Industrial robots are essential for improving productivity and optimizing resource allocation. They help to reduce dependence on traditional labor- and energy-intensive manufacturing methods. While promoting industrial automation, industrial robots have become an important technology for achieving green transformation. Using data from 30 provinces in China from the period 2006 to 2019, this paper examines whether industrial robot applications can enhance Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP). We find that industrial robot applications help to promote CTFP. The robustness test indicates that this result is consistent, while the heterogeneity test shows that the effect of industrial robot applications on CTFP is mainly concentrated in labor-intensive industries, as well as in regions with low technical complexity and strong policy support from the local government. The mechanism test reveals that industrial robot applications can enhance CTFP by enhancing technological innovation and improving human–machine matching.

Industrialization and urbanization have led to a sharp rise in greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, triggering global warming, more frequent extreme weather events, and ecosystem imbalances, which seriously threaten the sustainable development of the global economy. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global energy-related CO₂ emissions were approximately 36.8 Gt in 2022 and showed a clear rebound after the pandemic. At the same time, reports from international environmental organizations point out that the current rate of increase in global average temperature far exceeds any period in the past millennium, and biodiversity loss is unprecedented in human history; these changes not only undermine natural ecological balance but also have far-reaching impacts on human health. In response to these challenges, promoting green industrial transformation and the application of low-carbon technologies has become a global consensus.

Driven by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, industrial robots—owing to their unique advantages in energy saving and emission reduction, intelligent manufacturing, and industrial upgrading—are becoming a new core competitive factor in manufacturing (Sahoo & Lo, 2022). The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) reported an average robot density in manufacturing of about 141 units per 10,000 employees in 2021, with recent annual installation volumes commonly in the range of 400,000–500,000 units. The IFR’s World Robotics report also found that by 2023 the global stock of robots in operation had exceeded 4.2 million units. Robots have been deeply integrated into scientific research, industrial production, healthcare, and everyday life. This technology not only plays an increasingly important role in industrial production, the service sector, and daily work, but also demonstrates great potential in environmental protection and sustainable development.

Industrial robots can optimize energy use and reduce waste emissions, facilitate the reconfiguration of production factors to drive green innovation, and help lower firm- and region-level carbon intensity while improving carbon total factor productivity (CTFP) (Guo & Chang, 2024; Qi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023). Existing studies indicate that industrial robots can reduce the use of fossil fuels by improving the energy mix (Liu, 2025). In addition, applications of artificial intelligence have been shown to significantly enhance energy efficiency (Zhang et al., 2025), supporting synergistic emission-reduction pathways between robotics and intelligent technologies. Other research finds that industrial robots significantly reduce consumption-based embodied carbon intensity in multiple countries, with stronger effects in economies that possess environmental technology advantages (Jin, 2024). Therefore, an in-depth study of the impact of industrial robots on carbon intensity and carbon footprint not only has important theoretical value but also provides empirical evidence for promoting green transformation and sustainable development (Li et al., 2025). Based on this, the present paper aims to examine the effect of industrial robot adoption on CTFP and further analyze its heterogeneous effects across industries and regions.

The innovations and contributions of this paper are as follows. First, this study is the first to construct province‑level measures of industrial robot deployment in China using IFR data on installed robots from 2006 to 2019 combined with provincial employment figures. Methodologically, we avoid the coarse practice of using a binary AI proxy and instead employ the actual number of robots—while also accounting for technological progress and labor restructuring—thereby rendering our findings more persuasive and operationally meaningful. This approach overcomes the limitations of previous studies that relied on robot dummy variables or small‑sample cases, enhancing both the comparability and accuracy of robot‑use intensity measures. Moreover, in measuring productivity, we go beyond traditional single‑factor TFP indices by constructing Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP) from capital stock, labor, GDP, CO₂ emissions, and energy consumption. Specifically, we calculate CTFP via a Luenberger Productivity Index combined with a non‑radial directional distance function (BNDDF), which simultaneously captures dynamic changes in output and environmental emissions. Compared with methods that focus on only output or emissions, our measurement framework more comprehensively reflects industrial efficiency differences under a low‑carbon development paradigm, thus enriching the CTFP literature. Second, while existing literature tends to examine the unidirectional impact of robots on either carbon productivity or TFP, it has largely overlooked their joint effect. From the perspective of simultaneously enhancing carbon and labor productivity, this paper innovatively investigates the impact of industrial robots on CTFP. Our empirical results show that, after controlling for macro factors and technological progress, a one‑percentage‑point increase in robot penetration significantly raises CTFP, demonstrating that robotics can help firms boost output while curbing carbon emissions. Importantly, we also uncover heterogeneous effects: robot adoption delivers stronger CTFP gains in labor‑intensive sectors and in regions with robust policy support. This finding departs from many studies that report only aggregate effects, offering policymakers more targeted guidance for industrial upgrading and filling a gap in the analysis of industry‑ and region‑specific impacts. Third, unlike studies that simply test effects using robot counts or dummy variables, we delve into the internal mechanisms by which robots influence CTFP. We introduce R&D intensity and man-machine matching as mediators and develop a mediation‑analysis framework. Our results indicate that increased robot penetration not only directly enhances production efficiency but also indirectly raises CTFP by fostering firms’ technological innovation capacity and optimizing human–robot collaboration. Compared with conventional models, this mechanism analysis clarifies the dual organizational and innovation‑ecosystem optimization effects of robotics, thereby enriching the literature on the economic impacts of industrial robots.

Overview of literature and research hypothesesLiterature reviewImpact of industrial robots on corporate green behaviorThe relationship between the application of industrial robots and corporate green behavior is a key topic in robotics research (Liang et al., 2023). It was found that green finance can effectively stimulate artificial intelligence to contribute to urban sustainable development (Zeng & Zhang, 2024).Some scholars even raise topics related to this issue in the 20th century (Cortés et al., 1999). Protecting the environment has become an essential factor to consider in economic development. The use of robots allows firms to improve productivity while aligning their development with the direction of national development. The technological advances represented by robots can effectively improve productivity (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018) and contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions. These outcomes further increase firms’ application of robots; in some countries and regions with high labor costs, industrial robots can significantly reduce labor costs. Taken together, these factors motivate firms to expand the use of robots. In a study based on micro-firms, the mechanism through which robot applications influence pollution and emission reduction was identified (Guo et al., 2024). The application of robots is found to enhance emissions reduction technologies while optimizing production processes, reducing pollution emissions at the source, and lowering production costs, thereby improving firms’ energy efficiency (Huang et al., 2022).

Factors affecting CTFPCTFP not only measures the efficiency of carbon emissions in a region’s or firm’s production activities, but also reflects the impact of economic activities on environmental sustainability in pursuit of growth. Given that global climate change and environmental sustainability have become important issues, the study of CTFP is of great practical significance. CTFP is a key indicator of production efficiency and environmental conditions; it has thus attracted the attention of many scholars (Jiang et al., 2021; Kuosmanen & Maczulskij, 2024).More importantly, the current literature has been concentrated on the CTFP of firms. For a country as geographically vast and regionally different as China, it is particularly necessary to study the CTFP of each province. Research shows that the factors influencing CTFP include environmental regulations (Zhou & Zhang, 2024), internet development (Ying & Chao, 2023), technological innovation and progress (Liu et al., 2022), financial development (Chen & Ma, 2024), manufacturing aggregation (Goldfarb & Tucker, 2019), and upgrades to the industrial structure (Cui et al., 2022). Other scholars find that differences in the level of development have an impact on CTFP. For example, the carbon productivity of developing countries is generally lower than that of developed countries (Wang et al., 2017). By dividing China into eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions, the study finds that the green total factor productivity in each region shows a convergence trend (Xia et al., 2024).

