Severe asthma is a complex, heterogeneous condition that can be difficult to control despite currently available treatments. Multidisciplinary severe asthma units (SAU) improve control in these patients and are cost-effective in our setting; however, their implementation and development can represent an organizational challenge. The aim of this study was to validate a set of quality care indicators in severe asthma for SAU in Spain.

MethodsThe Carabela initiative, sponsored by SEPAR, SEAIC, SECA and SEDISA and implemented by leading specialists, analyzed the care processes followed in 6 pilot centers in Spain to describe the ideal care pathway for severe asthma. This analysis, together with clinical guidelines and SEPAR and SEAIC accreditation criteria for asthma units, were used to draw up a set of 11 quality of care indicators, which were validated by a panel of 60 experts (pulmonologists, allergologists, and health-policy decision-makers) using a modified Delphi method.

ResultsAll 11 indicators achieved a high level of consensus after just one Delphi round.

ConclusionsExperts in severe asthma agree on a series of minimum requirements for the future optimization, standardization, and excellence of current SAUs in Spain. This proposal is well grounded on evidence and professional experience, but the validity of these consensus indicators must be evaluated in clinical practice.

El asma grave es una enfermedad compleja, heterogénea, y difícil de controlar a pesar de los tratamientos disponibles. Las unidades multidisciplinares de asma grave (UAG) mejoran el control en los pacientes, siendo coste-efectivas en nuestro medio; sin embargo, su creación y mejora pueden suponer un reto organizativo. El objetivo del estudio fue validar un conjunto de indicadores de calidad asistencial para las UAG en España.

MétodoLa iniciativa Carabela, promovida por la SEPAR, la SEAIC, la SECA y la SEDISA, y llevada a cabo bajo el liderazgo clínico especializado, ha analizado los procesos de 6 centros piloto en España para caracterizar el modelo asistencial ideal para el asma grave. Partiendo de este análisis, de las guías clínicas y los criterios de acreditación de las unidades de asma de la SEPAR y de la SEAIC, se ha elaborado un listado de 11 indicadores de calidad asistencial en asma grave, centrados en aspectos considerados básicos de la atención a estos pacientes. Dichos indicadores se han validado a través de una metodología Delphi modificada con un panel multidisciplinar de 60 expertos (neumólogos, alergólogos y gestores sanitarios).

ResultadosTodos los indicadores alcanzaron un nivel alto de consenso en una sola ronda Delphi.

ConclusionesLos profesionales expertos en asma grave están de acuerdo en que existan una serie de requerimientos mínimos para una futura optimización, homogeneización y excelencia de la actuales UAG en España. Si bien se trata de una propuesta bien fundamentada, es necesario poner a prueba estos indicadores en la práctica clínica para validar su funcionamiento.

Severe asthma is characterized by the need for multiple drugs and high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (steps 5–6 of the Spanish Asthma Management Guidelines 5.2 [GEMA]1 and 5 of the Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA] guidelines).2 This classification is applicable to both patients with controlled and uncontrolled asthma and is associated with increased resource consumption and healthcare costs.1–5 This is a complex, heterogeneous disease, and the range of pathological manifestations and characteristics is reflected in different phenotypes that involve various clinical, functional, and quality-of-life parameters and associated comorbidities.1,6

In 2019, asthma affected 262 million people worldwide7 and was the most prevalent respiratory disease. About 5–10% of this overall population would meet the criteria for severe asthma, although prevalence of this classification varies between geographical areas, and in Western Europe accounts for 18% of cases.8,9 Despite the many therapeutic advance made in recent decades, it is estimated that, in our setting, more than half of patients present persistently poor or partial disease control10–12; specifically, only 13.6% of Spanish asthma patients are thought to achieve good disease control. Poor control is closely correlated with undertreatment, poor adherence to maintenance therapy, poor inhalation technique, the presence of aggravating and precipitating factors, certain associated comorbidities, and disease severity.11,12 The ASMACOST study determined that asthma expenditure accounts for 2% of total public health expenditure (1.48 billion euros per year), of which 70% is attributed to poor disease control. Severe uncontrolled asthma alone accounts for half of the financial resources allocated to the management of this disease.11,12

If we are to offer excellence in the care of patients with severe asthma and achieve maximum possible control, we must take a cross-sectional, multidisciplinary approach to this disease.1,13,14 For this reason, the 2018 SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery), consensus on severe asthma in adults and its 2020 update recommend referring patients with severe asthma to dedicated, specially equipped units staffed by expert healthcare personnel.6 There is therefore a growing demand for reference units offering integrated care, coordinated diagnostic tests, and innovative therapies in many healthcare facilities, particularly now that these units have clearly demonstrated their cost-effectiveness and efficacy in the control of severe asthmatic patients.15,16 This, however, can be an organizational challenge.

