Adolescence is characterized by ongoing neurocognitive maturation, particularly in regions that support social–emotional processing and cognitive control. Despite extensive research on emotion regulation, the developmental trajectories of critical neural networks—such as the salience network and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)—remain incompletely understood.

MethodsWe prospectively enrolled 30 adolescents (12–18 years), 35 early adults (19–24 years), and 35 adults (25–34 years). While undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging, participants performed an emotional discrimination task on facial expressions. The imaging data were analyzed to assess the neural activity across the emotional conditions, and a generalized psychophysiological interaction approach was applied to examine salience network connectivity.

ResultsAdolescents exhibited lower behavioral performance than adults. Regarding brain activation, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and bilateral insula—key components of the salience network—seemingly differentiated adolescents from early adults and adults. In contrast, DLPFC activity distinguished adults from the two younger groups. Functional connectivity analyses revealed that adolescents either over-sustained or under-recruited dACC–insula connectivity during emotional transitions, correlating with poorer behavioral performance.

ConclusionThese findings underscore distinct developmental trajectories for the salience network and the DLPFC, with adolescents showing heightened vulnerability in social–emotional processing and cognitive control.

Adolescence is widely recognized as a developmental period of profound psychosocial, cognitive, and neurobiological changes that bridge childhood and adulthood (Arain et al., 2013; Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). These transformations encompass advanced intellectual growth, substantial hormonal shifts, and considerable maturation of brain structures, which collectively manifests in notable progress in behavioral and cognitive capabilities (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). Among the brain regions that undergo significant development, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a central role in higher-order cognitive functions, such as decision-making, inhibitory control, and social understanding (Dumontheil, 2016). The development of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is a prolonged process that extends into early adulthood, and plays a crucial role in the maturation of cognitive and socioemotional functions (Delevich et al., 2018; Eslinger & Tranel, 2005; Popplau et al., 2024). Given the crucial importance of PFC development for cognitive and socioemotional maturation, it is also a period of vulnerability (Popplau et al., 2024).

Within a social context, the ability to recognize, interpret, and respond to facial expressions is fundamental for successful interpersonal interactions (Herba & Phillips, 2004; Kilford et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2007). Neuroimaging research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has consistently highlighted the role of frontal and cingulate circuits in evaluating facial emotion (Fusar-Poli et al., 2009; Kesler-West et al., 2001; Richey et al., 2022). Studies on emotional regulation and cognitive control have mainly reported top–down regulatory processes that involved the PFC and subcortical structures (Arnsten & Rubia, 2012; Robbins & Arnsten, 2009). However, some findings suggest that functional connectivity varies depending on situational demands and task requirements (Ochsner et al., 2009; Underwood et al., 2021).

In the neural architecture of social–emotional processing, the salience network (SN), which comprises the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and insular cortex, constitutes a crucial component (Menon & Uddin, 2010; Seeley, 2019). This network is instrumental in identifying behaviorally relevant internal or external stimuli, subsequently initiating adaptive cognitive responses (Ham et al., 2013; Rosen et al., 2018; Seeley, 2019). Abnormal activity or disrupted connectivity within the SN has been linked to various psychiatric and behavioral maladaptations (Huang et al., 2022; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2023). In adolescence, the anterior cingulate cortex—an integral hub of the SN—often shows less mature functional engagement in both incidental and directed emotion-processing tasks relative to adulthood (Passarotti et al., 2009). For instance, adolescents exhibiting weaker SN coherence tend to report more severe depressive symptoms and negative self-referential thought patterns (Schwartz et al., 2019). Conversely, early-life adversity such as abuse or neglect may increase the functional connectivity within the SN, suggesting either a compensatory or a maladaptive hyper-engagement of salience-related pathways (Todeva-Radneva et al., 2023). Given these findings, the SN emerges as a critical target for understanding how social and emotional factors shape brain maturation. While many studies have examined neural differences between adolescents and adults in the context of emotional regulation (McRae et al., 2012; Pozzi et al., 2021; Stephanou et al., 2016), relatively few have focused on age-specific differences within the SN and the frontal lobe.

To address these gaps, the present study aimed to examine age-dependent changes in behavioral performance, neural activation, and functional connectivity within the salience network (SN) during emotional facial recognition. Specifically, we focused on how emotional transitions engage the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), insula, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) across three age groups—adolescents, early adults, and adults. By employing an emotional discrimination task and generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analyses (see Fig. 1), we hypothesized that adolescents would exhibit distinct neural and behavioral responses compared with adult groups. We further expected that functional connectivity within the SN would demonstrate unique patterns in adolescence, and that the role of the DLPFC would vary by age, reflecting ongoing maturation of cognitive and emotional regulation. By delineating these developmental trajectories, the current study seeks to provide new insights into how maturing neural circuits facilitate the transition from adolescent to adult social and emotional functioning.

Measurement of brain activity and functional connectivity during an emotional discrimination task. The behavioral and fMRI data from participants aged 12–33 years were collected during emotional discrimination tasks. The imaging parameter estimates for each condition were generated according to the emotional expression and status of the stimuli. Subsequently, the parameters for the four emotional and group conditions were considered in the flexible factorial model. To investigate the relationship between the emotional context and the salience network, the PPI parameters were extracted and analyzed from the cluster that showed connectivity with the dACC in each condition. AA, angry face followed by angry face; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AH, angry face followed by happy face; HA, happy face followed by angry face; HH, happy face followed by happy face; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; PPI, psychophysiological interaction; ROI, region of interest.

