This study investigates the complex, nonlinear dynamics of the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within national innovation ecosystems (NIEs), addressing a critical gap in understanding SDG saturation. Studying this topic is crucial because, despite the growing importance of sustainability issues in innovation ecosystem research driven by social and economic pressure, the literature remains fragmented and undecided, lacking a clear understanding of complex governance and operational frameworks in NIEs. Employing the Bass diffusion model, we analyze 22 years of SDG Index score data (2000–2021) from 177 countries/regions. The model quantifies SDG saturation time, accounting for complex interdependencies and threshold effects overlooked by traditional linear models. Findings reveal characteristic S-shaped adoption curves for most countries, indicating initial slow progress, acceleration driven by imitation, and eventual saturation. Geographical and socioeconomic clustering analyses highlight distinct patterns in SDG progress that depend on the peculiarities of complex systems in national contexts. High-income countries exhibit greater innovation efforts but lower saturation potential due to the proximity to SDG ceilings, while lower-income countries face complex structural constraints. The Bass model proves effective for forecasting SDG saturation and informing policy interventions in complex systems like NIEs, emphasizing the need for context-dependent governance and resource allocation to accelerate equitable sustainable development across the globe.

National innovation ecosystems (NIEs) can accelerate technological, social, and economic progress toward achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by fostering collaboration, innovation, and entrepreneurship (Azmat et al., 2023; Brás & Robaina, 2024; Iizuka & Hane, 2021; Liao et al., 2024; Liu & Stephens, 2019; Nylund et al., 2021). Specifically, a study on 131 countries demonstrates that NIEs improve the achievement of SDGs (Wei et al., 2025) through the development of eco-innovations and green technologies (Abdullai et al., 2022; Fatma & Haleem, 2023; Yikun et al., 2022) entrenched with the tackling of societal issues and grand challenges (Ritala, 2024).

Nevertheless, their effectiveness in regard to SDGs can be constrained by various barriers as well as complexity issues, including contingent approaches in innovation-as-a-context ecosystems, institutional inertia, resource (absorption) limitations, and inadequate and nonlinearly intertwined efforts among the multiple agents in NIEs (Gifford et al., 2020; Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2024; Ponsiglione et al., 2021; Ponta et al., 2023; Qiao et al., 2024). For instance, high-income nations show 2.3 times greater SDG progress per dollar invested in innovation activities than low-income countries, due to better institutional frameworks that mitigate the complexity of NIEs (Prokop et al., 2021). This trend is confirmed by the overall dominance of the agenda for implementing circular ecosystems in the Global North (Aryee et al., 2025). The same research shows that southern/emerging countries are underexplored and necessity-driven contexts for circular innovation ecosystems, as well as being more chaotic in their implementation. In fact, the main differences concern emergence, orchestration, and governance dynamics. Telling examples relate to such sectors as: organic food in Brazil (Ferrari et al., 2023), textiles and apparel in Romania (Staicu & Pop, 2018), biochemical energy in India (Mukherjee et al., 2021), agriculture in China (Zhong et al., 2012), construction, and waste (Gyimah et al., 2024). Another research shows that NIEs in complex contexts, such as developing economies (e.g., Brazil, Pakistan), increase productivity in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) by 22–40 % and reduce resource waste by 15 % (Jan et al., 2025). On the other hand, the complexity of post-conflict Ukraine's ecosystem requires enhanced academic–business links to accelerate postwar SDG alignment (Kuzior et al., 2022).

Globally, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has shown that insufficient emphasis on sustainability-oriented innovation is linked to worsening performance in the achievement of SDGs (WEF, 2025a), whilst NIEs drive sustainability most effectively when integrating inclusive and more structured governance involving multiple agents in complex systems (Wei et al., 2025). Indeed, over the past decade, research on innovation ecosystems has focused primarily on understanding their structure, dynamics, and impact on economic growth (Ancona et al., 2023; Marinelli et al., 2023; Rabelo Neto et al., 2024; World Economic Forum, 2020; see also Spigel, 2017; Van de Ven, 1993) by adopting the lenses of complexity theory to investigate the set of actors, activities, and relations that determine the performance of ecosystems (Chatti et al., 2024; Granstrand & Holgersson, 2020; Isenberg, 2016; Russell & Smorodinskaya, 2018; Toth et al., 2024). Moreover, several definitory efforts have been undertaken in order to identify the differentiating elements of innovation ecosystems, such as actors’ heterogeneity, actors’ interdependence, and system-level outcomes, all of them calling for a specific focus on complexity issues. In fact, innovation ecosystems are shaped by coevolutionary microfoundations, whereas complex, nonlinear feedback loops among actors (e.g., firms, institutions) create emergent outcomes (Breslin et al., 2021) and varied system-level outcomes depending on the ecosystem typology—i.e., innovation ecosystem, business ecosystem, platform and technology ecosystems, entrepreneurial ecosystem, or knowledge and open innovation ecosystems. Similarly, Reed et al. (2025) criticize linear “innovation pipeline” models, advocating instead approaches that consider the impact of policy shocks and adaptive strategies in triggering cascading transformations across ecosystems. Zhang et al. (2023, 2024) prove that green innovation spreads through unequal connection nodes in complex networks, arising nonlinearly from actors’ micro-interactions (e.g., firms, universities, policymakers) (Zhou & Li, 2024). Such interactions may include different agents’ activities, such as pollution taxes or default costs altering opportunity costs, thus incentivizing green cooperation in NIEs, policy shifts, or startup disruptions. Moreover, they may trigger disproportionate impacts across the ecosystem (Zhang et al., 2024), learning and co-evolution dynamics among actors (firms, governments, universities) that create emergent behaviors challenging linear predictions (Miller et al., 2024) or self-organization properties to organically reconfigure around shared goals, driven by the growing emphasis on the sustainability transition in policy and business strategies (Han et al., 2019; Toth & Hary, 2024).

