: Attentional bias towards threat is a core mechanism underlying posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although attention bias modification (ABM) and attention control training (ACT) have been studied for PTSD, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported inconsistent outcomes. Additionally, the nonemotional conditioning effect of ACT remains unvalidated. Shidu parents in China, a uniquely vulnerable group who have lost their only child, often suffer from severe and persistent PTSD, however, no RCT has yet investigated attention-based interventions among them. Thus, this RCT compared the efficacy of ABM, ACT, and attention control geometric training (ACG), which adapts ACT in a nonemotional context, on PTSD symptoms and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) activity among Shidu parents.

Methods: Participants were randomly assigned to the ABM (n = 21), ACT (n = 20), and ACG (n = 21) groups and completed eight biweekly sessions of ABM, ACT, and ACG, respectively. Symptoms, including PTSD clusters and anxiety as primary outcomes and PTSD total and depression as secondary outcomes, along with attentional bias were assessed at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and a four-month follow-up. DLPFC activity was measured using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) at pre-treatment, mid-treatment and post-treatment.

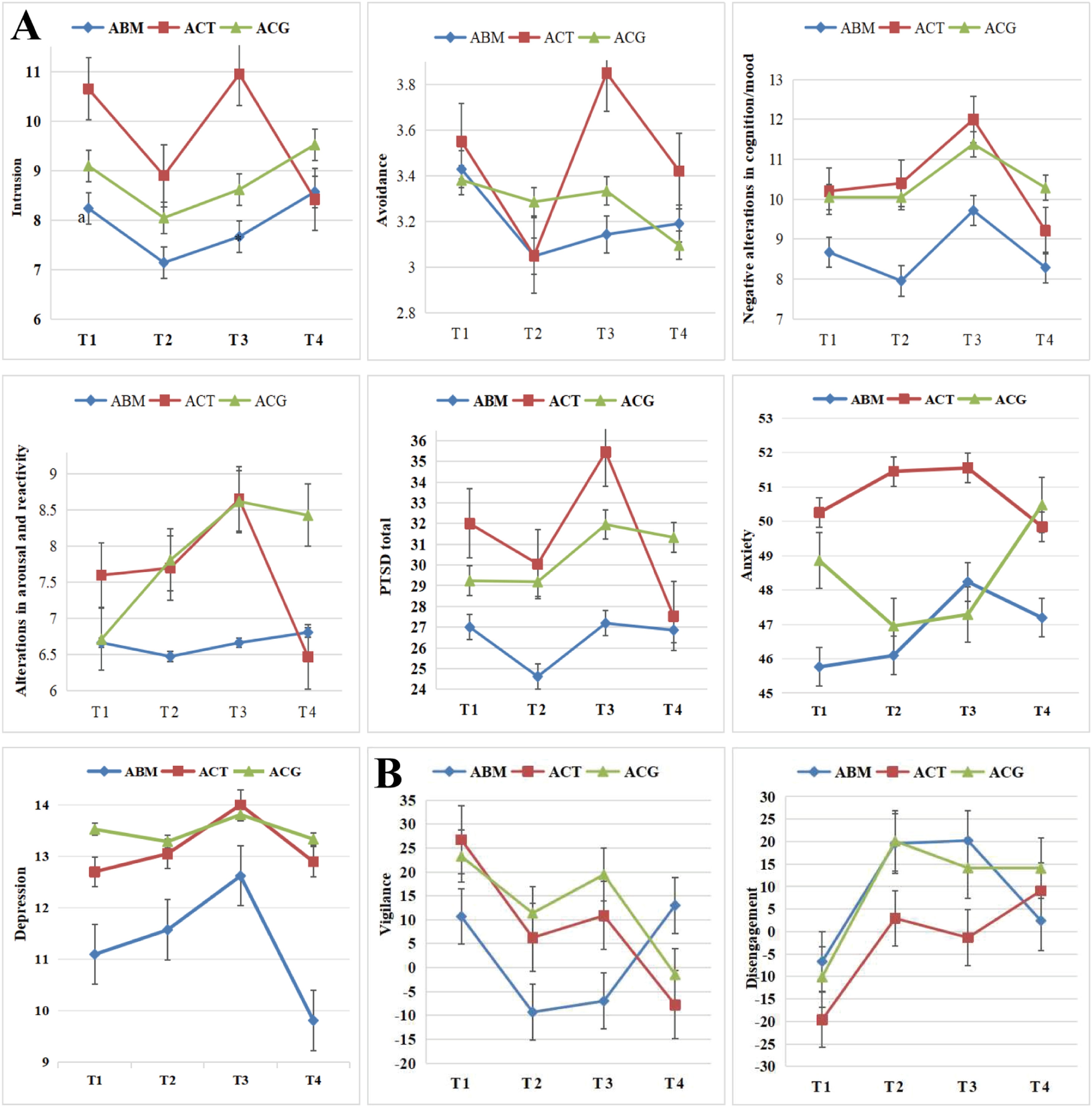

Results: ACT demonstrated significant improvement in intrusion symptoms, with treatment effects sustained at the four-month follow-up. However, other PTSD symptom clusters, as well as anxiety and depression, did not show significant improvement across any of the groups. At the neurocognitive level, ACT showed reduced vigilance toward threat and decrease in bilateral DLPFC activation under the vigilance condition. In contrast, ACG exhibited only a nonsignificant trend toward reduced vigilance to threat, along with reduction in left DLPFC activity under the same condition. ABM showed no significant improvements in either behavioral or neural measures.

Conclusions: This study provides preliminary evidence that ACT may be a promising intervention for reducing intrusion symptoms and threat vigilance in Shidu parents, potentially through modulating DLPFC activation. These findings highlight the importance of targeting specific PTSD symptom clusters and corresponding neural pathways in future trauma interventions.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating psychiatric condition that can develop following exposure to traumatic events, such as the loss of a loved one (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In China, a population particularly vulnerable to PTSD are Shidu parents, those who have lost their only child and, having exceeded their reproductive years (with mothers typically over 49 years of age), are unable or unwilling to have or adopt another child (Chen, 2013; Eli et al., 2021). Within the Chinese cultural context, where family lineage is highly valued (Feng, 2018), these parents face profound psychological challenges due to the intersection of personal grief and sociocultural expectations (Eli et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2018). This often leads to complex psychological trauma, with studies reporting PTSD prevalence rates among Shidu parents ranging from 32.6 % to 83.5 % (Eli et al., 2023; Wang & Xu, 2016; Yin et al., 2018). Despite the high prevalence of PTSD in this population, empirically supported interventions tailored to their unique needs remain limited.

