Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a chronic digestive condition that requires continuous monitoring by healthcare professionals to determine appropriate therapy and manage short- and long-term complications. Telemedicine has become an essential approach for managing chronic conditions such as IBD, improving care accessibility and continuity, decreasing hospitalization rates, and optimizing patient follow-up. It enables rapid treatment adjustments and encourages patient self-management. Additionally, it reduces the burden on the healthcare system by decreasing unnecessary in-person visits and provides real-time support, thereby improving quality of life and clinical outcomes.

The objective of this position statement by the Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) is to establish recommendations for the use of telemedicine in its different modalities (teleconsulting, telemonitoring, mobile applications and telepharmacy) for patients with IBD and address the legal, ethical, and technical aspects necessary for its proper implementation.

La enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) es una enfermedad digestiva crónica que requiere una monitorización continua por parte de los profesionales de la salud para determinar la terapia adecuada y el control de las complicaciones a corto y largo plazo. La telemedicina ha emergido como una herramienta crucial en la gestión de enfermedades crónicas como la EII, para mejorar el acceso y la continuidad del cuidado, reducir hospitalizaciones y optimizar el seguimiento de los pacientes. Ésta permite ajustes rápidos en el tratamiento y fomenta la auto-gestión por parte del paciente. Además, disminuye la carga del sistema de salud al reducir visitas presenciales innecesarias y brinda soporte en tiempo real, mejorando la calidad de vida y los resultados clínicos.

El objetivo de este documento de posicionamiento del Grupo Español de Trabajo de Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) es establecer recomendaciones sobre el uso de la telemedicina en sus diferentes modalidades (teleconsulta, telemonitorización, aplicaciones móviles, telefarmacia) en pacientes con EII y abordar los aspectos legales, deontológicos y técnicos necesarios para su correcta implementación.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disorder involving relapses, which can lead to disability and poor educational and occupational performance with negative effects on social activities and quality of life and increased healthcare costs.1,2 IBD requires ongoing treatment and follow-up with the aim of reducing structural damage and long-term complications. However, traditional monitoring with face-to-face visits can often be difficult to adapt to each patient's particular disease course and lifestyle. In addition, there is high non-adherence with treatment among adults and adolescents with IBD,3–5 which significantly increases the risk of a flare-up.6–8 These factors decrease the effectiveness in controlling disease activity and lead to increased healthcare costs.9

The progressive increase in the incidence of IBD in Spain and other industrialised countries,10–13 combined with the considerable use of healthcare resources by affected patients, reflects the growing medical, social and economic impact of this disorder.14

In order to provide solutions to this growing demand, information and communication technologies (ICT) have been used to provide remote health services, known as telemedicine. This modality allows healthcare professionals to assess, diagnose, treat and monitor patients without the need for their physical presence. The advantage of these technological systems lies in the efficient use of resources, with better doctor-patient communication and the ability to provide educational elements adapted to the needs of each patient, which potentially contributes to their empowerment and the early optimisation of treatment at each stage of the disease.

Telemedicine has been successfully used for the management of other chronic conditions,15–17 and in the last ten years it has begun to be used in the management of IBD, especially in mild to moderate cases. ICT used in patients with IBD vary depending on the technological elements, the technical functions used and their clinical or educational applications. These have been used to improve communication between different healthcare professionals and patients, overcome physical limitations in healthcare delivery, and address issues that influence IBD activity, such as non-adherence to treatment and the behavioural and psychological factors involved.18,19

In recent years, the use of remote monitoring of IBD has increased in clinical practice, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult or even impossible for patients to access services in person. Since then, telemedicine has emerged as a promising option for reorganising the structure of IBD patient care, at a time when European healthcare systems are experiencing funding and sustainability problems. A group of experts in IBD telemedicine, including specialists in gastroenterology, pharmacy, informatics and forensic medicine, have been involved in the development of the recommendations in this document.

TeleconsultationDefinition and its utilityTeleconsultation was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as early as 1997 as a modality of remote healthcare which enables communication between healthcare professionals or between healthcare professionals and patients.20 There are a number of advantages to the use of teleconsultation over the usual face-to-face consultation, particularly the following:

Extension of the medical service.

- none-

Reaching patients in geographically remote areas or areas with reduced mobility.

- none-

Enable multidisciplinary approach to complex cases, especially between hospitals which do not have all specialities available.

Optimisation of time and costs.

- none-

Appointments do not require a trip to the health centre, which saves time and costs, especially for the patients.

- none-

From the point of view of the healthcare professional, care times can be better optimised and unnecessary waiting times avoided.

Recommendation: in remote geographic areas, teleconsultation should be prioritised to optimise time and direct and indirect healthcare costs.

TypesTeleconsultation can be very useful in patients with chronic conditions such as IBD who are managed according to established protocols and algorithms and who make multiple visits to healthcare facilities.19,21,22

Non-face-to-face consultations can take place between:

- a

Healthcare professionals

- a

These are electronic consultations on diagnosis or patient management between the gastroenterologist and primary care physicians or other specialists. In some autonomous regions in Spain, this type of consultation is already established and regulated with the IBD units for the rapid management of suspected IBD.

- b

Healthcare professional and patient

- b

In this case, it is a matter of replacing the usual face-to-face consultation with other forms of remote consultation:

- none-

Telephone consultation: in this mode, information is transmitted in real time by telephone. The patient receives information about test results or health recommendations from the gastroenterologist or specialist nurses. Monitoring of the disease and certain changes in the therapeutic approach can be made.

- none-

Consultation by video call: in this mode, information is transmitted in real time by means of image and sound. It is closer to a face-to-face consultation, as transmission of non-verbal information can be taken into account, but limited in that a full physical examination is not possible.

There are a few studies on the use of teleconsultation in patients with IBD, although in some of them they do it through a telemonitoring tool.