Impact of industrial robot applications on CTFPIndustrial robots can improve many things through the Internet of Things and big data technologies, such as realize smart management of the production process, optimize production scheduling and equipment maintenance, achieve optimal allocation of production tasks, reduce production bottlenecks, and improve the overall efficiency of the production line. The application of industrial robots is found to promote the greening and intelligent transformation of China’s manufacturing industry, which in turn influences CTFP (Chen et al., 2024). Cross-country studies show that the higher the level of industrial robot application in a region, the higher the total factor productivity (Daron & Pascual, 2019). In the traditional production process, economic efficiency and environment cannot be considered simultaneously, but industrial robots can help to address this dilemma. Therefore, China should vigorously promote its development to realize sustainable economic development and green growth (Gan et al., 2023). Based on the theoretical framework of productivity enhancement driven by industrial robots, robotics is found to effectively increase total factor productivity in industries with high substitutability (Zhang et al., 2024). Moreover, the digital economy plays a pivotal role in promoting China’s new energy transformation and enhancing total factor productivity (Li et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).However, some studies counter with findings that the application of AI can have a negative impact on CTFP. Driven by market forces, AI technology is found to follow a labor-saving development path, which may trigger unemployment anxiety and hinder employment growth and productivity improvement (Wang et al., 2022). Thus, AI may hinder the improvement of CTFP.

Although the existing literature has considered the impact of applying robots in economic activities, the impact of this application on CTFP requires further investigation, which is addressed in this study on work conducted in Chinese provinces. This paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, instead of examining the application of industrial robots in industries or firms, we turn to the penetration of industrial robots in each province. We focus on the disparity in the stock of industrial robots in each province and then study the impact of applying industrial robots on CTFP to provide new ideas for reducing emissions and increasing provincial-level productivity. Second, we consider the multi-faceted economic differences among Chinese provinces, both in terms of total volume and growth rate, as well as differences in per capita income levels. These differences result from a combination of factors, such as geographic location, resource endowment, industrial structure, and policy orientation, which can lead to differences in CTFP across provinces. By taking an inter-provincial perspective, we can thus better reflect the impact of applying industrial robots on CTFP and thus better assess the localized impact. By studying inter-provincial differences, we can promote inter-regional economic cooperation, enhance connectivity, and promote regional integration. The inter-provincial perspective also provides a macro-analytical framework for understanding and solving cross-regional problems, which can help to promote balanced regional development.

Theoretical implicationsAlthough the existing literature has explored the impact of robots on economic activities, their specific effect on Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP) still requires further study. This research provides three main theoretical contributions. First, it directly links industrial automation—particularly the adoption of industrial robots—with green productivity measured by CTFP, thereby integrating the automation literature with the theoretical frameworks of productivity and sustainability. In this way, this paper places robots within the framework of innovation theory, regarding them as embodied general-purpose technologies that catalyze process, product, and organizational innovation, generate knowledge spillover effects, and stimulate endogenous R&D and capability accumulation. At the same time, by adopting CTFP to incorporate undesirable outputs (carbon emissions) into productivity evaluation, this study responds to sustainability theory by revealing how technological change reshapes performance indicators under environmental constraints.Second, this study identifies two core mechanisms—technological innovation and human–machine collaboration—to explain the pathways through which industrial robots influence sustainable productivity. From the perspective of innovation theory, technological innovation explains resource reallocation, complementarities with firm-level R&D and human capital, and capability building. From the perspective of sustainability theory and socio-technical systems, human–machine collaboration frames how work organization, energy-use practices, and the adoption of low-carbon processes co-evolve with technology, thereby achieving the decoupling of economic output from emissions. Third, by employing the Luenberger BNDDF method to estimate CTFP, this paper provides a methodological contribution to the literature on green total factor productivity and eco-innovation theory. This advanced directional distance measure better captures environmentally adjusted productivity dynamics, thus helping to test the theoretical claim that innovation-driven technological change transforms into green efficiency gains in the context of Industry 4.0.

In summary, these contributions link micro-level technology adoption and organizational mechanisms with macro-level sustainable development outcomes, demonstrating that innovation theory and sustainability theory are complementary perspectives for understanding how smart manufacturing drives innovation-led low-carbon productivity growth.

Research hypothesesCompared with the traditional development process(high accumulation, high input, low efficiency, and low output model), the role of industrial robots in improving productivity and gradually realizing the green transition is becoming increasingly obvious. Labor productivity is an important part of overall productivity, and its role in CTFP is also particularly notable. For example, The development of industrial robots significantly enhances labor productivity (Zhao et al., 2024). Industrial robots also optimize production processes by automatically adjusting machines and equipment, making manufacturing more intelligent and efficient (Zhang, 2024). In addition, AI has been shown to revolutionize production processes and reduce emission intensity by improving energy efficiency, lowering production costs, and advancing green technologies (Zhou et al., 2024). It also shows that due to inaccurate operational precision, manual operations cannot fundamentally avoid pollution; when industrial robots replace manual labor, they can achieve sufficient precision to reduce or avoid pollution. While improving their energy efficiency and controlling pollutant emissions, intelligent technologies such as industrial robots can also facilitate the green transformation of other industrial sectors (Dai et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022). In a study of Chinese cities, the application of industrial robots is shown to significantly reduce urban carbon emissions (Yu et al., 2023). At the overall level, the application of industrial robots can effectively enhance Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP). By replacing traditional inefficient labor and capital inputs and optimizing the resource allocation structure, industrial robots improve production efficiency and reduce the carbon emission intensity per unit of output. Specifically, as high-tech capital, robots are able to maintain a high degree of automation and precise control in the production process, thereby reducing energy consumption and waste. This efficiency improvement lowers the overall carbon intensity of industries and raises output efficiency, thus achieving a relative reduction in carbon emissions alongside economic growth and promoting the improvement of CTFP. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