While traditional treatments for PTSD, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and exposure therapy, have demonstrated efficacy, they face significant limitations that reduce their suitability for Shidu parents. These approaches are often resource-intensive, requiring specialized therapist training and ongoing one-on-one sessions, which demands significant time commitments from both patients and therapists (Imel et al., 2013). Moreover, they carry the risk of inadvertently retraumatizing individuals, a particular concern for Shidu parents whose trauma is profound and multifaceted. This population endures a constellation of unique psychological and cultural challenges that render their trauma particularly complex and persistent. Psychologically, they suffer not only from profound grief but also a devastating loss of meaning and purpose in life (Wang & Hu, 2019), as a child is often the primary source of hope and meaning for parents in Chinese society (Zimmer & Kwong, 2003). Culturally, children often carry the full weight of familial expectations and the responsibility to continue the family line (Feng, 2018; Wei et al., 2016). The loss of an only child is frequently perceived as a mark of bad luck or personal failure (Zheng & Lawson, 2015), leading to intense stigmatization and social withdrawal (Eli, 2019). This potent combination of existential despair and culturally specific stigma makes many Shidu parents hesitant to engage in traditional, emotionally demanding interventions, a reluctance that contributes to the chronicity of their condition (Eli, 2019; Wang & Hu, 2019). Consequently, there is a critical need to develop alternative interventions that are not only effective but also culturally congruent, less emotionally demanding, and more acceptable to this uniquely vulnerable group.

Cognitive models of PTSD propose that maladaptive attentional biases toward threat-related stimuli play a crucial role in both the maintenance and remission of PTSD symptoms (Bar-Haim et al., 2007). Empirical studies have also found that attentional biases toward threat-related stimuli are positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity, underscoring the importance of addressing these biases in treatment (Eli et al., 2023; Powers et al., 2019). Attention training interventions, such as attention bias modification (ABM) and attention control training (ACT), have shown promise in reducing PTSD symptoms by modifying dysfunctional attentional patterns (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Bar-Haim, 2010). ABM is designed to shift attention away from threats by creating an implicit association between neutral stimuli and the target location (Bar-Haim, 2010; Kuckertz et al., 2014), while ACT uses a balanced task to enhance general attentional control without specifically biasing attention in a particular direction (Badura-Brack et al., 2015). This offers a promising direction for trauma intervention among Shidu parents, as attention training techniques may help alleviate their PTSD symptoms without necessitating direct confrontation with traumatic memories, an approach that could be more culturally acceptable and less distressing for this vulnerable population.

