Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoThe global incidence of oncological disease is rising, driven by increased longevity and greater exposure to carcinogens. Pain remains one of the most prevalent and disabling symptoms among cancer patients, requiring urgent evaluation and treatment. However, selecting an effective therapeutic approach remains a challenge. Neuromodulation techniques such as Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) and Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) have shown promise in managing chronic pain across various conditions, but evidence in the oncological context is still limited. This study systematically reviewed the effects of rTMS and tDCS on cancer pain management. A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, and CENTRAL, following PRISMA guidelines, yielding 657 potentially relevant studies. Quality assessment was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist. Eight randomized controlled trials from four countries were included, involving 349 patients: three employing rTMS and five using tDCS. The studies examined diverse patient groups, cancer types, and neuromodulation protocols, producing mixed but generally short‑term reductions in pain. Indirect evidence suggests that rTMS may induce faster but shorter‑lived analgesia, whereas tDCS may be associated with modest persistence when delivered in repeated sessions. Overall, the findings provide preliminary evidence that non‑invasive brain stimulation techniques may contribute to cancer pain management. Future research should optimize stimulation parameters, conduct direct comparisons, and explore integration with pharmacological and behavioral strategies to enhance long‑term effectiveness.

Oncological disease is a highly stressful event, and its negative impact on patients' quality of life is widely reported (Paredes, 2015; Popa-Velea et al., 2017). Factors such as uncertainty, complex medical decisions, therapy choices, and the changing perspectives on the future make the experience particularly challenging (Paredes, 2015; Cordova et al., 2017). The global incidence of cancer has been increasing, partly due to longer life expectancy and greater exposure to carcinogens. According to epidemiological data, there were 19.9 million new cancer cases in 2022, with approximately 53.5 million people currently living with cancer worldwide. In Europe, the rate was about 280 new cases per 100,000 people (Ferlay et al., 2024).

Despite advances in early detection and treatment, cancer continues to cause various short- and long-term side effects, with pain being one of the most significant (Straub, 2005). Cancer pain is influenced by factors such as tumor type, progression, invasion, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, and disease-related infections (Oliveira et al., 2016; Prinsloo et al., 2014). It is a subjective and individual experience that involves physical, cognitive, cultural, and psychological manifestations (Oliveira et al., 2016).

When uncontrolled, cancer pain can lead to anxiety, depressive symptoms, and cognitive impairments, disrupting daily and social activities (Miceli, 2002). Pain is often described as intolerable, especially in advanced stages of cancer, affecting 64 % of patients (Graner et al., 2010), with approximately 45 % of those with advanced cancer experiencing moderate to severe pain (Brozovic et al., 2022). Additionally, pain negatively impacts the quality of life, contributing to insomnia, fatigue, increased disability, and reduced adherence to treatment (Marshall et al., 2012; Pergolizzi et al., 2014). Ineffective pain control can lead to social isolation (Lema et al., 2010; Pergolizzi et al., 2014; Simone et al., 2012) and can also affect family members and caregivers (Raphael et al., 2010). A systematic review of 104 studies identified pain as a significant predictor of survival time in cancer patients (Montazeri, 2009).

Chronic pain, defined as persistent or recurrent pain lasting more than three months (Bennett et al., 2019), affects 33–40 % of cancer survivors, with 5–10 % experiencing pain that significantly interferes with functionality (Fallon et al., 2018). Although pain management is a routine aspect of cancer care, chronic pain remains a significant challenge for healthcare professionals, patients, and survivors alike (Prinsloo et al., 2014). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN, 2025) considers severe, uncontrolled cancer pain a medical emergency that requires immediate assessment and treatment, typically involving a combination of analgesics ranging from basic medications to strong opioids.

While pharmacological interventions help manage pain, they can have adverse effects, such as drowsiness, memory impairment, and weakness (Araújo et al., 2011). Consequently, there is a growing need for alternative therapeutic strategies to mitigate cancer pain (Li et al., 2023). In this context, non-invasive neuromodulation is an expanding field in pain medicine that employs non-surgical methods to modulate neural function and mitigate pain. According to the International Neuromodulation Society (2021), neuromodulation is described as the alteration of nerve activity through the focused application of stimuli, whether electrical or chemical, in specific neurological regions. These therapies include deep stimulation of the cerebral motor cortex, peripheral nerve stimulation and the non-invasive brain stimulation techniques (NIBS) of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (Knotkova et al., 2021). Among these tDCS and TMS seem to have a clinically relevant impact. These brain stimulation methods can focally modulate cortical excitability and are associated with mild and painless adverse effects, making them promising in the investigation of new approaches to pain relief (Williams et al., 2009; Fernandes et al., 2024). Recent neuroimaging and neuromodulation research provides converging evidence supporting the selection of both the primary motor cortex (M1) and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) as therapeutic targets in cancer-related pain. Stimulation of M1 has been shown to engage descending inhibitory pain pathways involving the thalamus, periaqueductal gray, and rostral ventromedial medulla, thereby modulating nociceptive processing and central sensitization (Bai et al., 2024). In parallel, modulation of the PFC—particularly the dorsolateral region—appears to influence the cognitive-affective and evaluative dimensions of pain perception. Preliminary findings in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemoradiation therapy demonstrated that tDCS over the PFC reduced prefrontal-somatosensory connectivity and altered EEG activity, suggesting that targeting this region may attenuate cancer-related pain through top-down regulation of pain networks (de Souza Moura et al., 2022).