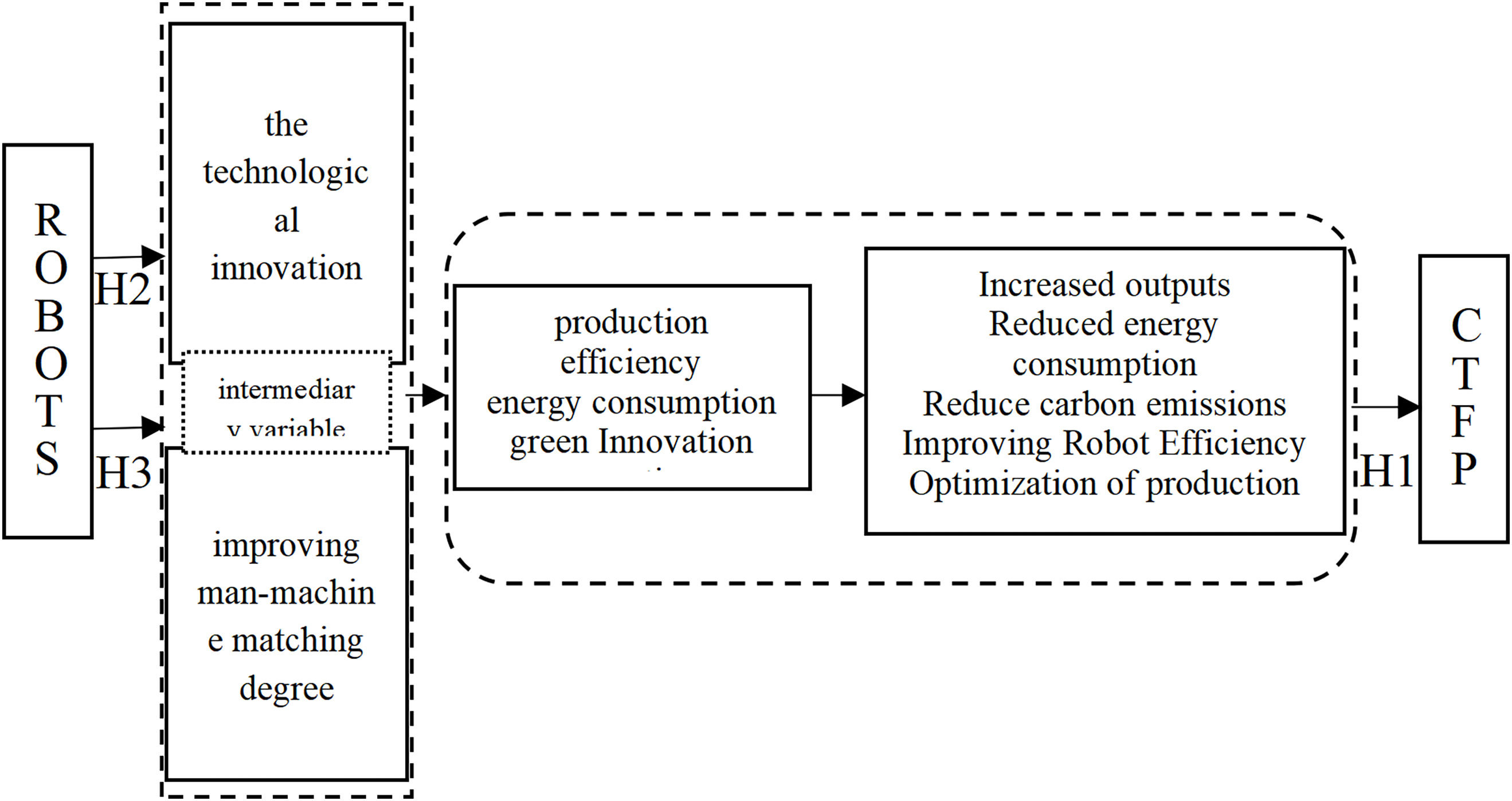

H1: The application of industrial robots can promote CTFP.

Industry 4.0 has accelerated the transformation of manufacturing toward intelligent production. Industrial robots, as advanced production technologies, play a central role by driving automation and enabling smart manufacturing systems (Enyoghasi & Badurdeen, 2021). Their widespread application generates technological spillovers that encourage firms to expand R&D investment and strengthen innovation activities (Liu et al., 2020). Empirical evidence shows that industrial robots significantly enhance firms’ innovation capacity (Luo & Qiao, 2023), promote green technological innovation, and improve productivity (Zhang et al., 2022). Improving technological innovation efficiency optimizes the allocation of innovation resources, strengthens industrial competitiveness, and enhances firms’ position in global value chains (Cheng et al., 2024). Moreover, technological progress not only improves productivity but also reduces energy consumption and pollutant emissions, thereby contributing to higher CTFP (Grossman & Kruger, 1995; Shao et al., 2016).Taken together, industrial robots influence CTFP primarily through technological innovation. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Technological innovation is an important mechanism for the influence of industrial robots in promoting CTFP.

Industrial robots are widely applied across industries, making human–machine collaboration a mainstream mode of production. Empirical studies indicate that the degree of human–machine matching is an important determinant of labor productivity (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Menshikov et al., 2020). Although artificial intelligence and robotics can enhance productivity, mismatches between humans and machines may lead to productivity losses, reflecting the so-called “productivity paradox” observed in certain contexts (Gordon, 2018; Hu et al., 2021). Specifically, only workers equipped with skills to collaborate efficiently with robots can fully realize the economic benefits of automation. From an environmental perspective, human–machine matching also affects carbon efficiency. Improvements in human–machine matching, together with a shift in labor structure toward higher-skilled workers, are shown to amplify the positive effects of AI applications on GTFP (Yang & Kuang, 2025). This suggests that better collaboration can reduce energy consumption, optimize resource allocation, and enhance overall productivity, thereby promoting improvements in carbon efficiency. Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Human–machine matching is an important mechanism for the influence of industrial robots in promoting CTFP improvement.

In summary, Fig. 1 depicts the underlying mechanism through which industrial robots enhance carbon total factor productivity (CTFP). Specifically, robots exert a direct effect (H1) by improving production efficiency, reducing energy consumption, and lowering carbon emissions. In addition, robots influence CTFP indirectly through intermediary channels (H2, H3), namely by fostering technological innovation and strengthening human–machine matching. These mediating mechanisms further stimulate green innovation and optimize resource allocation, thereby amplifying the contribution of robots to carbon total factor productivity (CTFP).

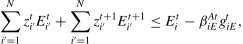

Description of research methods, variables, and dataResearch methodsTo test the impact of industrial robot applications on CTFP, the following model is constructed:

where CTFPitdenotes the level of CTFP of province i in year t; Robotsit denotes the application of industrial robots in province i in year t; μi denotes unobservable effects of individual; λt denotes effects of time; εit denotes a random error term; β0 is the intercept term; β1denotes the coefficient of industrial robots, and the magnitude indicates the degree to which industrial robots affect CTFP. Controlsit denotes a set of control variables.Variable selection and data sourcesExplained variablesCTFP is the explained variable. The data from 30 provinces (excluding Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao) in China from 2006 to 2019 are used to measure the changes in the carbon emission efficiency in each province. Current research on the efficiency of the low-carbon economy primarily focuses on carbon productivity and total factor productivity, with carbon productivity being a common current research topic. The most common method for calculating carbon productivity is to use the ratio of GDP to carbon dioxide emissions (Yin et al., 2024). This ratio is used to measure the economic output per unit of carbon emissions and is an important indicator for studying the balance between economic growth and the reduction of carbon emissions (Wu & Yao, 2022). However, there are drawbacks in using carbon productivity as an indicator for research; notably, it ignores some production variables in individual provinces, which leads to discrepancies between the research results and the facts. Thus, the more comprehensive CTFP is chosen for this study (Hu & Liu, 2016). There are different methods for calculating CTFP. Some scholars introduce carbon emissions into the analytical framework of total factor productivity for the calculation (Liu & Zhao, 2016), while others use capital, labor, and energy consumption as input variables, with GDP and carbon dioxide emissions as desired and non-desired outputs to calculate CTFP. The SBM (slack-based measure) directional distance function is used for calculation (Zhou et al., 2023), and the non-desired super-efficiency EBM model is employed for calculation (Ren & Sun, 2022). Each province is taken as a unit of analysis, with capital (K), labor (L), and energy (E) as input variables, GDP as the desired output variable (Y), and carbon dioxide emissions (C) as the non-desired output variable (Färe et al., 2007; Zhang, 2022). The environmental production technology (EPT) is thus defined as follows:

where EPT satisfies the basic production function principle. We also make three additional assumptions: weak disposability (where waste or undesirable outputs in the production process cannot be completely disposed of freely), zero-jointness (a special kind of relationship involving different outputs), and the assumption of a compact set (i.e., a bounded and closed set) (Färe & Grosskopf, 2005).To ensure accuracy in measuring CTFP, the EPT is calculated using the above methods for two consecutive periods, period t and period t + 1; the results are combined with the non-radial directional distance function (NDDF) as the BNDDF to calculate CTFP, relaxing the restriction that desired and undesired outputs must increase and decrease in equal proportions in the directional distance function (Zhou et al., 2012).Compared to earlier calculation methods, this method considers the lags of all factors, including input and output factors, and effectively solves the lack of feasibility in the assessment process. The CTFP estimated by this new method is thus more consistent with the theory of environmental economics. Following the above approach, we give the BNDDF formula as:

where the superscript A represents the biennial EPT, which combines all observations from periods t and t + 1 to form a production boundary. βiKAt,βiLAt,βiEAt,βiYAt,andβiCAt denote the total BNDDF and the intermediate BNDDF of all the factors for the i th province to be evaluated. The direction vector is set here g=(−gK,−gL,−gE,gy,−gC)for actual production, which indicates that we can improve the production performance of each province by reducing its inputs and bad outputs or by increasing the desirable outputs; ωk,ωl,ωe,ωy,andωC denote the weights of the factors, which sum up to 1. Three inputs are set, along with one desired output and one undesired output, with the weights set as (ωk,ωl,ωe,ωy,ωc)T=(19,19,19,13,13)T. Here, the above BNDDF is combined with the Luenberg index (LPI) to construct a new productivity indicator, the BLPI, to measure the change in CTFP in each province:When the BLPI value is greater than (less than or equal to) 0, it indicates that the CTFP of each province has improved (worsened or remained unchanged). K, L, E, Y, and C denote capital stock, labor force, energy consumption, real GDP, and carbon emissions, respectively, where capital stock is obtained with 2005 as the base period (Zhang et al., 2004), and the remaining data are acquired from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), provincial statistical yearbooks, and the Carbon Emission Accounts and Datasets (CEADS).