Despite a growing body of research on the effects of ABM and ACT in the treatment of PTSD, the findings have been inconsistent. Some studies indicate that ABM and ACT produce similar effects on PTSD symptoms (Alon et al., 2022; Niles et al., 2020; Schoorl et al., 2013), while others report a greater reduction in symptoms with ABM compared to ACT (Kuckertz et al., 2014; Wald et al., 2016). Conversely, some research demonstrates that ACT may be more effective than ABM (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Lazarov et al., 2019). These discrepancies may arise from the fundamental differences in the nature of these two intervention approaches.

In essence, ABM alleviates symptoms of PTSD by training individuals to avoid trauma-related stimuli, thereby reducing hypervigilance and physiological arousal (Ochsner & Gross, 2005). This approach aligns with Gross’s proactive attention regulation model (Gross, 1998), which emphasizes symptom relief through disengagement from negative stimuli. In contrast, ACT enhances attentional flexibility in the presence of threats (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Kim & Hamann, 2007), potentially improving emotional regulation. The dual-systems model of self-control (Hofmann et al., 2009) suggests that ACT operates through the following two pathways: weakening automatic threat bias (impulsive system) and strengthening top-down attentional control (control system). Despite these established mechanisms, it remains unclear whether ACT’s benefits depend on emotional content or can be generalized to non-emotional contexts, a question with important theoretical and clinical implications for optimizing treatment specificity and transferability. Previous study have called for further investigation into whether attentional control improvements via ACT extend to emotionally neutral settings (e.g., geometric shapes) (Lazarov et al., 2019), which would help clarify the role of emotional engagement in its efficacy. To investigate this mechanism, we developed attention control geometric training (ACG). We hypothesize that both ACT and ACG will outperform ABM by targeting dual-system regulation, thereby providing greater reduction in PTSD symptoms.

In addition to behavioral outcomes, elucidating the neural mechanisms underlying the effects of attention training can provide valuable insights into its therapeutic processes. Neuroimaging studies have shown that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) has been implicated in attentional control and emotional regulation, and its abnormal activity is associated with attentional biases and anxiety-related disorders (Knight et al., 2020; Nejati et al., 2021; Sagliano et al., 2017; Valadez et al., 2022). For example, hypoactivity in the left DLPFC contributes to a reduction in approach-related behaviors, while hyperacivity in the right DLPFC corresponds to heightened vigilance toward threat (Zwanzger et al., 2014). Modulating activity in these regions can enhance attentional control and improve emotional processing (Knight et al., 2020; Madonna et al., 2019; Zwanzger et al., 2014). Previous research have also explored DLPFC activity after ABM in anxious groups and found that the combined approach of applying inhibitory stimulation over the right DLPFC alongside ABM has been shown to not only alleviate anxiety symptoms but also directly modulate emotion processing (Clarke et al., 2014; Sikki et al., 2025). However, the neural changes associated with ABM, ACT, and ACG in the context of PTSD symptoms among Shidu parents remain unknown. Therefore, we conducted a three-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare the efficacies of ABM, ACT, and ACG in reducing PTSD symptoms among Shidu parents. We also aimed to examine the impacts of these interventions on attentional bias and DLPFC activity, with the goal of contributing to the development of more targeted and effective PTSD symptoms treatments for this specific and vulnerable population.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis RCT conformed to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline. The study protocol was approved by the ethics review committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Ethics approval number: H21044). The trial has been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration number: ChiCTR2400093813). The study was conducted at Luohe in Henan Province between July 2022 and January 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and all participants completed the experiment voluntarily.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) bereaved parents who had lost their only child at least one year earlier and had no living children; (2) aged 50–75 years; (3) right-handed, with normal or corrected visual acuity; and (4) no history of neurological or mental illness that could affect the results of the study.

The CONSORT flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1. Sixty-four Shidu parents were randomly assigned to either the ABM (n = 21), ACT (n = 21), or ACG (n = 22) group. Two participants (ACT =1, ACG = 1) withdrew after completing the first intervention session, whereas the remaining 62 participants (Mage = 62.11, SD = 6.49; Range = 50–75 years old; 22 males) completed all the intervention sessions and tests. The demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1. The groups did not differ in terms of the demographic information and all baseline variables (pall > 0.05).

Demographic information of participants.