Krier et al. conducted a randomised study in 34 patients with IBD in which they demonstrated that teleconsultation via video calls provided comparable patient satisfaction with face-to-face consultations, and it was also positively rated by physicians.23 Similarly, Li et al. evaluated a telemedicine system with virtual appointments in 48 patients with IBD and concluded that 77% of patients preferred virtual consultations, highlighting the savings in time and money without compromising quality of care.24

IBD live is an example of teleconsultation between healthcare professionals. It is a multidisciplinary videoconferencing platform (gastroenterologists, surgeons, pathologists, radiologists and other specialists) for the review of cases and exchange of ideas on the management of patients with IBD.25

However, no studies have been conducted to define in which type of patients teleconsultation is most useful, or in which patients it should be avoided. Moreover, there are no protocols for use of the different variants. We will therefore draw on the results of two surveys conducted during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in which the IBD units in Spain participated in collaboration with the scientific societies to provide recommendations for this position paper.26,27

In the first study, a survey was conducted through the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] to find out how consultations were managed during the COVID-19 pandemic in IBD units in Spain. Teleconsultation was a key measure for being able to continue patient care in the midst of the health crisis. According to the survey (54 responses from IBD gastroenterologists), 100% of IBD units discontinued elective face-to-face consultations and switched to telephone support. In addition, 40% of centres supplemented this service with email consultations and 13% even used social media to update patients on the situation with IBD and COVID-19. This change helped to better manage medical resources, as many endoscopic and elective surgical procedures were delayed. In general, IBD units adopted structural and organisational measures uniformly, adapting quickly to the new situation imposed by the pandemic.27

Subsequently, another survey of physicians (gastroenterologists, paediatricians and coloproctologists) from scientific societies in Spain (GETECCU and the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology] and the Sociedad Española de Coloproctología [Spanish Society of Coloproctology]) showed the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated adoption of this mode of non-face-to-face consultation. Prior to the pandemic, doctors did most consultations face-to-face (93.3%). However, during the pandemic, 51.3% of doctors relied mainly on telephone consultation. These did not account for all consultations as in the previous survey, as coloproctologists also participated, and the main disadvantage of teleconsultations, according to 58.4% of the respondents (269 answers), was the fact that they could not perform a proper physical examination. In addition, 42.4% of the doctors indicated that remote consultations took more time than face-to-face consultations. Despite these difficulties, teleconsultation made it possible to ensure patient follow-up during the pandemic.26

Recommendation: we recommend the use of teleconsultation for most patients, except those with severe flare-ups, active perianal disease or in the immediate postoperative period, where detailed face-to-face clinical assessment is required.

Telephone consultationAlthough there is much variability in the use of telephone consultation, in general we could recommend its use in the following cases:

- none-

Follow-up of stable patients with an established relationship with the healthcare team, who find it difficult to travel to face-to-face appointments.

- none-

Rapid assessment in the case of contact for symptoms of flare-up (in this case and depending on possibilities this could be medical or specialised nursing staff).

- none-

Information to the patient after committees or consultations with other specialities.

- none-

Communication of pending results.

With regard to the patient profile in which it can be used, the group of experts considers that age, educational level, training in the disease itself and confidence in the healthcare team are key factors that affect implementation. In addition, it is essential that the patient accepts this form of follow-up.

Telephone consultation should be avoided in the following situations:

- none-

In the first consultations, where it is necessary to establish a good relationship between the patient and their healthcare team.

- none-

Patients with active perianal disease or symptoms consistent with severe flare-ups requiring physical examination.

- none-

Prior to significant treatment changes requiring detailed information (for example, initiation of biologics, immunosuppressants, small molecules).

- none-

Patients with poor adherence to follow-up and treatment.

- none-

Older patients with hearing or comprehension problems without a caregiver who has their consent to attend the telephone consultation.

Recommendation: telephone consultation should be avoided at first visits, in cases of active perianal disease or severe flare-ups, when treatment changes are required, in patients with poor adherence or patients with hearing or comprehension problems.

Video callsImplementation of video calling is still limited in our setting, and technological improvements are needed to enable routine use.

Where available, being able to observe non-verbal communication and the capacity for some physical assessment (for example, skin lesions) makes its use more akin to a face-to-face consultation, except in situations where a full physical examination is required (for example, perianal disease or assessment of abdominal mass).

It has been found that different socio-cultural factors can influence the success of monitoring through video calls. In the United States, several studies conclude that older, less educated, less wealthy and black patients are more likely not to use or not successfully complete remote consultations.28–30 However, these data come from a different socio-cultural context than ours and have not been consistent across studies. In fact, changes in the profile of patients using telemedicine have been observed since the COVID-19 pandemic.29,31

Recommendation: we recommend the use of video calls in any patient profile, except when a full physical examination is required.

Consultation by emailIn general, the use of email is not routine for patient follow-up like face-to-face or teleconsultation. The aim with email is to provide a quick and easy way of contacting the unit in certain situations such as:

- none-

Specific questions about treatment, or about possible interactions or contraindications of treatment indicated by other specialists.

- none-

Initial contact after the development of symptoms.

- none-

Resolving administrative queries (for example, appointments or test forms).

- none-

Specific recommendations following review of results.

Recommendation: we recommend using email for brief administrative questions or questions about the disease and its treatment.

TelemonitoringDefinition and objectiveTelemonitoring is the most widely used form of telemedicine in IBD to date. It is based on the continuous and structured monitoring of health data self-recorded by patients in their own environment. The aim is early detection of problems related to the disease or treatment, so the management plan can be adapted to the patient's needs at any time.

What are the advantages over face-to-face care?Telemonitoring platforms typically function as triage systems, but beyond their diagnostic function, they are also involved in treatment adjustment and patient education.32 In the context of IBD, the telemonitoring systems evaluated in clinical trials are managed by healthcare staff. In the last 10 years, most of them have been using web-based systems through mHealth (mobile health) programmes, although some of them have also combined the use of email and telephone.

Telemonitoring of IBD is a safe and effective management option and reduces the duration of flare-ups.33–36 In this regard, the Telemonitorización de la Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (TECCU) [Telemonitoring of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] platform has been shown to improve clinical outcomes, quality of life and social activities in patients with moderate/severe IBD.37 The positive results have even been replicated in a recent GETECCU multicentre study. Using this platform in 24 hospitals in Spain, follow-up via TECCU has demonstrated non-inferiority to face-to-face care in inducing and maintaining clinical remission in the short term. It therefore represents an effective and alternative monitoring method to routine medical care.38

In addition, telemonitoring together with tele-education promotes patient empowerment, which is associated with a reduction in face-to-face visits and hospital admissions.34,37,39 A pioneering cost-effectiveness study with the TECCU platform and subsequent studies have shown that telemonitoring is a cost-effective management option, not only in terms of direct cost savings, but also from a social perspective.40–43 However, a Danish retrospective population-based study showed that telematics monitoring may not be cost-effective in patients receiving biologic drugs.44 Whatever the case, one of the limitations of this study is the lack of documenting of some of the indirect costs, which in a Spanish report represented 46.5% of the total.45

What resources does an inflammatory bowel disease unit need to use telemonitoring systems?Most telemonitoring platforms have been evaluated in IBD referral units. These units have specialised multidisciplinary groups, as well as a series of technical resources and protocols which guarantee comprehensive healthcare based on the best available evidence.46 Outpatient follow-up of IBD patients combines face-to-face and telematic follow-up, mainly by telephone and email. Indeed, during the COVID-19 pandemic, these were the main resources used.26,27,47–50 However, the use of validated telemonitoring systems has been the exception so far, because they require a number of additional resources.

