The Sexual Cognitions Checklist (SCC) is the only measure that distinguishes and assesses both positive (PSC) and negative sexual cognitions (NSC). This study aimed to deepen the psychometric properties of its Spanish version by testing invariance, reliability, differences in frequency, associations with sexual functioning in solitary masturbation and sexual relationships and presenting standard scores.

MethodA total of 2004 Spanish cisgender heterosexual adults (48.1% men, 51.9% women) aged 18 to 79 years (M = 38.23; SD = 13.70), distributed across age groups (18–34, 35–49 and 50 or older) participated. Analyses included measurement invariance, McDonald’s omega, MANCOVAs, correlations, partial correlations, and regression models. Norms for positive sexual cognitions were generated by gender and age.

ResultsStrict invariance was confirmed across educational level, relationship status, and relationship length, and partial strict invariance for gender on both the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC scales. Age showed strict invariance in the SCC-PSC scale and configural in the SCC-NSC scale. The subscales showed good internal consistency. Frequency differences emerged, notably by gender, with men scoring higher in positive and women in negative sexual cognitions. Positive sexual cognitions were positively associated with sexual functioning, negative ones showed negative and weaker associations.

ConclusionsThe Spanish SCC version demonstrates reliability of its scores and provides sources of validity evidence for the interpretation of its scores, including associations with sexual functioning and measurement invariance across groups, enabling group comparisons. The availability of norms for positive sexual cognitions further supports its application in clinical settings. Future studies should include diverse populations and individuals with diagnosed sexual dysfunctions.

Sexual fantasies have been defined as “any mental imagery that is sexually arousing or erotic to the individual” (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995, p. 470). Their association with sexual desire or interest (Ruiz-Zorrilla et al., 2025) and sexual arousal (Walton & Bhullar, 2018) justifies their study to better understand various dimensions of sexual health, such as sexual functioning (Moyano et al., 2016) and sexual violence (Birke et al., 2024). Sexual fantasies constitute a fundamental aspect of human sexuality and are experienced by most individuals (Moyano & Sierra, 2014).

Prior research has identified several factors associated with sexual fantasies. Men generally report more frequent fantasies than women (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Renaud & Byers, 1999), and differ in content, with men favoring domination fantasies and women reporting more romantic and submissive themes (Joyal, 2017; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025). Age also plays a role, as both the frequency and variety of sexual thoughts tend to decline across the lifespan (Lehmiller & Gormezano, 2023). Relationship factors are relevant as well: being in a romantic relationship may shape the content of sexual fantasies (Hicks & Leitenberg, 2001), with intimacy-oriented fantasies more common in partnered contexts, and exploratory, sadomasochistic, and impersonal content more linked to solitary activity (Moyano et al., 2016). Moreover, relationship length shapes sexual dynamics, with changes in satisfaction and commitment influencing fantasy patterns over time (Meuwly & Schoebi, 2017). Accordingly, both the frequency and content vary across the course of the relationship (Hicks & Leitenberg, 2001), possibly influenced by changes in age and relational development. Higher educational levels have been associated to greater fantasy capacity (Pérez-González et al., 2011) and fewer negative emotions surrounding erotic thoughts Nimbi et al., 2023b). Sexual cognitions are closely related to sexual functioning. A higher frequency of sexual fantasies is generally associated with better sexual functioning (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Nimbi et al., 2023a; Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025), while their reduction or absence constitutes a diagnostic criterion for sexual desire and arousal disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Based on this evidence, our study examines gender, age, relationship status, relationship length, educational level, and sexual functioning as key variables. These variables can be organized within Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994), which has been applied to sexuality research in areas such sexual satisfaction (Calvillo et al., 2020; Henderson et al., 2009; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2016), subjective orgasm experience (Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2020) and teenage sexual activity (Corcoran, 2000). In this framework, personal factors like gender, age and sexual functioning fall within the microsystem; interpersonal variables such as relationship status, duration and sexual functioning in partnered sexual contexts pertain to the mesosystem; and cultural variables such as education can be situated between the exosystem and macrosystem.

Sexual fantasies are generally conceptualized as pleasurable and voluntary thoughts, but these can sometimes be experienced as aversive. Renaud and Byers (2001) distinguish between positive sexual cognitions (PSC) and negative sexual cognitions (NSC). Although both can elicit sexual arousal, PSC are acceptable, pleasant, and ego-syntonic, aiming to enhance sexual sensations, whereas NSC are unacceptable, unpleasant, and ego-dystonic (Renaud & Byers, 2020). PSC have been associated with good sexual adjustment (Renaud & Byers, 2001) and, more specifically, with good sexual functioning (Byers et al., 2013; Moyano et al., 2016). Conversely, when controlling PSC frequency, NSC have not been linked to sexual adjustment (Renaud & Byers, 2001) or sexual functioning (Moyano et al., 2016).

Although several scales exist to measure sexual fantasies frequency, the ability to distinguish between PSC and NSC is unique to the Sexual Cognitions Checklist (SCC; Renaud & Byers, 1999). This scale includes 56 sexual cognitions, that can be classified as positive or negative by individuals of any gender identity and sexual orientation (see Renaud & Byers, 2020). In Spain, Moyano and Sierra (2012) developed a revised version of the original scale, consisting of only 28 items, grouped into four content-based subscales: Intimate (i.e., thoughts related to the pursuit of pleasure and enjoyment through deep commitment to a sexual partner), Exploratory (i.e., thoughts related to the search for sexual excitement through variety), Sadomasochistic (i.e., thoughts related to sexual domination or submission), and Impersonal (i.e., sexual thoughts involving fetishes or inanimate elements devoid of emotional connection). This version of the SCC highlights both the multidimensionality of PSC and NSC and the significant correlation between these types of thoughts (ranging from .27 to .69). Additionally, it emphasizes the positive association of PSC with a favorable attitude toward sexual fantasies and the capacity for sexual daydreaming. In contrast, these variables are either unrelated to or negatively associated with NSC (Moyano & Sierra, 2012). These features make the SCC a highly useful scale in both clinical and research settings.

Currently, measurement invariance is a key requirement for any sexuality scale (e.g., Lin et al., 2024; Paquette et al., 2025; Sierra et al., 2025), that is, to guarantee that the scale operates similarly across groups (Byrne et al., 1989). The analysis of similarities and differences between groups (e.g., based on gender, age, sexual orientation, culture, etc.) is common in research on sexual fantasies (see Lehmiller & Gormezano, 2023). However, it is concerning that invariant measures are rarely used for such comparisons, which can lead to significant biases in the conclusions drawn. Therefore, in response to this concern, we propose measurement invariance testing to evaluate the assumption that SCC operate similarly across groups.

The current study aims to delve into the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the SCC (Moyano & Sierra, 2012)—specifically its PSC and NSC scales—by providing new evidence of reliability for its scores and sources of validity evidence for their interpretation. Following established guidelines (e.g., Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019; Sireci & Benítez, 2023), we set the following goals: (1) to examine measurement invariance by gender, age, educational level, relationship status, and relationship length; (2) to examine reliability; (3) to compare the frequency of PSC and NSC across groups; and (4) to analyze the explanatory capacity of PSC and NSC in relation to sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication in the contexts of solitary masturbation and sexual relationships. Finally, to enhance the SCC’s clinical utility, standardized scores are provided. Based on previous studies, we propose the following hypotheses: (1) the SCC will demonstrate measurement invariance by gender, age, educational level, relationship status, and relationship length (Moyano & Sierra, 2012); and (2) PSC will be positively associated with sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication, whereas NSC will either be negatively associated with these variables or show no significant relation with sexual functioning (Moyano et al., 2016).

