Edited by: Dr. Ana Rita Silva

(University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal)

Dr. Elodie Bertrand

(Paris Cité University, Paris, France)

Dr. Maria Schubert

(Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Zurich, Switzerland)

Last update: October 2025

More infoThis research examined the short-term and long-term effects of group dancing on self-esteem, depression, and self-judgment in older women participating in the GILA Methodology, a movement and performance art initiative specifically designed for mature women, developed by Galit Liss. The study, conducted from 2019 to 2023, involved 152 dancer participants (mean age 69.98 ± 5.68) who participated in one to five measurements and were categorized as either Experienced (having participated for more than ten months and performed a solo dance) or Beginner dancers. Self-reported measures of depressive symptoms, self-judgment, and self-esteem were collected. This study found that Experienced dancers showed higher self-esteem and lower self-judgment than Beginners, with no difference in depression levels (n = 152). Over two years, depression levels decreased significantly overall (n = 23). This decrease in depression was primarily observed in Experienced dancers. The depression levels of beginner dancers did not change. Over two years, they experienced a notable reduction in self-judgment, eventually reaching the same levels as experienced dancers. Initial self-judgment predicted changes in depression levels after two years, an association that was moderated by self-esteem; specifically, higher self-esteem mitigated the effect of self-judgment on changes in depression. We highlight the program's emphasis on utilizing the body's abilities, promoting acceptance, and building resilience through performance experiences. Given its limitation as an uncontrolled ecological longitudinal study, potentially affected by historical events and dependent on self-reported data, we suggest further replicating the current study.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), healthy aging is more than merely the absence of disease; it involves a holistic approach to developing and maintaining the functional ability that ensures well-being in older age. This concept includes physical, social, and mental health, integrating both personal and environmental factors (WHO, 2015). Interestingly, women's aging spans nearly four decades, and their life expectancy surpasses men's (WHO, 2019). A significant aspect of women's aging is the change in endocrine function. Decreasing hormone levels, like estrogen, affect not only physiological functions, such as the musculoskeletal system (Collins et al., 2019; Copeland et al., 2004), but also psychological functions, such as mood regulation and well-being (Berent-Spillson et al., 2017; Castanho et al., 2014; Dumas et al., 2012). These unique changes underscore the importance of promoting creative and diverse interventions to benefit the well-being of aging women.

A pivotal factor influencing the overall well-being of older individuals is maintaining strong self-esteem. Recent studies have shed light on how self-esteem fluctuates throughout life (Orth et al., 2010, 2012, 2019). Self-esteem follows an n-curve, rising from adolescence to middle adulthood, peaking around the age of fifty to sixty, and then remaining relatively stable until about age 60, after which it tends to decline (Orth et al., 2010, 2012, 2019). These studies also revealed that while self-esteem is often stable, it is changeable; low self-esteem will persist unless there is an effort to improve it. Furthermore, the researchers found that high self-esteem predicts success in interpersonal relationships, work, health, and overall well-being (Orth et al., 2019).

Rosenberg (1965) defines self-esteem as the extent to which a person views themself positively and as capable of achieving their goals. Another definition of self-esteem is a person's subjective evaluation of their worth (Orth & Robins, 2014). Maslow (1943) placed the need for self-esteem high in the hierarchy of needs, suggesting that fulfilling this need leads to feelings of self-confidence and a sense of value in the world. Conversely, a lack of self-esteem can result in feelings of inferiority, weakness, helplessness, and worthlessness, which, in severe cases, can lead to depression (M.J. Fennell, 2004; Sowislo & Orth, 2013).

Depression in older adults poses a higher risk for women compared to men (Girgus et al., 2017). It is marked by low mood, low self-esteem, a lack of interest in leisure and daily activities, sleep disturbances, weight changes, and difficulties concentrating (APA, 2013). In the general population, depression prevalence ranges from 8 % to 30 %, but in hospitalized patients and nursing homes, it can exceed 40 % (Curran & Loi, 2013). Among older adults, the prevalence ranges from 10 % to 20 %. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of treatment decreases with age, making it harder to recover from a depressive episode (Korten et al., 2012). In older adults, depression is linked to a higher risk of suicide, frequent psychiatric hospitalization, cognitive and functional decline, somatic complaints, and family overload (Zenebe et al., 2021). Rapid diagnosis and effective treatment can enhance quality of life, maintain optimal levels of functioning and independence, and reduce treatment costs and suicidal mortality (Avasthi & Grover, 2018).