Telemonitoring in IBD has mostly been done with programmes in which nurses play a central role.34,35,37,39,51,52 It is advisable to have at least one member who is a specialised nurse, who can resolve some of the alert situations that might occur during follow-up or contact and put the medical staff and the different specialists involved in touch. The health outcomes obtained and costs incurred with telemonitoring up to now should therefore be considered in this context, as they might be different in centres without these human resources. Moreover, it is essential that both healthcare staff and patients are trained in their use.

In terms of the technical resources required, it is necessary to use systems whose safety, effectiveness and economic impact have been assessed. It is important to involve both healthcare professionals and patients throughout the process of design, development and implementation of the platforms, in order to promote their usability and acceptance.53 In addition, there is a need to develop software whose interoperability allows the integration of data into hospital information systems (HIS). This process can be done securely through the use of electronic identification systems, firewalls and encryption methods on mobile devices to prevent sharing by other apps.54

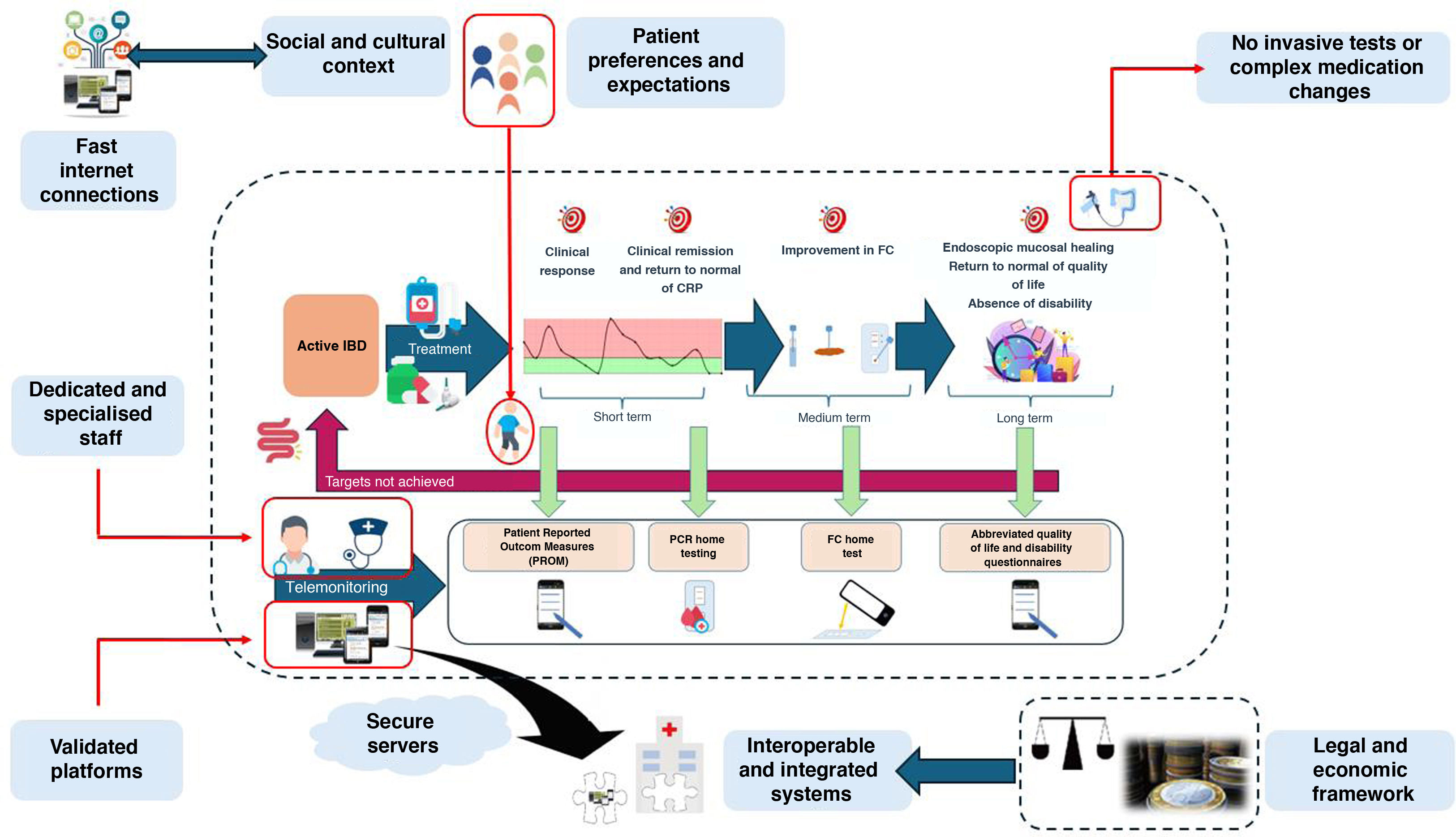

Lastly, a number of external factors have to be taken into account which determine the context in which telemonitoring takes place. For example, the legal and cultural framework governs the actions we are able to carry out safely and in an acceptable manner for the population. In addition, consideration should be given to the reimbursement channels available, which are not standardised in most countries.

Recommendationswe recommend that IBD units have at least one trained and dedicated member of staff (usually specialised nurses) to deal with alerts generated during telemonitoring.

It is recommended to use interoperable systems whose safety, efficacy and economic impact have been evaluated in clinical trials.

Remote medical activity needs to be adapted to the legal, cultural and economic framework in which it takes place.

What resources do patients need to use telemonitoring systems?Telemonitoring of IBD in the last 10 years has been based on mHealth systems.32 Smartphones and tablets have mainly been used, with these being widely accessible resources for the population in our setting. According to a recent report, 57% of the world's population accesses the internet via mobile devices. This percentage rises to 79% in Europe and Central Asia, where only 2% live in areas without access to a mobile broadband network.55

In any event, patients must be able to use telemonitoring platforms. Although 64% of the Spanish population currently has basic skills in handling digital resources, a significant percentage may still have difficulties in using them well. It is therefore essential to consider the "digital literacy" of the users.56 Certain mental and physical issues (such as hearing problems) may also hinder communication, although these can also be a limitation for face-to-face visits.

The need for responsible use of mobile devices in an appropriate environment should be emphasised. Smartphone abuse is associated with psychiatric, cognitive and physical disorders, in adults as well as adolescents.57,58 It is therefore important to have a balance between telematic and face-to-face follow-up, adapting it to each patient's situation, to avoid generating social isolation or other harmful effects associated with new technologies. Last of all, patients need to access the platforms from somewhere quiet and private, to ensure the communication of sensitive data without threatening their privacy or that of the healthcare staff.