In fact, scholars have recently explored convergent topics related to innovation ecosystems and sustainability issues by emphasizing the importance of integrating sustainability and social issues into innovation practices, and reflecting the need for adaptive strategies when dealing with the complexity of innovative organizations and ecosystems (Pham & Vu, 2022; Pilelienė & Jucevičius, 2023; Ritala, 2024; Zeng et al., 2017). Sustainability issues are gaining momentum in innovation ecosystem research (Liu & Stephens, 2019; Ritala, 2024) due to the increasing recognition of environmental and social impacts stemming from cooperative innovation efforts (Nylund et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2020), the need for collaborative and cross-sectoral approaches—e.g., industrial symbiosis (Liu et al., 2024)—evolving policies and market demands in complex regulatory frameworks (Agasty et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), and the importance of integrating sustainability into business models and regional development (Bakry et al., 2022; Oskam et al., 2020; Peñarroya-Farell et al., 2023). From the managerial and policy perspectives, sustainable innovation ecosystems impact the achievement of the goals set in the UN Agenda 2030 (United Nations, 2015) through collaboration among diverse stakeholders (Nylund et al., 2021), digital transformation and integration of emerging technologies (Dionisio et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2024; Springer et al., 2025), and supportive policies (Dmytrenko & Kuba, 2024), though their effectiveness can be hindered by barriers such as a lack of resources, networking, and institutional support (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024).

However, despite the growing number of publications on (sustainable) innovation ecosystems, field literature remains fragmented and lacks an understanding of the governance and operational frameworks of innovation ecosystems (Xu & Li, 2024), particularly in the context of sustainable development (Pilelienė & Jucevičius, 2023). Moreover, a systematization of the theoretical framework related to the complex, adaptive, nonlinear interactions occurring among actors in innovation ecosystems, as well as of their social, environmental, and economic sustainability dimensions, is still missing (Breslin et al., 2021; Ponsiglione et al., 2021; Ponta et al., 2023; Reed et al., 2025; Thomas et al., 2025). In addition, a strain of recent scientific literature highlighted the dark side of the relationship between innovation and innovation ecosystems, and SDGs, emphasizing how the former can have a negative impact on the achievement of sustainability goals (Berry et al., 2024; Islam, 2025; Yuan et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). This pairs with the undecided discourse in the literature about whether the complexity of regulatory and cooperation frameworks in NIEs affects—positively or negatively—the capability of countries to achieve the SDGs, given the contrasting findings regarding high-income vs low-income countries, and developing vs war-torn/reconstruction economies (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024; Jan et al., 2025; Kuzior et al., 2022; Prokop et al., 2021).

Hence, existing studies concur that NIEs enable sustainability via collaboration (e.g., Nylund et al., 2021) but disagree on context-dependent and governance pathways (Pilelienė & Jucevičius, 2023; Xu & Li, 2024), which are influenced by nonlinear interactions among agents in complex systems (; Ponsiglione et al., 2021; Ponta et al., 2023; Thomas et al., 2025) and affected by the undecided role of ecosystem complementarities concurring with system-level value creation (Baldwin, 2024; Samuelson, 1974; Teece, 2018).

Finally, three critical research gaps emerge from these premises. First, there remains a significant lack of understanding about the comprehensive effects of complex governance models and actor dynamics on countries’ achievement of SDGs in NIEs (Reed et al., 2025). Second, while studies increasingly recognize the impacts of innovation ecosystems on SDGs (e.g., through technological externalities or governance issues), there is insufficient empirical research on the extent, speed, and variability of those effects across different national contexts (Berry et al., 2024; Islam, 2025). Third, from the methodological perspective, quantitative studies are underutilized in the field of innovation ecosystems overall (Aryee et al., 2025). Moreover, most of the literature is skewed towards qualitative efforts like conceptual works or literature reviews (Pietrulla, 2022; Trevisan et al., 2022), thereby missing the potential complementary findings from statistical testing or hitherto unexplored applications of data-driven prediction efforts that our work aims to cover, at least partially (Aryee et al., 2025).

Hence, our research questions are: (1) Do national innovation ecosystems play a role in the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals in the 193 UN member countries, and if so, how?; and (2) What are the cross-country differences in terms of expected SDG saturation levels over time?

As such, this study aims to investigate the overall impact of sustainable innovation ecosystems on the achievement of country-level SDGs over time, from 2000 to 2021. More specifically, we aim to predict when each country will achieve saturation level (100 %), indicating when it is expected to achieve a satisfactory proportion of its SDG fulfillment potential.

The relevance of this prediction is fourfold. First, it helps in understanding governance and policy integration, as sustainable innovation ecosystems align national policies with local actions through stakeholder interactions, e.g., governments and communities. Examples include the EU Green Deal’s regional hubs (European Commission, 2023), Rwanda’s decentralized energy systems supporting SDG 7 (UNDP, 2024), and Sweden’s national ecosystem strategy for SDGs (Sachs et al., 2024), though measuring effectiveness remains challenging. Second, these ecosystems drive economic and technological progress impacting SDGs via the twin transition, such as Sweden’s textile recycling reducing waste (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2023) and green tech leapfrogging in developing nations (World Bank, 2024). They contribute to SDGs 7–9 and 12 (UNEP, 2024) by creating resilient industries and boosting digital inclusion, as seen in Uganda’s gender-inclusive tech hubs (ITU, 2023). Third, they promote social inclusion, e.g., Montreal’s healthcare collaborations advancing SDG 3 (Larsson et al., 2024) and Chile’s IoT water management empowering marginalized groups, but disparities and gender discrimination persist, calling for more equitable resource models and studies (African Development Bank, 2025; UN Women, 2024). Fourth, these ecosystems enhance resilience against challenges like Denmark’s wind energy for climate action (IEA, 2023) and South Korea’s digital health platforms during the pandemic (WHO, 2024), though systemic impact metrics need development (SDSN, 2024). More research is necessary to scale successful models across nations (World Economic Forum, 2025b).