MethodParticipantsThe sample was obtained using a non-probabilistic sampling approach with age quotas (18–34 years old; 35–49 years old; and 50 years old or older). A total of 2004 cisgender adults (48.1% men and 51.9% women) aged 18 to 79 years (M = 38.23; SD = 13.70), with a mean relationship length of 155.56 months (SD = 144.01), were included. This sample size allows us to work at a 97% confidence level with a 3% estimation error. The inclusion criteria were holding Spanish nationality and having sexual relationships exclusively with people of the opposite sex. The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Note. Percentages were calculated based on the number of valid responses for each item. Sample sizes may vary due to missing responses or not applicable value.

Sociodemographic and Sexual History Questionnaire. This instrument collects information on sex assigned at birth, gender, age, type of sexual relationships (i.e., exclusively heterosexual or exclusively homosexual), nationality, educational level, current relationship status, and relationship length. It also assesses, independently, whether participants have ever engaged in solitary masturbation and sexual relationships, as well as whether they have engaged in each of these activities during the past year.

Spanish version of the Sexual Cognitions Checklist (SCC; Renaud & Byers, 1999, 2020) by Moyano and Sierra (2012). It assesses the frequency, content, and valence of sexual cognitions through 28 items answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (I’ve never had this thought) to 6 (I’ve had -have- this thought frequently during the day). Each sexual cognition was formulated both as a positive thought (i.e., acceptable and pleasant) and as a negative thought (i.e., unacceptable, upsetting, and unpleasant), with participants reporting its frequency. The SCC comprises four subscales referring to four types of sexual cognitions: Intimate (e.g., “Having intercourse with a loves partner”), Exploratory (e.g., “Having sex with two other people at the same time”), Sadomasochistic (e.g., “Being forced to do something sexually”), and Impersonal (e.g., “Being excited by material or clothing”), with higher scores indicating more frequency of them. The scale’s scores and their interpretation are supported by accumulated evidence of reliability and sources of validity evidence, both in the original version and in the Spanish adaptation. Specifically, the Spanish version demonstrated internal consistency coefficients ranging from .67 to .87 in PSC subscales, and from .66 to .86 in NSC subscales. Additionally, sources of validity evidence for the interpretation of the scale's scores have been provided based on their relationship with other variables (Moyano & Sierra, 2012, 2013, 2014).

Spanish version of the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX; McGahuey et al., 2000) by Sánchez-Fuentes et al. (2019). This instrument assesses sexual function in both masturbation and sexual relationship contexts through a 6-point Likert scale (1 = hyperfunction; 6 = hypofunction). The scale comprises five items to assess sexual desire, sexual arousal, penile erection/vaginal lubrication, ability to reach orgasm, and satisfaction with orgasm. Higher scores indicate better sexual function because the scores were inverted for clarity. The Spanish version’s score have demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha =0.81 for men and .79 for women), along with sources of validity evidence for their interpretation based on their relationships with theoretically related and unrelated constructs. Participants completed the ASEX in two different contexts: solitary masturbation and sexual relationships. The items related to orgasm were not considered in this study. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients obtained were .65 and .75 for men in the contexts of masturbation and sexual relationships, respectively, and .76 and .86 for women.

ProcedureParticipants were recruited between October 2023 and September 2024 through an online questionnaire designed using LimeSurvey® software. The survey link was disseminated via email, virtual platforms, and social networks (e.g., X®, Instagram®, Telegram® or Reddit®) using both regular posts and promoted advertisements. Several associations and groups with diverse characteristics (e.g., student associations, senior citizens' associations or interest-based groups) were contacted. Posters were created and distributed to these groups and displayed in educational and social centers, public spaces, and leisure venues to broaden reach. These dissemination strategies enabled the collection of a large, heterogeneous sample of adults from across Spain.

To access the questionnaire, participants had to complete a CAPTCHA based on a random mathematical operation to prevent automatic responses. Participants were then asked to read and accept, if they agreed, the informed consent form, which detailed the study's nature, objectives, implications, confidentiality, and data anonymity. Each section of the questionnaire began with reinforced instructions and illustrative examples to ensure proper understanding. For quality control purposes, a control item requiring consistent responses was included, and the data were thoroughly screened, excluding anomalous or inconsistent entries. Response time was monitored following quality control recommendations (Huang et al., 2012), with participants taking an average of 20 min to complete the survey. The survey was designed to be completed in a single session, helping to minimize inconsistencies due to temporal or situational variations. Participation was voluntary, revocable, and without compensation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research (CEIH) of the University of Granada (reg. no. nº 3150/CEIH/2023).

Finally, survey responses (N = 12,555) were filtered to retain only those participants who provided informed consent to participate in the study (N = 7146), met the eligibility criteria (N = 5405), completed the initial sociodemographic section (N = 2952), responded attentively to the control item (N = 2830), and answered: (a) all items of the positive scale of the SCC (SCC-PSC; N = 2004); (b) all items of the negative scale of the SCC (SCC-NSC; N = 1659); and (c) all items of the SCC and the ASEX in both sexual contexts (N = 1331).

Data analysisTo address missing data, an algorithm for nonparametric distributions was applied, generating a random forest model for each variable. The factorial invariance of the SCC scores was then examined separately by gender (men, women), age (18–34 years old, 35–49 years old, ≥50 years old), educational level (non-university studies, university studies), relationship status (partnered, not partnered), and relationship length (<20 years, ≥20 years). These analyses were conducted in R® (version 4.4.2; R Core Team, 2024) with the RStudio® interface (version 2024.09.1 + 394; Posit Team, 2024), using the missForest package (version 1.5; Stekhoven & Bühlmann, 2012) for missing data imputation and the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) for measurement invariance analysis. The Weighted Least Squares Mean-adjusted (WLSM) estimator, a robust variant of the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) method, was used. The following fit indices and recommended thresholds were considered to determine good comparative fit: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) above .90 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Factorial invariance was analyzed progressively across four levels: configural, metric, scalar, and strict, applying partial invariance analysis when deemed necessary. The parameters to be freed in these analyses were selected based on the modification indices, which estimate the reduction in χ2 if a given constraint is lifted. Following the recommendations, a change in CFI of .01 or greater compared to the previous model indicated the adoption of the least restrictive level (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). However, for metric invariance, a slightly more relaxed criterion was applied, considering decreases of ≥ .02 in CFI as acceptable (Rutkowski & Svetina, 2014). Subsequently, McDonald’s omega (ω) was calculated using the Psych package (version 2.4.12; Revelle, 2024) to assess the reliability of the scores for each subscale of PSC and NSC by gender.

In accordance with Moyano et al. (2016), due to the differing number of items per subscale, we calculated the mean scores separately for each PSC and NSC subscale. These mean scores were used for all analyses except for the standard scores, where the overall dimensions were considered. Additionally, we calculated the mean scores of the subscales excluding the non-invariant items for gender, and these were used in the analyses of differences between men and women. Using MANCOVA, frequencies of PSC and NSC subscales were compared between groups based on the variables where the measurement invariance was established, including the frequencies of the other types of cognition (i.e., PSC or NSC) as covariates, since they are the main predictor of their respective overall frequencies (Moyano & Sierra, 2013). Each MANCOVA was conducted independently for each variable. The following analyses were performed separately for men and women. First, bivariate correlations were calculated between PSC and NSC subscales. Next, partial correlations were conducted separately for PSC and NSC with sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication across the contexts of solitary masturbation and sexual relationships, controlling for the overall frequency of the other subscales (NSC when analyzing PSC subscales and vice versa). Subsequently, regression models using the enter method were calculated to determine the explanatory power of the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC subscales on the sexual function components studied (i.e., sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication) in both sexual contexts. Finally, SCC-PSC norms were calculated differentiating by gender and age groups. The above analyses were performed with IBM® SPSS® v.28.

