Edited by: Dr. Juan Carlos Sierra (University of Granada, Granada, Spain)

Dr. Nieves Moyano (University of Jaen, Jaen, Spain)

Last update: May 2025

More infoThe Sexual Abuse History Questionnaire (SAHQ), a widely used screening tool for childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and adolescent/adult sexual assault (AASA) experiences, has limited examination of its psychometric properties in diverse populations. Our study assessed the SAHQ's psychometric properties (i.e., structural validity and measurement invariance across demographic groups, know-group validity, and internal consistency) and estimated the frequencies of various types of sexual victimization across 42 countries and in diverse gender-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups that were previously missing from measurement-focused studies. We used a large, non-representative sample (N = 81,465; 57 % women, 3.4 % gender-diverse individuals, Mage=32.34 years, SD=12.48) from the International Sex Survey, a 42-country cross-sectional, multi-language, online survey. The SAHQ demonstrated excellent structural validity in all country-, gender-, sexual-identity-, and trans-status-based groups, as well as acceptable reliability and known-group validity. Occurrence estimates for six CSA and AASA types were reported across sociodemographic groups, corroborating previous evidence that women and gender- and sexual-minority individuals are at greater risk of CSA and AASA. Pansexual and queer individuals emerged as a particularly vulnerable group. Associations between different types of CSA and AASA revealed that participants who experienced any form of CSA were at least twice as likely to experience AASA. The findings have significant implications for policy and interventions, especially for marginalized groups.

Sexual violence is present across different cultures, age groups, sexual identities, and gender identities, with a high lifetime prevalence in the general population, especially among women and sexual and gender minorities (Dworkin et al., 2021; Rothman et al., 2011; Sterzing et al., 2017; Walters et al., 2013; WHO, 2021). Considering the overarching effects of sexual violence on almost all areas of well-being and function, and the high risk of revictimization (Walker et al., 2019), screening for a variety of unwanted sexual experiences is important for research, epidemiologic, and clinical purposes. However, few scales assess both childhood and later-in-life sexual victimization, and thus revictimization. Even fewer of such scales have been validated across different languages, countries, and a diverse group of gender and sexual identities, and most published data are from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) countries. To address these gaps, the present study examined the psychometric properties of the Sexual Abuse History Questionnaire (SAHQ; Leserman et al., 1995) and estimate the occurrence rates of childhood, adolescent, and adult unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., unwanted touching of sexual organs) across 42 countries and in a variety of sexual and gender-diverse groups that were previously missing from measurement-focused studies.

Definitions and outcomes of adult/adolescent sexual assault and child sexual abuseSexual violence, which includes but is not limited to child, adolescent, and adult unwanted sexual experiences, is defined as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic or otherwise directed against a person's sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work (Krug et al., 2002). Specifically, child sexual abuse is defined as the involvement of a child in sexual activity that they do not fully comprehend and to which a child is unable to give informed consent, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared, or violates the laws or social taboos of society (WHO, 1999). Sexual violence towards adults, adolescents (such as adolescent/adult sexual assault,AASA), and children (such as child sexual abuse, [CSA]) is a complex and diverse phenomenon, involving a spectrum of experiences from unambiguously unwanted sexual experiences to forms of violence where the victims’ compliance is obtained via manipulation, emotional coercion, deception, or abuse of power (Kelly, 1987). The instrument examined in this study assesses six types of unwanted sexual experiences (i.e., someone exposing their sexual organs, threatening with rape, touching one's sexual organs non-consensually, being forced to touch someone's sexual organs, being forced to have intercourse, and “any other unwanted sexual experiences”) in two developmental stages (childhood and adolescence/adulthood) (Leserman et al., 1995).

Broadly speaking, AASA has been associated with numerous negative mental, physical, and social outcomes that may include several psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use disorders (Dworkin, 2020; Dworkin et al., 2017), sexual dysfunctions (Steel & Herlitz, 2007), and suicidal thoughts and behavior (Dworkin et al., 2022). CSA has been associated with depression, anxiety disorders (Amado et al., 2015; Maniglio, 2010), post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, suicide attempts and ideation (L. P. Chen et al., 2010), borderline personality disorder (de Aquino Ferreira et al., 2018), sexual compulsivity (Slavin, Scoglio et al., 2020), lower sexual functioning (Gewirtz-Meydan & Opuda, 2022; Pulverman et al., 2018), insecure attachment styles (Labadie et al., 2018), and lower educational level (de Jong et al., 2015). In addition, individuals who experienced CSA are also more likely to encounter unwanted sexual experiences later in life (Walker et al., 2019).

Cross-cultural prevalence of AASA and CSAThe cross-cultural prevalence of both CSA and AASA vary highly in the literature as methodological differences (e.g., the definition of sexual abuse or assault, acts included, the choice of age cut-off), and the relatively low number of studies from non-WEIRD countries hinder advances in this area (Dunne et al., 2009). According to a systematic review summarizing data outside of North America, the lifetime prevalence of AASA ranged between 0.3–55.8 % in Europe, 0–51.9 % in Latin America, 0.6–77.6 % in Asia, and 15–16.5 % in Africa, with women generally reporting higher rates of victimization than men (Dworkin et al., 2021).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that 15–35 % of girls and 5–20 % of boys have experienced CSA worldwide (Andersson et al., 2020; Barth et al., 2013; Finkelhor et al., 2015; Kloppen et al., 2016; Ma, 2018; Pereda et al., 2009; Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). These wide ranges of estimates may be affected by the age cut-off and the type of abuse studied, with generally higher rates for non-contact CSA than contact CSA (i.e., sexual abuse involving vs. not involving physical contact). Importantly, some authors note that the lower rates of men disclosing sexual victimization, especially CSA, may partially be due to underreporting (Pereda et al., 2009).

Prevalence of AASA and CSA across Gender- and Sexual minoritiesResearch including gender minority (specifically, transgender, non-binary or other gender-diverse individuals) and sexual minority participants (specifically, lesbian, gay, bisexual or other non-heterosexual identities) suggests that they report higher rates of both childhood and later-in-life sexual victimization compared to cisgender and heterosexual individuals, suggesting an important health disparity (Canan et al., 2021; Dworkin et al., 2021; Friedman et al., 2011; Rothman et al., 2011). A systematic review of sexual- and gender-minority samples from four continents revealed a wide range of self-reported assault prevalence estimates. Past-year victimization ranged between 14.8 to 38.3 % in Africa, 17.5 % in Asia, 2 to 3 % in Europe, and 1.5 to 54.1 % in Latin America (Dworkin et al., 2021). A systematic review of 75 US studies observed estimates ranging between 11.3–53.2 % for women and 10.1–44.7 % for men who identify as gay or lesbian (Rothman et al., 2011). Another epidemiological study estimated even higher prevalence in groups of sexual minority women, with 63 % of lesbian and 80 % of bisexual women reporting some form of sexual assault compared to 44 % of heterosexual women (Canan et al., 2021). While it seems bisexual individuals are at a higher risk of experiencing various forms of AASA than those who identify as gay or lesbian, available data show that other plurisexual individuals (e.g., pansexual, queer) may be even more vulnerable than their bisexual peers (Flanders et al., 2019).

Compared to heterosexual individuals, sexual-minority individuals in Canadian and US samples reported experiencing CSA 2.5–5.7 times more often (Baams, 2018; Friedman et al., 2011). Regarding gender-minority status, transgender adolescents are 2–4.4 times more likely to experience CSA compared to their cisgender counterparts (Baams, 2018; Thoma et al., 2021). Considering the intersections of gender- and sexual-minority status, transgender and gender-non-conforming youth may be at even higher risk for CSA than cisgender sexual-minority individuals (Sterzing et al., 2017; Tobin & Delaney, 2019).

