Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoThe disclosure of breast biopsy results, whether indicating cancer (positive) or not (negative), can be experienced as a psychologically distressing event and could involve perceived threat to life. As peritraumatic distress is a predictor of post-event psychological symptoms, its investigation in the context of breast cancer screening could improve early identification of individuals at risk for persistent distress. This study first examined the proportion of individuals exceeding the clinical threshold for post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and non-specific distress (DT) at 7 days and 1-month post-biopsy results. It then tested whether peritraumatic distress experienced at the time of the result disclosure predicted PTSS and DT at both timepoints. An exploratory objective assessed whether perceived life threat at disclosure predicted distress outcomes differently based on biopsy results. In a sample of 191 participants, 85.9% exceeded the PTSS threshold at 7 days and 73.6% at 1 month. In contrast, 12.3% exceeded the DT threshold at 7 days, and 8.5% at 1 month. Peritraumatic distress significantly predicted PTSS at 7 days (B = 0.44, SE = 0.16, t = 2.80, p = .006) and 1 month (B = 0.76, SE = 0.18, t = 4.26, p < .001), and DT at only 7 days (B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, t = 2.60, p = .010), regardless of diagnosis outcome. Exploratory analyses showed that perceived life threat at disclosure predicted PTSS at both timepoints, only among individuals with negative results (B = 6.59, SE = 2.03, 95% CI [2.58, 10.59], p < .001). These findings highlight that the screening process itself can be perceived as life-threatening, and that assessing peritraumatic distress at the time of biopsy results may help prevent lasting symptoms, even without a cancer diagnosis.

Breast cancer screening has become a routine part of healthcare for women worldwide, with millions undergoing mammography each year (Siegel et al., 2024). Yet, for 5–10 % of these women, screening is just the beginning of the oncological trajectory, as they face the additional challenge of a biopsy, an intrusive procedure involving the sampling of tissues or cells from the breasts and/or armpits for further examination (Zagouri et al., 2008). Biopsy is the only screening method that definitively diagnoses breast cancer (American Cancer Society, 2015) and can cause physical pain, infection, and scarring (Miller et al., 2014). Given its closeness to the possibility of a breast cancer diagnosis, undergoing a biopsy can lead to heightened psychological distress compared to alternative screening methods (Iwamitsu et al., 2005; Kamath et al., 2012). The diagnosis phase is marked by the announcement of screening test results, which corresponds to the clinical diagnosis (Cedolini et al., 2014). More specifically, a breast cancer diagnosis indicates the presence of cancerous cells and the continuation throughout the breast cancer trajectory, while negative biopsy results indicate the absence of cancer with or without non-cancerous breast conditions (American Cancer Society, 2015).

Receiving a potentially life-threatening diagnosis of breast cancer has been shown to trigger or increase severe symptoms of psychological distress in more than a third of patients, which may alter the psychological impact of medical events and distress experiences (Fortin et al., 2021). However, it is important to recognize that the perception of threat is highly subjective, which means that what may be perceived as traumatic for one individual may not be the same for another depending, among other factors, on their personal cognitive appraisal of the situation (Cordova et al., 2017). This subjectivity, rather than the cancer’s clinical stage, aligns with Criterion A of trauma in the DSM-5, which emphasizes the subjective experience of danger (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). While a positive biopsy result was previously recognized as a life-threatening event in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994), it is no longer identified as such in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). This shift has created a debate regarding the classification of a breast cancer diagnosis as a traumatic event, as some clinicians and researchers continue to reference the DSM-IV while others do not acknowledge a cancer diagnosis as a traumatic event (Cordova et al., 2017; Kangas et al., 2002).

Oncology settings often rely on the Distress Thermometer (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003; Ownby, 2019) throughout the care trajectory to briefly screen for non-specific distress, a broad construct referring to general emotional strain, worry, or somatic discomfort that may not meet clinical thresholds for anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) but can still interfere with daily functioning (Kessler et al., 2002). This single-question screening measure, which asks patients to rate their distress level on a scale of 0 to 10, is commonly used due to time constraints and the influence of American guidelines (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003; Ownby, 2019). However, this approach does not provide a comprehensive assessment of psychological distress or trauma-related processes and may overlook other critical symptoms potentially leaving unresolved issues that can interfere with patients’ emotional recovery and overall quality of life. Among the various symptoms of psychological distress observed in this population, PTSS often appear immediately following the breast cancer diagnosis (Fortin et al., 2021) and typically resolve over time for many individuals. Assessing early PTSS during the first week after result disclosure is clinically relevant, as acute distress at this stage has been shown to predict the chronicity and intensity of subsequent trauma symptoms (Bryant, 2003). Identifying these early responses may therefore guide preventive interventions before symptoms become chronic. However, a subset of patients will experience persistent PTSS beyond the one-month criterion for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e.g., Arnaboldi et al., 2017). While not all patients will experience severe PTSS, some may not present any distress, or may encounter forms of psychological distress that fall below clinical thresholds, allowing them to navigate the challenges associated with the breast cancer trajectory with less impact on their mental health. In contrast, for those who experience more debilitating levels of distress, PTSD can develop, characterized by severe symptoms of avoidance, hyperarousal, and reexperiencing the trauma (APA, 2013; French-Rosas et al., 2011). These symptoms can lead to a deterioration in overall patient condition, affecting health-related quality of life, reducing adherence, decreasing satisfaction with received care, and in some cases, potentially reducing cancer survival chances (Howell & Olsen, 2011; Brown et al., 2003; Groenvold et al., 2007; Hamer et al., 2009). Identifying important predictors of PTSS is crucial, as it enables the early identification of patients who may benefit from targeted psychosocial services and emphasizes the importance of monitoring the evolution of symptoms, as they can worsen over time, regardless of a formal diagnosis.