A significant contributing factor to depression is the tendency towards negative self-judgment (Barcaccia et al., 2019; Ehret et al., 2015; Zuroff et al., 1990). Being self-judgmental refers to how a person examines their experiences subjectively. Self-judgment is a well-developed concept in mindfulness interventions, which requires cultivating an attentive capacity to stay in the present moment non-judgmentally (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). It was found that being non-judgmental, such as when practicing mindfulness, is a resilience factor in life crises, enabling better coping (Behan, 2020). Additionally, older women who practice mindfulness can attenuate ageism (Lester & Murrell, 2022). Practicing mindfulness helps individuals focus on their present experiences and reduces the likelihood of negative beliefs or critical thoughts, i.e., self-judgment. This decrease in self-judgment can, in turn, enhance self-esteem (Bajaj et al., 2016).

Negative self-judgment is an aspect of low self-esteem, which is a central vulnerability factor in the development and maintenance of depression (M.J. Fennell, 2004; Sowislo & Orth, 2013). Improving self-esteem in older individuals can be achieved through interventions such as physical activity (McAuley et al., 2000; Moral-Garcia et al., 2018), social community activity (Orth et al., 2010; Reitzes et al., 1995), and creative and artistic activities (Ching-Teng et al., 2019). The challenge involved in the creative process seems to increase one's sense of self-efficacy, which refers to what one thinks and feels capable of doing, and thus raises self-esteem (Flood & Phillips, 2007). Group dancing combines physical exercise, social community engagement, and creative artistic expression, making it an effective intervention to improve self-esteem in older adults (Coogan et al., 2021).

Dancing serves as a therapeutic tool, providing a nonverbal means of connecting with deep emotions and expressing oneself (Leventhal, 2008; Levy, 1988; Stanton, 1992). Marianne Chase, one of the pioneers of dance as a therapeutic tool, viewed movement as a form of communication that helps people realize their needs (Chaiklin, 1979; Levy, 1988). Movement therapy encourages the development of new behaviors, helps symbolically communicate hidden emotions, relieves anxiety, and serves as a tool for mind-body integration (Loman, 2005). According to the American Association of Movement Therapists, movement therapy promotes emotional, physical, social, and cognitive integration. This therapy facilitates personal growth through the interaction between the body and mind. Additionally, it improves mood and emotional regulation, enhances body image and self-esteem, and reduces signs of depression (Burgess et al., 2006; Mala et al., 2012).

Dancing has been found to enhance psychological well-being (Hopkins et al., 1990; Hui et al., 2009) in addition to its benefits on physical health (Hopkins et al., 1990; Hui et al., 2009; Shigematsu et al., 2002). A meta-analysis by Sheppard and Broughton (2020), which mainly included studies on group dancing in various populations, found many positive effects of dance on mental well-being. The findings showed that participating in dance classes facilitates social involvement, helps maintain mental well-being, increases life satisfaction, and contributes to self-acceptance (Sheppard & Broughton, 2020). As dance combines cognitive and physical-motor functions, such as synchronizing movement and music and remembering step sequences (Borhan et al., 2018), it has been found that among older adults, it increases body awareness, subjective sense of well-being, and movement control through cognitive, creative, and music strategies (Lewis et al., 2016). A dance training program has also been shown to improve women's mood, self-esteem, and well-being (Estivill, 1995). Additionally, middle-aged and older women who participated in health dance exercises reported improved quality of life, which was influenced by increased levels of self-esteem (Song & Song, 2014). Dance enables seniors to connect with movement and enjoy physical activity, thanks to the many flexible styles of dance and rhythms (Keogh et al., 2009). Studies indicate that dance can be a significant source of joy for older adults, even more so than other types of activity, such as aerobics, because dance can potentially evoke positive memories of the past (Lima & Vieira, 2007). In treating Parkinson's patients, dance is used as a non-pharmacological alternative to improve motor skills, as well as fatigue and depression (Tillman et al., 2017). A study of women who underwent dance mindfulness intervention, which emphasized non-judgment, compassionate love, and awareness of real-time experiences, found an improvement in their self-acceptance (Marich & Howell-Med, 2015). Studies have shown that brief dance interventions improve mental well-being and cognitive and physical functions in older adults, but long-term interventions have a more significant effect (Earhart, 2009).

