Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault (DFSA) survivors represent an under-researched clinical population that may constitute a distinct psychopathological profile among sexual assault survivors, as their experiences are often accompanied by confusion, memory impairment, and a lack of narrative coherence. This is the first study to investigate emotion-related attentional mechanisms in DFSA survivors using eye-tracking technology, as a window into broader cognitive processing. A clinical sample of 39 women who had experienced a recent, isolated sexual assault (19 DFSA, 20 non-DFSA) and 35 demographically matched non-exposed controls completed a free-viewing task while their eye movements were recorded. Participants viewed emotional images (threatening, happy, and neutral) paired with control neutral scenes. DFSA survivors showed a clear attentional bias toward threatening images during later attentional stages (engagement and sustained attention), while non-DFSA survivors did not exhibit significant modulation based on emotional content. Controls displayed typical emotion-driven attention, with sustained focus on happy stimuli. PTSD symptom clusters also influenced attentional patterns: greater avoidance was associated with reduced fixation time to emotional scenes, and dissociative symptoms with increased fixation time to neutral ones. These symptoms were more prevalent in the non-DFSA group. These findings suggest that attentional responses to emotional information vary according to assault typology and are shaped by specific PTSD symptom profiles. Clinically, this highlights the need for trauma interventions tailored to individual patterns of attention and emotional engagement. In particular, DFSA survivors may benefit from strategies that address threat sensitivity, while non-DFSA survivors may require approaches that promote emotional reconnection and reduce avoidance.

Sexual assault (SA) is a severe form of interpersonal trauma involving unwanted sexual contact through force, incapacitation, or coercion. Globally, between 0.3 % and 12 % of women have reported experiencing such assaults (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). SA is strongly associated with a range of posttraumatic stress symptoms (Campbell et al., 2009; Dworkin et al., 2017). However, the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that sustain this distress remain insufficiently understood. Recent research highlights attentional biases toward emotional information as a key process underlying trauma-related symptoms (Latack et al., 2017), due to the role of attention in emotion regulation and its link with psychological outcomes (Klanecky Earl et al., 2020). However, given the heterogeneity of SA experiences, it is crucial to consider the role of both individual and contextual factors in determining psychological consequences. One such factor is drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA), where the survivor is incapacitated by substances during the assault. DFSA has been associated with impaired trauma memories, in addition to a lack of a coherent trauma narrative, profound disruption of perceptual awareness, a perceived loss of control over one’s body, and persistent uncertainty regarding what occurred during the event, which may hinder the encoding and integration of the experience (Fields et al., 2022; Gauntlett-Gilbert et al., 2004; Saint-Martin et al., 2006). Subsequently, this may also affect the post-assault information processing and potentially shape psychological distress. Building on these considerations, the present study aims to explore whether attentional biases toward emotional stimuli differ between DFSA and non-DFSA survivors, to better understand how the specific characteristics of DFSA may modulate attentional processing and contribute to distinct psychological profiles.

Attentional bias to emotional information refers to the preferential allocation of attentional resources toward emotionally salient stimuli compared to neutral ones (Cisler & Koster, 2010). The emotional Stroop task is widely used to assess this bias, as it reveals cognitive interference through slower color naming of emotionally salient words compared to neutral ones (Williams et al., 1996). Research using this task with SA survivors has examined community samples of adults who experienced SA in childhood (Bremner et al., 2004; McNally et al., 2000), adulthood (Cassiday et al., 1992; Fleurkens et al., 2011; Foa et al., 1991), individuals with histories of revictimization (Field et al., 2001; Patriquin et al., 2012), and samples not distinguishing between childhood and adult abuse (Martinson et al., 2013). These studies typically compare survivors with and without post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), yielding mixed findings. While some report greater interference for trauma-related words in survivors with PTSD (Cassiday et al., 1992; Foa et al., 1991), others found no differences (Bremner et al., 2004; Martinson et al., 2013). Similarly, when comparing SA survivors without PTSD to healthy controls, results vary: whereas Cassiday et al. (1992) observed greater interference in survivors, others reported no group differences (Foa et al., 1991; Martinson et al., 2013; Patriquin et al., 2012). To integrate these inconsistencies, Latack et al. (2017) conducted a meta-analysis showing that SA survivors overall exhibit a significant attentional bias toward trauma-related stimuli, particularly those with PTSD, highlighting the role of PTSD symptoms in attentional processing. To further clarify this mechanism, McNally et al. (2000) examined the moderating role of trauma memory in adult survivors of childhood SA, comparing those with repressed, recovered, or continuous memories of the assault to non-victimized controls. Although greater interference was observed in those with recovered and continuous memories, relevant PTSD symptoms emerged as the strongest predictor of attentional bias. These findings underscore the relevance of PTSD but leave open questions about survivors who lack clear trauma memory, particularly relevant in DFSA cases. Investigating this subgroup within a clinical sample may be especially valuable, as these samples often include individuals with greater functional impairment, offering a more sensitive context for detecting attentional disruptions associated with trauma-related psychological difficulties.

