Incident reporting systems (IRSs) are considered safety culture promoters. Nevertheless, they have not been contemplated to monitor professionals’ perception about patient safety related risks. This study aims to describe the characteristics and evolution of incident notifications reported between 2016 and 2019 in a high complexity reference hospital in Barcelona and explores the association between notifications’ characteristics and notifier's perception about incidents severity, probability of occurrence and risk. The main analysis unit was notifications reported. A descriptive analysis was performed and taxes by hospital activity were calculated. Odds ratios were obtained to study the association between the type of incident, the moment of incident, notifiers’ professional category, reported incident's severity, probability and incidents’ calculated risk. Through the study period, a total of 6379 notifications were reported, observing an annual increase of notifications until 2018. Falls (21.22%), Medical and procedures management (18.91%) and Medication incidents (15.49%) were the most frequently notified. Departments reporting the highest number of notifications were Emergency room and Obstetrics & Gynaecology. Incident type and notifiers’ characteristics were consistently included in the models constructed to assess risk perception. Pharmaceutics were the most frequent notifiers when considering the proportion of staff members. Notification patterns can inform professionals’ patient risk perception and increase awareness of professionals’ misconceptions regarding patient safety.

Los sistemas de notificación de incidentes promueven la cultura de la seguridad en los hospitales. Sin embargo, no se han considerado para conocer la percepción de los profesionales sobre los riesgos relacionados con la seguridad del paciente. Este estudio pretende describir las características y la evolución de las notificaciones de incidentes comunicadas entre 2016 y 2019 en un hospital de alta complejidad de Barcelona y explorar la asociación entre las características de las notificaciones y la percepción del notificador sobre la gravedad de los incidentes, la probabilidad de ocurrencia y el riesgo. La unidad de análisis principal fueron las notificaciones comunicadas. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo y se calcularon las tasas en relación con la actividad hospitalaria. Se obtuvieron las odds ratios para estudiar la asociación entre el tipo de incidente, el momento del incidente, la categoría profesional de los notificadores, la gravedad, probabilidad y riesgo calculado del incidente. A lo largo del periodo de estudio se registraron un total de 6.379 notificaciones, observándose un incremento anual de notificaciones hasta 2018. Las caídas (21,22%), los problemas en la gestión médica y de procedimientos (18,91%) y los incidentes de medicación (15,49%) fueron los más notificados. Los departamentos que reportaron el mayor número de notificaciones fueron urgencias y obstetricia y ginecología. El tipo de incidente y las características de los notificadores se incluyeron sistemáticamente en los modelos para evaluar la percepción del riesgo. Los farmacéuticos fueron la categoría profesional más notificadora considerando el número de profesionales en plantilla. Los patrones de notificación pueden informar sobre la percepción del riesgo de los pacientes por parte de los profesionales y ayudar a detectar creencias erróneas de los profesionales acerca de la seguridad de los pacientes.

Incident reporting systems (IRSs) are key in patient safety developing.1 The main goal of patient safety is considered to be the prevention of healthcare errors, reduce patient's safety risk and design measures to determine, report and correct the errors before they affect the patient.2

IRS aims to identify risks so actions can be implemented to minimize those risks. They allow continuous learning through the analysis of experiences that can compromise clinical safety. This gives the institutions the opportunity to design and implement preventive measures to ensure constant improvement of clinical practice. IRS are barely considered surveillance systems, as normally depend on surveillance awareness and honesty.2 Moreover, concerns have been raised about the difficult interpretation and comparison of results and their usefulness.3 However, they are thought to be operatively useful in identifying local hazards, can be used to identify protocol deviances through the collection of uncommon events and repetitive incidents, and have been considered a key part of a safety culture construction.1,4 Most groups claiming the IRS as safety culture promoter, relate to the fact that the more people notify, the more awareness there would be about patient safety and risks.5 Nevertheless, considering that IRS functioning depends on notifiers’ risk perception, to date, it has not been contemplated as a tool to monitor professionals’ perception about patient safety.

Recent reports and studies published with IRS data, refer mostly to the analysis of incidents related to specific health departments6–10 whereas some general country-level IRS analyses are available and based on hospital-level IRS data collection.11–13 Moreover, some studies have shown certain repetitive patterns of notification (e.g. doctors notifying incidents considered more severe and nurses notifying more events) in IRS data analysis.12,14–16

This study aims to describe the characteristics and evolution of incident notifications reported between 2016 and 2019 in a high complexity reference hospital in Barcelona and explores the association between notifications’ characteristics and notifier's perception about incidents severity, probability of occurrence and risk.

MethodologyStudy settingHospital Clínic is a high complexity reference hospital in Barcelona with a reference population of 540,000 inhabitants.17 It has 728 beds, and in 2019 reported 44,035 inpatient discharges, 142,823 Emergency room visits and 551,800 ambulatory visits. The hospital's activity is organized in divisions called institutes. Each institute is constituted by related departments – a description of these hospital sections has been described elsewhere.18 On another note, hospital human resources management is different between professional categories. There are three different shifts for nurses, auxiliary nurses, wardens and administrative staff – morning, noon and night, with 8h per shift. While medical professionals can work shifts of 8, 10, 16 or 24h depending on their professional category.

Patient safety IRSwas piloted in Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB) in 2014 and started its activity in October 2015. The implementation of the IRS led to the construction of multidisciplinary groups of delegates from each institute. These groups are called “Safety Nuclei” and they are responsible for analyzing and processing the notifications and for promoting and monitoring the implementation of improvement measures. Safety Nuclei are constituted by an interdisciplinary group of professionals and always include a pharmacist and a Preventive Medicine professional. This study includes notifications reported between 2016 and 2019, excluding the first months of implementation in 2015.