Peritraumatic distress, the emotional and physiological upheaval experienced during or immediately after a traumatic event, is a robust predictor for the development of PTSS and has been extensively studied across various populations, both clinical and non-clinical (see meta-analysis: Thomas et al., 2012). While it has never been shown in breast cancer populations, it can be hypothesized that this experience may lead to peritraumatic distress symptoms due to the intense emotional and psychological challenges individuals face during this critical time. Some patients may even dissociate during or immediately after receiving their results, adding another layer of complexity to their emotional response (Kangas et al., 2005). Given that PTSS can emerge or worsen following biopsy results and significantly affect the breast cancer trajectory and overall quality of life (Fortin et al., 2025; Voigt et al., 2017), it is crucial to investigate this predictor within this population. In addition, because the subjective perception of a life-threat is central to Criterion A of the PTSD diagnosis, it may represent a particularly salient aspect of peritraumatic distress worth exploring in relation to PTSS, especially given the variability in how individuals cognitively appraise the threat associated with a potential cancer diagnosis. Establishing peritraumatic distress as a potential reliable predictor is pivotal for integrating targeted preventive interventions aimed at monitoring and treating PTSS at the time of receiving biopsy results. Such interventions could mitigate the impact of PTSS on physical health and psychological well-being (Dimitrov et al., 2019).

While much attention has been given to the psychological distress experienced by individuals undergoing biopsy for suspected breast cancer (see review: Montgomery & McCrone, 2010), fewer studies have specifically examined those who receive negative biopsy results and are subsequently discharged from oncological care. Research on benign breast conditions has shown that individuals who receive negative biopsy results frequently experience significant anxiety and depressive symptoms (see reviews: Woodward & Webb, 2001; Meechan et al., 2005), often at higher rates than patients diagnosed with breast cancer (Woodward & Webb, 2001). Persistent behavioral changes, such as heightened cancer worry, increased medical consultations, and intensified self-examination, have been observed even months after receiving a negative biopsy result (Montgomery & McCrone, 2010; Brewer et al., 2007), underscoring the enduring impact of the breast cancer screening experience. Although general psychological distress following biopsy procedures, regardless of whether biopsy results are positive or negative, has been well documented (e.g., Ando et al., 2011; Bai et al., 2012; Meechan et al., 2005), trauma-specific responses such as PTSS have been primarily studied in patients with positive biopsy results. Early identification of patients at risk for developing PTSS is therefore critical for enabling timely psychosocial interventions and preventing symptom chronicity. Moreover, although clinical and research attention has predominantly focused on the traumatic impact of receiving a breast cancer diagnosis, this emphasis may contribute to the assumption that patients who receive negative biopsy results are protected from PTSS. However, the fear, uncertainty, and perceived threat associated with possible abnormal findings and the biopsy procedure itself may be sufficient to trigger trauma responses, even in the absence of malignancy (Andrykowski et al., 2002; Lindberg & Wellisch, 2004). While trauma-related symptoms may arise following either positive or negative biopsy results, the confirmation of a life-threatening diagnosis could intensify these psychological responses, potentially leading to more severe and persistent trauma outcomes among individuals diagnosed with cancer.

Objectives and hypothesesThis study primary aims to describe the proportion of patients exceeding the clinical threshold for PTSS symptoms and non-specific distress at both 7 days (acute phase) and 1 month (timepoint for PTSD diagnosis). The second objective is to determine whether peritraumatic distress experienced at the time of biopsy results disclosure (whether positive or negative) is a reliable predictor of self-reported PTSS and non-specific distress at 7 days and 1 month following the announcement, with the type of biopsy results serving as a moderator. We hypothesized that the total scores of peritraumatic distress measured at the time of the biopsy results announcement would predict PTSS and non-specific distress at both measurement points. We anticipated that it would be stronger in patients who received positive biopsy results compared to those who received negative biopsy results. Finally, an exploratory objective of the study is to assess whether perceived life threat specifically predicts PTSS at 7 days and 1 month following the announcement and if the type of biopsy results (positive or negative) moderates this effect.

MethodsThe present study is part of a larger longitudinal study aimed at investigating the biopsychological predictors of psychological distress and quality of life among individuals who receive either positive or negative biopsy results. However, only the tools and information pertinent to this paper are discussed, as other measures used in the broader study are beyond the scope of the current analysis. Ethics approval was obtained from the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux (CIUSSS) de l’Est-de-l’Île-de-Montréal (CEMTL-2024–3378).

ParticipantsParticipants were recruited from June 2023 to October 2024 in collaboration with medical staff (oncologists and nurse) during the screening phase for suspected breast cancer at the specialized Breast Clinic of Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital. The participants were either met by a research team member in a consultation room after having received a brochure informing them about the study or contacted by phone if they communicated an interest for the study to their medical team. To be included in the study, participants needed to meet the following criteria: (i) be aged 18 and above; (ii) have been prescribed a biopsy or are awaiting the results of their biopsy; (iii) must understand spoken and written French; (iv) have provided personally signed informed consent indicating that they have been informed of all relevant aspects of the study and consent to participate. Exclusion criteria were: (i) being diagnosed with other types of cancer (assessed by collaborating oncologists); (ii) confirmed suicidal risk by the medical team; (iii) presence of self-reported severe psychopathologies and conditions (e.g., dementia) that may affect the ability to consent.