Note:aThere are missing values in sociodemographic characteristic, thus, the sum of the effective percentage is note equal to 100 % in these cases; b: Variable information at the base time (T1); Unnatural cause: accident, homicide, suicide, natural disaster, or other; Natural cause: illness. ABM: Attention bias modification; ACT: Attention control training; ACG: Attention control geometric training.

The training protocol involved eight biweekly, face-based dot‒probe sessions (Fig. 2B) and consisted of 256 trials per session. In the ABM condition, the target appeared at the neutral face location in 90 % of the negative–neutral trials. Thus, ABM variants introduced a contingency between the target location and face valence. In the ACT condition, the targets appeared with equal probability at the neutral and negative face locations. The negative face location, probe location, and probe type were fully counterbalanced, with no contingency between face valence and probe location. The ACG condition was the same as the ACT condition with one exception, geometric stimuli were used because ACG involves a nonemotional, nonthreatening context.

ProcedureParticipants who satisfied the inclusion criteria were invited to visit the community office to answer the questionnaire and complete the dot‒probe fNIRS task and treatment. The study design was a parallel-group RCT with three groups and four assessment points. The participants were automatically and randomly assigned to a treatment condition (ABM, ACT, or ACG) in a 1:1:1 ratio, stratified by age, sex, and time since the loss of the child, by using the random case allocation function of the SPSS software. This allocation was maintained throughout the study. The participants completed the assigned program twice per week for 1 month (8 sessions). The participants completed the assessments, including the symptoms and the dot-probe fNIRS task at baseline (pre-treatment: T1), after they completed 3 sessions (mid-treatment: T2), and after they completed all 8 sessions (post-treatment: T3). The follow-up assessment took place four months after the last treatment session (four-month follow-up: T4) and included the symptoms and the dot-probe task without fNIRS.

MeasuresTreatment outcome measuresThe primary outcomes included scores from four subscales of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), namely, intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity, as well as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Trait Version (STAI-T). The secondary outcomes comprised the total scores of the PCL-5 and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-10 (CES-d-10). This division of primary and secondary outcomes was based on previous research (Niles et al., 2020) and the study’s aim: to examine the specific effects of the intervention on distinct symptom of PTSD and anxiety, identified as the key constructs in the study’s theoretical framework. In contrast, the total PCL-5 and CES-d-10 scores were designated as secondary outcomes to explore broader mental health correlates of the intervention.

PCL-5. The PCL-5 is a 20-item, 5-point self-report inventory that assesses the severity of PTSD symptoms experienced within the past week (Weathers et al., 2013). The PCL-5 comprises four subscales, namely, intrusion (Cluster B), avoidance (Cluster C), negative alterations in cognition and mood (Cluster D), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (Cluster E). In the present study, Cronbach’s αs for the total severity score were 0.95, 0.96, 0.97, and 0.97 at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and a follow-up, respectively.

STAI-T. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Trait Version STAI-T comprises 20 items that evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms. Participants rate the frequency of experiencing each item on a 4-point Likert scale (Spielberger, 1985). In the present study, Cronbach’s αs for the total severity score were 0.90, 0.86, 0.86, and 0.90 at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and a follow-up, respectively.

CES-d-10. The CES-d-10 consists of 10 items that assess the severity of depression (Andresen et al., 1994). Participants indicate the extent to which each symptom has bothered them during the past week by using a 4-point Likert scale. In the present study, Cronbach’s αs for the total severity score were 0.88, 0.83, 0.86, and 0.88 at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and a follow-up, respectively.

Treatment mechanism measuresWe examined changes in attentional bias and DLPFC activity as underlying mechanisms.

Attentional bias. Attentional bias was measured via a face-based, event-related dot-probe fNIRS task in E-Prime 2.0. In the dot-probe task (Fig. 2A), each trial began with the presentation of a white fixation cross for 500 ms at the center of a black screen; subsequently, a pair of faces were presented on either side of the fixation cross for a stimulus presentation duration of 750 ms; in each pair, a negative or neutral face was randomly paired with a neutral face. Immediately following the offset of the face pair, a probe took the place of one of the faces; the probe remained present until the participants pressed a button or 3000 ms had passed; the next trial started after 1000 ms. Each participant performed a total of 140 trials, and all trials appeared in random order. The participants were presented with an equal number of trials counterbalanced according to face pair, emotional valence, face location, probe type, and probe location across participants such that each face appeared in either location with equal probability.