Data source and variablesThe main analysis unit was notifications reported to the HCB patient safety IRS. Notification details were collected on The Patient Safety Company® (TPSC) platform.19 TPSC platform is structured in different sections according to Hospital's institutes,12 hereinafter referred to as departments. Some platform variables were calculated and recategorized for the analysis.

Independent variablesThe platform variables chosen as independent variables were the department where the incident took place, contributing factors related to patient or professionals, people involved in the incident (patient or professionals), way of knowing (Experienced, when the notifier has had a first-hand experience of the incident and has been involved in it, Observed, Heard from Other), professional category (Doctor, Nurse, Assistant Nurse, Medical Residents, Pharmacist, Administrative Staff, Other) and type of incident according to the WHO taxonomy.20 The variable shift was calculated through the incident hour: 8.01–22.00h for the first and second shift (day shift) and 22.00–8.00 for the third shift (night shift). Holiday period was defined as a qualitative variable with two categories; holiday period (including the periods from December 23rd to January 7th, Easter holidays in each year and from the 1st of July till 31st of August) and non-holiday period (the rest of the year). Variables including department groups were regrouped in 4 categories: surgical, medical, medical-surgical (otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology and gynaecology) and Others (anatomopathology, biochemistry, genetics, analysis centre, pharmacy, radiology and nuclear medicine). Non-healthcare provider departments were excluded from the analysis.