The core explanatory variableThe application of industrial robots (Robots) is the core explanatory variable. The number of industrial robot installations is adopted as the measurement indicator (Du et al., 2024). The calculation method draws on the number of industrial robots installed in various industries in China as reported by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), together with provincial employment data by subsector collected from the China Labor Statistical Yearbook (Kang & Lin, 2021; Lu & Zhu, 2021).The share of each industry in total national employment is then calculated and multiplied by the number of robots installed nationwide in each industry.

To ensure data consistency and the reliability of estimation, this paper selects the period from 2006 to 2019 as the sample interval. On the one hand, the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) has systematically published detailed industry-level robot installation data for China since 2006. The industry-level robot installation data from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) and the provincial-level employment data from the China Labor Statistical Yearbook are continuous and comparable, which facilitates the construction of provincial robot stock indicators. On the other hand, setting 2019 as the sample endpoint avoids short-term production disruptions and statistical anomalies caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing the estimation results to better reflect the long-term impact of robot adoption on Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP) under normal economic conditions. In addition, the period from 2006 to 2019 covers the critical stage of China’s accelerated development of automation and intelligent manufacturing, and the sample length is sufficient to meet the requirements of panel econometric modeling. The method of allocating robots to provinces is based on each province’s share of employment in different industries. This approach implicitly assumes that the distribution of robots across provinces is consistent with their employment structure, which may differ from the actual situation. However, due to the lack of IFR data at the provincial level, this method has not been adopted in the existing literature and thus remains a reasonable alternative, ensuring comparability with previous studies (Acemoglu &, Restrepo, 2020;Wang et al., 2025).

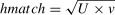

Mechanism variablesTwo mechanism variables are included. The first is technological innovation (Tech). R&D activities are the main source of technological innovation, which improves energy efficiency and the efficiency of raw material use during production. Tech is measured by the ratio of R&D expenditure to GDP in each province (Du & Lin, 2022). The second variable is human–machine matching (Hmatch), which reflects the productivity of industrial robots depending on workers’ proficiency in operating robots. Improvements in the efficiency of industrial robots affect carbon emissions, while human–machine matching is an important factor influencing robot efficiency. Coordination between robots and human capital is therefore used to calculate the human–machine matching:

where U=Robots×hum/(Robots+hum) and V=0.5×Robots+0.5×hum; hum is the level of urban human capital. Both industrial robots and human capital levels are normalized in the interval [0, 1] (Huang & Jiang, 2023).Instrumental variableThe instrumental variable approach is used to solve the endogeneity problem. The level of AI (i.e., the number of AI patent applications) is used as the instrumental variable. The level of AI is related to the development and application of robots but not to the error term of the model. When the differences in robot application to different regions are studied, the level of AI can be used to measure the acceptance and innovation of robot technology, thus better reflecting focus of this study. The data are retrieved from the State Intellectual Property Office according to the AI patent classification number in the Strategic Emerging Industries Classification and International Patent Classification Reference Relationship .

Other control variablesConsidering previous studies and the problem of omitted variables, several control variables at the inter-provincial and industry levels are included. All the data for the control variables described below come from the National Statistical Yearbook and the provincial statistical yearbooks.

(1) Urbanization (UL). The urbanization rate is measured as the proportion of the urban population relative to the total regional population (Bai et al., 2019).

(2) Infrastructure construction (Ic). Road infrastructure (Ic) is measured by the length of roads per square kilometer (Wang et al., 2015).For ease of comparison, the values are multiplied by 10,000 to reduce differences and better reflect the accessibility of road infrastructure.

(3) GDP per capita (Pgdp). Based on provincial population and GDP data (Ma et al., 2023), per capita output is calculated by dividing the region's GDP by its resident population. Changes in per capita GDP affect variations in Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP) (Kang et al., 2023).

(4) Industrialization (In). The level of industrialization is measured by the share of industrial value added in regional GDP, reflecting the degree of industrialization in the region’s economic structure (Luan et al., 2021).

(5) Education expenditure level (Pedu). This indicator is measured by the proportion of provincial education expenditure to provincial GDP, reflecting the intensity of investment in education.

(6) Labor force structure (Ls). This indicator is measured by the proportion of the total number of self-employed and individual entrepreneurs to the total number of employees in each province (Lee & Lee, 2022), reflecting the characteristics of the labor force composition.

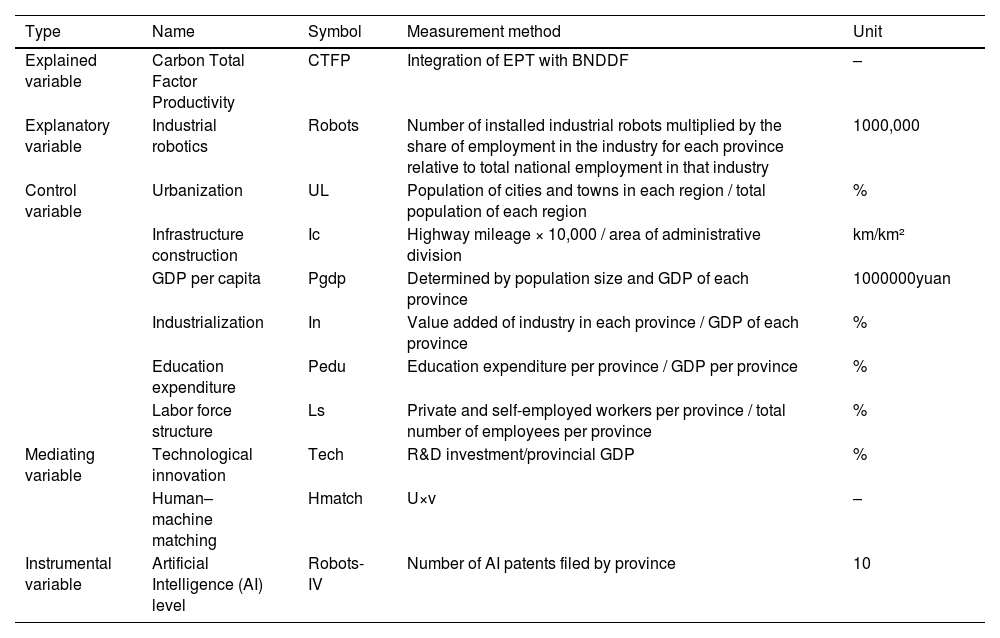

Table 1 summarizes the variable symbols and corresponding measurement methods used in this study. Specifically, Rbots denotes the density of industrial robots, measured by Number of industrial robots and workforce employment; CTFP represents carbon total factor productivity, calculated using the BNDDF combined with the Luenberg Index (LPI). Control variables are drawn from official statistical yearbooks. This framework ensures clarity and consistency in the empirical analysis.