Three conditions, namely, “congruent”, “incongruent”, and “neutral”, were tested. In congruent trials, the probe appeared on the same side as the negative faces. In incongruent trials, the probe appeared on the same side as the neutral faces. For the negative face pairs, half were congruent, and the other half were incongruent. In the neutral trials, two neutral faces were displayed, and the probe was displayed randomly on one side.

The attentional bias index was calculated as the difference between the average RT to targets in emotional and neutral image locations. Vigilance was calculated as RTneutral − RTcongruent; Positive values (faster orientation towards negative stimuli) indicate vigilance toward negative stimuli, negative values (slower orientation towards negative stimuli) indicate avoidance, and zero indicates no bias. Disengagement was calculated as RTincongruent − RTneutral; Positive values (slower disengagement from negative stimuli) represent difficulty disengaging from negative stimuli and negative values representing faster disengagement from negative stimuli (Evans et al., 2016; Salemink et al., 2007).

The facial stimuli, including 44 negative emotional images (anger, fear, and sadness; half male and half female) and 108 neutral images (calm; half male and half female), were selected from the Chinese Affective Face Picture System (CAFPS). Photoshop software was used to standardize and create uniformly sized images.

DLPFC activity. A Shimadzu LABNIRS near-infrared optical imager was used to monitor changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO), deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR), and total hemoglobin (HbT) concentrations in the PFC via three wavelengths of near-infrared semiconductor lasers (780 nm, 805 nm, and 830 nm). The sampling rate was set at 13.33 Hz. A total of 8 transmitting fibers and 8 receiving fibers were employed, resulting in 20 channels that covered the PFC. The distance between each transmitting fiber and its corresponding receiving fiber was 30 mm.

Using the 3D positioning device FASTRAK, we recorded the four reference points (Nz, Cz, AL, AR) of the EEG 10/20 system to obtain the three-dimensional coordinate information for all the probes. NIR_SPM was subsequently used to convert these coordinates into 20-channel MNI coordinates and to estimate the likelihood of each channel's distribution area (Ye et al., 2009). The specific distributions of the brain measurement areas and the 20 channels in the PFC are presented in Table S1. On the basis of previous studies, the regions of interest (ROIs) in this study focused on the DLPFC (Ahmadizadeh et al., 2019; Knight et al., 2020; Nejati et al., 2021).

The fNIRS data were obtained via the NIRS-KIT software running on MATLAB (Hou et al., 2021). The first step involved preprocessing the data. The Temporary Derivative Distribution Repair (TDDR) algorithm was used to remove motion artifacts, and the Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) method with a bandpass filter of 0.01∼0.08 Hz was used to remove noise and drift. The second step involved conducting individual-level analysis. By using the general linear model (GLM) for parameter estimation, the relevant β values of each participant under different task conditions, which were used as physiological indicators to measure the activation of corresponding brain regions, were obtained. The third step involved conducting a group-level analysis.

Statistical analysesThe questionnaire and behavioral data were analyzed via SPSS 21.0 statistical software. Before attention bias indicators were calculated, trials with reaction times (RTs) <300 ms or >2000 ms were excluded from the analysis. To explore group differences in baseline descriptive statistics, repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and χ2 tests were computed. Treatment effects were tested via generalized estimating equations (GEEs), as recommended for RCTs (Zeger et al., 1988). The GEE models tested time (T1, T2, T3, and T4) by group (ABM, ACT, and ACG) effects on symptoms and attentional bias measures. The main effects of time and group, and their interaction effects were estimated. To investigate the longitudinal changes in DLPFC activity, we performed paired-sample t-tests comparing activation levels between T1 (pre-treatment), T2 (mid-treatment), and T3 (post-treatment). These analyses were conducted separately for the vigilance and disengagement conditions to identify changes specific to each attentional bias component. The false discovery rate (FDR) was used to correct all p values between channels. After correction, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsTreatment adherenceAmong the 64 participants, 62 (96.9 %) completed all 8 sessions: 100 % in the ABM group, 95.2 % in the ACT group, and 95.5 % in the ACG group. The remaining 2 (3.1 %) participants completed only 1 session before they requested to withdraw from treatment.

Changes in symptoms and attentional biasBefore presenting the detailed GEE statistics, the key findings for symptoms and attentional bias are summarized in Table 2. The primary results indicate that the ACT was associated with significant improvements in intrusion symptoms and vigilance towards threat. Other symptoms and attentional disengagement showed changes over time but did not differ specifically between the treatment groups.

Summary of key findings from GEE analysis of symptoms and attentional bias.