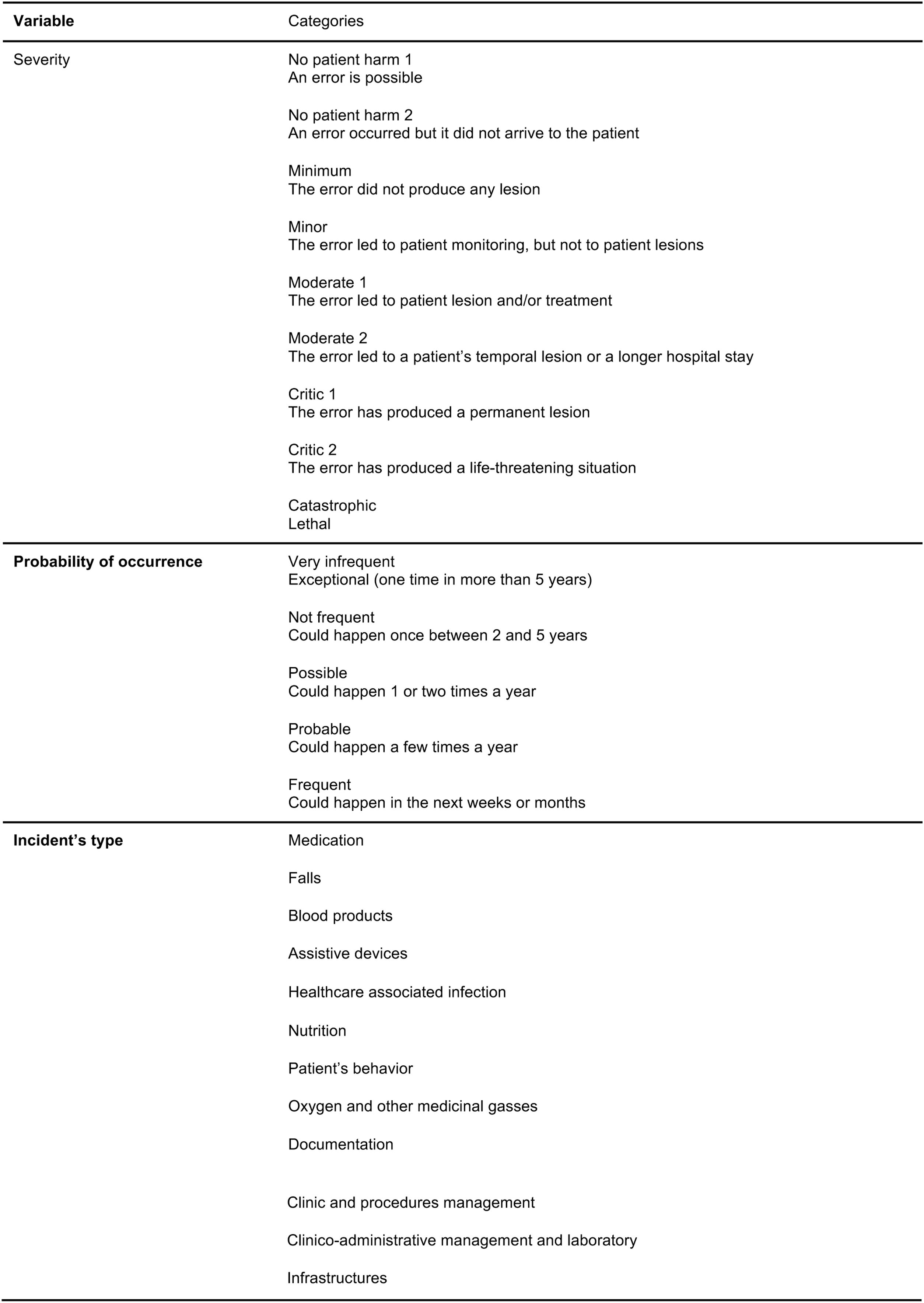

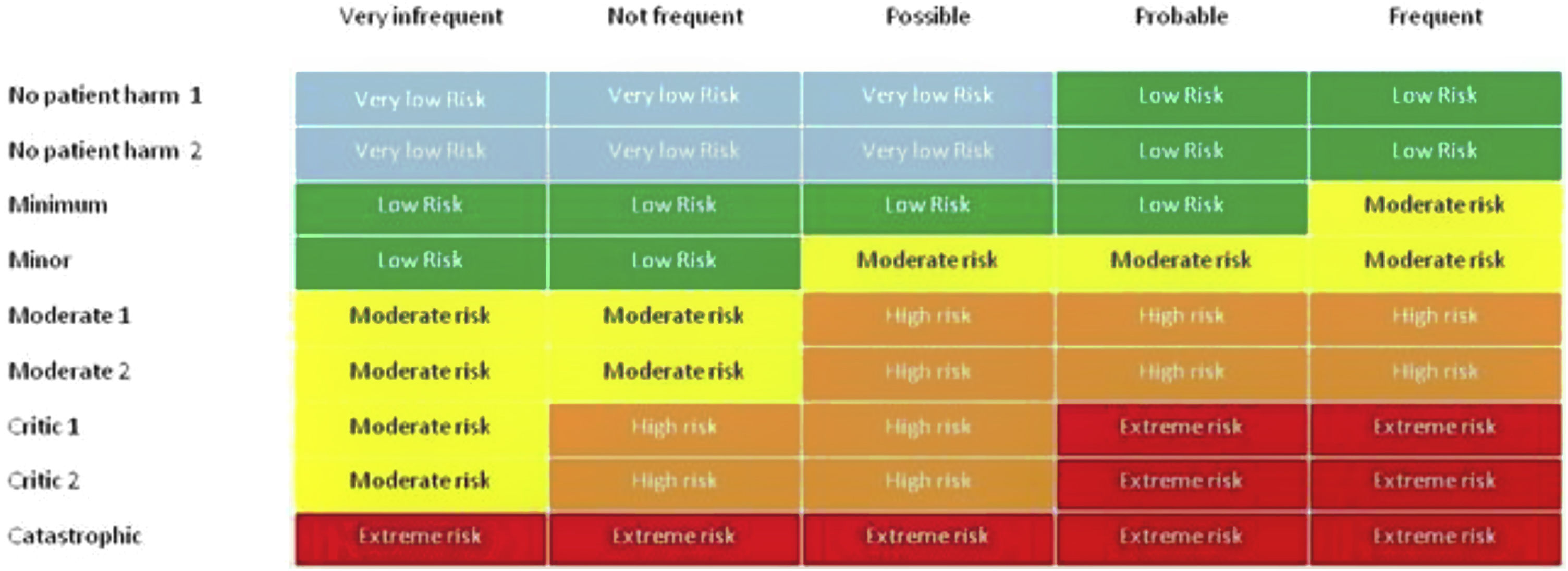

Dependent variableFig. 1 shows the characteristics of the platform variables included as dependent variables in this analysis. The risk assigned to each incident is calculated through the risk matrix presented on the platform (Fig. 2), which uses the variables “severity” and “probability of occurrence” for risk assignment (initially both reported by the notifier). The final risk assigned to each notification is the result of a twofold evaluation, the initial evaluation performed by the notifier based on the risk matrix and the subsequent healthcare contextualisation of the incident by the Safety Nuclei. Severity with initially 5 categories (no harm, minor harm, moderate, severe and extreme) was recoded into 3 categories for the analysis: No harm/minor harm, Moderate and Severe. Notifications classified as Extreme risk by the notifier are considered sentinel events. The probability of occurrence was also recoded into 3 categories: Infrequent, Occasional/Probable and Frequent.

Data analysisA descriptive analysis of the selected variables was performed. Incidents rate per hospital activity was calculated for each department using both the department's total discharges and total days of hospitalization. Taxes were calculated only considering inpatient care. Distribution of the number of notifications per variable was reported in absolute and relative terms and statistical comparison was performed through Chi square test considering all forms of healthcare. In order to compare the number of notifications per professional category, adjusted rates were calculated considering the number of workers for each professional category in 2019. Variables with more than 30% of missing values are excluded. Sentinel events detection was summarized narratively through the identification and classification by cause rout analysis processes.

The odds ratios (OR) with 95% of confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to study the association between the type of incident, the moment of incident (shift and holiday season), notifiers characteristics (department and professional category), and reported incident's severity, probability and incidents’ calculated risk. To calculate the OR, three ordinal logistic models were built following the Akaike Information Criterion21 to study the association between notification factors and reported probability of occurrence, severity and risk (hereinafter, model A, B and C respectively). All analyses were made with Stata 15.

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 6379 notifications were reported. Of these, 1170 (18.34%) were reported in 2016, 1637 (25.66%) in 2017, 1869 (29.30%) in 2018 and 1703 in 2019 (26.70%). Regarding the place where the notified incidents occurred, 3745 (58.71%) belonged to hospitalization episodes, 1212 (19.00%) to emergency episodes, 566 (8.87%) took place in the outpatient care, 492 (7.71%) in surgery, 361 (5.66%) belonged to non-assistance services and 3 (0.05%) were missing.

Considering the inpatient care activity, the Neuroscience and the Obstetrics & Gynaecology department had the highest rate of notifications per 1000 hospital discharges. This doubled other departments’ rates such as Orthopaedic Surgery & Rheumatology and Nephrology & Urology. The Obstetrics & Gynaecology department presented the highest notification rate per 1000 days of hospitalization and Cardiology & Cardiac surgery department the lowest. Some departments increased the number of notifications adjusted for activity during the study period (Gastroenterology & Metabolic Diseases) whereas others showed a decreasing trend (Cardiology & Cardiac surgery). The overall rates of notifications per 1000 hospital discharges and 1000 days of hospitalization increased from 2016 to 2018 and slightly decreased in 2019. Detailed rates are reported in Table 1.

Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges by department and year. IRS, Hospital Clínic 2016–2019.

| Institute | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology & cardiac surgery | |||||

| Number of notifications | 75 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 261 |

| Total discharges | 4536 | 4325 | 4502 | 4608 | 17971 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 16.5 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 14.5 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 28808 | 28463 | 28056 | 27284 | 112611 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Orthopaedic Surgery & Rheumatology | |||||

| Number of notifications | 46 | 78 | 54 | 49 | 227 |

| Total discharges | 5148 | 5236 | 5398 | 4970 | 20752 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 8.9 | 14.9 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.9 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 23812 | 23586 | 25413 | 23158 | 95969 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 1.9 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Obstetrics & Gynaecology | |||||

| Number of notifications | 167 | 231 | 367 | 253 | 1018 |

| Total discharges | 6927 | 6727 | 6636 | 6527 | 26817 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 24.1 | 34.3 | 55.3 | 38.8 | 38.0 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 24004 | 23717 | 23945 | 20698 | 92364 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 7.0 | 9.7 | 15.3 | 12.2 | 11.0 |

| Gastroenterology & Metabolic Diseases | |||||

| Number of notifications | 88 | 148 | 184 | 228 | 648 |

| Total discharges | 6189 | 6044 | 6049 | 6015 | 24297 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 14.2 | 24.5 | 30.4 | 37.9 | 26.7 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 39043 | 39343 | 37468 | 38113 | 153967 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 2.3 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 4.2 |

| Oncology & Haematology | |||||

| Number of notifications | 52 | 91 | 66 | 82 | 291 |

| Total discharges | 2219 | 2172 | 2234 | 2413 | 9038 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 23.4 | 41.9 | 29.5 | 34.0 | 32.2 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 22753 | 23481 | 23901 | 26230 | 96365 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 2.3 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.0 |

| Internal Medicine & Infectious Diseases | |||||

| Number of notifications | 69 | 114 | 104 | 103 | 390 |

| Total discharges | 2981 | 3374 | 3283 | 3682 | 13320 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 23.1 | 33.8 | 31.7 | 28.0 | 29.3 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 2786 | 30092 | 29386 | 33169 | 95433 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 24.8 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 4.1 |

| Neurosciences | |||||

| Number of notifications | 76 | 139 | 145 | 116 | 476 |

| Total discharges | 2912 | 2931 | 2916 | 2889 | 11648 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 26.1 | 47.4 | 49.7 | 40.2 | 40.9 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 30548 | 30884 | 31251 | 31611 | 124294 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 2.5 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| Nephrology & Urology | |||||

| Number of notifications | 73 | 63 | 50 | 76 | 262 |

| Total discharges | 3368 | 3404 | 3503 | 3816 | 14091 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 21.7 | 18.5 | 14.3 | 19.9 | 18.6 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 16838 | 16508 | 15760 | 16610 | 65716 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 4.0 |

| Respiratory Diseases | |||||

| Number of notifications | 30 | 65 | 51 | 26 | 172 |

| Total discharges | 1586 | 1533 | 1701 | 1766 | 6586 |

| Notifications per 1000 hospital discharges | 18.9 | 42.4 | 30.0 | 14.7 | 26.1 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 11928 | 11904 | 12472 | 12850 | 49154 |

| Notifications per 1000 days of hospitalization | 2.5 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 3.5 |

Departments reporting the highest number of notifications were Emergency room, with 1212, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, with 1130 notifications. While Emergency departments are prone to notify more frequent incidents, the Obstetrics & Gynaecology department has a larger proportion of severe notifications when comparing to the distribution of severity in other departments. Regarding the type of incident, Falls were the most common; a total of 1352 Falls were reported during the study period, which represents a 21.19% of notifications. However, Falls were classified mostly as occasional or infrequent incidents by professionals (55.92 and 12.57%, respectively). Second most common type of incident was related to Medical and procedures management (18.91%). In third place were those related to Medication incidents (15.49%).

Most frequent incidents are classified with low or moderate severity whereas less frequent notifications such as those related to blood products and oxygen are classified as high severity incidents. Nurses were the professionals who reported the highest number of notifications, in absolute value, reporting 60.44% of all notifications. Physicians were in second place, reporting 17.00% of incidents. However, considering the number of workers in each professional category, pharmacists were the professionals who notified more frequently, with 182.76 notifications per 100 workers in 2019, followed by nurses, with 52.42 notifications per 100 workers, assistant nurses with a rate of 51.63 and physicians, who reported 21.84 notifications per 100 workers in 2019. Administrative staff and other professionals had the lowest notification rates, with 3.08 and 2.78 notifications per 100 workers respectively. Administrative staff, doctors and medical residents notify a greater proportion of high severity incidents in comparison to other professionals. Pharmacists classified most of the reported incidents as frequent and minor severity. More than 75% of notifications referred to incidents occurred during the day shift. Notifications of night incidents were less frequent but more related to moderate and severe incidents. The most frequent way of knowing was the person's own experience (72.76%), followed by hearing from others (15.42%) and observed (11.82%). First-hand experienced incidents were more often classified as less severe and more frequent. Additionally, altogether, 28 sentinel events were notified (eight in 2016, five in 2017, twelve in 2018 and three in 2019).