Despite valuable insights, the widespread use of the emotional Stroop task presents methodological limitations. This paradigm primarily captures generalized cognitive interference, without isolating specific attentional processes such as initial orienting or disengagement from emotional content. Therefore, it remains unclear whether delays reflect genuine attentional biases or broader cognitive or emotional load related to trauma. To address these limitations, researchers have turned to tasks with greater temporal and spatial precision, such as the dot-probe paradigm and eye-tracking methods. The dot-probe task attempts to isolate attentional orienting by briefly presenting stimulus pairs—typically one threat-related and one neutral—followed by a probe in the location of one stimulus. Faster responses to probes replacing threat stimuli indicate attentional prioritization (MacLeod et al., 1986). Hirai et al. (2022) used this paradigm with threat-related and neutral words, comparing three community-based groups: i) women with a history of childhood SA (with or without adult revictimization); ii) women with adulthood SA; and iii) non-exposed controls. SA groups showed greater attentional bias toward threat-related words compared to controls, but no significant differences appeared between survivor subgroups. Although participants with other traumas were excluded from the study, grouping childhood and revictimized cases may have obscured the effects of trauma timing and accumulation. Furthermore, reliance on retrospective reports limits applicability to recent assault survivors. Examining individuals with a single, recent adulthood SA could clarify attentional biases more directly attributable to the assault.

Nevertheless, even in targeted samples, the dot-probe task, like the Stroop task, indirectly infers attention through reaction times, which are influenced by additional cognitive and motor processes, thereby limiting insight into how attention unfolds over time (Kimble et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2013). This is particularly problematic in trauma-exposed populations, where attentional patterns may shift rapidly or occur outside conscious awareness (Lazarov et al., 2019). To address these limitations, recent studies have turned to eye-tracking, a method that directly and continuously measures visual attention, allowing for a more detailed analysis of engagement with trauma-related stimuli. Eye movements closely reflect attentional shifts during visual tasks, where relevant complex stimuli compete for cognitive resources (e.g., social-emotional images) (Lazarov et al., 2019). By tracking gaze patterns over time, eye-tracking captures early attentional processes, such as initial orienting, and later attentional processes, such as engagement or sustained attention (Armstrong et al., 2013; Lazarov et al., 2019). Although no studies have used this method with SA survivors, related research in interpersonal violence offers useful insights. For instance, Lee and Lee (2012) studied women with histories of intimate partner violence (including psychological, physical, and sexual abuse) with and without PTSD, and a non-victimized control group. They presented a free-viewing paradigm with four emotional social scenes (threatening, happy, sad, and neutral) for 10 s. While no differences appeared in initial orienting, they found that survivors with PTSD showed more sustained attention on threatening images compared to both survivors without PTSD and non-exposed controls. Additionally, all survivors, regardless of the PTSD, displayed an attentional bias toward sad stimuli and reduced attention to happy scenes relative to the control group. To enhance experimental control when examining initial attentional orienting, Lee and Lee (2014) conducted a later study with the same trauma-survivor groups, administering an alternative task in which pairs of facial expressions were presented for 10 s (angry, fearful, or happy vs. neutral; and angry or fearful vs. happy). Researchers found no group differences in initial attention, although survivors with high PTSD showed longer sustained attention towards angry faces (vs. neutral) than low PTSD survivors, who in turn showed longer sustained attention than controls. For fearful faces, both survivor groups showed longer sustained attention than controls, with no significant differences between them. These findings point to a gradient of sustained attention as a function of PTSD symptom severity, especially in response to anger-related cues; however, the results can not be generalized to SA survivors, as samples are not comparable. Additionally, given PTSD’s dimensional nature and the varied cognitive impact of its symptom clusters, future research should explore how specific symptom dimensions relate to attentional biases for a more nuanced understanding of trauma processing.