ResultsSources of validity evidence of internal structureMeasurement invarianceMeasurement invariance was tested independently across gender, age, educational level, relationship status, and relationship length for the four-factor model of the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC scales, separately. The results are shown in Table 2.

Measurement invariance of the sexual cognitions checklist.

| SCC-PSC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariance model | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | ΔCFI/ΔRMSEA | Invariance? | Non-invariant items | |

| Gender (N = 2004; n men = 964; n women = 1040) | ||||||||

| Configural | 6941.592 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .948 | .943 | .065 [.064, .067] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | ||||||||

| Full | 6248.671 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .937 | .933 | .069 [.067–.071] | .011/.004 | Yes++ | ||

| Partial | 6063.169 (711)⁎⁎⁎ | .940 | .936 | .068 [.066, .069] | .008/.003 | Yes | PSC17+ | |

| Scalar (vs. metric partial) | ||||||||

| Full | 7740.732 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .919 | .916 | .076 [.075, .078] | .019/.008 | No | ||

| Partial | 6676.940 (733)⁎⁎⁎ | .932 | .930 | .070 [.069, .072] | .008/.002 | Yes | PSC9‡; PSC17+‡ | |

| Strict (vs. scalar partial) | ||||||||

| Full | 8022.597 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .915 | .915 | .077 [.075, .078] | .014/.005 | No | ||

| Partial | 6997.962 (761)⁎⁎⁎ | .928 | .928 | .072 [.070, .073] | .004/.002 | Yes | PSC9‡; PSC17+‡ | |

| Age (N = 2004; n 18–34y = 892; n 35–49y = 636; n ≥ 50y = 476) | ||||||||

| Configural | 7113.780 (1032)⁎⁎⁎ | .952 | .948 | .065 [.064, .067] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 5611.282 (1080)⁎⁎⁎ | .947 | .944 | .065 [.063, .066] | .005/.000 | Yes | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 6216.649 (1128)⁎⁎⁎ | .940 | .939 | .067 [.066, .069] | .007/.002 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 6401.106 (1184)⁎⁎⁎ | .938 | .940 | .067 [.065, .068] | .002/.000 | Yes | ||

| Educational level (N = 2004; n university studies = 1484; n non-university studies = 520) | ||||||||

| Configural | 7467.323 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .947 | .942 | .067 [.066, .069] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 5847.812 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .945 | .941 | .066 [.065, .068] | .002/.001 | Yes | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 5964.712 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .944 | .942 | .066 [.064, .067] | .001/0.000 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 5974.532 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .944 | .944 | .065 [.063, .066] | .000/.001 | Yes | ||

| Relationship status (N = 1994; n partnered = 1472; n not partnered = 522) | ||||||||

| Configural | 7287.527 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .947 | .942 | .067 [.066, .068] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 5782.504 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .945 | .942 | .066 [.065, .068] | .002/.001 | Yes | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 5951.020 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .943 | .942 | .066 [.065, .068] | .002/.000 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 5973.149 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .943 | .943 | .065 [.064, .067] | .000/.001 | Yes | ||

| Relationship length (N = 1468; n < 20y = 1067; n ≥ 20y = 401) | ||||||||

| Configural | 5698.895 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .946 | .941 | .068 [.067, .070] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 4654.177 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .942 | .938 | .068 [.066, .070] | .004/.000 | Yes | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 4888.803 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .938 | .937 | .069 [.067, .071] | .004/.001 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 4935.022 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .938 | .938 | .068 [.066, .070] | .000/.001 | Yes | ||

| SCC-SNC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariance model | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | ΔCFI/ΔRMSEA | Invariance? | Non-invariant items | |

| Gender (N = 1659; n men = 832; n women = 827) | ||||||||

| Configural | 3705.809 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .951 | .946 | .045 [.044, .047] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | ||||||||

| Full | 3387.466 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .930 | .926 | .049 [.047, .050] | .021/.004 | No | ||

| Partial | 3279.086 (711)⁎⁎⁎ | .936 | .931 | .047 [.046, .049] | .015/.002 | Yes++ | NSC13+ | |

| Scalar (vs. metric partial) | ||||||||

| Full | 3718.252 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .920 | .917 | .051 [.049, .052] | .016/.004 | No | ||

| Partial | 3565.357 (734)⁎⁎⁎ | .927 | .924 | .049 [.048, .051] | .009/.002 | Yes | NSC13+; NSC4‡ | |

| Strict (vs. scalar partial) | ||||||||

| Full | 3813.416 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .917 | .918 | .051 [.049, .052] | .010/.002 | No | ||

| Partial | 3647.898 (762)⁎⁎⁎ | .925 | .925 | .049 [.047, .050] | .002/.000 | Yes | NSC13+; NSC4‡ | |

| Age (N = 1659; n 18–34y = 746; n 35–49y = 531; n ≥ 50y = 382) | ||||||||

| Configural | 4175.696 (1032)⁎⁎⁎ | .947 | .942 | .048 [.047, .050] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 3915.759 (1080)⁎⁎⁎ | .905 | .900 | .054 [.052, .056] | .042/.006 | No | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 4111.525 (1128)⁎⁎⁎ | .899 | .898 | .054 [.052, .056] | .006/.000 | No | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 4335.708 (1184)⁎⁎⁎ | .892 | .897 | .054 [.053, .056] | .007/.000 | No | ||

| Educational level (N = 1659; n university studies = 1254; n non-university studies = 405) | ||||||||

| Configural | 3806.174 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .951 | .947 | .045 [.044, .046] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 3315.435 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .933 | .929 | .048 [.046, .049] | .018/.003 | Yes++ | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 3402.582 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .932 | .930 | .047 [.046, .049] | .001/.001 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. acalar) | 3440.940 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .931 | .932 | .047 [.045, .048] | .001/.000 | Yes | ||

| Relationship status (N = 1651; n partnered = 1208; n not partnered = 443) | ||||||||

| Configural | 3819.178 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .946 | .941 | .046 [.045, .048] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 2975.796 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .943 | .939 | .045 [.043, .046] | .003/.001 | Yes | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 3013.300 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .943 | .941 | .044 [.043, .046] | .000/.001 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs.scalar) | 3052.648 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .942 | .943 | .044 [.042, .045] | .001/.000 | Yes | ||

| Relationship length (N = 1206; n < 20y = 894; n ≥ 20y = 312) | ||||||||

| Configural | 2965.215 (688)⁎⁎⁎ | .963 | .959 | .044 [.042, .046] | Yes | |||

| Metric (vs. configural) | 2504.289 (712)⁎⁎⁎ | .946 | .944 | .045 [.043, .047] | .017/.001 | Yes++ | ||

| Scalar (vs. metric) | 2586.546 (736)⁎⁎⁎ | .944 | .942 | .045 [.043, .047] | .002/.000 | Yes | ||

| Strict (vs. scalar) | 2644.558 (764)⁎⁎⁎ | .942 | .943 | .045 [.043, .047] | .001/.000 | Yes | ||

Note. PSC = Positive Sexual Cognitions; NSC = Negative Sexual Cognitions; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CI = Confidence Interval; Δ = absolute change value between consecutive invariance models;.