Overall, contributor factors and people involved in the incident were more reported in those incidents classified as moderate or severe. The most frequent enabler factors reported as contributors to the incident were patients’ (36.65%) and professionals’ (35.49%). Incidents with a patient contributor were more often classified as moderate or severe in comparison to incidents with a professional enabler factor, classified mostly as no harm/minor harm. Patients were the most frequently involved in the incidents (69.69%) when the person involved was reported, further information in notification characteristics is shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Incident characteristics by probability. IRS, Hospital Clínic 2016–2019.

| Variables | Total | Probability | Missing values | p-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Infrequent | Occasional/Probable | Frequent | |||

| N (% of total) | ||||||

| Incident type | <0.000 | |||||

| Falls | 1352 | 425 (31.46) | 756 (55.92) | 170 (12.57) | 1 (0.07) | |

| Medical & Procedures Management | 1205 | 214 (17.76) | 468 (38.84) | 523 (43.40) | ||

| Medication | 987 | 238 (24.11) | 480 (48.63) | 269 (27.25) | ||

| Medical Devices | 741 | 202 (27.26) | 258 (34.82) | 279 (37.65) | 2 (0.27) | |

| Patient's Behaviour | 574 | 135 (23.52) | 210 (36.59) | 226 (39.37) | 3 (0.52) | |

| Infrastructures | 525 | 112 (21.33) | 135 (25.71) | 277 (52.76) | 1 (0.19) | |

| Analogic & Digital Documentation | 413 | 104 (25.18) | 190 (46) | 119 (28.81) | ||

| Clinical & Lab Management | 243 | 53 (21.81) | 115 (47.33) | 75 (30.86) | ||

| Nutrition | 138 | 38 (27.54) | 53 (38.41) | 47 (34.06) | ||

| Health-Care Associated Infection | 106 | 20 (18.87) | 43 (40.57) | 43 (40.57) | ||

| Blood Products | 72 | 24 (33.33) | 39 (54.17) | 9 (12.5) | ||

| Oxygen & Other gasses | 15 | 8 (53.33) | 3 (20) | 4 (26.67) | ||

| Non classified | 8 | 2 (25.00) | 1 (12.50) | 5 (62.50) | ||

| Department | <0.000 | |||||

| Cardiology & Cardiac Surgery | 267 | 102 (38.20) | 109 (40.82) | 52 (19.48) | 4 (1.50) | |

| Obstetrics & Gynaecology | 1130 | 237 (20.97) | 464 (41.06) | 429 (37.96) | ||

| Oncology & Haematology | 439 | 116 (26.42) | 206 (46.92) | 117 (26.65) | ||

| Gastroenterology & Metabolic Diseases | 695 | 213 (30.65) | 306 (44.03) | 174 (25.04) | 2 (0.29) | |

| Neurosciences | 498 | 105 (21.08) | 241 (48.39) | 152 (30.52) | ||

| Nephrology & Urology | 268 | 61 (22.85) | 128 (47.94) | 78 (29.21) | 1 (0.56) | |

| Internal Medicine & Infectious Diseases | 458 | 146 (31.88) | 234 (51.09) | 78 (17.03) | ||

| General Surgery & Anaesthesiology | 495 | 140 (28.28) | 190 (38.38) | 165 (33.33) | ||

| Orthopaedic Surgery & Rheumatology | 247 | 64 (25.91) | 108 (43.72) | 75 (30.36) | ||

| Respiratory Diseases | 178 | 65 (36.52) | 63 (35.39) | 49 (27.53) | 1 (0.56) | |

| Emergency department | 1212 | 224 (18.48) | 447 (36.88) | 541 (44.64) | ||

| Professional Category | <0.000 | |||||

| Doctor | 993 | 168 (16.92) | 401 (40.38) | 424 (42.7) | ||

| Nurse | 3856 | 1029 (26.69) | 1713 (44.42) | 1109 (28.76) | 5 (0.13) | |

| Assistant Nurse | 454 | 130 (28.63) | 167 (36.78) | 157 (34.58) | ||

| Medical Resident | 52 | 3 (5.77) | 15 (28.85) | 34 (65.38) | ||

| Pharmacist | 175 | 15 (8.57) | 118 (67.43) | 42 (24.00) | ||

| Administrative Staff | 64 | 17 (26.56) | 33 (51.56) | 14 (21.88) | ||

| Other | 246 | 71 (28.86) | 112 (45.53) | 63 (25.61) | ||

| Non-registered | 539 | 142 (26.35) | 192 (35.62) | 203 (37.66) | 2 (0.37) | |

| Shift | 0.008 | |||||

| Night | 1486 | 377 (25.37) | 680 (45.76) | 429 (28.87) | ||

| Day | 4893 | 1198 (24.48) | 2071 (42.33) | 1617 (33.05) | 7 (0.14) | |

| Contributing Factor Reported | 0.029 | |||||

| Yes | 4579 | 1104 (24.11) | 2028 (44.29) | 1442 (31.49) | 5 (0.11) | |

| No | 1800 | 471 (26.17) | 723 (40.17) | 604 (33.56) | 2 (0.11) | |

| Patient Was a Contributing Factor | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 1678 | 442 (26.34) | 829 (49.4) | 404 (24.08) | 3 (0.18) | |

| No | 4701 | 1133 (24.10) | 1922 (40.88) | 1642 (34.93) | 4 (0.09) | |

| Professionals Was a Contributing Factor | 0.294 | |||||

| Yes | 1625 | 380 (23.38) | 723 (44.49) | 522 (32.12) | ||

| No | 4754 | 1195 (25.17) | 2028 (42.72) | 1524 (32.1) | 7 (0.15) | |

| Patient Involved | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 4445 | 1125 (25.31) | 1971 (44.34) | 1345 (30.26) | 4 (0.09) | |

| No | 1934 | 452 (23.27) | 780 (40.33) | 701 (36. 25) | 1 (0.16) | |

| Professional Involved | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 1521 | 357 (23.47) | 623 (40.96) | 540 (35.50) | 1 (0.07) | |

| No | 4858 | 1218 (25.07) | 2128 (43.80) | 1506 (31.00) | 6 (0.12) | |

| Way of Knowing | <0.000 | |||||

| Experienced | 4186 | 956 (22.84) | 1680 (40.13) | 1545 (36.91) | 5 (0.12) | |

| Observed | 680 | 197 (28.97) | 357 (52.5) | 126 (18.53) | ||

| Heard from Other | 887 | 249 (28.07) | 483 (54.45) | 155 (17.47) | ||

| Not informed | 626 | 173 (27.64) | 231 (36.90) | 220 (35.14) | 2 (0.32) | |

aStatistical differences were calculated through the chi square test.