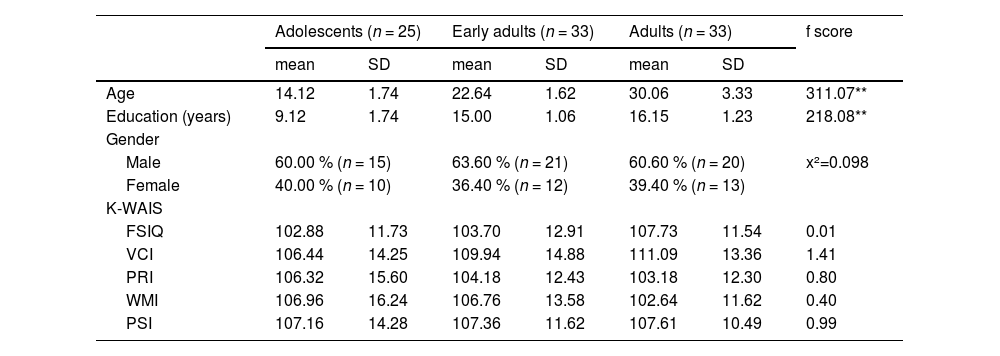

Thirty adolescents (12–18 years of age), 35 early adults (19–24 years of age), and 35 adults (25–34 years of age) participated in this study. Every participant underwent a comprehensive evaluation known as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, which was administered by a physician. The objective of this evaluation was to ascertain the individuals who presently possess a mental diagnosis. The exclusion criteria encompassed those with a history or current presence of significant medical, neurological, or psychological conditions. Two adolescents with depressive condition were eliminated, along with one adult. Additionally, the data from three adolescents and two early adults were excluded due to significant head motion detected during imaging preprocessing. Consequently, the data from 25 adolescents (10 females, 14.12 ± 1.74 years), 33 early adults (12 females, 22.64 ± 1.62 years), and 33 adults (13 females, 30.06 ± 3.33 years) were considered in this study. All participants had a normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were right-handed assessed by the Edinburgh handedness inventory (Oldfield, 1971). In this study, the gender of participants almost evenly distributed across ages in each group (χ2(2) = 0.098; p = .95) (Table 1). They had normal intelligence, and there were no group differences statistically in full scale intelligence (FSIQ) (F(2, 88) = 0.01, p = .99), and its four subscales, verbal comprehension index (VCI) (F(2, 88) = 1.41, p = .25), perceptual reasoning index (PRI) (F(2, 88) = 0.80, p = .45), working memory index (WMI) (F(2, 88) = 0.40, p = .67), and processing speed index (PSI) (F(2, 88) = 0.99, p = .38) (Table 1). The Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital accepted this study, and all experiments were conducted in compliance with the applicable standards and regulations. Adults, early adults and both the adolescents and their parents submitted written consent which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital before participation in this study.

Demographic characteristics of groups.

*p < .05, **p < .001.

The male and female emotional faces were chosen from the Korean Facial Expressions of Emotion (KOFEE) database (Lee et al., 2014). Each face image contained two emotional expressions (happy and angry) (Fig. 2a). The trials comprised four stimuli that were determined by the emotional valence and emotional status of the face. Thus, there were four conditions: happy faces followed by happy faces (HH), angry faces followed by happy faces (AH), angry faces followed by angry faces (AA), and happy faces followed by angry faces (HA). In the previous study, this experimental paradigm was devised to examine the cognitive regulation of emotional faces (Chun et al., 2017). The experimental sequence was divided into two sessions and executed using a rapid event-related design. Each trial lasted for 1500 milliseconds, and the interval between trials ranged from 500 to 4500 milliseconds using Optseq2 (surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/optseq/). Every session commenced with six preliminary trials and comprised a total of 160 occurrences, which were evenly distributed among four categories: 40 trials of HH, 40 trials of AH, 40 trials of AA, and 40 trials of HA. The participants were asked to press a button with their left or right index finger in response to a positive or negative produced by the facial expression, respectively, regardless of the picture’s location. To sustain the attention of the participants, the emotional stimuli for each trial were exhibited either to the left or right side of the crosshair, which was positioned at the center of the gray background. The position of emotional discrimination for facial expression was counterbalanced.

Behavioral performance: error rates and reaction times across different groups and emotional conditions. (a) Schematic representation of the experimental conditions. Each condition is labeled according to the facial emotional expression and the emotional status. (b) Error rates across different groups and conditions. The error rate data demonstrated significant group differences. (c) Reaction times (RTs) across different groups and conditions. Significant main effects were observed for emotional expression and status. (d) Correlation between RT and perceptual reasoning index (PRI), a subscale of the full-scale intelligence quotient. AA, angry face followed by angry face; AH, angry face followed by happy face; HA, happy face followed by angry face; HH, happy face followed by happy face.

Functional and structural MRI data were acquired using a 3T MRI system (Siemens, MAGNETOM Verio, Erlangen, Germany) with a 16-channel receiver head coil. The functional MRI data were obtained using a T2*-weighted gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, image matrix = 124 × 124, field of view (FOV) = 220 mm, flip angle = 90°) with an in-plane resolution of 1.719 mm × 1.719 mm (31 slices of 3.5 mm thickness and no gaps). Each session started with a 12-s dummy scan with six practice trials and obtained 226 vol with a total scan time of 7 min 32 s. Structural images with a resolution of 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm were acquired using a 3D T1-weighted gradient echo sequence (170 slices, TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.22 ms, image matrix = 256 × 256, FOV=256 mm, flip angle = 9°).

Behavioral data analysisThe behavioral data were examined based on the emotional expression (happy, angry) of the face, emotional status (repetition, transition), and age-related group (adolescents, early adults, and adults). The behavioral performances, as evaluated by error rate and reaction time, were investigated using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the main effects and their interactions using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 28.0; IBM, Armonk, NY). Subsequently Benjamini-Hochberg corrected t-tests for post hoc analyses were performed to test the significance between the different groups. In addition, we investigated the correlation between reaction time and PRI in each group.

Image data preprocessing and analysisImage preprocessing and General Linear Model (GLM) analysis were performed with Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12; Wellcome Center for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, UK). After discarding the first six images from the dummy scan at each session, the remaining 220 images were used for further preprocessing. The time differences by slice acquisition of interleaved sequence were corrected in the slice timing step, and the artifact created by head motion was corrected in the realignment step. The corrected images were coregistered on the T1-weighted image of the same participant, and the T1-weighted images were normalized to the standard T1 template. Spatial smoothing of functional data was applied using 8-mm full-width at half-maximum kernel.

Experimental trials were modeled separately using a canonical hemodynamic response function for individual data. Multiple linear regression, as implemented in SPM12 using a least-squares approach, was used to obtain the parameter estimates. These estimates were then analyzed by testing specific contrasts using the participant as a random factor. According to the emotional valence and status of the stimuli, all trials were classified as HH, AH, AA, and HA conditions. Images of the parameter estimates for each condition were created in the 1st level analysis, during which individual realignment parameters were entered as six regressors to control for movement-related variance. For the secondary analysis, the parameters for the four conditions, which were estimated in the primary, and group conditions were considered in the flexible factorial model. The results were measured with group differences in four conditions (HH, AH, AA, and HA). Significant results of group differences were determined by family-wise error (FEW) corrected p values of <0.001 were considered the region activated >100 voxels preferentially. In addition, significant results of the emotional condition within the group were determined by false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p values of <0.001 and were adopted in the region that activated >100 voxels.