Both TMS and tDCS have been employed in research aimed at exploring their potential effectiveness in managing chronic pain across oncologic and non-oncologic populations. Much of the available evidence comes from studies on non-oncologic chronic pain, which provide important insights into mechanisms and potential applicability to cancer-related pain. Several studies have suggested that TMS may alleviate chronic pain, especially neuropathic pain (Muller et al., 2013). Existing literature indicates M1 stimulation with TMS may be associated with improvements in drug-resistant and refractory neuropathic pain (Hirayama et al., 2006; Lefaucheur et al., 2014), and it may also hold potential for addressing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Significant effects of TMS have also been observed in fibromyalgia, supporting its consideration as a therapeutic technique for controlling refractory pain in clinical practice (Araújo et al., 2011). Despite these promising findings, one limitation of the TMS technique appears to be the relatively short duration of its analgesic effect. Ongoing research is therefore exploring strategies to prolong these benefits (Zang et al., 2021). In oncology-specific contexts, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may alleviate pain in patients with non-brain cancers, highlighting its potential as a non-invasive brain stimulation method for cancer-related pain management (Chien et al., 2023). However, since this meta-analysis included only two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), its findings should be interpreted with caution.

On the other hand, tDCS has been applied to chronic pain associated with various diseases and neurological dysfunctions across individuals of all ages (Pinto et al., 2018). Recognized as a safe and promising alternative to pharmacological treatments (Pacheco-Barrios et al., 2020), tDCS is primarily used on the M1 and the PFC (Silva et al., 2020). These targets are neurobiologically relevant for pain modulation: M1 stimulation can influence thalamocortical pathways and descending inhibitory systems, while PFC stimulation is associated with affective and cognitive regulation of pain perception. In addition to its potential pain-relieving effects, tDCS has been reported to reduce stress and anxiety—frequent consequences of chronic pain—thereby promoting overall relief (Capetti et al., 2024; Silva et al., 2018). A recent scoping review also highlighted possible benefits of tDCS in alleviating pain and improving neurocognitive functions in patients with different cancer types, including breast, head and neck, pancreatic cancers, and meningioma. However, these findings remain fragmented and preliminary, and systematic evidence defining its specific benefits for cancer pain management is still lacking (Capetti et al., 2024).

Although both tDCS and TMS have shown potential benefits for neuropathic and other types of chronic pain, evidence regarding their efficacy remains mixed, particularly for neuropathic pain and headaches (Knotkova et al., 2021), which are common among cancer patients. Nonetheless, targeted tDCS has shown promise as a clinical strategy, including in oncology settings (Nascimento et al., 2022). When comparing the two techniques, some studies suggest that rTMS may be more effective for certain types of neuropathic pain. For instance, in patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy, rTMS significantly reduced pain compared to tDCS and placebo treatments (Attal et al., 2016). On the other hand, tDCS has also demonstrated moderate effectiveness in various studies addressing chronic pain (Wen et al., 2022; Zortea et al., 2019).

The effects of both techniques tend to last for days to weeks after treatment. For example, tDCS has been shown to maintain its analgesic effects for three to four weeks post-intervention (Antal et al., 2010), while rTMS has provided relief lasting from several days to weeks (Attal et al., 2016). An important distinction between the two methods is accessibility. tDCS is portable and more affordable, making it suitable for use in diverse settings, including at home (Funke, 2013). In contrast, TMS equipment is expensive and non-portable, restricting its use to clinical or laboratory environments (Funke, 2013).

Although there are several studies on the use of neuromodulation for pain management, the literature focused specifically on cancer patients remains limited. These studies vary in the techniques employed—often including invasive methods—and in the outcomes assessed, such as pain, anxiety, and depression (Chien et al., 2023; D’Souza et al., 2022). Furthermore, existing review studies often integrate different types of outcomes, which complicates efforts to systematize the current evidence on the use of TMS and tDCS for managing cancer-related pain.

Thus, this systematic review aimed to address this gap by focusing on synthesizing the effects of TMS and tDCS in managing pain in cancer patients. Since these interventions have not yet been widely adopted, particularly for chronic cancer-related pain, this analysis is significant as it explores non-pharmacological alternatives that avoid medication-related side effects and highlights directions for future research.

MethodsThis systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, which ensure methodological transparency, reduce bias, and support the generation of robust and reproducible conclusions (Page et al., 2021). The present study was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with reference number CRD42025635416. The PROSPERO protocol did not pre-specify subgroup or sensitivity analyses due to the expected heterogeneity in cancer types, stimulation protocols and outcome measures.

