To evaluate the access, development, and quality of consents forms for clinical practice within the Spanish Public Hospitals.

MethodA cross-sectional study was conducted in a two-stage process (January 2018–September 2021). In stage 1, A nationwide survey was undertaken across all public general hospitals (n=223) in the Spanish Healthcare System. In stage 2, Data was taken from the regional health services websites and Spanish regulations. Health Regional Departments were contacted to verify the accuracy of the findings. Data was analyzed using a descriptive and inferential statistics (frequencies, percentages, Chi-square & Fisher's exact tests).

ResultsThe response rate was 123 (55.16%) of Spanish Public Hospitals. The results revealed a range of hospital departments involved in the development of consent documents and the absence of a standardized approach to consent forms nationally. Consent audits are undertaken in 43.09% hospitals and translation of written consents into other languages is limited to a minority of hospitals (35.77%). The validation process of consent documentation is not in evidence in 13% of Spanish Hospitals. Regional Informed Consent Committees are not place in the majority (70.7%) of hospitals. Citizens can freely access to consent documents through the regional websites of Andalusia and Valencia only.

ConclusionVariability is found on access, development and quality of written consent across the Spanish Public Hospitals. This points to the need for a national informed consent strategy to establish policy, standards and an effective quality control system. National audits at regular intervals are necessary to improve the consistency and compliance of consent practice.

Evaluar la accesibilidad, la elaboración y la calidad de los formularios de consentimiento informado clínicos en los hospitales públicos de España.

MétodoEstudio observacional de corte transversal llevado a cabo en dos etapas (enero 2018-septiembre 2021). En la fase 1 se realizó una encuesta nacional en todos los hospitales generales públicos (n=223) del Sistema Sanitario de España. En la fase 2, los datos fueron extraídos de los portales web de salud autonómicos y de la legislación española. Se contactó con los organismos responsables (consejerías de salud regionales) en aras a verificar la fiabilidad de los hallazgos. Se utilizó estadística descriptiva e inferencial para el análisis de los datos (frecuencias, porcentajes, test de chi cuadrado y test de exacto de Fisher).

ResultadosLa tasa de respuesta fue de 123 hospitales públicos de España (55,16%). Los resultados revelaron una variedad de servicios hospitalarios involucrados en la elaboración de los documentos de consentimiento informado y la ausencia de un método de estandarización de los mismos a nivel nacional. Las auditorías de consentimiento se realizan en el 43,09% de los hospitales y la traducción de los consentimientos escritos a otros idiomas se circunscribe a una minoría de hospitales (35,77%). El proceso de validación de los consentimientos no se evidencia en el 13% de los hospitales españoles. Las comisiones autonómicas de consentimiento informado no están implementadas en la mayoría de los hospitales (70,7%). Los ciudadanos pueden acceder a los documentos de consentimiento informado a través de los portales web de salud regionales solo en Andalucía y en Valencia.

ConclusionesExiste variabilidad en la accesibilidad, la elaboración y la calidad de los documentos de consentimiento informado en los hospitales públicos de España. Esto sugiere la necesidad de desarrollar una estrategia nacional de consentimiento informado que establezca las directrices y los estándares para un control eficiente de la calidad. La realización de auditorías nacionales con regularidad contribuiría a mejorar la coherencia, la homogenización y el cumplimiento del consentimiento informado en la práctica clínica.

Informed consent in healthcare practice is considered a fundamental human right and is based on the ethical principle of autonomy and self-determination. It is understood to be an ongoing communication process in which a competent and well-informed patient makes a decision freely regarding a medical treatment, surgery, nursing care or whatever procedure is performed that involves his/her own health.1,2

A meaningful and genuine informed consent encourages patients’ participatory and deliberative decision-making in which the health information provided constitutes the cornerstone of this process.3 Consent documents for clinical practice, normally written in plain language, are used as a guide for the provision of verbal information. These are considered health education tools that can be consulted by patients as well as documentary evidence and a permanent record of the patient decision-making.4

The provision of high-quality health information has been demonstrated to enhance the patient experience and adherence to treatment; in addition improves communication between all stakeholders and contributes to an appropriate utilization of health care services.5,6 Despite the weight of evidence, many studies concluded that there is an immediate need to improve the process of obtaining patient consent within and across acute hospitals worldwide.7–13 The identified issues with consent process, include insufficient information regarding risks, complications and benefits,7,8 users consented less than 24h prior to surgery,9 deficiencies/inaccuracies in completion of the written consents9,10 as well as inappropriate readability level for the average citizen's comprehension.11–13

Across Healthcare Systems internationally, there is concern as to whether consent documents for clinical practice meet quality standards, i.e. whether they were subject to appropriate and accurate processes of development, validity, consistency, standardization and language translation.