The group differences of target regions were investigated using the Benjamini-Hochberg method on the predefined regions of interest (ROIs). These ROIs were identified as significant clusters within the salience network, including the combined bilateral dACC [−8, 14, 40; 6, 10, 38] and bilateral insula [−34, 18, 4; 36, 16, 6], and within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) [−44, 42, 10] related to crucial neurodevelopment. The % BOLD signal changes in the ROIs were extracted using MarsBaR version 0.41 (http://marsbar.sourceforge.net) in the AH condition, which was identified interaction in behavioral data analysis. The extracted values in ROI were used in a 2 (emotional valence: happy, angry) by 2 (emotional status: repetition, transition) by 3 (age group: adolescents, early adults, and adults) repeated measures ANOVA using IBM SPSS 28.0.

We conducted exploratory generalized PPI functional connectivity analyses (23) to investigate the SN involved in detecting emotional facial transitions. Generalized PPI regression analyses were conducted using the CONN toolbox (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn/) (24) with the dACC region as our region of interest (ROI). Statistically significant changes were identified using corrected p-values of <0.001 for family-wise error with >100 voxels activated. To investigate changes in the functional connectivity in the dACC depending on the group, we extracted PPI parameters from the cluster that exhibited significant connectivity with the dACC in each condition. Subsequently, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected t-tests for post hoc analyses were performed to test the significance between the different groups. We also used Pearson's correlation analysis to evaluate the relationship between PPI parameters and reaction time for emotional transition within each group. Moreover, the statistical difference in Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the groups was determined using Fisher's r-to-z transformation.

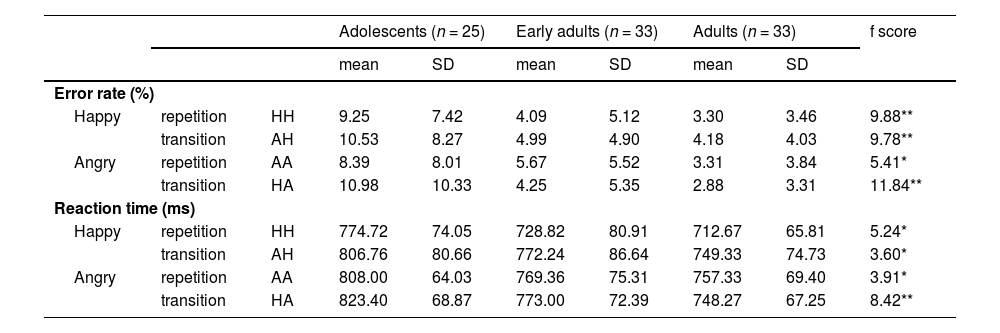

ResultsBehavioral performanceAs shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2b, there was a significant main effect of Group on error rate, F(2, 88) = 12.05, p < .001, η² = 0.22. Benjamini–Hochberg–corrected post hoc tests indicated that adolescent participants made significantly more errors in the HH, AH, and HA conditions than did early adults (t(56) = 3.62, p = .001, d = 0.96; t(56) = 3.62, p = .001, d = 0.96; t(56) = 3.85, p = .001, d = 1.02, respectively). Similarly, adolescents showed higher error rates than adults across all conditions (HH, t(56) = 4.18, p < .001, d = 1.11; AH, t(56) = 4.15, p < .001, d = 1.10; AA, t(56) = 3.29, p = .004, d = 0.87; HA, t(56) = 4.64, p < .001, d = 1.23). However, no significant differences emerged between the early adults and adults in any condition.

Behavioral results.

*p < .05, **p < .001.

Abbreviations: HH, Happy face followed by happy face; AH, Angry face followed by happy face; AA, Angry face followed by angry face; HA, Happy face followed by angry face.

Regarding reaction times (RTs), there were significant main effects of emotional valence (F(1, 88) = 65.88, p < .001, η² = 0.43), emotional status (F(1, 88) = 62.53, p < .001, η² = 0.42), and group (F(2, 88) = 5.46, p = .006, η² = 0.11). As illustrated in Fig. 2c, post hoc comparisons revealed that adolescents responded more slowly than adults in the HH (t(56) = 3.17, p = .006, d = 0.84), AH (t(56) = 2.68, p = .026, d = 0.71), AA (t(56) = 2.72, p = .023, d = 0.72), and HA (t(56) = 4.07, p < .001, d = 1.08) conditions. Moreover, adolescents also showed slower responses than early adults specifically in the HA condition (t(56) = 2.73, p = .023, d = 0.72). There was also a significant interaction between the two emotional conditions and group (F(2, 88) = 3.40, p = .038, η² = 0.07). Among adolescents, RTs were slower for HA compared to AA (t(24) = 2.24, p = .035, d = 0.45) and slower for AH compared to HH (t(24) = 5.04, p < .001, d = 1.01). In contrast, early adults and adults showed significantly slower RTs only in AH compared to HH (early adults: t(32) = 9.03, p < .001, d = 1.57; adults: t(32) = 6.18, p < .001, d = 1.08).

In adults, RTs under the AH condition showed a significant negative correlation with the PRI (r = −.44, p < .05; Fig. 2d). No significant correlations were observed in adolescents or early adults. When these correlation coefficients were Fisher’s z-transformed and compared between groups, the adult group’s correlation values differed significantly from both the adolescent group (z = 2.19, p = .029) and the early adult group (z = 3.07, p = .002).