This study aims to address key gaps in the literature by comparing attentional biases in a clinical sample of individuals with DFSA and those without DFSA. To isolate the effects of trauma type, participants were selected based on the experience of a single SA episode within the past year, with no prior SA, other traumatic experiences, or pre-existing mental health conditions. A demographically matched control group was also recruited. To examine early attentional orienting, engagement, and sustained attention, we employed a free-viewing eye-tracking paradigm, using emotionally relevant images (threatening, happy, neutral) paired with control non-social stimuli, avoiding the use of sexually explicit stimuli that may be processed differently for DFSA survivors, who often lack detailed recollections. Additionally, PTSD symptom severity was explored to examine its potential associations with attentional biases. Based on previous findings, we propose three hypotheses: (i) drawing on research on attentional bias and memory impairment, we hypothesize that DFSA survivors will show fewer attentional bias toward threatening stimuli compared to non-DFSA survivors, likely resembling controls more closely (McNally et al., 2000); (ii) following Lee and Lee (2014) with a similar task and a sample of interpersonal trauma survivors, we expect no group differences during early attention stages neither with the control group; however, we anticipate that SA survivors overall will show increased sustained attention and engagement to threatening stimuli (Cassiday et al., 1992; Fleurkens et al., 2011; Foa et al., 1991; Martinson et al., 2013); and (iii) to extend prior PTSD research (see Lazarov et al., 2019 for a systematic review in PTSD samples), we hypothesize that specific PTSD symptom severity would associate particular attentional bias to threat in SA survivors.

MethodsParticipantsCase files from 400 users of a foundation assisting SA survivors were reviewed. From these, 133 cases were selected based on the criterion that the assault had occurred within the past year, ensuring recency of trauma exposure. A priori sample size was calculated using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) for a repeated-measures ANOVA with one between-subjects factor (three groups) and one within-subjects factor (four valences). The calculation was based on a medium effect size (f = 0.25), an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.80, and a conservative correlation among repeated measures of 0.5. The minimum required sample size was estimated at 66 participants. Our final sample of 74 women exceeded this threshold. After applying exclusion criteria—including being under 18 years old, having a history of childhood SA or previous SA, other traumatic experiences (e.g., disasters, kidnapping, family homicide), or prior psychiatric diagnosis—a total of 39 women were included. These participants were divided into two clinical groups: (1) A group of non-DFSA survivors, that is, survivors of SA involving physical force or coercion, but no DF (n = 20), and (2) survivors of DFSA (n = 19). An age-, gender-, education-, and nationality-matched control group (n = 35) was recruited through community advertisements, applying the same exclusion criteria and additionally requiring no history of SA. An ethics committee approved the study on May 19, 2020 (Ethics Code: 2020–065–1), and all participants provided informed consent. See Fig. 1 for the sample recruitment flowchart. Sociodemographic data are described in Table 1.

Sociodemographic data of non-DFSA survivors, DFSA survivors, and the Control group.

Note. Data are presented as means, with standard deviations shown in parentheses.

All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. PTSD symptoms were assessed using the PTSD Scale Clinician-Administered for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., 2018), which evaluates 20 items on a 0–4 severity scale, yielding a total score (0–80) and scores for each DSM-5 symptom cluster: re-experiencing (B), avoidance (C), negative cognitions and mood (D), hyperarousal (E), and dissociation. The CAPS-5 has demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.88) and test-retest reliability (κ = 0.83) (Weathers et al., 2018).

StimuliThe stimuli included 128 scenes selected from the International Affective Picture System (Lang et al., 2005). The stimuli were the same as those used in Nummenmaa et al. (2006) and varied only in emotional valence and arousal, while being matched for visual properties such as complexity and luminance. For each emotional category, 16 images were selected, corresponding to happy, threatening, and neutral social scenes. Happy scenes depicted individuals with positive affect, threatening scenes showed either hostile individuals or people in threatening situations, and neutral scenes portrayed individuals engaged in everyday activities. Additionally, 80 non-social control images of inanimate objects were included. Because our study employed the validated stimulus set and task parameters from Nummenmaa et al. (2006), no additional affective ratings were collected from the present sample, which also helped to avoid potential practice or carry-over effects. According to the original validation, happy images were rated more positively than both threatening and control images, and neutral and control images were rated more positively than threatening ones, with no significant difference between neutral and control images. In terms of arousal, happy and threatening images elicited higher arousal ratings than neutral and control images, though no differences were found between happy and threatening stimuli, or between neutral and control stimuli. Participants viewed 64 trials (48 experimental, 16 filler), each composed of two randomly paired images. These included 16 trials each for happy-control, threatening-control, and neutral-control pairs, along with 16 filler trials of neutral-control pairs. Each trial began with a central fixation cross, which disappeared after a steady gaze. Image pairs appeared for 3 s in diagonally opposite screen corners, with image positions counterbalanced across trials. Randomization of presentation order and image placement ensured that participants could not rely on a fixed visual scanning strategy. See Fig. 2 for an illustration of how a trial was presented.

ApparatusEye movements were recorded using a portable Tobii Pro Fusion Eye Tracker with a 250 Hz sampling rate; no chin-rest was used since the apparatus allowed head movement with a high-precision gaze tracking. Visual stimuli were displayed on a 23.8″ ASUS VA249HE Full HD (1920 × 1080) LED monitor with a 60 Hz refresh rate, positioned at a viewing distance of 60 cm.