The quality of the consent development process depends on its content.6,14 There is an expectation they will be underpinned by best evidence as well as ensuring the provision of sufficient and adequate information to enable citizens to make a knowledgeable and autonomous decision.2,6 A multidisciplinary committee or an Ethics Committee should oversee the validation and standardization of the written consent to ensure consistency. The validation process is based on three combined methods: external readers, readability indices and typographical features.6,14

Once a consent document is validated and standardized, this should be implemented and disseminated within the organization using the electronical medical records software. It is advisable to review and update the consent's content at regular intervals as this evolves continuously depending on the latest evidence and patient demands. Conducting regular audits also serves to assess the appropriateness of consent practice and the accuracy of documentation.8,9,14

In Spain, the organization of the Public Healthcare System is completely decentralized and devolved to seventeen Regional Health Services with total autonomy in the management of their system although the National Health Ministry does retain oversight of the quality of all regional Health Services, being responsible to ensure equitable implementation and patient health care rights across the country.15 In relation to patient consent, the Regional Health Services have freedom to organize the process of consenting and to develop their own regulations.

Previous research has not been conducted to explore if Spanish consent forms for clinical practice meet quality standards. The relevance of this research relies on identifying areas for improving quality in the Spanish Healthcare System.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the access, development and quality of written consents for clinical practice within the Spanish Public Hospitals.

MethodStudy design and populationA descriptive, observational cross-sectional study was undertaken. All Spanish Public General Hospitals registered within the National Catalogue of Hospitals16 (n=223) were included in this research. Exclusion criteria were Nursing Homes, Psychiatric Hospitals, Military and Prison Hospitals, and Private Hospitals and Clinics.

Data collectionThe present study was conducted in a two-stage process and data collection took place from January 2018 to September 2021. In stage 1, respondents were recruited through direct contact with each hospital executive management team to complete a specific survey (VERGILS questionnaire). In stage 2, data was extracted from the regional health services websites and relevant Spanish Health Ministry regulations to ascertain the features of regional informed consent committees. Health Regional Departments were also contacted to verify the accuracy and authenticity of the findings as clarifying or completing on any outstanding information.

Instruments and variablesThe VERGILS survey instrument was used and specifically designed to measure how Spanish Public Hospitals work in relation to consent forms. “VERGILS” Spanish acronym captures all of the structure, process and outcome criteria that relate to the logistics of obtaining written consents for clinical practice in Spanish hospitals as shown in Table 1:

VERGILS questionnaire.

| Variable | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| V | Validation | How is consent document validation undertaken in the Spanish Hospitals? |

| E | Elaboration | Which department is responsible for developing written consent forms within respective Hospital? |

| R | Review | How is quality control review process of consent forms within each Hospital |

| G | Guideline | What types of guidelines on good practice of informed consent are in use by healthcare professionals within hospitals? |

| I | Internationalization | Are the Spanish written consents translated into other languages? |

| L | Location | What is the location of the Spanish consent forms within Hospitals? |

| S | Standardization | Have consent forms been standardized at the regional level and are those available online? |

This instrument was subject to a process of validation prior to distribution to the Spanish Public Hospitals. Content validity was assessed through an expert panel to determine ease of survey completion, relevance clarity and representativeness of the questions. This expert panel consisted of 4 high skill healthcare professionals in the fields of Medicine, Ethics and Research. Once the VERGlLS questionnaire had been amended, a survey pilot study was undertaken to seek for respondents’ (n=10) feedback on the research tool and to identify potential challenges that might arise during the data collection. The final version of VERGILS was distributed as a self-administered or telephone-administered questionnaire.

Participant hospitals were categorized in accordance with the National Catalogue of Hospitals16 and the Spanish Health system review report.15 Spanish health care institutions are classified by the following features: the main purpose of hospital activities, location, healthcare resources & services available, ownership and organizational model. Thus, hospitals are classified as follows,

- •

National Hospital. National patient referral centre and the largest of the country dedicated to a specific medical specialty.