Literature searchThe literature search for evidence was conducted using the following electronic databases: PUBMED, Web of Science, Scopus, Proquest and CENTRAL through a combination of the following words: cancer’, ‘oncology’, ‘neoplasm’, ‘carcinoma’, ‘pain’, ‘transcranial magnetic stimulation’, ‘transcranial electrical stimulation’, ‘transcranial direct current stimulation’ and ‘neuromodulation’. The Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used to combine the key terms. A detailed description of the search strategy is available in Supplementary Table S1. Specific filters related to restrictions on the year and language of publication were also considered. The initial search was conducted in November 2023, and an updated search was reconducted in September 2025. No additional studies were included, as none met the pre-specified inclusion criteria.

Eligibility criteriaRegarding the inclusion criteria, and considering the PICO approach, the review included (i) studies involving individuals over the age of 18, (ii) diagnosed with an oncological disease and experiencing pain (population); (iii) and previously submitted to TMS or tDCS (intervention). The studies also had to include an assessment of pain (pain intensity was defined as the primary outcome of the review) in comparison with a control group (sham group) and/or a group receiving standard care (comparator). The review only included studies with a randomized controlled design (RCTs), published in the last 20 years, in Portuguese, English or Spanish to ensure accessibility and relevance. Protocols, conference proceedings or abstracts, book chapters and editorials were excluded from the study.

Data selection and extraction processThe initial selection process was supported by a semi-automated tool - Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/). Rayyan’s automated deduplication feature was used to remove duplicate records prior to screening, and no additional automation tools were used during screening or data extraction. After deduplication, two independent reviewers (JP and SF) examined the search results based on titles and abstracts and applied the eligibility criteria, a process conducted between November and December 2023. Inter-rater agreement between the two reviewers was 83 %, and any conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (AB).

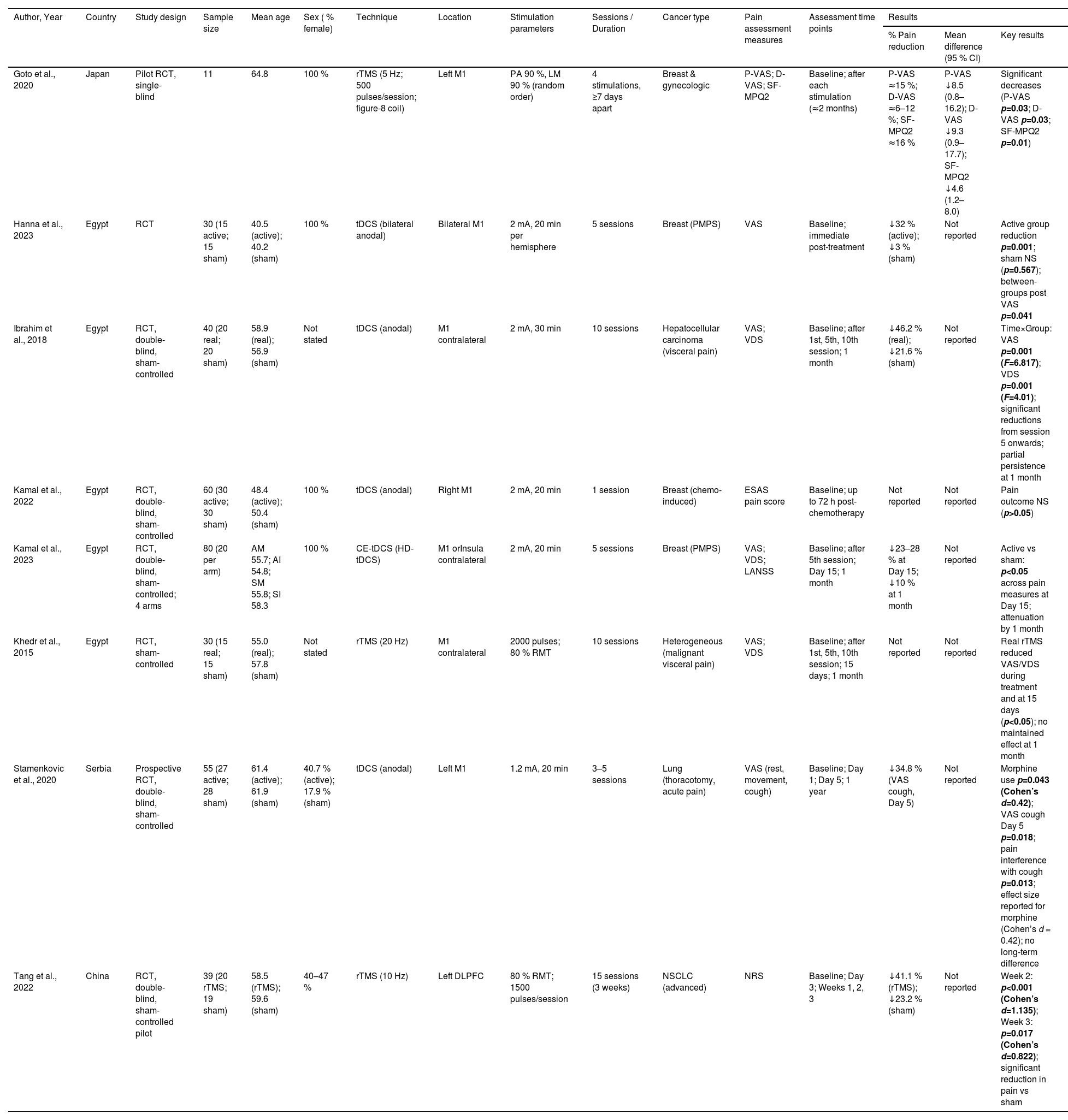

The full texts of the selected publications were then analyzed, and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. After full-text assessment, the following data were extracted independently by the reviewers: author, year of publication, study design, sample size, mean age, percentage of females, stimulation technique, cancer type, pain assessment measures, and main results. Extracted data were compiled in Table 1.

