Edited by: Dr. Sergi Bermúdez i Badia

(University of Madeira, Funchal, , Portugal)

Dr. Alice Chirico

(No Organisation - Home based - 0595549)

Dr. Andrea Gaggioli

(Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milano,Italy)

Prof. Dr. Ana Lúcia Faria

(University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal)

Last update: December 2025

More infoInsomnia is a prevalent condition with substantial health, economic, and societal burden. Despite evidence supporting the use of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) accessibility remains limited, shows high dropout rates, and is ineffective for 30 % of patients. Virtual reality (VR) mindfulness offers a novel, engaging, and scalable alternative, with the potential for enhanced treatment adherence compared to other digital health interventions (e.g., apps, audio, and online programs). VR has demonstrated efficacy in treating conditions such as chronic pain, anxiety, and depression, disorders often co-occurring with insomnia, its potential for treating insomnia remains underexplored.

AimsThis study aimed to (1) assess the acceptability of VR mindfulness for the treatment of insomnia from clinicians and patients with chronic insomnia, and (2) identify barriers and facilitators to its adoption and clinical implementation.

MethodsA mixed-methods design was used, including a questionnaire assessing familiarity with digital health technologies (DHTs) and the perceived utility of VR mindfulness for insomnia, followed by a 2-h in-person focus group. Participants explored and evaluated four VR mindfulness applications. The convenience sample included (1) community-dwelling adults with chronic insomnia (ISI > 10, PSQI > 10) and (2) clinicians registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) familiar with insomnia treatment. Focus group data were analysed using thematic analysis and inductive reasoning

Results19 patients (14 F, 4 M; mean age 46.26 ± 9.19 years) with moderate-to-severe chronic insomnia (mean ISI 17.48 ± 4.29; mean PSQI 14.46 ± 4.22) and 14 clinicians (9 F, 5 M; mean age 43.93 ± 12.01 years) with an average of 15 ± 12.28 years of experience participated. 72.8 % expressed curiosity and 36.4 % excitement at the prospect of trying VR mindfulness; 36.8 % of patients and 57.1 % of clinicians stated prior experience with VR; all welcomed the possibility of a new treatment for insomnia; VR mindfulness was described as “high-tech, futuristic, expensive”, and “complicated to use”. Post-interaction patients and clinicians were enthusiastic about VR mindfulness, describing it described it as “easy to use” and “more engaging” than other approaches to mindfulness. 89.5% of patients became confident of the potential for VR mindfulness to be an effective treatment for insomnia; expressing willingness to use and recommend. Clinicians recognised its clinical utility and scalability after the brief exposure, describing it as an “on-ramp" to traditional mindfulness; and anticipated strong patient interest. 98 % (n = 13) stated that contingent on its feasibility, incorporating VR mindfulness into clinical practice would immediately improve patient care. Cost was not a barrier to patient adoption; comfort and efficacy were. The safety and commercial availability of VR mindfulness were key facilitators to adoption.

ConclusionVR mindfulness is an acceptable, engaging, and scalable treatment for insomnia, with potential for rapid clinical adoption. Further research demonstrating its feasibility and efficacy are important first steps to integration into clinical practice.

Insomnia Disorder (ID) is characterized by persistent and chronic sleep disturbances that result in significant daytime distress or functional impairments. Global estimates of chronic insomnia vary widely, from 10 % to a high of 60 % (C. M. Morin & Jarrin, 2022). Despite its widespread prevalence, ID remains under-reported and under-diagnosed in clinical settings, with a disproportionate impact on women and older adults. ID significantly elevates the risk of developing cardiometabolic conditions (Zheng et al., 2019), including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (Johnson et al., 2021). Longitudinal studies have also demonstrated a 50 % increased risk of Alzheimer's disease in individuals with chronic insomnia (Lv et al., 2022; Wong & Lovier, 2023; Xiong et al., 2024). Patients with ID often experience poorer overall health, diminished quality of life, and impaired social functioning (Sivertsen et al., 2014). Furthermore, workplace productivity is significantly compromised, with ID contributing to both high rates of absenteeism and presenteeism, as well as decreased concentration and performance (Espie et al., 2018).

ID is the third most prevalent mental disorder, and extensive research, including genome-wide association studies and experimental investigations, has established ID as a key transdiagnostic risk factor for the development of common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression (Van Someren, 2021). ID is now recognized as an early marker of depression onset, sharing common pathophysiological mechanisms with mood disorders (Hein et al., 2017). The relationship between insomnia and mental disorders is bidirectional, and effective treatment of insomnia has the potential to reduce mental disorders such as depression (Irwin et al., 2022).

Treatment optionsCurrent clinical management of ID remains limited, with a predominant reliance on sedative/hypnotic (Miller et al., 2017) medications, which offer only short-term benefits and are associated with substantial side effects (Riemann et al., 2023). Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is regarded as the gold standard in treatment; however, it remains ineffective for approximately 30 % of patients (Riemann & Perlis, 2009), exhibits high dropout rates (Ong et al., 2008), and tends to result in relapse, particularly within the first year following treatment (Morin et al., 2009). Access to specialist referral is limited and typically incurs significant out-of-pocket costs (Buenaver et al., 2019). The development of apps and online training to increase access to CBTi has improved accessibility, but adherence rates are low.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have shown promise as effective treatments for insomnia. MBIs show significant improvement to subjective measures of sleep quality, insomnia severity, and sleep efficiency (Gong et al., 2016; Ong et al., 2014). Evidence from polysomnography studies is less conclusive (Kanen et al., n.d.). The mechanism of action is unclear but believed to include a reduction in pre-sleep cognitive arousal and stress, known contributors to insomnia (Ong & Smith, 2017). Mindfulness practices encourage individuals to cultivate a non-judgmental awareness of their thoughts and feelings, which can reduce hyperarousal, anxiety, and rumination – key contributors to insomnia maintenance (Morin et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2008), Approaches such as mindfulness, which emphasize self-awareness and acceptance rather than cognitive restructuring are both more acceptable and preferred by individuals with insomnia (Buenaver et al., 2019), and show similar treatment retention (Goldberg et al., 2022).

Given that individuals with insomnia frequently experience hyperarousal and heightened distractibility, the immersive nature of VR may be particularly beneficial by blocking environmental stimuli that typically interfere with mindfulness practice, thereby facilitating the focused attention necessary for therapeutic benefit

VR mindfulnessVirtual reality (VR) is a rapidly evolving technology that creates an immersive and interactive computer-generated environment, using head-mounted displays and motion-tracking devices. By engaging multiple sensory modalities, VR evokes a heightened sense of presence that enables users to ‘suspend’ their current reality serving as a gateway to ‘being in’ the virtual one. VR has been used to effectively support the delivery of psychological interventions in the treatment of chronic pain, anxiety, depression, and PTSD, since the early 1990s (Freeman et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019). VR mindfulness offers an affordable, accessible, and scalable treatment delivery option, especially for those who struggle with traditional mindfulness practices. However, little is known about the clinical potential of VR mindfulness. To address this limitation, this study proposes to (i) assess the acceptability of VR mindfulness as a treatment for insomnia in a community sample with chronic insomnia and clinicians familiar with its treatment before and after interacting with the technology, and (ii) elucidate barriers to its adoption and approaches to successful integration into clinical practice.