The results supported strict measurement invariance of SCC-PSC scores across age, RMSEA = .067, 95% CI [.065, .068], CFI = .938; educational level, RMSEA = .065, 95% CI [.063, .066], CFI = .944; relationship status, RMSEA = .065, 95% CI [.064, .067], CFI = .943; and relationship length, RMSEA = .068, 95% CI [.066, .070], CFI = .938. For gender, partial strict invariance was established, RMSEA = .072, 95% CI [.070, .073], CFI = .928, by relaxing the intercepts for item 9 “Engaging in sexual activity contrary to my sexual orientation (e.g., homosexual or heterosexual)” (Participar en una actividad sexual contraria a mi orientación sexual [p. e., homosexual o heterosexual]) and both the factor loadings and intercepts for item 17 “Being whipped of spanked” (Ser azotado/a o golpeado/a en el trasero)”, resulting in an improved model fit.

For the SCC-NSC scores, the invariance tests showed full strict measurement invariance across educational level, RMSEA = .047, 95% CI [.045, .048], CFI = .931; relationship status, RMSEA = .044, 95% CI [.042, .045], CFI = .942; and relationship length, RMSEA = .045, 95% CI [.043, .047], CFI = .942. Similarly to the SCC-PSC, partial strict invariance was found for gender, RMSEA = .049, 95% CI [.047, .050], CFI = .925, after relaxing the factor loadings for item 13 “Having sex with a non-human object” (Tener sexo con un objeto inanimado [p. ej., muñeco/a hinchable]) and the intercepts for item 4 “Being pressured into engaging in sex” (Ser presionado/a mantener relaciones sexuales). For age, only configural invariance was achieved, RMSEA = .048, 95% CI [.047, .050], CFI = .947.

Correlations between SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC subscalesPositive correlations were observed between SCC-PSC subscales, ranging from .40 to .62 in men and .38 to .57 in women. Similarly, SCC-NSC subscales showed positive correlations, ranging from .25 to .73 in men and from .29 to .73 in women. The number of significant associations between SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC subscales was similar across both groups, with only two non-significant associations in women and six in men. Among the significant associations, values ranged from .10 to .31 in men and from .08 to .40 in women. Notably, the Intimacy subscale of the SCC-NSC showed the fewest associations in both groups. The detailed data can be found in Table 3.

Correlations between sexual cognitions checklist-PSC and sexual cognitions checklist-NSC subscales.

| Subscales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSC Intimate | – | .45⁎⁎ | .48⁎⁎ | .45⁎⁎ | .00 | .27⁎⁎ | .40⁎⁎ | .28⁎⁎ |

| 2. PSC Exploratory | .51⁎⁎ | – | .52⁎⁎ | .57⁎⁎ | .08* | .14⁎⁎ | .30⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ |

| 3. PSC Sadomasochistic | .40⁎⁎ | .47⁎⁎ | – | .38⁎⁎ | .14⁎⁎ | .19⁎⁎ | .21⁎⁎ | .19⁎⁎ |

| 4. PSC Impersonal | .48⁎⁎ | .62⁎⁎ | .42⁎⁎ | – | .02 | .11⁎⁎ | .20⁎⁎ | .12⁎⁎ |

| 5. NSC Intimate | −0.10 | .02 | .13⁎⁎ | .03 | – | .42⁎⁎ | .29⁎⁎ | .38⁎⁎ |

| 6. NSC Exploratory | .18⁎⁎ | .10* | .21⁎⁎ | .08 | .52⁎⁎ | – | .70⁎⁎ | .73⁎⁎ |

| 7. NSC Sadomasochistic | .31⁎⁎ | .14⁎⁎ | .15⁎⁎ | .14⁎⁎ | .25⁎⁎ | .60⁎⁎ | – | .72⁎⁎ |

| 8. NSC Impersonal | .17⁎⁎ | .07 | .21⁎⁎ | .07 | .47⁎⁎ | .73⁎⁎ | .60⁎⁎ | – |

Note. PSC = Positive Sexual Cognitions; NSC = Negative Sexual Cognitions. Values below the diagonal are based on male scores. Values above the diagonal are based on female scores.

McDonald’s omega values were obtained for men and women, respectively: PSC Intimate (ω = .92, ω = .93), PSC Exploratory (ω = .88, ω = .87), PSC Sadomasochistic (ω = .86, ω = .87), PSC Impersonal (ω = .60, ω = .64), NSC Intimate (ω = .90, ω = .85), NSC Exploratory (ω = .87, ω = .87), NSC Sadomasochistic (ω = .94, ω = .95), and NSC Impersonal (ω =0.68, ω = .68).

Sources of validity evidence in relation with other variablesDifferences of the SCC subscales according to gender, age, educational level, relationship status and relationship lengthAll five MANCOVAs conducted for the SCC-PSC revealed significant main effects. The Intimate, Exploratory, and Sadomasochistic SCC-NSC subscales emerged as significant multivariate covariates across all analyses (all p < .05), whereas Impersonal SCC-NSC subscale did not show a significant effect in any case (all p > .05). Specifically, gender had a main effect on PSC dimensions, Pillai’s trace = 0.17; F(4, 1322) = 67.96; p < .001; η²ₚ = .17, with men scoring significantly higher across all PSC dimensions. Age also had a significant main effect, Pillai’s trace = 0.14; F(4, 1321) = 24.16; p < .001; η²ₚ = .07, with significant differences observed in all PSC dimensions. Pairwise comparisons further examined these differences, as detailed in Table 4. For education level, the MANCOVA revealed a significant main effect, Pillai’s trace = 0.01; F(4, 1322) = 3.51; p = .007; η²ₚ = .01. Significant differences were observed only in the impersonal PSC dimension, with individuals with non-university education scoring higher. Regarding relationship status, a significant main effect was observed, Pillai’s trace = 0.02; F(4, 1322) = 5.26; p < .001; η²ₚ = .02, with significant differences only in the exploratory PSC dimension, where not partnered individuals scored higher. Finally, relationship length showed a significant main effect, Pillai’s trace = .06; F(4, 1007) = 15.88; p < .001; η²ₚ = .06. Significant differences were found in the intimate, sadomasochistic, and impersonal PSC dimensions. The group with a relationship length of less than two decades scored higher in the intimate and sadomasochistic PSC dimensions, while those in relationships lasting 20 or more years scored higher in the impersonal PSC dimension. The full results of the MANCOVA analyses are presented in Table 4.

Differences between sexual cognitions checklist-PSC and sexual cognitions checklist-NSC subscales according to gender, age, educational level, relationship status and relationship length.

Note. PSC = Positive Sexual Cognitions; NSC = Negative Sexual Cognitions; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; F = F-statistic; p = level of significance; η²ₚ = partial eta-squared.

A similar set of independent MANCOVAs was conducted for the SCC-NSC, examining only the effects of the variables for which measurement invariance was met (i.e., all variables except age). Unlike the previous case, all subscales of the SCC-PSC were significant multivariate covariates across all MANCOVAs (all p < .05), except for the Impersonal PSC subscale, where no significant effect was found in the MANCOVA examining differences by gender, Pillai’s trace = 0.00; F(4, 1322) = 1.23; p = .296; η²ₚ = .00. Gender had a significant main effect on NSC dimensions, Pillai’s trace = 0.06; F(4, 1322) = 19.99; p < .001; η²ₚ = .06, with women scoring significantly higher in the intimate, exploratory, and sadomasochistic NSC dimensions. For education level, although no significant multivariate effect was found, Pillai’s trace = 0.00; F(4, 1322) = 2.14; p = .074; η²ₚ = .00, univariate analyses showed significant differences in exploratory, sadomasochistic and impersonal NSC dimensions across education levels. Regarding relationship status variable, a significant main effect was observed, Pillai’s trace = 0.01; F(4, 1322) = 3.07; p = .016; η²ₚ = .01, with not partnered individuals scoring significantly higher in the intimate, exploratory, and impersonal NSC dimensions. Finally, relationship length had a significant main effect, Pillai’s trace = .03; F(4, 1007) = 6.40; p < .001; η²ₚ = .03. Significant differences were found in the four NSC dimensions, with individuals in relationships lasting two or more decades scoring higher in all cases. The complete results for these analyses can be found in Table 4.