Specifically, the results of the GEE model for symptoms are shown in Fig. 3A. GEE analyses revealed a significant time-by-group interaction for intrusion scores (Wald χ2 = 13.08, p < 0.05). The main effect of time was also significant (Wald χ2 = 10.78, p < 0.05), while the main effect of group was not (p > 0.05). This significant interaction indicates that the trajectory of intrusion symptoms over time differed significantly among the groups. Post-hoc simple effect analyses confirmed that this interaction was driven by the ACT group: intrusion symptoms showed significant and sustained decreases from T1 to T2 (d = 1.75, p < 0.05), T1 to T4 (d = 2.23, p < 0.05), and T3 to T4 (d = 2.53, p < 0.05). In contrast, the ABM and ACG groups showed no significant changes in intrusion scores across all time points (pall > 0.05). GEE analyses of negative alterations in the cognition and mood scores revealed a main effect of time (Wald χ2 = 13.66, p < 0.01); symptoms increased from T2 to T3 (d = −1.57, p < 0.01) and decreased from T3 to T4 (d = 1.77, p < 0.01).The main effects of group and time-by-group interactions were nonsignificant (pall > 0.05). This fluctuation represented a transient pattern and no intervention group demonstrated a specific advantage in alleviating this symptom cluster. GEE analyses of avoidance, alterations in arousal and reactivity, PTSD total, anxiety, and depression scores revealed that the main effects of time, group, and time-by-group interactions were nonsignificant (pall > 0.05), indicating that they did not significantly change with treatment.

GEE analyses of the attentional bias index are shown in Fig. 3B. For vigilance scores, GEE analyses yielded a significant time-by-group interaction (Wald χ2 = 16.23, p < 0.05). The main effect of time was also significant (Wald χ2 = 10.75, p < 0.05), while the main effect of group was not (p > 0.05). Post-hoc simple effect analyses revealed distinct patterns across groups: the ACT group demonstrated significant and sustained reduction in vigilance toward threat from T1 to T2 (d = 20.47, p < 0.05), T1 to T3 (d = 15.85, p < 0.05), and T1 to T4 (d = 34.52, p < 0.05), whereas the ACG group showed a non-significant downward trend from T1 to T4 (d = 24.74, p = 0.062) and from T3 to T4 (d = 20.91, p = 0.067). The ABM group, in contrast, exhibited no significant changes over time (all p > 0.05). The disengagement scores revealed a main effect of time (Wald χ2 = 16.24, p < 0.01); faster disengagement from threat decreased from T1 to T2 (d = −26.33, p < 0.001), from T1 to T3 (d = −23.12, p < 0.05), and from T1 to T4 (d = −20.64, p < 0.01). The main effects of group and time-by-group interactions were nonsignificant (pall > 0.05).

Changes in dlpfc activityThe paired sample t tests results are shown in Figs. 4A, B and 5A, B. For comparison of the DLPFC activity over time, see Table S2.

ABM group. Under vigilance and disengagement conditions, DLPFC activity did not significantly change over time (pall > 0.05).

ACT group. Under the vigilance condition, the results revealed a significant decrease in the left DLPFC (CH5: tT1 v. T2 = 2.71, p < 0.05) and right DLPFC (CH15: tT1 v. T2 = 2.93, CH16: tT1 v. T2 = 3.17, CH18: tT1 v. T3 = 2.68, CH19: tT1 v. T3 = 2.27, pall < 0.05) over time. Under the disengagement condition, the results revealed a significant increase in the left DLPFC (CH5: tT1 v. T3 = −2.28, p < 0.05) and right DLPFC (CH15: tT1 v. T2 = −1.92, tT1 v. T3 = −2.07, CH17: tT1 v. T3 = −2.42, pall < 0.05) over time.

ACG group. Under the vigilance condition, the results revealed a significant decrease in the left DLPFC (CH5: tT1 v. T3 = 2.34, p < 0.05) over time. Under the disengagement condition, the results revealed a significant increase in the left DLPFC (CH5: tT1 v. T3 = −2.28, CH8: tT1 v. T3 = −1.89, tT2 v. T3 = −2.08, CH9: tT1 v. T3 = −2.30, pall < 0.05) and right DLPFC (CH16: tT1 v. T2 = −2.71, CH17: tT1 v. T3 = −2.71, tT2 v. T3 = −2.70, pall < 0.05) over time.