ProcedureParticipants completed demographic questionnaires and the CAPS-5 before the eye-tracking session. They were seated in a height-adjustable chair in a dimly lit, sound-attenuated room. Before starting the task, a calibration procedure was performed using a nine-point moving target followed by a four-point validation, with an acceptable error threshold of <1.5° The calibration was repeated as many times as necessary until this criterion was met, ensuring high accuracy of gaze data. Consequently, no participants were excluded due to calibration failure or signal loss. Additionally, in accordance with standard eye-tracking quality protocols, a trial was excluded from analysis if fewer than 75 % of gaze samples (individual data points recorded at 250 Hz) were successfully captured or if no fixation was detected within any area of interest (AOI). To ensure robust data for analysis, participants were required to retain at least 75 % of trials in each condition (9 out of 12) and 75 % of trials overall (48 out of 64). All participants successfully met these inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the average gaze sample retention rate for the entire sample was high (86 %), indicating consistently reliable data collection across participants and conditions. Participants were instructed to free-view the images naturally, “as if looking at a photo album”. The experimenter monitored calibration and performance in real time.

Data analysisData were processed using a velocity-based algorithm, applying a minimum fixation duration threshold of 100 ms and a peak velocity threshold of 40°/s to identify fixation events. Areas of interest (AOIs) were defined as the full extent of each visual scene. To examine different stages of attentional processing, several eye-tracking measures were extracted. Early attentional processes, referred to as orienting, were assessed through the latency and direction of initial eye movements occurring immediately after stimulus onset. These were captured using two indices: (i) initial fixation latency, measuring the time (in ms) taken to first fixate on the target scene, and (ii) initial fixation probability, which was defined as the proportion of trials in which the very first fixation after stimulus onset landed on the AOI corresponding to the target emotional (happy, threatening, neutral) versus the paired control image. This metric reflects the initial attentional orienting toward a given stimulus category. Subsequent attentional engagement—operationalized here as the depth of attentional allocation during the first encounter with a stimulus—was indexed by (iii) first-pass duration (i.e., the sum of fixation durations made on the image during its initial viewing, before the gaze shifted away). Finally, sustained attention, or the prolonged allocation of attention over time, was assessed through two complementary indices: (iv) percentage of total duration, capturing the proportion of the entire viewing time (including re-fixations) spent on the target scene during the 3-second presentation window, and (v) percentage of total fixations, representing the proportion of the total number of fixations and re-fixations on the scene throughout the viewing period.

Eye movement data were analyzed using a 3 (Group: non-DFSA, DFSA, Control) × 3 (Valence: neutral, happy, threatening) mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Group as the between-subjects factor and Valence as the within-subjects factor. When a significant interaction between Group and Valence was observed, follow-up simple effects analyses were conducted. For comparisons involving the Valence factor, p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons. In addition, exploratory correlation analyses were conducted within the non-DFSA and DFSA groups to assess the associations between attentional outcomes and PTSD symptom severity, as measured by CAPS-5 scores. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 30.0.0).

ResultsDescriptive data of the measures are displayed in Table 2.

Eye-Tracking Measures for Neutral, Happy, and Threatening Stimuli Across Each Group.

Note. Data are presented as means, with standard deviations shown in parentheses.

The ANOVA of the latency of initial fixation only showed that the effect of Valence approached significance, F(2142) = 13,11, p < .001, η2 = 0.16, with significantly shorter latencies for happy and threatening images compared to neutral ones (all ps < 0.001). Neither the effect of Group nor the Valence x Group interaction was significant (all Fs < 1).

Probability of initial fixationNeither the Group, the Valence effect, nor the Valence x Group interaction was significant (all Fs < 1).

First-pass durationThe ANOVA on first-pass duration revealed a significant main effect of Valence, F(2, 142) = 16.62, p < .001, η2 = 0.19, which was further qualified by a significant Valence × Group interaction, F(4, 142) = 3.04, p = .019, η2 = 0.079. No significant main effect of Group was observed (p = .22).