Characteristics and pain outcomes of included studies.

| Author, Year | Country | Study design | Sample size | Mean age | Sex ( % female) | Technique | Location | Stimulation parameters | Sessions / Duration | Cancer type | Pain assessment measures | Assessment time points | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Pain reduction | Mean difference (95 % CI) | Key results | |||||||||||||

| Goto et al., 2020 | Japan | Pilot RCT, single-blind | 11 | 64.8 | 100 % | rTMS (5 Hz; 500 pulses/session; figure-8 coil) | Left M1 | PA 90 %, LM 90 % (random order) | 4 stimulations, ≥7 days apart | Breast & gynecologic | P-VAS; D-VAS; SF-MPQ2 | Baseline; after each stimulation (≈2 months) | P-VAS ≈15 %; D-VAS ≈6–12 %; SF-MPQ2 ≈16 % | P-VAS ↓8.5 (0.8–16.2); D-VAS ↓9.3 (0.9–17.7); SF-MPQ2 ↓4.6 (1.2–8.0) | Significant decreases (P-VAS p=0.03; D-VAS p=0.03; SF-MPQ2 p=0.01) |

| Hanna et al., 2023 | Egypt | RCT | 30 (15 active; 15 sham) | 40.5 (active); 40.2 (sham) | 100 % | tDCS (bilateral anodal) | Bilateral M1 | 2 mA, 20 min per hemisphere | 5 sessions | Breast (PMPS) | VAS | Baseline; immediate post-treatment | ↓32 % (active); ↓3 % (sham) | Not reported | Active group reduction p=0.001; sham NS (p=0.567); between-groups post VAS p=0.041 |

| Ibrahim et al., 2018 | Egypt | RCT, double-blind, sham-controlled | 40 (20 real; 20 sham) | 58.9 (real); 56.9 (sham) | Not stated | tDCS (anodal) | M1 contralateral | 2 mA, 30 min | 10 sessions | Hepatocellular carcinoma (visceral pain) | VAS; VDS | Baseline; after 1st, 5th, 10th session; 1 month | ↓46.2 % (real); ↓21.6 % (sham) | Not reported | Time×Group: VAS p=0.001 (F=6.817); VDS p=0.001 (F=4.01); significant reductions from session 5 onwards; partial persistence at 1 month |

| Kamal et al., 2022 | Egypt | RCT, double-blind, sham-controlled | 60 (30 active; 30 sham) | 48.4 (active); 50.4 (sham) | 100 % | tDCS (anodal) | Right M1 | 2 mA, 20 min | 1 session | Breast (chemo-induced) | ESAS pain score | Baseline; up to 72 h post-chemotherapy | Not reported | Not reported | Pain outcome NS (p>0.05) |

| Kamal et al., 2023 | Egypt | RCT, double-blind, sham-controlled; 4 arms | 80 (20 per arm) | AM 55.7; AI 54.8; SM 55.8; SI 58.3 | 100 % | CE-tDCS (HD-tDCS) | M1 orInsula contralateral | 2 mA, 20 min | 5 sessions | Breast (PMPS) | VAS; VDS; LANSS | Baseline; after 5th session; Day 15; 1 month | ↓23–28 % at Day 15; ↓10 % at 1 month | Not reported | Active vs sham: p<0.05 across pain measures at Day 15; attenuation by 1 month |

| Khedr et al., 2015 | Egypt | RCT, sham-controlled | 30 (15 real; 15 sham) | 55.0 (real); 57.8 (sham) | Not stated | rTMS (20 Hz) | M1 contralateral | 2000 pulses; 80 % RMT | 10 sessions | Heterogeneous (malignant visceral pain) | VAS; VDS | Baseline; after 1st, 5th, 10th session; 15 days; 1 month | Not reported | Not reported | Real rTMS reduced VAS/VDS during treatment and at 15 days (p<0.05); no maintained effect at 1 month |

| Stamenkovic et al., 2020 | Serbia | Prospective RCT, double-blind, sham-controlled | 55 (27 active; 28 sham) | 61.4 (active); 61.9 (sham) | 40.7 % (active); 17.9 % (sham) | tDCS (anodal) | Left M1 | 1.2 mA, 20 min | 3–5 sessions | Lung (thoracotomy, acute pain) | VAS (rest, movement, cough) | Baseline; Day 1; Day 5; 1 year | ↓34.8 % (VAS cough, Day 5) | Not reported | Morphine use p=0.043 (Cohen’s d=0.42); VAS cough Day 5 p=0.018; pain interference with cough p=0.013; effect size reported for morphine (Cohen’s d = 0.42); no long-term difference |