MethodsStudy designWe used a sequential mixed methods design with two distinct stages. Stage one involved quantitative data collection including eligibility screening, demographics, socioeconomic factors, digital health technology familiarity, and baseline perceptions of VR mindfulness for insomnia treatment. Stage two comprised 2-h focus groups to evaluate the acceptability, usability, and feasibility of VR-delivered mindfulness as a potential treatment for chronic insomnia, incorporating structured hands-on exploration of four commercially available VR mindfulness applications. By capturing participant perspectives both before the focus group and immediately after the hands-on exploration, we measured changes in perceived acceptability and utility of VR mindfulness in the context of increased familiarity. This approach allowed participants to provide authentic, experience-based insights rather than hypothetical opinions, with quantitative measures supporting interpretation of qualitative themes.

Research activities were reviewed and approved by The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2023–0216). All participants provided written informed consent and received a $100 gift card to compensate for travel costs.

Rationale for focus group methodologyFocus group methodology (Kitzinger, 1995) was chosen due to its established strength in eliciting socially constructed, context-specific perspectives—particularly valuable when investigating novel interventions where empirical frameworks remain underdeveloped, as is the case with VR-delivered mindfulness for insomnia. Focus groups served as a formative, exploratory method to elicit distinct stakeholder insights on acceptability and potential clinical utility. Separate sessions were conducted for patients and clinicians to minimize power dynamics, facilitate open dialogue, and ensure participants felt comfortable expressing their views, reflecting best practice in implementation and digital health research (Morgan, 1996).

Theoretical framework: technology acceptance modelThe Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) provided the conceptual framework for examining perceived acceptability and utility both before and immediately after hands-on VR experience. TAM proposes that perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) are primary determinants of users' intention to adopt new technologies. These core constructs guided both the structure of focus group questions and interpretation of participant responses. PU mapped onto appraisals of therapeutic relevance, including potential to support mindfulness, focus, and sleep improvement. PEOU captured usability aspects such as navigation clarity, instruction comprehensibility, and headset comfort. Discussion of these theoretical predictors was followed by exploration of behavioral intention regarding future use, alongside general attitudes toward VR mindfulness for insomnia treatment. This structured approach enabled identification of both individual- and system-level facilitators and barriers to adoption.

Distinct stakeholder groups (patients vs. clinicians)Patients and clinicians were recruited to provide distinct perspectives—clinicians as providers of care, patients as recipients with a personal, lived experience perspective. The inclusion of both patients and clinicians reflects a person-centred, translational approach to digital health evaluation. This approach is consistent with implementation frameworks that emphasise the importance of multi-stakeholder input (Greenhalgh et al., 2017). Patients provided essential insights into the acceptability, usability, and relevance of VR mindfulness, informing factors directly related to engagement and adherence. Clinicians provided complementary perspectives on appropriateness for diverse clinical populations, integration within existing care pathways, and system-level feasibility (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2013). This dual perspective strengthens the ecological validity and translational utility of findings (Kushniruk & Nohr, 2016) consistent with digital health development guidelines that recommend early engagement of implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009; O’Cathain et al., 2019).

Participant recruitment and selectionRecruitmentAdvertising materials tailored to patients and clinicians, including eligibility criteria, contact information, and QR codes to the study website (https://insomniaresearch.com.au/) were distributed within the geographical footprint of the University of Newcastle. Interested participants could learn more about the research and register their interest to participate.

Insomnia group selectionCommunity-dwelling adults aged 18–65 years with self-reported insomnia symptoms, characterised using DSM-5 nosology: (i) difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or experiencing nonrestorative sleep, characterized by either frequent awakenings or difficulty returning to sleep after awakenings or early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep, occurring for at least 3 months or more, (ii) associated with clinically significant distress or impairment and occurring 3+ nights per week, (iii) occurring despite adequate opportunity for sleep, (iv) not attributable to an underlying medical condition (e.g., sleep apnoea, restless leg syndrome), psychiatric (e.g., major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder), or the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., alcohol, medication) were eligible to participate.

Inclusion criteria were evaluated using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Bastien et al., 2001; C. Morin, 1993) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989). The ISI provides a measure of symptom severity (range 0–28). Insomnia severity is classified as ‘not clinically significant’ (0–7), ‘subthreshold clinical insomnia’ (8–14), ‘moderate to severe clinical insomnia’ (15–21), and ‘severe clinical insomnia (22–28). The PSQI is a composite measure (range 0–21) of sleep quality, latency (i.e., time to fall asleep), duration, efficiency (i.e., proportion of time in bed vs time asleep), disturbance, functional impairment, and use of sleep medication during the previous month. Higher scores on both measures are indicative of greater impairment. An ISI score ≥10 and a PSQI ≥5 is commonly adopted cut-off scores for clinically significant insomnia in community samples and were employed in this study.

Survey responders with an ISI ≥10 and a PSQI ≥5 completed 2 additional validated measures, namely the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C) (Bush et al., 1998) to exclude prospective participants with problematic alcohol use (score ≥4 (men) and ≥3 (women) and current suicidal ideation using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001). The PHQ-9 is a multipurpose measure of depression severity in the past 2 weeks (range 0–27). Depression is classified as minimal (1–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (20- 27). Question 9 is a single screening binary question for current suicide risk – if positive indicates the need for additional assessment and screening.

Clinician group selectionClinicians were identified using the publicly available Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (APHRA) register. Clinicians practising within the geographical footprint of Newcastle, were contacted by a member of the research team and invited to participate. There were no exclusion criteria.

Data collection and proceduresParticipants attended a structured 2-hour in-person facilitated group discussion designed to capture comprehensive stakeholder perspectives on the acceptability and clinical utility of VR mindfulness for the treatment of insomnia. Focus group discussions were recorded, anonymised verbatim transcripts were analysed, and themes were generated.

Sessions included group consenting, pre-VR discussion, VR equipment familiarisation, individual app exploration, post-VR surveys, and a follow-up group discussion. Post-exposure reflections examined usability, engagement, and acceptability, supported by validated self-report measures, with sessions concluding with identification of perceived barriers and facilitators to adoption. This multi-component approach ensured participants could evaluate VR mindfulness technology through direct experience while providing both individual perceptions and group-generated insights about implementation potential.

Focus groupsIn line with similar studies, (Greenhalgh et al., 2017; Huygelier et al., 2019; Shiferaw et al., 2020) patients (Bierbaum et al., 2020; Ogeil et al., 2020) and clinicians (Liu et al., 2020) attended separate sessions to minimise power dynamics, facilitate open dialogue, and ensure participants felt comfortable expressing their views (Cedeno et al., 2019; Yule, 2024). This approach reflects best practice in implementation and digital health research, which recommends exploring the distinct—and sometimes competing—perspectives of stakeholder groups separately to generate more contextually relevant insights (Damschroder et al., 2009; Greenhalgh et al., 2017)

To support this separation of stakeholder groups, group-specific discussion guides before and after the hands-on activity were developed (Amestoy Alonso et al., 2024; Berardi et al., 2024; Brantnell et al., 2023; Seegan & McGuire, 2024). Patients were encouraged to share the impact of chronic insomnia on daily life, and beliefs, expectations, and motivations towards treatment, in addition to experiences of seeking or gaining access to treatment. Clinicians were invited to begin by discussing their approach to the evaluation and management of insomnia as well as their experience of incorporating DHTs into clinical care. These initial discussions established baseline perspectives before participants engaged with the VR technology.

Hands-on exploration of VR mindfulnessA central component of each focus group was structured, individual hands-on exploration of four commercially available VR mindfulness applications. The purpose of this experiential approach was to enable patients and clinicians to move beyond abstract, hypothetical or second-hand assumptions of VR mindfulness in the context of insomnia treatment to authentic, nuanced, and contextually relevant insights about the acceptability, utility, and potential implementation challenges.