Implications for measurementThese findings underscore the importance of re-examining the psychometric properties of sexual victimization measures with the inclusion of gender- and sexual-minority groups and adopting a more nuanced approach to represent diverse individuals. This could involve the inclusion of underrepresented emerging sexual identities such as pansexual, hetero- and homoflexible, or asexual individuals. Previously, smaller sample sizes posed challenges in exploring less prevalent sexual identities due to low representation within general population samples (Borgogna et al., 2019). The traditional approach of compiling these distinct groups into a general sexual-minority category or omitting them from comparative and psychometric studies may render an incomplete picture. The availability of psychometrically sound, brief but sensitive screening for sexual victimization experiences in survey studies is important for identifying and understanding the prevalence of sexual victimization, and consequently, to address its pervasive impact on individuals and communities. To address this gap, we examined the psychometric properties of the Sexual Abuse History Questionnaire (SAHQ; Leserman et al., 1995) in a large cross-cultural sample that includes respondents from non-WEIRD countries, as well as a variety of sexual and gender minorities.

The sexual abuse history questionnaire (SAHQ)The SAHQ is a concise, easy-to-read, low-burden screening tool that retrospectively measures a set of unwanted sexual experiences during childhood (13 years or younger; CSA scale) and adolescent/adult years (14 years or older; AASA scale). Historically, the SAHQ has been used in both clinical and general population settings, regardless of individuals’ gender identity or sexual orientation (e.g., Estlein et al., 2024; Leserman et al., 1995; Slavin et al., 2020). Five items ask about five specific forms of sexual victimization (i.e., someone exposing their sexual organs to the victim, threatening with rape, touching one's sexual organs, being forced to touch someone's sexual organs, and being forced to have intercourse) and one item assesses “any other unwanted sexual experiences.” The measure asks the same questions twice, first regarding childhood, then adolescent and adult years. Respondents indicate if a given type of victimization happened to them in childhood and/or later in life by providing a yes or no answer on both scales separately. For the wording of the instructions and items in English, see Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials.

Although there is some evidence that individuals who experienced multiple types of sexual violence (i.e., contact and non-contact) report more detrimental mental health outcomes than survivors of exclusively contact or non-contact sexual abuse (e.g., Landolt et al., 2016), we sought to validate the SAHQ as a screening tool that is used to detect a range of unwanted sexual experiences. Following previous conventions (e.g., Chiang et al., 2016; Dunne et al., 2009; Hamby et al., 2004), no total score was calculated for the dichotomous questions on either scale, with the consideration that a higher score may not equate with more severe trauma and that we cannot know if saying yes to multiple items refers to separate experiences of victimization or aspects of the same experience. Instead, we reported and compared occurrences of different CSA and AASA experiences separately. However, we acknowledge that previous studies have scored and interpreted the SAHQ diversely, with some using a composite score to create categorical variables (i.e., victimized/ not victimized; e.g., Grossi et al., 2018; Slavin et al., 2020; Toomey et al., 1993), some calculating a sum score of the number of yes answers (e.g., Estlein et al., 2024), and some proposing a weighted aggregate scoring method for a modified version of the SAHQ (Godbout et al., 2019; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015). This inconsistency warrants further examination.

Characteristics and appropriate use of the SAHQThe SAHQ is a short measure that can be useful for the rapid screening of sexual victimization in two developmental stages. In comparison to other widely-used multi-lingual self-report measures assessing sexual victimization (e.g., the VACS, ICAST-R, and JVQ, Chiang et al., 2016; Dunne et al., 2009; Hamby et al., 2004), its main contribution is the simultaneous assessment of CSA and AASA experiences and its ability to detect revictimization (i.e., victimization both as a child and as an adolescent/adult). Like most instruments, the SAHQ has advantages and limitations that should be considered when choosing the most appropriate survey measure.

Assessing different types of sexually violent acts provides more nuanced information on how victimization may occur and may help individuals to label, recall and thus report experiences of sexual victimization more accurately (United Nations, 2014). Nevertheless, the SAHQ does not address all important aspects of victimization (e.g., frequency, perpetrator, disclosure, etc.), and does not cover all forms of sexual violence that constitute CSA (where the definition does not involve consent) or AASA. Although unwanted sexual experiences are present in childhood (e.g., implied by the relatively high ratios of peer-perpetrated sexual violence), and calls have been made by scholars to recognize the complexity of unwanted sexual experiences at this age (Gewirtz-Meydan & Finkelhor, 2020), it is important to note that the WHO definition (1999) of CSA does not involve the lack of consent as a criterion. The language used in the SAHQ (“when you did not want it”) may not be sensitive enough to detect survivors who do not recognize or label their CSA experiences as unwanted, even retrospectively.

The SAHQ uses a standard age cutoff of 14 years old to distinguish between CSA and AASA experiences. The standard age-cutoff is important for comparative cross-population research, but notably, does not align with the legally defined age of consent in all jurisdictions. As there is no clear-cut empirical evidence to indicate which age is the best cutoff point to distinguish between the developmental stages in which trauma may be experienced, the authors of the SAHQ chose a commonly used age cutoff (Leserman et al., 1995). Supporting this cutoff, a recent large, nationally representative U.S. study's findings suggest that sexual violence perpetrated by peers (as opposed to adults) becomes the predominant form of victimization around this time (Gewirtz-Meydan & Finkelhor, 2020).

The SAHQ may be best used in research aiming to identify the form of victimization, revictimization research, cross-cultural comparative studies, and studies comparing the potential effects of certain types of victimization at different developmental stages. Its brief format is advantageous in long survey batteries, for populations with shorter attention spans, when aiming to minimize the emotional burden brought on by questions about unwanted sexual experiences (often a requirement from ethical boards), or in populations in which higher-than-usual participant distress may be expected from such inquiry (as opposed to more comprehensive interviews that provide more detail but may cause higher participant distress). In appropriate settings, it may be used as a brief, low-burden screening instrument before a more thorough follow-up interview.

Aims and hypothesesIn this study, we examined the psychometric properties of the SAHQ and estimated the occurrence of various types of sexual victimization across different countries, gender, and sexual identities, including often underrepresented non-WEIRD countries, and gender and sexual minorities. First, we examined the CSA and AASA scales’ factor structure in country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups to test whether their dimensionality was similar across populations. Second, we assessed the reliability, as well as known-group validity with empirically relevant constructs (i.e., depression and anxiety, which have a robust and well-documented association with CSA and AASA in previous studies, see Amado et al., 2015; Dworkin, 2020; Maniglio, 2010). Then, we reported and compared occurrence estimates of six types of CSA and AASA experiences across the gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups.1 Based on previous studies (Baams, 2018; Flanders et al., 2019; Friedman et al., 2011; Rothman et al., 2011; Thoma et al., 2021; Walters et al., 2013), we expected that (a) participants who identified as women or gender-diverse (e.g., non-binary, genderqueer)2 would report more CSA and AASA than participants who identified as men, (b) transgender participants would report more CSA and AASA than cisgender individuals, and (c) sexual-minority individuals, especially plurisexual (e.g., bisexual, pansexual) individuals, would report more CSA and AASA than heterosexual individuals. Lastly, we examined the associations between different types of CSA and AASA experiences. As the literature indicates that survivors of CSA appear at greater risk of unwanted sexual experiences later in their life (Walker et al., 2019), we expected to observe a significant positive association in our sample as well.