Variable symbols and measurement methods.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. It can be seen that both the carbon total factor productivity (CTFP) and the number of industrial robots vary significantly across provinces, reflecting substantial disparities in economic strength and technological innovation capacity. Consequently, after the promotion of industrial robot adoption, the impact on CTFP is more pronounced in certain provinces, suggesting that implementation strategies should be tailored to local conditions in order to avoid resource misallocation. As shown in Table 2, CTFP includes negative values. This arises from the calculation process that integrates the BNDDF model with the EPT approach, under which CTFP is measured as a relative index. As a result, a small number of provinces appear with negative values in this framework. Such results do not imply that productivity itself is negative, but rather that, under the chosen reference frontier, the corresponding unit (or the sample as a whole) experienced a net productivity decline compared with the previous period. Specifically, since BNDDF is a non-radial model that allows inputs and outputs to adjust in different proportions, if the directional vector (EPT) is set relatively strictly or if outliers exist in the sample, the optimal combination of desirable and undesirable outputs for certain decision-making units may extend beyond the production possibility set, leading to negative estimates. This phenomenon simply indicates that a few units lie outside the feasible set in a given direction and does not materially affect the overall trend or empirical conclusions. The distributions of the remaining variables are generally consistent with those used in the existing literature.

Descriptive statistics.

Benchmark regression analysis is conducted according to Eq. (1). The gradual addition of control variables is used to study the impact of industrial robots on CTFP, and the results are shown in Table 3. From Columns (1) to (6) of Table 3, it shows that the coefficients of industrial robots are positive and significant at the 1 % level, which indicates that the application of industrial robots can have a positive impact on CTFP. Specifically, a one-unit increase in robot density is associated with a 14.7 % improvement in CTFP, suggesting that robot adoption yields substantial carbon-efficiency gains. Moreover, after control variables are added, the regression coefficient of industrial robots remains positive. The impact of industrial robot application on CTFP is primarily reflected in three ways, starting with improved productivity. Industrial robots can reduce the quantity of labor required for labor-intensive operations and improve the consistency of product quality through automation and smart technology. This means that more products can be produced with the same energy and material inputs. Improved productivity not only reduces energy consumption per unit of product but also reduces the scrap rate, thus reducing carbon emissions in general and improving CTFP.

Results of benchmark regressions.

In addition, industrial robots help to promote green manufacturing. The application of industrial robots in green manufacturing promotes clean production and resource recycling, accelerates industrial upgrading and transformation, improves the energy structure, reduces waste emissions and environmental pollution in the production process, improves the resource recycling rate to realize overall green transformation, and helps to improve CTFP.

Finally, industrial robots are linked to technological innovation. The introduction of advanced technologies, such as the Internet of Things, big data analysis, and smart energy management systems, is also conducive to the integration of industrial robots. Technological innovation not only helps to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions in the production process, but also helps firms to achieve more intelligent and efficient production management, which improves their own productivity and competitiveness. In realizing these economic benefits, firms can also reduce their impact on the environment, promote green and sustainable development, and further enhance the CTFP. All in all, industrial robots can significantly reduce carbon emissions while improving production efficiency, thus enhancing CTFP.

The above results indicate that the application of industrial robots has a significant and economically meaningful effect on Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP). This effect is not only statistically robust but also economically important, suggesting that industrial robots have become a crucial tool for simultaneously enhancing productivity and carbon efficiency. In terms of the functional form, within the observed range, the relationship between robot adoption and CTFP generally exhibits a strong linear pattern, although further analysis suggests the possibility of diminishing marginal returns. Specifically, during the initial stage of robot adoption, improvements in productivity and environmental performance are most pronounced, but as penetration increases, the marginal effect may gradually weaken. Therefore, to continuously realize the positive impact of robots on green productivity, it is necessary to complement their adoption with increased R&D investment, workforce training, and digital infrastructure development.

Although this study is based on provincial-level data from China, the findings reflect a general phenomenon during industrialization and industrial upgrading. When extrapolating these conclusions to other countries, institutional differences—such as energy structure, labor costs, and regulatory environments—must be carefully considered, as these factors can affect the marginal returns of robot adoption. Overall, the findings also have implications for economies outside China. In manufacturing-oriented countries, industrial robots can serve as an important lever for achieving high-quality, low-carbon growth, but their effectiveness depends on the implementation of context-specific policies and institutional arrangements.H1 is supported.

Robustness testTable 3 shows that the application of industrial robots can enhance CTFP. To test whether the conclusion is robust, four robustness tests are conducted. The first is to replace the core explanatory variable; the second is to regress the explanatory variable and control variables with a lag of one period; the third is to replace the regression model to solve the issue of between-group heteroskedasticity and within-group autocorrelation; and the fourth is to replace the regression samples (i.e., exclude municipalities directly under the central government). The level of economic development obviously varies from region to region in China, which may lead to a gap in the application industrial robots. Comparison between provinces and municipalities directly under the central government may not be valid because the latter have a unique position in the economy, politics, and other aspects. Therefore, the sample data of four municipalities—namely, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing—are deleted and regressed again.

Alternative explanatory variableThe wide application of AI can change today’s production methods and is an important part of smart innovation. Analysis is conducted from three perspectives—namely, intelligent inputs, production applications, and innovations and benefits (Sun & Hou, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). The entropy method is used to calculate the level of industrial intelligence (Int) in 30 provinces during the period 2011–2019. The level of industrial intelligence is then used to test the number of industrial robots. The test uses data from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistics Yearbook, and China High Technology Industry Statistics Yearbook.

As seen from the result in Column (1) of Table 4, after controlling for effects of province and year, industrial intelligence is significant at the 1 % level and positive. This proves that the promotion of industrial intelligence can also promote CTFP, which indicates that the benchmark regression results are robust.

Results of robustness test.

To further test the robustness of the baseline regression results, this study uses the number of robots per unit of industrial value added as an alternative variable for regression. This indicator can, to some extent, control for the influence of regional economic scale on robot usage and more accurately reflect the relative level of robot adoption. As shown in column (2) of Table 4, when robot density is scaled by industrial value added, the estimated coefficient remains positive, although it is significant only at the 10 % level. This indicates that, although the effect strength weakens under the alternative scaling approach, the results are generally consistent with the baseline findings, thereby supporting the robustness of the conclusions.

Regression with a lag of one periodAll explanatory and control variables are lagged by one period and then regressed again, while effects of province and year are controlled. Column (3) of Table 4 shows that the regression results remain significant, proving the robustness of the benchmark regression.

Alternative measurement modelThe GMM model is used for the regression. The result in Column (4) in Table 4 show that the significance level of industrial robots remained at 1 % and positively significant, which indicates that industrial robots still contribute to CTFP after substitution in the regression model, which is consistent with the conclusion obtained from Table 3.

Deletion of direct municipalities from the sampleThe regression result in Column (5) of Table 4 is from the sample after the deletion of the four municipalities of Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing. It shows that industrial robots still significantly enhance CTFP, which indicates that the benchmark regression results are robust.

Endogeneity issueDue to endogeneity issues, instrumental variable method and placebo test are used for testing.