Relation of SCC subscales with sexual functionAll positive associations were found between the SCC-PSC subscales and the variables of interest (i.e., sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication in both sexual contexts), whereas all negative associations were observed between the SCC-NSC subscales and these variables. Low positive correlations were observed between some SCC-PSC subscales and components of sexual function. SCC-NSC subscales showed weaker or no significant correlations, especially among men. Detailed correlation values are shown in Table 5.

Partial correlations between PSC and NSC subscales, and sexual desire, sexual arousal and penile erection/vaginal lubrication in solitary masturbation and sexual relationships.

| Men (N = 566) | Women (N = 765) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Context | |||||||||||

| Solitary masturbation | Sexual relationships | Solitary masturbation | Sexual relationships | |||||||||

| Subscales | Sexual desire | Sexual arousal | Penile erection | Sexual desire | Sexual arousal | Penile erection | Sexual desire | Sexual arousal | Vaginal lubrication | Sexual desire | Sexual arousal | Vaginal lubrication |

| PSC Intimate | .26⁎⁎ | .15⁎⁎ | .17⁎⁎ | .33⁎⁎ | .28⁎⁎ | .20⁎⁎ | .33⁎⁎ | .30⁎⁎ | .17⁎⁎ | .41⁎⁎ | .36⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ |

| PSC Exploratory | .23⁎⁎ | .15⁎⁎ | .02 | .11⁎⁎ | .09* | .01 | .21⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ | .08* | .17⁎⁎ | .16⁎⁎ | .06 |

| PSC Sadomasochistic | .17⁎⁎ | .12⁎⁎ | .10* | .09* | .10* | .06 | .19⁎⁎ | .17⁎⁎ | .11⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ | .20⁎⁎ | .12⁎⁎ |

| PSC Impersonal | .26⁎⁎ | .21⁎⁎ | .06 | .13⁎⁎ | .14⁎⁎ | .07 | .22⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ | .09⁎⁎ | .18⁎⁎ | .16⁎⁎ | .06 |

| NSC Intimate | .01 | −.04 | −.04 | −.01 | .00 | .01 | −.08* | −.18⁎⁎ | −.15⁎⁎ | −.17⁎⁎ | −.20⁎⁎ | −.13⁎⁎ |

| NSC Exploratory | −.01* | −.11* | −.02 | −.03 | .01 | −.01 | −.11⁎⁎ | −.14⁎⁎ | −.11⁎⁎ | −.10⁎⁎ | −.15⁎⁎ | −.12⁎⁎ |

| NSC Sadomasochistic | −.16⁎⁎ | −.16⁎⁎ | −.03 | −.13⁎⁎ | −.09* | −.04 | −.12⁎⁎ | −.18⁎⁎ | −.11⁎⁎ | −.16⁎⁎ | −.18⁎⁎ | −.13⁎⁎ |

| NSC Impersonal | −.10* | −.10* | −.01 | −.02 | −.02 | .00 | −.12⁎⁎ | −.15⁎⁎ | −.10⁎⁎ | −.11⁎⁎ | −.11⁎⁎ | −.09⁎⁎ |

Note. PSC = Positive Sexual Cognitions; NSC = Negative Sexual Cognitions. Only participants who have masturbated alone and had heterosexual relationships in the last year are included.

Multiple regression models were used to examine the strength of the association between SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC subscales and components of sexual function (Table 6). In men, the explained variance for the solitary masturbation context was 9% for sexual desire, F(8, 557) = 7.93; p < .001, associated with Intimate (β = .17) and Impersonal (β = .14) subscales of SCC-PSC as well as the Sadomasochistic subscale (β = −.14) of SCC-NSC; 5 % for sexual arousal, F(8, 557) = 4.56; p < .001, associated with impersonal PSC dimension (β = .17) and the sadomasochistic NSC dimension (β = −.14); and 3% for penile erection, F(8, 557) = 3.11; p = .002, associated with intimate (β = .20) and exploratory (β = −.12) PSC dimensions. In the sexual relationships context, the explained variance was 10% for sexual desire, F(8, 557) = 9.09; p < .001, associated with intimate PSC dimension (β = .38) and the sadomasochistic NSC dimension (β = −.19); 8% for sexual arousal, F(8, 557) = 7.09; p < .001, associated with intimate PSC (β = .32) and the sadomasochistic NSC dimensions (β = −.14); and 4% for penile erection, F(8, 557) = 3.81; p < .001, associated with intimate (β = .26) and exploratory (β = −.14) PSC dimensions.

Multiple regression models for sexual function in men and women.

Note. PSC = Positive Sexual Cognitions; NSC = Negative Sexual Cognitions; B = non-standardized beta; SE = standard error; β = standardized beta; 95% CI = 95 % confidence interval; R2 = coefficient of determination; VIF = variance inflation factor. Only participants who have masturbated alone and had heterosexual relationships in the last year are included.

Among women, the regression models showed that, in the solitary masturbation context, sexual desire, F(8, 756) = 14.20; p < .001, was associated with intimate PSC dimension (β = .30), accounting for 12% of the explained variance. Similarly, sexual arousal, F(8, 756) = 14.08; p < .001, was associated with both the PSC and NSC intimate dimensions (β = .26; β = −.13), as well as the exploratory PSC (β = .10) and sadomasochistic NSC (β = −.15) dimensions, also explaining 12% of the variance. Finally, vaginal lubrication, F(8, 756) = 5.21; p < .001, was associated with the intimate PSC and NSC dimensions (β = .16; β = −.13), accounting for 4 % of the explained variance. In the sexual relationships context, the models accounted for 19 % of the explained variance in sexual desire, F(8, 756) = 23.04; p < .001, with significant contributions from both intimate PSC and NSC dimensions (β = .42; β = −.14) and sadomasochistic NSC dimension (β = −.16). Sexual arousal, F(8, 756) = 18.53; p < .001, was associated with same three dimensions (β = .36; β = −.16; β = −.18, respectively), explaining 16% of the variance. Lastly, vaginal lubrication, F(8, 756) = 6.66; p < .001, was associated with PSC and NSC intimate dimensions (β = .24; β = −.09), and sadomasochistic NSC dimension (β = −.12), accounting for 6% of the explained variance.