Current researchThe current study examines the short- and long-term effects of group dance among older women on the three interactive psychological factors: self-esteem, depression, and self-judgment. Self-esteem and depression have a bidirectional influence (Michalak et al., 2011; Pinniger et al., 2012), although there seems to be more evidence that self-esteem impacts depression rather than vice versa (Orth & Robins, 2014; Sowislo & Orth, 2013). Moreover, self-esteem seems to be a mediating factor between mindfulness/self-judgment and depression (Bajaj et al., 2016; M.J. Fennell, 2004). These effects are examined in a longitudinal study of older women, comparing their participation experience in GILA, dance groups of the GILA Dance School for Movement and Stage Art for Women of Mature Age.

GILA (https://www.galitliss.com/en/) focuses on movement and performance art for mature women. It emphasizes discovering the artist within and utilizes the creative potential hidden within each and every woman. The name "Gila", which in the Hebrew language means “her age”, “joy”, and “discover”, reflects the spirit of women who choose to dance life at any age and contains the joy and discovery that contribute to a life of vitality. GILA was founded 15 years ago, and to date, it has involved over 1000 older women, producing artistic performances worldwide, as well as in professional dance festivals. The group leader is Galit Liss: choreographer, teacher, initiator, and artistic director of GILA.

GILA focuses on movement and performing arts for older women. Most women who attend the group have not previously engaged in dance in their lives, and together, they work to create an artistic space in which development and self-realization become possible in the aging body. The women participating in this workshop range in age from 62 to 84; a common thread among them is their curiosity about a deep process of body research and creative techniques. As expressed by Liss: “Without older women, there is no workshop; the initiative is for them, by them, and with them”. The work concept is based on body research and movement refinement while listening to the body's capabilities and recognizing the acceptance of the changes that occur in it. Additionally, creative processes involve observation and feedback.

The goals of GILA include fostering self-awareness, enhancing movement abilities with attention to bodily and sensory perception, and providing experiential exposure to artistic processes within the performing arts. Core principles of the GILA working method include the use of “movement anchors” that engage imagination, mental imagery, and multisensory perception; working with the body's present state; and acknowledging age-related physical limitations as a basis for developing a personal movement language. The process also involves engaging with biographical content related to the dancer's internal worlds and transforming this material for stage presentation. This is supported by an integration of artistic expression with principles of brain plasticity, combining sensory, motor, and cognitive approaches to movement work. The tools draw on somatic practices that utilize bodily sensations and internal imagery while highlighting the dynamic, bidirectional interaction between brain-based somatosensory processing and the embodied experience. Music has often served as a valuable tool in the development of the project's concept, which each dance could chose at any stage of the process. It can function as an organizing element that enables the creation of a structural framework for the choreography, supports the temporal organization of movements, and facilitates coordination. Additionally, music acted as a mnemonic aid by providing auditory cues that helped the dancers recall movement sequences. The GILA procedure is divided into two main parts. The first part focuses on movement and improvisation, allowing dancers to explore their bodies through personal movement work while cultivating awareness of the body, senses, space, and surroundings, all in conjunction with music. The second part centers on the creative process during which each dancer develops an individual solo piece based on biographical materials. This stage emphasizes the process of creation, choreographic composition, and translating personal narratives into performative expression. (For more details on the Key Principles of the GILA methodology, please see: https://www.galitliss.com/en/%D7%90%D7%99%D7%9A-%D7%94%D7%9B%D7%9C-%D7%94%D7%AA%D7%97%D7%99%D7%9C).

The groups comprise 15–25 women who gather weekly for a 2–3 hour session. Once a week, dancers are also offered the opportunity to participate in the performing team. At the end of each year, participants invite their families to view their concluding show, in which they create a personal solo dance.

Time- and history-related challenges should also receive attention. Since this is an uncontrolled ecological longitudinal study, local, world-historical, and political events may have made their mark during the study's years (2019 - 2023). To assess the raw value of GILA beyond the cosmopolitan changes that accompanied the scope of this study, we examined comparisons between fixed time frames (i.e., after two years).

Measuring time of experience, we addressed the end-of-year solo dance as a qualitative milestone. Thus, we defined women in their first year, measured before the solo performance, as "beginners", and after their solo as "experienced".