Instrumental variable methodIn the previous benchmark regression, it is impossible to distinguish whether causality is unidirectional or bidirectional, so reverse causality could be a problem. Additionally, measurement errors may also lead to endogeneity problems. Measurement of industrial robot development level may be inaccurate, or the data may be incomplete, which could affect the accuracy of the regression results. For example, if the level of industrial robot development in a region is underestimated, the regression results may incorrectly assume that certain phenomena in that region are not affected by industrial robot development. Finally, omitted variable bias is a common endogeneity problem. In the benchmark regression, only a subset of factors that may affect industrial robot development are considered, while other possible factors are ignored. These omitted variables may be related to the variables under our consideration and could affect the regression results. Therefore, endogeneity due to omitted variables cannot be ignored. In some regions, a high level of industrial robotics development may attract specific types of industrial clusters, the formation of which may in turn contribute to the further development of industrial robotics in the region. This would then lead to a more pronounced increase in CTFP in the region. If the data on industrial robot inputs are omitted at the beginning of the sample statistics, and statistical errors are made due to opportunism at a later stage, some firms may overreport due to the implementation of the financial subsidy policy for intelligent transformation, or reported equipment that is not strictly industrial robots as industrial robots, which may also lead to biased regression results (Sun & Hou, 2021). Therefore, artificial intelligence (AI) is used as an instrumental variable to address potential endogeneity issues. AI is measured by the number of AI patent applications, with data sourced from the China National Intellectual Property Administration. Although few studies have currently used AI as an instrumental variable, AI is employed to tackle endogeneity (Bai et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2022).First, regarding the relevance condition, AI technology and industrial robots exhibit a high degree of technological complementarity. Advances in AI algorithms such as computer vision, speech recognition, and machine learning significantly enhance the perception and control capabilities of robots, thereby promoting their widespread application in manufacturing. This close technological link ensures a significant correlation between regional AI development and robot adoption.Second, regarding the exogeneity condition, regional AI levels do not directly affect CTFP, whose determinants mainly include production technology, energy efficiency, and carbon emission structure. The effect of AI on CTFP occurs only through the mediating pathway of promoting robot adoption. Moreover, AI development is primarily driven by global technological progress and national innovation policies rather than productivity shocks in specific regions, which reduces the likelihood that unobserved regional factors simultaneously affect both AI and CTFP. Therefore, AI as an instrumental variable can effectively mitigate endogeneity issues arising from reverse causality, measurement errors, and omitted variables, ensuring a more robust identification of the causal effect of robot adoption on CTFP. To test for reverse causality, we conducted a Granger causality test (Table 6): based on a one-period lag, the p-value fails to reject the null hypothesis that “CTFP does not Granger-cause AI,” supporting the notion that AI shocks are not driven by prior productivity.

Table 5 shows that in the first-stage regression of industrial robots using the instrumental variable, the instrument satisfies the relevance condition: the first-stage coefficient is positive and highly significant (Table 5), with a Cragg–Donald/Wald F statistic of 750.38, ruling out concerns about weak instruments. This sufficiently demonstrates a significant correlation between the instrument and robot adoption, meeting the relevance requirement. The Anderson LM test is significant at the 1 % level, rejecting under-identification.In the second-stage regression results, column (2) shows that the coefficient of robot adoption is positive and significant at the 1 % level. Since there is only one instrumental variable in this study, an over-identification test cannot be conducted. The exogeneity of the instrument is primarily supported by theoretical reasoning. On the one hand, the level of AI development is closely linked to industrial robot adoption, as robots represent the most typical application of AI technology in manufacturing, thus satisfying the relevance condition. On the other hand, AI development is mainly driven by algorithmic breakthroughs, research investment, and information and communication infrastructure, which have no direct relationship with regional CTFP; its impact on CTFP occurs only through the channel of robot adoption.After using the instrumental variable, the regression results remain significant. Therefore, it can be concluded that the chosen instrument is valid.

Endogeneity tests: instrumental variables.

The conclusion obtained from the benchmark regression in Table 3 is that industrial robot applications can increase CTFP. This conclusion may be due to the omission of certain considerations. Despite the inclusion of some control variables, it is not possible to avoid such omission completely; in the regression, we controll for province and time, but there may be additional characteristics that could not be observed. It is thus possible that an unknown factor influences both industrial robot application and CTFP, causing them to show the regression results in Table 3, rather than those results simply being the effect of industrial robot application on CTFP. This is a typical endogeneity problem.

A counterfactual placebo test is therefore constructed (Huang et al., 2024) to rule out the possible effects mentioned above. Based on the available data, the number of industrial robots is randomly assigned to each province, and a regression is conducted to observe the coefficients of the explanatory variables. The pseudo-treatment group is randomly generated. Therefore, if this conclusion holds, then the number of industrial robots would not have a significant effect on CTFP, and the regression coefficients for the placebo treatment variables would not significantly deviate from zero. Conversely, if the coefficients for Robots significantly deviate from zero, it implies an identification bias in the model. Fig. 2 demonstrates the estimated kernel density distribution of the coefficients of Robots (the number of industrial robots) after 1000 bootstrap resamples. As shown, the coefficients obtained from the pseudo-treatment group generated randomly are centered around zero and exhibit no significant deviation, indicating that the observed positive effect of Robots in the actual sample is unlikely to arise from random chance. This supports the robustness of our main results and reduces concerns about spurious correlations. The benchmark regression results obtained in Table 3 are also consistent with the placebo test, which suggests that our estimation results are not seriously biased and that the conclusion that the application of industrial robots enhances CTFP is robust.

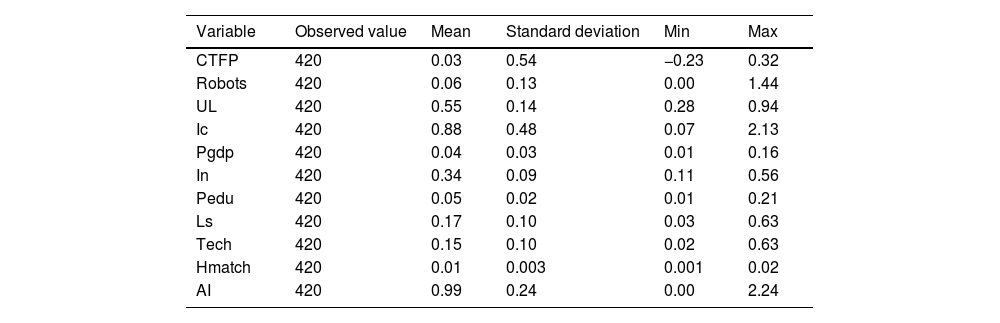

Heterogeneity analysisFactor heterogeneityIndustry can be classified into labor-, capital-, and technology-intensive types (Yang et al., 2018). Labor-intensive industries include clothing and textile, wood products, other manufacturing, metal, and non-metal; capital-intensive industries include food and beverage, paper and printing, chemicals, plastics, and metal smelting; and technology-intensive industries include electronic and electrical, general, and automotive manufacturing.

The regression results in Table 7 show that the coefficients for technology-intensive, capital-intensive, and labor-intensive industries are all positive and significant at the 1 % level, indicating that industrial robots can enhance Carbon Total Factor Productivity (CTFP) across different types of industries. As shown in Table 8 recommendations for Inter-Group Difference Coefficients, the effect of industrial robots is most pronounced in labor-intensive industries. Further inter-group difference tests confirm this conclusion: the overall difference is significant (p = 0.000), indicating systematic differences among the three types of industries. Specifically, the difference between technology-intensive and capital-intensive industries is not significant (p = 0.141), whereas the differences between technology-intensive and labor-intensive (p = 0.004) and between capital-intensive and labor-intensive (p = 0.000) industries are highly significant. This suggests that labor-intensive industries exhibit the strongest marginal effects of robot adoption, while technology-intensive and capital-intensive industries perform more similarly.

Heterogeneity analysis: factor heterogeneity.

From an economic perspective, these industry differences can be explained by variations in marginal effects and initial automation levels. In labor-intensive industries, robots can replace large amounts of labor, reduce employment costs, and continuously perform complex production tasks, leading to substantial improvements in productivity and carbon efficiency. This implies that the marginal effect of robots is largest during the initial stage of adoption. However, as robot penetration increases, the incremental benefits may exhibit diminishing returns, and without complementary investments in technological innovation, workforce retraining, and digital infrastructure, the marginal effect will gradually weaken. In contrast, capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries already possess relatively high levels of automation and advanced production systems. In these industries, the marginal contribution of additional robots to CTFP is relatively small, with the relationship approximating a low-slope linear trend. Moreover, in highly technological industries, improving energy efficiency and adopting clean energy have become the core pathways for enhancing CTFP, which limits the relative role of industrial robots. Nonetheless, robots still provide value in these industries, for example, by optimizing resource allocation, improving process precision, and complementing other technological advancements.