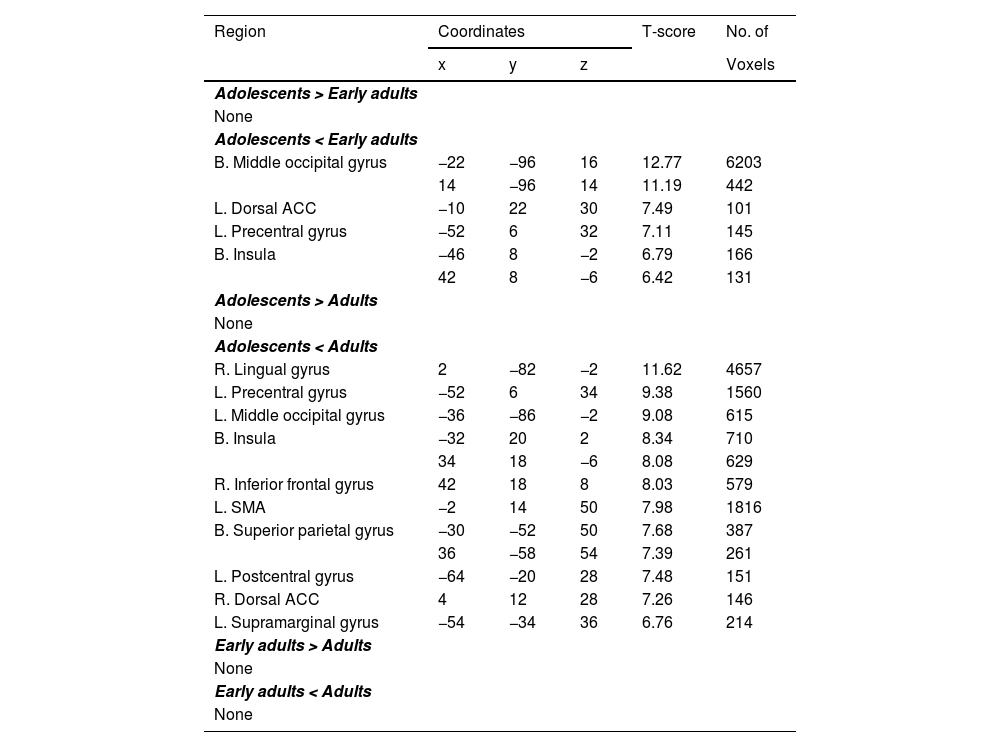

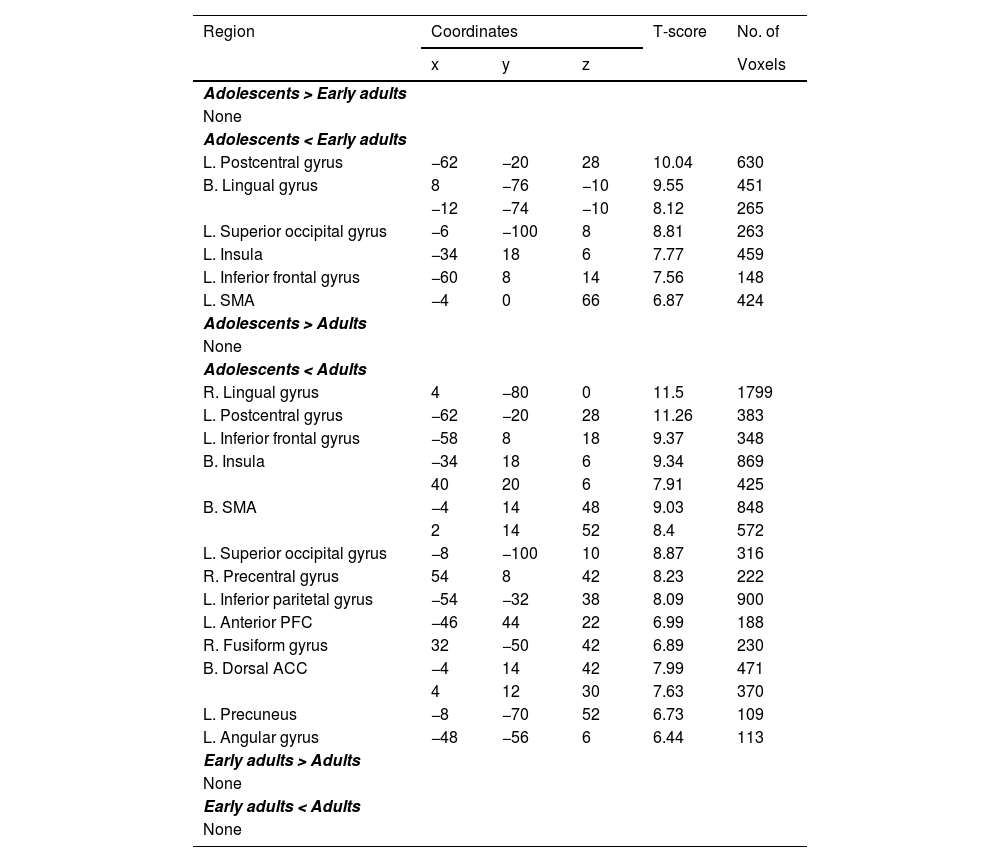

Group differences of neural activations in each conditionGroup-level differences in neural activations for each emotional face condition (HH, AH, AA, and HA) are summarized in Tables 3–6.

Group differences of brain regions showing significant activation under HH.

Clusters with peak-level and FWE-corrected p < .001 and >100 voxels are reported.

Abbreviations: HH, Happy face followed by happy face; L., Left; R., Right; B., Bilateral; ACC, Anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; SMA, Supplementary motor area; FWE, family wise error.