We hypothesized that GILA impacts psychological measures as follows:

- a.

Experience effect (Beginners- before solo dance vs. Experienced- after their solo dance):

There will be a difference between Experienced and Beginner dancers in terms of Self-esteem, Depression, and Self-judgment. Beginners will show lower levels of Self-esteem and higher levels of Depression and Self-judgment compared to Experienced dancers.

- b.

Time effect: A Time effect will be found following two years of dancing, showing an increase in Self-esteem and a decrease in Depression and Self-judgment levels.

- c.

Time and Experience effect: Following two years of dancing, Beginner dancers will show a larger increase in Self-esteem levels and a larger decrease in Depression and Self-judgment compared with Experienced dancers.

- d.

Self-esteem moderation model: After controlling for the initial Depression level, initial Self-esteem and Self-judgment will predict the change in Depression levels after two years, and Self-esteem will moderate the Self-judgment effect on the change in Depression levels.

The study sample consisted of 152 older female participants, dancers (mean ± SD: 69.98 ± 5.68) from Galit Liss's GILA, who participated in one to five time-point measurements from 2019 to 2023. Some dancers participated for a short period and were measured only once, while others continued for many years and were measured at several time points (1TP = 74; 2TP = 39; 3TP = 21; 4TP = 11; 5TP = 7). The dancers' Experience was considered advanced- “Experienced” if they reported participating in GILA for more than ten months and had performed a solo dance; otherwise, their experience was considered basic- “Beginners”. The complete demographic data are in Table 1 in the results section.

ProcedureDancer participants were recruited voluntarily after providing their consent following a short ad. Then, a personal phone call was made for recruitment, after which they independently filled out questionnaires sent to their email addresses. The research was conducted under the ethical approval of the institutional Ethics Committee (approval number: gcp/2020–139), which ensured adherence to ethical standards through the use of informed consent, anonymity, and non-mandatory completion requirements. Participants were asked to answer the following demographic variables: age, marital status, country of origin, education level, residence type, financial status, and months of dancing experience. Then, they were asked to fill out questionnaires measuring depressive symptoms, self-judgment, and self-esteem, among other questionnaires that were part of a larger study.

ToolsDepressive symptoms: A self-report psychological health questionnaire, PHQ-9 (Spitzer et al., 2001), was used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms (loss of pleasure, depressed mood, sleep and appetite disturbances, suicidal or worthless thoughts). The questionnaire consists of nine statements and feedback on their frequency during the past two weeks, using a scale, ranging from 0 ("not at all") to 3 ("almost every day"). The depression index is obtained after averaging the numerical values of the answers to all the items. The internal reliability between the details of the questionnaire was 0.75.

Self-judgment: An eight-item scale that examines judgment was used from the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006). The scale measures the degree of judgment towards the inner experience through self-report. The items were rated on a five-level Likert scale, where 1 indicated 'never or very rarely' and 5 indicated 'often or almost always'. An example item is "I criticize myself for having inappropriate or irrational feelings". The total judgment score is the average of the answers to all the items. A high score indicates a high degree of self-judgment. An internal reliability coefficient was calculated, and Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

Self-esteem: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (SES) was used (Rosenberg, 1965). The questionnaire measures self-worth by measuring positive and negative emotions. The items are rated on a four-level Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree. An example item is "I have a positive attitude towards myself". The total score of the self-esteem measure is the average of the answers to all the items. A high score indicates a high degree of self-esteem. An internal reliability coefficient was calculated, and Cronbach's alpha was 0.78.

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the demographic data for Beginners, Experienced, and total dancers in their first time-point measurement.

Demographic data for Beginners, experienced, and total dancers in their first time-point measurement.

Hypothesis 1. Effect of Experience. Three one-way ANOVAs with Experience level (Experienced / Beginner) as a between-effect factor were conducted to compare Self-esteem, Depression, and Self-judgment levels in their first measurement. The Experienced dancers group comprised 116 females, while the Beginner dancers group included 36 females. Levene's Test for Equality of Variances confirmed equal variance for all analyses. The results partially confirm the hypothesis: Self-esteem levels were significantly higher for Experienced, compared to Beginner dancers, F(1, 149) = 6.77, p = .01, η2p = 0.043, and Self-judgment level was significantly lower for Experienced, compared to Beginner dancers, F(1, 150) = 5.16, p = .02, η2p = 0.03. However, no significant difference in Depression levels between the Beginners and the Experienced dancers, F(1, 150) < 1. See Table 2 for the Mean and SD for Self-esteem, Depression, and Self-judgment levels for Experienced and Beginner dancers.