Technical complexity heterogeneityAccording to the technology intensity classification guided by policy, industries are grouped by technological complexity to reveal the heterogeneity of robots’ impact on green productivity (CTFP) across different sectors. In high-technology industries, robots primarily enhance production efficiency and carbon reduction through technological innovation and process optimization; in low-technology industries, they contribute mainly through labor substitution and efficiency improvements. Such classification not only facilitates heterogeneity regressions and robustness checks but also provides valuable references for enterprises and governments to formulate differentiated policies on intelligent manufacturing and green development. The classification follows official documents such as the Catalogue of China’s High-Tech Industries and Made in China 2025. High-technology industries—including electronics and electrical equipment, automobile manufacturing, and chemicals—are characterized by high R&D intensity, advanced production processes, and significant innovation demand. Medium-technology industries—such as plastics, metals, metal smelting, and non-metals—exhibit moderate technological complexity and precision requirements. Low-technology industries—including food and beverages, textiles and apparel, wood products, paper and printing, other miscellaneous, and general manufacturing—are marked by labor-intensive and resource-intensive production with relatively low innovation intensity.

Table 9 presents the effects of industrial robots on CTFP across industries with different technological levels. The results show that the robot coefficients are significantly positive in high-, medium-, and low-technology industries, but the magnitudes differ markedly: the coefficient is only 0.019 in high-technology industries, rises to 0.101 in medium-technology industries, and reaches as high as 0.307 in low-technology industries. This indicates that as the technological level of industries decreases, the contribution of robot adoption to CTFP becomes increasingly pronounced. From an economic perspective, this difference is reasonable. High-technology industries already possess high levels of automation and relatively mature green production systems, so the marginal effects of additional robots are limited. In contrast, medium-technology industries, with moderate levels of automation and production models, can benefit more from robot adoption in terms of efficiency gains and carbon reduction. Low-technology industries rely heavily on labor-intensive production, where substitution effects are strongest, leading to the most significant improvements in CTFP. Notably, although robots yield the largest marginal effects in low-technology industries, their marginal returns may decline as penetration deepens, making innovation investment and workforce retraining essential for maintaining sustainability. Further analysis of between-group differences in Table 10 confirmed these findings: the overall difference is highly significant (p = 0.002), indicating systematic variation among the three industry groups. Specifically, differences between high- and medium-technology industries are significant (p = 0.018), between high- and low-technology industries extremely significant (p = 0.000), and between medium- and low-technology industries also extremely significant (p = 0.000). These results provide further evidence that the marginal contributions of robot adoption are substantially greater in medium- and low-technology industries than in high-technology industries. This finding is not only relevant to China but also offers insights in an international context. For developing economies, where industrial structures are often dominated by low- and medium-technology industries, industrial robots hold considerable potential for improving productivity and driving green transformation. In developed economies, where high-technology industries account for a larger share, robot adoption is more about deep integration with digital and green technologies, thereby delivering sustained and incremental efficiency improvements. Therefore, when promoting robot adoption, countries should tailor policy packages to their industrial structures and technological development levels in order to maximize the impact of robots on CTFP.

Technical Complexity heterogeneity.

From an international perspective, in emerging economies where labor-intensive manufacturing remains dominant, the potential gains from robot adoption are particularly significant, though attention must be paid to labor market transitions and social protection issues. In developed economies, the role of robots is more focused on consolidating existing digital and green technology achievements, promoting incremental productivity improvements, and ensuring deep integration with innovation ecosystems. Therefore, while different countries may exhibit variation in effect size and marginal returns, overall, industrial robots play a broadly applicable role in enhancing carbon total factor productivity, offering valuable insights for economies at different stages of industrialization in their pursuit of green transformation and high-quality development.

Level of market developmentMarket development exerts an important impact on the application of industrial robots. It can influence the performance, demand, and promotion of industrial robots based on the market demand, supply, and environment. As the index ordering changes in different years in each region are small, the 2019 marketization index is taken as a reference and the sample is divided into two categories: high market development and low market development. The marketization index is obtained from the China sub-provincial marketization index database.

The regression results in Table 11 show that in high-marketization provinces, the coefficient of Robots is 0.155 (significant at the 1 % level), while in low-marketization provinces it is 0.311 (significant at the 5 % level). Although the group difference test result of p = 0.263 indicates that the two coefficients are not statistically different, these estimates are still of important reference value from an economic perspective. Specifically, a one-unit increase in robot density leads to about a 15.5 % and 31.1 % improvement in CTFP, respectively, and such effect magnitudes are of practical significance for promoting green transformation and improving carbon reduction efficiency. Overall, industrial robots significantly promote CTFP regardless of the level of marketization, but the strength of the effect is influenced by factors such as institutional environment, supply chain development, and resource allocation efficiency.

Heterogeneity analysis: market development and government support.

This finding not only reveals the heterogeneous effects of robot application under different marketization environments in China, but also provides valuable reference for other countries. For developing economies, emphasis should be placed on improving infrastructure, strengthening supply chains, and enhancing labor skills, so as to avoid low robot utilization rates and inefficiencies in resource allocation caused by institutional and environmental deficiencies. For developed economies, attention should be paid to the possible diminishing marginal effects, avoiding reliance solely on the expansion of robot numbers, and instead promoting the integration of intelligent systems, data analytics, and green technologies, so as to achieve the dual goals of productivity growth and carbon reduction.

Policy supportProvincial government work reports are collected to measure local government policy support for AI by examining whether these reports include the topic of AI (Yao et al., 2024). To highlight the characteristics of interest, we also add whether the topic of industrial robots is included in the government work reports as an auxiliary measurement tool. Because AI is only written into the government work report since 2017, the reference value of 2017 is not significant. To ensure accuracy, only reports for 2018 and 2019 are examined. The regions are then divided into those with strong government support and those with weak government support.

The regression results in Table 11 show that in provinces with stronger government support, the coefficient of Robots is 0.195 (significant at the 1 % level), while in provinces with weaker government support it is only 0.013 (insignificant). This indicates that the policy environment plays a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of robot application. From an economic perspective, under strong support, a one-unit increase in robot density can lead to about a 19.5 % improvement in CTFP. This marginal effect is far greater than that under weak support, suggesting that policy incentives substantially enhance the productivity and emission reduction effects of robot application. Specifically, fiscal subsidies, tax reductions, and R&D investment not only lower the initial costs for firms to adopt robots, but also accelerate technological progress and the diffusion of applications, thereby amplifying the role of robots in green production. At the same time, strict environmental regulations and well-developed digital infrastructure (such as 5G and industrial internet) provide institutional and technological guarantees for robot application, enabling robots to improve productivity while effectively reducing carbon emissions.

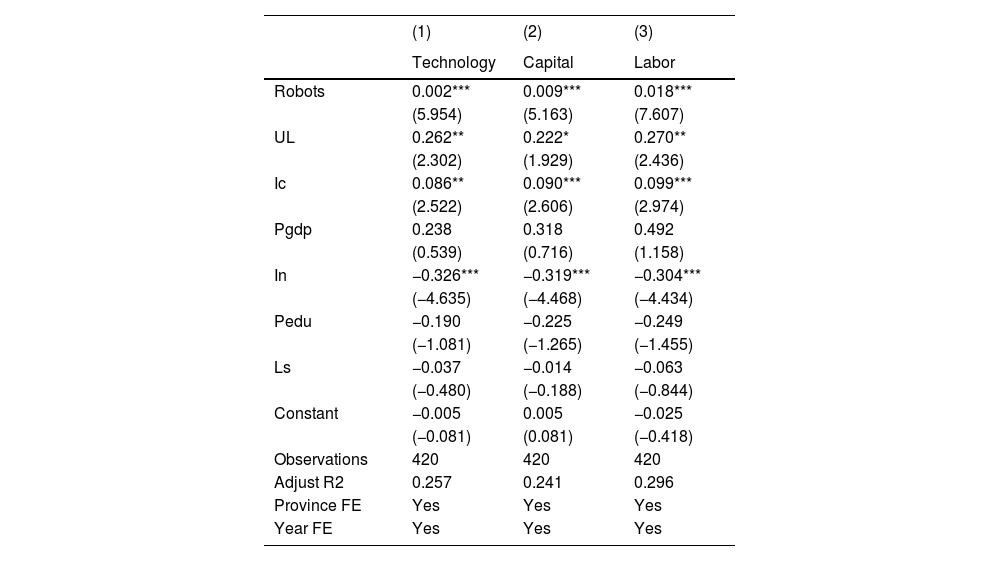

Mechanism testingThe above benchmark regression and robustness test show that the application of industrial robots has a significant effect on inter-provincial CTFP, and the effect is robust. In the mechanism analysis section, we further explore how industrial robot application affects CTFP in each province and analyze its internal mechanism of action. A mediating effect model is constructed to test the mechanism (Jiang, 2023):