Applications were selected based on: (1) commercial availability, (2) cost accessibility (free or low-cost), (3) variation in immersion levels, and (4) prior use in research settings. This approach enables replicability and transparency of findings. Moreover, these applications have been used in other studies, enabling researchers to contribute to the VR mindfulness literature in a novel context. The applications selected were Guided Meditation VR (Cubicle Ninjas, USA, available from www.guidedmeditationvr.com) (Failla et al., 2022; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2024); Liminal VR (Liminal VR,Australia, available from www.liminalvr.com) (Barton et al., 2020a), Place (Mental Health Online, Australia, available from www.mentalhealthonline.org.au/) (Jo et al., 2024; Seabrook et al., 2020), and Tripp VR (Tripp Inc., 2019, USA, available from www.tripp.com) (Housand et al., 2024). Fig. 1 shows still images of the VR mindfulness environment as viewed from the VR headset and Table 1 summarises the apps level of immersion (full or semi) and interactivity (low to high).

Still images of the interactive VR mindfulness environment as viewed from the VR headset for each of the four applications participants interacted with (a) Place (Mental Health Online, 2022); (b) Liminal VR (Liminal VR), (c) Guided Meditation VR (Cubicle Ninjas, 2021); and (d) Tripp VR (Tripp Inc., 2019).

VR mindfulness applications level of immersion and interactivity.

| Application | Immersion | Interactivity | Developers | Available From | Prior Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Semi immersive | Low | Mental Health Online, 2022, Australia | www.mentalhealthonline.org.au | (Jo et al., 2024; Seabrook et al., 2020) |

| Liminal VR | Fully immersive | Low to moderate | Liminal VR, 2022, Australia | www.liminalvr.com | (Barton et al., 2020b) |

| Guided Meditation VR | Fully immersive | Low to moderate | Cubicle Ninjas, 2021, USA | www.guidedmeditationvr.com | (Failla et al., 2022; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2024) |

| Tripp VR | Fully immersive | Moderate | Tripp Inc., 2019, USA | www.tripp.com | (Housand et al., 2024) |

Guidance and instruction were provided on the use of the Oculus Quest (Meta), a freestanding VR headset with 2 handheld controllers and an inside-out tracking system. Each participant was then provided with an Oculus Quest (Meta) headset and headphones to individually explore the four VR mindfulness applications. Participants were given additional one-on-one support as needed. Participants spent approximately 10 min exploring each VR mindfulness application. This hands-on experience formed the foundation for the quantitative assessments and subsequent group discussions.

This hands-on experience was immediately followed by standardized assessments of each application's acceptability. To evaluate key dimensions of acceptability and user experience of the VR mindfulness applications, we developed a study-specific questionnaire adapted from the System Usability Scale (SUS) (Brooke, 1995), User Experience Questionnaire, (Laugwitz et al., 2008) and Presence Questionnaire (PQ) (Witmer & Singer, 1998; Witmer et al., 2005). Each item was rated using a scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”).

Quantitative measuresBuilding on the experiential component described above, patients and clinicians completed quantitative assessments both before attending the focus group and immediately after the hands-on activity. Participants were asked if VR mindfulness would be helpful and effective for insomnia at both time points. This pre-post design enabled evaluation of how direct familiarity with VR technology (Greenhalgh et al., 2017) affected perceived acceptance (Pallesen et al., 2018) and utility (Huygelier et al., 2019) thereby supporting the validity of the qualitative findings.

To further contextualise and enrich interpretation of the qualitative themes from the focus group discussions, additional quantitative data were collected prior to the sessions. These baseline measures included demographics, education, socioeconomic status, employment, medical/psychiatric history (yes/no; and year/age of diagnosis patients only), professional background, clinical setting, and years of experience (clinicians only), propensity for motion sickness (triggers/frequency), personally use DHTs (yes/no; and type e.g., running app), incorporate DHTs in clinical practice (clinician only), and prior experience with VR technology (yes/no; and amount of time spent using the technology). This comprehensive data collection approach ensured that both experiential insights and contextual factors could be integrated in the analysis. All quantitative measures were collected online using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) (Harris et al., 2019).

Sample sizeThis study did not aim to generalise findings or establish causal inference; accordingly, no power analysis was conducted. The target sample size aligns with established qualitative research standards, which emphasise thematic depth over statistical generalisability (O’Brien et al., 2014). Literature suggests that 3 to 6 focus groups is sufficient to identify 80–90 % of emergent themes (Guest et al., 2017). However, best practice for emerging technology research involving hands-on interaction recommends smaller groups of 2–3 participants to support both meaningful discussion and effective experiential engagement with the technology (Tuena et al., 2020).

To accommodate these smaller group sizes while achieving adequate thematic saturation, a larger total number of focus groups was planned. With 2–3 participants per group, 8–10 patient focus groups (targeting 16–30 total patient participants) and 2–4 clinician focus groups (targeting 4–12 total clinician participants) were deemed necessary to reach the equivalent thematic coverage typically achieved with 3–6 larger focus groups.

Given the study's focused scope and purposive sampling of relatively homogeneous stakeholder groups (i.e., individuals with chronic insomnia and clinicians familiar with the clinical context), thematic convergence and conceptual depth are anticipated across this distribution (Hennink et al., 2019; Nelson, 2017). A larger number of patient groups relative to clinician groups was planned to account for the greater heterogeneity in patients' first-person experiential perspectives, which are often more diverse and individualized. In contrast, clinicians—particularly within a single profession or service setting—tend to provide more homogeneous perspectives (Tausch & Menold, 2016). A smaller, diverse clinician sample is thus considered sufficient to capture key implementation concerns (Adanijo et al., 2021).

Data analysisQualitative data analysisA qualitative analysis using inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2012) to explore the distinct experiential perspectives of patients as recipients with a personal, lived experience perspective and clinicians as providers of care, on VR mindfulness as a potential novel digital health intervention for insomnia. Qualitative data were analysed using a Framework Approach (FA) supported by VERBI Software. FA is a qualitative research method particularly suited for applied policy research and studies with specific questions and limited timeframes (Srivastava & Thomson, 2009). FA was selected over other qualitative approaches because it accommodates both deductive analysis of pre-established constructs from the TAM (Davis, 1989) and inductive exploration of emergent themes from participants' experiential accounts. Unlike purely inductive approaches such as interpretative phenomenological analysis, FA's structured framework enables systematic comparison between distinct stakeholder groups (patients vs. clinicians) while maintaining flexibility for novel insights to emerge. It involves five key steps: familiarization (via a thorough and iterative review of interview transcripts and field notes), identifying a thematic framework (synthesis of pre-established issues from the group-specific discussion guide with emergent themes by individual respondents), indexing (systematically applying a thematic framework to identify and code relevant text), charting (summarized and reorganized into headings and subheadings), and mapping and interpretation (identification of relational patterns and emergent themes) (Parkinson et al., 2016). FA guides the manual codification of qualitative data whilst supporting inductive and deductive evaluations of the data, including a priori research questions. FA provides a clear audit trail, enhancing the credibility and transparency of qualitative research (Somerville et al., 2023). The systematic, iterative, and sequential process FA supports was followed to identify and organize codes into categories and themes (Clarke & Braun, 2017). To maintain confidentiality; participants were assigned a code; a letter P or C (i.e. patient, clinician); gender (male: M; female: F), age, insomnia severity/chronicity, and clinical training (i.e., GP, clinical psychologist, psychiatrist) practice setting (i.e., community, private practice), and experience (early, mid, late career).

Age and gender were retained in participant coding to enable analysis of potential differences in technology acceptance, given established age and gender differences in insomnia prevalence, chronicity, treatment-seeking behavior, and mindfulness engagement. Socioeconomic factors (income, education, employment status) were analyzed thematically in relation to technology accessibility and acceptability concerns. Anonymized sample quotes are presented to illustrate how raw text was grouped and organized and how minor and major themes emerged (Fossey et al., 2002). Final themes and subthemes were developed through a reflexive and iterative process and comparative in-depth discussion by at least 2 researchers until a consensus was reached. Participants were sent a summary of the themes and asked for their feedback.

