Edited by: Em. Professor Gualberto Buela-Casal

(University of Granada, Granada, Spain)

Dr. Katie Almondes

(Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, NATAL, Brazil)

Dr. Alejandro Guillén Riquelme

(Valencian International University, Valencia, Spain)

Last update: December 2025

More infoDepression, anxiety, and insomnia have been identified as risk factors for suicidality. However, limited research has explored the interplay among these mental health problems at a symptom level and how they relate to suicidality, especially in adolescents - a group undergoing substantial developmental changes, such as intrinsic circadian delay. This study aimed to examine the symptom networks of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in relation to suicidality and chronotype, and to identify potential bridge symptoms linking these symptom clusters.

MethodsA total of 3037 adolescents (Mean age = 14.56 ± 1.77; 35.40 % male) were recruited. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). Network estimation methods were employed to identify central and bridge symptoms and to compare the network models across gender and chronotype groups.

ResultsThe prevalence of probable depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10), anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10), and insomnia (ISI ≥ 9) was 32.6 %, 23.1 %, and 30.5 %, respectively. About 27.7 % of adolescents reported suicidality within the past two weeks. Within the network, difficulty maintaining sleep emerged as the most influential node, followed by uncontrollable worry, distress caused by sleep disturbances, trouble relaxing, and sad mood. Additionally, sad mood, sleep disturbances, fatigue, and guilt from the depression cluster, and uncontrollable worry from the anxiety cluster were identified as the strongest bridge symptoms in the network. The symptom networks did not differ in global edge strength and network structure across genders and chronotypes (ps > 0.10). Notably, all identified bridge symptoms, except fatigue, were directly linked to suicidality.

ConclusionOur findings highlighted the potential transdiagnostic significance of sad mood, sleep disturbances, fatigue, guilt, and uncontrollable worry in the development and maintenance of the comorbidity of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and suicidality in adolescents. Targeting these symptoms may inform more effective intervention strategies to manage psychopathology and reduce suicidality in this population.

Adolescence is a critical developmental period characterised by substantial biological, psychological, social, and behavioural changes. For example, intrinsic circadian delay is a hallmark of this transitional phase, associated with an increased prevalence of evening chronotype, i.e., a circadian preference for later bedtimes and wake times (Randler et al., 2017). Adolescents also face heightened challenges in social and academic aspects. These changes may increase their vulnerability to sleep and mental health problems (Cheung et al., 2023; Crowley et al., 2007). In fact, the majority of mental disorders emerge by the age of 18, and early onset of psychiatric conditions is linked to more enduring mental health problems, as well as a higher risk of developing psychiatric comorbidities and suicidality in later adulthood (Caspi et al., 2020; Mulraney et al., 2021; Solmi et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2012). Notably, suicide is increasingly recognised as a critical public health issue among adolescents globally, with approximately 14 % of adolescents aged 12–17 years having considered attempting suicide in the past year (Biswas et al., 2020). Given the developmental complexity of adolescence, there is a need to focus on the common mental health issues in young people to identify the key factors contributing to the comorbidity and to inform the development of early prevention and intervention programmes (Kieling et al., 2011).

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental disorders among adolescents and represent the two leading causes of mental health burden globally (Collaborators, 2021; World Health Organization, 2017). Meta-analyses have found a high prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents both before (depression: ∼14.1 %, anxiety: ∼19.1 %) (Barker et al., 2019) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (depression: ∼28.6 %, anxiety: ∼25.5 %) (Chen et al., 2022; Racine et al., 2021). Depression and anxiety are highly comorbid (Gorman, 1996) and are both associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes, including increased substance and alcohol use (Hunt et al., 2020; McCauley Ohannessian, 2014), academic difficulties (Brumariu et al., 2023; Dupere et al., 2018), and poor physical health (Cobham et al., 2020; Stubbs et al., 2017). Meanwhile, sleep problems, particularly insomnia, presented as difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, as well as early morning awakening, are common in individuals with depression or anxiety, with prevalence rates ranging from 21.5 % to 68.6 % (Chan et al., 2020; Li et al., 2018). About 48 % of children and adolescents diagnosed with depression meet the diagnostic criteria for insomnia disorder (Hysing et al., 2022). Similarly, the prevalence of comorbid insomnia in adolescents with any anxiety disorder can be as high as 42.9 % (Brown et al., 2018). Longitudinal studies have suggested potential reciprocal relationships between depression, anxiety, and insomnia (Staner, 2010; Yang et al., 2023). For instance, a recent longitudinal study conducted in 6995 adolescents (mean age = 14.86 years, 51.4 % male), adopting a three-wave cross-lagged panel model, showed that stress, insomnia, and depression/anxiety symptoms each predicted their own increase as well as bidirectionally predicted each other over time (Yang et al., 2023). Furthermore, previous research has identified shared predisposing or precipitating factors, such as genetics, neural and neurobiological abnormalities, and psychological dysfunction (e.g., emotional dysregulation, negative emotionality) among these three conditions (Blake et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2023; Goodkind et al., 2015; Lane et al., 2019; McTeague et al., 2017). For example, a Mendelian randomised phenome-wide association study found that genetic risk score for insomnia symptom was not only associated with an increased risk of insomnia but also other mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety (Gibson et al., 2023). Altogether, the evidence suggests that depression, anxiety, and insomnia may share similar underlying mechanisms.

Suicidality is often linked to depression, anxiety, and insomnia in adolescents (Chan et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2024; Hua et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2021). For instance, adolescents experiencing insomnia symptoms were 2.1 times more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those without insomnia symptoms (Chan et al., 2020). Given the high comorbidity among depression, anxiety, and insomnia, as well as their links to suicidality, there is a growing recognition of the importance of addressing common underlying mechanisms across these disorders. This transdiagnostic approach, which focuses on shared features rather than disorder-specific factors, has been proposed as a more promising strategy (Harvey, 2008). However, no studies to date have investigated the relationships between individual symptoms of mental health problems and suicidality, specifically, how individual symptom interacts with others and contributes to suicidality. Such investigations are essential for developing transdiagnostic interventions that can prevent the occurrence of these problems, reduce symptom progression, and provide effective suicide prevention measures (Kieling et al., 2011).