Against this background, the Carabela project, sponsored by SEPAR, SEAIC (Spanish Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology), SEDISA (Spanish Society of Health Managers), and SECA (Spanish Society of Quality of Care) and implemented by leading specialists from these societies, was created with the initial aim of analyzing the care model for severe asthma and identifying unmet needs and opportunities to develop a more coordinated and efficient model.17 This led to the definition of specific health care quality indicators for asthma management that would help evaluate the outcomes of initiatives for improvement. In this paper, we describe the development and validation by multidisciplinary consensus of various healthcare quality indicators in severe asthma.

MethodsPrevious characterization of care processes in severe asthmaWe used a process-reengineering method to define an appropriate care model that meets the needs of patients with severe asthma by detecting unmet needs and taking advantage of opportunities that promote the development of a more coordinated and efficient standard of care. When extrapolated to the health sector, process reengineering can be defined as a set of interventions designed to change the healthcare model by increasing its efficiency and improving quality while reducing costs.18

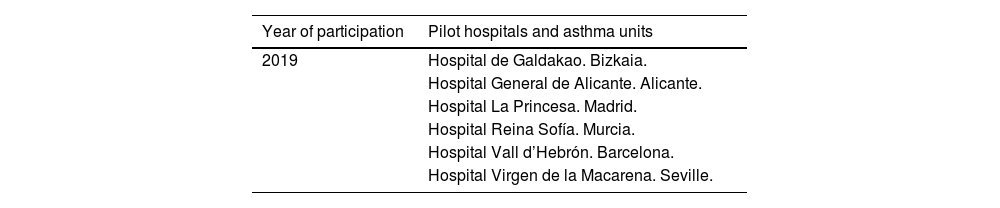

In the initial phase, Lean methodology adapted to healthcare settings was used to define the “ideal asthma unit”.19 This innovative approach to managing care processes eliminates any activities that are counterproductive or hinder the workflow by way of a critical review designed to reconfigure processes, minimize inefficiencies, and generate value in a cost-effective manner. Between 2019 and 2020, we conducted a pilot survey in 6 Spanish health centers to investigate care models in patients with severe asthma (Table 1). After careful analysis of the various models, we identified up to 144 areas for improvement, for which 112 possible solutions were proposed. The aim of the Carabela project was to perfect a multidisciplinary, comprehensive model of care in patients with severe asthma, to achieve excellence in outcomes, and to improve the efficiency and efficacy of care processes from both a clinical and a healthcare management perspective. Details of the objectives and initial development of the Carabela project have been published elsewhere.17

Spanish pilot hospitals participating in the Carabela project.

| Year of participation | Pilot hospitals and asthma units |

|---|---|

| 2019 | Hospital de Galdakao. Bizkaia. |

| Hospital General de Alicante. Alicante. | |

| Hospital La Princesa. Madrid. | |

| Hospital Reina Sofía. Murcia. | |

| Hospital Vall d’Hebrón. Barcelona. | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Macarena. Seville. |