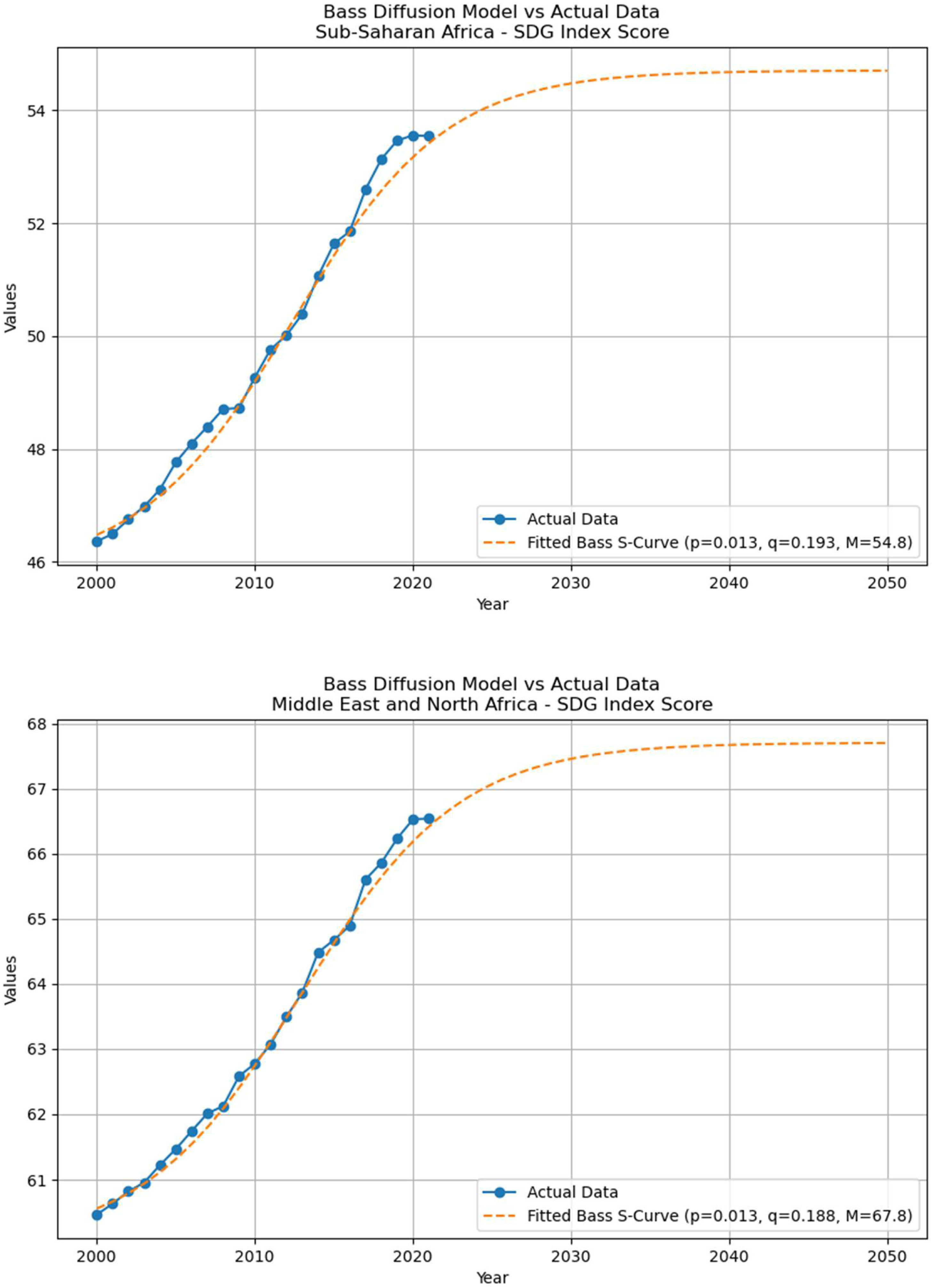

This study presents the first framework to predict SDG saturation levels at the country level (Fig. 1). It integrates NIEs’ governance and nonlinear dynamics for overall estimation of achievable sustainability goals. The study advances prior research by applying the Bass diffusion model to sustainability analysis for the first time. The Bass model quantifies SDG saturation time—the point when SDG progress nears its maximum (Bass, 1969)—and accounts for complex interdependencies and threshold effects overlooked by linear models. Findings show that the Bass model effectively describes national SDG progress by reinterpreting its parameters. SDG progress follows characteristic S-shaped curves: slow start, accelerated growth, and saturation phases. The framework fits most countries, except for 14 with complex instability that fail to show clear S-curves. The results reveal geographical and socioeconomic clusters with distinct SDG progress patterns. Innovation-driven policies, investment, and governance lead to earlier acceleration in SDG progress. High-income countries have higher innovation but lower saturation potential, being close to SDG ceilings, while low/middle-income countries face structural constraints, resulting in lower innovation and saturation potential.

Theoretical backgroundThe bass diffusion modelThe Bass diffusion model (Bass, 1969) helps in understanding innovation adoption processes within populations by analyzing commercial product uptake through its characteristic S-shaped adoption curve. This temporal pattern reflects the general transition from slow adoption to rapid acceleration and eventual market saturation across diverse innovation contexts. The model's theoretical foundation rests on two complementary adoption mechanisms: innovation-driven adoption (external influence parameter) and imitation-driven adoption (internal influence parameter).

It is important to situate the Bass model in relation to innovation diffusion theory, which conceptualizes the adoption of innovations through five adopter categories (innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards) and emphasizes the role of communication channels, social systems, and time in shaping diffusion patterns. Rogers’ framework is highly influential in providing a qualitative, sociological account of how innovations spread; however, it does not provide a direct quantitative mechanism for forecasting adoption dynamics or for estimating parameters from empirical data.

By contrast, the Bass model translates Rogers’ qualitative insights into a parsimonious mathematical formulation. This quantitative specification allows researchers to fit empirical time series, estimate country-specific parameters, and make predictions about saturation dynamics, which is essential for the analysis of SDG trajectories.

The adaptation of the Bass diffusion model to SDGs represents a paradigmatic shift toward complex socioinstitutional transformation processes (Wonglimpiyarat, 2025). As such, this recontextualization requires careful consideration of the unique characteristics that distinguish SDG implementation from traditional innovation diffusion (Kanie et al., 2014).

The innovation parameter in the SDG context encompasses exogenous drivers, including governmental policy frameworks, complex international agreements and multilateral initiatives, and institutional mandates that independently promote SDG-aligned practices (Khalik et al., 2024). These external influences are manifested through mechanisms such as renewable energy subsidies, carbon pricing policies, environmental regulations, and international development assistance programs (Bitencourt et al., 2021).

The imitation parameter captures endogenous social dynamics, including policy coherence, knowledge spillovers, normative convergence, and complex cross-border learning processes, that increase SDG implementation through peer effects (Li et al., 2023). This parameter encompasses regional adoption of successful sustainability models, South–South cooperation mechanisms, and knowledge transfer networks that facilitate the diffusion of best practices (Collste et al., 2017).

The market potential translates to SDG saturation potential, i.e., the maximum feasible level of sustainable development achievement a country can attain given its structural constraints (Marzouk et al., 2022). These constraints may include economic capacity, institutional quality, natural resource endowments, demographic characteristics, and geopolitical complexity and stability.

Hence, the adapted Bass diffusion model provides a theoretically grounded foundation for modeling SDG achievement trajectories across heterogeneous country contexts (Fu et al., 2020). Its reformulation—incorporating dynamic saturation potentials, country-specific heterogeneities, and complex system feedback—enables robust predictions of SDG saturation timing and identifies leverage points for accelerating global sustainability transitions.