DiscussionThe present study evaluated the efficacy of three distinct interventions, ABM, ACT, and ACG, in alleviating PTSD symptoms among Shidu parents, using a multimodal assessment of behavioral and neural outcomes. The key findings revealed a coherent pattern of improvement specifically for the ACT group, with significant reductions in intrusion symptoms of PTSD maintained at the four-month follow-up. At the neurocognitive level, ACT showed decreased vigilance toward threat, accompanied by decreased bilateral DLPFC activation. In contrast, although ACG showed a nonsignificant trend toward decreased vigilance to threat, accompanied by reduced activity in the left DLPFC under vigilance condition, these changes did not lead to significant symptom relief, indicating a dissociation between neurocognitive and clinical outcomes. Conversely, ABM showed no significant improvements in either behavioral or neural measures.

As we expected, the present study demonstrated that ACT was more effective than ABM in alleviating PTSD symptoms, particularly intrusive symptoms. This finding aligns with previous research (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Lazarov et al., 2019) and extends their conclusions to the population of Shidu parents. The superior efficacy of ACT may be attributed to its dual focus on enhancing attentional control and fostering adaptive emotional regulation (Hakamata et al., 2018; Hofmann et al., 2009; Kim & Hamann, 2007). In contrast, ABM’s narrow emphasis on threat avoidance (Ochsner & Gross, 2005) appears insufficient to address the multifaceted nature of PTSD, especially in high-trauma populations such as Shidu parents, who experience profound grief and unique cultural stigma (Zheng & Lawson, 2015). Unlike ACT, which enhances attentional flexibility, ABM’s mechanism, simply redirecting attention away from threats, does not adequately meet the complex needs of this group, particularly given their marked impairments in attentional control and emotional regulation (Aupperle et al., 2012; Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Eli et al., 2023). Thus, while ABM has shown efficacy in military populations (Kuckertz et al., 2014; Wald et al., 2016), our results revealed no significant treatment effects of ABM across all measured outcomes. This highlights critical population differences and suggests that standardized attention modification protocols may require adaptation for different trauma populations.

Furthermore, our findings indicate that ACT’s efficacy was primarily demonstrated in alleviating intrusion symptoms, while other PTSD symptom clusters, as well as anxiety and depression did not show significant improvement. This pattern of specific efficacy, we argue, stems from the precise alignment between ACT's mechanistic target and the nature of intrusion symptoms, contrasted with the more complex etiology of other symptoms—a distinction that is particularly salient in our sample of Shidu parents. Intrusion symptoms are largely driven by automatic, bottom-up hypervigilance for threat (Hayes et al., 2012), a process that ACT is specifically designed to address by strengthening top-down attentional control (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Hofmann et al., 2009). However, in this population, symptoms of negative alterations in cognition and mood (e.g., pervasive guilt, feelings of meaninglessness), alterations in arousal and reactivity (e.g., irritability/anger), and avoidance (of reminders of the child and of social contexts) are not merely PTSD symptoms but are deeply woven into the fabric of their new identity and social existence (Eli, 2019; Eli et al., 2021; Wang & Hu, 2019). The loss of an only child in the Chinese cultural context carries specific socio-cultural pressures, such as the rupture of the family line and future security (Feng, 2018; Wei et al., 2016), which can solidify depressive and anxious worldviews. These broader symptoms are sustained by overlearned cognitive appraisals and meaning-based struggles that extend beyond the scope of a targeted attention training regimen (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Thus, while ACT effectively mitigates the automatic attentional processes underlying intrusions, the intervention's focused nature and the profound complexity of the grief trauma likely account for its limited effects on the wider symptomatology.

The integration of behavioral and neuroimaging data in this study reveals a compelling dissociation between specific therapeutic efficacy and non-specific neurocognitive engagement, primarily elucidated by comparing the ACT and ACG groups. Our key finding is that ACT produced a specific and coherent pattern of improvement. The baseline hyperactivation of the DLPFC during vigilance to threat may reflect excessive and inefficient cognitive effort to monitor potential threats (Liu et al., 2006), a hallmark of hyperarousal in PTSD (Hayes et al., 2012). ACT significantly reduced behavioral vigilance towards threat, which was may underpinned by a decrease in bilateral DLPFC activation under the vigilance condition (Clarke et al., 2014; Sikki et al., 2025). This pattern strongly suggests a normalization of hypervigilance, where less top-down cognitive effort from the DLPFC is required to maintain a non-vigilant state, indicating enhanced neural efficiency (Hofmann et al., 2009). This behavioral-neural coupling is a hallmark of a targeted intervention effectively mitigating a core pathological process in PTSD symptoms.