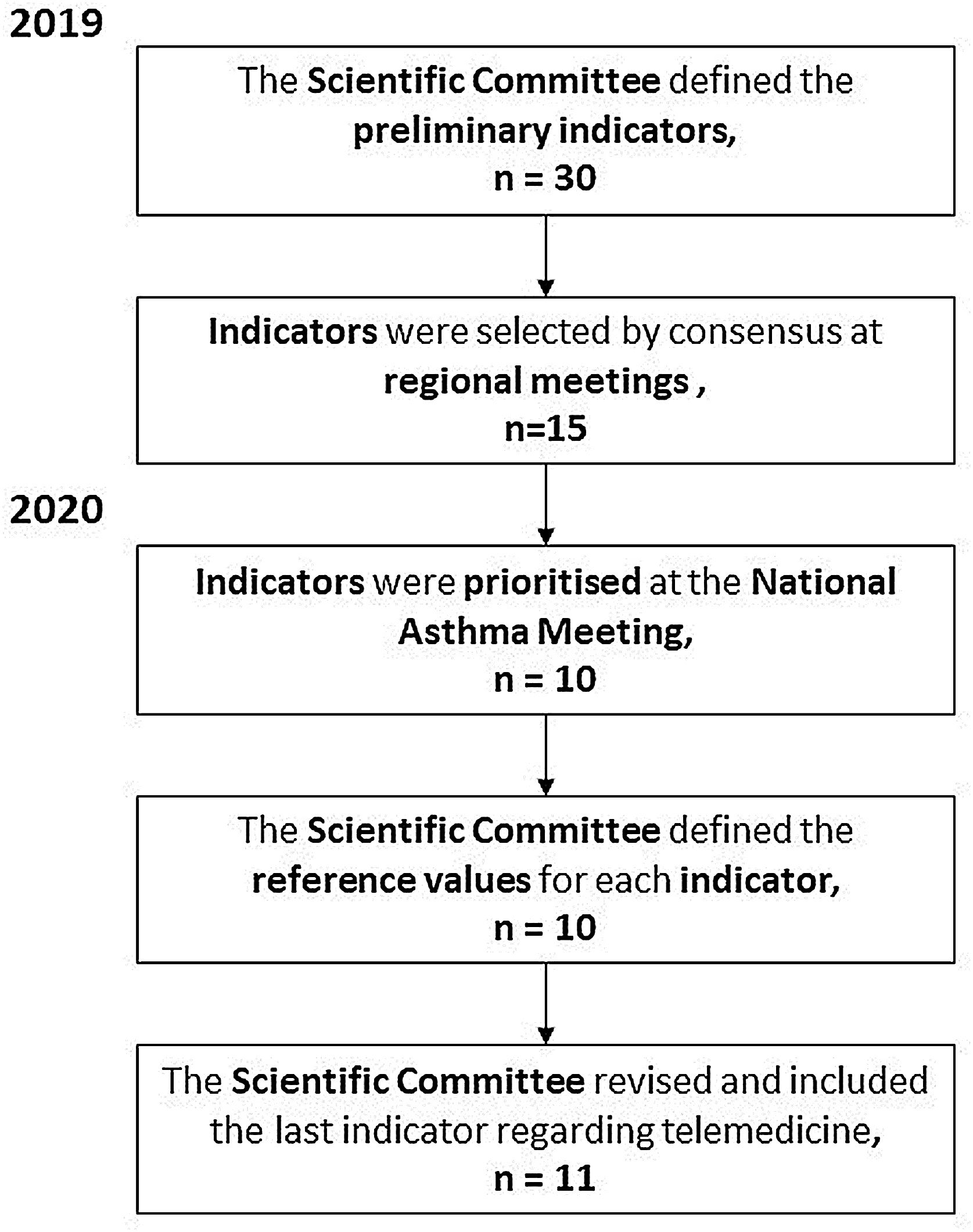

In a subsequent phase, we selected and developed a series of healthcare quality indicators to measure changes associated with the process of creating and improving asthma units (Fig. 1). To this end, the coordinating committee collected of a wide range of data derived from analyses and reports on the management of severe asthma in pilot centers, reviewed SEPAR20 and SEAIC21 accreditation criteria for Severe Asthma Units and clinical practice guidelines,1,2 and took into consideration the opinion of asthma experts attending the National Asthma Meeting and various regional meetings and the personal experience of the members of the scientific and steering committee of the Carabela project. To summarize, multiple sites were involved in developing and selecting this first block of indicators, with the participation of hospitals and asthma units throughout Spain. In 2019, the project coordinating committee drew up a preliminary list of indicators that was evaluated and discussed by 100 specialists, including pulmonologists, allergologists, nurses, and hospital pharmacists from 61 sites during 6 regional meetings held in hospitals in Andalusia, Extremadura, Canary Islands, Galicia, Asturias, Madrid, the Basque Country, Catalonia, Castile and Leon, and Valencia. At these meetings, an initial set of indicators was defined and then prioritized in a face-to-face meeting, using the Mentimeter tool,22 a web application with different interactive formats designed to promote audience engagement and participation. The coordinating committee proposed and defined the reference values at successive meetings. They also subsequently added a new item to the list agreed at the national meeting.

Modified Delphi consensus procedureAll selected indicators were submitted to consensus using a modified Delphi methodology. This is a predictive, intuitive, dynamic system, based on strategic analysis of the opinions of a panel of experts on a particular topic (in this case, severe asthma), with the aim of making sound decisions and defining specific solutions to a specific problem. The consensus on the final quality indicators was based on the Rand Healthcare Corporation and the University of California, Los Angeles (Rand/UCLA) appropriateness method.23

The coordinating committee responsible for developing the Delphi questionnaire based on 11 selected indicators was made up of 9 experts from the Carabela project.