The relationship between innovation ecosystems and SDGsWhile sustainable innovation ecosystems are increasingly framed as catalysts for the UN 2030 Agenda’s 17 SDGs (United Nations, 2015), their actual impact remains contingent on contested managerial and policy dynamics. Some scholars highlight multi-stakeholder collaboration (Nylund et al., 2021), digital tools (Dionisio et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2024), and policy incentives (Dmytrenko & Kuba, 2024) as drivers of socioeconomic and environmental progress, yet critics caution that structural barriers—including resource disparities, fragmented networks, and weak institutionalization (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024)—often dilute their transformative potential, revealing tensions between ecosystem rhetoric and implementation realities.

In fact, on the one hand, innovation ecosystems are aimed at: addressing climate change issues (SDGs 7, 13) by reducing CO₂ emissions through clean energy solutions and a circular economy (Brás & Robaina, 2024; George et al., 2020; Matos et al., 2022); achieving systemic collaboration (SDG 17) through multi-stakeholder partnerships exemplifying SDG-driven collaboration (Owen & Vedanthachari, 2022); implementing circular economy practices (SDG 12) for responsible production and consumption; supporting resilient supply chains and protecting biodiversity (SDGs 9, 15) through the sustainable use of natural resources (Albitar et al., 2023); scaling green innovations (SDG 9) such as digital/AI-driven solutions that cut emissions (George et al., 2020; Matos et al., 2022); addressing water scarcity worldwide (SDG 6) (Pandit & Sharma, 2023); promoting inclusive growth and reduced inequalities (SDG 10) by empowering SMEs and grassroots innovators (e.g., vertical farming startups) (Jütting, 2024; Mori et al., 2013; Song, 2025); enhancing policy implementation (SDG 16) like the EU Green Deal (Jütting, 2024); boosting economic competitiveness (SDG 8) as companies in sustainability ecosystems are 1.4 times more likely to achieve breakthroughs (Husainy et al., 2024); and fostering adaptive resilience (SDG 3) by ensuring good health and well-being (Mori et al., 2013; Pandit & Sharma, 2023).

By contrast, a strain of recent scientific literature highlighted possible negative impacts of innovation on the achievement of sustainability goals. For instance, in G7 countries, green innovation correlates negatively with SDG progress, particularly poverty eradication (SDG 1), due to high implementation costs displacing social investments (Islam, 2025). Circular innovations (e.g., textile recycling) advance SDG 12; however, they often prioritize economic efficiency over labor rights, undermining decent work (SDG 8) in supply chains (Berry et al., 2024; Islam, 2025). Digital innovation ecosystems in low-income countries exacerbate inequalities (SDG 10), as marginalized groups lack access to infrastructure, thereby worsening digital divides (Berry et al., 2024). Data-intensive innovations (e.g., AI) increase energy consumption (contradicting SDG 7) and carbon emissions, offsetting sustainability gains (Berry et al., 2024). Urban-centric innovation hubs widen rural–urban disparities (SDG 11), leaving rural communities behind in terms of access to healthcare (SDG 3) and education (SDG 4) (Yuan et al., 2023). Corporate-led innovation ecosystems, however, often prioritize profit over equity, sidelining SDGs 5 (gender equality) and 17 (partnerships) in governance (Berry et al., 2024). Pandemic-driven innovation (e.g., digital health), meanwhile, diverted resources from SDG 2 (zero hunger) and SDG 4 (education) in low-income regions (Henrysson et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2023). As for resource-intensive R&D, clean-tech innovations in high-income countries rely on rare-earth mining, violating SDG 15 (life on land) in extractive regions (Berry et al., 2024; Islam, 2025). National innovation policies (e.g., subsidies for tech startups) often neglect local SDG priorities, such as water security (SDG 6) in arid regions (Zhao et al., 2023). Cascading effects of tech-driven growth (e.g., e-commerce) increase consumption (SDG 12) but exacerbate waste and inequality (SDG 10) (Berry et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2023).

Data and methodologyDataThe dataset analyzed for this research is the online database for the Sustainable Development Report 2022 by Sachs et al. (2022), which is a yearly report that reviews the progress made periodically by UN member states with regard to the level of SDG achievement since their adoption. The data used for this study span 22 years, from 2000 to 2021, and the dataset contains 120 indicators covering the 17 SDGs, which generate the overall score for each country. Overall, 193 countries are included in the Sustainable Development Report 2022. The dataset includes several data on the SDGs, such as the overall results for all countries, including the index score, goal dashboard, and trend dashboard for all indicators and goals, spillover scores, raw values, normalized scores, dashboard ratings, trends, and goal scores. The SDG Index score and all other indicators are retroactively calculated across time using time series data. Missing data are treated by carrying forward time series data. Data come from international and rigorous organizations that operate extensive validation processes, like the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and the International Labour Organization. Therefore, the dataset characteristics limit any biases related to single-source utilizations, and the complete coverage of UN members avoids sample selection issues (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2024). Finally, the quality of the data ensures the reliability of the results.

The mathematical framework of the bass diffusion modelThe Bass diffusion model (Bass, 1969) is a mathematical framework for modeling the diffusion of innovation and new technologies over time. It describes cumulative adoption as an S-shaped curve (or S-curve), as the diffusion process starts slowly, initially accelerating until it fades out when it reaches the full market potential. Mathematically, the Bass model reads:

where F (t) is the cumulative fraction of adopters at time t; p represents the proportion of adopters driven by forces exogenous to the social dynamics of diffusion, such as advertisement or personal inclination towards innovation; and q represents the proportion of adopters driven by social pressure, i.e., the fact that many other people have adopted. The parameters p and q are referred toas an innovation parameter and an imitation parameter, respectively. Parameter M is the market potential, i.e., the total amount of adoption registered at the end of the process.The solution to this differential equation describes the S-curve, characterized by an initial period of slow adoption dominated by innovators, followed by rapid adoption driven by imitators, and finally a saturation phase when M is approached. The Bass model has traditionally been applied in contexts such as consumer product adoption, technology diffusion, and innovation management.

However, the overall flexibility of innovation diffusion models and theories—i.e., Bass, Rogers—enables adaptation to other domains where a diffusion-like process occurs (Wonglimpiyarat, 2025), including, for instance, innovative services and platforms in the urban mobility sector (Giglio & De Maio, 2022), electric vehicles (Brdulak et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022), and mobile banking services (Saeed & Xu, 2020). In this work, we have applied the Bass framework to data related to the SDGs for a large number of countries. The S-curve generated by the Bass model seems well suited to deriving insights into this process (Kanie et al., 2014). Similarly to innovation diffusion, national efforts toward SDG targets often begin slowly due to limited resources, institutional inertia, or other structural barriers, but over time, as progress accelerates through increased investment, policy implementation, and knowledge sharing, the rate of improvement may rise sharply before eventually stabilizing as the full potential of the country is approached.