Quantitative data analysisThe quantitative data—demographics, education, employment, socioeconomic status, clinical history, prior digital health exposure, and pre–post ratings of the perceived acceptability and utility of VR mindfulness for insomnia were exported from REDCap and imported to IMB SPSS (version 29.0). Mean score ratings (pre-to-post) were analysed using a two-tailed, non-parametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests, graphical representations constructed using GraphPad Prism (version 10). Direct group comparison was not the study’s aim. Therefore, only within-group changes were examined.

Synthesis of qualitative and quantitative dataSeparate analyses of patient and clinician focus group discussions and survey responses were conducted. Qualitative data analysis included an evaluation of areas of convergence and divergence between patient and clinician perspective on the clinical utility of VR mindfulness during the focus group discussion. This process has been shown to reveal important insights that would not have emerged from either group alone. Quantitative data were used to contextualise and enrich interpretation of the qualitative themes, rather than to test hypotheses or draw inferential comparisons.

ResultsA total of 15 focus groups—10 insomnia patients only and 5 clinician only, with 33 participants—19 patients and 14 clinicians enabled us to reach theoretical sufficiency—the point at which no substantively new themes emerged (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2019).

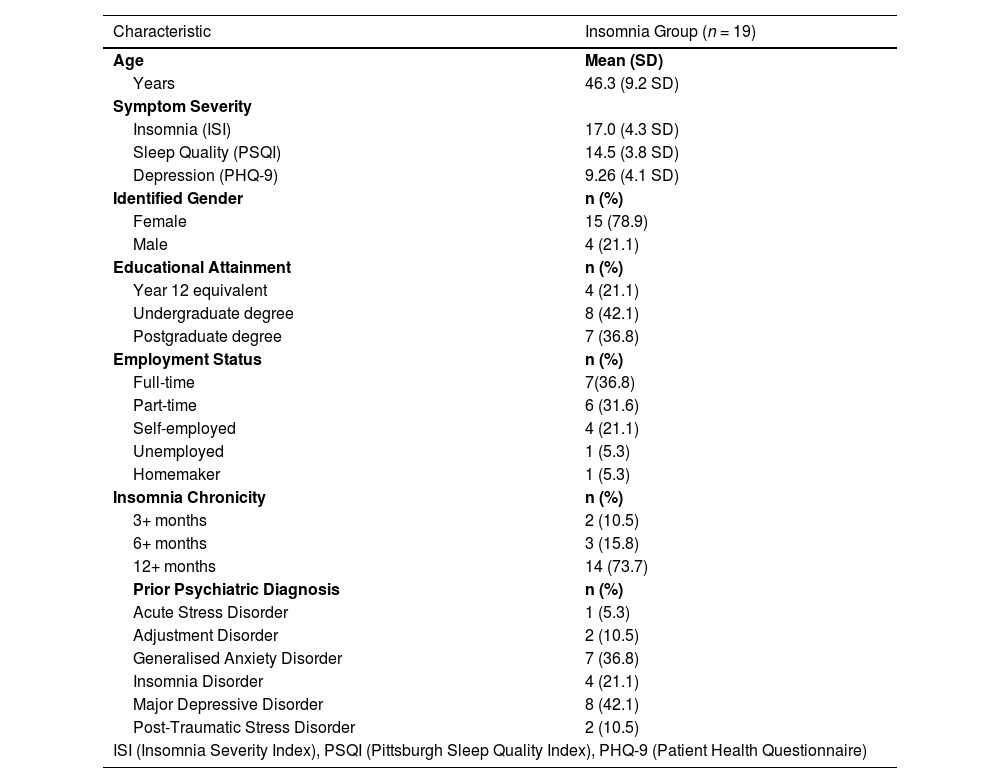

Participant characteristics and baseline measuresInsomnia groupDemographics and baseline measuresDemographic information of the 19 patients (4 males, 15 females) with chronic insomnia in the moderate to severe range (mean ISI 17.5 (SD 4.3) and PSQI 14.46 (SD 4.2), who attended the patient only focus groups are shown in Table 2. Patients had a mean age of 46.3 years (SD9.2, range 27–65), mild depression (PHQ-9 mean 8.32 (+ 4.1); 73.7 %, n = 14) reported insomnia symptoms for >12 months and 21.1 % (n = 4) had a prior diagnosis of ID, comorbid with anxiety (n = 1) or depression (n = 3). Educationally, 21.1 % (n = 4) completed secondary education, 42.1 % (n = 8) attended college/university, and 36.8 % (n = 7) had graduate/postgraduate degrees; 85 % (n = 17) were employed and the remainder either unemployed (n = 1) or homemakers (n = 1).

Patient demographics and symptom severity (quantitative data).