MethodProcedureThe International Sex Survey (ISS, https://www.internationalsexsurvey.org/), a 42-country3 cross-sectional, multi-language, self-report survey provided the data for this study (for detailed study protocol see Bőthe et al. (2021), preregistered study design: https://osf.io/uyfra, list of publications: https://osf.io/jb6ey). The study was conducted in 26 languages. The English survey battery was translated by the study's native-speaking collaborating researchers following a pre-established translation protocol (Beaton et al., 2000).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All collaborating countries’ national/institutional ethics review boards approved the study or considered the study exempt as it had already been approved by the ethics committees of the principal investigators’ institutions: https://osf.io/n3k2c. The study sample was collected between October 2021 and May 2022 via news media appearances, research panels, and social media ads with the help of standard multi-lingual advertisement material created by the core research team and distributed by the collaborators in each participating country (e.g., templates of emails and articles to contact news websites, study advertisement text, and study advertisement posters).4 The advertisement materials explicitly stated that participation in the study is completely anonymous, and anyone meeting the eligibility criteria can participate in the study, promoting inclusivity and encouraging participants to share sensitive information. Participants who provided informed consent completed a self-report, anonymous survey on a secure online platform (Qualtrics Research Suite), taking approximately 25 to 45 min. As an incentive, all participants were informed that at the end of the survey they could choose to donate 50 US cents to a global sexual health organization, up to 1000 USD of donation.

ParticipantsParticipants had to be at least 18 years old (or the legal age to provide informed consent) and understand any of the survey languages. Participants who gave incorrect answers to at least two attention-testing questions out of three and/or produced unengaged response patterns (e.g., giving the same response to all items in questionnaires with reverse-coded items, indicating a longer romantic relationship than their age, etc.) were excluded from the final dataset. For a detailed description of the data-cleaning procedure, see https://osf.io/8kdzv/?view_only=dadcfc82666140a6ab5a1c3f63b679be.

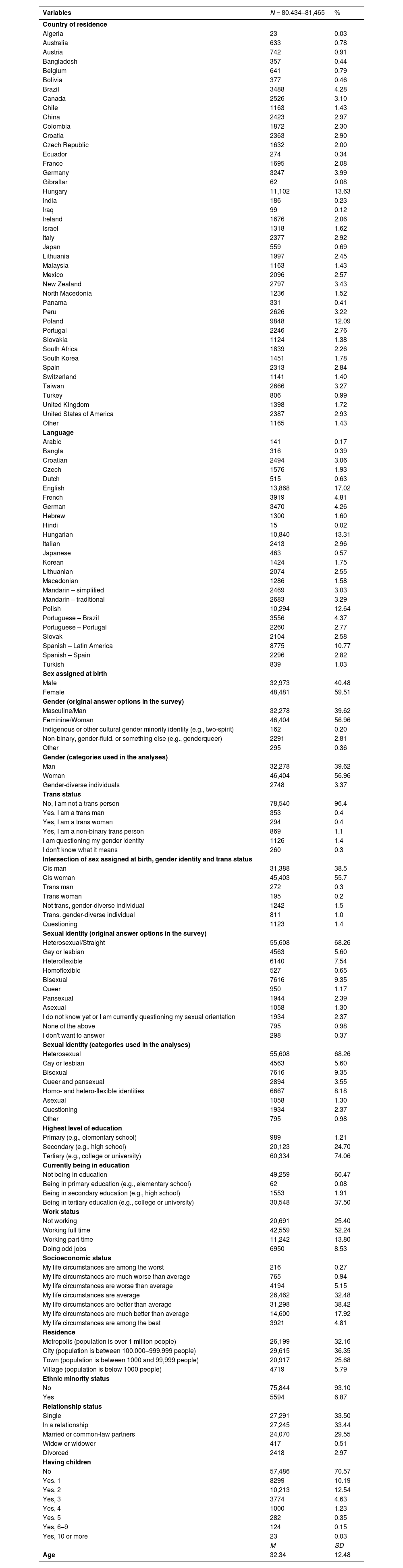

The original dataset contained 82,243 participants (Mage=32.39 years, SD=12.52), out of which 81,465 participants completed the SAHQ (Mage=32.34 years, SD=12.48). A total of 56.96 % of the sample identified as women, 39.62 % as men, and 3.37 % as gender-diverse individual (e.g., non-binary, genderfluid); 4.3 % reported trans identity (i.e., trans woman, trans man or trans gender-diverse individual); 68.26 % reported being heterosexual, 5.6 % gay or lesbian, 9.35 % bisexual, 3.55 % queer or pansexual, 8.18 % homo- or heteroflexible, 1.30 % asexual, 0.98 % another sexual identity, and 2.37 % of respondents were unsure about or questioning their sexual identity. A detailed description of the analyzed sample is presented in Table 1. The sociodemographic description of each country's sample is available at https://osf.io/cj658.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the total sample.

Note. Percentages might not add up to 100 % due to missing data. M = mean, SD = standard deviation.

The wording and translations of all questionnaires used in this study, including the SAHQ, can be found at https://osf.io/jcz96.

Participant characteristicsThe survey battery included several sociodemographic and sexuality-related questions (e.g., age, gender, sex, trans status, sexual identity, relationship status, number of children, education and work status, place of residence, subjective socio-economic status, ethnic minority status, and religious affiliation). For the complete list of variables included in the survey battery, refer to the study protocol (Bőthe et al., 2021).

Participants self-reported their sex assigned at birth, gender identity, trans status, and sexual identity using a range of options provided in the survey (see Table 1).5 Following the preregistered study plan, we defined analytic groups based on these variables. We created three groups based on self-reported gender identity: men, women, and gender-diverse individuals (participants who identified as genderqueer, genderfluid, non-binary, indigenous or other cultural gender-minority identity [e.g., two-spirit], and other gender identity). Based on the intersection of self-reported sex at birth, gender identity and trans status, we created seven groups to examine different groups of cis- and trans-gender individuals (i.e., cis men, trans men, cis women, trans women, non-trans gender-diverse individuals, trans gender-diverse individuals, and participants questioning their gender identities). Sexual identity was grouped into eight categories: heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, queer or pansexual, homo- or hetero-flexible, asexual, other sexual identity, and respondents who were unsure about or questioning their sexual identity. Further details on creating gender-identity-, trans-status- and sexual-identity-based groups can be found in the preregistration document (https://osf.io/8kdzv/?view_only=dadcfc82666140a6ab5a1c3f63b679be). See Table 1 for a full list of the original response options and the categories used in our analysis.

Sexual victimizationDetailed description of the Sexual Abuse History Questionnaire (Leserman et al., 1995) and its two scales (i.e., CSA and AASA scales) can be found in the introduction. Upon previous psychometric examinations, the SAHQ demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and validity (Buczo et al., 2024; Leserman et al., 1995). For the wording of the instructions and items in English, see Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials.

Anxiety and depressionThe six-item anxiety and the six-item depression subscales from the short version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18; Asner-Self et al., 2006; Derogatis, 2001) were used to assess anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively, in the past seven days. The subscales have demonstrated excellent reliability (α=0.90 for both) and measurement invariance across the countries, languages, and gender and sexual identities in the International Sex Survey (Quintana et al., 2024). Participants indicated their answers on a five-point Likert scale (0=“not at all”, 4=“extremely”). Higher scores on these subscales indicate more severe depression and anxiety.