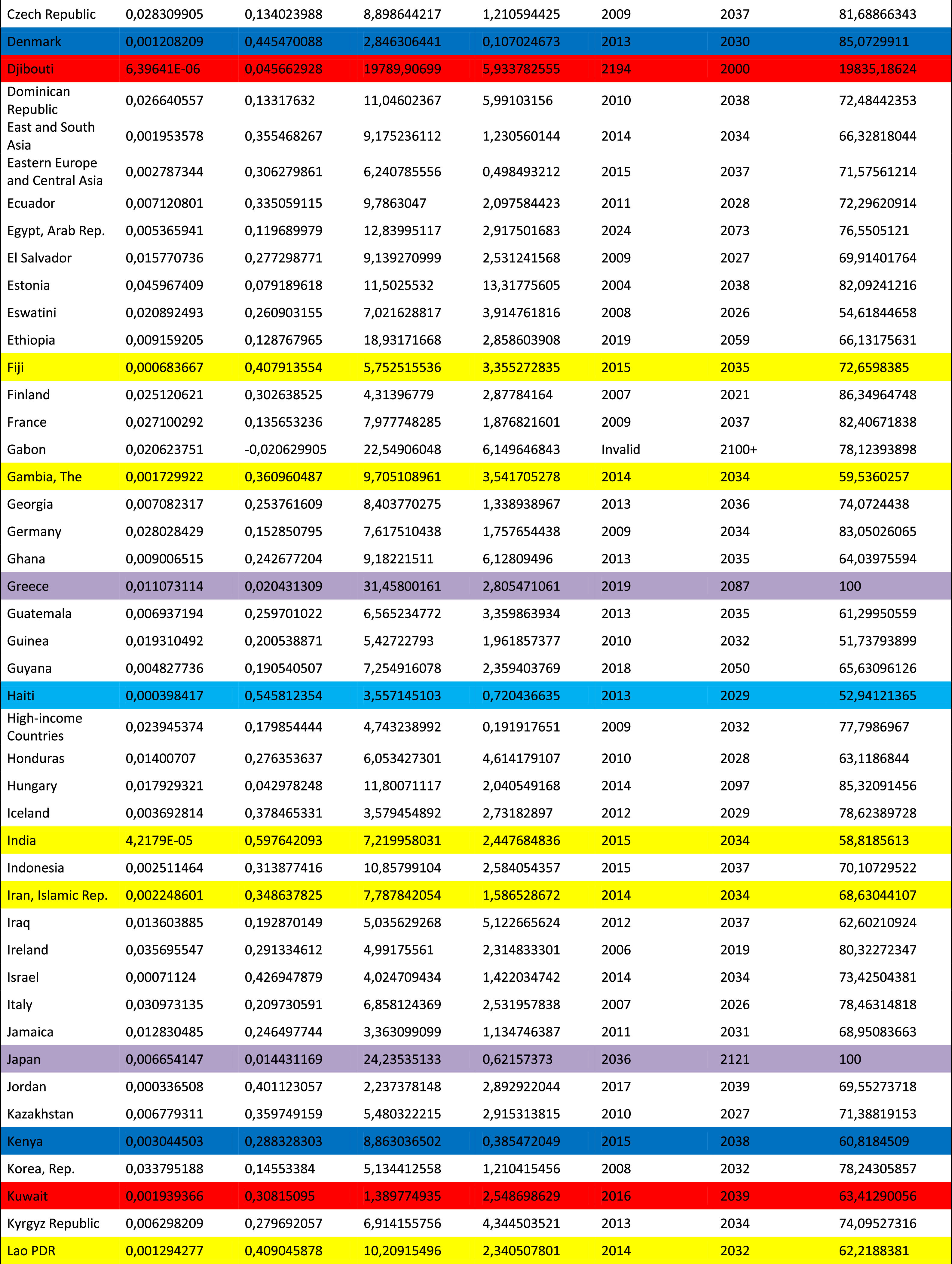

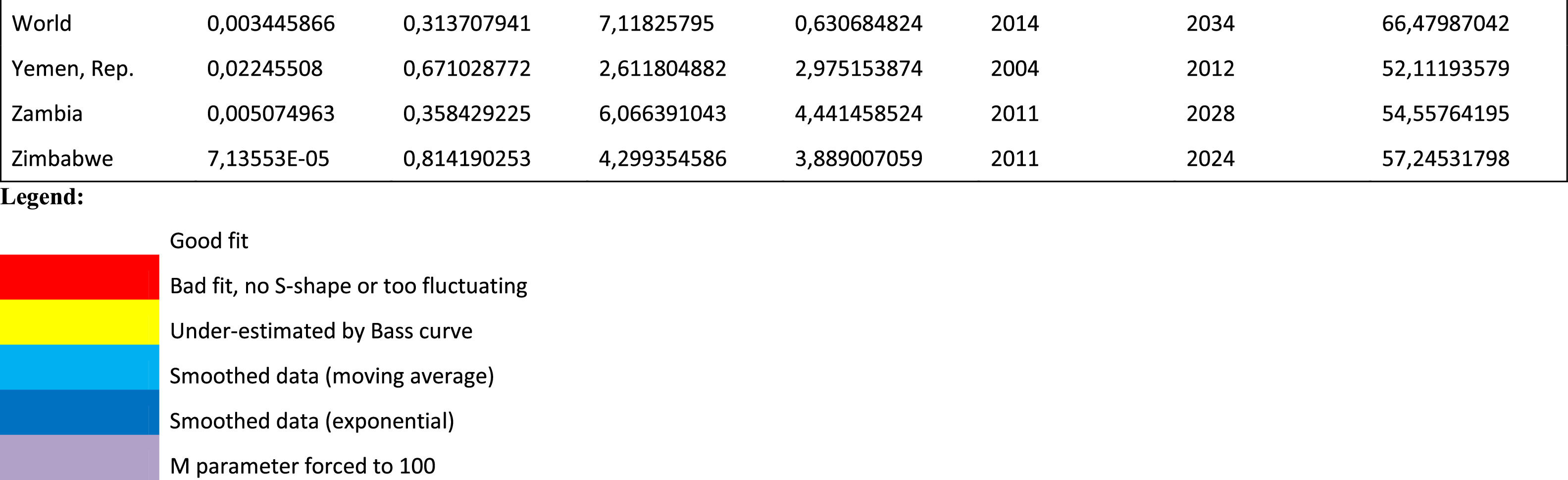

The adaptation of the bass diffusion modelTo carry out this analysis, we fitted the Bass curve (1) to the time series of the SDG results for each country. The dataset includes datasets for the aggregate SDG Index score as well as indicators for the 17 different goals. The database also contains highly granular data with time series for single measures contained in each goal, but no analysis has been carried out for these subgoals. The time span of the dataset covers 22 years, from 2000 to 2021, with one data point for each year corresponding to the level of fulfillment of the SDG on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. With respect to the SDG Index score time series, we performed a curve fitting of the S-curve produced by the Bass model using nonlinear least squares. In particular, this means searching for the set of parameters (p, q, M) that produces the S-curve that minimizes the squared difference between the curve itself and the data points of the time series. It should be noted here that the canonical Bass has null initial condition and grows to M. Hence, to apply the Bass framework in this case, we had to shift the SDG Index score properly and later readjust the fulfillment potential level M. Depending on the case and on the quality of the fitting, some precautions have been adopted to ensure the best fitting of the data points.

First, a Monte Carlo exploration of the space of the parameters was performed in case of an unsatisfactory result of the fitting for stiffer cases.

In some cases, the high fluctuations in the data resulted in poor fitting of the curve. In these cases, a moving average smoothing or an exponential smoothing was performed prior to the application of the least squares algorithm, depending on which led to the best performance.

For a minority of countries, the best fitting curve seems to underestimate the actual curve, likely due to idiosyncrasies in the trajectories of the Index score. For these countries, we applied a case-specific fine-tuning of the parameters—a common practice when fitting Bass curves to real data. For a small subset of countries, the time series appears highly linear. In these cases, the least squares method over the full set of parameters (p, q, M) led to a meaningless overestimation of parameter M, which far exceeded the cap value of 100. For these countries, we forced the market potential to 100.

Moreover, for some countries, the trajectory of the SDG Index score does not follow an S-shaped growth. For these nations, it is pointless to apply the described method as one cannot retrieve useful insights from the Bass framework. For each country, after having applied the corrections and assessed the best fit parameters, the time of the peak in the performance and the expected saturation time were computed. The former refers to the time—which can be either in the past or in the future—when the maximum increase in the year-to-year score is detected. Since this refers to the Bass S-curve rather than the real data, it is not influenced by random fluctuations in the dataset. The latter refers to the time in which the country is expected to reach a satisfactory proportion of its fulfillment potential. In this work, the satisfaction threshold for computing the saturation time is 100 %, but of course, this can be modified to be less demanding. This method can be applied in the same way to the time series for the single goals for the countries in the dataset. Due to these case-by-case exceptions, though, doing so is time-consuming. As a preliminary study, we report in the next section some results derived from the application of this method only to the aggregated SDG Index score. If needed, more granular analysis can be performed.