Incident characteristics by severity. IRS, Hospital Clínic 2016–2019.

| Variables | Total | Severity | Missing values | p-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No harm/Minor harm | Moderate | Severe | |||

| N (% of total) | ||||||

| Incident type | <0.000 | |||||

| Falls | 1352 | 607 (44.90) | 738 (54.59) | 7 (0.52) | ||

| Medical & Procedures Management | 1205 | 892 (74.02) | 287 (23.82) | 26 (2.16) | ||

| Medication | 987 | 783 (79.33) | 196 (19.86) | 8 (0.81) | ||

| Medical Devices | 741 | 523 (70.68) | 205 (27.67) | 12 (1.62) | 1 (0.13) | |

| Patient's Behaviour | 574 | 386 (67.25) | 177 (30.84) | 8 (1.39) | 3 (0.52) | |

| Infrastructures | 525 | 409 (77.90) | 98 (18.67) | 17 (3.24) | 1 (0.19) | |

| Analogic & Digital Documentation | 413 | 385 (93.22) | 26 (6.30) | 2 (0.48) | ||

| Clinical & Lab Management | 243 | 210 (86.42) | 30 (12.35) | 3 (1.23) | ||

| Nutrition | 138 | 123 (89.13) | 15 (10.87) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Health-Care Associated Infection | 106 | 73 (68.87) | 30 (2.83) | 3 (2.38) | ||

| Blood Products | 72 | 49 (68.06) | 19 (26.39) | 4 (5.56) | ||

| Oxygen & Other gasses | 15 | 10 (66.67) | 4 (26.67) | 1 (6.67) | ||

| Non classified | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Department | <0.000 | |||||

| Cardiology & Cardiac Surgery | 267 | 181 (67.79) | 78 (29.21) | 4 (1.50) | 4 (1.50) | |

| Obstetrics & Gynaecology | 1130 | 825 (73.01) | 267 (23.63) | 38 (3.36) | ||

| Oncology & Haematology | 439 | 305 (69.48) | 129 (29.38) | 5 (1.14) | ||

| Gastroenterology & Metabolic Diseases | 695 | 471 (67.77) | 217 (31.22) | 7 (1.01) | ||

| Neurosciences | 498 | 330 (66.27) | 166 (33.33) | 2 (0.40) | ||

| Nephrology & Urology | 267 | 190 (71.16) | 76 (28.46) | 1 (0.37) | 1 (0.56) | |

| Internal Medicine & Infectious Diseases | 458 | 297 (64.85) | 160 (34.93) | 1 (0.22) | ||

| General Surgery & Anaesthesiology | 495 | 365 (73.74) | 122 (24.65) | 1 (1.62) | ||

| Orthopaedic Surgery & Rheumatology | 247 | 148 (59.92) | 95 (38.46) | 4 (1.62) | ||

| Respiratory Diseases | 178 | 128 (71.91) | 44 (24.72) | 5 (2.81) | 1 (0.56) | |

| Emergency department | 1212 | 848 (69.97) | 353 (29.13) | 11 (0.91) | ||

| Professional Category | <0.001 | |||||

| Doctor | 993 | 653 (65.76) | 307 (30.92) | 33 (3.32) | ||

| Nurse | 3856 | 2622 (68.07) | 1196 (31.05) | 34 (0.88) | 4 (0.10) | 4 (0.10) |

| Assistant Nurse | 454 | 361 (79.52) | 91 (2.04) | 2 (0.44) | ||

| Medical Resident | 52 | 27 (51.92) | 23 (44.23) | 2 (3.85) | ||

| Pharmacists | 175 | 157 (89.71) | 17 (9.71) | 1 (0.57) | ||

| Administrative Staff | 64 | 54 (84.38) | 7 (10.94) | 3 (4.69) | ||

| Other | 246 | 180 (73.17) | 65 (26.42) | 1 (0.41) | ||

| Non-registered | 539 | 403 (74.77) | 120 (22.26) | 15 (2.78) | 1 (0.79) | |

| Shift | <0.000 | |||||

| Night | 1486 | 913 (61.44) | 544 (36.61) | 29 (1.95) | ||

| Day | 4893 | 3544 (72.43) | 1282 (26.20) | 62 (1.27) | 5 (0.10) | |

| Contributing Factor Reported | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 4579 | 3019 (65.93) | 1490 (32.54) | 67 (1.46) | 3 (0.07) | |

| No | 1800 | 1438 (79.89) | 336 (18.67) | 24 (1.33) | 2 (0.11) | |

| Patient Was a Contributing Factor | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 1678 | 868 (51.73) | 786 (46.84) | 22 (1.31) | 2 (0.12) | |