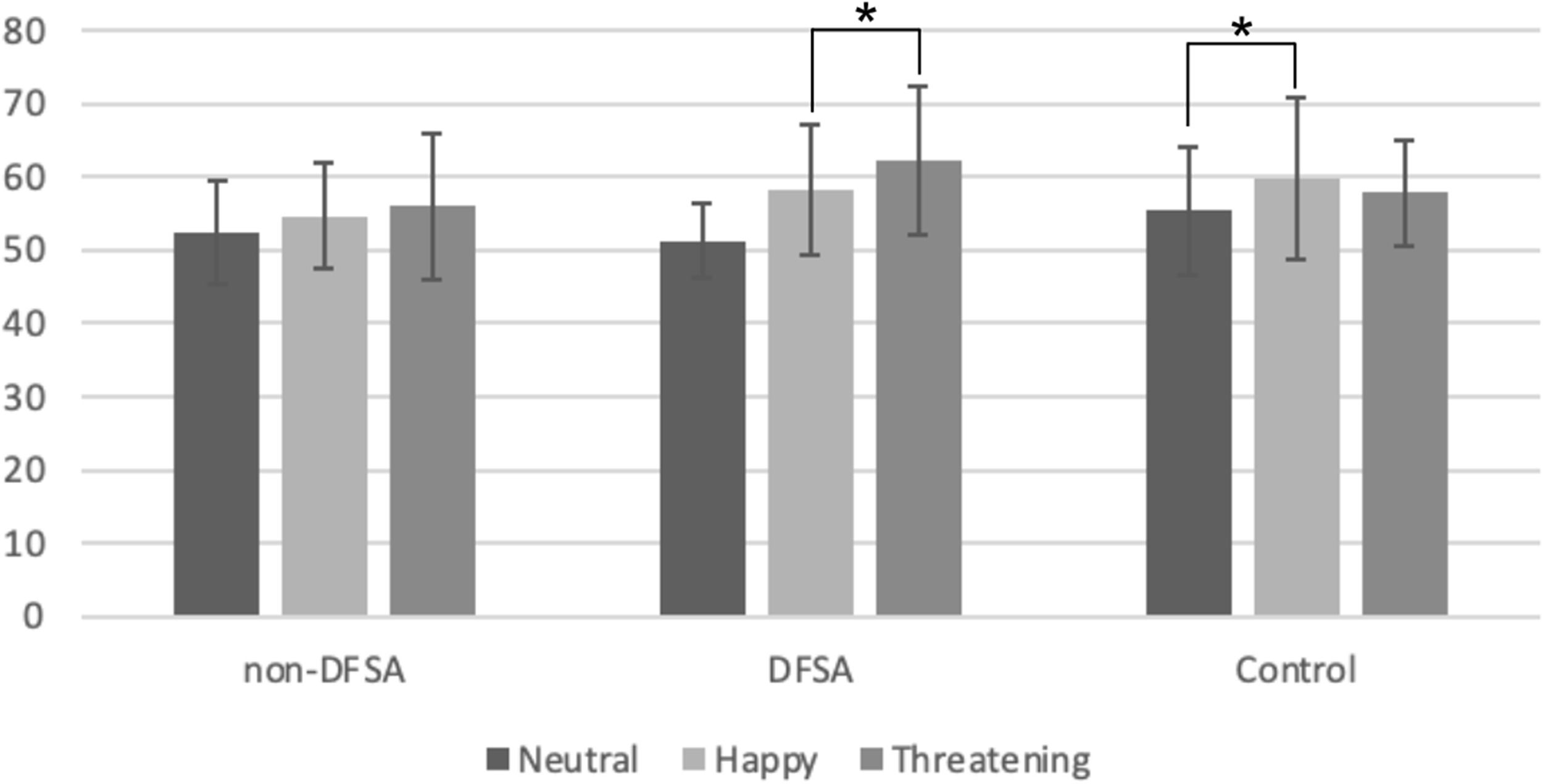

To further explore the Valence × Group interaction, simple effects analyses were conducted to examine the effect of Valence within each group. A significant Valence effect was found for the DFSA group, F(2, 36) = 13.40, p < .001, η2 = 0.427, and for the control group, F(2, 68) = 3.91, p = .025, η2 = 0.103, but not for the non-DFSA group (p = .14). In the DFSA group, first-pass duration was significantly longer for threatening images compared to happy (p < .001) and neutral images (p = .001), and for happy images compared to neutral ones (p = .003). In the control group, first-pass duration was significantly longer for threatening images and happy images compared to neutral ones (p = .007 and p < .001, respectively); no differences were found between threatening and happy images (p = .15). See Fig. 3.

Percentage of total durationThe ANOVA of the percentage of total duration revealed an effect of Valence, F(2, 142) = 12.97, p < .001, η2 = 0.154, which was qualified by a Valence x Group interaction, F(4, 142) = 2.73, p = .031, η2 = 0.071. No significant Group effect was found (p = .19).

To examine the Group x Valence interaction, we conducted simple effects tests of Valence for each Group. While a Valence effect was found for the DFSA group, F(2, 36) = 12.78, p < .001, η2 = 0.415, and the control group, F(2, 68) = 3.18, p = .048, η2 = 0.085, it was not found in the non-DFSA group (p = .22). In the DFSA group, the percentage of total duration was significantly longer for threatening images compared to happy (p < .001), no other differences were found (all ps > 0.58). In the control group, the percentage of total duration was significantly longer for happy images compared to neutral ones (p < .001,). No other differences were found (all ps > 0.27). See Fig. 4a.

