the deepening trajectory, we see mixed results from the application of the OI instruments. In particular, design experiments and lab workshops push forward the depth of the innovation performed in the larger Fab City community and highlight what is possible in the future, contributing to energizing. The Open Lab Starter Kit and its promotion support the deepening process by demonstrating the potential to move from open-source product to open-source means of production, in alignment with Fab City goals. These are all well-represented in the learning by doing and professionalization mechanisms. Other instruments, such as Fab Friday and Zero Carbon Roadshow were not successful in spurring new or deeper innovations. At the same time, there are challenges in stabilization, particularly in the long-term commitment to development of the prototypes developed. Contributions to partnering and logic of attraction can be seen in the use of and feedback to the Starter Kit by different actors and in the cooperation between FCH and government agencies to fund and support research. However, no successful process of embedding could be observed from the OI instruments. Disparate motivations among the actors, such as FCH and the Chamber of Crafts, make these processes even more difficult. Thus deepening, when observed with the OI instruments, happens primarily within individual pioneer’s organizations or thematic fields and not across sectors.

Despite the potential open innovation implies, we see the most significant gaps in the impacts of the OI instruments in Hamburg in the broadening trajectory. Here, frictions arise in the multi-actor dynamics through the combination of open innovation with circular economy principles. The partnering mechanism was observed in several OI instruments, but the partnerships themselves often experienced barriers and conflicts. Although workshops and networks have been established with various stakeholders, cooperation is often hindered by their different agendas. Where workshops and events are successful in energizing and learning by doing, they do this primarily within the Fab City community (spreading), without attracting participation of external groups (broadening). One example is the difficulty of reaching traditional craftspeople and businesses, despite efforts in partnering specifically in this field. Similarly, replication efforts, such as the Open Lab Starter Kit, facilitate technical implementation among makers, but do not create sustainable cooperation between stakeholders of different types. In addition, the weak representation of embedding mechanisms hinders progress. Even though the Fab City Manifesto provides a theoretical basis for cooperation, there are not sufficient concrete implementation strategies. It is important to note, as well, that the media actor group is missing from the transformation pioneers in the Fab City Hamburg. This group plays a major role in outreach and engagement of wider communities and sectors. It was, thus, not possible to examine how the OI instruments were experienced and applied by this group.

Challenges of OI instruments in CE transformationThe investigation of the application of OI instruments in Hamburg reveals a complex web of roles and interactions among the transformation pioneers. Their efforts to steer and drive the transformation through these instruments spurred collaborative multi-actor dynamics, though not always positive ones. Despite the use of OI instruments in collaboration within multi-actor networks, the differentiation of these applications across the propelling mechanisms in Section 4.3 reveals both gaps and weaknesses in the areas of stabilization, embedding, professionalization, and energizing. Table 4 corroborates these results, describing only partially successful implementation of the OI instruments to support the three small wins trajectories. These findings are in alignment with those of Schagen et al. in their studies of CE small wins (2023, 2024). They see stabilizing as fundamental to all three trajectories (Schagen et al., 2023), but note a trade-off between stabilizing and energizing. The latter mechanism brings inspiration and motivation, but a surplus of new ideas and approaches can also have a destabilizing effect (Schagen et al., 2024). These discrepancies became clear when analyzing the effects of Fab City dynamics in governance processes. Particularly in the area of broadening, the OI instruments are hardly effective. A central problem is that the OI instruments are not always compatible with the ambitions and agendas of the different actors. As a result, they do not find the necessary acceptance to effectively support a transformation to a circular economy.

Firstly, this could be due to the different perceptions that the actors have of CE and OI, which leads to conflicts of objectives and interests. Examples of this mismatch can be seen in the transformation pioneers’ motivations: BWI sees circular economy as an economic process first, while Anstiftung aims for a circular society. Precious Plastic HH pursues local resource management with local citizens as the primary target, while BUKEA focuses on recycling resources for large companies, such as sustainable growth at Airbus. These different perspectives on the circular economy make it difficult to find common ground. Opinions on open innovation are just as diverse. The Chamber of Crafts argues that open is not synonymous with free or amateurish but encompasses professional craftsmanship and brand-independent reparability. The Fablab St. Pauli defines open as freely accessible blueprints. OSEG and House of All understand radically open to refer to collaboration under a Creative Commons license and campaign to radically open up every area of society. Actors from civil society organizations have a broader and more radical view of circular economy and open innovation than many state authorities, and they prefer to use the term open circular society instead of circular economy. These differences in interests and objectives contribute to the complexity of the collaboration.

Secondly, the actors have different organizational structures. Associations, private companies, and public authorities are subject to different requirements. While public authorities have access to funding and secure jobs, research projects and intermediaries are often dependent on third-party funding. Organized civil society projects, such as non-profit associations, depend on their paying members and rely heavily on voluntary commitments. In addition, the actors are subject to different temporal regimes. The predictability of research projects that are dependent on third-party funding differs considerably from the agility of companies, who can react to changes at short notice. State authorities, on the other hand, work according to election periods. These different timeframes lead to asynchronous working methods that are difficult to reconcile. Such structural concerns exist in a negative feedback loop with the implementation of stabilizing, embedding, and partnering mechanisms. Internal mechanisms in these areas are lacking, which threatens the commitment and consistency of these mechanisms applied externally.