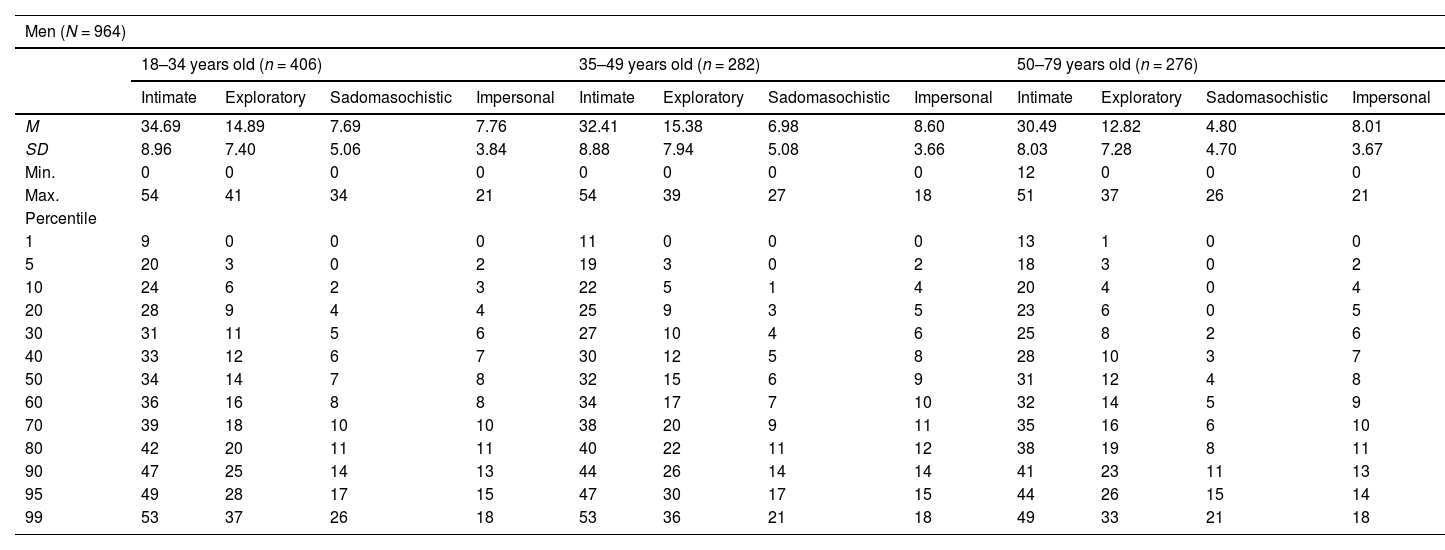

Standard scoresThe norms of the SCC were established using three age groups (18–34 years old, 35–49 years old, and 50 years or older), which have been employed in previous sexual health measurement instruments (e.g., Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2019; Sierra et al., 2020, 2024). The standard scores for SCC-NSC are not provided due to low data variability. Table 7 and Table 8 present the standard scores for SCC-PSC differentiated by gender and age.

Standard scores of the Sexual Cognitions Checklist-PSC in men across different age groups.

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Min. = minimum; Max. = maximum.

Standard scores of the Sexual CognitionsChecklist-PSC in women across different age groups.

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Min. = minimum; Max. = maximum.

This study examined the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the SCC (Moyano & Sierra, 2012), expanding the available evidence supporting the reliability and sources of validity evidence of its scores and interpretation across multiple domains. Specifically, the findings indicate that the SCC exhibits measurement invariance across several demographic variables—with partial invariance observed across gender—for SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC scales. Significant differences across SCC subscales are observed according to sociodemographic characteristics, particularly gender. Furthermore, associations are found between the different subscales and sexual functioning for both men and women. Overall, these results underline the SCC’s psychometric properties, consolidating it as a valuable tool for both researchers and clinicians working in the field of sexual health.

Regarding the first objective, the examination of measurement invariance across gender, age, educational level, current relationship status, and relationship length, the results indicate mostly strictly equivalent measures across the different subgroups, suggesting that the SCC is an instrument whose measures would not introduce bias in comparisons between different sociodemographic groups. Strict measurement invariance was achieved for both the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC scales across all sociodemographic variables, except for age in the SCC-NSC scale, for which only configural invariance was established. This finding precludes valid comparisons of NSC scores across age groups.

Concerning measurement invariance by gender, partial invariance was applied by releasing the items with the highest modification indices (items 9 and 17 in the SCC-PSC, and items 4 and 13 in the SCC-NSC). The positive sexual cognition “Engaging in sexual activity contrary to my sexual orientation” (Participar en una actividad sexual contraria a la orientación sexual, item 9) may reflect gender-based differences in sexual experimentation. Joyal et al. (2015) reported that fantasies about having homosexual activities were more frequent in women than in men. Moreover, such behaviors may be more socially accepted among women, whereas men tend to face higher levels of homophobia (Diamond, 2008). As Campbell (1995) argued, within the male gender script, “to be heterosexual, above all, is not to be homosexual”, which may lead many men to avoid behaviors that could call their masculinity into question. In relation to the positive sexual cognition “Being whipped of spanked” (Ser azotado/a o golpeado/a en el trasero, item 17), the higher prevalence of submission-related fantasies among women (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995) may facilitate its integration as a positive sexual thought, whereas men, who report more domination fantasies (Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025), may perceive the positive framing of such a submissive act as distinctly feminine and/or unmasculine. Social norms and cultural conventions shape sexuality by promoting active or dominant roles in men and more passive or receptive roles in women (Wiederman, 2015; Ziegler & Conley, 2016). The negative sexual cognition “Being pressured into engaging in sex” (Ser presionado/a mantener relaciones sexuales, item 4) may reflect women’s greater exposure to such experiences, given that men have been more frequently identified as perpetrators of sexual coercion (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2018). This differential experience may contribute to women being more sensitized to identifying this cognition as negative, even when it is not explicitly labeled as sexual violence (Brewer & Forrest-Redfern, 2022). In contrast, when men experience this thought, they may be more likely to downplay or normalize the experience, as they often do not perceive their own use of sexual pressure as coercive (Jozkowski et al., 2017). Finally, the negative sexual cognition “Having sex with a non-human object” (Tener sexo con un objeto inanimado [p.e., muñeco/a hinchable], item 13) may be perceived differently due to the specific example included in the item wording. The explicit mention of inflatable dolls, a type of sex doll, may trigger associations—linked to stereotypes or specific practices—that do not fully reflect the broader meaning encompassed by the expression “sex with an inanimate object.” There is an ongoing debate over whether the use of sex dolls may be harmful to women, as some theoretical literature frames them as expressions of patriarchal power and sexual objectification, potentially reinforcing sexism (Döring et al., 2020). This connotation may lead many women to experience this sexual thought more negatively—or at least differently—than men. Several studies have indicated that heterosexual men are the primary and potential users of sex dolls, employing them as masturbation aids or as substitutes for a human partner (DeMaris & McGovern, 2023; Peschka & Raab, 2022). Among this group, such use may be more normalized, contributing to a less negative interpretation of the discussed cognition.

The release of these four items (two positive and two negative) allowed strict invariance to be achieved across gender. Therefore, from a practical standpoint, these items should be excluded from comparisons of positive or negative sexual cognitions (as applicable) between cisgender heterosexual men and women.

The reliability analyses support the robustness of the scores of the Spanish version of the SCC, demonstrating satisfactory indices and confirming its internal consistency for SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC, in line with previous studies (Moyano & Sierra, 2012, 2013, 2014; Moyano et al., 2016). The correlation patterns among the various subscales support the internal structure of the SCC. As expected, the subscales of SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC exhibit stronger correlations with each other (moderate to high correlations) than with those of the other scale (very low to low correlations). These results reinforce both the conceptual distinction between positive and negative sexual cognitions, in line with the theoretical framework underlying the SCC (Renaud & Byers, 1999), and the association between these two types of cognitions (Moyano & Sierra, 2013).