- •

Hospital network. A complex of hospitals which comprises between two to four health care institutions located within the same hospital site and in the capital city of a province. They are large's size hospitals at regional or provincial level.

- •

General or Acute Hospital. Hospital activity is focused on more than one specialty.

- •

District Hospital. A smaller hospital than regional or provincial centre which is located in urban areas out of the capital.

- •

High Resolution Hospital. Public self-managed General Hospitals recently built in Andalusia and Aragon regions as a new organizational strategy to improve efficiency.

- •

Public Foundation hospital. General hospitals with their own legal status, managed by a board supervised by the public health authorities.

- •

Network of Hospitals for Public Utilization. The Catalan Regional Health Service purchases hospital services from a network of general hospitals known as Xhup.20

- •

Integrated Health Organizations. A new model of care for complex chronic patients implemented in the Basque Health System. This consisted of merging a hospital and primary care structures under a single organization.

Hospitals are further categorized by size and associated bed capacity. The Spanish Health Ministry classification17 establishes six groups which was adapted according to the following criteria:

- •

<100 beds: very small hospital (Group A).

- •

100–199: small hospital (Group B).

- •

200–499: medium hospital (Group C).

- •

500–999: big hospital (Group D).

- •

>1000: very big hospital (Group E).

The existence, organization and nature of associated activity with regional informed consent committees was drawn from the regional health service websites.

Data analysisThe data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17 software. Descriptive Statistics were generated to illustrate frequencies and percentages in summary data. Inferential Statistics namely Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used to evaluate difference between groups. The level of statistical significance was set at p=0.05.

Ethical considerationsEach hospital executive management team provided authorization to participate in this study through the completion of a survey. Given the nature of this research and taking into account that the rest of data have been obtained from the public information available on the regional health services websites, no further permissions were required.