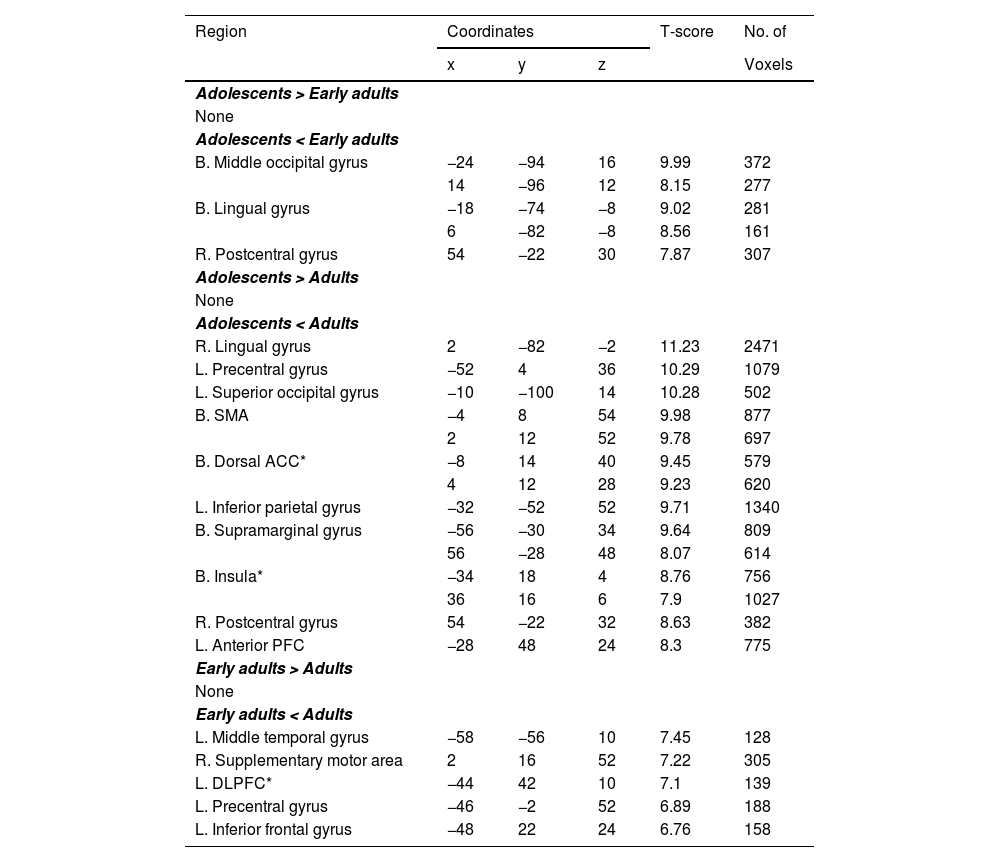

Group differences of brain regions showing significant activation under AH.

Clusters with peak-level and FWE-corrected p < .001 and >100 voxels are reported.

Abbreviations: AH, Angry face followed by happy face; L., Left; R., Right; B., Bilateral; ACC, Anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; SMA, Supplementary motor area; FWE, family wise error; * Region of Interest.

Group differences of brain regions showing significant activation under AA.

Clusters with peak-level and FWE-corrected p < .001 and >100 voxels are reported.

Abbreviations: AA, Angry face followed by angry face; L., Left; R., Right; B., Bilateral; ACC, Anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; SMA, Supplementary motor area; FWE, family wise error.

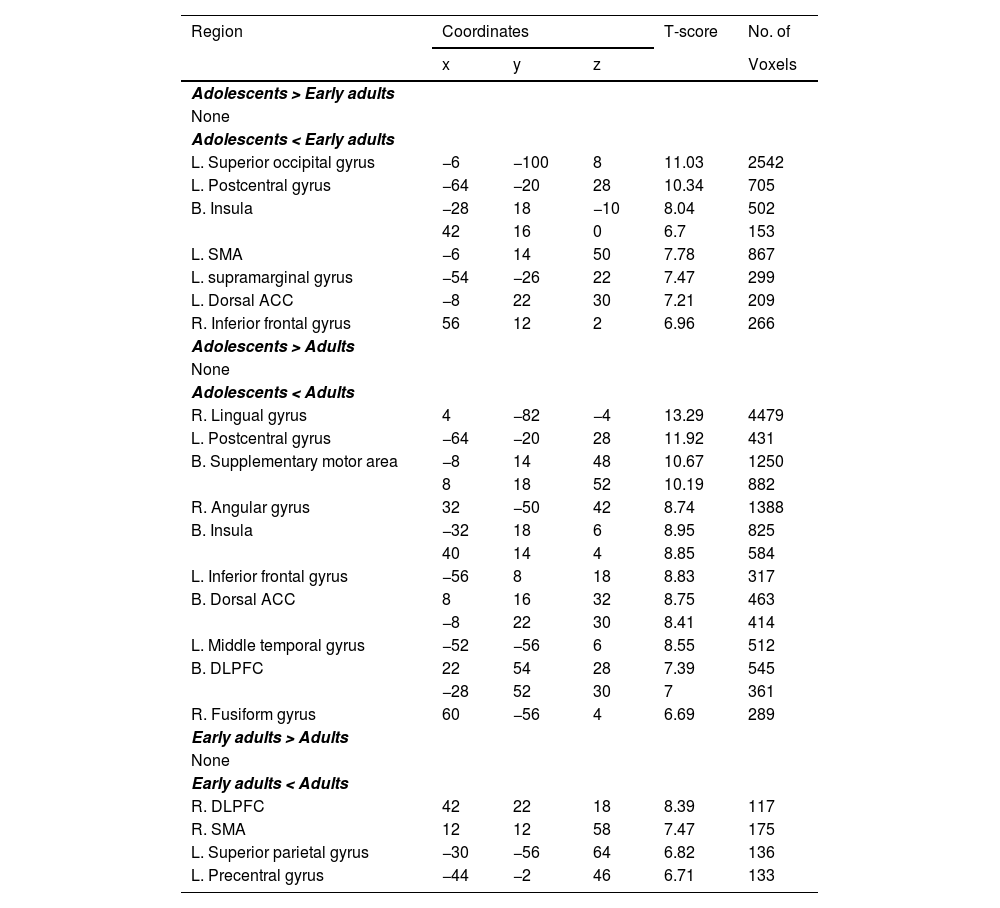

Group differences of brain regions showing significant activation under HA.

Clusters with peak-level and FWE-corrected p < .001 and >100 voxels are reported.

Abbreviations: HA, Happy face followed by angry face; L., Left; R., Right; B., Bilateral; ACC, Anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; SMA, Supplementary motor area; FWE, family wise error.

Compared to early adults, adolescents showed significantly reduced activity in the bilateral middle occipital gyri (MOG), left dACC, left precentral gyrus (PG), and bilateral insula. Furthermore, relative to adults, adolescents exhibited reduced activations in the right lingual gyrus (LG), left PG, left MOG, bilateral insula, right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), left supplementary motor area (SMA), bilateral superior parietal gyrus (SPG), left postcentral gyrus, right dACC, and the left supramarginal gyrus (see Table 3). No significant differences emerged between early adults and adults for HH.

In the AH condition, adolescents displayed lower activation than early adults in the bilateral MOG, bilateral LG, and right postcentral gyrus. Additionally, adolescents showed less activity than adults in the right LG, left PG, left superior occipital gyrus (SOG), bilateral SMA, bilateral dACC, left inferior parietal gyrus (IPG), bilateral supramarginal gyrus, bilateral insula, right postcentral gyrus, and anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC). Early adults, in turn, exhibited significantly lower activations than adults in the left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), right SMA, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), left PG, and left IFG (Table 4).