After developing and defining healthcare quality indicators, 25 members of SEPAR and SEAIC, and 5 from SECA and SEDISA, nominated by their societies according to their experience in the management of severe asthma, were invited to participate.

Panelists evaluated the indicators proposed in the Delphi questionnaire anonymously using an interactive platform.24 Participants were asked to classify and rate each indicator on a 9-point Likert scale indicating their agreement or disagreement (1=strongly disagree; 9=strongly agree).25 Statements were classified as inappropriate, uncertain, or appropriate when a median score of 1–3, 4–6, or 7–9, respectively, was recorded. An indicator reached consensus if at least two thirds of the panel rated it within the range containing the median; otherwise it did not reach consensus. If more than one third of the individual scores were within the range that did not contain the median, it was considered controversial. All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 3.2.5.

ResultsInitial list of quality indicatorsA preliminary list of 30 indicators defined by the Project Coordinating Committee after the regional meeting was drawn up, and 15 were selected (Supplementary Material, Table A) with an average degree of consensus of 7.89 out of 10.22 At the 2020 National Asthma Meeting, these 15 indicators were reviewed, prioritized, and refined to a final set of 10 indicators. Finally, in 2020, following the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the coordinating committee added a new indicator to address the use of telemedicine in patients with severe asthma, leaving a set of 11 items to be proposed for consensus. Fig. 1 shows the process used in the Carabela project to develop and select the recommended quality indicators for SAU. The Project Coordinator Committee awarded reference values to each indicator to validate the degree of compliance.

Delphi consensus resultsAll 60 experts invited to participate in the Delphi panel agreed to collaborate. The average experience of the panelists was 22 (SD 8.93) years, with a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 40 years of experience. Participants’ practices represented a large part of the Spanish territory (Table A).