MeasuresNon-specific distressThe Distress Thermometer (DT; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003) is a validated questionnaire administered in clinical and research settings specifically for patients diagnosed with cancer (Ownby, 2019). The questionnaire helps identify the severity of psychological distress at critical times, such as after diagnosis and during subsequent medical appointments. The tool consists of a single question, asking patients to rate their level of distress over the past seven days on a scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). Most studies use a score of 6 as being clinically significant (Abu-Odah et al., 2023). The DT was completed by participants at baseline (i.e., at biopsy prescription), 7 days and 1 month following the biopsy results announcement. The instrument has been validated in French (Donovan et al., 2014).

Post-traumatic stress symptomsThe participants’ PTSS were measured using the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1996). This instrument is a self-reported questionnaire that assesses subjective distress associated with a traumatic event. It consists of 22 questions based on the DSM-IV criteria for diagnosing PTSD, which includes three subscales: intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal reflecting different aspects of PTSS (APA, 2013). In comparison to the DSM-IV, the DSM-5 has more symptoms and divided the criteria for avoidance and numbing in two distinct subscales of symptoms. However, this revision does not fundamentally alter the phenotype of PTSD, and the IES-R continues to be useful for screening PTSS (Gnanavel & Robert, 2013). Items are rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). A score of 34 indicates clinically chronic distress symptoms (Orsillo, 2002). The instrument was completed by participants at baseline (i.e., at biopsy prescription), 7 days and 1 month following the biopsy results announcement. At baseline, participants were instructed to evaluate their symptoms in relation to the anticipated biopsy results (i.e., the potential diagnosis of breast cancer). At 7 days and 1 month, they were instructed to evaluate their symptoms in relation to the actual biopsy results announcement. This instruction was explicitly provided in the questionnaire. The instrument has been validated in French (Brunet et al., 2003).

Peritraumatic distressThe Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) is an instrument designed to assess an individual’s level of peritraumatic distress during or following a traumatic event (Brunet et al., 2001). The questionnaire is self-reported and consists of 13 items rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 5 (extremely true) (Brunet et al., 2001). The item 1 (i.e., I thought I might die during the event) captures the perception of immediate threat to life, which is a key aspect of peritraumatic distress. The questionnaire was administered within 24 h following the biopsy results announcement to ensure the validity of the dissociation measure. The reference traumatic event was the biopsy results announcement, and this instruction was explicitly provided in the questionnaire. The instrument has been validated in French (Jehel et al., 2005).

Breast cancer diagnosis confirmationThe biopsy results (positive or negative) were confirmed by consulting the report available in the participants’ medical records. This variable was added as a moderator based on evidence suggesting that receiving a cancer diagnosis may alter the psychological impact of medical events and distress experiences (Fortin et al., 2021).

DissociationThe Peritraumatic Dissociative Experience Questionnaire (PDEQ-10SRV) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that assesses dissociative experiences occurring during a highly stressful or traumatic event within the minutes and hours following it (Marmar et al., 1994). Participants rate, on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (extremely true), the degree of depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, out-of-body experiences, altered perception of time, and body image. The PDEQ-10SRV was administered once, 24 h within the biopsy results announcement. A score above 15 was used as the cut-off to indicate clinically significant dissociative experiences, consistent with prior research (Birmes et al., 2005). The questionnaire has been validated in French (Birmes et al., 2005). This variable was included as a covariate, given that peritraumatic dissociation is a well-documented predictor of PTSS and may amplify the impact of peritraumatic distress on later psychological outcomes.

Procedures and timelineAfter providing informed consent at the time of biopsy prescription, participants were asked to complete the first set of questionnaires, which were either emailed to them or provided in a paper format according to their preference. In this baseline questionnaire (T1), sociodemographic questions were collected before the biopsy results appointment (see Table 1 for delay in days between biopsy prescription and results). Subsequently, the second set of questionnaires (T2), including the PDI and the PDEQ-10SRV, was sent to participants at the exact time of their biopsy results appointment. Participants were asked to fill out these questionnaires within 24 h. Following the results appointment, biopsy results (positive or negative) were confirmed by the research team via the participants’ records accessible on the hospital’s online platform. Finally, the IES-R was sent to participants at 7 days (T3) and 1-month (T4) post-biopsy results. Participants had the choice to complete the questionnaire online or on paper. All online questionnaires were sent via a link created by the Qualtrics platform. Paper questionnaires were collected from the participant’s home and manually added to the database by a first member of the research team and double-checked by a second team member.

Statistical analysesStatistical analyses were performed using R software, version 12.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing); p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Preliminary analysesPreliminary analyses were conducted to describe the sample and examine the distribution of PTSS (IES-R) and non-specific distress (DT) at 7 days and at 1-month post-biopsy results. Covariates, including age, country of origin, annual income and consultation with a mental health professional at baseline, as well as dissociation within 24 h following the diagnosis, were selected based on their theoretical relevance and preliminary analyses testing their associations with the outcomes (at 7 days and 1 month). Covariates showing a significant association with the outcome at either of the two time points were included in the models. For the models predicting PTSS, the following covariates were included: age (7 days: r(190) = −0.15, p = .044; 1 month: r(187) = 0.03, p = .701), country of origin (7 days: F(6, 184) = 2.87, p = .011; 1 month: F(6, 181) = 3.70, p = .002), annual income (7 days: r(188) = −0.03, p = .680; 1 month: r(185) = −0.15, p = .047), prior mental health consultation (7 days: t(21.74) = −2.27, p = .033; 1 month: t(18.32) = −0.10, p = .923), peritraumatic dissociation (7 days: r(186) = 0.60, p < .001; 1 month: r(180) = 0.59, p < .001), and baseline PTSS (7 days: r(183) = 0.72, p < .001; 1 month: r(180) = 0.56, p < .001). For the models predicting non-specific distress, country of origin (7 days: F(6, 188) = 2.79, p = .013; 1 month: F(6, 177) = 2.19, p = .047), peritraumatic dissociation (7 days: r(190) = 0.43, p < .001; 1 month: r(177) = 0.40, p < .001) and baseline non-specific distress (7 days: r(192) = 0.48, p < .001; 1 month: r(182) = 0.39, p < .001) were retained.