ResultsThe results are reported in Figs. 2a–e, 3a–g, and in the Appendix (Table A.1). Findings suggest that the Bass framework is well suited to explaining the majority of the trajectories in the fulfillment of the SDGs. As a very general remark, few countries do not exhibit a clear S-shaped trajectory (14 out of 177 entities), and they have often experienced very severe sociopolitical instability in recent decades. Another 12 countries show and underestimation by the Bass curve. The prediction for the remaining 151 countries does not present such issues, which suggests that the Bass paradigm can still be useful in this application even if it fails in some specific cases. Various clusterings, both geographical (East and South Asia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, etc.) and sociopolitical (low-income countries, OECD members, etc.), present some variability.

As for the parameter estimates and distributions, the Bass diffusion model revealed substantial heterogeneity across entities. The innovation parameter (p) demonstrated a mean value of 0.012705 with a range spanning from −0.004975 to 0.081554. The imitation parameter (q) exhibited a higher magnitude with a mean of 0.308457 and considerably wider variation, ranging from −1.087885 to 3.899236. The market potential parameter (M) showed extreme variability with a mean of 229.16 and a range extending from −2.92 to 19,789.91.

Geographical clusteringModel fit quality assessment based on the residual sum of squares (RSS) indicated mixed performance across entities. Excellent model fit (RSS < 1) was achieved for 29 entities (16.4 %), while good fit (RSS 1–2) characterized 35 (19.8 %). Moderate fit (RSS 2–3) was observed in 44 entities (24.9 %), and poor fit (RSS ≥ 3) affected 69 (39.0 %). The best-performing models included Denmark (RSS = 0.107025), the United States (RSS = 0.124277), Mauritius (RSS = 0.184018), high-income countries (RSS = 0.191918), and the Philippines (RSS = 0.230923). Conversely, the worst-performing models were Estonia (RSS = 13.317756), Venezuela (RSS = 11.644583), São Tomé and Príncipe (RSS = 10.460178), Angola (RSS = 7.248241), and Mauritania (RSS = 6.897939).

Several entities demonstrated parameter estimates that deviate from theoretical expectations. One entity (South Sudan) exhibited a negative innovation parameter, while five (Azerbaijan, Cuba, Gabon, Luxembourg, and South Sudan) showed negative imitation parameters. Three entities (the Central African Republic, Syria, and Venezuela) yielded negative market potential estimates, and two (Djibouti and New Zealand) displayed extremely high market potential values exceeding 19,000, indicating potential overfitting or data quality concerns.

Socioeconomic clusteringA comparison between estimated market potential (M) and actual market potential (M_real) revealed some underestimation across the dataset. No entities demonstrated overestimation with ratios exceeding 2.0. The highest innovation parameter was observed in Cuba (p = 0.081554), while Barbados exhibited the highest imitation parameter (q = 3.899236), and Djibouti demonstrated the highest estimated market potential (M = 19,789.91). These extreme values suggest either unique diffusion dynamics or potential model specification issues requiring further investigation case by case.

Peak adoption years ranged from 1995 to 2194, with a median peak year of 2012. Saturation years spanned from 2000 to 2198, with a median saturation year of 2033. Four out of 177 entities exhibited invalid peak estimates (Azerbaijan, Cuba, Gabon, and Luxembourg), while three showed saturation projections beyond 2100 (Cuba, Gabon, and Luxembourg). This shows the overall validity of the Bass model application.

Regional aggregates and income-based groupings generally demonstrated better model fit than individual countries, with high-income countries and OECD members being among the top-performing entities. This pattern suggests that aggregated data may smooth individual country volatility and provide more stable parameter estimates for Bass model application.