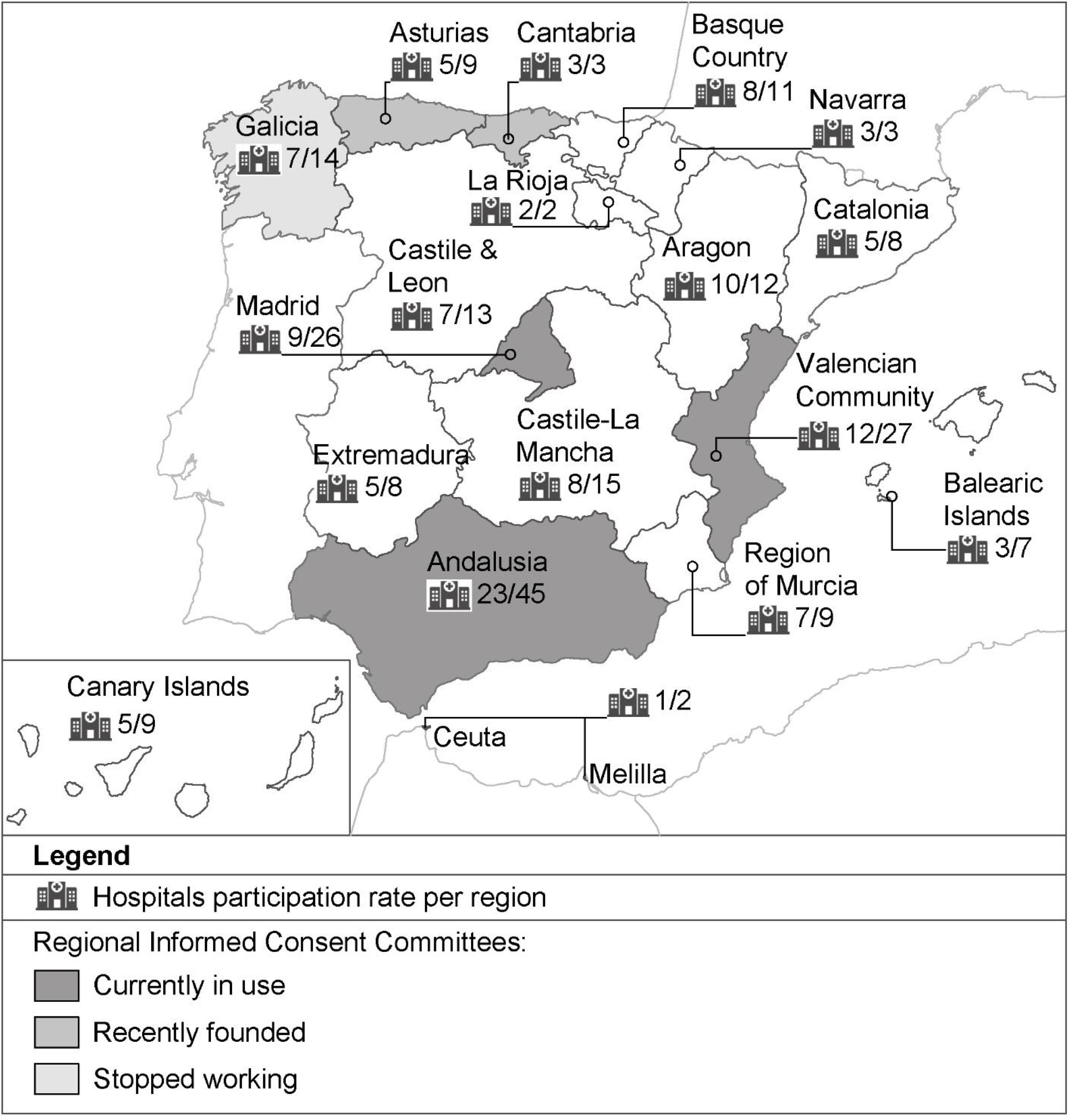

ResultsThe response rate was 55.16% (n=123) of hospitals from the target population (n=223) which represents a large proportion of Spanish Public Hospitals drawn from the seventeen regional health services. The response represented more than 50% Public Hospitals in each region and the regional spread as illustrated in Table 2.

Number and percentage of hospitals within region.

| Regional health services | Population of hospitals per region19 | Participants per region | Response rate per region | Inhabitants per region22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalucia | 45 | 23 | 51.11% | 8,384,408 |

| Aragon | 12 | 10 | 83.33% | 1,308,728 |

| Principality of Asturias | 9 | 5 | 55.56% | 1,028,244 |

| Canary Islands | 9 | 5 | 55.56% | 2,127,685 |

| Cantabria | 3 | 3 | 100% | 580,229 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 15 | 8 | 53.33% | 2,026,807 |

| Castile and León | 13 | 7 | 53.85% | 2,409,164 |

| Catalonia | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 7,600,065 |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 2 | 1 | 50% | 171,528 |

| Extremadura | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 1,072,873 |

| Galicia | 14 | 7 | 50% | 2,701,743 |

| Balearic Islands | 7 | 3 | 42.86% | 1,128,908 |

| La Rioja | 2 | 2 | 100% | 315,675 |

| Community of Madrid | 26 | 9 | 34.62% | 6,578,079 |

| Region of Murcia | 9 | 7 | 77.78% | 1,478,509 |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 3 | 3 | 100% | 647,554 |

| Basque Autonomous Community | 11 | 8 | 72.73% | 2,199,088 |

| Valencian Community | 27 | 12 | 44.44% | 4,963,703 |

| National total | 223 | 123 | 54.56% (average) | 46,722,980 |

The sample is described as per hospitals’ typology (Table 3) and hospitals’ size depending on the average bed number (Table 4).

Participant hospitals’ typology.

| Hospitals’ typology | n (%) |

|---|---|

| General hospitals | 60 (48.78%) |

| Hospitals network | 28 (22.76%) |

| High resolution hospitals | 13 (10.57%) |

| District hospitals | 11 (8.94%) |

| Network of Hospitals for Public Utilization (Xhup hospitals) | 5 (4.07%) |

| Integrated health organizations | 3 (2.44%) |

| Public foundation hospitals | 2 (1.63%) |

| National hospital | 1 (0.81%) |

In the majority of participating hospitals (69.92%) individual departments developed specific consent forms for clinical practice in line with the recommendations of scientific societies and considerable variability in the documents was noted. In a minority of surveyed hospitals, responsibility for this duty was undertaken by various departments, including admissions department (6.50%), quality & safety department (6.50%) or medical records (3.25%). In contrast, other hospitals (13.82%) had established Regional Informed Consent Committees to develop and implement standardized written consents within a defined geographic area.