Statistical analysesDescriptive analyses and missing dataThe data analysis followed a preregistered analytic plan (https://osf.io/8kdzv/?view_only=dadcfc82666140a6ab5a1c3f63b679be). Statistical tests were conducted in SPSS v.26 and R. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all items of the SAHQ, and the proportions of participants reporting victimization were reported. Missing values were present on SAHQ items and on gender and sexual identity variables. Participants who did not respond to any of the SAHQ items were excluded from analyses (n = 778), but partial missingness was allowed. Responses were not missing at completely random based on Little's Missing Completely at Random Test (MCAR, χ2=29,178.31, df=3222, p<.001, rates ranging from 0 to 5.6 %). We used the pairwise present method, a similar approach to the full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) method, to handle missing data (Newman, 2014).

Test of structural validity and dimensionalityThe CSA and AASA subscales of the SAHQ were treated as two separate one-factor scales during analyses as recent evidence from a large Hungarian sample indicated that this model is the most appropriate (Buczo et al., 2024). Using the total sample, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on both subscales and used common goodness-of-fit indices to evaluate the model fit: Comparative Fit Index (CFI; ≥.95 for good, ≥.90 for acceptable), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; ≥.95 for good, ≥.90 for acceptable), and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; ≤.06 for good, ≤.08 for acceptable) with its 90 % confidence interval (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). We used the weighted least square mean- and variance-adjusted estimation method (WLSMV) as it is recommended when assumptions of normality are violated, especially in the case of dichotomous items (Brown, 2015).

Further, to assess structural validity, we examined dimensionality of the CSA and AASA scales across country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups. To ensure that a group had an appropriate minimum sample size for CFA, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations (see details: https://osf.io/8kdzv/?view_only=dadcfc82666140a6ab5a1c3f63b679be). A minimum of 510 participants were required to be included in each subgroup for the SAHQ-CSA and 460 for the SAHQ-AASA. Additionally, we conducted measurement invariance analysis to assess construct validity across country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups following our pre-registered analysis plan. Given the scale's dichotomous answer options, only configural and scalar invariance could be tested (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). For further details, please refer to the Supplementary materials (Table S5).

Test of known-group validity and reliabilityHaving experienced CSA or AASA has been consistently linked to higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms (Amado et al., 2015; Dworkin, 2020; Maniglio, 2010). Therefore, to examine know-group validity, we compared respondents who answered yes to any of the twelve SAHQ items vs. respondents who said no by anxiety and depressive symptoms. Significant differences with an effect size around 0.20 were considered small, around 0.50 medium, and around 0.80 large (J. Cohen, 1988). Cronbach's alphas and McDonald's omegas were calculated separately for the CSA and AASA scales to assess reliability.

Occurrence estimates and group comparisonsOccurrence estimates of CSA and AASA are reported and compared across countries, genders, and sexual identities. The occurrence estimates in country-based groups are reported in Table 3, while those in the gender-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups are reported in Table 4. Post-hoc pairwise chi-square tests with Bonferroni-corrected p values for the gender-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups are presented in Tables 5,6,7. These differences may also be examined as a source of validity evidence, compared to patterns of demographic disparities reported in prior literature (e.g., Baams, 2018; Craig et al., 2020; Dworkin et al., 2021; Rothman et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2018; Thoma et al., 2021; Walters et al., 2013). We did not examine country differences due to the large number of groups, the potential bias associated with the study's non-probabilistic sampling methods and the highly varying sample sizes across countries.

Associations between different types of CSA and AASAWe calculated odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals for each item pair of the SAHQ, where an OR>1 indicated an increased likelihood of a certain type of CSA or AASA experience with exposure to another type (see Table 8).

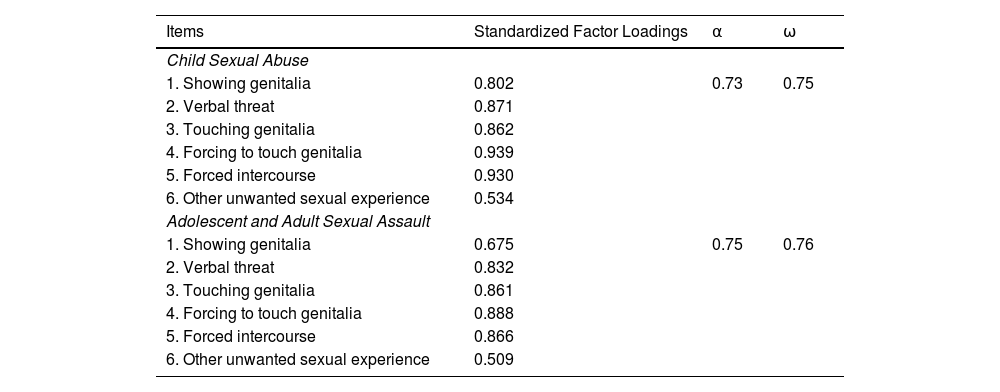

ResultsTest of structural validity and dimensionality for the CSA and the AASA scale in the total sample and in country-, gender-identity-, Trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groupsA first-order, one-factor model was tested on the total sample, separately for the CSA and the AASA scales (Buczo et al., 2024). The CFA demonstrated an excellent fit for both scales (CSA: CFI=0.997, TLI=0.995, RMSEA=0.029 [90 % CI=0.027 to 0.031]; AASA: CFI=0.997, TLI=0.995, RMSEA=0.028 [90 % CI=0.026 to 0.030]). Standardized factor loadings ranged from adequate to good, ranging between 0.53 – 0.94 for the CSA and 0.51 – 0.89 for the AASA scales. Although still within the adequate range (Comrey & Lee, 1992), three items exhibited slightly lower factor loadings, indicating a relatively weaker representation of the underlying construct. Among the items, item 6 (“Have you had any other unwanted sexual experiences not mentioned above”?) demonstrated the lowest factor loadings across both scales (CSA: 0.53; AASA: 0.51). Additionally, item 1 in the AASA scale (“Has anyone ever exposed the sex organs of their body to you when you did not want it?”) exhibited a factor loading of 0.68. Descriptive data of all items, standardized factor loadings, and inter-factor correlations are reported in Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings in the confirmatory factor analysis and reliability indices of the sexual abuse history questionnaire (SAHQ) in the total sample.

Note. All factor loadings were statistically significant at p < .001; α = Cronbach's alpha, ω = McDonald's omega.

CFAs were conducted for both scales in country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups. The one-factor models showed excellent fit in all groups for both scales (CFIs>0.95, TLIs>0.95, RMSEAs<0.08), indicating that the SAHQ subscales have similar structures across different populations. Model fit indices for all country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups are reported in Table S1a-S4b in the Supplementary Materials). Measurement invariance testing yielded scalar invariance across all examined populations (see Table S5 in the Supplementary Materials).

Tests of criterion validity and reliabilityRespondents who experienced any form of sexual victimization reported significantly higher anxiety (t(74,481.68)=−46.96, p<.001, d = 0.34) and depression (t(74,388.22)=−41.96, p<.001, d = 0.34) symptoms, with a small effect size (J. Cohen, 1988). In the total sample, both scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (CSA: α=0.73, ω=0.75; AASA: α=0.75, ω=0.76). Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega coefficients are presented in Table 2.

Gender-, sexual-identity-, and trans-status-based group comparisonsWe observed significant differences between gender and sexual identities and cis vs. trans individuals in the ratios of all types of CSA and AASA experiences reported. Numbers and ratios of respondents reporting any form of CSA or AASA are presented in Tables 3-4. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise chi-square comparisons are reported in Tables 5-7. We have not conducted multi-group chi-square comparisons as, given the number of groups and the sample size of the study, they required an unusually large computational capacity, while being less informative than the pairwise comparisons.