Descriptives analysesThe data included assessments categorized into four levels for PTSS: Subclinical (scores of 23 or lower), Moderate (scores between 24 and 32), High (scores between 33 and 38), and Extreme (scores of 39 or higher). Data for non-specific distress were categorized by the cut-off score of ≥5 indicating clinically significant distress. For both outcomes, the number of participants (n) and corresponding percentages were calculated at each time point. Additionally, group comparisons were performed between participants with positive or negative biopsy results on the main outcome variables using independent samples t-tests.

Main analysesFour multiple linear regressions were conducted to examine the associations between peritraumatic distress (PDI) and two psychological outcomes: PTSS (IES-R) and non-specific distress (DT), assessed at 7 days and 1-month post-biopsy results. The biopsy result was included as a moderator. For each outcome (PTSS and DT), separate models were estimated at 7 days and at 1 month, yielding a total of four models. Covariates identified in preliminary analyses were included the respective models.

Exploratory analysesFour multiple linear regressions were performed to examine whether perceived life threat (assessed with a single item from the PDI) was associated with PTSS and DT. The biopsy result was included as a moderator. Each outcome (PTSS and DT) was analyzed separately at 7 days and at 1 month, yielding four distinct models. The same covariates identified for each outcome in the preliminary analyses were included in the respective models.

ResultsPreliminary analyses: description of participants and clinical variablesThe sample was composed of 191 patients, whose characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the total sample, 159 participants (85.9 %) at 7 days post-biopsy results and 137 (73.6 %) at 1 month exceeded the clinical threshold for PTSS. At 7 days, 38.9 % of participants reported extreme PTSS levels, 28.6 % high, 18.4 % moderate, and 14.1 % subclinical. At 1 month, 33 % of participants were in the extreme range, 30.2 % high, 13.4 % moderate, and 23.5 % subclinical. Regarding non-specific psychological distress, 20 participants (12.3 %) exceeded the clinical threshold at 7 days, and 15 (8.5 %) at 1 month. Most of the sample fell within the subclinical range at both timepoints (87.7 % and 91.5 %, respectively). Peritraumatic dissociation (PDEQ > 15), assessed within 24 h of the results disclosure, was reported by 10.4 % of participants who received a positive biopsy result and 5.3 % of those who received a negative result.

Descriptive variables of the sample (n = 191).

Note. *p<.05 (significant group difference); N/A: Non applicable; PDEQ: The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experience Questionnaire; PDI: Peritraumatic Distress Inventory; PTSS: Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms; DT: Distress Thermometer; IES-R: Impact Event Scale-Revised.Max. Int.: Maximum intensity in arbitrary unit.