Based on the levels of invariance obtained, the groups for which the measure showed invariance were compared. The results reveal significant differences in the frequency of most PSC dimensions (except for educational level and relationship status) and NSC, although with small effect sizes, except for those observed based on gender in the SCC-PSC dimensions, where men, compared to women, reported a higher frequency of sexual thoughts. This finding aligns with the accumulated evidence on gender differences in sexual fantasies (Leintenberg & Henning, 1995; Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Nimbi et al., 2023a; Renaud & Byers, 1999), related to more permissive sexual socialization for men than for women, reflected in the existence of sexual scripts and the sexual double standard (Ziegler & Conley, 2016). For example, men are granted more sexual freedom and are rewarded for showing sexual willingness, while women are socially reprimanded and punished if they behave in ways inconsistent with their gender (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021; Greene & Faulkner, 2005; Rudman & Fairchild, 2004). This gendered socialization is also reflected in the higher frequency of NSC reported by women in the intimacy, exploratory and sadomasochistic dimensions compared to men. The socialization of women includes, among other aspects, the promotion of abstinence, warnings about the consequences of female sexuality, and its condemnation (Ziegler & Conley, 2016), making it expected that, in contrast to men, women would experience NSC more frequently. Together, these findings reinforce the idea that the most pronounced differences are concentrated by gender, while other sociodemographic factors show more subtle associations that should be explored in greater detail in future research.

In the remaining comparisons, only the differences in PSC across age groups approached a medium effect size. A higher frequency of PSC was observed among younger individuals, particularly those in emerging adulthood (i.e., 18- to 29-year-old; Arnett, 2015), a developmental stage characterized by identity exploration (Arnett, 2000), the consolidation of sexual scripts (Thompson et al., 2020), and the formation of relationships marked by intense emotional closeness and desire (Meuwly & Schoebi, 2017). Additionally, a study with a Spanish sample reported higher exposure to and consumption of pornographic content among younger adults, with dominant themes involving domination, submission, and even sexual violence (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2023). An exception was found for impersonal PSC, which were more frequent among middle-aged and older adults compared to the youngest group, possibly due to a broader range of life and sexual experiences that may facilitate the development of such cognitions.

Sources of validity evidence for the score interpretations of the SCC are further supported by their observed associations with sexual functioning. In both men and women, intimate PSC emerged as the most consistent and relevant in this relationship, showing positive associations with all components of the sexual response in both masturbation and sexual relationships contexts, except for sexual arousal in the sexual relationships context in men. These results suggest that positively valenced sexual cognitions with intimate content are the most important for optimal sexual functioning. This finding is consistent with the fact that such thoughts represent the most frequently reported PSC in both men and women (Moyano & Sierra, 2012, 2014; Renaud & Byers, 1999; Ruiz-Zorrilla et al., 2025), and it is well established that a higher frequency of sexual fantasies is generally associated with better sexual functioning (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Nimbi et al., 2023a; Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025).

Shekarchi and Nimbi (2025) noted that, in women, the presence of negative emotions related to sexual fantasies is associated with lower sexual functioning and satisfaction. In line with this, among the women in our study, intimate negatively valenced sexual cognitions were negatively associated with sexual function in both contexts, except for sexual desire in the solitary masturbation context. This pattern aligns with the more specific and less varied nature of women’s sexual fantasies, which tend to center on emotional aspects such as romance and intimate relationships (Ellis & Symons, 1990; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025). For many women, sex is often closely tied to emotional intimacy, with emotional and relational aspects typically prioritized in sexual relationships (Birnbaum & Laser-Brandt, 2002; Regan & Dreyer, 1999). Accordingly, love or the expression of emotional closeness often represents a primary motivation for engaging in sexual activity, whereas men more commonly report reasons such as tension release or the pursuit of pleasure (Leigh, 1989). This suggests that intimate sexual cognitions may carry a particularly strong emotional weight for women—when experienced as positive, they enhance sexual functioning, but when imbued with negative emotion, they significantly impair it. In contrast, such cognitions appear to have a more limited impact among men, likely due to the lesser emphasis placed on emotional intimacy. Overall, the stronger emotional investment in sexual intimacy among women may help explain why negative valenced thoughts in this domain are especially detrimental to their sexual well-being. Moreover, if social or cultural pressures lead to the development of NSC in women, it is likely that these would arise precisely around the emotionally meaningful content they already fantasize about, such as intimacy. In this regard, it has been noted that men not only fantasize more frequently but also tend to perceive sexual fantasies as more acceptable for themselves than for women (Ziegler & Conley, 2016), which may contribute to a more negative evaluation of sexual thoughts among women.

In relation to exploratory sexual thoughts, their associations with sexual functioning are limited. In men, only exploratory PSC are negatively associated with erectile function in both masturbation and sexual relationships contexts, whereas in women, they are positively associated with sexual arousal in solitary masturbation context. Although these associations are weak and inconsistent across gender or sexual contexts, they may suggest that the exploratory content of PSC—linked to sexual novelty and variety—can have different implications depending on gender and sexual context. This dimension encompasses sexual thoughts related to group sex, partner swapping, or sexual activity in public spaces. In men, although this type of content may be initially associated with positive affect in the fantasy world or imagined scenarios typical of sexual fantasies, it may activate performance anxiety, a phenomenon which negatively affects their erectile capacity (Telch & Pujols, 2013). This anxiety, characterized by a focus on sexual performance and potentially leading to sexual dysfunction (McCabe, 2005), can be understood in terms of male competition and the avoidance of humiliation. Fleming et al. (2019) have described how men often feel pressured to maintain their reputation and demonstrate their masculinity through their sexual capabilities and prowess. Such pressure might extend to the experience of exploratory sexual thoughts, with their content potentially eliciting self-doubt about sexual competence. Conversely, the positive association observed between exploratory PSC and arousal in women during solitary contexts, such as masturbation, aligns with previous studies linking this type of fantasy to solitary sexual desire (Moyano et al., 2016; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2013). These thoughts may be related to increased arousal without necessarily translating into a parallel increase in sexual desire, due to the well-documented overlap between these two components of the female sexual response, widely reported in the literature (e.g., Brotto et al., 2009) and reflected in the recent revision DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Regarding the sadomasochistic dimension, only NSC show significant associations with sexual functioning, and these are consistently negative. This result was expected, given the nature of the thoughts involved, which focus on roles of dominance and submission and include potentially distressing items such as “forcing someone to have sex with me” or “being a sexual victim”. Among women, the most salient associations appear in the context of partnered sexual activity. This finding seems consistent with prior research showing that submission-related sexual fantasies are common in female sexuality (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Ziegler & Conley, 2016) and that women report more frequent negative cognitions involving submission than men (Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Renaud & Byers, 2006). While such content may be arousing in the realm of fantasy, it can evoke feelings of vulnerability or risk during real-life encounters, thereby interfering with sexual functioning. In contrast, in men, sadomasochistic NSC are negatively associated with both sexual desire and sexual arousal across contexts. Unlike women, men report a higher frequency of negative dominance-related cognitions (Moyano & Sierra, 2014; Renaud & Byers, 2005), which may be experienced as more disturbing due to the typically more explicit and visually charged content of male sexual thoughts (Ellis & Symons, 1990; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995). Additionally, recent sociocultural shifts, driven by movements such as #MeToo (Rentschler, 2018), may have contributed to greater male awareness and sensitivity regarding consent and sexual violence, even within the realm of fantasy, which could help explain the observed impairments in sexual functioning.

Finally, regarding impersonal sexual thoughts, significant associations were found only in men, specifically between PSC and sexual desire and sexual arousal in the context of masturbation. Moyano et al. (2016) had already noted that men fantasize more frequently than women about impersonal PSC and that this content seems important for solitary sexual activities. Given that these thoughts do not involve another person, it seems consistent that they would carry greater relevance in an individual context such as solitary masturbation. This pattern may also reflect the traditional male sexual script, in which sex is often less connected to emotional intimacy than it is for women, thereby facilitating greater sexual activation from this type of content, especially in solitary settings. Leigh (1989) reported that men more often cite pleasure, conquest, or tension relief as primary sexual motivations, whereas women are more likely to mention love or expressing emotional closeness, often delaying the initiation of sexual relationships until emotional intimacy has been established (Seal & Ehrhardt, 2003). In this sense, impersonal PSC may promote the emergence of sexual desire and sexual arousal without the need for emotional involvement or the risk of external evaluation, an aspect that may be particularly practical for men.