| No | 4701 | 3589 (76.35) | 1040 (22.12) | 69 (1.47) | 3 (0.06) | |

| Professionals Was a Contributing Factor | 0.029 | |||||

| Yes | 1625 | 1160 (71.38) | 434 (26.71) | 31 (1.91) | ||

| No | 4754 | 3297 (69.35) | 1392 (29.28) | 60 (1.26) | 5 (0.10) | |

| Patient Involved | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 4445 | 2870 (64.57) | 1516 (34.11) | 57 (1.28) | 2 (0.04) | |

| No | 1934 | 1587 (82.06) | 310 (16.03) | 34 (1.76) | 3 (0.16) | |

| Professional Involved | <0.000 | |||||

| Yes | 1521 | 1249 (82.12) | 242 (15.91) | 29 (1.91) | 1 (0.07) | |

| No | 4858 | 3208 (66.04) | 1584 (32.61) | 62 (1.28) | 4 (0.08) | |

| Way of Knowing | <0.000 | |||||

| Experienced | 4186 | 3040 (72.62) | 1093 (26.11) | 49 (1.17) | 4 (0.10) | |

| Observed | 680 | 387 (56.91) | 283 (41.62) | 10 (1.47) | ||

| Heard from Other | 887 | 561 (63.25) | 309 (34.84) | 17 (1.92) | ||

| Not informed | 626 | 469 (74.92) | 141 (22.52) | 15 (2.40) | 1 (0.16) | |

aStatistical differences were calculated through chi square test.

In the models’ construction, the inclusion of the moment of incident varied depending on the dependent variable assessed. On the one hand, none of the models included the holiday period as a significant variable through the Akaike Information Criterion. However, model B included the variable shift. Conversely, incident type and notifier characteristics (department and professional category) were consistently included in the three models.

In model A, Medical and procedures management incidents were consistently and significantly categorized as frequent (OR 2.21 [95% IC 1.30–3.76]) as well as Infrastructure incidents (OR 2.14 [95% IC 1.23–3.73]). In model B, where Analogic and digital documentation incidents was the reference category, all other incident types were significantly associated with higher reported severity notifications, However, Falls (OR 25.28 [95% IC 15.93–40.11]) and Oxygen & other gasses incidents (OR 12.19 [95% IC 3.62–41.07]) were the type of incidents more strongly associated with higher reported severity. Overall, in the adjusted model C, Falls (OR 13.79 [95% IC 7.47–25.46]), Patient Behaviour (OR 3.08 [95% IC 1.72–5.53]), Healthcare Associated Infection (OR 3.94 [95% IC 1.66–9.38]) and Medical and procedures management (OR 2.88 [95% IC 1.65–5.04]) were the incident types with more Risk OR.

Regarding notifiers characteristics, pharmacists and medical residents were the professional categories significantly associated with notifications categorized as frequent (OR 4.99 [95% IC 2.24–11.12] and 5.66 [95% IC 1.53–20.93] respectively). Whereas this tendency was maintained for severity in medical residents, pharmacists were the professionals that reported the mildest incidents (taken as a reference category in Model B). On the other hand, being a doctor or a nurse was significantly associated with the reporting of more severe incidents (OR 4.16 [95% IC 2.44–7.09] and 2.00 [95% 1.19–3.35]), respectively. When studying the association of areas of specialization, our data showed that medical and medical-surgical departments tend to report incidents that are considered more frequent in comparison to Surgery departments (non-statistically significant), whereas medical and surgical departments tend to report more severe notifications in comparison to medical-surgical departments. Further OR and 95% CI of the three models can be observed in Table 4

Probability, severity and risk by reported incident characteristics.

| Model A: Reported Probability | Model B: Reported Severity | Model C: Calculated Risk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | [OR 95% Conf. Interval] | Odds Ratio | [OR 95% Conf. Interval] | Odds Ratio | [OR 95% Conf. Interval] | ||||

| Shift | |||||||||

| Night | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Day | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Type of Incident | |||||||||

| Blood products | 1 | 7.81 | 3.93 | 15.50 | 1.00 | ||||

| Falls | 1.189 | 0.707 | 1.999 | 25.28 | 15.93 | 40.11 | 13.79 | 7.47 | 25.46 |

| Patient behaviour | 1.668 | 0.968 | 2.872 | 9.63 | 5.95 | 15.60 | 3.08 | 1.72 | 5.53 |

| Medical devices | 1.340 | 0.786 | 2.284 | 7.72 | 4.80 | 12.43 | 2.23 | 1.27 | 3.93 |

| Analogic & digital documentation | 1.375 | 0.788 | 2.399 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.58 | 1.82 | ||

| Clinical & Lab Management | 1.628 | 0.896 | 2.959 | 2.49 | 1.39 | 4.44 | 1.95 | 1.03 | 3.68 |

| Medical & procedures management | 2.211 | 1.301 | 3.757 | 5.14 | 3.23 | 8.17 | 2.88 | 1.65 | 5.04 |

| Health-care associated infection | 1.913 | 0.943 | 3.881 | 9.06 | 4.87 | 16.88 | 3.94 | 1.66 | 9.38 |

| Infrastructures | 2.138 | 1.226 | 3.730 | 4.66 | 2.83 | 7.66 | 2.42 | 1.35 | 4.34 |

| Medication | 1.352 | 0.796 | 2.296 | 5.28 | 3.28 | 8.50 | 1.48 | 0.85 | 2.57 |

| Nutrition | 1.292 | 0.674 | 2.475 | 2.69 | 1.29 | 5.62 | 2.30 | 1.12 | 4.70 |

| Oxygen & other gasses | 0.454 | 0.136 | 1.513 | 12.19 | 3.62 | 41.07 | 2.43 | 0.49 | 12.03 |