Recommendation: we recommend selecting patients who have fast internet connections via mobile devices, as well as the skills to use them correctly and responsibly.

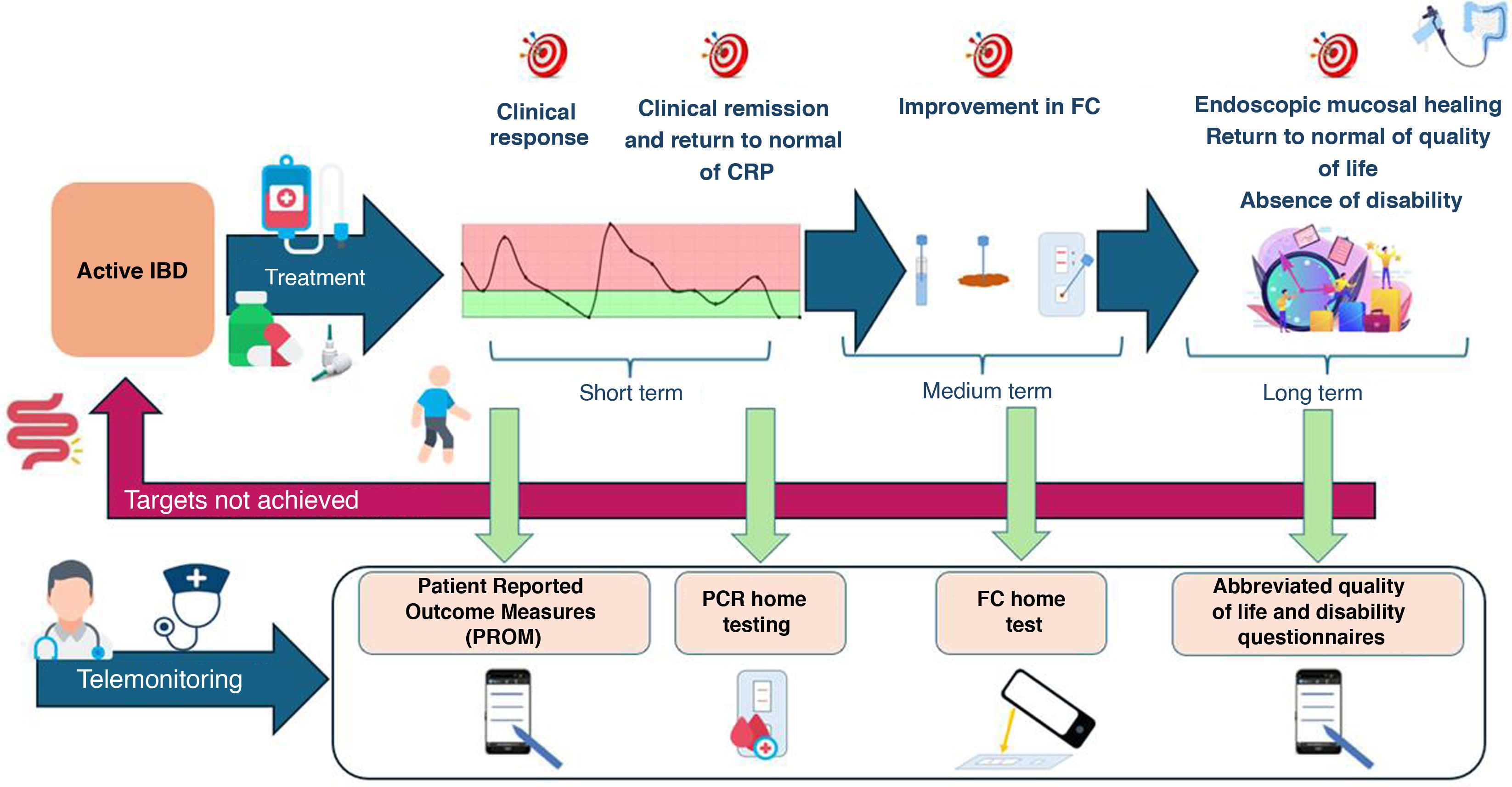

Parameters measurable by telemonitoring in inflammatory bowel diseaseTelemonitoring platforms make it possible to assess most of the goals of the "treat to target" strategy. Proposed in the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative, this strategy aims to change the long-term course of IBD through optimised management. The strategy suggests continuous monitoring of inflammatory activity, and endoscopic mucosal healing, return to normal of quality of life and freedom from disability are set as long-term goals59 (Fig. 1).

Treat to target telemonitoring in adults with IBD.

Adapted from ref.59

According to this initiative, disease remission should be defined on the basis of clinical indices and endoscopic criteria. For this we have Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROM), which are indices recorded by the patients themselves. The Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) and the Harvey-Bradshaw index have been used in telemonitoring programmes,33,35,37,39 with good agreement between their paper and online versions.60–62 Also, the clinical parameters of the Mayo index correlate well with endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis (UC).63 In fact, simpler indices such as PRO-2 have been developed based on the questions in these indices for both UC and Crohn's disease (CD) patients. New PROM have even been validated for specific use through telemedicine programmes.54,64

Nevertheless, beyond the use of clinical indices, remission needs to be confirmed by objective markers of inflammation. Home C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (FC) tests are now available and their use in combination with PROM enables more accurate prediction of endoscopic activity.65,66 Based on this principle, a new PROM called "Monitor IBD At Home" was developed. In both its CD and UC versions, combination with FC gave it high sensitivity for assessing endoscopic activity.64

Moreover, in STRIDE-II, quality of life and disability have been added as long-term objectives, because they are complementary parameters related to inflammatory activity. As regards these objectives, we have the IBDQ to measure quality of life and the IBD disability index to measure disability. Although abbreviated forms of these questionnaires have been validated, they may still need to be simplified for use in daily clinical practice.67–69

Lastly, other efforts to assess perceived quality of care through Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREM) are still in early stages.70,71

Recommendation: we recommend measuring inflammatory activity remotely with the combination of PROM and biomarkers, preferably with FC. We also recommend monitoring quality of life and disability, using validated, shortened versions of the specific questionnaires.

Utility of home biomarker testsSeveral biomarker tests have been designed for the patients themselves to measure inflammatory activity objectively and rapidly in their own environment. Interest in the development of home-based tests has focused on FC, which has shown greater sensitivity for detecting inflammatory activity than other markers such as lactoferrin or CRP.72 FC tests are based on kits which analyse stool samples by immunochromatography. The result is read using a smartphone camera, which uses a specific app to send the result to a server accessible to healthcare staff. Its non-invasive nature and relatively low cost make it a useful tool for diagnosis, monitoring and treatment adjustment in IBD.