| Tang et al., 2022 | China | RCT, double-blind, sham-controlled pilot | 39 (20 rTMS; 19 sham) | 58.5 (rTMS); 59.6 (sham) | 40–47 % | rTMS (10 Hz) | Left DLPFC | 80 % RMT; 1500 pulses/session | 15 sessions (3 weeks) | NSCLC (advanced) | NRS | Baseline; Day 3; Weeks 1, 2, 3 | ↓41.1 % (rTMS); ↓23.2 % (sham) | Not reported | Week 2: p<0.001 (Cohen’s d=1.135); Week 3: p=0.017 (Cohen’s d=0.822); significant reduction in pain vs sham |

Notes: CE tDCS / HD tDCS – Concentric electrode / High definition transcranial Direct Current Stimulation; Cohen’s d – standardized effect size; D VAS – Dysesthesia Visual Analog Scale; ESAS – Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; F – ANOVA F statistic; LANSS – Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; LM 90 % / PA 90 % – Latero–Medial or Posterior–Anterior coil orientation at 90 % Resting Motor Threshold (RMT); NRS – Numeric Rating Scale; NS – Not significant; NSCLC – Non Small Cell Lung Cancer; P VAS – Pain Visual Analog Scale; PMPS – Post Mastectomy Pain Syndrome; rTMS – Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; RMT – Resting Motor Threshold; SF MPQ2 – Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire 2; tDCS – Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation; VAS – Visual Analog Scale; VDS – Verbal Descriptor Scale.

Due to substantial heterogeneity in cancer types, stimulation protocols, outcome measures and follow-up durations, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a narrative synthesis of the included studies was conducted over a 4-month period (February–May 2024), incorporating limited quantitative summaries where possible (e.g., percentage pain reduction, changes in self-report scores).

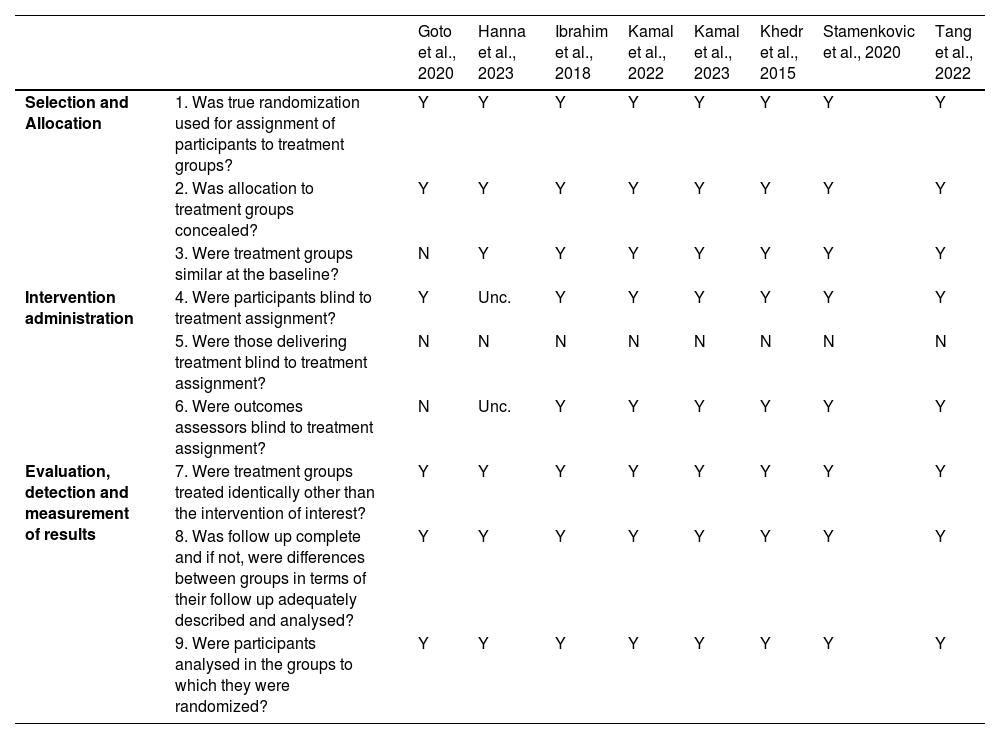

Study qualityTwo reviewers (JP and SF) independently assessed methodological quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for RCTs. Each item on these checklists was assessed as “yes”, “no”, “undetermined” or “not applicable”. Consensus was reached through discussion with a third author (AB), when necessary. The assessment of the methodological quality of the studies was carried out based on the information available in the studies.

In line with JBI methodological guidance, GRADE is mandatory only for reviews of effectiveness that include meta-analyses or comparable quantitative syntheses (Stern et al., 2024). Given the substantial heterogeneity across cancer types, stimulation protocols, outcome measures, and follow-up durations, a meta-analysis was not feasible, making GRADE inappropriate. Certainty of evidence was therefore inferred qualitatively from JBI appraisal scores, with greater confidence attributed to studies that adequately fulfilled key methodological domains, including selection and allocation procedures (randomization and concealment), intervention administration (participant and assessor blinding), evaluation and measurement of results (consistency and reliability of outcome assessment), retention of participants (complete follow-up and appropriate analysis), and statistical conclusion of validity (robust and reliable outcome measurement).