Notably, the more physiological component of the sexual response (i.e., penile erection/vaginal lubrication) showed the lowest levels of explained variance, suggesting a weaker connection to the sexual fantasy domain. While sexual thoughts may enhance desire or the subjective experience of general arousal, the onset of the physiological response might require that sufficient levels of those cognitive and affective states have already been reached. Thus, sexual fantasy does not necessarily lead to an observable genital response, this would occur only in specific situations and in response to certain types of sexual thoughts (e.g., intimate in both men and women, and exploratory and sadomasochistic in men and women, respectively). Our findings suggest that sexual cognitions, especially positive ones, may play a more prominent role in shaping desire and subjective arousal than in triggering purely physiological responses. Recognizing this distinction may be particularly useful in clinical contexts.

Our findings support the relevance of adopting an ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) to better understand sexual cognitions. The most pronounced differences were observed in relation to personal variables, particularly gender, followed by age. In contrast, interpersonal (i.e., relationship status and length) and cultural factors (i.e., educational level) were associated with more subtle group differences. This pattern highlights the relevance of considering sexuality as a multilayered phenomenon shaped by nested systems, where individual characteristics are most central, while relational and sociocultural contexts modulate their expression to varying degrees. However, when examining sexual functioning associations with sexual cognitions were similar in both solitary and partnered contexts—though slightly stronger in partnered context—suggesting that interpersonal variables may play a more relevant role than initially expected. Therefore, while gender remains the most salient differentiating factor, the potential influence of interpersonal and cultural variables should not be overlooked and warrants further investigation in future research.

In synthesis, we highlight that the Spanish version of the SCC (Moyano & Sierra, 2012) is an invariant measure by gender, educational level, relationship status, and relationship length (all at the strict level), and by age (strict level in SCC-PSC and configural in SCC-NSC), thus almost fully confirming our first hypothesis. Furthermore, the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC subscales were related to sexual function (i.e., sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication). Previous research has indicated that frequent and positive fantasy activity is associated with higher levels of sexual functioning, suggesting that sexual thoughts may reflect healthy sexuality (Nimbi et al., 2023a). Individuals with adequate sexual functioning tend to show more positive attitudes toward fantasies, perceive them as normal and important, and report a higher frequency of their occurrence (Nimbi et al., 2023a). In contrast, the role of negative emotions (e.g., guilt, worry, or embarrassment) related to fantasies remains less clear, with some studies reporting associations with lower sexual functioning in both men and women (e.g., Nimbi et al., 2023b), and others observing this association only in women (e.g., Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025). Consistent with these findings and our second hypothesis, the PSC were generally positively associated with sexual desire, sexual arousal, and penile erection/vaginal lubrication. However, the negative association observed between exploratory PSC and sexual functioning in men represents a noteworthy finding that merits further attention. As expected, and consistent with previous research (Moyano et al., 2016), NSC were negatively associated with sexual functioning and showed fewer and weaker significant associations. Overall, these results reinforce the importance of considering both positive and negative aspects of sexual cognition in research and clinical practice.

This study makes several relevant contributions. First, it confirms the suitability of the Spanish version of the SCC for assessing the multidimensionality of sexual cognitions. Additionally, it provides gender- and age-specific normative data for SCC-PSC scores, enabling, for the first time, the interpretation of raw scores within the Spanish population and enhancing the instrument’s clinical utility. Furthermore, the use of diverse recruitment strategies—including digital platforms, social media, organizations with varying profiles, and public spaces—ensured a broad and heterogeneous sample of adults from across Spain. The SCC’s ability to differentiate between different types of sexual cognitions assessing their frequency may be valuable in clinical settings, especially considering that, in the present study, these measures were associated with desire, arousal, and lubrication/erection in both solitary and partnered contexts, consistent with prior findings relating sexual fantasies to better sexual functioning (e. g., Shekarchi & Nimbi, 2025). Its clinical relevance is further underscored by the fact that the absence or marked reduction of sexual thoughts constitutes a diagnostic criterion for several sexual dysfunctions (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Moreover, given that sexual fantasies are often employed as a therapeutic resource (e.g., Newbury et al., 2012; Trudel et al., 2001), a psychometrically sound tool like the SCC can facilitate early and tailored interventions. This aligns with contemporary understandings of sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being concerning sexuality (World Health Organization, 2006) and underscores the importance of research not only in preventing sexual difficulties but also in promoting sexual and mental health. Notably, the definitions of sexual health (see World Health Organization, 2006) and mental health (see World Health Organization, 2022) share the term “state of well-being”.

However, some limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, a non-probability sampling method with age quotas was used, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Since the survey was conducted online and disseminated openly, it was not possible to determine the response rate or the specific setting in which participants completed the questionnaire (e.g., at home or in public spaces). This method may limit representativeness and generalizability, as certain groups—such as older adults, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, or those less familiar with digital tools—may be underrepresented due to limited internet access. This approach also involves self-selection, whereby participation is entirely voluntary and uncontrolled by the researcher. This sampling approach may lead to selection bias (Bethlehem, 2010), potentially overrepresenting individuals with specific interests or characteristics. Unfortunately, we did not collect data on variables such as ethnicity or socio-economic status, which could also compromise representativeness and generalizability. Nevertheless, the use of diversified recruitment strategies may have partially mitigated these limitations. However, no specific control was conducted over the channels or methods through which each entity disseminated the survey, which we acknowledge as inherent methodological limitation. Although online surveys may yield random or low-quality responses (Huang et al., 2012), the dataset was carefully reviewed to minimize this risk. Additionally, the composition of the sample could also be a limitation, as the study focused exclusively on cisgender heterosexual individuals. Further research is needed to examine the measurement invariance and applicability of these findings in populations with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, as recent studies suggest that the frequency and content of sexual thoughts may vary according to these variables (Nimbi et al., 2023a; Nimbi et al., 2020a, 2020b). Moreover, individuals with clinically diagnosed sexual dysfunctions were not included, which highlights the need to explore the SCC performance in clinical populations. Although partial strict invariance by gender was achieved for both the SCC-PSC and SCC-NSC, some items were freed and excluded from comparisons between men and women, thereby limiting the conceptual richness of the instrument. Additionally, total scores should be adjusted prior to use to ensure full measurement equivalence across genders. These limitations suggest that future research should aim to include more diverse samples and examine the psychometric properties of the SCC across variables such as sexual orientation and clinical diagnoses, to confirm its applicability and utility across a broader range of populations and contexts.

ConclusionsThe present study focuses on the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Sexual Cognition Checklist (SCC), providing adequate support for the reliability of its scores and sources of validity evidence for their interpretation. The SCC demonstrated measurement invariance across gender, age (only for SCC-PSC), educational level, current relationship status, and relationship length. Its scores were associated with sexual function, thereby contributing to a better understanding of this construct. Thus, the SCC can be considered the instrument of choice for assessing both positive and negative sexual cognitions in the Spanish population. Overall, and despite the limitations, these findings establish the SCC as a valuable tool for both research and clinical applications within the Spanish context.

FundingThis study has been funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF/EU, through the Research Project PID2022–136242OB-I00, and by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ESF+ through the grant PREP2022–001030 for University Professor Training of the first author. Additionally, this activity is part of the grant CEX2023–001312-M, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. This work is part of the first author’s thesis (Psychological Doctoral Programme B13 56 1; RD 99/2011).

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.