Under the AA condition, adolescents showed reduced activity relative to early adults in the left postcentral gyrus, bilateral LG, left SOG, left insula, left IFG, and left SMA. Comparing adolescents to adults, reduced activity was observed in the right LG, left postcentral gyrus, left IFG, bilateral insula, bilateral SMA, left SOG, right PG, left IPG, left aPFC, right fusiform gyrus (FG), bilateral dACC, left precuneus, and left angular gyrus (Table 5). There were no significant differences between early adults and adults for AA.

In the HA condition, adolescents showed significantly lower activations than early adults in the left SOG, left postcentral gyrus, bilateral insula, left SMA, left supramarginal gyrus, left dACC, and right IFG. Adolescents also exhibited reduced activation compared to adults in the right LG, left postcentral gyrus, bilateral SMA, right angular gyrus, bilateral insula, left IFG, bilateral dACC, left MTG, bilateral DLPFC, and right FG (Table 6). Additionally, early adults demonstrated lower activation than adults in the right DLPFC, right SMA, left SPG, and left PG under HA.

Group differences of percent signal changes in ROIsAs shown in Fig. 3a, the region-of-interest (ROI) analysis in the dACC revealed significant main effects of emotional expression (F(1,88) = 18.32, p < .001, η² = 0.17) and age group (F(2,88) = 24.06, p < .001, η² = 0.35). The dACC was more strongly activated during happy faces than angry faces. Regarding group differences, adolescents exhibited significantly lower activation in the dACC than early adults in the HH (t(56) = −4.14, p < .001, d = −1.10), AH(t(56) = −4.14, p < .001, d = −1.10), and HA conditions (t(56) = −4.26, p < .001, d = −1.13) and in the AA condition (t(56) = −3.44, p = .003, d = −0.91). Adolescents also showed lower activation than adults across all conditions (HH, (t(56) = −5.17, p < .001, d = −1.37); AH, (t(56) = −6.61, p < .001, d = −1.75); AA, (t(56) = −5.11, p < .001, d = −1.35); HA, (t(56) = −4.90, p < .001, d = −1.30). On the other hand, early adults showed lower activation relative to adults only in the AH condition (t(64) = −2.66, p = .028, d = −0.66).

Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of brain activity for emotional faces across age groups. (a) The ROI analysis for the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC). (b, c) ROI analysis for the bilateral insula. (d) ROI analysis for the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). AA, angry face followed by angry face; AH, angry face followed by happy face; HA, happy face followed by angry face; HH, Happy face followed by happy face.

Turning to the insula (Figs. 3b and 3c), there were significant main effects of facial emotional expression (Left: F(1,88) = 10.55, p = .002, η² = 0.11; Right: F(1,88) = 18.26, p < .001, η² = 0.33) and age group (Left: F(2,88) = 21.95, p < .001, η² = 0.33; Right: F(2,88) = 21.45, p < .001, η² = 0.33). Bilateral insula activity was higher for happy faces than for angry faces. In terms of group comparisons, post hoc tests indicated that adolescents exhibited significantly lower bilateral insula activity than adults in all conditions (Left: HH, t(56) = −5.37, p < .001, d = −1.42; AH, t(56) = −6.61, p < .001, d = −1.75; AA, t(56) = −4.29, p < .001, d = −1.14; HA, t(56) = −5.42, p < .001, d = −1.44; Right: HH, t(56) = −5.03, p < .001, d = −1.33; AH, t(56) = −6.19, p < .001, d = −1.64; AA, t(56) = −5.04, p < .001, d = −1.34; HA, t(56) = −4.86, p < .001, d = −1.29). Similarly, adolescents showed lower activation than early adults in the left insula (HH, t(56) = −4.63, p < .001, d = −1.23); AH t(56) = −3.96, p < .001, d = −1.05); AA, t(56) = −3.54, p = .002, d = −0.94; HA (t(56) = −4.90, p < .001, d = −1.30), and right insula (HH, t(56) = −3.52, p = .002, d = −0.93; AH, t(56) = −3.72, p = .001, d = −0.99; AA, t(56) = −3.28, p = .005, d = −0.87; HA, t(56) = −4.02, p < .001, d = −1.07). On the other hand, early adults differed from adults only in the AH condition (Left: t(64) = −2.85, p = .016, d = −0.70; Right: t(64) = −2.67, p = .027, d = −0.66).

Lastly, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Fig. 3d) displayed significant main effects of facial emotional expression (F(1,88) = 8.67, p = .004, η² = 0.12) and age group (F(2,88) = 12.02, p < .001, η² = 0.21). Similar to the dACC and insula, left DLPFC activation was higher during happy-face trials than angry-face trials. Post hoc multiple comparisons indicated that adolescents showed substantially lower left DLPFC activity than adults in HH (t(56) = −3.61, p = .002, d = −0.96), AH (t(56) = −3.50, p = .002, d = −0.93), and HA (t(56) = −3.04, p = .009, d = −0.81). Early adults exhibited lower activation than adults under all conditions (HH, t(64) = −3.25, p = .005, d = −0.80; AH, t(64) = −4.26, p < .001, d = −1.05; AA, t(64) = −3.48, p = .002, d = −0.86; HA, t(64) = −3.05, p = .009, d = −0.75). However, there were no significant differences between adolescents and early adults in the left DLPFC.

Functional connectivity in SNFig. 4 presents the generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analysis results, using the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) as a seed region for each facial emotion condition. A task-dependent increase in functional connectivity was observed exclusively between the dACC and the right insula [46,−2,−8] (148 voxels) in the AH condition compared to the HH condition (Fig. 4a). In terms of group differences based on post hoc comparisons, adolescents showed greater dACC–insula connectivity than adults in AH (t(56) = 3.83, p < .001, d = 1.02). In HA, adolescents also exhibited lower connectivity than early adults (t(56) = −2.50, p = .045, d = −0.66) (Fig. 4b).

Functional connectivity of the dACC with the right insula during emotional transition conditions. (a) Task-dependent functional connectivity (FC) of the dACC with the right insula during the AH condition presentation compared with the HH condition. The dACC was used as the seed region. (b) Significant main effects of emotional expression and transition on FC strength. (c) No correlation was found between the FC and reaction time in any group during AH presentation. (d) The variations in the correlation of FC and reaction time during HA presentation. AA, angry face followed by angry face; AH, angry face followed by happy face; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; HA, Happy face followed by angry face; HH, happy face followed by happy face; R. Ins, right insula; RT, reaction time.