Several home-based FC tests have shown a 76–87 % concordance when compared with ELISA tests from the same company.73 With values ≤500 μg/g, the differences between rapid tests and ELISA are not so great that they would lead to misinterpretation of inflammatory activity in the majority of measurements. However, the margins of error are wider when the values are >500 μg/g. To avoid even greater differences in results, it is essential to use home tests from the same company as the ELISA method we use in our laboratories. In any event, we need to be aware that compliance with home-based FC tests is around 50%.74–76

Tests have been developed to measure biological drug levels at home from a dried blood sample, with the potential advantage of bringing forward a result that can currently take several weeks.77–79 However, further studies are needed to determine correlation and comparability with traditional methods.

Recommendation: home FC test results can be considered reliable when values are ≤500 μg/g. If higher values are obtained, we recommend assessing inflammatory activity by other methods. For patients who are motivated to use them, the tests should be from the same company as the ELISA method in our laboratory.

Indications not recommended for follow-up by telemonitoringIt is important to remember that telemonitoring systems are asynchronous and are designed to attend to patients during working hours.34,37,51,80 They are therefore able to handle health demands and alert situations within 24−72 hours, but are not generally designed to handle emergencies. Patients need to be aware of these time frames to ensure that healthcare is provided in accordance with realistic expectations while avoiding healthcare overload.

Telemonitoring has not been used to make medication adjustments. Dose adjustments of oral and topical corticosteroids or salicylates have been carried out in clinical trials, but no procedures for changing immunosuppressants or biologics are specified.33,37,51,52,80,81 As an exception, dose adjustment of infliximab during the maintenance phase of treatment has been evaluated,82 but no strategies have been defined to start biologics or "switch" or "swap" to other biologics telematically. Moreover, with current technical resources, remote invasive testing is not feasible in the context of IBD.

It is relevant that most studies have specified suffering from an uncontrolled medical or psychiatric comorbidity as an exclusion criterion.33,35,37,39,51,80 Patients with a stoma, ileorectal anastomosis, ileoanal pouch, or those with a probable risk of surgery during the study period (usually six to 12 months) were also excluded.33,80,81 The exclusion of patients undergoing surgery or at risk of surgery has probably been motivated by the need for an adequate physical examination in this context. Therefore, in the initial assessment of a patient starting follow-up with the clinic, it may be preferable to have face-to-face contact, both for an adequate physical examination and to initiate the doctor-patient relationship.83

It is also important to note that most studies have not assessed the impact of telemonitoring in women during pregnancy.33,35,37,75,80,81

Recommendation: we do not recommend the use of telemonitoring for:

- 1

Emergency care.

- 2

Making adjustments or changes to advanced pharmacological treatment (biologics or small molecules).

- 3

Patients with a recent stoma (first year).

- 4

Patients at risk of surgery within six to 12 months.

- 5

Performing invasive tests.

As described in the above section on teleconsultation, the use of telemonitoring can also be influenced by differences between healthcare systems and different economic and socio-cultural factors. However, the particular influencing factors have not yet been fully identified in our setting. In this situation, it is even more important to come to an agreement with the patient on the most appropriate follow-up method, according to their needs and preferences.

Recommendation: we recommend considering patients' needs and preferences with regard to face-to-face follow-up or telemonitoring of IBD at each stage of the disease.

As a summary of the above points, Fig. 2 specifies the different external factors that affect the process of IBD telemonitoring.

Applications available for patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseWhile we have seen a major therapeutic breakthrough over the last ten years in IBD, an even more revolutionary breakthrough has taken place in the way we access information, communicate and record and monitor the world around us. Because of the chronic nature of the disorders and because they primarily affect young people, patients with IBD benefit from these platforms as they enable them to take a more active part in their own disease management and self-care. This has been reported in several studies as a need expressed by patients with IBD; a desire for sufficient information, greater involvement in their treatment and a more active role in the management of their disease.84 The answer as to how to build these bridges to greater patient autonomy does seem, in part, to lie in the use of new technologies.53,85

Recent studies in France report that around 50% of patients in primary care aged 18–65 used apps to monitor their health.86 It is possible, however, that the desire to use these apps decreases with age. This was found in a UK study, which not only reported lower mobile app use among older patients, but also that their treating physicians tended to recommend the use of mobile apps less to them compared to younger populations.87 However, this trend is likely to change in light of the speed at which developments in this area are occurring, and more so with the recent expansion of artificial intelligence.

Mobile apps for IBD patients have become an increasingly popular tool for the management of IBD, although they are probably still underused compared to other chronic diseases. These apps can offer a variety of functions to help patients monitor their symptoms, track their progress, learn about their disease and communicate with their doctors.88 However, as internet sources and apps providing information to patients multiply, there are growing concerns about the quality of information and difficulties in finding answers to specific patient questions. Easily accessible mobile health applications with content created by healthcare professionals may be the best way to address these issues.89