Network analysis has been increasingly recognised over the past decades as a valuable approach for understanding psychopathology (Contreras et al., 2019). This method can identify key symptoms that play the most important role in influencing other symptoms within a network model, offering insights into which symptoms are essential for maintaining the disorders and informing targeted treatment strategies. In network analysis, symptoms are presented as nodes, and the connections between symptoms are referred to as edges. Some recent studies have identified potential bridge symptoms connecting depression, anxiety, and insomnia across somatic (e.g., sleep disturbance, fatigue), affective (e.g., guilt, feeling afraid, irritability), and behavioural (e.g., motor activity, trouble relaxing, restlessness) domains (Bai et al., 2022; Bard et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2022). Nonetheless, it remains unclear how these symptoms are related to suicidality. Moreover, whilst previous studies have highlighted circadian issues (e.g., chronotype) in relation to poor mental health and sleep in adolescents (Cheung et al., 2023), circadian factors have not been considered in the previous research with network analysis. Therefore, there is a need for specific investigation targeting common mental health problems in adolescents to gain a comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms from a network perspective.

The current study aimed to examine the associations between the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in adolescents using a networking approach. Specifically, this study sought to 1) examine and identify the most central symptoms and bridge symptoms in the network, 2) understand the relationship between suicidality and the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia, and 3) explore the network connectivity across chronotype preference with a focus on eveningness.

MethodParticipants and proceduresFrom October 2022 to December 2023, using a purposive sampling approach, adolescents aged 12 to 20 years were recruited from secondary schools to complete a battery of self-report measures on sleep, depression, and anxiety. Inclusion criteria included: (1) being a secondary school student aged between 12 and 20 years, and (2) being able to read traditional Chinese. The specific age range of 12–20 years was chosen to capture a broader developmental period and to align with prior research (Chen et al., 2021; Clarke et al., 2015). Exclusion criteria included: (1) having a history of clinically diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder) or severe mental illness (e.g., psychotic disorder, bipolar disorders) based on the self-report psychiatric history.

Ethical considerationsAll the study participants provided their written informed consent and parental consent for those aged under 18. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Institution.

Measures2.3.1 Insomnia Symptoms. Insomnia symptoms were assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), consisting of 7 items measuring symptoms of DSM-5 Insomnia disorder in the past two weeks (Bastien et al., 2001). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater levels of insomnia (0–28). Probable insomnia in this study was defined as a total score on ISI ≥ 9 (suggested cut-off for clinical insomnia in adolescents) (Chung et al., 2011). The ISI has demonstrated good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents. The internal consistency in the current sample was Cronbach’s α = 0.86.

2.3.2 Depressive Symptoms and suicidality. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which measures symptoms of major depressive disorders according to DSM-5 in the past two weeks. Each item ranges from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (Kroenke et al., 2001), with higher scores indicating greater levels of depression (0–27). Probable depression in this study was defined as a total score on PHQ-9 ≥ 10 (suggested cut-off for clinical depression in adolescents) (Levis et al., 2019). In particular, the presence of suicidality was identified based on the suicidal ideation item of the PHQ-9: “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself.” A rating of 0 was considered as the absence of suicidality and other ratings (i.e., 1, 2, 3) were considered as the presence of suicidality. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents (Leung et al., 2020). The internal consistency in the current sample was Cronbach’s α = 0.86.

2.3.3 Anxiety Symptoms. Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the General Anxiety Disorder – 7 items (GAD-7), which measures the symptoms of general anxiety disorder according to DSM-5 in the past two weeks (Spitzer et al., 2006). Each item ranges from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with higher scores indicating greater levels of anxiety (0–21). Probable anxiety in this study was defined as a total score on GAD-7 ≥ 10 (suggested cut-off clinical anxiety for adolescents) (Spitzer et al., 2006). The GAD-7 has been validated in Chinese adolescents (Sun et al., 2021). The internal consistency in the current sample was Cronbach’s α = 0.93.

2.3.4 Chronotype. Chronotype (MSFsc) was assessed based on the midpoint of sleep obtained from The Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) (Roenneberg, 2012). It was estimated based on the midpoint between sleep onset and wake-time on work-free days (midpoint of sleep on work-free days: MSF), adjusted for longer sleep due to insufficient sleep on workdays. A greater score in MSFsc indicates a tendency for eveningness. Median split was performed to cluster adolescents into low eveningness and high eveningness for subsequent analyses.

2.3.5 Demographic Information. Information on demographic characteristics, such as age and gender, was also collected.

General analysis routineDescriptive statistics were used to summarise the demographic characteristics of the sample and study items (Table 1). To address the debate on the optimal way to model trichotomous items in network analysis, the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI items were dichotomised to “0” and “1” to indicate the absence (item originally rated as 0) and presence (item originally rated as 1, 2, or 3) of symptoms (Fried et al., 2015). The chi-square tests were conducted for the categorical variables of the presence of symptoms across genders and chronotypes.