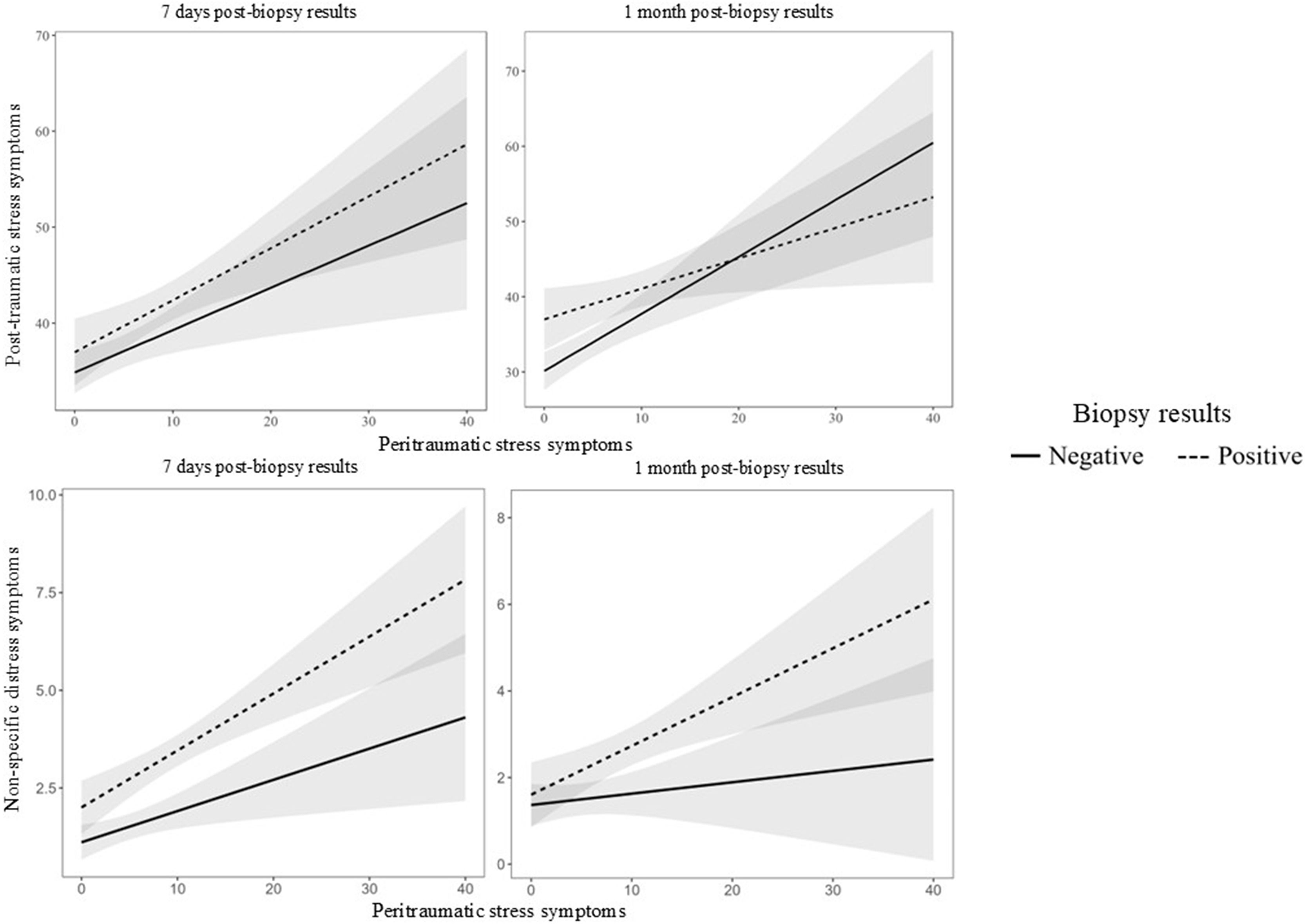

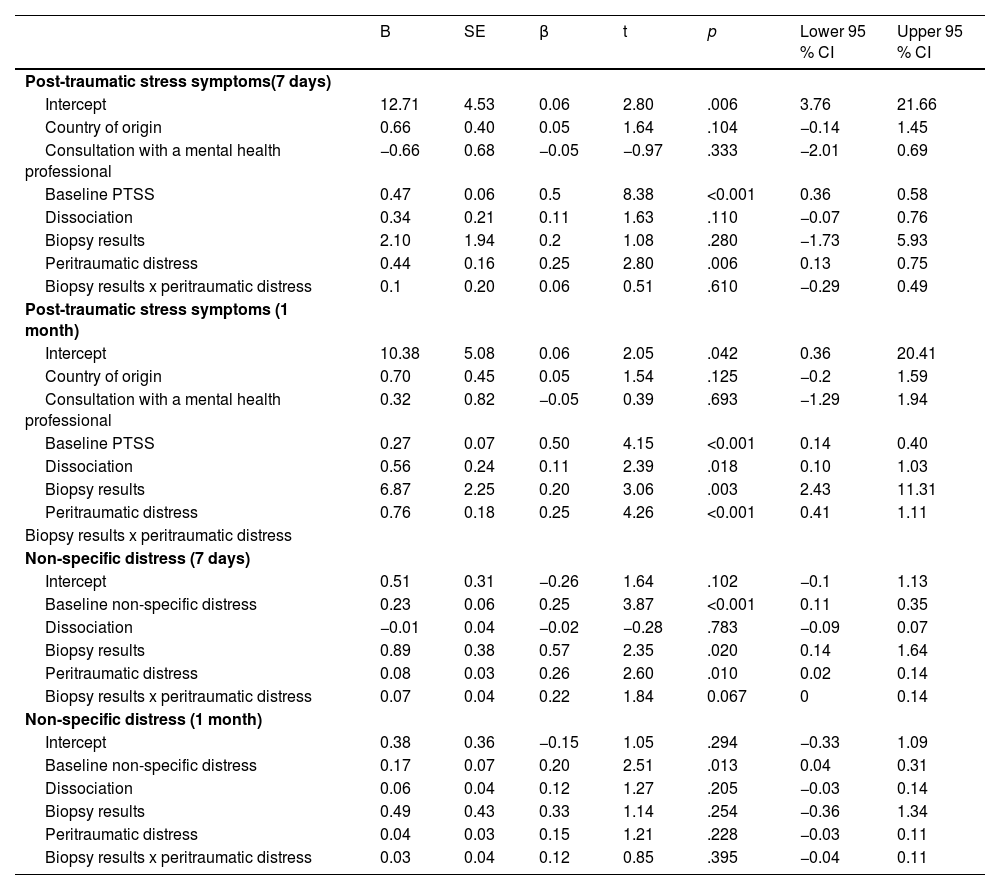

PTSS: The multiple linear regressions revealed that PDI scores were positively associated with PTSS at 7 days (B = 0.44, SE = 0.16, t = 2.80, p = .006) and 1 month (B = 0.76, SE = 0.18, t = 4.26, p < .001) following the biopsy results. At 1 month, diagnosis status showed a significant main effect (B = 6.87, SE = 2.25, t = 3.06, p = .003), with pairwise comparisons indicating that participants who received a positive biopsy result reported higher PTSS scores compared to those who received a negative result (estimated difference = –4.48, SE = 1.69, t = –2.65, p = .009). However, the interaction between PDI and diagnosis status was not significant at either time point (7 days: B = 0.10, SE = 0.29, t = 0.51, p = .610; 1 month: B = –0.35, SE = 0.21, t = –1.65, p = .100), suggesting that the association between peritraumatic distress and PTSS did not differ between diagnosis groups. See Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Predictors and covariates associated with PTSS and non-specific distress at 7 days and 1-month post-biopsy results.