ConclusionsIn this study, we asked how OI instruments can mobilize both private and public organizations in their pursuit of circular economy goals. We considered the roles of public, private, and intermediary actors to contribute to the research gap on their specific potentials in the OI and CE transformative context (e.g., Bigliardi et al., 2021; Coppola et al., 2023; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022). We base our analysis in transition theory, particularly the multi-level perspective (MLP) on socio-technical change, situating OI/CE initiatives within processes of innovation and regime transformation. Recognizing the limitations of MLP in explaining multi-actor dynamics, the study drew on the small wins governance framework to discuss how incremental yet transformative actions can generate broader systemic shifts. Focusing on the specific mechanisms, the study deepened the understanding of the multi-actor dynamics, in order to elaborate the synergies and frictions that can arise from combining open innovation with circular economy principles.

We find that OI instruments can catalyze knowledge-sharing practices and foster collaboration among multiple actors, enhancing the potential for transformative change toward circularity as small wins. The relational dynamics among the participants in the network are promoted by OI in many places. But, the open innovation tools are not always suitable for the ambitions and agendas of the various stakeholder groups. Nevertheless, due to their shared interest in transforming social and ecological conditions, there is a high willingness to collaborate and experiment with unconventional formats within all actor groups. The OI instruments in use among the transformation pioneers in the Fab City Hamburg support the spreading and deepening trajectories, although with some gaps. OI instruments were not found to be effective in supporting the broadening trajectory. This weakness falls where small wins governance is most challenged. To avoid the risk that the small wins never get off the ground, it is important not just to pay lip service with terms such as open. Instead, it should be questioned how OI instruments can be made more attractive to engage external sectors and actors. This would be an important topic of further research.

The theoretical contribution is an integrative and applied advancement in the understanding of circular economy transitions at the intersection of multi-actor collaboration and governance theory, specifically through the lens of small wins governance pathways and mechanisms. As we examine only the case of the Fab City movement in Hamburg, this study’s insights cannot be directly extrapolated to OI and CE processes in other contexts. Further research should examine open innovation applications among actors in additional local contexts to explore how various differing local conditions or sectoral foci (e.g., Perotti et al., 2025a) impact open innovation efficacy. Also, by focusing on transition pioneers as drivers in the movement, this study does not consider the role of and impact on citizens in open innovation and their uptake of circular economy principles. We welcome studies that examine more closely the role of OI instruments in propelling mechanisms as they relate to society’s integration of circular economy practices.

This study demonstrates that open labs within Hamburg’s Fab City movement constitute small, yet impactful advances—small wins—in aligning open innovation principles with circular economy objectives. By creating physical and relational outcomes, these open labs act as both experimental spaces for diverse stakeholders and have themselves become intermediaries with a network of transformation pioneers, each with unique motivations toward CE and OI. For such small initiatives and intermediaries, this research indicates that targeted outreach both within and outside of their habitual communities is needed. They should consider how the media can play a role. Through such structures, multi-stakeholder networks can better facilitate the mainstreaming of circular principles, embedding them into a broader societal context and fostering a more sustainable future.

For cities and regions aiming to implement CE/OI initiatives, this study implies a more active role for local governments and administrative actors is needed. These actors are traditionally imagined driving big plans and rule change pathways, but they have potential to use modes and methods of governance which are supportive from a small wins perspective. Examples of steering and pioneering roles taken by city administrative actors together with initiatives to support circular economy can be found in, for example, Obersteg et al. (2019) and Christensen (2021). The potential for circular economy initiatives to contribute to broader change is not uniformly recognized by policymakers, however, and may suffer from these actors' attempts to control them or force them into linear, rational evaluation models which do not reflect their strengths (Termeer & Metze, 2019). Open innovation seems to confront similar problems. Considering the strengths of OI instruments in learning by doing and energizing mechanisms, policy and performance evaluation should be more flexible and responsive to changes in direction or content of funded activities over time.

Finally, to highlight some practical implications, we show in this study that the success of the observed combined open innovation and circular economy collaborations hinges on addressing structural and value-based conflicts. Considering the need for clearer recommendations for policy to better engage external stakeholders in open innovation (Coppola et al., 2023; Tapaninaho & Heikkinen, 2022), we propose that policymakers and facilitators should design governance and collaboration frameworks that explicitly recognize and mediate the divergent interests, organizational logics, and timeframes of different actor groups (public, private, intermediary, civil society). For example, formalized dialogue platforms, longer-term partnership agreements, and capacity-building for cross-sector engagement could mitigate misalignments and foster sustained cooperation. Another key insight of the study is the insufficient presence of stabilization and embedding mechanisms, leading to fragmented efforts and temporary outcomes. If local authorities and city administrators aim to replicate initiatives like Fab City Hamburg, they must move beyond project-based open innovation experiments to establish institutional and financial mechanisms that stabilize and embed successful innovations into long-term urban strategies.

Formatting of funding sourcesThe research performed for the preparation of this article was funded by dtec.bw – Digitalization and Technology Research Center of the Bundeswehr, which is further supported by NextGenerationEU.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMerle Ibach: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Kimberly Tatum: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jörg Knieling: Supervision.

We would like to thank our interview partners for their support and their valuable insights.