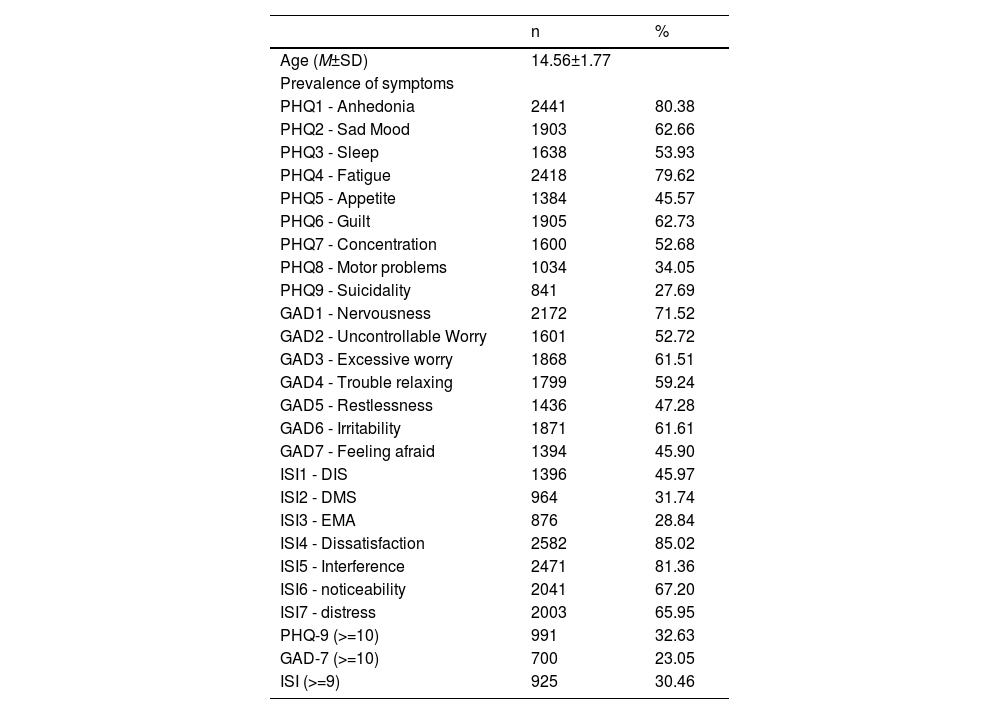

Descriptive statistics of demographic information and measurement items.

Note. DIS = Difficulty Initiating Sleep; DMS = Difficulty Maintaining Sleep; EMA = Early Morning Awakening; GAD = General Anxiety Disorder; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; M = Mean; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; SD = Standard Deviation.

2.4.1 Estimation Method. Network models that combined all items from PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI (23 nodes in total) were estimated using an Ising model that depicts associations between binary variables using pairwise log-linear relationships (van Borkulo et al., 2014). The eLasso based on the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (Epskamp et al., 2012) was utilised to limit spurious or false positives, allow the estimates to shrink to zero, and enhance the interpretability of networks with a sparse network from binary data.

2.4.2 Accuracy and Stability of Edge-Estimates. The accuracy and stability of edge weight estimates were evaluated using the bootnet package (Epskamp et al., 2018; Epskamp & Fried, 2015) to ensure the robustness of the results. A non-parametric bootstrapping method based on 1000 bootstrap samples was utilised.

2.4.3 Statistical Packages. Analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2. The network estimation was conducted with estimateNetwork function in bootnet package (Epskamp et al., 2018; Epskamp & Fried, 2015) and Ising Fit package (van Borkulo et al., 2014). The qgraph package was used to visualise the network (Epskamp et al., 2012). The Spring layout or Frucherman-Reinglod algorithm was adopted to illustrate the combined network, and the Circle layout was utilised to plot the comparison networks (Fruchterman & Reingold, 1991). Furthermore, flow networks were plotted using the qgraph package to illustrate how suicidality connects to other symptoms. The goldbrick function from the networktools package was used to check the potential redundancy of the nodes in the network model (Jones, 2018).

Analysis-Specific routine2.5.1. Centrality Indices. Expected influence (EI) was used to assess the centrality of each node and identify the most influential node in the network (Robinaugh et al., 2016), where nodes with the highest EI values were considered the most influential in the symptom network. Bridge expected influence (BEI) was used to identify the nodes (i.e., bridge node) that connect depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptom communities. Bridge nodes were selected using an 80th percentile cut-off on BEI value (Jones et al., 2021). The bootnet package (Epskamp et al., 2018; Epskamp & Fried, 2015) with a case-dropping bootstrap method based on 1000 bootstrap samples was used to estimate the accuracy of centrality indices of the network structure. A correlation stability coefficient (CS-coefficient) was obtained for edge weights, EI, and BEI for each network from the bootstrapping procedure. The CS-coefficient indicates the proportion of cases that could be dropped from the analyses while preserving a correlation at least r = 0.70, which is the default value in the bootstrapping procedure, with the original centrality coefficients within a 95 % confidence interval (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). A CS coefficient of 0.5 is recommended for the assessment of the stability of the network models (Epskamp & Fried, 2018).

Node predictability was estimated using the mgm package (Haslbeck & Waldorp, 2015) to understand how well each node can be predicted by its neighbouring nodes that shared an edge with and reflected by the normalised accuracy measure, as the symptom variables are binary (Haslbeck & Fried, 2017). The predictability of each node was visualised as a ring-shaped pie chart surrounding the node in the network models.

2.5.2 Network Comparison. The Network Comparison Test was utilised to evaluate global and local connectivity across two groups with the R package NetworkComparisonTest (van Borkulo et al., 2023) with 1000 iterations. Post-testing on specific edges was conducted when the omnibus network invariance test was significant.

ResultsA total of 3037 eligible adolescents (Mean age = 14.56 ± 1.77; range 12–20; 35.40 % male) were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the demographic, chronotype, ISI, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 items are shown in Table 1. Prevalence rates of probable depression, anxiety, insomnia symptoms, and suicidality were 32.63 %, 23.05 %, 30.46 %, and 27.69 %, respectively. Tables S1-S2 show the results for different genders and chronotype groups.