Notes. PTSS: Post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Non-specific distress: The multiple linear regressions revealed that PDI scores were positively associated with DT scores at 7 days (B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, t = 2.60, p = .010), but not at 1 month (B = 0.04, SE = 0.03, t = 1.21, p = .228) following the biopsy results. At 7 days, diagnosis status showed a significant main effect (B = 0.89, SE = 0.38, t = 2.35, p = .020), with pairwise comparisons indicating that participants who received a positive biopsy result reported higher DT scores compared to those who received a negative result (estimated difference = –1.34, SE = 0.28, t = –4.73, p < .001). However, the interaction between PDI and diagnosis status was not significant at both time point (7 days: B = 0.07, SE = 0.04, t = 1.84, p = .067; 1 month: B = 0.03, SE = 0.04, t = 0.85, p = .395), indicating that the relationship between PDI and DT did not differ across diagnosis groups. See Table 2 and Fig. 1.

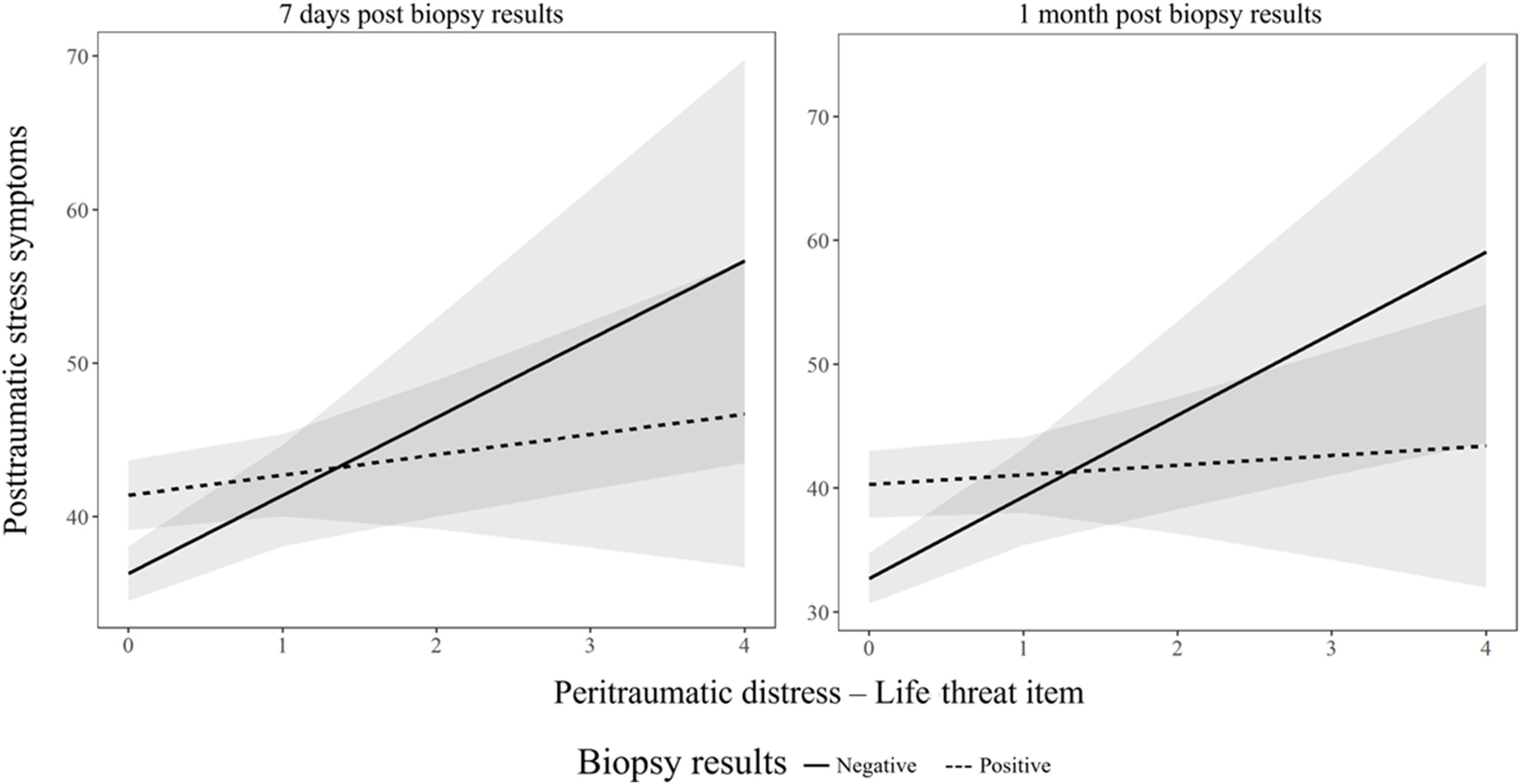

Exploratory analysesPTSS: Perceived life-threat scores were significantly positively associated with PTSS scores at both 7 days (B = 5.09, SE = 1.74, t = 2.93, p = .004) and 1 month (B = 6.59, SE = 2.03, t = 3.25, p = .001) following the biopsy results. Diagnosis status showed a significant main effect at both time points (7 days: B = 5.10, SE = 1.49, t = 3.43, p < .001; 1 month: B = 7.59, SE = 1.74, t = 4.37, p < .001), where participants who received a positive biopsy result reported higher PTSS scores compared to those who received a negative result (7 days: estimated difference = –4.08, SE = 1.41, t = –2.91, p = .004; 1 month: estimated difference = –6.01, SE = 1.64, t = –3.66, p < .001). However, the interaction between the life-threat item and the biopsy results was only significant at 1 month (B = −5.81, SE = 2.52, t = −2.31, p = .022), but not at 7 days (B = −3.77, SE = 2.17, t = −1.74, p = .084). Simple slopes analyses revealed that the association between perceived life-threat and PTSS was significant only for those with negative biopsy results (B = 6.59, SE = 2.03, 95 % CI [2.58, 10.59], p < .001), but not for those with positive biopsy results B = 0.78, SE = 1.58, 95 % CI [−2.34, 3.90], p = .620). See Table S1 and Fig. 2.