Occurrence rates of CSA and AASA across country-based groups.

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; n = sample size; χ2 = Chi-squared coefficient; *p < .001; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience; occurrence estimates are listed. Only countries with an appropriate minimum sample sizes (in bold) were tested for dimensionality. The minimum sample sizes were determined with Monte Carlo simulation. Darker cells indicate higher prevalence estimates.

Occurrence rates of sexual victimization experiences in gender-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups.

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; n = sample size; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience.

Pairwise comparisons of the occurrence estimates of sexual victimization experiences across gender-based groups.

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience; χ2 = Chi-squared coefficient; Colored cells indicate significant differences between groups after Bonferroni correction.

Pairwise comparisons of the occurrence estimates of sexual victimization experiences across trans-status-based groups.

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience; χ2 = Chi-squared coefficient; Colored cells indicate significant differences between groups after Bonferroni correction.

Pairwise comparisons of the occurrence estimates of sexual victimization experiences across sexual-identity-based groups.

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience; χ2 = Chi-squared coefficient; Colored cells indicate significant differences between groups after Bonferroni correction.

All chi-square pairwise comparisons between genders were significant, with men reporting significantly lower occurrence rates of all types of CSA and AASA than women, and gender-diverse individuals reporting significantly higher rates than both men and women. Considering gender and trans status, cis men reported significantly fewer CSA and AASA experiences than all other groups. There was greater variability in the results regarding other pairwise comparisons, but a pattern emerged whereby cis women reported significantly less CSA and AASA than trans and non-trans gender-diverse individuals and questioning individuals, but they did not differ significantly from trans women and trans men. An important exception from this pattern was CSA with forced intercourse, where all trans, gender-diverse, and questioning individuals reported significantly higher estimates than cis women.

Examining occurrence estimates in sexual-identity-based groups, heterosexual participants typically reported the lowest rates of all types of CSA and AASA, differing significantly from all other groups. An exception was CSA involving unwanted touching of an individual's sexual organs (CSA item 3) and forced intercourse (CSA item 5), where asexual participants, although reporting numerically higher rates, did not differ significantly from heterosexual participants. Queer and pansexual individuals reported the highest rates, differing significantly from even bisexual participants, who, as a general pattern, reported the second highest rates of some types of CSA (item 1, 3, and 6) and all AASA experiences. In CSA involving verbal threats (CSA item 2), being forced to touch a perpetrator's sexual organs (CSA item 4), and forced intercourse (CSA item 5) – where gay or lesbian individuals reported higher rates than bisexual individuals, but lower than queer or pansexual individuals – there were no significant differences between the gay/lesbian and queer/pansexual groups.

Associations between different types of CSA and AASAORs were calculated for all item pair (Table 8). The highest ORs were observed between CSA-CSA (ORs=4.47–56.93) and AASA-AASA (ORs=3.34–19.65) item pairs. This may reflect the accumulation of different types of victimization within survivors’ experiences in either childhood or adolescent and adult years. The strongest association was observed between verbal threats of CSA and CSA involving penetration, and between AASA involving unwanted touching of genitalia and being forced to touch someone's genitalia.

Associations between the manifestations of sexual victimization represented by an odds ratio matrix.

Note. Lower triangle values represent the odds ratio for answering yes to both items in a pair. Upper triangle values represent 95 % confidence intervals. CSA = child sexual abuse; AASA = adolescent and adult sexual assault; 1 = Showing genitalia, 2 = Verbal threat, 3 = Touching genitalia, 4 = Forcing to touch genitalia, 5 = Forced intercourse, 6 = Other unwanted sexual experience. Darker colors draw attention to higher odds ratios. The area within the dashed-line-demarcated rectangle presents associations between CSA and AASA experiences.

ORs between CSA and AASA items were also relatively high (ORs=1.75–13.40), indicating a positive association between childhood and later-in-life unwanted sexual experiences. Respondents who experienced any form of CSA were almost twice as likely to experience AASA. For example, verbal threats of sexual violence and forced intercourse in childhood were both highly associated with verbal threats, being made to touch someone's genitalia and forced intercourse in later life stages. However, we observed wide confidence intervals as a consequence of the large sample size and the relatively low occurrence of certain experiences. This reflects the inherent sensitivity of OR estimates in such scenarios and warrants caution in the interpretation of the results.

DiscussionThere is a large corpus of evidence that underrepresented groups of sexual and gender minorities are more vulnerable to sexual victimization than their non-minority peers (Baams, 2018; Dworkin et al., 2021; Friedman et al., 2011; Rothman et al., 2011; Tobin & Delaney, 2019; Walters et al., 2013). Still, to our knowledge, psychometric examinations of survey measures used to screen for sexual victimization in general populations did not include sexual and gender minority groups. Populations from non-WEIRD countries were also often missing from previous psychometric work. The present study aimed to address this gap by validating the SAHQ across many countries (Leserman et al., 1995), with the inclusion of underserved and underrepresented populations.

Psychometric evaluationBoth the SAHQ-CSA and SAHQ-AASA demonstrated excellent structural validity in all country-, gender-, sexual-identity-, and trans-status-based groups. Measurement invariance testing yielded scalar invariance across all examined populations, indicating that the SAHQ-CSA and the SAHQ-AASA measure the underlying construct similarly regardless of gender, trans status, sexual identity, and country. Both scales showed appropriate criterion validity with clinically relevant constructs (i.e., depression and anxiety symptoms), as well as acceptable reliability. Additionally, the observed pattern of group differences in the CSA and AASA occurrence estimates aligned with well-documented demographic disparities (e.g., Baams, 2018; Craig et al., 2020; Dworkin et al., 2021; Rothman et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2018; Thoma et al., 2021; Walters et al., 2013), further supporting the validity of the scales.

The SAHQ has been scored diversely since its development, reflecting the ongoing lack of consensus in the literature. Some studies have calculated composite scores to create categorical variables (e.g., Grossi et al., 2018; Slavin et al., 2020; Toomey et al., 1993), others have summed the number of “yes” answers (e.g., Estlein et al., 2024), while some others have proposed weighted aggregate scoring methods for modified versions of the SAHQ (e.g., Godbout et al., 2019; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015). To address this inconsistency, we tested the SAHQ from multiple scoring perspectives: including statistics related to both the continuous and dichotomous scoring. Our results (i.e., acceptable-to-moderate values of internal consistency, factor-loadings, and model fit indices) suggest that the items are not closely related to each other but are not independent either. These findings, supported by the high between-items correlations within each scale, may imply that the aggregated scores may represent a latent construct. Furthermore, the scalar invariance we established across country-, gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups suggests that an aggregated score could be meaningfully compared across these groups. Still, we caution against using a simple sum score due to potentially problematic interpretations. The information obtained from the SAHQ does not enable us to interpret whether participants who say yes to multiple items within the CSA or AASA subscales indicate different forms of victimization during multiple, separate events or one event. Higher scores calculated by simply summing the number of yes answers represent being victimized by multiple forms of sexual violence but may not equate with more severe trauma. To avoid misrepresenting trauma severity, we recommend using the SAHQ-CSA and SAHQ-AASA items to create categorical variables (i.e., experienced CSA or not) or weighted total scores (e.g., Godbout et al., 2019; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015).