Mean and SD of Self-esteem (SES), Depression (PHQ-9), Self-judgment (FFMQ), and experience levels.

| Variables | Self-esteem (M ±SD) | Depression (M ±SD) | Self-judgment (M ±SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dancers | Experienced (n = 116) | 3.48 ±.371 | 1.37 ±.34 | 1.66 ±.58 |

| Beginner (n = 36) | 3.29 ±.43 | 1.41 ±.39 | 1.92 ±.65 | |

Hypothesis 2. Time effect following two years of dancing. We included 23 participants with a two-year difference between the two time-point measurements. Three repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted to assess the effect of Time on Depression, Self-judgment, and Self-esteem levels. The hypothesis was partially confirmed: We found a significant effect for Depression: F(1, 22) = 4.74, p = .04, η2p = 0.18, with lower levels after two years. However, there was no significant effects of Self-judgment: F(1, 22) = 1.82, p = .19, η2p = 0.07; and Self-esteem: F(1, 22) < 1. See Table 3 for the mean and SD of the main variables.

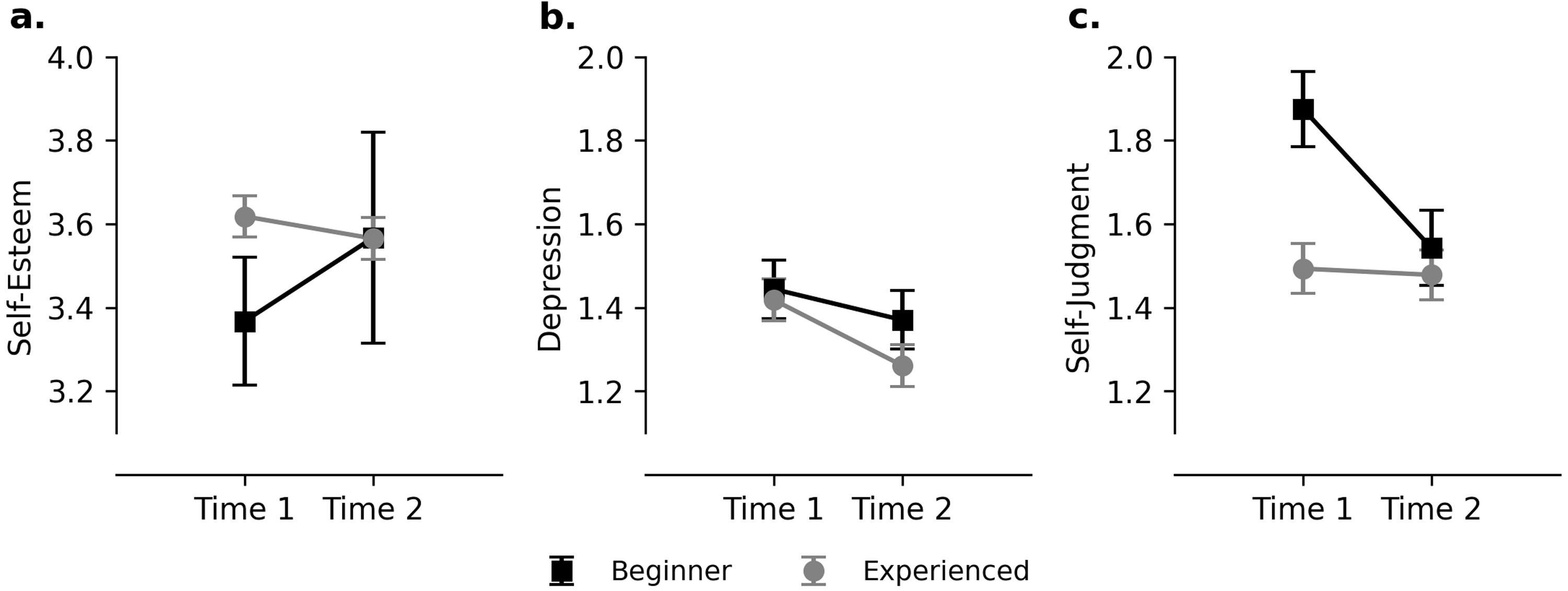

Hypothesis 3. Following two years of dancing, Beginner dancers will show a larger increase in Self-esteem levels and a larger decrease in Depression and Self-judgment compared with Experienced dancers. Three two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs with Experience level (Experienced / Beginner) as a between-effect factor and Time (Time 1 / Time 2) as a within-effect factor were conducted to compare Depression, Self-esteem, and Self-judgment levels. The Experienced dancers' group comprised 17 females, while the Beginner dancers’ group included six females. The hypothesis was partially confirmed: For Self-esteem and Depression, the interactions were not significant: F(1, 21) = 2.126, p = .16, η2p = 0.09, F(1, 21) = 0.33, p = .57, η2p = 0.004, respectively. For Self-judgment the interaction was marginally significant: F(1, 21) = 4.28, p = .051, η2p = 0.17 and the main effect of Time, F(1, 21) = 5.117, p = .034, η2p = 0.196, was significant. Since we had a theory-driven prediction, we further analysed the results with the following comparisons: Simple main effects for each Experience level and interaction between contrasts (1, −1, −1, 1). Regarding Self-esteem, we did not find any significant effect. For Depression, we only found a significant simple main effect for Experienced dancers, with lower levels of Depression in Time 2, t(21) = 2.139, p = .044, Cohen’s d = 0.518. For Self-judgment, we found a simple main effect of Time for Beginner dancers with lower levels of Self-judgment in Time 2, t(21) = 2.52, p = .02, Cohen’s d = 0.731, and a marginally significant interaction between contrasts, t(21) = 2.071, p = .051, Cohen’s d = 0.699, with larger improvement in Self-judgment for Beginner dancers compared with Experienced dancers. Note that Levene's Test for Equality of Variances showed that the variance of Self-esteem and Self-judgment in Time 1 was not equal, p = .04 and p = .01, respectively. Both tests showed a larger variance for Beginner dancers in Time 1, but not Time 2 (see Fig. 1a, b, and c. Time and Experience effect for each variable).