Non-specific distress: Perceived life threat was not associated with DT at either 7 days (B = −0.17, SE = 0.37, t = −0.47, p = .638) or 1 month (B = −0.18, SE = 0.40, t = −0.45, p = .651). Diagnosis status showed a significant main effect at both 7 days (B = 1.56, SE = 0.30, t = 5.19, p < .001) and 1 month (B = 0.92, SE = 0.33, t = 2.80, p = .006), where participants who received a positive biopsy result reported higher DT scores compared to those who received a negative result (7 days: estimated difference = –1.73, SE = 0.28, t = –6.12, p < .001; 1 month: estimated difference = –0.96, SE = 0.31, t = –3.11, p = .002). The interaction between the life threat item and the type of biopsy result was non-significant (7 days: B = 0.62, SE = 0.43, t = 1.42, p = .156; 1 month: B = 0.14, SE = 0.47, t = 0.30, p = .763), suggesting that the biopsy results did not moderate the relationship between perceived life-threat and DT. See Table S1.

DiscussionThis study sought to examine the proportion of patients exceeding the clinical threshold for PTSS and non-specific distress at both 7 days (acute phase) and 1 month (a critical timepoint for PTSD diagnosis) post-biopsy results. One of the key goals was to explore whether peritraumatic distress at the time of biopsy results disclosure could reliably predict self-reported PTSS and non-specific distress at these two timepoints, with the type of biopsy results acting as a moderator. Lastly, the study aimed to explore whether perceived life threat serves as a specific predictor of PTSS, and whether the type of biopsy results (positive or negative) moderates this relationship, independent of the time points.

The results indicate that PTSS remain severe even beyond the acute phrase, with 85.9 % of the sample exceeding the clinical threshold at 7 days and 73.6 % at 1-month post-biopsy results (positive or negative), potentially meeting criteria for PTSD diagnosis. In contrast, non-specific psychological distress levels were lower, with 12.3 % of participants at 7 days and 8.5 % at 1 month exceeding the clinical threshold. This discrepancy highlights the added clinical value of PTSS assessment both in term of sensitivity (capturing larger portion of distressed individuals) and nuance of clinical manifestations. PTSS encompass a specific set of cognitive, emotional, and physiological symptoms that can significantly impair quality of life and interfere with medical care adherence (e.g., Shelby et al., 2008; Nipp et al., 2018; Springer et al., 2023), whereas tools like the DT relies on a less specific single item (Ownby, 2019; Sun et al., 2022). Although time-efficient and convenient for capturing non-specific distress in clinical settings, it assesses fewer dimensions of psychological distress. As a result, patients may find it difficult to operationalize what “distress” means, whereas PTSS measures offer multiple concrete symptom examples throughout several items which can enhance clarity and support more nuanced assessment. This distinction is particularly important because many participants presenting moderate to extreme PTSS levels would not have been identified as distressed based on DT alone, thereby falling through the cracks of standard psychosocial screening. Moreover, current guidelines tend to indicate that only individuals diagnosed with breast cancer should benefit from psychosocial services in North American medical settings (see guidelines: Riba et al., 2023; Hewitt et al., 2004). However, the present findings suggest that not receiving a diagnosis can also result in moderate to extreme PTSS and/or non-specific distress in a large proportion of patients. As a result, many individuals in need of psychosocial support may remain unidentified and untreated.

Regarding the second objective, the first hypothesis was confirmed as peritraumatic distress proved to be a predictor of PTSS at 7 days and at 1 month following the biopsy results, while it was a predictor of non-specific distress only during the acute phase in our sample. The second hypothesis, that the association between peritraumatic distress and PTSS and non-specific distress would vary based on the type of biopsy results was not supported. This finding reinforces the importance of considering the entire diagnosis process, rather than just the outcome, as a potential source of psychological impact. While diagnosis results differ across individuals, undergoing a biopsy is the one medically shared experience within the sample, and may represent a pivotal moment when the perception of life-threat becomes more concrete (Andrykowski et al., 2002; Montgomory, 2010). Importantly, it is not necessarily the objective confirmation of cancer that drives posttraumatic stress responses, but rather the subjective experience of life-threat, a core feature of peritraumatic distress and a key component in PTSD development (see review and model: Edmonston, 2014; Moss et al., 2020). Although psychological distress may begin earlier, such as upon discovering a lump or receiving an abnormal mammogram, the biopsy often marks the first formal medical validation of a serious concern, which could amplify emotional and physiological responses (Edmonston, 2014; Andrykowski et al., 2002; Montgomory, 2010). For some patients, these peritraumatic reactions may persist even after the breast biopsy, highlighting the need to consider trauma-informed care approaches throughout the breast cancer trajectory.