ResultsA total of 657 potentially relevant studies were identified in the databases. After removing duplicate studies, 497 were selected by title and abstract, but 475 did not meet the eligibility criteria. The full texts of the 13 potentially eligible studies were retrieved and 8 studies were included in the study. The PRISMA flowchart of the search process and selection of studies, including the reasons for excluding studies, is shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics and participantsThis review included eight RCTs from Egypt (n = 5), Japan (n = 1), China (n = 1) and Serbia (n = 1). These studies were published between 2015 and 2023 and recruited a total of 349 cancer patients. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 11 to 80 participants (M = 43.63; SD = 21.04). Most participants were female (min. 30 % and max. 100 %) with average ages ranging from 40.35 to 64.80 years (M = 55.71; SD = 7.66). The studies showed heterogeneity in terms of the type of neoplasm, for example 4/8 of the studies included participants with breast carcinoma and 2/8 with lung carcinoma.

Intervention characteristicsThree studies employed repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), while five used transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Most targeted the primary motor cortex (M1), with Goto et al. (2020) and Stamenkovic et al. (2020) specifying the left M1, and Hanna et al. (2023) applying bilateral stimulation. Kamal et al. (2023) uniquely investigated stimulation of the insula contralateral to the painful site. Intervention schedules varied considerably. Kamal et al. (2022) tested a single 20‑minute tDCS session, whereas Goto et al. (2020) delivered four rTMS sessions across two months, testing different active stimulation parameters rather than including a sham control. Multi‑session protocols ranged from 5 to 15 sessions, lasting 20–40 min each. Evaluation moments were heterogeneous: Ibrahim et al. (2018) assessed outcomes up to 1 month post‑treatment; Kamal et al. (2022) at 72 h; Kamal et al. (2023) and Khedr et al. (2015) at 15 days and 1 month; and Stamenkovic et al. (2020) extended follow‑up to 1 year (see Table 1).

Pain assessment measuresPain was assessed using validated scales: Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Pain VAS (P‑VAS), Dysesthesia VAS (D‑VAS), Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), and the Short‑Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF‑MPQ2). Six studies used VAS (Goto et al., 2020; Hanna et al., 2023; Ibrahim et al., 2018; Kamal et al., 2023; Khedr et al., 2015; Stamenkovic et al., 2020), three used VDS (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Khedr et al., 2015; Kamal et al., 2023), and one each used NRS (Tang et al., 2022), ESAS (Kamal et al., 2022), and SF‑MPQ2 (Goto et al., 2020). Four studies combined two scales to capture multidimensional pain outcomes.

Effectiveness of the interventionThe eight randomized trials consistently demonstrated that non‑invasive brain stimulation can produce short‑term analgesic effects in cancer patients, although the magnitude and persistence of benefit varied according to technique, number of sessions, and stimulation parameters. Overall, multi‑session protocols achieved reductions in pain intensity ranging from 20 % to 46 %, while single‑session interventions did not yield significant improvements. tDCS studies showed that at least five sessions were necessary to achieve clinically meaningful reductions. Bilateral stimulation of M1, as tested by Hanna et al. (2023), produced a 32 % decrease in pain scores compared to minimal change in the sham group, with effects reaching statistical significance. Similarly, Kamal et al. (2023) reported significant reductions after five sessions targeting either M1 or the insula, with benefits persisting for up to one month, although attenuation was noted over time. Stamenkovic et al. (2020) also observed improvements after five sessions, particularly in pain associated with coughing, accompanied by reduced morphine use; however, these effects were not sustained at one year. Ibrahim et al. (2018) provided further evidence of the importance of repeated stimulation, showing significant time‑by‑group interactions for both VAS and VDS, with reductions evident from the fifth session and maintained at one month. In contrast, Kamal et al. (2022), who tested a single 20‑minute session, found no significant differences between active and sham groups, underscoring the limited efficacy of isolated stimulation. rTMS protocols revealed a similar pattern of short-term benefit, though requiring a higher number of sessions. Goto et al. (2020) demonstrated significant reductions across multiple pain measures after four sessions, while Khedr et al. (2015) reported relief following ten sessions, with effects persisting for 15 days but disappearing at one month. Tang et al. (2022) extended stimulation to fifteen sessions and observed marked reductions in pain intensity from the second week onwards, with large effect sizes, although again without evidence of durability beyond the treatment period (see Table 1).

Taken together, these findings indicate that stimulation of M1 through tDCS or rTMS can reduce cancer-related pain, but the durability of these effects is limited. Protocols involving at least five sessions of tDCS appear to provide modest persistence up to one month, whereas rTMS protocols with ten or more sessions consistently produce short-term analgesia lasting no longer than 15 days. No study demonstrated sustained efficacy beyond one month.