Although no significant correlations emerged between dACC–insula connectivity strength and reaction time (RT) in any group during AH (Fig. 4c), there were notable differences during HA (Fig. 4d). Specifically, adolescents demonstrated a significant negative correlation between connectivity strength and RT (r = −.44, p < .05), whereas neither early adults nor adults showed a reliable association. Fisher’s z-transformed comparisons indicated that this correlation differed significantly between adolescents and early adults (z = 2.4, p < .05).

DiscussionTo understand age-related differences in emotional facial processing underlying social cognition, we examined both behavioral and neural differences in facial affect recognition among three groups. The current study revealed significant age-related differences in error rates and reaction times during emotional face discrimination tasks. Adolescents exhibited higher error rates and slower responses than both early adults and adults, in line with previous research on the developmental trajectory of cognitive control and emotion regulation (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Fombouchet et al., 2024; Passarotti et al., 2009; Tottenham et al., 2011). Specifically, adolescents had markedly slower responses in conditions involving rapid emotional transitions (e.g., AH or HA), suggesting that the cognitive flexibility required to switch between emotional states may still be maturing during this developmental stage (Bunge & Crone, 2009; McRae et al., 2012; Parr et al., 2024). Meanwhile, early adults performed comparably to adults in terms of error rates.

In addition, a significant negative correlation between perceptual reasoning ability and reaction time emerged in the adult group during AH, implying that individual differences in emotional face processing become more pronounced at later stages of development. PRI is thought to reflect the capacity to interpret and organize visually perceived material, as well as to engage in problem-solving (Clark et al., 2021). Therefore, PRI could be related to social cognition (Penuelas-Calvo et al., 2021), as it may contribute to an individual’s ability to recognize others’ facial expressions (Lee et al., 2014) and generate appropriate responses.

Neural activity during emotional face recognitionA crucial finding of our ROI analyses is the pronounced developmental gap in activation within the SN—composed of the dACC and bilateral insula—between adolescents and the adult groups (i.e., early adults and adults). In emotional facial processing, adolescents consistently exhibited reduced dACC and insular activation, reflecting a less mature engagement in monitoring and modulating emotional responses (Bastin et al., 2017; Molnar-Szakacs & Uddin, 2022). Interestingly, the early adult group (19–24 years) tended to more closely resemble the adults (25–34 years) than they did the adolescents, suggesting that SN maturation may be largely complete by early adulthood (Supekar & Menon, 2012; Uddin, 2017). Previous study has reported that SN are associated with prosocial behavior during adolescent development (Sipes et al., 2022). Thus, in line with previous research, SN function appears to be a neural developmental marker that differentiates adolescents—who are still refining their social-emotional processing—from more mature adult cohorts.

By contrast, activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) showed a different pattern of age-related differences. Here, the most notable contrasts emerged between the adult group (≥25 years) and the two younger groups (adolescents and early adults), with adolescents and early adults exhibiting similarly lower DLPFC activation relative to the adults. This finding implies that full DLPFC maturation, which underlies advanced executive functions such as cognitive reappraisal and top-down emotion regulation, may extend beyond early adulthood (Shinpei et al., 2024; Yan et al., 2024). The DLPFC is heavily involved in cognitive reappraisal, a strategy used to regulate emotions by changing the interpretation of emotional stimuli. Previous study has shown that the DLPFC is activated during reappraisal tasks, indicating its role in modulating emotional responses (Shinpei et al., 2024). During adolescence and early adulthood, the DLPFC undergoes significant maturation, which enhances its ability to process social information and engage in complex social interactions (Yan et al., 2024). In other words, while the SN may reach near-adult levels of functionality by the early 20 s, the DLPFC seems to represent a more “final stage” biomarker of social-cognitive development. Such prolonged DLPFC maturation aligns with models positing that complex executive functions and higher-order social cognition—integral for nuanced interpersonal interactions—are among the last neural processes to solidify (Dumontheil, 2016; Popplau & Hanganu-Opatz, 2024).

Taken together, these differential activation patterns in the SN versus the DLPFC underscore distinct developmental trajectories for core regions subserving social-emotional and cognitive control processes. The SN may be especially critical in distinguishing adolescent from adult-level responsiveness to emotional face, thus functioning as a “neurodevelopmental marker” for social cognition. The DLPFC, in contrast, may reflect the transition toward a fully mature social-cognitive architecture, as its activation profile clearly sets adults (≥25 years) apart from both adolescents and early adults. Understanding how these regions evolve offers valuable insights into when and how individuals acquire robust social-emotional regulation and higher-order cognitive skills.

Differences in functional connectivity networks among ages groupsThis study aimed to investigate if the engagement of the SN in responding to emotional stimuli depends on age group. The SN, known for its involvement in detecting and integrating emotional and sensory stimuli, is crucial for guiding behavior and cognitive processing based on the relevance of external events and internal states (Downar et al., 2002; Menon & Uddin, 2010; Seeley, 2019). The SN plays an essential role in efficiently detecting and integrating important internal and external stimuli, as well as in switching between the default mode network and the central executive network (Schimmelpfennig et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). However, when the SN is overactive or underperforming, different types of cognitive deficits could appear (Weng et al., 2019). The dACC and the insula are key components of this network, working together to assess the salience of emotional and sensory information (Luo et al., 2014; Seeley et al., 2007). Particularly, the dACC, which selected seed ROI in this study, plays a crucial role in goal-directed behavior, and its operation reflects the fundamental need for adaptability (Clairis & Lopez-Persem, 2023).