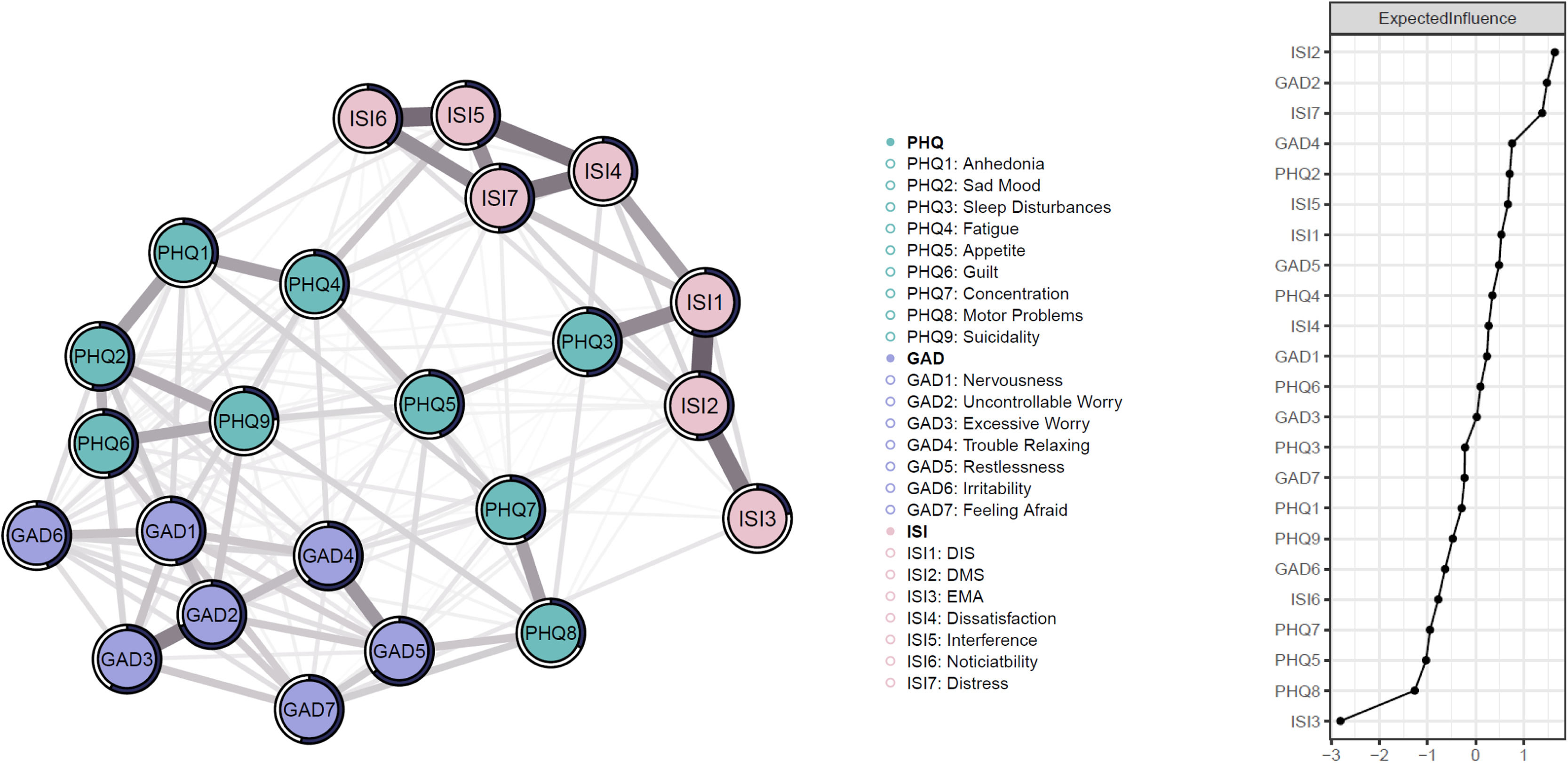

Network structureFig. 1 illustrates the network model of depression, anxiety, and insomnia and the expected influence (EI) value for each node. In the combined network, 149 of the 253 possible edges (58.89 %) were non-zero with mean weight = 0.25), which indicated great interconnectedness among symptoms. Edge weights ranged from 0.03 (PHQ3–GAD3) to 1.89 (ISI1–ISI2). Difficulty maintaining sleep (ISI2) was the most influential node in the network model, followed by uncontrollable worry (GAD2), distress (ISI7), trouble relaxing (GAD4) and sad mood (PHQ2). In contrast, early morning awakening (ISI3) was the least influential node. The network demonstrated good stability as supported by a CS-coefficient for EI value (CS=0.75).