Regarding the quality control of consent documents, the majority of hospitals (64.23%) reported that a process was in place for updating the content. Internal audits to check the accuracy and compliance of the informed consent process were undertaken by a significant number of hospitals (43.09%) whereas external audits were rarely undertaken (0.81%). The Regional Health Services with a higher rate of audits’ performance were Andalusia, Valencia, Catalonia and Extremadura whereas La Rioja and Navarre Health Systems rarely carried them out. High resolution centres were the most compliant hospitals (p=0.03). There was a significant relationship between audit performance and standardization of consent documents (p=0.04).

Consent forms were validated (81.30%) prior to its implementation either locally (49.60%), regionally (24.39%) or both (7.32%), although a significant proportion of hospitals were unable to report how the validation of consent documents was carried out (18.70%).

Access to written consents for clinical practice for health professionals was mainly through the local internal intranet system (76.42%), a private network platform intended for authorized hospital employees. Conversely, a large proportion of hospitals (23.58%) reported that some consent forms in use were not inserted in the Intranet platform yet, they were available in other locations instead, either a local computer platform, paper format or the combination of both.

Consent forms for clinical practice were largely available in Spanish in the majority of hospitals and in the co-official languages of the region such as Valencian, Catalan, Basque and Galician languages. Translation into another language occurred in 35.77% of hospitals and included the following: English (13%), Arabic (7.32%), French (5.69%), Polish (2.44%), German (1.63%) and Urdu (1.63%). Translation to Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Algerian, Moroccan and Norwegian languages were in evidence in a very small minority of hospitals (0.81%, respectively). There was also a higher prevalence of consent forms translated into other languages in Group C, D & E hospitals, therefore, those with a bed capacity between 200 and more than 1000 beds (p=0.01).

Regional informed consent committeesThe large majority of hospitals (70.7%) reported that there was no consent committee in their Regional Health Services. Six regional formal consent committees were detected in Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Valencia, Andalusia and Madrid for standardization and updating of consent forms. However, these committees were in different stages and circumstances as detailed in Fig. 1. The membership included an expert in Bioethics, in Health Law, a specialist physician from the field concerned and a doctor who represents the medical scientific society regarding the topic. Other healthcare professionals were not represented generally with one exception in Valencia which has a nurse. Of particular note was there was no patient or public representation on the committees.

The validation activity varied across committees, Andalusia reported the highest number, followed by Valencia and Madrid (Table 5). Valencia was also the only Committee that translated all written consents into English and Valencian languages. Citizens could freely download and access to all consent documents for clinical practice through the official regional websites in Andalusia and Valencia.

Features of regional informed consent committees.

| Regional informed consent committees which are running | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valencia | Andalusia | Madrid | |

| Year of creation | 2004 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Number of validated written consents | 362 | 512 | 7 |

| Validated written consents could be seen and downloaded on the regional website by citizens | Yes | Yes | No |

| Number of validated written consents translated into English on the regional website | 362 | 0 | 0 |

The integrity of the informed consent process is key to enabling patients to make informed decisions regarding their own health and health care. Written consents for clinical practice are tools to support the transmission of information to patients and provide evidence of the health decision-making process.3,5 The findings provide valuable information as to how the Spanish Health System works in regards to the access, development, validity, consistency, standardization and language translation of these tools of the consent process within public Hospitals.

This examination of the Spanish Health System confirms the range of hospital departments involved in the development of the consent documents and the absence of standardization at regional and national level. Of concern in the findings is validation of consent documents has not been completed in 18.70% Spanish hospitals. A recent study conducted by Mariscal-Crespo et al.11 concluded that the regional validation and standardization of these documents is associated with a higher readability level and its subsequent understanding by citizens. Given this fact, it urges to standardize the processes for the development and validation of consent forms for clinical practice. Although the existing regional consent committees are good examples of how these processes could be standardized and its potential benefits were confirmed through the results of this study, a national informed consent strategy would be advisable to support the creation of these bodies across the country as well as the development of policies, standards and guidelines for best practice in patient consent.