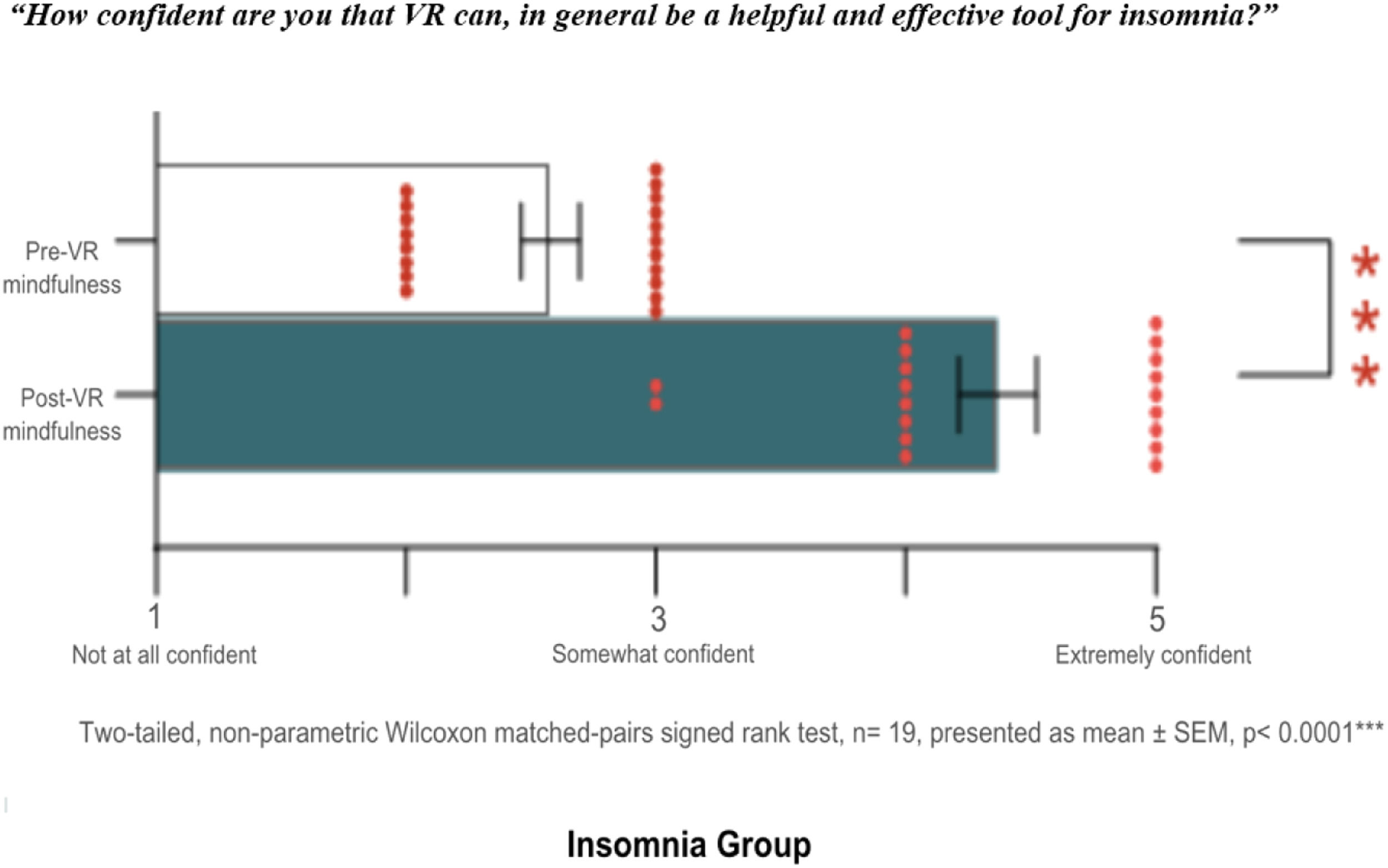

Prior to attending the focus groups patients were "Very" or "Extremely familiar" with DHTs (57.9 %, n = 10) with DHTs, reporting the use of lifestyle apps to track fitness (88.9 %, n = 8) or diet and nutrition (22.2 %, n = 2). A total of 63.2 % (n = 12/19) reported no prior VR experience. The 36.8 % (n = 7) with prior VR experience, stated very limited exposure (less than 1 h total) and almost exclusively in a gaming context. One insomnia patient managed a VR event entertainment business. None had any prior experience of VR mindfulness. Patients expressed curiosity (78.9 %, n = 15/19) and excitement (15.8 %, n = 3/19) about the potential of trying VR mindfulness. At baseline perceptions of the potential acceptability and usability of VR mindfulness for insomnia (i.e. “How confident are you that VR can, in a general context, be a helpful and effective tool for insomnia?” on a scale of 0 to 5) were modest, mean confidence was 2.58 (n = 19).

Clinician groupDemographics and baseline measuresThe 14 clinicians (10 female, 4 male) had a mean age of 43.93 years (SD = 12.01, range 26–64). They reported an average of 15.14 years (SD = 12.18, range 1–44) of clinical experience across community mental health clinics (71.4 %), private practice (14.3 %), and public hospitals (57.1 %). Many worked in multiple settings and held various specializations, resulting in percentages exceeding 100 % (Table 3).

Clinician demographics.

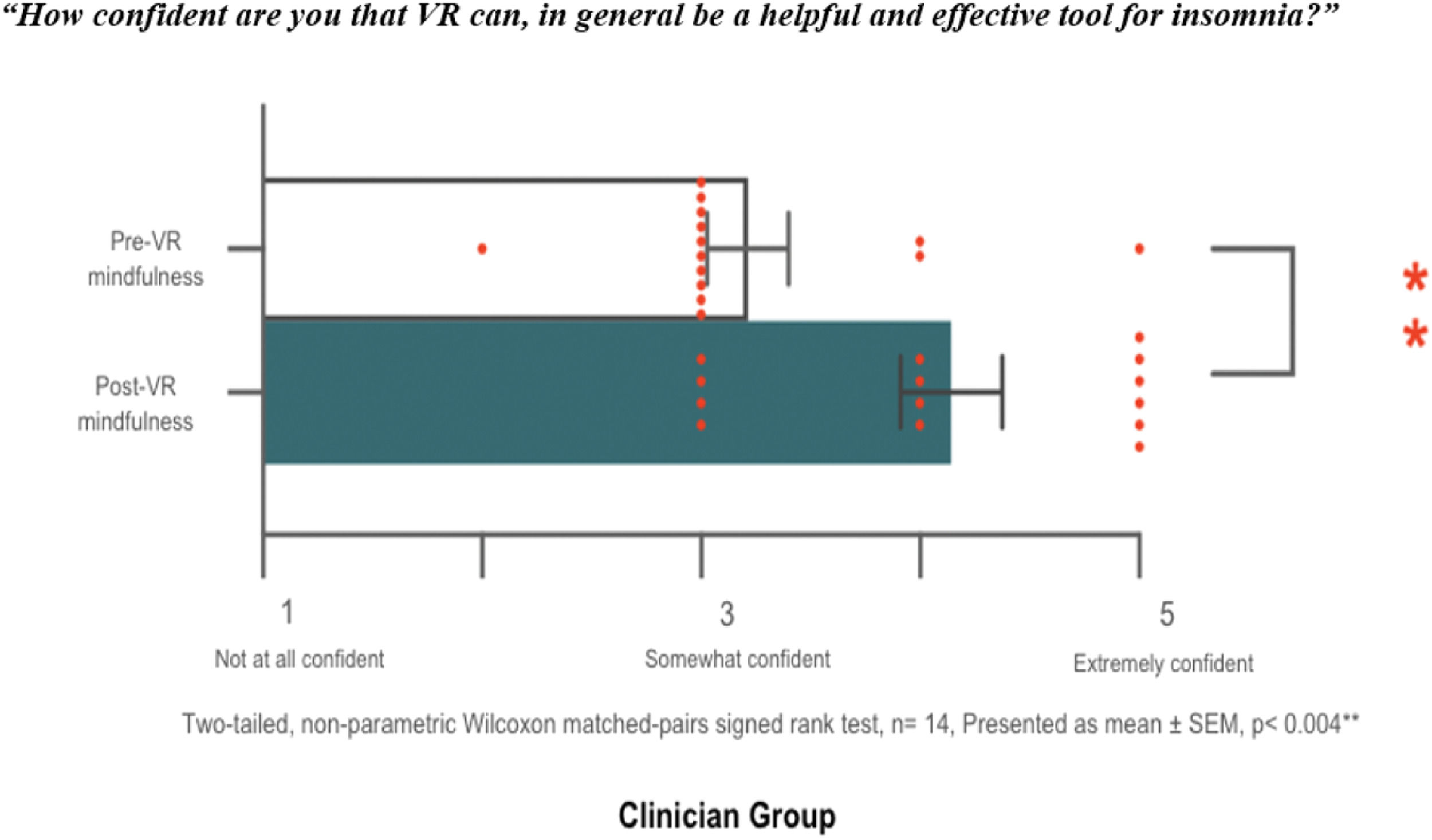

Prior to attending the focus group 42.8 % (n = 6/14) of clinicians were "Very" or "Extremely familiar" with DHTs, with 57.1 % (n = 7/14) reporting routine use of DHTs in clinical practice principally to support mood tracking and behaviour modification. A total of 42.8 % (n = 6/14) reported no prior VR experience. The 57.1 % (n = 8) who reported prior experience of VR experience, stated limited exposure (less than 2 h total). One clinician reported using VR clinically to treat phobias. None had experience of VR mindfulness. Clinicians were also curious (64.3 %, n = 9/14) and excited (35.7 %, n = 5/14) about exploring VR mindfulness. Clinicians baseline perceptions of the potential acceptability and usability of VR mindfulness for insomnia were positive, mean confidence was 3.86 (n = 14).