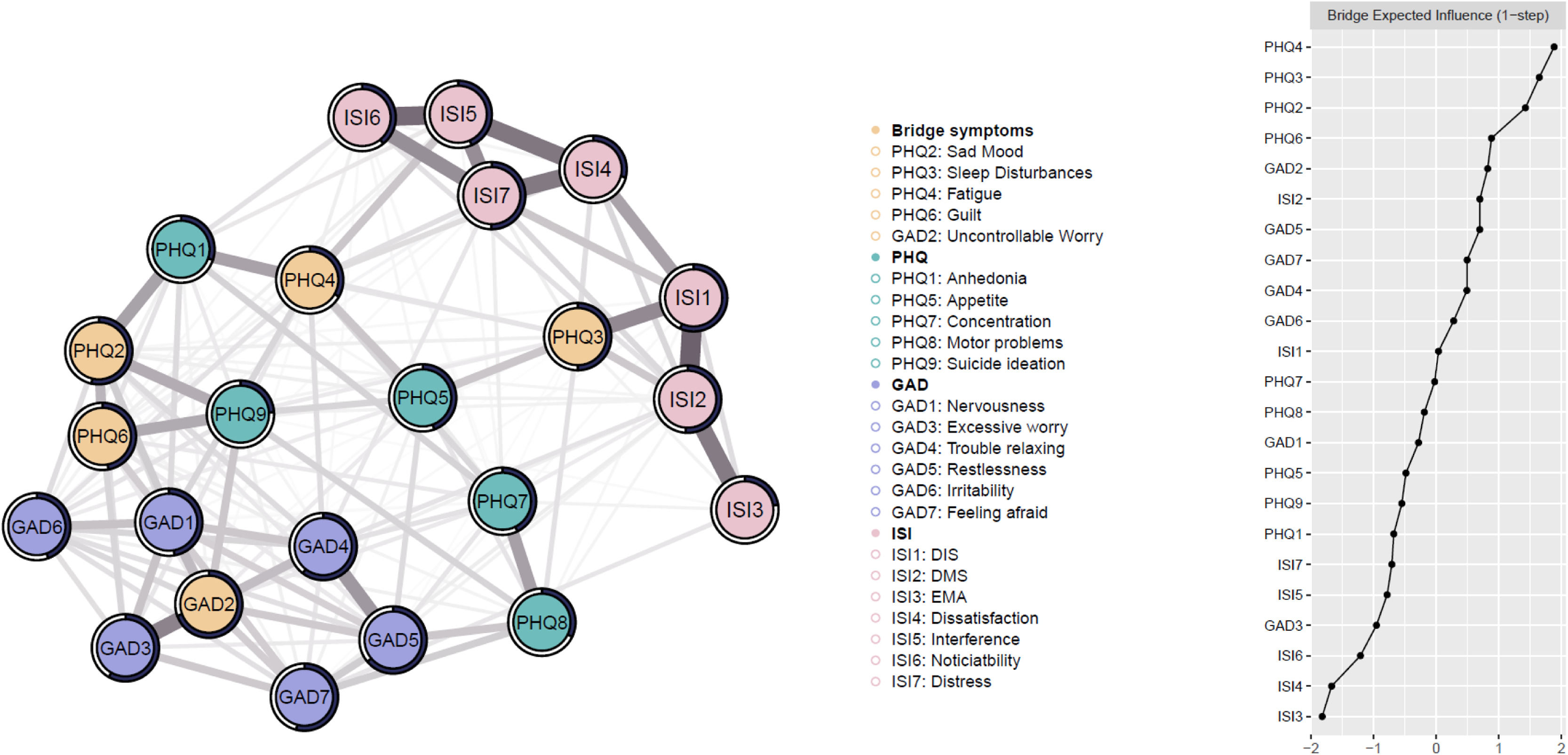

Fig. 2 illustrates the network with bridge symptoms and the bridge expected influence (BEI) value for each node. The network with bridge symptoms demonstrated good stability, as supported by a high CS-coefficient for BEI values (CS = 0.75). The model showed that fatigue (PHQ4), sleep disturbances (PHQ3), sad mood (PHQ2), guilt (PHQ6), and uncontrollable worry (GAD2) emerged as bridge nodes in the network model. The network demonstrated good stability as supported by a CS-coefficient for BEI value (CS = 0.67). Results of the non-parametric and case-dropping bootstrapping analysis were reported in supplementary materials (Fig. S1 – S5).

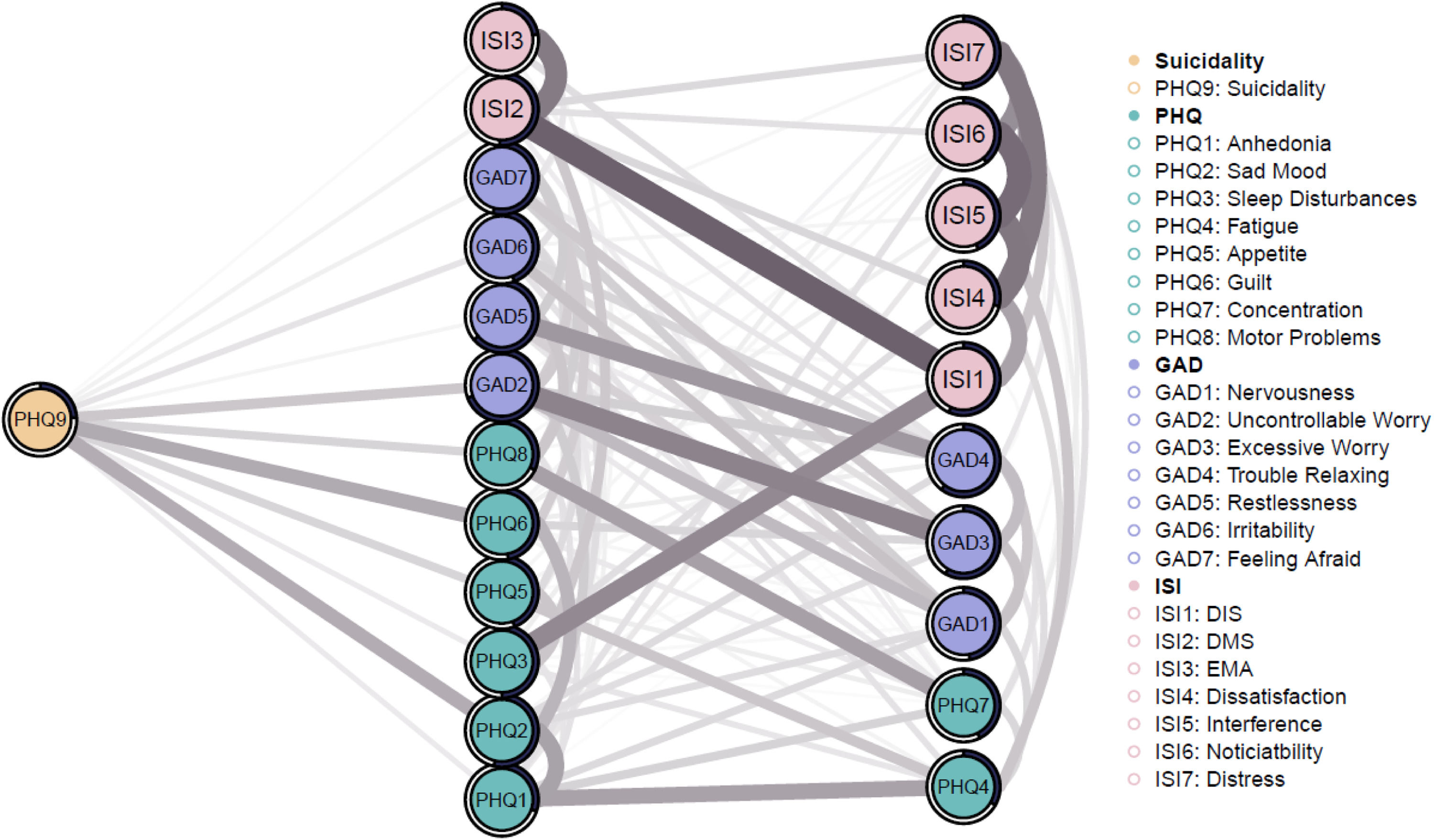

Fig. 3 shows the flow network illustrating connections between suicide ideation and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia. The 12 symptoms in the middle of the network were directly connected to suicidality, and the remaining symptoms on the right were indirectly connected to suicidality. Symptoms most strongly connected to suicidality were guilt (PHQ6; Edge weight = 0.99), followed by sad mood (PHQ2, Edge weight = 0.96), uncontrollable worry (GAD2, Edge weight = 0.65), motor problems (PHQ8; Edge weight = 0.50), and appetite (PHQ5; Edge weight = 0.49).