| Medical or Surgical Departments | |||||||||

| Surgery | 1.00 | 1.99 | 1.26 | 3.14 | 1.91 | 1.13 | 3.24 | ||

| Medical | 1.171 | 1.000 | 1.372 | 1.71 | 1.11 | 2.66 | 1.59 | 0.97 | 2.61 |

| Medical-Surgical Departments | 0.778 | 0.520 | 1.166 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Others | 1.247 | 0.984 | 1.580 | 2.07 | 1.29 | 3.31 | 1.97 | 1.14 | 3.40 |

| Professional category | |||||||||

| Administrative stuff | 1 | 1.78 | 0.73 | 4.32 | 1.00 | ||||

| Doctors | 1.827 | 0.996 | 3.353 | 4.16 | 2.44 | 7.09 | 3.09 | 1.65 | 5.79 |

| Nurses | 1.219 | 0.676 | 2.198 | 2.00 | 1.19 | 3.35 | 2.03 | 1.11 | 3.70 |

| Pharmacists | 4.991 | 2.240 | 11.120 | 1.00 | 1.51 | 0.75 | 3.03 | ||

| Assistant Nurse | 1.129 | 0.602 | 2.119 | 1.24 | 0.69 | 2.22 | 1.42 | 0.74 | 2.74 |

| Medical Residents | 5.659 | 1.530 | 20.931 | 6.82 | 3.19 | 14.57 | 9.65 | 2.07 | 45.05 |

| Others | 0.981 | 0.521 | 1.843 | 1.76 | 0.99 | 3.13 | 2.16 | 1.10 | 4.25 |

Since the implementation of the IRS system in the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, the overall notification rate increased during the first years of implementation, stabilizing during the last year analyzed. Nurses were the professional category that notified the most, followed by doctors. Falls were the most frequent incident notified, followed by Medical and procedures management and Medication notifications. While the decrease in the number of notifications in 2019 can be interpreted as a regression towards the mean (or stabilization of the tendency), the great number of Falls notifications may be related to the previous existence of a Falls notification system in our hospital. Moreover, it might be associated with how easier it could be for professionals to notify incidents they attribute to be related to a patient's action or environmental conditions. This system was led by nurses and implemented before the IRS and might have contributed to the hospital's safety culture. The same reasoning applies to the great number of notifications in the Obstetrics & Gynaecology department and the Emergency room, two departments that were pioneers in safety culture in the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona.

As in previous evidence,12 Falls were the incident most frequently reported, it was one of the incidents perceived as less frequent. The opposite notification pattern can be observed in Health-care Associated Infections. These are perceived as being frequent and minor, however, they were the third least frequently notified and a recognized cause of healthcare associated deaths.22 As such, the notifier's perception did not reflect neither the healthcare professionals’ notification behaviour nor patient safety risks. Nevertheless, this provides us an overview of what the professional perception about patient risk is and this could be used as a tool to improve notification behaviours and safety culture.

Globally, incidents perceived as less severe (no harm or minor harm) were more notified, and in line with previous research, incidents were more frequently reported when they rely on the professional's direct experience.14 Over the four years of the period study, most notifications of incidents considered as mild are notified by nurses, whereas notifications of the severe ones are done both by nurses and doctors. This is consistent with previous literature.12,14–16 However, physicians have been identified as the most notifying professionals in some specific IRS7 and when adjusting by the total number of hours worked.3

Conversely, pharmacists consistently tend to notify incidents perceived as minor and more frequent. These differences in notification patterns could depend on context, time spent with the patient,23 patient safety awareness, safety cultural background and type of healthcare activity. Although different patterns between pharmacists, doctors and nurses are probably related to job characteristics (relationship with the patient, level of responsibility), it has been shown that professionals tend to notify incidents that potentially have more direct and quick solutions, such as Falls or Medication.14 Considering these dimensions in further analysis could help characterize patient risk misconceptions among different professional groups and design interventions that could be adapted to the group safety culture.

IRSs have been recently overlooked as a surveillance tool and as a proxy of patient safety due to the dependence on notifiers’ perspective. Nevertheless, recognizing the different notification patterns and professional risk perceptions, IRS information can be analyzed in conjunction with mortality, morbidity and work-related data to build interventions in order to improve safety culture.24 Moreover, personalized feedback on IRS information reporting, could be used as a patient safety learning platform.25 The identification of notification gaps (such as the lack of notifications of severe healthcare related infections) and notification reporting patterns (qualify Falls as not as frequent) in professional groups or departments can be used as a tool to work over patient risks, safety and developed safety culture in a more contextualized way.

This study shows notification department's activity and offers the possibility of analyzing departments and professional's notifying patterns, allowing contextualized comparison of safety culture. We also provide a more in-depth analysis about notifiers perception by using a calculated risk variable. Nevertheless, some departments, such as Surgery, notify by department-specific IRS which has led to an underrepresentation of this group of notifiers. As this study does not aim to analyze incidents, but notifications, no proxy patient safety indicator was calculated, and no direct measure of patient safety can be obtained through this study, however, this data provides a framework for future analysis and provides indirect quantitative data on notifiers risk perception. Even though we considered the potential relevance of shifts or holidays in our models, more detailed analysis considering professional hours worked or time should be performed in order to evaluate how this can evaluate the notification rate. As Tricarico et al. referred, changes in the notification rate overtime or per working hour could help contextualize safety risk perceptions or notification patterns3 which might imply continuous improvement of IRS reporting.26

In conclusion, IRS data analysis can provide sectorize information about notification patterns that show notifiers’ patient risk perception. Our results show how incidents perceived as minor and frequent are less frequently notified while incidents perceived as less frequent are the most frequently notified. Moreover, the professional category and department play a role in notification culture.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest in this article.