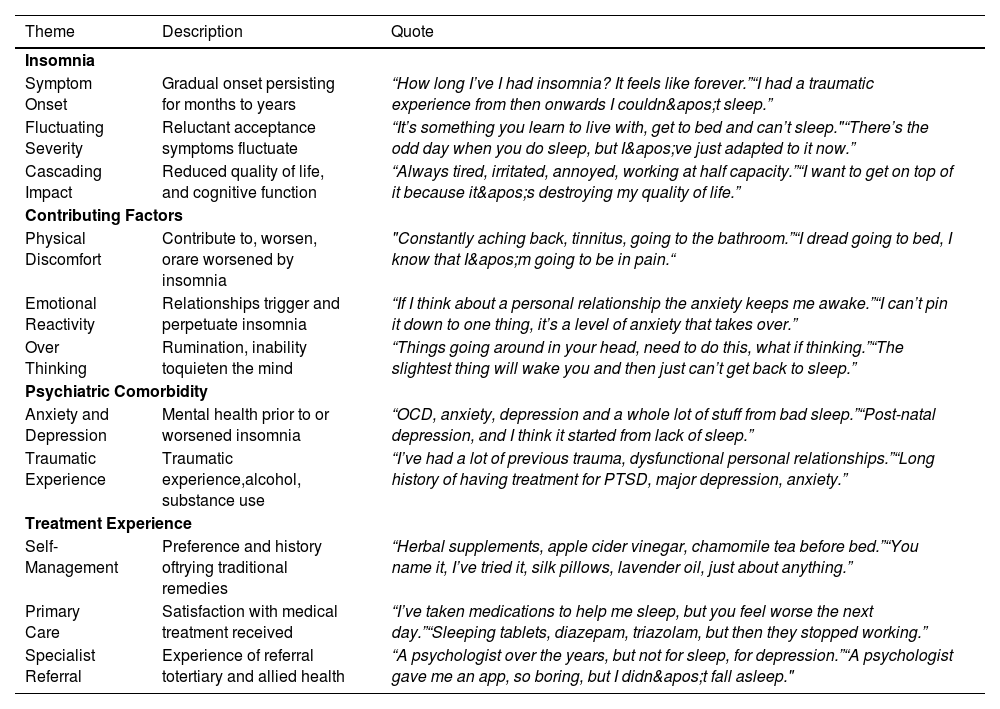

Focus group findings acceptability and utility of VR mindfulnessInsomnia groupThemes before VR mindfulnessDuring the focus groups patients recalled a longstanding history of insomnia and reduced quality of life (e.g., irritability, reduced productivity, cognitive impairment), describing it as “something you learn to live with” [Patient 08]. Interestingly, some patients (n = 7/19) did not consider themselves as having "insomnia” but equated it with “never sleeping” or “staying up all night”, instead describing themselves as “I’ve got trouble falling asleep” or “My problem is I can’t get back to sleep” (Table 4.). Treatment strategies included an array of self-management (e.g., herbal supplements, relaxation, distraction, sleep hygiene) strategies in conjunction with sleep medication (e.g., sedating antihistamines, benzodiazepines, antidepressants). Frustration and dissatisfaction with available pharmacological treatments were common. Concerns about the safety of pharmacological treatments and the efficacy of non-medication options were reasons why some (n = 9/19) did not seek treatment. During the discussion (n = 10/19) Patients who sought treatment from a healthcare provider, many recalled referrals to tertiary services for depression and anxiety, but not insomnia. One participant self-selected to complete an internet-delivered CBTi program for insomnia history (Table 4).

Patients lived experience of insomnia, its impact, and treatment history.

Patients had a nuanced understanding of mindfulness the majority (n = 14/19) reported having tried mindfulness in some form or other. During the facilitated discussion some reported practising mindfulness regularly, describing it as “relaxing,” “enjoyable,” and “helpful” in managing stress and anxiety; others found it “boring” and seldom practised. The use of mindfulness “to get to sleep” was reported by several (n = 12) patients, some described it as “pointless” and “annoying” or providing “no benefit” (n = 7/19) others found it was “sometimes helpful” (n = 5/19). During the focus group discussions several reported used audio-based apps, mainly for sleep onset, reporting limited benefits but continued use because it “helps pass the time while you wait to fall asleep” [Patient 03]. Meditation apps (e.g., Calm, Smiling Mind) were also used, again with mixed benefits—some reported faster sleep onset with the qualifier “but it still takes an hour, mental chatter is still there” [Patient 09].

Themes after VR mindfulnessAfter using VR mindfulness patients described it as “easy to use” and more engaging “compared to say a guided audio meditation” [Patient 12]. Patients suggested VR might be helpful to learning and practising mindfulness, and as a way to make mindfulness more accessible to certain populations (e.g., police force and emergency services). Patients described VR “as enhancing the experience” because “it helps you escape to a place that's yours” [Patient 16]. Many expressed willingness to recommend VR mindfulness to others with insomnia, regardless of age. Notably, it made patients who had considered mindfulness for sleep, “boring” or “annoying”, willing to try mindfulness for insomnia again (Table 5).

Patients’ perceptions of VR mindfulness before and after the hands-on exploration.

After trying VR mindfulness, participants perceptions of the potential acceptability and usability of VR mindfulness for insomnia increased to 4.37 (n = 19) from 2.58 (scale 0–5), with 89.5 % (n = 17) being “very” or “extremely” confident that VR mindfulness would be a helpful and effective tool at remediating their insomnia symptoms. The changes in patients perceived acceptability and utility of VR mindfulness were found to be statistically significant (Wilcoxon within groups signed-rank test p<.0001, n = 19; Fig. 2).

Within group changes in patients' attitudes towards the helpfulness and effectiveness of VR mindfulness. Responses on a 5-point scale to the question “How confident are you that VR can, in general be a helpful and effective tool for insomnia?” collected pre- and post-app exploration from A). Individual responses are presented as red dots with the mean plus minus SEM. ** indicates p<.0001 (n=19).

Clinicians in community and hospital settings reported a substantial need for effective management of insomnia, describing it as potentially greater than that of depression. Regardless of the clinical setting, the high prevalence of insomnia and comorbidity with physical and psychiatric disorders pose substantial treatment challenges. Table 6. includes a selection of sample quotes of clinicians’ experience of insomnia management. Clinicians described dedicated insomnia treatment was rare, and typically only provided when sleep disturbances significantly impacted other health issues. In those instances, treatment consisted of sleep hygiene and “psychoeducation around energy drinks and coffee” [Clinician 12]. Very occasionally, time permitting some clinicians “might use sleep restriction, maybe some routine structuring, because it's usually quick and discreet” [Clinician 18]. Mindfulness was predominantly used as an adjunct to other treatments rather than as a standalone intervention. Clinicians expressed interest in using it more frequently, but face barriers, including time constraints, perceived ineffectiveness (by clinicians and patients), and the challenges of learning mindfulness itself.

Clinicians’ experience of insomnia management.

During the focus group discussion in the context of insomnia clinicians reported very occasional and selected use of DHTs, namely sleep diaries; citing inconsistent use (e.g., “I don't think I've ever had anyone do it" [Clinician 18]) and patient disorganisation, with some completing diaries only in waiting rooms

Themes after VR mindfulnessTable 7 includes a selection of quotes to illustrate clinicians’ perceptions of VR mindfulness during the focus group discussion before and after the hands-on exploration. Some clinicians were concerned about the suitability of VR, stating “it's probably not suitable for many patients, too stimulating” [Clinician 06], particularly “older people”. Interacting with VR mindfulness appeared to assist clinicians to recognise the clinical utility of VR as a therapeutic tool in “the clinical space” [Clinician 02] in the context of insomnia and beyond. The capacity for personalized and customized environments was seen as a “better way to engage patients” and “on-ramp" to traditional mindfulness [Clinician 02]. Clinicians anticipated strong interest from patients. The self-guided aspect of VR mindfulness made the intervention particularly acceptable to clinicians from a scalability perspective, because “we’ll never have enough clinicians or practitioners” [Clinician 08] and “it’s hard to explain how to do mindfulness, it takes time” [Clinician 11].