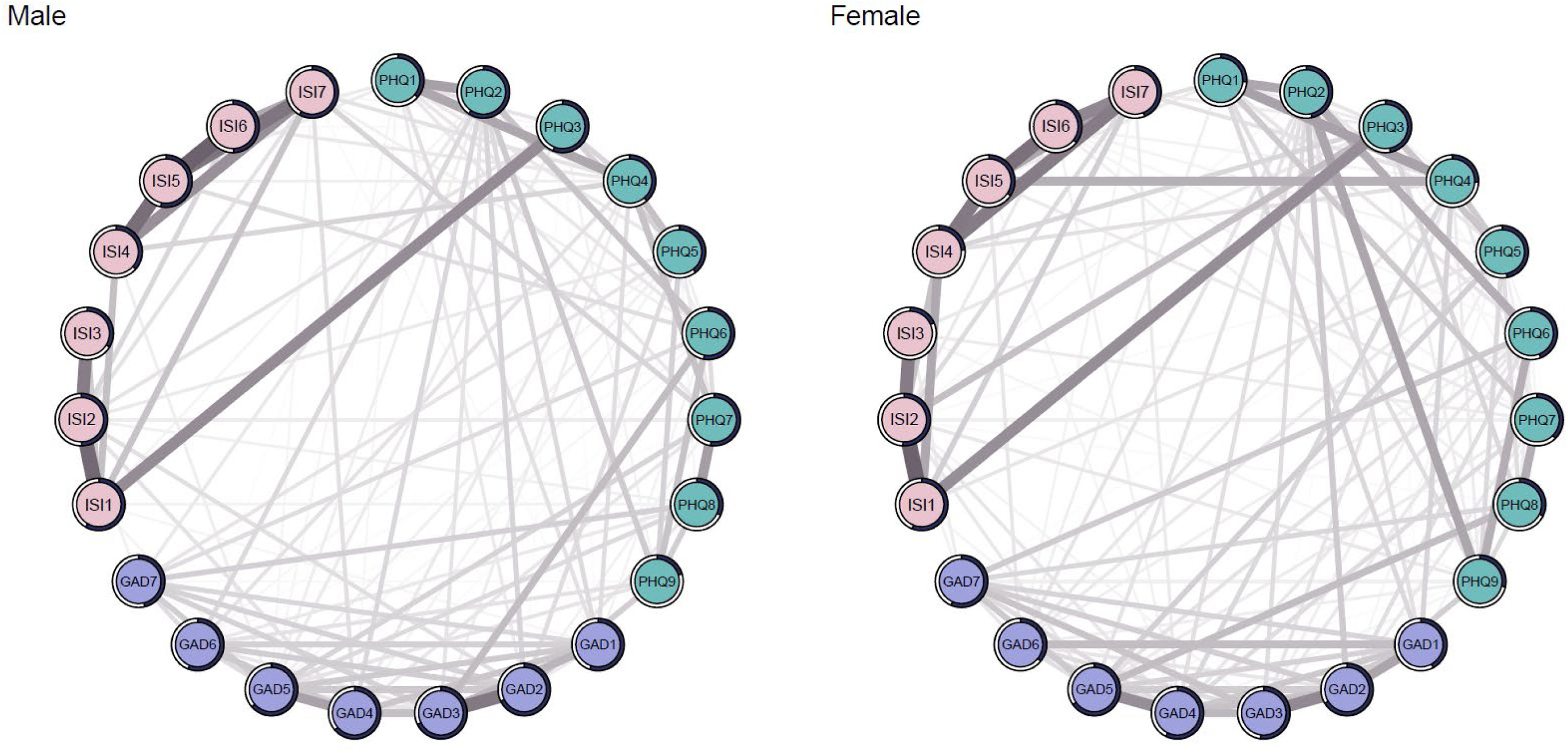

Group comparison3.3.1 Gender Comparison. The networks of depression, anxiety, and insomnia for boys and girls are shown in Fig. 4. The centrality indices were reported in the Supplementary (Fig. S6). The two networks did not differ significantly in global edge strength (boys: 58.97 versus girls: 57.66; S = 1.32, p = 0.55) or network structure (M: 0.54, p = 0.96) (Fig. S7). Flow networks of suicidality across genders are shown in Fig. S8.