The minor proportion of entities with poor model fit indicates that the standard Bass diffusion model may have relevant applicability to SDG Index score diffusion patterns. By contrast, those cases presenting an underestimation of market potential and the occurrence of negative parameter values suggest that SDG achievement dynamics sometimes does not conform to traditional product diffusion assumptions, necessitating model modifications or alternative theoretical frameworks for accurate representation of SDG adoption patterns.

DiscussionClustering analyses based on socioeconomic and geographic criteria reveal nuanced and complementary insights into the diffusion and saturation patterns of SDGs across countries and regions. Socioeconomic clustering distinctly segments countries into developmental tiers–high-income, middle-income, and low-income groups–reflecting fundamental differences in economic capacity, institutional quality and complexity, and human capital that critically shape SDG achievement trajectories. This finding aligns with research emphasizing that sustainable innovation ecosystems and SDG progress are deeply contingent on economic wealth, education, and institutional robustness and complexity, which drive innovation capacity and imitation effects (Dmytrenko & Kuba, 2024; Nylund et al., 2021). The heterogeneity in Bass diffusion model parameters across socioeconomic clusters supports the hypothesis that these foundational conditions strongly influence the pace and extent of SDG adoption.

Geographic clustering highlights regional cohesion and policy spillovers, reflecting shared cultural, political, and environmental contexts that facilitate knowledge transfer and normative convergence (Owen & Vedanthachari, 2022). However, the persistence of substantial intraregional disparities indicates that geographic proximity alone cannot overcome complex structural barriers such as resource disparities, governance fragmentation and complexity, and social inequality (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024). This confirms critiques in the literature that ecosystem collaboration rhetoric often confronts complex implementation challenges due to uneven capacities and institutional weaknesses (Berry et al., 2024). Thus, while regional cooperation mechanisms (SDG 17) can catalyze diffusion through multi-stakeholder partnerships and policy harmonization (Owen & Vedanthachari, 2022), the underlying socioeconomic context remains the predominant determinant of SDG diffusion success.

The clustering results further suggest that high-income countries and OECD members, which cluster socioeconomically, exhibit stronger Bass model fits and greater saturation potential, reflecting their advanced innovation ecosystems and complex policy infrastructures (Husainy et al., 2024; Jütting, 2024). Conversely, many low-income countries, even when geographically proximate to better-performing neighbors, remain in lower diffusion clusters, in line with documented digital divides and resource constraints that exacerbate SDG inequalities (Yuan et al., 2023). This supports the hypothesis that innovation ecosystems, while pivotal for progress on climate action (SDGs 7, 13), a circular economy (SDG 12), and inclusive growth (SDG 10), are highly contingent on overcoming structural barriers (Brás & Robaina, 2024; Song, 2025).

Moreover, the clustering patterns may reflect the uneven spatial distribution of innovation benefits, where urban-centric innovation hubs concentrate resources and capabilities, leaving rural and marginalized populations behind, thus reinforcing spatial inequalities (Yuan et al., 2023). Digital innovation ecosystems in low-income clusters may exacerbate social exclusion due to infrastructural deficits, limiting the imitation-driven diffusion of sustainable practices. The findings also highlight the risk of misaligned national innovation policies that neglect local SDG priorities, such as water security or biodiversity conservation, which are critical in resource-constrained regions (Albitar et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

Importantly, these results echo the dual nature of innovation ecosystems described in recent literature. On the one hand, innovation ecosystems foster systemic collaboration (SDG 17), green technology scaling (SDG 9), and adaptive resilience (SDG 3) through multi-stakeholder partnerships, digital tools, and policy incentives (Dmytrenko & Kuba, 2024; Liao et al., 2024; Nylund et al., 2021). On the other hand, they may inadvertently exacerbate inequalities (SDG 10), environmental trade-offs (SDGs 7, 15), and social exclusion, particularly in low-income and marginalized contexts (Berry et al., 2024; Islam, 2025). For example, green innovations in G7 countries have been found to correlate negatively with poverty eradication due to high costs displacing social investments (Islam, 2025), a dynamic that may be reflected in the clustering of diffusion parameters.

In summary, the clustering analyses substantiate the complex interplay between socioeconomic capacity and geographic factors in shaping SDG diffusion pathways. They confirm that while innovation ecosystems are critical enablers of the 2030 Agenda, their transformative potential is mediated by multilevel governance dynamics, resource distribution, and equity considerations (Dionisio et al., 2023; Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024; United Nations, 2015). These insights suggest that effective policy interventions should simultaneously strengthen socioeconomic foundations and foster regional cooperation to accelerate equitable and widespread diffusion of sustainable development innovations across the globe.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates that the Bass diffusion model can be effectively adapted to analyze national progress toward Sustainable Development Goals, capturing the characteristic S-shaped adoption curves of SDG achievement across diverse countries. The model’s parameters reveal significant heterogeneity influenced by socioeconomic and geographic factors, reflecting the complex dynamics of innovation ecosystems. While high-income countries tend to approach saturation earlier, lower-income nations face structural constraints limiting their SDG fulfillment potential. These findings highlight the importance of innovation ecosystems and governance in accelerating sustainable development. Overall, the Bass model provides a valuable quantitative framework for forecasting SDG saturation timing and informing policy interventions.

Theoretical implicationsThe application of the Bass diffusion model in this study extends its traditional use from product and technology adoption to the complex domain of achieving SDGs at the national level (Bass, 1969; Wonglimpiyarat, 2025). The model’s foundational premise—that adoption dynamics arise from two complementary mechanisms, namely innovation-driven external influences and imitation-driven internal social interactions—offers a parsimonious yet powerful lens through which to understand the nonlinear progression of SDG fulfillment (Kanie et al., 2014). By reinterpreting the market potential parameter as the SDG saturation potential, this adaptation accounts for structural constraints and capacities that are unique to each country, such as economic resources, institutional quality, and geopolitical stability (Marzouk et al., 2022).

Theoretically, this reformulation bridges innovation diffusion theory with complexity science by acknowledging that SDG progress emerges from the interplay of multiple heterogeneous agents within national innovation ecosystems (Breslin et al., 2021; Ponta et al., 2023). These ecosystems are characterized by adaptive, nonlinear feedback loops among governments, firms, and civil society actors, which influence the acceleration and eventual saturation of sustainable development efforts (Reed et al., 2025; Toth et al., 2024). The Bass model’S-shaped curve effectively captures the transition from initial slow progress—often hindered by institutional inertia and resource limitations (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024)—to rapid acceleration driven by policy coherence, knowledge spillovers, and normative convergence (Collste et al., 2017; Li et al., 2023), culminating in a plateau as countries near their fulfillment ceilings.