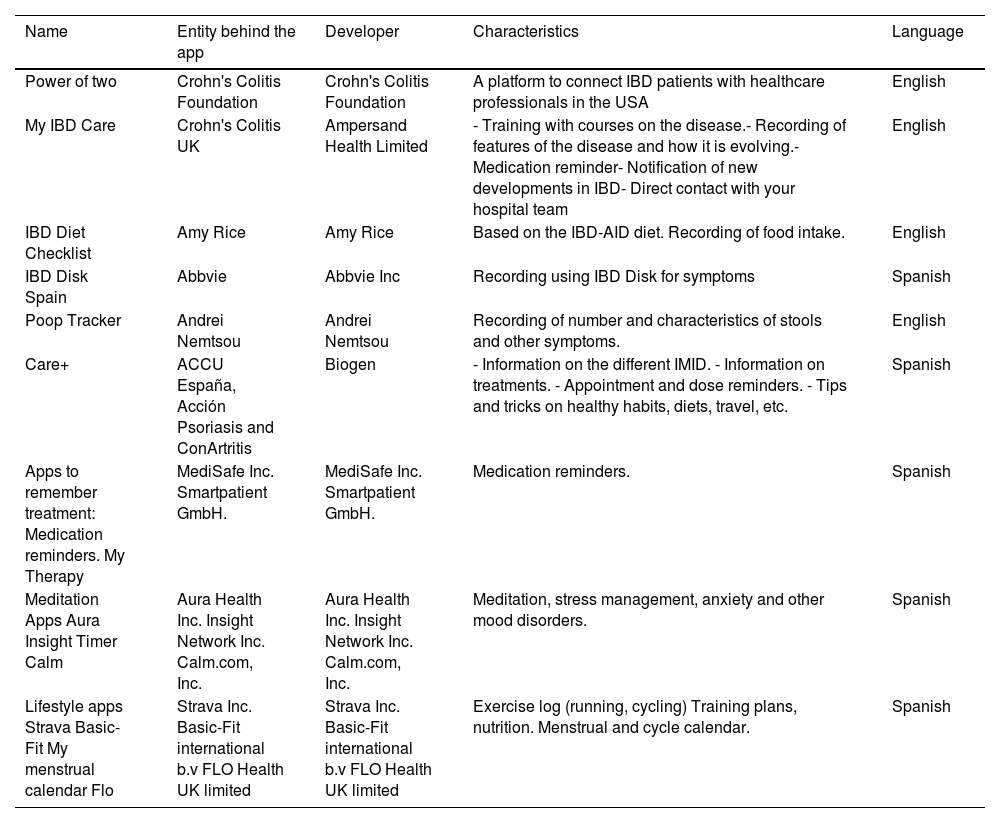

So far, the available apps are enabling symptom tracking (for example, recording of flare-ups, pain or number of bowel movements), IBD education (access to quality treatment and lifestyle information), communication with healthcare staff, medication reminders and self-management tools (for example, meditation, relaxation techniques and emotional support) (Table 1). In addition, social networking apps such as Instagram, X (previously twitter), TikTok and others, include a multitude of profiles of patients, healthcare professionals, societies and associations which promote knowledge, inform patients and promote advocacy, bringing the knowledge closer to all audiences.90,91

Free mobile apps designed for open-access patients (excluding artificial intelligence platforms).

| Name | Entity behind the app | Developer | Characteristics | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power of two | Crohn's Colitis Foundation | Crohn's Colitis Foundation | A platform to connect IBD patients with healthcare professionals in the USA | English |

| My IBD Care | Crohn's Colitis UK | Ampersand Health Limited | - Training with courses on the disease.- Recording of features of the disease and how it is evolving.- Medication reminder- Notification of new developments in IBD- Direct contact with your hospital team | English |

| IBD Diet Checklist | Amy Rice | Amy Rice | Based on the IBD-AID diet. Recording of food intake. | English |

| IBD Disk Spain | Abbvie | Abbvie Inc | Recording using IBD Disk for symptoms | Spanish |

| Poop Tracker | Andrei Nemtsou | Andrei Nemtsou | Recording of number and characteristics of stools and other symptoms. | English |

| Care+ | ACCU España, Acción Psoriasis and ConArtritis | Biogen | - Information on the different IMID. - Information on treatments. - Appointment and dose reminders. - Tips and tricks on healthy habits, diets, travel, etc. | Spanish |

| Apps to remember treatment: Medication reminders. My Therapy | MediSafe Inc. Smartpatient GmbH. | MediSafe Inc. Smartpatient GmbH. | Medication reminders. | Spanish |

| Meditation Apps Aura Insight Timer Calm | Aura Health Inc. Insight Network Inc. Calm.com, Inc. | Aura Health Inc. Insight Network Inc. Calm.com, Inc. | Meditation, stress management, anxiety and other mood disorders. | Spanish |

| Lifestyle apps Strava Basic-Fit My menstrual calendar Flo | Strava Inc. Basic-Fit international b.v FLO Health UK limited | Strava Inc. Basic-Fit international b.v FLO Health UK limited | Exercise log (running, cycling) Training plans, nutrition. Menstrual and cycle calendar. | Spanish |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Some of the initial considerations when choosing an app are based on its functionalities, ease of use and understanding, reliability, data privacy and compatibility with the mobile device. Additionally, many of the apps specifically designed for IBD are in English and this may limit access to Spanish-speaking audiences (Table 1).

Lastly, the recent expansion of artificial intelligence is revolutionising the healthcare sector, including patient monitoring and management.92 The application of artificial intelligence in remote monitoring devices, including using apps (for example, for monitoring sleep, physical activity or vital signs), enables patterns to be identified and predictions to be made, making it an invaluable tool for chronic diseases like IBD which cause flare-ups, where there can be a great deal of uncertainty. Among other functions, the use of "chatbots" or virtual assistants can answer patients' questions, provide information on treatments and medications and arrange appointments. This new revolution will bring patients closer to more personalised care and greater self-management and autonomy, the capabilities of which are still beyond our imagination. Examples of this can be found in clinical trials on pain management where the use of an artificial intelligence platform was comparable to the standard support patients received from a healthcare professional.93,94

The era of advanced therapies has coincided with the era of smartphones and being bombarded with information on websites, increasing the demand for healthcare which optimises instant communication and the delivery of quality information. As healthcare professionals, we have to ensure that this transition takes place and guide our patients towards a digital environment which is safe, makes their life easier and facilitates autonomous management of the disease. Making use of the new sources of artificial intelligence can ease the transition by lifting pressure from healthcare professionals and guaranteeing continuity of care for our patients.

Recommendations: consider functionality and ease of use when choosing an IBD app. GETECCU recommends the use of apps with content created by healthcare professionals and if language is a barrier, look for apps in Spanish for better accessibility.

Tele-educationDefinitionTele-education is the process of training or learning in a subject which is done through digital technologies and resources. In the context of IBD patients, it refers to using the internet to educate patients about their disease.

The need for tele-education in the patient with inflammatory bowel diseaseTele-education represents an opportunity to improve the main quality indicator of IBD care from the patient's perspective: the provision of information.70,95 These days, 50% of patients feel that their educational needs are not fully met, and 24% are very dissatisfied with the information they receive. In addition, a large majority (85%) expressed a desire for further training.96–98

According to a national survey, the medical team is identified as the main source of information (60%), followed by the Internet as the second choice; 80% of respondents use the Internet as a source of information, 30% of those on a regular basis (at least once a week).99 The Internet has established itself as the main source of information for children, young people, newly diagnosed patients and those with poorly controlled disease.99,100

Main advantages and disadvantages of tele-educationThe main advantage of tele-education is the accessibility of information without restrictions in terms of time or space, enabling patients to seek information before the consultation, ask questions in advance, and make better use of the time during the visit to consolidate their knowledge and strengthen the doctor-patient relationship.101 However, the main drawbacks are due to the quality of information on the internet, which can sometimes be outdated, confusing or difficult to verify and understand, and so cause uncertainty and anxiety.102,103 IBD units, aware of these risks, should recommend trusted digital resources, as patients highly value guidance on reliable digital information sources.99

Recommendation: to improve accessibility to quality information, it is recommended to promote the use of digital resources and tele-education, making it easier for patients to search for information prior to the consultation and prepare questions, thus optimising interaction time with the healthcare team.