The exploratory objective of the present study was to examine whether the life threat item related to the disclosure of biopsy results could predict PTSS and non-specific distress, and whether the type of biopsy results (positive or negative) moderates this relationship. The results indicated that the PDI life threat item was a significant predictor of PTSS, but not non-specific distress, and only among participants who received a negative biopsy result. This could potentially be explained with the Cognitive Behavioral Model of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). According to this model, PTSS are maintained by a sense of current threat, which is influenced by how the trauma is processed and appraised (Brewin & Holmes, 2003; Ehlers & Clark, 2000). When individuals receive a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer, it can reduce uncertainty and perceived threat, as they have a concrete understanding of their situation and can plan accordingly. This could potentially lower anxiety and reduce the risk of developing PTSS (Liao et al., 2008). On the other hand, those with ambiguous or benign results may continue to experience heightened uncertainty and perceived threat, as they do not have clear closure, particularly if they continue to experience symptoms or health concerns that prompted the biopsy in the first place. This ongoing uncertainty could exacerbate PTSS (Oglesby et al., 2016), as they may not receive the same level of attention and support as those with a confirmed diagnosis (Guray & Sahin, 2006), leaving them to potentially cope with their mental health alone. The present findings indicate that PTSS and non-specific distress remained elevated up to one-month post-biopsy, including among participants who received a benign result, suggesting that the psychological impact of uncertainty in this context may not diminishes over time. Recognizing the profound psychological impact of perceiving a life-threatening condition, including both the biopsy procedure and the anticipation of its results, highlights the need to ensure a more equitable and comprehensive approach to mental health care within medical teams working with individuals with suspected breast cancer. Furthermore, these findings align with Rustad et al. (2012), who argued that the DSM-IV conceptualization of cancer as a potentially traumatic event better accounts for PTSS than general psychological distress models. Our results extend this perspective by showing that the perception of life threat, only for individuals with a negative diagnosis, can mirror the psychological impact typically associated with trauma. This finding is challenging current diagnosis boundaries and broadening our understanding of what constitutes a traumatic medical experience, while highlighting the importance of individual perception in shaping psychological outcome.

Building on these results, appropriate support (including psychoeducation, referral options and psychosocial services) should be offered to all individuals who have undergone a breast cancer biopsy and exhibit high levels of peritraumatic distress following their results appointment, regardless of the diagnosis outcome. Indeed, following positive biopsy results, some patients can gain access to follow-up psychosocial care and services aimed at managing these symptoms, which can help improve mental and physical health during the treatment phase and thereafter (Andersen et al., 2007). In contrast, individuals receiving negative biopsy results can face challenges in addressing lingering symptoms as they seek necessary support (Montgomery & McCrone, 2010). One of these challenges is that they are not as frequently integrated into medical settings as patients diagnosed with breast cancer (Guray & Sahin, 2006), which may result in an absence of psychological follow-up and a risk of losing track of their emotional well-being over time. Typically, the treatment approach for negative biopsy results with benign conditions involves surgical removal if necessary or regular monitoring through follow-up visits and imaging to detect any changes or developments (Guray & Sahin, 2006). For patients receiving a negative biopsy result with no breast condition, the expectation is often to resume normal life with the possibility of follow-up appointments (Montgomery & McCrone, 2010). Since many patients with suspected breast cancer undergo screening and invasive medical procedures such as the biopsy, medical settings should evaluate not only non-specific distress (often measured with a single question from the Distress Thermometer or not evaluated consistently after biopsy results; Granek et al., 2019; Holland et al., 2010), but also peritraumatic distress. This approach could help identify individuals in need of a follow-up in the month following their results, potentially mitigating PTSS regardless of biopsy outcomes. This also emphasises the impact of negative biopsy results, which despite appearing benign, can leave a significant psychological imprint lasting at least for one month.

This study has some limitations including the fact that data were collected from a single clinical site, which may reflect certain local organizational practices; however, the psychological mechanisms under study are likely relevant across settings. Also, the hospital where participants were recruited treats patients who do not speak and/or understand French, potentially excluding the experiences of some patients from the study.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study provides important insights into the early psychological processes following breast biopsy in the context of cancer screening. First, our findings support that peritraumatic distress is a significant predictor of both PTSS and non-specific distress up to one month after biopsy results, regardless of whether it was positive or negative. This emphasizes the critical role of acute emotional responses during the diagnosis phase in shaping subsequent psychological outcomes, beyond the diagnosis outcome itself. Second, while the subjective perception of life threat predicted PTSS among individuals receiving negative biopsy results, this association was not observed among those with positive diagnoses. This nuanced pattern suggests that distinct psychological mechanisms may underlie PTSS depending on biopsy results, and underscores the need for early, tailored interventions targeting emotional responses at the time of diagnosis disclosure. By identifying predictors of early PTSS, our results contribute to refining psychosocial screening strategies and improving support for patients navigating the uncertainty and emotional impact of cancer screening procedures.

FundingThis study received a research grant from the Research Center of the Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal (Montréal, Québec, Canada).

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Catherine Laurin-Bérard, Dr. Geneviève Tondreau, Dr. Marie-Claude Raymond, Dr. Sofia Bouanane, Dr. Laura My Chi Tran, and Dr. Marie-Pier Brizard for their collaboration in discussing the study with their patients. Our sincere thanks go to all the participants who generously agreed to take part in this research. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal, which provided a pilot grant for this study. Justine Fortin gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) through a doctoral scholarship. Alexe Bilodeau-Houle also acknowledges the support of a postdoctoral research scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Marie-France Marin also acknowledges support provided through her Canada Research Chair on Hormonal Modulation of Cognitive and Emotional Functions.