Quality assessmentTable 2 summarizes the critical appraisal of the included RCTs. Most studies (6/8) were conducted under double‑blind conditions, thereby reducing detection bias. Two studies did not fully meet this criterion: Goto et al. (2020) was a small pilot crossover trial conducted under single‑blind conditions (participants blinded) but without a sham control group, which limits comparability and increases risk of bias. In Hanna et al. (2023), blinding of participants and outcome assessors was not explicitly reported.

Quality assessment of RCTs.

| Goto et al., 2020 | Hanna et al., 2023 | Ibrahim et al., 2018 | Kamal et al., 2022 | Kamal et al., 2023 | Khedr et al., 2015 | Stamenkovic et al., 2020 | Tang et al., 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection and Allocation | 1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Intervention administration | 4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | Y | Unc. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| 6. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | N | Unc. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Evaluation, detection and measurement of results | 7. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 8. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 9. Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomized? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Goto et al., 2020 | Hanna et al., 2023 | Ibrahim et al., 2028 | Kamal et al., 2022 | Kamal et al., 2023 | Khedr et al., 2015 | Stamenkovic et al., 2020 | Tang et al., 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention of participants | 10. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Statistical conclusion of validity | 11. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 13. Was the trial design appropriate, and were any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Abreviaturas: N – NO; Y – YES; Unc. – Unclear.

Regarding baseline comparability, all controlled trials reported no significant differences between groups at baseline. In contrast, Goto et al. (2020) did not assess baseline comparability, as all participants received active stimulation under different parameter conditions rather than being allocated to distinct intervention and control groups.

Across the remaining domains — including identical treatment of groups aside from the intervention, completeness of follow‑up, and analysis of participants in their randomized groups — all studies met the appraisal criteria. Notably, none of the trials reported blinding of those delivering the intervention, which represents a common limitation in non‑invasive brain stimulation studies.

DiscussionDespite advances in diagnosis and treatment, which have contributed to increased survival for cancer patients, pain remains one of the most disabling side effects (Pereira, 2023). Non‑invasive brain stimulation techniques such as tDCS and rTMS have shown promise in managing pain across various conditions, but evidence in the oncological context remains limited. The studies included in this systematic review assessed diverse patient populations, cancer types, and neuromodulation protocols, yielding mixed but generally positive findings. Most studies involved patients with breast or lung cancer, and stimulation of the primary motor cortex was the most common target. Multi‑session protocols tended to report more sustained analgesic effects, whereas single‑session interventions did not achieve clinically meaningful benefit.

The methodological quality of the included studies varied, which may have influenced the interpretation of findings. While all studies used true randomization and concealed allocation, Goto et al. (2020) was a small pilot crossover trial without a sham control group, limiting comparability and increasing risk of bias. Participant blinding was generally implemented, though unclear in Hanna et al. (2023), and personnel delivering the interventions were not blinded in any study. Outcome assessors were blinded in most studies, except Goto et al. (2020) and Hanna et al. (2023, unclear).

Clinical versus statistical heterogeneityClinical heterogeneity was evident across cancer types (breast, lung, hepatocellular, gastrointestinal, hematological), stimulation sites (M1 versus insula, DLPFC), and intervention schedules (single versus multi‑session protocols). Statistical heterogeneity arose from the use of different pain assessment scales (VAS, VDS, NRS, ESAS, SF‑MPQ2, LANSS) and variable follow‑up periods (72 h to 1 year). Taken together, these differences limit comparability and reinforce the need for strictly cautious interpretation of pooled findings, particularly given the extremely small number of RCTs (n = 8).

Effects of rTMS on cancer painThree studies (Tang et al., 2022; Khedr et al., 2015; Goto et al., 2020) evaluated rTMS for pain relief in cancer patients. Tang et al. (2022) demonstrated significant reductions in lung cancer patients measured by NRS, consistent with prior evidence that stimulation of the primary motor cortex can alleviate neuropathic and chronic pain (Hirayama et al., 2006; Lefaucheur et al., 2014). Khedr et al. (2015) examined patients with heterogeneous malignant visceral pain (pancreatic, hepatocellular, gallbladder, esophageal, stomach, non‑Hodgkin’s lymphoma, mesothelioma) and found improvements in VAS and VDS, though effects were transient and not sustained beyond one month (Zang et al., 2021). Goto et al. (2020), despite lacking a sham group, reported significant decreases in P‑VAS, D‑VAS, and SF‑MPQ2 after four sessions in breast and gynecological cancer patients. These findings align with prior studies (Hirayama et al., 2006; Lefaucheur et al., 2014; Chien et al., 2023), and Chien et al. (2023) further demonstrated in a meta‑analysis that rTMS significantly reduced pain in non‑brain malignancies, whereas other forms of non‑invasive stimulation did not. Collectively, rTMS appears to induce rapid analgesia, but its durability remains limited, underscoring the need for repeated or maintenance protocols.