Percentage of total fixationsThe ANOVA of the percentage of total duration revealed an effect of Valence, F(2, 142) = 14.62, p < .001, η2 = 0.171, which was qualified by a Valence x Group interaction, F(4, 142) = 4.14, p = .003, η2 = 0.104. No significant Group effect was found (p = .25).

To examine the Group x Valence interaction, we conducted simple effects tests of Valence for each Group. While a Valence effect was found for the DFSA group, F(2, 36) = 24.09, p < .001, η2 = 0.572, and the control group, F(2, 68) = 3.51, p = .035, η2 = 0.094, it not found in the non-DFSA group (p = .32). In the DFSA group, the percentage of total fixations was significantly longer for threatening images compared to happy (p < .001), and neutral images (p = .011), and for happy images compared to neutral ones (p = .018). In the control group, the percentage of total duration was significantly longer for happy images compared to neutral ones (p < .001). No other differences were found (all ps > 0.12). See Fig. 4b.

Correlational analysesExploratory analyses conducted within the non-DFSA and DFSA groups examined the relationship between attentional outcomes and the severity of PTSD symptoms. A greater severity of avoidance symptoms was associated with reduced first-pass duration toward both threatening (r2 = −0.328, p = .041) and happy images (r2 = −0.407, p = .010). In contrast, a greater severity of dissociative symptoms was associated with a higher percentage of total fixations on neutral images (r² = 0.326, p = .043). No other significant associations were observed (all ps > 0.06). See Table 3 for the full correlation matrix and the Supplementary Material for scatterplots with regression lines depicting the significant relationships.

Correlation matrix between attentional outcomes and the severity of PTSD symptoms within the non-DFSA and the DFSA groups.

Note. The data show the coefficient of determination (R²), with significance levels reported in parentheses. Positive correlations are indicated with an asterisk.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate attentional biases in DFSA and non-DFSA survivors using a free-viewing eye-tracking task, approximating natural visual exploration of socio-emotional (threatening, happy, and neutral) and non-social stimuli. The results provide converging evidence for emotion-dependent attentional modulation shaped by group differences. Specifically, DFSA survivors exhibited both engagement and sustained attentional biases toward threatening scenes, followed by happy scenes, with comparatively less attention to neutral ones. In contrast, the non-DFSA group showed no attentional bias based on emotional valence. For the control group, although threatening and happy scenes elicited greater attentional engagement than neutral ones, sustained attention was predominantly directed toward happy scenes. Hence, these group-specific patterns were not attributable to differences in initial orienting. Finally, exploratory correlational analyses revealed that greater avoidance symptom severity was associated with reduced first-pass duration on both threatening and happy stimuli, whereas higher dissociative symptomatology was linked to increased fixation frequency on neutral stimuli. These findings highlight the differential contribution of specific PTSD symptom dimensions to attentional processing and underscore the importance of considering SA typology in trauma research.

Contrary to initial hypotheses based on the inaccessibility of traumatic memory studies (McNally et al., 2000), our findings indicated that, unlike non-DFSA survivors, DFSA survivors exhibited an attentional bias toward threatening scenes compared to happy and neutral ones. This attentional pattern may reflect the broader clinical complexity characterizing DFSA experiences. These assaults, in addition to the amnesia regarding the event, often involve a lack of a coherent trauma narrative, profound disruption of perceptual awareness, a perceived loss of control over one’s body, and persistent uncertainty regarding what occurred during the event (see Saint-Martin et al., 2006 for a review). Such conditions may hinder the integration of the trauma and contribute to a sustained state of hypervigilance. Within this context, the attentional bias toward threatening stimuli may reflect a threat-monitoring mechanism, whereby ambiguous or socially charged cues (even if not explicitly sexual) gain emotional salience due to their resonance with the unresolved and disorienting features of the traumatic experience (Busardò et al., 2019). In contrast, while the control group displays the expected pattern of attentional engagement with emotional stimuli and sustained attention to positive content—indicative of intact emotional processing—the absence of emotion-dependent attentional modulation in the non-DFSA group may point to a disruption in these normative processes, potentially reflecting affective blunting or reduced emotional responsiveness following trauma. This pattern may indicate the operation of regulatory strategies aimed at dampening emotional arousal in the face of distressing stimuli, such as attentional distraction (Cisler & Koster, 2010). Alternatively, the lack of attentional bias in the non-DFSA group may be attributed to the limited sexual trauma relevance of the socio-emotional scenes used in the present study. That is, although the stimuli depicted scenes with threatening valence, they may not have been sufficiently specific or personally meaningful to evoke trauma-related processing in this group. In line with this, Pineles et al. (2009) found that SA survivors did not exhibit attentional biases when exposed to general threat-related stimuli, emphasizing the importance of stimulus relevance in eliciting trauma-linked attentional patterns. Consistent with this view, previous research employing a different methodology and stimuli that more directly reflect the content of sexual trauma, such as words or images with sexual threat connotations, has reported stronger attentional biases in similar samples (Cassiday et al., 1992; Fleurkens et al., 2011; Foa et al., 1991; Martinson et al., 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest that attentional biases in non-DFSA survivors may be more likely to emerge when the emotional content of the stimuli closely aligns with the specific nature of their traumatic experience.