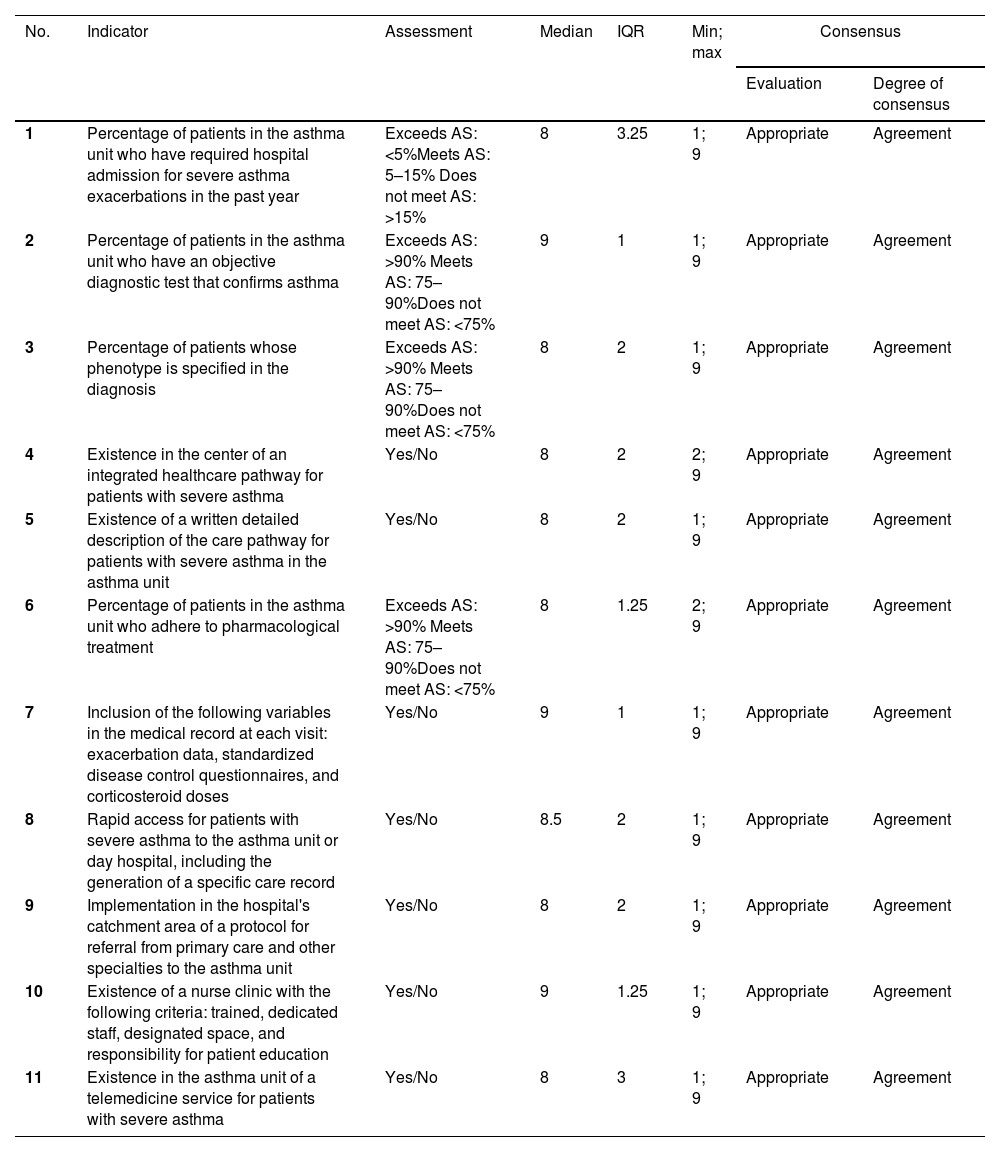

All indicators scored a median of 8 points or more during the first round, so a second round of voting was not required (Table 2). This result indicates that the panel of experts considers the proposed indicators appropriate for measuring the quality of care for severe asthma in asthma units in Spain.

Delphi questionnaire indicators and results.

| No. | Indicator | Assessment | Median | IQR | Min; max | Consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation | Degree of consensus | ||||||

| 1 | Percentage of patients in the asthma unit who have required hospital admission for severe asthma exacerbations in the past year | Exceeds AS: <5%Meets AS: 5–15% Does not meet AS: >15% | 8 | 3.25 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 2 | Percentage of patients in the asthma unit who have an objective diagnostic test that confirms asthma | Exceeds AS: >90% Meets AS: 75–90%Does not meet AS: <75% | 9 | 1 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 3 | Percentage of patients whose phenotype is specified in the diagnosis | Exceeds AS: >90% Meets AS: 75–90%Does not meet AS: <75% | 8 | 2 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 4 | Existence in the center of an integrated healthcare pathway for patients with severe asthma | Yes/No | 8 | 2 | 2; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 5 | Existence of a written detailed description of the care pathway for patients with severe asthma in the asthma unit | Yes/No | 8 | 2 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 6 | Percentage of patients in the asthma unit who adhere to pharmacological treatment | Exceeds AS: >90% Meets AS: 75–90%Does not meet AS: <75% | 8 | 1.25 | 2; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 7 | Inclusion of the following variables in the medical record at each visit: exacerbation data, standardized disease control questionnaires, and corticosteroid doses | Yes/No | 9 | 1 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 8 | Rapid access for patients with severe asthma to the asthma unit or day hospital, including the generation of a specific care record | Yes/No | 8.5 | 2 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 9 | Implementation in the hospital's catchment area of a protocol for referral from primary care and other specialties to the asthma unit | Yes/No | 8 | 2 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 10 | Existence of a nurse clinic with the following criteria: trained, dedicated staff, designated space, and responsibility for patient education | Yes/No | 9 | 1.25 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

| 11 | Existence in the asthma unit of a telemedicine service for patients with severe asthma | Yes/No | 8 | 3 | 1; 9 | Appropriate | Agreement |

Exceeds AS: assessment exceeds minimum requirement to meet accreditation standards; Meets AS: assessment meets accreditation standards; does not meet AS: assessment does not meet minimum accreditation standards. IQR: interquartile range.

This study, led by clinical specialists, helped identify unmet needs and define specific quality indicators for severe asthma. These indicators can be used to evaluate fundamental elements in the care process of severe asthma: hospital admissions, objective diagnostic asthma tests, phenotyping, therapeutic adherence and inhalation technique, monitoring of exacerbations, use of systemic corticosteroids, and primary care referral protocols, to mention the most important. With regard to the care system in each center, 2 of the selected indicators assess the existence of integrated processes and access to intervention protocols in patients with severe asthma. Finally, 2 of the indicators assess the existence of a telemedicine service for patients with severe asthma and an asthma unit nurse clinic with dedicated and qualified personnel.

All indicators achieved a high level of consensus in a single Delphi survey round. Thus, the specialists involved in the management of patients with severe asthma agree that a series of minimum requirements must be met to optimize, standardize, and achieve excellence in SAUs in Spain, and that these indicators may serve as a paradigm for the future.