Hypothesis 4. After controlling for the initial Depression level, initial Self-esteem and Self-judgment will predict the change in Depression levels after two years, and Self-esteem will moderate the Self-judgment effect on the change in Depression levels. Multiple regression was performed to investigate the predictors of change in depression levels after two years (DeltaDep = Depression Time 2 subtracted from Depression Time 1). The model included Time 1 Depression, Self-esteem, and Self-judgment in both Time 1 and Time 2, and the interaction between Self-esteem and Self-judgment at each time point (centralized). Twenty-three participants were included in this analysis. Our hypothesis was confirmed with a significant regression model, F(7, 22) = 4.473, p = .007, R² = 0.676. Initial depression and Self-judgment predicted DeltaDep, β = −0.476, p = .03, and β = 0.633, p = .01, respectively. Importantly, the interaction between Self-esteem and Self-Judgment in Time 2 significantly predicted DeltaDep, β = −0.603. Self-esteem in Time 2 moderated the effect of Self-judgment in Time 2 on DeltaDep. That is, when Self-esteem is at the highest level, Self-judgment was not associated with DeltaDep (R² = 0.07). In contrast, when Self-esteem is lower, there is a positive correlation between Self-judgment and DeltaDep (R² = 0.424): Higher Self-judgment was associated with minimal change in Depression, while lower Self-judgment was associated with higher change in Depression. See Table 4 for the main results.

Multiple regression with change in Depression levels after two years (DeltaDep) as a dependent variable, Depression in Time 1, Self-esteem, Self-judgment, and the interaction of Self-esteem with Self-judgment in Times 1 and 2. p < .01 = **, p < .05 = *.

Our study examined the short and long-term effects of GILA among older women on three interactive psychological factors: self-esteem, depression, and self-judgment. We found that Experienced dancers had higher self-esteem and lower self-judgment levels than Beginners, but depression levels did not differ. Examining long-term effects, participants who danced for two years or more showed that depression levels decreased significantly. Considering dancers' experience, we revealed that, over time, depression levels were only reduced among the Experienced dancers; self-esteem did not differ, but there was a larger decrease in self-judgment for Beginner dancers after two years. Lastly, we found that regardless of initial depression level, initial self-judgment predicted the change in depression level after two years, and Time 2 self-esteem moderated the effect of Time 2 self-judgment on the change in depression levels after two years. That is, after two years, when Self-esteem was high, there was no association between Self-judgment and change in depression, but when self-esteem was low, higher self-judgment was associated with a smaller change in depressive symptoms.