The findings clearly indicate that internal consent audits were only undertaken in less than half of participant hospitals. The results also suggest that management and organizational aspects related to Hospital typology may influence on audits’ performance and thus, the accuracy and the compliance of the written consents for clinical practice. Audits can foster improvements in consent practice, increasing the accuracy of the written consent, reducing the number of invalid consents and preventing errors in surgical procedures.8–10

Similarly, the variability of locations for the retrieval of written consents between and within Spanish hospitals (Intranet, local driver and paper formats) may hinder consent process for healthcare providers. Although there is a lack of robust empirical literature quantifying the most effective location for the consent documents within hospitals, previous studies highlighted that paper-based consents tend to have poor legibility and a higher frequency of missing or inaccurate information19 while an electronic consent system improves consistency of consent documentation, communication between stakeholders and healthcare coordination.20

Although consent forms for clinical practice are translated into co-official languages, there is a limited prevalence of written consents translated into others languages spoken in the country by minorities groups (i.e. migrants). This might be indicative of inequality in healthcare and could breach the principle of universality within the Spanish Health System. Many studies have shown that language barriers may lead to a failure in the validity of the consent-taking process21,22 and can impact quality of care.23,24 It is estimated that 10% of the users of the Spanish Health Service are non-citizens who speak different languages to Spanish but permanent residents in Spain18 who have the same entitlement to healthcare as Spaniards.25 Therefore the translation of consent documents into the most commonly spoken languages is essential to protect the patient's rights and ensuring equitable care to all citizens including vulnerable population groups.

The three Regional Informed Consent Committees (Valencia, Andalusia and Madrid) differed in terms of the activity, volume of standardized and validated consent forms, translation services, and committee membership. The Andalusian and Valencia Committees have all consent documents for clinical practice online and free to download with access available to all citizens. However, the large majority of regions across the country do not offer this service to their inhabitants, producing some ethical concerns. According to the core principles of equity and universality of the National Health System, all citizens should have the same healthcare services and resources regardless of their place of residence.15

There was no patient or public representation on these Committees. Evidence points to the benefit of including patients in the development and validity of consent documents in order to ensure patient comprehension and readability.26,27 The limited representation of other members of multidisciplinary team is a further limitation of the committee membership revealed in the findings. Surgical nurses for example perform a unique role in the consent process to oversee patient safety, ensuring that patient's fully understand the information provided by surgeons28–30 as well as the surgical checklist itself for the purpose of avoiding wrong-side events.9,10,30

LimitationsThe main limitation of this study was the access to the target hospitals. Although the National Catalogue Hospitals constituted a relevant source of information in relation to the contact details of each executive management team, this data was sometimes outdated, leading to the need to explore other options to collect data and set different strategies to get the highest feedback response rate. The complexity of access to and comparison of process in the hospitals was a challenge in undertaking a national multicentre survey, as well as the scarcity of information published on the regional health services websites.

ConclusionThis study gives insight into the performance of the Spanish Health System in relation to the tools for the consent process. The findings confirm the variability across the Spanish health services and point to the need for the implementation of a national informed consent strategy for the development, updating, quality control and standardization of consent forms for clinical practice. In this regard, increasing the representation of patients and other healthcare professionals in the current committees will enhance the opportunity to develop more patient-centred tools that are appropriate to enable citizens’ comprehension.

National audits at regular intervals will provide insight to organizational culture in relation to consent documentation and contribute to improving the consistency and compliance of the consent practice. Effective communication and cooperation between and across organizations is particularly crucial to identify issues for clinical practice and thus, the establishment of action plans and objectives ahead. Standardized written consents should be translated routinely into common languages spoken by foreign people resident in Spain. In this way, potential barriers to health equity are overcome & quality care assured to all citizens, regardless of their language, culture, religion or race.

Authors’ contributionsMorales-Valdivia, Estela and Mariscal-Crespo, María Isabel contributed to the design and implementation of the research. Morales-Valdivia, Estela carried out the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript with Camacho-Bejarano, Rafaela. Brady, Anne-Marie contributed to the paper critical review. All authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the final version.

Transparency declaration“The corresponding author, in the name of the rest of the signatories, declares that the data and information contained in the study are precise, transparent and honest; that no relevant information has been omitted; and that all the discrepancies among authors have been adequately resolved and described”.

FundingWithout funding.

Conflicts of interestsNone.

The authors would particularly like to thank all participant public hospitals of the Spanish Healthcare System for making this research possible.