Gender-, sexual-identity-, and trans-status-based group differencesWe observed significant differences between genders with gender-diverse (e.g., non-binary, genderqueer) individuals consistently reporting the highest, and women reporting the second highest occurrences of all six types of unwanted sexual experiences both in childhood and later in life. The most common manifestation of both CSA and AASA were perpetrators exhibiting sexual organs and unwanted touching of an individual's sexual organs across all genders. Findings from our multinational sample are consistent with the existing literature regarding differences between men, women (Dworkin et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2018), and gender-minority individuals (Baams, 2018; Thoma et al., 2021). To date, sexual victimization of gender-diverse individuals has mainly been studied in North American and British populations, and they have mostly been compared to binary trans identities (i.e., trans men and trans women) (Newcomb et al., 2020; Rimes et al., 2019; Scandurra et al., 2019). Our study provides new cross-cultural evidence that gender-diverse individuals may be associated with higher rates of both CSA and AASA globally.

Taking a closer look at the intersection of gender identity, sex assigned at birth and trans status, we found that overall, trans individuals, non-trans gender-diverse individuals, and participants who reported questioning their gender identity more frequently reported CSA and AASA than cisgender men and women. Specifically, trans men and trans gender-diverse individuals reported the highest rates of all types of CSA and AASA. However, these were only consistently significantly different in comparison with cisgender men. For example, trans women and cis women only differed significantly with respect to CSA involving forced intercourse, but not concerning other types of victimization.

Consistent with previous results and our hypotheses, we observed significantly higher frequencies of all types of CSA and AASA in sexual-minority participants (Dworkin et al., 2021; Rothman et al., 2011; Walters et al., 2013), except for CSA involving unwanted touching of individuals’ genitals and forced intercourse, where asexual and heterosexual participants did not significantly differ. To date, research on childhood and later-in-life sexual victimization has rarely focused on plurisexual identities other than bisexuality, although it was thought that pansexual, queer and other plurisexual individuals may be at even higher risk of victimization than bisexual individuals (Craig et al., 2020; Flanders et al., 2019). In our sample, pansexual and queer participants reported the highest rates of unwanted sexual experiences, significantly differing from bisexual, heterosexual, and homo- and hetero-flexible participants across all types of CSA and AASA, and from gay/lesbian, asexual and “questioning” identities across most types of CSA and AASA.

A potential explanation for the vulnerability of sexual- and gender-minorities that we observed in this large, cross-cultural sample is the often multifaceted and far-reaching effects of stigmatization and discrimination of these individuals. According to the Routine Activity Theory, victimization occurs when three elements converge: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian (L. E. Cohen & Felson, 1979). The marginalization, isolation, and rejection by family and peers may result in limited social support, unstable or unsafe living situations, or mental health challenges that promote vulnerability to sexual victimization (e.g., Cusack et al., 2023). The internalized stigma and potential need to conceal their identities may lead minoritized individuals to seek sexual partners and relationships outside of protected networks. In the absence of sexuality education tailored to their needs, they may take more risk while exploring their diverse sexualities. Additionally, perceived sexual- or gender-minority identity may also motivate sexual violence in some cases (Blondeel et al., 2018).

There is little research as to why plurisexual individuals may be at an even greater risk of sexual victimization than other sexual-minority individuals (Flanders et al., 2019). However, they may face discrimination from both heterosexual and sexual-minority groups (McInnis et al., 2022), resulting in greater social isolation. Additionally, they are often stereotyped as hypersexual and promiscuous, which may be used by perpetrators to justify assaults (Flanders et al., 2017).

Associations between different types of CSA and AASAIn line with previous research and our hypothesis, we observed significant positive associations between all measured types of CSA and AASA. Respondents who experienced any form of unwanted sexual experiences in childhood were at least twice as likely to have experienced sexual assault in their adolescent or adult years. We also noted an even stronger association between different manifestations of AASA-AASA and especially, CSA-CSA experiences, which might indicate a co-occurrence or accumulation of different types of victimization in the experiences of survivors. For example, the likelihood of sexual victimization involving forced intercourse was most closely associated with threats of sexual violence, unwanted touching of sexual organs, and being forced to touch the sexual organs of a perpetrator in both CSA and AASA. We note, however, that answering yes to multiple CSA or AASA scale items did not necessarily refer to separate events; it could refer to different manifestations of violence suffered throughout one or multiple experiences of victimization. Survivors often experience abuse or assaults in relational, prolonged contexts (e.g., CSA by a family member or other guardian, or adult intimate-partner sexual violence), and more severe forms of violence (e.g., rape) are often preceded and accompanied by other abusive acts (e.g., verbal threats of sexual violence) (Andersson et al., 2020; Walters et al., 2013).

Limitations and recommendations for future researchThe generalizability of our results to the broader population may be restricted due to the non-representative sampling, and the adoption of online sampling methods might have introduced selection bias. Although we employed standardized recruitment materials (e.g., posters, online advertisements) and provided standard recruitment guidelines to our collaborators, sample equivalence across countries could not be ensured. For example, individuals who do not have access to the internet may be underrepresented in the study and even more underrepresented in some countries than others as limited internet access and related inequities vary internationally. We collected self-report data, including data on participants’ sexual identity, which may not always align with their sexual behavior (Mishel, 2019). Although self-identification is an important facet of sexuality and our study contributed significantly to the literature with the inclusion of a broad spectrum of previously underrepresented identities, future studies may provide a more comprehensive picture of participants’ sexual lives by incorporating questions regarding sexual attraction (Which gender(s) are you attracted to?) and sexual behavior (Which gender(s) do you have sexual relationships with?). General limitations associated with the ISS are described on the study's OSF page (https://osf.io/n3k2c).

Additionally, measurement biases may occur when measuring sexual victimization retrospectively. Evoking and sharing trauma is a difficult and complex process that may be influenced by many factors (Tener & Murphy, 2015). Memories related to sexual victimization, especially CSA, may become consciously inaccessible due to traumatic mechanisms (e.g., repression, dissociation) (Geraerts et al., 2006). Survivors may be unaware of the event, be unsure if it happened, have difficulty remembering it accurately, not recognize whether what occurred constitutes abuse/assault (Dorahy & Clearwater, 2012; Lab & Moore, 2005; Sorsoli, 2010).

Similarly to many other CSA and AASA scales (Chiang et al., 2016; Dunne et al., 2009; Gil-Llario et al., 2020; Koss et al., 2007; Swahnberg & Wijma, 2003), the SAHQ refers to unwanted sexual experiences. The phrasing “when you did not want it” or “against your will,” however, might exclude some cases of child or adolescent grooming (i.e., a process by which a perpetrator isolates and prepares an intended victim to be compliant with the abuse; Bennett & O'Donohue, 2014), or intimate-partner sexual violence, as they often happen in a context where sexual want and consent are deemed ambiguous, even by the survivor (Fernet et al., 2021). Notably, the criterion of unwanted or non-consensual experience is not needed for the WHO definition of CSA, and sexual interaction between an adult and a child are per se abusive according to the laws of many countries (WHO, 1999).

Although the SAHQ asks about five different forms of sexual victimization, the literature indicates that a wider range of sexual experiences may be considered abusive or otherwise traumatic for individuals (Dworkin et al., 2021). A recent qualitative study analyzed open-ended text responses related to the SAHQ's sixth item (“Have you had any other unwanted sexual experiences not mentioned above?”) and identified at least seven additional forms of sexual violence not captured by the first five items: groping, non-physical coercion, lack of consent due to altered consciousness, verbal abuse, physical harm in the context of consensual sexual activity, violations of consent regarding sexual health and the reproductive system, and breach of ongoing consent (Buczo et al., 2024).