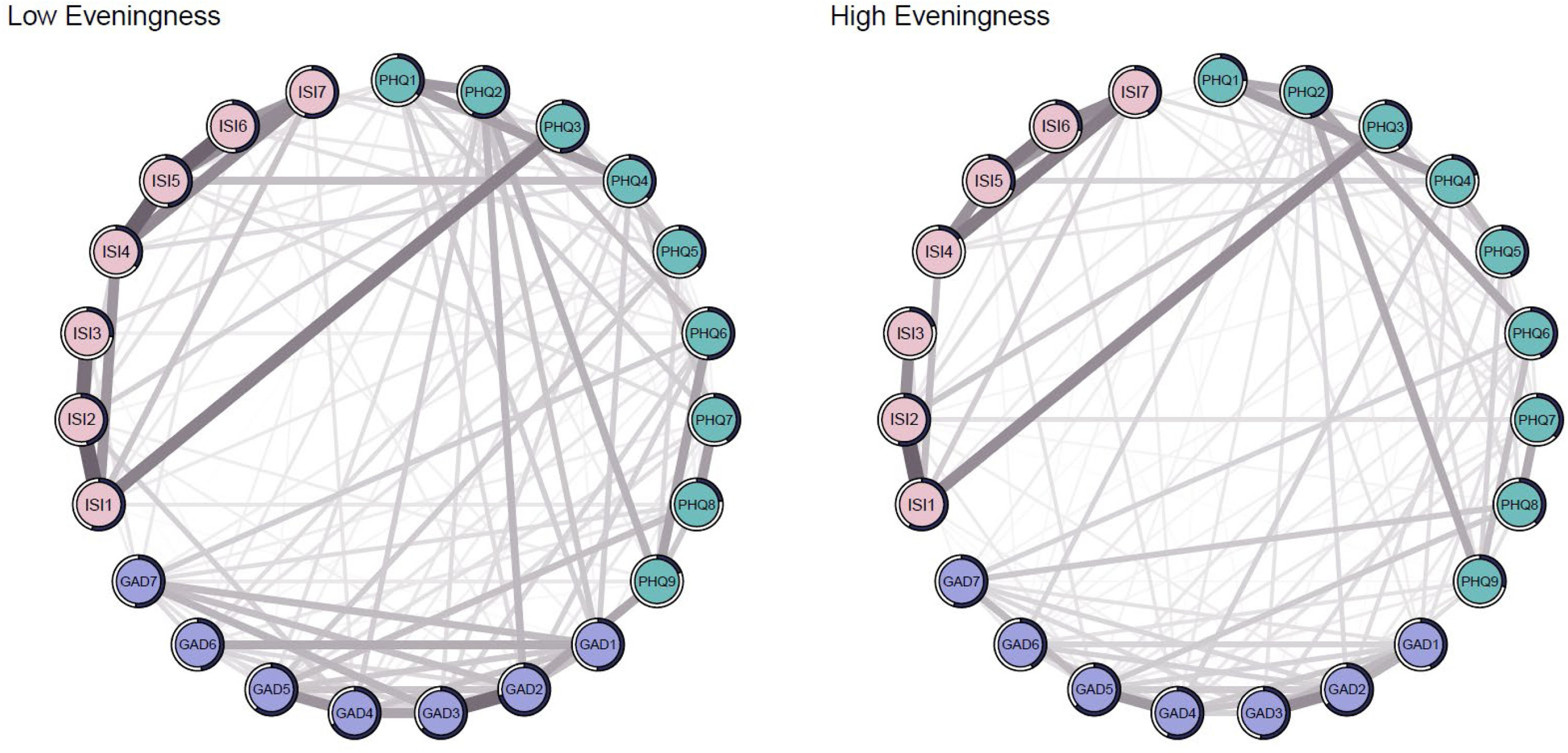

3.3.1 Chronotype Comparison. The networks of depression, anxiety, and insomnia for high eveningness and low eveningness are shown in the appendices (Fig. 5). The centrality indices were reported in the Supplementary (Fig. S9). The two networks did not differ significantly in global edge strength (high eveningness: 57.94 versus low eveningness: 59.53; S = 1.59, p = 0.87) or network structure (M: 0.79, p = 0.28) (Fig. S10). Flow networks of suicidality across chronotypes are shown in Fig. S11.

DiscussionThe findings of the current study highlighted and extended the understanding of how depression, anxiety, and insomnia are inter-connected and maintained at the symptom-level in adolescents, as well as how their individual symptoms are associated with suicidality from a network perspective. We found that the most influential individual symptom was difficulty maintaining sleep (ISI2), followed by uncontrollable worry (GAD2), distress (ISI7), trouble relaxing (GAD4), and sad mood (PHQ2). Moreover, the specific symptoms connecting depression, anxiety, and insomnia were fatigue (PHQ4), sleep disturbances (PHQ3), sad mood (PHQ2), guilt (PHQ6), and uncontrollable worry (GAD2), most of which were directly linked to suicidality (PHQ9). Despite previous research suggesting gender differences and a negative association between eveningness preference and mental health outcomes (Cheung et al., 2023; Ohannessian et al., 2017; Salk et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016), our Network Comparison Test results showed comparable network structure and connectivity, implying that the activation patterns of psychopathology might be similar regardless of gender and chronotype (high vs. low eveningness).

The central symptoms identified within the overall symptom network encompassed somatic (difficulty maintaining sleep [ISI2]), cognitive (uncontrollable worry [GAD2]), affective (distress due to sleep disturbances [ISI7], and sad mood [PHQ2]), and behavioural (trouble relaxing [GAD4]) domains. The findings suggest that these symptoms play a crucial role in the activation and maintenance of the overall symptom network of adolescent depression, anxiety, and insomnia. This observation corroborated the literature that examined the symptom network of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in the adult population (Bai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2022). Additionally, a previous experimental study has shown that sleep continuity disruption could exert a greater deteriorating effect on positive mood over time compared to restricted sleep opportunities through delayed bedtime (Finan et al., 2015). This underscored the clinical relevance of sleep maintenance problems, particularly in relation to anhedonia, a core symptom of depression. Given that central symptoms tend to have greater connectivity with other symptoms, clinicians and researchers could consider focusing on these identified symptoms when developing screening tools aimed at recognising common mental health issues. Addressing these core symptoms may help to prevent the activation of comorbid depression, anxiety, and insomnia in adolescents. It is worth noting that sleep problems often emerged as one of the most influential symptoms in the depression-anxiety-insomnia network across adult samples, regardless of the measurement tools employed (Bai et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022). Thus, interventions targeting sleep disturbances, particularly sleep continuity, may be essential for improving global sleep and mental health. In this regard, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to be effective in addressing not only sleep disturbance but also depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults, albeit limited data in adolescents (Benz et al., 2020; Trauer et al., 2015; van der Zweerde et al., 2019). It should be noted that CBT-I has demonstrated efficacy in improving difficulty maintaining sleep, as evident by reduced wake after sleep onset (WASO) following treatment (Trauer et al., 2015; van der Zweerde et al., 2019). There has also been some evidence showing cognitive-behvaioural prevention programmes targeting insomnia as a promising means to prevent the occurrence of insomnia and improve mental health in at-risk adolescents (Chan et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023).