Quality national educational websites to recommend to our patientsThe G-Educainflamatoria group, made up of healthcare professionals from GETECCU and the Grupo Enfermero de Trabajo en Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal [Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nursing Working Group], with the collaboration of patients with IBD and their association (Confederación de Asociaciones de Enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa de España; ACCU [Confederation of Spanish Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Patient Associations]), is working on the development of quality digital tools such as the G-Educainflamatoria website (educainflamatoria.com), aimed at offering educational support to these patients.104 This platform includes resources in a variety of formats, including themed videos (YouTube: GeducaEII), infographics, worksheets, booklets, prescription menus and a themed question forum, which are also shared on social media such as Twitter or X (@EntrenaEII), Facebook, Instagram and TikTok (EntrenaEII). Both patients and healthcare professionals value this tool for its quality and consider it a very useful and trusted resource in healthcare practice.99

Another Spanish national digital resource offering information and support for patients with IBD is the ACCU Spain website (accuesp.com), which includes a forum where users can share experiences and receive support.

Recommendation: GETECCU recommends using quality, up-to-date platforms and websites developed by healthcare professionals and recognised associations to ensure that patients receive verified and accurate information on IBD.

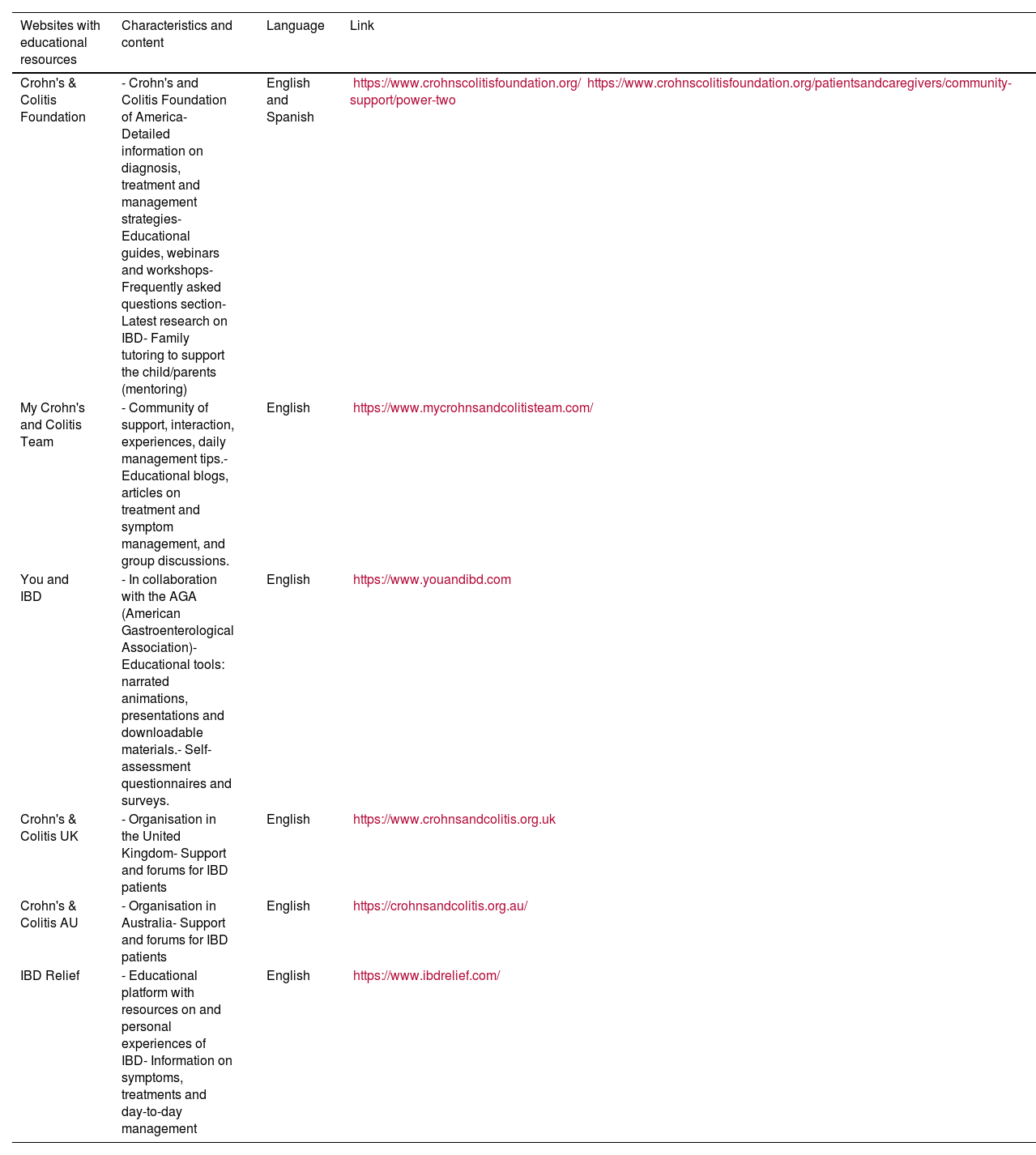

Other trusted digital educational resourcesThe main websites with trusted resources, mainly associated with medical organisations or patient foundations, are listed in Table 2. Some of these websites include forums where patients can share experiences and obtain information on treatment and management of the disease.

Websites with IBD educational resources and patient forums.

| Websites with educational resources | Characteristics and content | Language | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's & Colitis Foundation | - Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America- Detailed information on diagnosis, treatment and management strategies- Educational guides, webinars and workshops- Frequently asked questions section- Latest research on IBD- Family tutoring to support the child/parents (mentoring) | English and Spanish | https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/patientsandcaregivers/community-support/power-two |

| My Crohn's and Colitis Team | - Community of support, interaction, experiences, daily management tips.- Educational blogs, articles on treatment and symptom management, and group discussions. | English | https://www.mycrohnsandcolitisteam.com/ |

| You and IBD | - In collaboration with the AGA (American Gastroenterological Association)- Educational tools: narrated animations, presentations and downloadable materials.- Self-assessment questionnaires and surveys. | English | https://www.youandibd.com |

| Crohn's & Colitis UK | - Organisation in the United Kingdom- Support and forums for IBD patients | English | https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk |

| Crohn's & Colitis AU | - Organisation in Australia- Support and forums for IBD patients | English | https://crohnsandcolitis.org.au/ |

| IBD Relief | - Educational platform with resources on and personal experiences of IBD- Information on symptoms, treatments and day-to-day management | English | https://www.ibdrelief.com/ |

| Patient forums | Characteristics and contents | Language | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACCU Spain | - In Spain: space where users can share experiences and get support | Spanish | https://accuesp.com/ |

| Mayo Clinic Forum | - In the United States: space where users can share experiences and get support | English | https://connect.mayoclinic.org/ |

| Crohn's & Colitis Foundation | - In the United States: space where users can share experiences and get support | English | https://www.crohnscolitiscommunity.org/ |

| Crohn's & Colitis UK | - In the UK: space for users to share experiences and get support | English | https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk |

| IBD Support Group Forums | - International: space where users can share experiences and get support | English | https://www.ibdsupport.org/forums/ |