Effects of tDCS on cancer painFive studies (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Stamenkovic et al., 2020; Kamal et al., 2022, 2023; Hanna et al., 2023) investigated tDCS. Ibrahim et al. (2018) found that stimulation over M1 in hepatocellular carcinoma patients reduced pain measured by VAS and VDS, with reductions evident from the fifth session and maintained at one month. Stamenkovic et al. (2020) reported improvements in postoperative lung cancer patients, particularly in pain associated with coughing measured by VAS, accompanied by reduced morphine use; however, these effects were not sustained at one year. Kamal et al. (2022) showed that a single session assessed by ESAS pain score was insufficient to produce significant benefit. Kamal et al. (2023) demonstrated that repeated sessions targeting M1 or the insula reduced pain measured by VAS, VDS, and LANSS, with benefits persisting for 15 days but attenuating after one month. Hanna et al. (2023) reported a 32 % reduction in VAS after five bilateral sessions in breast cancer patients. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that tDCS may provide moderate but consistent short-term pain relief (Pinto et al., 2018; Pacheco-Barrios et al., 2020; Capetti et al., 2024). While tDCS is more portable and cost-effective than TMS (Funke, 2013), making it suitable for home-based use, its effects are not permanent and require ongoing sessions (Antal et al., 2010).

Comparative effectiveness of TMS and tDCSThe studies included in this review do not provide direct head‑to‑head comparisons between tDCS and rTMS, and therefore no clear superiority can be established. Indirect comparisons suggest that rTMS appears to yield faster but shorter‑lived analgesia, whereas tDCS may be associated with modest persistence up to one month, though evidence remains preliminary (Kamal et al., 2023; Khedr et al., 2015). Practical differences may nonetheless inform hypotheses for future research: tDCS is portable and potentially suitable for home‑based use, while rTMS requires specialized equipment but may induce more rapid effects (Funke, 2013).

Safety and feasibilityNon‑invasive neuromodulation techniques do not require a surgical procedure or trial period and can therefore be used earlier in the treatment continuum, often as part of an interdisciplinary treatment model. In addition, patients do not need a recovery time and can return to their daily lives after sessions. Disadvantages include the need for multiple sessions and the heterogeneity of stimulation protocols (Knotkova et al., 2021). Both TMS and tDCS have some adverse effects, including scalp discomfort, headaches, tingling or itching sensations. tDCS can also cause redness at electrode sites, while TMS can induce a feeling of fatigue. Despite these, studies highlight the safety of both techniques, with minimal and transient side effects in most cases, even when used for other clinical conditions (Fernandes et al., 2024). This reinforces the potential of these approaches for managing cancer pain.

LimitationsThis review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the small number of studies included limits the generalizability of the conclusions. Although a comprehensive search strategy was applied, it is possible that some relevant studies were not retrieved, as certain trials may be indexed in databases that were not accessible. Furthermore, the included studies showed a high degree of heterogeneity regarding sample size, cancer type, pain characteristics (neuropathic, visceral, acute, and chronic pain), stimulation technique, and duration of treatment. This variability made it difficult to perform direct comparisons or meta-analytical synthesis. Consequently, subgroup or sensitivity analyses were not feasible due to the limited number of trials and the methodological diversity among them. Instead, a narrative synthesis was conducted to qualitatively explore these differences, emphasizing patterns related to stimulation targets, number of sessions, and cancer types.

In addition to the limitations previously described the potential for publication bias should be considered, as small or negative studies may be underrepresented in the literature. Similarly, the inclusion of studies only in English, Portuguese, and Spanish introduces a possible language bias, which may have excluded relevant evidence published in other languages.

Additionally, methodological limitations—such as lack of blinding of personnel, baseline imbalances, and unclear participant blinding in some studies—may have influenced reported outcomes, emphasizing the need to interpret the results with caution. Finally, most studies assessed only short-term outcomes (from a single session up to a few weeks), limiting evidence for long-term sustainability of analgesic effects and broader clinical applicability.

As a future perspective, multicenter studies with larger, more homogeneous samples and standardized stimulation parameters are warranted to better determine the optimal protocols and long-term effectiveness of tDCS and rTMS in cancer pain management.

ConclusionIn conclusion, preliminary evidence suggests that both rTMS and tDCS may have potential as non‑pharmacological methods for managing cancer pain. Indirect evidence suggests that rTMS appears to induce faster but short‑lived analgesia, while tDCS may be associated with modest persistence up to one month when delivered in repeated sessions. However, the current evidence remains preliminary, with most studies limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous stimulation protocols, diverse cancer types, and short‑term follow‑up. Future studies should aim to refine stimulation parameters, perform direct comparisons between rTMS and tDCS, and investigate how these neuromodulations methods can be integrated with pharmacological and behavioral strategies to improve their long‑term effectiveness. Multicenter, adequately powered randomized controlled trials with standardized protocols and extended follow‑up periods will be essential to confirm efficacy, optimize clinical application, and ensure sustainable pain relief in cancer patients.

Funding informationThis work was supported by Portucalense University

FundingThis article was supported by National Funds through FCT Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within RISE-Health, R&D Unit (reference UID/06397/2023).

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Sara M. Fernandes reports financial support and article publishing charges were provided by Prince Henry Portucalense University Department of Psychology and Education. Sara M. Fernandes reports a relationship with Prince Henry Portucalense University Department of Psychology and Education that includes: employment. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.