Clinicians' perceptions of VR mindfulness before and after the hands-on-exploration.

Clinicians’ confidence also increased after the hands-on activity, with 71.4 % (n = 10) becoming "very" or "extremely" confident of the potential acceptability and utility of VR mindfulness in the context of insomnia. Mean score was 4.28 (n = 14) from 3.86 (scale 0–5). The change in clinicians mean confidence was statistically significant (Wilcoxon within groups signed-rank test p < .004, n = 14; Fig. 3).

Within group changes in clinicians’ attitudes towards the helpfulness and effectiveness of VR mindfulness. Responses on a 5-point scale to the question “How confident are you that VR can, in general be a helpful and effective tool for insomnia?” collected pre- and post app exploration from A). Individual responses are presented as red dots with the mean plus minus SEM. ** indicates p<.0041 (n=14).

Patients and clinicians demonstrated convergence in recognising insomnia as a prevalent and chronic condition, frequently comorbid with psychiatric and physical health concerns. Both groups acknowledged the limitations of pharmacological management and the restricted feasibility of delivering other evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments. Divergence emerged in the prioritisation and framing of insomnia within complex clinical presentations. Clinicians often described insomnia as secondary to broader mental health or psychosocial concerns, such as trauma or substance use, whereas patients emphasised its disruptive impact on daily functioning and well-being. One patient reflected, “It’s destroying my quality of life,” highlighting the centrality of sleep disruption in their subjective distress. In contrast, a clinician noted, “So much dysfunction, so many needs, they’ve got bigger problems than sleep,” illustrating the tendency to deprioritise sleep difficulties in the context of broader care demands.

Clinicians described what they perceived as a strong patient preference for immediate insomnia relief, often framed as pressure to prescribe. One clinician remarked, “People are desperate to sleep. Give me a pill. Fix it” highlighting the urgency and expectations frequently conveyed in clinical encounters. In contrast, patients reflected on the limitations and undesirable side effects of long-term medication use, with one noting, “I’ve taken medications to help me sleep, but you feel worse the next day.” This tension between clinicians perceived patient demand for pharmacological management of insomnia and patient experience suggests a potential disconnect in treatment expectations, underscoring the importance of accessible, acceptable non-pharmacological alternatives. While clinicians emphasised lack of patient interest in mindfulness due to limited efficacy and systemic barriers to delivering mindfulness-based interventions, such as time and resource constraints, patients described extensive efforts to self-manage their symptoms, including the use of mindfulness, but reported limited success. Suggesting that approaches to facilitate mindfulness as both clinicians and patients stated would be welcome.

After VR mindfulnessPatients and clinicians had relatively similar perceptions of VR mindfulness before the hands-on exploration. Irrespective of prior use, VR was perceived as “high-tech” and “futuristic” by patients and clinicians. The majority assumed VR was prohibitively expensive and complicated to use. All anticipated VR mindfulness was to be used before bed, with several expressing concerns about “having something on my face when I’m trying to sleep” [Patient 9] and the impact on sleep from the device’s light, “after all we’ve been told about turning off our phones” [Patient 11]. All expressed surprise that VR mindfulness could be used at any time.

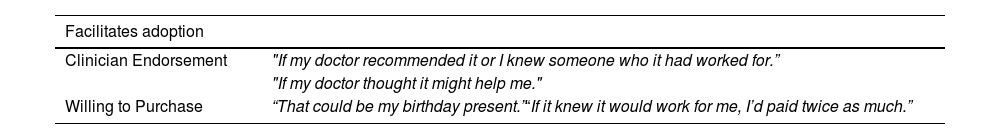

Focus group findings barriers and facilitators to adoptionInsomnia group themesThe hands-on exploration served to address misconceptions about VR and to illustrate its potential. Table 8 provides a sample quotes of patients perceived barriers and facilitators to the adoption of VR mindfulness. Patients expressed curiosity and surprise at the cost of VR mindfulness, some were willing to “invest in my health” and buy a VR headset whilst others were concerned if it was “another gimmick”. Surprisingly for the majority of patients, cost was not a barrier to adoption, one stating, “That could be my birthday present” [Patient 12]. Many considered the equipment bulky and heavy, describing it as the “brick mobile phone of the 80s”, but anticipated improvements in the near future. Several were unsure “which VR mindfulness app to get” and in the absence of a clinical recommendation encouraged to hear that most VR mindfulness applications include a ‘free’ limited offering version. A recommendation from their healthcare provider was of greater importance and increase the likelihood of adoption.

Patients perceived barriers and facilitators to the adoption of VR mindfulness.

Clinicians were enthusiastic about VR mindfulness, one clinician stating, "I don't think you'd have any trouble with us prescribing, all we need is access” [Clinician 18]; 98 % (n = 13/14) agreed that contingent on its feasibility, incorporating VR mindfulness into clinical practice would immediately improve patient care. The perceived safety and tolerability of VR mindfulness and the ability to use commercially available VR headsets and VR mindfulness apps increased clinicians' interest in adopting the technology (Table 9). Several seeing it as “very simple and easy to implement” [Clinician 11]. Clinicians identified several challenges to implementing VR mindfulness, both from their perspectives and those of their patients (Table 9). These concerns, while not unique to VR mindfulness, reflect broader issues clinicians often encounter when introducing new healthcare initiatives in publicly funded healthcare systems, particularly those involving technology. Key challenges included equipment maintenance and replacement, patient affordability, and digital literacy. Clinicians anticipated needing information on the “practical side of prescribing a treatment" [Clinician 18], including where to access, app selection, frequency and duration of sessions, and timing. Clinicians also envisaged the need for practical advice on “what treatment looks like in a session” [Clinician 01] and "hearing how others use in clinical practice and for whom” [Clinician 12].

Clinicians' perceived barriers and facilitators to the adoption of VR mindfulness for insomnia.

Both patients and clinicians identified key factors likely to influence the uptake of VR mindfulness interventions for insomnia. There was convergence in recognising the role of comfort and device design in shaping user experience. Participants across both groups described discomfort as a potential barrier to sustained use. A patient noted, “It does take a bit of getting used to that big boxy thing on your face” while a clinician similarly reported, “The heavy headset distracted from the mindfulness experience.” These concerns indicate that physical ergonomics are a shared determinant of user acceptability.

A notable divergence emerged between clinicians and patients concerning assumptions about who would be willing or able to engage with VR mindfulness. Several clinicians expressed concerns about accessibility, suggesting the intervention may not be appropriate for certain populations. One clinician remarked, “Probably not suitable for older people,” and another reflected on socioeconomic barriers, stating, “I had someone say they couldn't even afford the bus.” These views imply anticipated challenges in adoption based on age and financial hardship. In contrast, patients themselves reported openness across demographic lines, with one stating, “I’d recommend it to my dad. I think he’d really like it,” suggesting intergenerational applicability. Furthermore, enthusiasm was not necessarily constrained by cost, as reflected in the view that “Honestly, if I knew that it would work for me, I wouldn't care if it cost twice that” (Patient 8). This mismatch indicates that clinicians may overestimate certain structural barriers or underestimate patient motivation and perceived value of novel interventions.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly evaluate the utility and acceptability of VR mindfulness for insomnia from the perspective of clinicians and patients with chronic insomnia before and after direct, hands-on experience with four commercially available VR mindfulness applications. Our findings demonstrate that experiential exposure significantly increased acceptability among both patients and clinicians, moving beyond hypothetical perceptions to evidence-based insights.