where Mit is the mechanism variable, representing the technological innovation and human–machine matching in province i in year t. The other variables have the same meaning as in the benchmark regression. Eq. (7) is used to test whether the mechanism variable is a channel through which industrial robots affect CTFP. The main concern here is the coefficient of the mechanism variable; if the coefficient is positive, industrial robots can effectively increase CTFP through the mechanism variable, and vice versa. Robots play an important role in solving repetitive, high-risk, and precision-operational tasks, facilitating the development of automation technology, collaborative robotics, and human–machine interaction technology and driving technological innovation to meet the challenges posed by transformational changes in manufacturing. Industrial robots promote green technology innovation by increasing production profitability and reducing labor costs (Long et al., 2024), and technological innovation plays a crucial role in enhancing CTFP. Advances in green technology are found to be the basis for reducing production costs and increasing total factor productivity (Song et al., 2022). Technological innovation can reduce energy consumption by introducing more efficient production equipment and technology. This can lead to the gradual replacement of traditional highly energy-intensive and polluting production methods with cleaner, low-carbon processes in a way that directly reduces carbon emissions and increases CTFP. Influenced by the development of AI and automation technology, human–machine matching is increasingly important in modern production. The accelerated progress of smart technologies has unleashed a huge green development potential, which is conducive to enhancing green total factor productivity. Smart technologies are providing a key breakthrough in the new round of scientific and technological revolutions and a new opportunity for the future transformation of industries. Through human–machine collaboration, firms can better realize flexible manufacturing and customized production, while reducing overproduction and waste. This on-demand production mode helps to reduce resource consumption and carbon emissions and improve CTFP.Technological innovationIn Column (1) of Table 12, the estimated coefficient of technological innovation is significantly positive, which indicates that technological innovation is an important mechanism for the influence of industrial robots on CTFP. Technological progress is a powerful guarantee of combined economic growth and environmental development (Wang et al., 2023). Technological innovation is shown to significantly improve production efficiency and resource use (Liu et al., 2024). Firms can obtain greater profits through innovation, which motivates them to increase R&D efforts. Improving technological innovation can also promote infrastructure construction and the promotion of related technologies, which can help firms to optimize the allocation of resources, improve energy efficiency, and reduce carbon emissions.

Results of mechanism analysis.

In Column (2) of Table 12, the estimated coefficient of human–robot matching is still significantly positive, which indicates that human–robot matching can strengthen the effect of industrial robots on CTFP. When human–robot matching is low, the collaboration between industrial robots and laborers is insufficient, which results in productivity loss (i.e., the Solow paradox), which restricts industrial robots from exerting their carbon emission reduction effect (Huang & Jiang, 2023). Only with a high level of matching can industrial robots be more skillfully applied to various industries and strengthen their inhibiting effect on carbon emissions. Reasonable human–robot matching better enables robots and human workers to work together. Robots are good at tasks that are highly repetitive and require high precision, while humans are good at tasks that are highly flexible and require judgment. The combination of the automation capabilities of industrial robots and the experience of human workers can effectively reduce waiting time and equipment idleness, while ensuring the continuity and stability of the production process. This reduces resource waste and energy consumption while increasing CTFP. In summary, as technological innovation and human–machine matching improve, the effect of industrial robots on CTFP is further strengthened, so H2 and H3 are supported.

Conclusions and policy recommendationsResearch conclusionEnhancing carbon total factor productivity (CTFP) is a necessary step toward achieving high-quality development. The application of industrial robots not only exerts a profound influence on economic and social development but also brings fundamental changes to environmental governance. Accordingly, the impact of industrial robots on CTFP has become an important research topic. Based on panel data from 30 Chinese provinces and municipalities during 2006–2019, this study investigates the effect of industrial robots on CTFP. Employing a two-way fixed effects model and a series of robustness checks, we find that industrial robot adoption significantly improves CTFP, and the results remain consistent across specifications. Mechanism analysis further reveals that robots enhance CTFP primarily by fostering technological innovation and optimizing human–machine matching. Heterogeneity analysis shows that the positive effects of robot application are more pronounced in labor-intensive industries, low-technology sectors, and regions with stronger policy support.

These findings offer several policy implications for China. First, expanding the use of industrial robots should be accompanied by greater investment in R&D and innovation ecosystems to strengthen technological spillovers. Second, targeted workforce training and retraining programs are needed to enhance human–machine complementarity and mitigate potential risks of labor substitution. Third, institutional and policy support—including market-oriented reforms and incentive-compatible environmental policies—is critical for maximizing the contribution of robots to green productivity growth.

Importantly, both emerging and advanced economies face the dual challenge of industrial upgrading and environmental sustainability. When combined with supportive institutional arrangements, industrial robots can simultaneously boost productivity and reduce carbon intensity. For economies with similar industrial structures, fostering innovation capacity, improving workforce adaptability, and strengthening market mechanisms are key to unlocking the sustainable potential of robotics. Therefore, industrial robots should not merely be regarded as tools for efficiency gains but as strategic instruments for achieving global high-quality and low-carbon growth.

Limitations and future avenues for researchThe study has the following limitations: First, the data only covers provincial-level data from 30 provinces between 2006 and 2019, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Second, the assumption of robot distribution based on provincial employment structure may deviate from the actual situation. Third, the study does not account for the moderating effects of external factors, such as technological progress and policy changes, on the impact of robot adoption. Finally, although the BNDDF method is used to calculate CTFP, there are still limitations in handling extreme data. Future research could further explore more refined models with multidimensional variables and extend the analysis to other countries or regions to examine whether the findings hold in different institutional and economic contexts.

Policy recommendationsBased on the above analysis, several policy recommendations can be proposed. First, the adoption of industrial robots should be actively promoted, expanding both the breadth and depth of their application. Governments are encouraged to increase R&D investment, establish robotics innovation hubs, and develop information-sharing platforms to facilitate market demand and technological exchange. Financial instruments such as tax incentives, subsidies, and low-interest loans can be employed to reduce corporate costs—especially for small and medium-sized enterprises—thereby encouraging the adoption of robotics technology to enhance productivity, lower emissions, and ultimately improve labor cost efficiency.

Second, strengthening technological innovation and human–machine matching is crucial, as these are the two main channels through which robots enhance CTFP. Public funding can support the development of robotics and human–machine interaction technologies to improve usability and adaptability. Simultaneously, vocational training and employment services should be reinforced to help workers affected by automation acquire new skills. Firms should be encouraged to adopt advanced human–machine interaction systems to improve competitiveness and operational efficiency.

Third, local governments are advised to integrate robotics development into regional strategies, providing targeted support for smart factories and establishing demonstration centers and data platforms to validate application outcomes. However, potential risks—such as labor displacement, regional disparities, high initial costs, and cybersecurity threats—must be carefully managed. Policymakers should seek a balance between productivity gains and social-economic safeguards when promoting systematic robot adoption.

CRediT authorship contribution statementYu Ma: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yongqi Ma: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. Zijun Ding: Validation, Supervision, Software.

Yu Ma,Professor, Doctor of Economics, Research Center of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Kashi University, Shandong Technology and Business University,Research direction: Macroeconomics and International Finance, ZIP code: 264005, Email: my555 @163.com, Mobile phone: 18053561391.