Concerning the stages of attentional processing, the absence of group differences during the initial orienting suggests that early, automatic components of attention may not be significantly affected by trauma-related processes. One explanation for this lack of early attentional biases may lie like the stimuli: complex socio-emotional scenes, as opposed to isolated words or facial expressions, likely required participants to perform an initial rapid scan of the visual scene before selectively engaging with a specific image, thereby limiting the emergence of early attentional modulation (Lazarov et al., 2019). In contrast, differences became evident during later stages, specifically engagement and sustained attention, which rely more heavily on controlled and voluntary processes known to be disrupted by trauma-related difficulties in emotion regulation and attentional control (Gauntlett-Gilbert et al., 2004; Klanecky Earl et al., 2020). This pattern is consistent with findings from Lazarov et al. (2019) and Lee and Lee (2012, 2014), who reported that attentional biases in trauma-exposed individuals are more likely to emerge during sustained rather than initial attention. The sustained attention observed in the DFSA group may be driven by the uncertainty and fragmented recall associated with the assault (Thompson, 2021), which could increase rumination and perseverative thinking, making it harder to disengage from threat-related cues (Lazarov et al., 2019). Conversely, the absence of attentional modulation among non-DFSA survivors across stages may reflect a different psychological response, likely related to greater acknowledgment and lower uncertainty surrounding the event (Zinzow et al., 2010). These results suggest that controlled attentional patterns are shaped not only by trauma-related processes but also by the emotional valence of social scenes.

Finally, unlike previous research that assessed PTSD categorically (Lazarov et al., 2019; Lee & Lee, 2012, 2014), the present study underscores the value of examining the distinct contributions of specific PTSD symptom clusters to attentional processing. Prior studies have found an association between overall PTSD and attentional bias toward threat-related stimuli, although mostly focused on individuals whose trauma occurred during childhood or in the distant past. This may limit the detection of certain PTSD symptoms, such as avoidance or dissociation, that often emerge more prominently in the acute aftermath of trauma and may exert differential effects on attentional patterns. Our findings reveal that individuals with recent SA and elevated avoidance tendencies tend to engage less with emotionally salient information, while higher levels of dissociative symptoms were associated with increased attention to neutral stimuli. Notably, these PTSD symptoms were more salient among non-DFSA participants than in DFSA ones, which may explain the differences in attentional biases observed between the two groups. According to the Emotional Processing Theory, avoidance of internal and external trauma-related cues is understood as a strategy to reduce emotional distress (Foa et al., 2007). In parallel, the association between dissociative symptoms and the increased number of fixations on neutral stimuli is consistent with the theoretical conceptualization of dissociative symptoms as altered states of consciousness characterized by disruptions in perceptual integration and reduced awareness of the external environment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Additionally, these findings extend previous research indicating that dissociative symptoms diminish responsiveness to emotionally charged cues (Herzog et al., 2019). Hence, the attentional shift away from emotionally charged toward neutral content may reflect both a specific psychological profile and a protective strategy common to non-DFSA survivors, allowing them to reduce the exposure to affectively overwhelming stimuli (Herzog et al., 2019; Lanius et al., 2010).