Additionally, our findings demonstrated the comorbid relationship of depression, anxiety, and insomnia at the symptom level via identified bridge symptoms. Five symptoms were recognised as bridge symptoms, including somatic symptoms - fatigue (PHQ4) and sleep disturbances (PHQ3), affective symptoms - sad mood (PHQ2) and guilt (PHQ6), and cognitive symptoms - uncontrollable worry (GAD2). These bridge symptoms may have transdiagnostic significance by connecting and activating symptoms across the different psychiatric conditions within the comorbid network of depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Consistent with Li et al. (2024), fatigue (PHQ4) emerged as the most prominent bridge symptom in the current network, showing the strongest connection with interference with functioning (ISI5). Our findings may highlight the necessity of addressing fatigue and enhancing vigour or vitality to tackle the comorbidities of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among adolescents. Fatigue is often associated with poor sleep and lower activity levels among adolescents (Herring et al., 2018). A recent meta-analysis further indicated that physical activity is negatively associated with poor sleep and mental health outcomes (Li et al., 2023). Promoting physical activity has been suggested to benefit both sleep and mental health outcomes (Li et al., 2023; van Sluijs et al., 2021). Meanwhile, CBT-I has also been suggested as a promising intervention for improving fatigue among individuals with insomnia disorder (Benz et al., 2020). Sleep disturbances (PHQ3), sad mood (PHQ2), and guilt (PHQ6) also appeared in prior studies as the key components of the comorbid network linking depression, anxiety, and insomnia (Bai et al., 2022; Cai et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022). For interconnectivity, our findings showed that sleep disturbances (PHQ3) were most strongly associated with difficulty initiating sleep (ISI1), implying that trouble falling asleep is the most overlapping sleep problem in this context of comorbidity. Furthermore, sad mood (PHQ2) was most strongly connected to uncontrollable worry (GAD2), which in turn had the most substantial link to suicidality (PHQ9). However, previous studies did not identify uncontrollable worry (GAD2) as a bridge symptom, suggesting that being unable to stop or control worrying might be unique in the adolescent sample. The triad of depressed mood, uncontrollable worry, and suicidality holds clinical importance for understanding the interplay between depression and anxiety and the risk of suicidality. Repetitive, perseverative negative thinking has been found to be a potential pathway perpetuating the relationship between depression and anxiety (Everaert & Joormann, 2019). This maladaptive thinking style not only maintains the symptoms of depression and anxiety but may also increase morbid thinking tendencies. Additionally, guilt (PHQ6), i.e., the feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, was most strongly connected to feeling afraid (GAD-7). In line with previous literature (Blake et al., 2018), our results supported the idea that dysfunctional thinking or cognitive distortion serves as one of the transdiagnostic underpinnings of depression and anxiety. The findings on bridge symptoms could inform future development of transdiagnostic prevention and intervention programs targeting common mental problems in adolescents. Compared to traditional disorder-specific treatment protocols, a transdiagnostic approach may potentially offer greater cost-effectiveness in managing comorbid psychopathology.

The current study revealed that about 27.69 % of adolescents reported some level of suicidality. Psychiatric problems, such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia, are known risk factors for suicidality (Eikelenboom et al., 2019; Hua et al., 2024). Using a flow network approach, the current study further untangled the relationships between suicidality and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in adolescents. Notably, all identified bridge symptoms, except for fatigue (PHQ4), were directly connected to suicidality (PHQ9). This observation aligned with the findings from the study conducted by Sun et al. (2024), who reported that sad Mood (PHQ2) and guilt (PHQ6) were directly linked to suicidality in a symptom network of insomnia and depression based on a sample of mental health professionals who recovered from COVID-19. Similarly, Xu et al. (2024) found that sad mood (PHQ2), sleep disturbances (PHQ3), and guilt (PHQ6) were directly connected to suicidality in the symptom network of depression and anxiety in adolescents. Despite differences in symptom networks and study samples, depressive mood and guilt or worthlessness consistently showed direct strong connections with suicidality across studies. Taken together, the findings provided important implications, suggesting that addressing these bridge symptoms could potentially reduce the risk of suicidality among adolescents. In this context, research has shown that CBT-I, which directly targets sleep problems, could help prevent suicidal ideation (Chan et al., 2022). Therefore, addressing sleep problems through prevention and timely intervention may be an effective strategy to reduce suicidality in young people.

Previous research has found that female sex and eveningness were associated with depression, anxiety, and insomnia at the construct level (Cheung et al., 2023; Ohannessian et al., 2017; Salk et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). Although a higher proportion of females and adolescents with higher eveningness reported symptoms of these psychiatric conditions in general, the network comparison tests in the present study did not reveal structure and global strength differences across genders or chronotypes. These findings may suggest that the activation of these psychiatric conditions and interconnections of psychopathology within depression, anxiety, and insomnia are similar across these demographic and chronotype groups. This observation was consistent with previous network analysis conducted in adults (Bai et al., 2022). Collectively, the findings may suggest that treatments should target the common underlying mechanism regardless of gender or chronotype. Further research may explore if any other factors (e.g., cultural and contextual variables, comorbid physical health conditions, concurrent treatments) could potentially affect the network structure.

Several limitations need to be noted when interpreting the findings. First, the causal association between symptoms could not be addressed due to the cross-sectional design. Future studies could utilise a longitudinal design to examine the dynamic network model. Second, self-administered screening tools were used to assess depressive, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms. Clinical interview tools could be employed when assessing the stability of symptom networks in adolescents who meet a clinical diagnosis of interest. Third, the analysis was based on the sample recruited from the community, which might limit the generalisability of the findings to the clinical samples in adolescents. However, our findings demonstrated some consistent results with those of previous studies conducted in different general or at-risk populations. Fourth, the study did not measure variables related to the pandemic. Our data collection was conducted in 2023 when schools were not suspended, although it partially overlapped with the ongoing pandemic. Finally, whilst sleep deprivation is often associated with insomnia and mental health, we did not capture and include this factor in the current network model. Future studies could extend the network model by incorporating subjective and objective sleep parameters (e.g., sleep duration).

To conclude, the present study identified symptoms in the somatic (i.e., fatigue, sleep disturbances), affective (sadness, worthless or guilt), and cognitive (i.e., uncontrollable worry) domains with important transdiagnostic implications in the context of comorbidity of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in adolescents. Moreover, it elucidated how individual symptoms of these conditions may contribute to suicidality among adolescents. The findings may have implications for future clinical practice and research in developing transdiagnostic preventive or interventional programmes for common mental problems in adolescents.

YKW reports personal fees from Eisai Co, Ltd, for delivering a lecture and sponsorship from Lundbeck HK Ltd and Aculys Pharma, Japan. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the schools and students who participated in the study.

Declaration of Interest

YKW reports personal fees from Eisai Co, Ltd, for delivering a lecture and sponsorship from Lundbeck HK Ltd and Aculys Pharma, Japan. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by General Research Fund [grant number: Ref. 17613820], Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong SAR, China.