A key contribution of this study lies in the contrasting connectivity patterns observed across the AH and HA conditions. While prior research often centers on univariate activation using emotional stimuli or functional connectivity based on resting state, our gPPI analysis offers a more specific perspective on how the SN responds to emotional transition cues. When participants discriminated the emotional valence of AH, adolescents maintained stronger dACC–insula connectivity than adults. Previous study has indicated that SN is involved in causing bias in the processing of negative information (Hamilton et al., 2016). In other words, although the emotional context had shifted from negative to positive, the adolescent salience network appeared to carry forward its processing of the preceding angry stimulus. Heightened salience processing may overload cognitive resources, making it more difficult for individuals to flexibly switch between tasks or adapt to changing priorities (Hermans et al., 2014; Menon & Uddin, 2010). Previous studies have reported that emotional regulation is less developed in early adolescence (McRae et al., 2012), and that adolescents exhibit higher switch costs in emotional regulation tasks compared to adults (Samson et al., 2022). Moreover, individual differences in adolescent responses to social stimuli imply that this developmental period is particularly sensitive to emotional change (Silvers et al., 2012). Therefore, this residual effect may reflect a more prolonged negative emotional detection mode, potentially hindering the rapid recalibration required to engage with the now-positive emotional cue.

By contrast, in the HA condition, adolescents revealed significantly reduced SN connectivity compared to early adults. The adolescents were failing to properly activate the SN and thus was unable to adaptively respond to this newly threatening context. Consequently, while adolescents performed worse overall in both AH and HA, the underlying neural mechanisms were distinct. In AH, they were overly engaged with prior negative information, whereas in HA, they failed to adequately reengage for the emergent negative cue. When the SN underperforms, individuals might have struggled to recognize or respond to emotionally significant events, potentially leading to apathy or diminished emotional engagement (Craig, 2009; Di Martino et al., 2009; Uddin & Menon, 2009). Additionally, this situation can result in reduced cognitive flexibility (Limongi et al., 2020). Furthermore, dACC–insula connectivity in HA correlated with reaction times exclusively for adolescents. Adolescents with weakened SNs revealed difficulty in switching attention and adjusting behavior when faced with negative stimuli.

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of the salience network (SN) plays an important role in deciding whether to continue or switch cognitive strategies (Dajani & Uddin, 2015; Kim et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015; Monosov & Rushworth, 2022) and is associated with behavioral responses in cognitive flexibility tasks (Thomas et al., 2023). Our findings suggest that adolescents can become hyper-focused on past negative contexts (AH) yet remain unprepared for newly emerging negative contexts (HA). Therefore, the involvement of the SN appears to be crucial for determining how quickly adolescents adapt to novel social signals. Such patterns may help explain why adolescents are particularly susceptible to social-emotional stress when cognitive flexibility declines (Debra et al., 2024). These distinct functional connectivity profiles highlight the SN’s pivotal function in dictating how efficiently individuals update their emotional responses and point to potential targets for interventions aimed at bolstering adolescent resilience and lowering the risk of future psychopathology (Jones et al., 2023; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2023; Schwartz et al., 2019).

Cultural context and generalizability in facial emotion processingCultural differences significantly influence the interpretation of facial expressions, affecting both perception (Ikeda, 2025) and production of emotions (Fang et al., 2021; Siritanawan et al., 2023). While cultural differences play a crucial role in interpreting facial expressions, some researchers argue that certain emotional expressions may still retain universal characteristics, suggesting a complex interplay between culture and innate emotional responses (Gong et al., 2025). In this study, experiments were conducted using facial stimuli selected from photographs in the KOFEE database (Lee et al., 2014), with Korean participants. In this process, culturally specific emotional expressions and perceptual processing in Korean may have influenced the results. Therefore, these findings contribute to understanding brain development patterns in Korean adolescents and suggest that research should be expanded across diverse cultural contexts to observe universal brain development patterns in facial emotion processing.

LimitationsDespite the strengths and novel insights provided by this study, several limitations warrant consideration. First, this research employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer causal relationships or delineate developmental trajectories over time. Future studies could adopt longitudinal methods to better capture how neural and behavioral processes evolve from adolescence into adulthood. Second, although the sample size was adequate to detect the reported effects, it may not capture the full heterogeneity across developmental stages, limiting generalizability. Building on our finding that adolescents showed altered dACC–insula connectivity during emotional transitions, future work will apply Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to the fMRI time series to characterize brain-state dynamics. To appropriately power these HMM analyses and robustly validate developmental differences in state transitions, we will expand to a larger and more diverse sample. Third, the study focused primarily on the salience network and prefrontal regions, meaning that other networks (e.g., default mode network, fronto-parietal network) potentially involved in emotional regulation and cognitive control were not fully explored. Addressing these limitations in subsequent studies would not only help validate the current findings but also contribute to a more detailed understanding of how social-emotional and cognitive processes evolve across adolescence and early adulthood.

ConclusionThis study provides novel insights into age-related differences in both behavioral performance and neural functioning during emotional facial processing across adolescence, early adulthood, and adulthood. Adolescents showed higher error rates and longer reaction times, particularly in tasks requiring rapid shifts between emotional states. Neuroimaging analyses revealed pronounced developmental gaps in the salience network (SN) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), suggesting that these regions mature at different rates. Specifically, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and insula—key nodes of the SN—appear to function as earlier neurodevelopmental markers, discriminating adolescents from older groups, whereas the DLPFC may represent a later-stage biomarker, differentiating adults (≥25 years) from both adolescents and early adults.

Furthermore, functional connectivity analyses demonstrated that adolescents are prone to over-sustaining threat-related network engagement in an angry-to-happy transition, yet under-recruit salience processing in the opposite (happy-to-angry) condition. These distinct patterns appear to underlie adolescents’ elevated error rates and reduced flexibility when updating emotional responses. Taken together, these findings underscore the protracted and region-specific neural maturation underlying social-emotional regulation and emphasize the clinical relevance of targeting salience network and prefrontal connectivity for interventions aimed at bolstering adolescent resilience. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to clarify how these neural mechanisms evolve over time and to explore the potential utility of these findings in preventing or mitigating mental health challenges associated with developmental transitions.

FundingThis research was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program-Robot Industrial Technology Development) (20018699) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea), by a grant of the Mental Health related Social Problem Solving Project, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS-2024-00409864), and the Basic Medical Science Facilitation Program through the Catholic Medical Center of the Catholic University of Korea funded by the Catholic Education Foundation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJi-Won Chun: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Software, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Jihye Choi: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. Arom Pyeon: Investigation, Validation. Minkyung Hu: Investigation, Validation. Hyun Cho: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation. Jung-Seok Choi: Conceptualization. Kook-Jin Ahn: Methodology. Jong-Ho Nam: Conceptualization, Methodology. Inyoung Choi: Conceptualization, Data curation. Dai-Jin Kim: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.