Clinicians and patients welcomed the possibility of a new treatment for insomnia, welcomed the prospect of having immediate access to it, as the VR mindfulness applications and equipment needed for its use are readily available. Consistent with previous findings, insomnia was associated with reductions in overall functioning and quality of life (Ogeil et al., 2020). Patient dissatisfaction with available treatment options and preference for self-management contributed to a reluctance to seek treatment—findings that are consistent with prior findings (Sandlund et al., 2018). Clinicians confirmed that, as previously reported, insomnia is both highly prevalent and comorbid with other medical and psychiatric disorders, resulting in treatment challenges. Insomnia treatment was seldom prioritised by clinicians, as others have previously reported (Sake et al., 2019). Clinicians cited competing treatment needs and limited opportunities to implement behavioural interventions as reasons for sidelining or postponing its treatment—findings that reflect a broader trend of under-treatment for insomnia in Australia and elsewhere (Ree & Richardson, 2021). When treatment occurred, it typically consisted of psychoeducation; clinicians rarely reported using other CBTi components (e.g., stimulus control, sleep restriction) (Walker et al., 2022). Mindfulness was seldom part of routine clinical care unless included in an existing treatment protocol. In the context of insomnia, mindfulness was very rarely used, either as an adjunctive or standalone treatment for insomnia. Possibly, because MBIs were perceived as having limited immediate utility or as ineffective by both clinicians and the communities they serve.

Lack of familiarity with DHTs is a known barrier to their adoption (Greenhalgh et al., 2017; Kessel et al., 2023). This barrier manifests in various ways, including perceptions of complexity and lack of trust in digital health solutions that result in a general apprehension towards trying new technologies. In the context of VR, which 95 % (eSafety, 2023) of Australians report having no prior experience using (Mathysen & Glorieux, 2021) the perception of VR as difficult to use and not suitable for insomnia is to be expected. In line with prior findings, interacting with VR had a significant positive impact on the attitudes and opinions of clinicians (Rimer et al., 2021) and the general public (Gomez Bergin et al., 2024). Despite limited familiarity and experience with VR, clinicians and individuals with insomnia demonstrated a high acceptance of the technology as a treatment delivery tool—a finding consistent with other evaluations of VR in a clinical or healthcare setting (Halbig et al., 2022; Shiner et al., 2024). The increasingly positive attitude, particularly of clinicians, is consistent with reports showing that the “clinician barrier” to clinical adoption is softening (Lindner et al., 2019).

Ease of use is also an important aspect for any treatment (Tuena et al., 2020). Clinicians and patients consistently reported that VR mindfulness was easy to use following just a few minutes of instruction. The immersive nature of VR mindfulness and the potential for individualisation of treatment was considered a key advantage (Vincent et al., 2021). The capacity of VR to enhance the physical benefits of MBIs is consistent with prior research showing that VR’s ability to block potentially distracting environmental stimuli facilitates the focused attention intrinsic to mindfulness.

Consistent with earlier research, clinicians noted the potential of VR to amplify the impact of traditional therapeutic approaches (Mao et al., 2024). A finding that is supported by patients reporting feeling relaxed and less stressed after briefly using VR mindfulness (Navarro-Haro et al., 2017). Clinicians commented that VR mindfulness not only addresses the shortage of mental health professionals but also empowers patients to engage in their treatment autonomously, fostering a sense of agency and control over their recovery process (Freeman, 2023), and is likely to lead to increased engagement in mindfulness activities outside of VR, as previously reported (Olarza et al., 2024). Clinicians considered VR mindfulness a potential adjunctive to existing treatments where mindfulness may be a component (e.g., DBT) (Gomez et al., 2017). Clinicians raised the possibility of VR mindfulness supporting insomnia management during withdrawal from alcohol and other psychostimulants (Skeva et al., 2021).

The cumbersome and bulky nature of current VR headsets was the primary barrier to adoption by clinicians and patients. Contrary to earlier reports (Gao et al., 2024a), technical anxiety around VR was not perceived as a substantive barrier to adoption. Consistent with previous findings, clinicians reported several practical challenges that could impede the integration of VR mindfulness into routine clinical practice (Chung et al., 2023) including the need for adequate training and ongoing support, funding, and treatment guidelines, particularly around optimal dose (Gao et al., 2024b).

Strengths and limitationsThis study employed focus groups as a formative, experiential method to explore the perceived acceptability, potential clinical utility, and feasibility of VR-delivered mindfulness for chronic insomnia. Rather than seeking empirical confirmation, the approach generated nuanced, socially situated insights into acceptability, usability, and implementation barriers, well suited to early-stage evaluation of novel digital interventions.

Although modest in size, our yielded conceptually rich data. Thematic convergence and interpretive depth were achieved across multiple focus groups, consistent with criteria for theoretical sufficiency in qualitative research. Although participants varied in prior VR exposure, all underwent structured, individualised hands-on exploration, minimising abstract or hypothetical biases and strengthening the credibility of reflections. The hands-on aspect of the study design moved participants beyond hypothetical appraisals to authentic, context-relevant feedback predicting real-world uptake.

The mixed-methods design strengthened interpretive depth. Quantitative ratings pre- and post-VR exposure complemented perceptions of helpfulness and effectiveness and tracked attitude shifts. Including both patients and clinicians provided a richer, multidimensional understanding of intervention acceptability. This approach aligns with digital health frameworks emphasizing early engagement of end users and implementation stakeholders to enhance translational value and ecological validity. This dual perspective enhanced ecological validity and revealed critical points of convergence, VR’s immersive quality as novel and therapeutic, that may facilitate mindfulness in the context of insomnia; but also, divergence, regarding who would be willing or able to engage with VR mindfulness, clinicians concerns that cost of VR equipment and digital literacy would be a barrier for patients were not consistent with patients’ perceptions.

While generally positive attitudes toward VR mindfulness for insomnia were reported, the limited diversity of the insomnia patients in terms of socioeconomic status and education, factors that shape perceptions of DHTs,mean findings may not reflect other populations with insomnia. Future studies should prioritise broader representation to assess equity and accessibility.

Although findings are exploratory, the barriers and facilitators to patient adoption and clinical integration of VR-delivered interventions identified in this study are consistent with the literature. However, our conclusion that VR mindfulness is an acceptable treatment for insomnia is based on a small sample of patients with chronic insomnia and clinicians familiar with its treatment and may not reflect the views of others.

ConclusionDespite growing evidence for VR mindfulness in treating insomnia, no prior research has explored barriers and facilitators to its adoption through direct stakeholder experience. This study demonstrates that hands-on exposure to VR mindfulness significantly increases acceptability among both patients and clinicians, moving beyond hypothetical assessment to experience-based insights. Patients reported willingness to use and recommend VR mindfulness, viewing it as a more engaging and accessible way to learn mindfulness. Key facilitators included healthcare provider endorsement and assistance in app selection. Clinicians perceived VR mindfulness as scalable and easily implementable, believing patient care would improve with its availability.

However, practical implementation challenges emerged. Clinicians anticipated needs for adequate training, ongoing support, funding, and treatment guidelines. For both stakeholder groups, headset size and weight represented the primary adoption barrier. Notably, while clinicians expressed concerns about patient affordability, cost was not perceived as a barrier by patients themselves, highlighting important divergence in stakeholder assumptions. These findings provide actionable guidance for VR mindfulness implementation and establish a methodological framework for evaluating emerging digital health technologies through experiential rather than theoretical assessment.

Future directionsFurther research is needed to harness the benefits VR mindfulness offers for delivery of and adherence to insomnia treatment and to address the logistical barriers to clinical adoption and implementation. Further research is needed to better understand the support and training clinicians may need to offer VR mindfulness as a treatment for insomnia. Research directly evaluating the feasibility, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of VR mindfulness are critical first steps toward the development of clinical practice guidelines—the cornerstone of successful integration into routine clinical care.

Authors have no interests to declare.