Moreover, the model’s parameters provide insight into the relative strength of external policy drivers versus internal social dynamics across different socioeconomic and geographic clusters, highlighting the importance of context-dependent governance frameworks (Husainy et al., 2024; Nylund et al., 2021). This aligns with the emphasis of complexity theory on emergent behaviors arising from microlevel interactions within complex adaptive systems (Granstrand & Holgersson, 2020; Miller et al., 2024). While the Bass model simplifies some aspects of these interactions by aggregating adopters, its successful application here suggests that even relatively simple diffusion models can yield meaningful insights into complex socioinstitutional transformations when carefully adapted.

Theoretically, this study invites further integration of the Bass framework with network-based and agent-based models that explicitly capture heterogeneity and multilevel interactions (Zhang et al., 2024; Zhou & Li, 2024), enhancing the understanding of how innovation ecosystems evolve and influence SDG trajectories. It also underscores the need to consider dynamic saturation potentials and threshold effects to better reflect the evolving capacities and constraints within innovation ecosystems. In sum, this work contributes to the theoretical literature by demonstrating the Bass model’s flexibility and relevance for modeling complex, multi-actor sustainability transitions in national contexts.

Practical implicationsFrom a practical standpoint, the adapted Bass diffusion model offers policymakers, innovation managers, and development practitioners a quantitative tool for forecasting the timing and extent of national SDG achievement, enabling more informed strategic planning (Sachs et al., 2024). By estimating the innovation and imitation parameters, decision-makers can discern the relative impact of external policy initiatives versus internal social dynamics, guiding the allocation of resources and the design of interventions to accelerate sustainable development (Dmytrenko & Kuba, 2024; Nylund et al., 2021).

For instance, a higher innovation parameter suggests that strengthening external drivers—such as regulatory frameworks, subsidies for green technologies, and international cooperation—can effectively stimulate early SDG adoption (Bitencourt et al., 2021; European Commission, 2023). Conversely, a higher imitation parameter highlights the critical role of endogenous factors like peer learning, knowledge spillovers, and regional cooperation networks, suggesting that fostering collaborative governance and multi-stakeholder partnerships can increase progress (Collste et al., 2017; Owen & Vedanthachari, 2022). Understanding these dynamics allows governments to tailor policies to their specific contexts, focusing on either enhancing policy incentives or facilitating social diffusion mechanisms (Dionisio et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2024).

The ability of the model to predict saturation times also assists in setting realistic targets and monitoring progress, as it helps to identify countries or regions at risk of stagnation due to structural barriers or governance challenges (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2023). This insight supports the prioritization of capacity-building efforts, institutional reforms, and investment in innovation ecosystems where they are most needed (Jütting, 2024; UNDP, 2024). Furthermore, recognizing the heterogeneity of diffusion patterns across socioeconomic clusters enables international organizations and donors to customize support strategies, addressing disparities between high-income and low-income countries (World Bank, 2024).

In addition, the Bass model’s framework can inform private sector actors and innovation hubs by signaling market readiness and potential demand for sustainable technologies, thereby optimizing investment decisions and scaling strategies (Husainy et al., 2024; Song, 2025). It also aids in anticipating the impact of disruptive events or policy shocks on SDG trajectories, enabling the use of adaptive management in complex and uncertain environments (Reed et al., 2025).

Overall, this practical application of the Bass diffusion model equips stakeholders with a robust, data-driven approach to enhance coordination, improve policy coherence, and accelerate the diffusion of sustainability innovations within national innovation ecosystems, ultimately advancing the global 2030 Agenda (Nylund et al., 2021; United Nations, 2015).

Limitations and future research directionsDespite its valuable insights, this study acknowledges several limitations inherent in applying the Bass diffusion model to complex socioinstitutional phenomena like SDG achievement. The model’s assumption of homogeneous adopter populations and constant parameters over time simplifies the diverse and evolving nature of national innovation ecosystems. Some countries exhibited poor model fit or anomalous parameter estimates, reflecting sociopolitical instability or data quality issues that the model cannot fully capture.

Moreover, the model used in this research needs to be complemented by Rogers’ model when considering investigating the maturity stages of a subgroup of more consolidated innovation ecosystems as well as the consequences of for platform design and governance (Rogers, 2003; Rogers et al., 2014; Springer et al., 2025).

Future research should explore methodological enhancements by integrating the Bass framework with agent-based and network diffusion models to explicitly represent heterogeneous actors, multilevel governance structures, and dynamic feedback loops. Incorporating time-varying parameters would enable the model to better reflect changing policy environments, shocks, and adaptive behaviors. Additionally, leveraging richer, higher-frequency data sources, such as real-time policy implementation metrics or social network analyses, could improve parameter estimation and model validation.

Further empirical studies could extend the analysis to subnational levels or specific SDGs to uncover more granular diffusion patterns and contextual factors. Investigating the interplay between innovation ecosystems and negative externalities, such as inequality or environmental trade-offs, would also deepen understanding of the “dark side” of innovation.

Additional research is needed to uncover the differences in sustainability-related dynamics, governance patterns, and structural factors of B2B innovative industrial ecosystems vs B2C ones, thus calling for a multigroup comparison of B2B vs B2C ecosystems (Springer et al., 2025; see also Ritala & Jovanovic, 2024).

Future research efforts should also be devoted to coordination-level efforts in platform ecosystems and innovation ecosystems in general, with a view to grand challenge resolution. Possible research questions to address include: (1) How can pro-environmental or prosocial actors be combined with profit-oriented ones in innovation ecosystems?; (2) How can these different kinds of actors be incentivized?; (3) How can brokerage among those actors help in reducing the overall complexity and uncertainty in innovation ecosystems? (Ritala, 2024; see also Samuelson, 1974).

Finally, interdisciplinary approaches combining complexity science, behavioral economics, and sustainability transitions theory hold promise for refining theoretical frameworks and developing more comprehensive models to guide policy and practice in achieving sustainable development.

FundingThis work was partly supported by:

- -

The Ministry of Science and Technology of China through the University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, P.R. China (Project number: DL2023200001L, project title: “Research on Regional Innovation Ecosystem of China in the New era”).

- -

The Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education - CAPES under the PRINT - Institutional Internationalization Program through the University of São Paulo, Brazil (Project number: 88,887.936506/2024–00).

Giacomo Masali: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Donato Morea: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Carlo Giglio: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Gianpaolo Iazzolino: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Guido Perboli: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Maria Elena Bruni: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

We have nothing to declare.