Conversely, the ACG group presents a more nuanced picture that highlights the distinction between neural change and clinical recovery. While the ACG demonstrated a significant reduction in left DLPFC activity under the vigilance condition, this neural change was both spatially limited and functionally decoupled from behavior, as it corresponded to only a non-significant trend in reduced vigilance toward threat. In contrast to the bilateral, behaviorally-coupled DLPFC modulation seen in the ACT group—reflecting comprehensive engagement of cognitive control networks—the ACG's unilateral change suggests an incomplete recalibration of the threat monitoring system. Such limited engagement likely failed to reach the critical threshold necessary to reorganize the maladaptive attentional processes underlying PTSD symptomatology, underscoring that therapeutic efficacy requires not just neural change, but coordinated, network-level normalization (Cramer et al., 2011).

The dissociation observed in the ACG group underscores a critical theoretical and clinical question: what is necessary to translate neural change into clinical recovery? This dissociation observed in the ACG also underscores the necessity of an emotion-integrated approach for achieving full therapeutic impact. According to emotional processing theory, effective PTSD treatment requires not only improved cognitive control but also the activation and modification of the fear memory structures underlying the disorder (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Rauch & Foa, 2006). The supportive yet emotionally neutral context of ACG may fail to adequately engage and restructure these emotional networks. Consequently, enhancing attentional control may be necessary but not sufficient for symptom reduction. The comprehensive efficacy of ACT likely stems from its dual action: it simultaneously enhances top-down control and promotes a more adaptive, less reactive relationship with internal experiences (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Hofmann et al., 2009; Kim & Hamann, 2007), thereby directly mitigating the intrusive symptoms.

Beyond the dissociations between groups, a general pattern was observed across all groups for attentional disengagement: the speed of disengagement from threat significantly decreased over time, suggesting a non-specific effect of participation. This behavioral shift points to more elaborated cognitive processing of threat stimuli instead of reflexive avoidance, indicating a positive reduction in automatic avoidance and a move toward improved emotional regulation (Cisler & Koster, 2010). The fNIRS data further substantiate this interpretation, showing enhanced bilateral DLPFC activation under the disengagement condition in both the ACT and ACG groups. As the DLPFC is central to top-down cognitive control (Sagliano et al., 2017), its heightened engagement reflects the active recruitment of cognitive resources for controlled, deliberate disengagement rather than impulsive reaction (Nejati et al., 2021; Sagliano et al., 2017). This convergence of behavioral and neural evidence supports a shared mechanism across both interventions: strengthened top-down cognitive control via DLPFC engagement (Aupperle et al., 2012). Future studies should validate this finding across diverse populations and explore its longitudinal development.

Certain study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small due to difficulties in accessing this bereaved population, which limited the ability to detect smaller intervention effects between pre- and post-treatment measures as well as at follow-up. Future research should aim to replicate these findings with larger samples. Second, although the fNIRS indicators showed significant changes over time, data at the four-month follow-up were unavailable due to practical constraints during that period. Addressing this gap in future studies is necessary. Third, PTSD symptoms were assessed using a self-report questionnaire rather than a clinical interview. Future research should incorporate structured clinical assessments to validate these findings. Finally, although the attentional bias index was derived from participants' reaction times in a behavioral task, a well-established and reliable method for assessing attentional bias (Cisler & Koster, 2010; Schäfer et al., 2016), future studies should consider integrating eye-tracking technology to enhance methodological approaches. This would capture attentional processes at a different level of analysis (i.e., direct gaze behavior), thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding.

ConclusionIn summary, this randomized controlled trial demonstrates that ACT is a promising intervention for alleviating intrusion symptoms and vigilance to threat in Shidu parents, potentially through the normalization of bilateral DLPFC hyperactivity. In contrast, ABM showed no significant effects, while the neurocognitive changes elicited by non-emotional ACG were insufficient for clinical recovery. These findings underscore the importance of emotion-integrated, mechanism-targeted interventions and highlight that enhanced top-down cognitive control, although a shared neurocognitive pathway, may be a necessary but not sufficient condition for meaningful symptom reduction in this uniquely traumatized population.

FundingThis work was supported by the Tianchi Talent Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2024, Buzohre Eli); the Shihezi University High level Talent Research Launch Project (RCSK202435); the Shihezi University self-funded support for university-level research projects (ZZZC2023076); National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3605304); and the Bingtuan Guiding Plan Project (2024ZD034).

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We extend our sincere gratitude to all participants and organizations that supported this research.