Quality indicators help evaluate the performance of the care model and the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, and constitute quantitative and qualitative methods to identify and disseminate best care practices.26,27 Their use is becoming increasingly widespread,27 and some have been generated from multidisciplinary consensus procedures. In fact, the GEMA guidelines include the conclusions of a proposal for disease management indicators,28 and quality indicators for appropriate care of asthma exacerbations in the emergency department have also been proposed.29 Criteria for the referral of asthma patients from the emergency department and primary care have also been defined.29,30

In recent years, various projects to improve the care of both adults and children with severe asthma by using quality indicators have emerged.28,31 However, no specific quality indicators are yet available for the care of patients with severe asthma. The aim of the Carabela project was to perfect a multidisciplinary, comprehensive model of care in patients with severe asthma, to achieve excellence in outcomes, and to improve the efficiency and efficacy of care processes from both a clinical and a healthcare management perspective.17 For this reason, we believe it is important to have a tool that will help us assess the development and implementation of asthma units, and thus ensure our patient receive the best possible care.

The basic indicators described here will help guide the different centers in their efforts to improve. They can also be used to evaluate the impact of the measures implemented, and therefore mark the first step toward standardization and optimization of the healthcare process in patients with severe asthma in Spain.17

We believe that the implementation of the basic indicators described here will help Spanish hospitals achieve an overall improvement in the clinical care of patients with severe asthma and evaluate their results. Implementing these indicators is the first step toward standardization, optimization, and universalization of care pathways for this highly prevalent respiratory disease in Spain.

The main strengths of the Carabela project lie primarily in its multicenter design, with participants representing a large part of the Spanish territory. As a result, we were able to investigate how a wide range of hospitals approach the management of severe asthma. The project has also received institutional support from 4 leading scientific societies (SEAIC, SECA, SEDISA, and SEPAR) in Spain, and the participation of specialists from these societies has given the initiative both a clinical and a management perspective. Finally, this paper could act as a route map for care pathways in both existing and future SAUs in Spain, and help guide the accreditation process of these facilities.

One weakness of this study is that the implementation of our indicators in participating hospitals may be complicated by their heterogeneity, e.g., organizational differences, such as the management of waiting lists, professional qualifications, difficulty in accessing new biological treatments, etc. As far as possible, therefore, the selected quality indicators focus more on direct patient care, which usually offers a certain degree of maneuverability, and less on the organizational logistics of each center.

ConclusionsThe Carabela project describes a minimum set of indicators and assessments, by which asthma centers and units can evaluate the quality of care they provide to patients with severe asthma and identify areas of improvement to optimize care for these patients. While this proposal is well founded the available evidence and on the opinion of a large number of Spanish experts, the performance of this approach needs to be tested in clinical practice.

Authors’ contributionAll authors (AC-L, JAM-E, JD-O,LP-LL, MB-A, MS, MP-C, FJ-A, JF) have made substantial contributions to the concept and design of the study, the acquisition of data, the interpretation of the results in virtual and face-to-face meetings, the writing of the article and its critical review, offering different intellectual contributions from their own particular multidisciplinary point of view. All have approved and revised the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Transparency statementThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other signatories, guarantees the accuracy, transparency and integrity of the data and information contained in the study; that no relevant information has been omitted; and that all discrepancies between authors have been properly resolved and described.

FundingThis project was sponsored and funded by the scientific societies involved: Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), Spanish Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (SEAIC), the Spanish Society of Quality of Care (SECA), and the Spanish Society of Health Managers (SEDISA), and managed by SEDISA through an unrestricted grant provided by AstraZeneca Spain.

Conflict of interestAC-L has received honoraria in the past 3 years for talks and meetings sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Orion Pharma, Gebro, Novartis, MSD and Boehringer Ingelheim. She has received travel expenses for attending conferences from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Chiesi, and Novartis, and has received funding/grants for research projects from several public agencies and non-profit foundations, in addition to AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. JAM-E, JD-O,LP-LL, MB-A, MS, MP-C, FJ-A, JF declare no conflicts of interest for this work.

We thank Dr. Beatriz Albuixech-Crespo, Dr. Maria Giovanna Ferrario and Dr. Blanca Piedrafita for their contribution as medical writers from the medical consulting firm Medical Statistics Consulting, and for their editorial support during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors thank the experts who participated in the Delphi questionnaire (Table A1) and all participants in the initial phases of the project for their collaboration.