Additionally, the SAHQ provides no information about potential sexual violence that happens in the digital realm. This needs to be addressed in further measurement development as technology-facilitated sexual violence are increasingly common, especially among sexual-minority and gender-nonconforming youth (Gámez-Guadix & Incera, 2021; Hillier et al., 2012), and is reported to be associated with similar outcomes as in-person violence (Patel & Roesch, 2022). Furthermore, sexual and gender minority individuals may face specific forms of sexually violent acts such as homophobic or transphobic sexual harassment or bias-motivated sexual violence in both the online and offline sphere (Messinger & Koon-Magnin, 2019). There is a need for instruments screening for lifetime sexual victimization and revictimization that include a wider range of sexually violent acts to align with recent evidence and the WHO definitions of CSA and AASA.

We note that the impact of sexual victimization may be affected by many characteristics of the experience that the SAHQ does not aspire to cover, such as the exact age of occurrence, the relationship to the perpetrator, the duration and frequency of the victimization, the severity of violence, or the potential disclosure and its consequences (e.g., Ullman, 2007). Although a more comprehensive measure would benefit our understanding of sexual victimization outcomes, ethical review boards often raise concerns about surveying respondents’ traumatic experiences in such depth without readily available expert help. Participant distress research shows that those with a history of sexual victimization indeed respond to trauma-related questions with more distress than non-victims. However, this distress was found to be low to moderate on an absolute scale, and they also reported personal benefits from participating in trauma research (Jaffe et al., 2015).

Conclusions and implicationsWith our study, we aimed to fill a methodological gap and re-examine a widely used screening measure for lifetime sexual victimization. Overall, the psychometric assessment of the SAHQ demonstrated its utility in diverse populations according to gender, sex, and culture. Our cross-country results regarding demographic differences between gender-identity-, trans-status-, and sexual-identity-based groups corroborated previous evidence from WEIRD samples that women, trans or gender-diverse individuals, and sexual minorities appear at greater risk of both CSA and AASA (e.g., Baams, 2018; Canan et al., 2021; Friedman et al., 2011). Findings further revealed a vulnerable group of pansexual and queer individuals beyond the previously identified group of bisexual individuals (e.g., Walters et al., 2013). Additionally, results provided support for the positive association between CSA and AASA experiences and demonstrated that different forms of violence are clustered in a diverse sample involving minoritized subgroups previously often neglected in the sexual victimization literature.

Our study uniquely covered CSA and AASA of various types and severity in a large cross-cultural sample, including non-WEIRD populations where prior data were scarce. Through the course of the study, we made translations in 26 languages freely available to advance cross-cultural research on sexual victimization (see translations at https://osf.io/jcz96). The translation and cross-country validation of the concise SAHQ can offer consistency and standardization in cross-cultural trauma research. The diverse study sample allowed us to report occurrence estimates of various gender- and sexual-minority identities (e.g., pansexual individuals, non-binary individuals) that were previously underrepresented or merged with other minority identities, losing nuance in the process. With this approach, we provided detailed insights into different manifestations of sexual victimization for researchers and clinicians globally. Moreover, we hope to raise awareness about a range of abusive acts and vulnerable populations, and thus inform future prevention and intervention efforts, as well as evidence-based policy creation, including the effective and equitable allocation of resources.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used OpenAI's ChatGPT in order to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FundingThe research was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant numbers: KKP126835). L.N. and M.K. were supported by the ÚNKP-22–3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.; S.W.K. was supported by the Kindbridge Research Institute; Z.D. was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant numbers: KKP126835); M.N.P. was supported by the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling; BB was supported by the FRQSC – Research Support for New Academics (NP) Program during the finalization of this article; C.Y.L. was supported by the Wordwide Universities Network (WUN) Research Development Fund (RDF) 2021 and the Higher Education Sprout Project, the Ministry of Education at the Headquarters of University Advancement at the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU); C.L., J. Billieux and D.J.S. received support from the WUN Research Development Fund (RDF) 2021; G.O. was supported by the ANR grant of the Chaire Professeur Junior of Artois University and by the Strategic Dialogue and Management Scholarship (Phase 1 and 2); G.C.Q.G. was supported by the SNI #073–2022 (SENACYT, Republic of Panama); H.F. was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) (Japan Society for The Promotion of Science, JP21H05173), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (Japan Society for The Promotion of Science, 21H02849), and the Smoking Research Foundation; J.B.G. was supported by grants from the International Center for Responsible Gaming and the Kindbridge Research Institute; K. Lukavská was supported by the Charles University institutional support programme Cooperatio-Health Sciences; K. Lewczuk was supported by Sonatina grant awarded by National Science Centre, Poland, (2020/36/C/HS6/00,005); K.R. was supported by a funding from the Hauts-de-France region (France) called "Dialogue Stratégique de Gestion 2 (DSG2)"; L.C. was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (19BSH117); M.G. was supported by National Science Centre, Poland (2021/40/Q/HS6/00,219); R.C. was supported by Auckland University of Technology, 2021 Faculty Research Development Fund; R.G. was supported by Charles University's institutional support programme Cooperatio-Health Sciences; S.B. was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair; Sungkyunkwan University's research team was supported by Brain Korea 21 (BK21) program of National Research Foundation of Korea.

EthicsThe authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the relevant national and institutional committees' ethical standards on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by all collaborating countries' national/institutional ethics review boards: https://osf.io/e93kf

The authors would like to thank Anastasia Lucic and Natasha Zippan for their help with project administration and data collection, and Abu Bakkar Siddique, Anne-Marie Menard, Clara Marincowitz, Club Sexu, Critica, Digital Ethics Center (Skaitmeninės etikos centras), Día a Día, Ed Carty, El Siglo, Jakia Akter, Jayma Jannat Juma, Kamrun Nahar Momo, Kevin Zavaleta, Laraine Murray, L'Avenir de l'Artois, La Estrella de Panamá, La Voix du Nord, Le Parisien, Lithuanian National Radio and Television (Lietuvos nacionalinis radijas ir televizija), Mahfuzul Islam, Marjia Khan Trisha, Md. Rabiul Islam, Md. Shahariar Emon, Miriam Goodridge, Most. Mariam Jamila, Nahida Bintee Mostofa, Nargees Akter, Niamh Connolly, Rafael Goyoneche, Raiyaan Tabassum Imita, Raquel Savage, Ricardo Mendoza, Saima Fariha, SOS Orienta and Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú, Stephanie Kewley, Sumaiya Hassan, Susanne Bründl, Tamim Ikram, Telex.hu, Trisha Mallick, Tushar Ahmed Emon, Wéo, and Yasmin Benoit for their help with recruitment and data collection.

Rafael Ballester-Arnal1, Dominik Batthyány2, Joël Billieux3,4, Peer Briken5, Julius Burkauskas6, Georgina Cárdenas-López7, Joana Carvalho8, Jesús Castro-Calvo9, Lijun Chen10, Carol Strong11, Giacomo Ciocca12, Ornella Corazza13,14, Rita Csako15, David P. Fernandez16, Hironobu Fujiwara17,18, Elaine F. Fernandez19, Johannes Fuss20, Roman Gabrhelík21,22, Biljana Gjoneska23, Mateusz Gola24,25, Joshua B. Grubbs26,27, Hashim T. Hashim28, Md. Saiful Islam29,30, Mustafa Ismail31, Martha C. Jiménez-Martínez32,33, Tanja Jurin34, Ondrej Kalina35, Verena Klein36, András Költő37, Sang-Kyu Lee38,39, Karol Lewczuk40,41, Chung-Ying Lin42,43, Christine Lochner44, Silvia López-Alvarado45, Kateřina Lukavská21,46, Percy Mayta-Tristán47, Dan J. Miller48, Oľga Orosová49, Gábor Orosz50, Sungkyunkwan University's research team51, Fernando P. Ponce52,53, Gonzalo R. Quintana54, Gabriel C. Quintero Garzola55,56, Jano Ramos-Diaz57, Kévin Rigaud58, Ann Rousseau59, Marco De Tubino Scanavino60, Marion K. Schulmeyer61, Pratap Sharan62, Mami Shibata17, Sheikh Shoib63, Vera Sigre-Leirós3,64, Luke Sniewski65, Ognen Spasovski66, Vesta Steibliene67, Dan J. Stein68, Julian Strizek69, Aleksandar Štulhofer70, Banu C. Ünsal71,72, Marie Claire Van Hout73.