Examining the psychological constructs of self-esteem and self-judgment, we found that self-esteem was higher and self-judgment was lower among experienced dancers compared to beginners. In her methodology, the GILA group leader, Galit Liss, states that she does not focus on difficulties or barriers that the dancers raise, but instead encourages them to work with what they have, with the body they have now, believing that they will work it out through their bodies. Dancing in front of the group, their families, and sometimes even unrelated audiences promotes acceptance and releases thoughts and fears about the body's ability and meaning.

The change over time allows a more complete understanding of the suggested process by Liss. We found that over two years of dancing, experienced dancers did not report a change in their self-judgment, whereas beginner dancers did. While the baseline levels of self-judgment were significantly lower and better for experienced than beginner dancers, by the end of two years, the improvement (decrease) in beginners' self-judgment levels reached the same point as experienced dancers. The endpoint means and variability were similar for both groups, suggesting a possible explanation for the lack of decrease among experienced dancers: As beginners, experienced dancers also improved their self-judgment. At a certain point, the measure seems to reach its bottom limit. This can indicate a floor effect of the measurement or an optimum point of self-judgment suitable for the person's well-being. Either way, our results show that after two years of dancing, self-judgment is low and beneficial for the dancing woman. An additional factor that may contribute to the reduction in self-judgment is the use of accompanying music, particularly its rhythm and organizing tempo. Similar to cognitive-behavioral techniques, where regulating breathing patterns can reduce anxiety by shifting attention away from ruminative thinking, focusing on the music may provide a parallel attentional anchor (Diaz, 2013; Quiroga Murcia et al., 2010). Engagement with the musical structure during dance, especially while creating solo movements, may facilitate attentional absorption and diminish internal critical dialogue. This redirection of attention away from evaluative self-monitoring and toward sensory-motor synchronization may also contribute to the observed decrease in self-judgment among beginner dancers.

Although, as a main effect, we did not see a difference in depressive symptoms between experienced and beginner dancers, when considering the effects of time, the difference is evident: The interaction revealed that for beginner dancers, there was no significant change in depression levels over time, while it was decreased for experienced dancers. We believe that this pattern should be viewed in the context of our longitudinal study and as part of historical events. During the COVID-19 crisis, the older adult population was considered to be at the highest risk. Many governments had recommended maintaining social distancing, which had led to greater feelings of loneliness and social isolation, which in themselves are risk factors for depression (Luchetti et al., 2020; Noone et al., 2020; Zamir, 2020). Studies showed an increase in depression levels among all populations, including older adults (Armitage & Nellums, 2020). GILA dancers continued their dance sessions online during lockdowns, and our results show no indication of any increase in depression among them. Though we did not administer a control group during that period, comparing national and worldwide data clearly makes GILA dancers stand out. This effect aligns with the findings that online dance activity was a resilience factor against depression and stress (Bohn & Hogue, 2020). Interestingly, experienced dancers even showed a decrease in their depressive symptoms over time. We speculate that these dancers were aware of their unique situation and embraced the opportunities to continue the beloved activity of group dancing.