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size—stemming from the strict exclusion criteria and the focus on a female-only sample—may limit the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the modest sample size constrained our ability to conduct formal moderation analyses (e.g., group × PTSD interactions). Future studies with larger and more diverse samples should address these limitations and directly test such moderation effects. However, studies using similar populations and methodologies typically rely on small sample sizes and predominantly female participants (Lazarov et al., 2019; Lee & Lee, 2014), likely reflecting the fact that sexual violence is a social issue that disproportionately affects women (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). Nevertheless, by excluding individuals with histories of childhood or prior adult SA, together with other traumatic experiences and mental health conditions, the study was able to isolate the effects of a recent SA, particularly in cases involving DFSA, without the confounding influence of trauma chronicity or cumulative exposure. This methodological decision enhances the internal validity and enlarges the knowledge about this under-researched population. Another potential limitation concerns the nature of the visual stimuli. While the use of non-sexual emotional images was intentional to avoid participant discomfort and the risk of trauma-specific reactivity, these stimuli may not evoke the same trauma-related reactions as content more closely tied to the context of the assault. Nonetheless, it is important to note that one of the objectives of the present study was to examine attentional bias among DFSA survivors (i.e., with high uncertainty and lack of a clear narrative about their traumatic event); therefore, specific trauma-related stimuli may not be meaningfully connected to the individual's subjective experience. In this context, the use of more general emotional stimuli allowed for a controlled assessment of threat sensitivity without triggering trauma-specific reactivity that may not be uniformly processed across participants. Additionally, this design also enhances ecological validity by reflecting real-world attentional demands, where individuals must process and prioritize complex, socially relevant information in dynamic environments. Lastly, although this study may suggest that attentional differences in the DFSA group may be attributed to the absence of clear memories of the assault, we conducted an additional analysis including participants’ memory clarity as an independent variable. This variable did not yield significant effects in any of the eye-tracking outcomes (all Fs < 1), suggesting that memory clarity alone does not account for the observed attentional patterns.

Despite its limitations, the present study presents several methodological strengths. While many previous investigations have yielded valuable insights using community samples and traditional attentional tasks such as the Stroop or dot-probe paradigms (Foa et al., 1991; Martinson et al., 2013; Cassiday et al., 1992; Fleurkens et al., 2011; McNally et al., 2000; Hirai et al., 2022), the present study contributes to the existing knowledge by employing both a highly specific clinical sample and eye-tracking methodology. This combination enhances the clinical relevance of the findings and allows for a temporally fine-grained examination of attentional processing across its different phases (i.e., initial orienting, engagement, and sustained attention), offering a more nuanced understanding of trauma-related cognitive underlying mechanisms. Finally, assessing PTSD symptoms dimensionally, rather than categorically or divided into higher or lower levels (Lee & Lee, 2014), enabled a more detailed examination of how specific symptom clusters relate to attentional biases, offering insights that may be obscured in dichotomous diagnostic approaches.

In conclusion, our findings reveal a clear dissociation in attentional patterns based on assault typology: DFSA survivors exhibited an attentional engagement and sustained attentional bias toward threatening stimuli, whereas no attentional biases were observed in the non-DFSA group. This suggests that specific clinical features associated with DFSA, such as uncertainty, confusion, and the lack of a coherent narrative of the assault, may play a crucial role in shaping hypervigilant attentional responses to threat. Notably, although early stages of attentional processing appeared unaffected across groups, differences emerged during later, controlled stages of attentional processing (engagement and maintenance). Additionally, our dimensional approach to PTSD symptoms revealed that specific clusters account for variability in attentional patterns. Critically, the non-DFSA group exhibited greater avoidance and dissociation symptoms than the DFSA one, which may explain the absence of attentional bias in the non-DFSA group. Future research should further investigate how these symptom dimensions interact with different trauma contexts and whether attentional processing may serve as a cognitive marker of divergent trajectories of trauma adaptation.

These findings carry significant clinical implications for tailoring the assessment and treatment of sexual assault survivors. For DFSA survivors, interventions should incorporate strategies to modulate hypervigilance and difficulty disengaging from threat, such as attentional retraining or grounding techniques, to reduce over-engagement. In contrast, for non-DFSA survivors, the absence of emotional modulation and higher avoidance/dissociation highlight the need for approaches that foster emotional reconnection and integration of avoided affect, such as carefully paced exposure-based therapies. Beyond assault typology, our results underscore the value of tailoring interventions to the individual's PTSD symptom profile, as specific clusters exert distinct effects on attention (Klanecky Earl et al., 2020). Integrating attentional assessment into clinical evaluation could thus enhance case formulation by identifying and maintaining cognitive-emotional patterns. Ultimately, recognizing this heterogeneity is key to developing more personalized and effective trauma care pathways.

Author noteThe publication of the study has been funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI21/00,549 and co-funded by the European Union.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Health Research Institute La Fe (Ethics Code: 2020–065–1) on May 19, 2020. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to assist with grammar revision and language refinement. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FoundingThis work was supported by the Carlos III Health Institute under grants CM24/00123, CM22/00097, PI18/01352, PI21/00549, PI24/01259, and CP21/00085; the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through grants FPU18/01997 and FPU20/02548; the NextGenerationEU through the grant MS21‐063; and the Generalitat Valenciana through CIAICO/2022/233.

The publication of the study has been funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI21/00549 and co-funded by the European Union.

Data statementThe datasets generated and analyzed during the current study contain sensitive information related to sexual assault survivors and cannot be made publicly available to protect participant confidentiality. De-identified data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to ethical approval and safeguarding of participants’ privacy.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.