1Departmento de Psicología Básica, Clínica y Psicobiología, University Jaume I of Castellón, Spain, 2Institute for Behavioural Addictions, Sigmund Freud University Vienna, Austria, 3Institute of Psychology, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 4Center for Excessive Gambling, Addiction Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 5Institute for Sex Research, Sexual Medicine, and Forensic Psychiatry; University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf; Hamburg, Germany, 6Laboratory of Behavioral Medicine, Neuroscience Institute, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Lithuania, 7Virtual Teaching and Cyberpsychology Laboratory, School of Psychology, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico, 8William James Center for Research, Departamento de Educação e Psicologia, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 9Department of Personality, Assessment, and Psychological Treatments, University of Valencia, Spain, 10Department of Psychology, College of Humanity and Social Science, Fuzhou University, China, 11Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 12Section of Sexual Psychopathology, Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 13Department of Clinical, Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom; Department of Psychocology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Italy, 14Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Italy, 15Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 16Department of Psychology, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom, 17Department of Neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 18Decentralized Big Data Team, RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project, Tokyo, Japan; The General Research Division, Osaka University Research Center on Ethical, Legal and Social Issues, Osaka, Japan, 19HELP University, Malaysia, 20Institute of Forensic Psychiatry and Sex Research, Center for Translational Neuro- and Behavioral Sciences, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 21Charles University, First Faculty of Medicine, Department of Addictology, Prague, Czech Republic, 22General University Hospital in Prague, Department of Addictology, Czech Republic, 23Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia, 24Institute of Psychlogy, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland, 25Institute for Neural Computations, University of California San Diego, USA, 26University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, United States, 27Center on Alcohol, Substance use, And Addictions (CASAA), University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, United States, 28University of Warith Al-Anbiyaa, College of Medicine, Karbala, Iraq, 29Department of Public Health and Informatics, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka-1342, Bangladesh, 30Centre for Advanced Research Excellence in Public Health, Dhaka-1342, Bangladesh, 31University of Baghdad, College of Medicine, Iraq, 32Universidad Pedagógca y Tecnológica de Colombia, Colombia, 33Grupo de Investigación Biomédica y de Patología, Colombia; Grupo Medición y Evaluación Psicológica en Contextos Basicos y Aplicados, Colombia, 34Department of Psychology, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Croatia, 35Department of Educational Psychology and Psychology of Health, Pavol Jozef Safarik University in Kosice, Slovakia, 36School of Psychology, University of Southampton, United Kingdom, 37Health Promotion Research Centre, University of Galway, Ireland, 38Department of Psychiatry, Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital, South Korea, 39Chuncheon Addiction Management Center, South Korea, 40Institute of Psychology, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, Poland, 41Centre of Excellence in Responsible Gaming, University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar, 42Institute of Allied Health Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 43Biostatistics Consulting Center, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 44SAMRC Unit on Risk & Resilience in Mental Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, 45University of Cuenca, Ecuador, 46Charles University, Faculty of Education, Department of Psychology, Prague, Czech Republic, 47Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Perú, 48College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Australia, 49Pavol Jozef Safarik University in Kosice, Department of Educational Psychology and Psychology of Health, Slovakia, 50Artois University, France, 51Department of Psychology, Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea, 52Departamento de Psicología, Universidad Católica del Maule, 53Núcleo Milenio sobre Movilidad Intergeneracional: Del Modelamiento a la Política Pública (MOVI), 54Departamento de Psicología y Filosofía, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Arica y Parinacota, Chile, 55Florida State University, Republic of Panama, 56Sistema Nacional de Investigación (SNI), SENACYT, Panama, 57Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Privada del Norte, Lima, Perú, 58Picardie Jules Verne University, 59Leuven School For Mass Communication, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 60Department of Psychiatry, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, St. Joseph's Health Care London and London Health Sciences Centre. London, Canada; Lawson Research Institute, London, Canada; London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute, London, Canada; Departmento e Instituto de Psiquiatria, Hospital das Clinicas; and Experimental Pathophysiology Post Graduation Program, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, 61Universidad Privada de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 62Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi -110029, India, 63Department of Psychology, Shardha University, India, 64Institute of Legal Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospitals (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 65Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand, 66Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Skopje, 67Laboratory of Behavioral Medicine, Neuroscience Institute, Lithuanian University of Health sciences, Lithuania, 68SAMRC Unit on Risk & Resilience in Mental Disorders, Dept of Psychiatry & Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, 69Austrian Public Health Institute, Austria, 70Department of Sociology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 71Doctoral School of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, 72Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, 73Office of the VP Research, Innovation and Impact, South East Technological University, Ireland.

*The Sungkyunkwan University's research team comprises Dr. H. Chang and Mr. K. Park

The Sungkyunkwan University's research team comprises Dr. H. Chang and Mr. K. Park

A list of the members of the International Sex Survey Consortium can be found in the Appendix.

Although we report the occurrence estimates of CSA and AASA in country-based groups, we did not examine their differences due to the large number of groups and the potential bias associated with convenience sampling and varying sample sizes. Furthermore, prior epidemiological research has highlighted a wide range of reported occurrence estimates across different nations. These variations may be attributed to differences in the definitions of sexual victimization utilized by previous studies, the diverse array of observed abusive acts, the lack of cross-culturally validated scales, and the relative scarcity of robust data from non-WEIRD countries. This would introduce potential bias into the comparison of our findings with those of previous studies.

In our study, we consistently and exclusively use the term “gender-diverse individuals” for gender minorities who do not identify with the binary genders of ‘men’ and ‘women,’ regardless of their trans status (e.g., genderqueer, genderfluid, non-binary, indigenous or other cultural gender minority identity [e.g., two-spirit], and other gender identities). The term “gender minority individual” is used more broadly, referring to both non-binary gender identities and transgender individuals.

Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, and Romania were included in the study protocol paper as collaborating countries (Bőthe et al., 2021); however, it was not possible to get ethical approval for the study in a timely manner in these countries. Chile was not included in the study protocol paper as a collaborating country (Bőthe et al., 2021) as it joined the study after publishing the study protocol. Therefore, instead of the planned 45 countries, only 42 individual countries were considered in the present study; see details at https://osf.io/n3k2c.

Advertisement materials and examples of media coverage can be accessed at https://www.internationalsexsurvey.org/ and https://www.facebook.com/internationals3xsurvey.

In our study, gender identity refers to an individual's self-perception of their gender. It exists on a continuum and may not always align with one's sex assigned at birth (Warner, 2016). Trans status refers to whether an individual identifies as trans. Sexual identity refers to how individuals define themselves sexually. It is a multidimensional construct that may encompass sexual orientation, behavior, gender identity, socio-sexual identity, and erotic identity (Crowell, 2020). Participants in this study self-reported their sex assigned at birth, gender identity, trans status, and sexual identity. The terms were not predefined for them; rather, participants categorized themselves based on their own understanding and identification with the provided options.