Self-esteem played a moderating role in the relationship between self-judgment and the decrease in depression. The impact of self-judgment on reducing depression levels was evident only in participants with lower self-esteem. For dancers with lower self-esteem, high self-judgment resulted in a smaller decrease in depression symptoms. This finding is consistent, as self-judgment reflects a rigid way of thinking associated with low psychological flexibility, which makes it more challenging to cope with stressful events and age-related changes (Shmotkin, 2005). Shmotkin (2005) described subjective mental well-being as a dynamic adaptive system and explored the mental challenges associated with aging. Mental well-being supports the psychological ability to 'seek happiness' despite 'hostile world scenarios' threatening mental and physical integrity. According to Shmotkin, hostile world scenarios (HWS) are self-beliefs about actual or potential threats to human integrity. Maintaining mental well-being and meaning in a life constantly challenged by these threats, such as natural disasters, accidents, terminal illnesses, financial deprivation, suffering, and death (Shmotkin et al., 2016), is crucial. When the hostile world scenario system is strongly activated, and mental well-being and meaning do not provide sufficient balance, individuals may constantly feel they are surviving in a threatening world. Conversely, when there is a sense of attachment, meaning, and belonging, people are, on the one hand, vigilant towards possible threats, and on the other hand, have psychological flexibility and a sense of capability. In the case of GILA dancers, those with high self-judgment appear to lack sufficient psychological flexibility and have an imbalanced set of beliefs characterized by strong, hostile world scenarios and an insufficient sense of meaning to promote happiness. Hence, the decrease in depressive symptoms is less pronounced. This effect of self-judgment was not apparent for dancers with high self-esteem. In terms of HWS, it seems that self-esteem plays a sufficient role in resilience and coping, and when it is lower, self-judgment provides an alternative buffer for improving well-being. This understanding highlights the value of GILA, as they have been shown to decrease self-judgment over time from the onset of participation.

The current study is an uncontrolled ecological longitudinal study, which inherently comes with limitations that we will expand on in three main points: First, there is no randomization and no control group for comparison. Second, due to the longitudinal nature of the study, it is subject to maturation, history-related alternative explanations, and attrition. Lastly, we relied solely on voluntarily self-reported measurements, which can lead to response bias. However, we believe that these features are integral to the GILA's flexible, fluid design. Once a novice dancer has completed their first year and has performed a solo dance, they are eligible to join the experienced group. As a longitudinal dancing group, it must overcome difficulties such as those encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic. As older adults are a vulnerable group, continuing to dance together was more challenging; however, GILA groups successfully transitioned from physical dancing to an online setting. By analyzing two years' data, regardless of the calendar year, we have likely mitigated the historical effect of a specific year and increased variability. Consequently, finding robust effects under this large variability with a small sample size can reinforce our significant findings. Nonetheless, we cannot address a selection effect in this study, as participants were not randomly assigned. It is possible that those who chose to participate in the group dancing and were included in the long-term analyses already had characteristics relevant to the observed improvement over time. However, even in between-subject measurements, those that included a large group of individuals who participated only once, the results trend in the same direction, serving as a quasi-control group. Since we cannot definitively rule out alternative explanations related to history, maturation, or selection, it is crucial to continue examining and replicating these variables over time in different regions with diverse populations and larger samples. This way, the variability may enable generalization despite the ecological limitations. Applying physical measurements that do not rely on self-reports could further deepen our understanding of the observed effects.

In conclusion, participating in GILA—both in the short and long term, which includes performing a solo dance at the end of the first year—can benefit older women by improving their well-being. These benefits include lower self-judgment, higher self-esteem, and reduced depression. The study highlights the complex interplay between depression, self-judgment, and self-esteem, noting the protective role of self-esteem in mitigating the adverse effects of self-judgment on depression. GILA is multifaceted, combining physical activity, social interaction, and creative expression to create a supportive environment. This environment encourages older women to embrace their abilities, challenge self-limiting beliefs, and experience personal growth over time. Solo and group performances appear to be vital in reducing negative self-judgment and promoting acceptance. The study also underscores the importance of future research to address current limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the program's long-term effects, thus contributing to resilience.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used Grammarly, OpenAI - Chat GPT, Google - NotebookLM, and Microsoft - Copilot to improve the manuscript's readability (primarily for proofreading, rephrasing, and summarizing). After using each tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed. OpenAI - Chat GPT was used to generate the initial version of Fig. 1 presented in this article. The resulting code was subsequently reviewed and refined by an expert programmer to ensure accuracy and to make visual adjustments appropriate for publication. The authors confirmed that the values presented in the final figure exactly match the original dataset. We take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data statementAvailable upon request to maintain personal confidential and sensitive information secure.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the MA students whose critical support and leadership were invaluable throughout the research process. Their commitment to the theoretical framework, meticulous planning, data collection, logistical coordination, and other essential contributions has played a central role in advancing this ongoing work. We especially want to thank Yael Barak, Yarden Goldin, Youli Hert, Shir Reich, and Zach Segall.

Special thanks to the Blavatnik Postdoctoral Fellowship Programme and the ISEF-Price foundations for supporting ZZC during the publication process.