ACCU: Confederación de Asociaciones de Enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa de España [Confederation of Associations of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Patients of Spain]; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

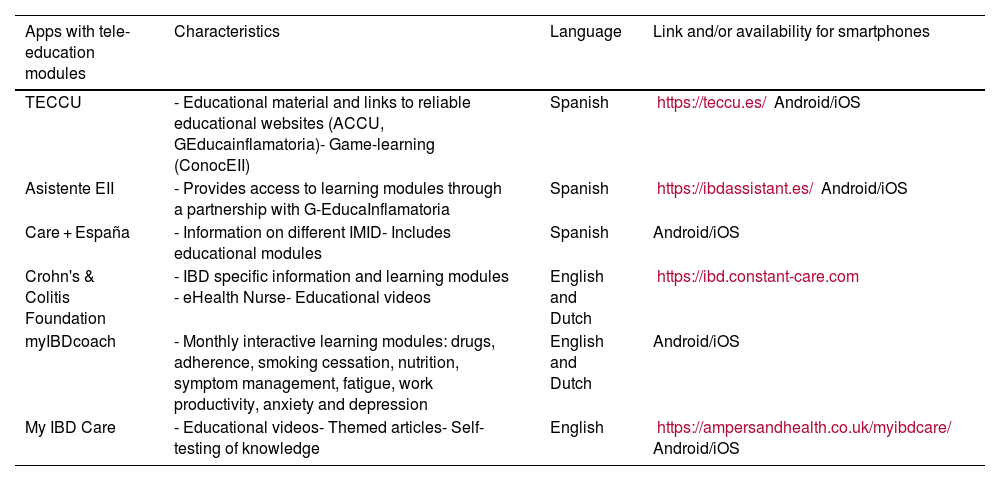

In addition, many of today's telemonitoring and follow-up applications incorporate their own educational modules or link to trusted educational websites (Table 3).85

Apps that include tele-education modules.

| Apps with tele-education modules | Characteristics | Language | Link and/or availability for smartphones |

|---|---|---|---|

| TECCU | - Educational material and links to reliable educational websites (ACCU, GEducainflamatoria)- Game-learning (ConocEII) | Spanish | https://teccu.es/ Android/iOS |

| Asistente EII | - Provides access to learning modules through a partnership with G-EducaInflamatoria | Spanish | https://ibdassistant.es/ Android/iOS |

| Care + España | - Information on different IMID- Includes educational modules | Spanish | Android/iOS |

| Crohn's & Colitis Foundation | - IBD specific information and learning modules - eHealth Nurse- Educational videos | English and Dutch | https://ibd.constant-care.com |

| myIBDcoach | - Monthly interactive learning modules: drugs, adherence, smoking cessation, nutrition, symptom management, fatigue, work productivity, anxiety and depression | English and Dutch | Android/iOS |

| My IBD Care | - Educational videos- Themed articles- Self-testing of knowledge | English | https://ampersandhealth.co.uk/myibdcare/ Android/iOS |

ACCU: Confederación de Asociaciones de Enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa de España [Confederation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations of Spain]; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IMID: immune-mediated inflammatory diseases; TECCU: telemedicina en la enfermedad de Crohn y la colitis ulcerosa [telemedicine in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis].

Recommendation: we recommend integrating tele-education into the care protocol of IBD units, ensuring that patients receive accurate and tailored information through telemonitoring tools, which include educational modules or links to reliable educational sources.

TelepharmacyDefinitionThe term telepharmacy is widely used both in Spain and internationally, although there is great variability in its definition, depending on its objectives, methods and applications. In its position statement, the Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria (SEFH) [Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy] defines telepharmacy as provision of pharmaceutical care at a distance through information and communication technologies.105 It includes activities such as treatment validation, pharmaceutical consultations, monitoring and coordination with other healthcare providers. The use of telepharmacy increased exponentially with the pandemic, showing benefits in health, satisfaction and efficiency.

How is telepharmacy carried out?In order to implement telepharmacy properly, the SEFH recommends the following105:

- a)

Procedures and quality: create standardised, integrated procedures in hospital pharmacy services, with approval and quality standards from the hospital centre or health authority.

- b)

Technology and training: ensure data privacy and security, adapt technologies, provide resources and train healthcare professionals and patients in the use of ICT.

- c)

Evaluation and indicators: use the digital medical records and establish indicators to monitor quality, satisfaction and outcomes.

- d)

Equity and regulation: ensure equitable access according to clinical need, with a legal framework that supports this practice and protects confidentiality.

As mentioned above, the implementation of telepharmacy programmes should not be restricted to disease or treatment, but should be based on the individual needs of patients. All patients with IBD are potential beneficiaries, depending on their particular situation and the resources available to them from their health centre.

IBD telepharmacy offers several key services106,107:

- a)

Pharmacotherapeutic monitoring: non-face-to-face assessment and monitoring, scheduled and agreed between the medical team, patient and/or caregiver, using synchronous (telephone consultations, video calls) and asynchronous (messaging) two-way communication.

- b)

Information and training: digital channels to educate patients, encourage learning and collect real-time data to personalise follow-up.

- c)

Multidisciplinary coordination: facilitates communication and recording of all relevant information in the shared medical records to coordinate treatments in different care settings.

- d)

Informed dispensing of medicines: enables the secure and scheduled remote delivery of medicines, with the following advantages:

- none-

Adherence to treatment: by enabling the delivery of medicines directly to the patient, telepharmacy minimises the need for frequent trips and waiting times and ensures that patients receive their medicines in optimal conditions and within the scheduled times. In addition, constant follow-up via teleconsultation helps remind the patient of the importance of taking their medication properly and on-time, thereby improving adherence.

- none-

Cost savings: remote dispensing reduces transport costs and consultation time for both the patient and the healthcare system. Patients enjoy financial savings by avoiding travel, while Hospital Pharmacy services can schedule deliveries and minimise on-demand consultations, optimising staff workload.

- none-

Recommendation: it is recommended to implement a telepharmacy programme for IBD patients, including virtual consultations and digital education, to optimise adherence and reduce travel and costs.

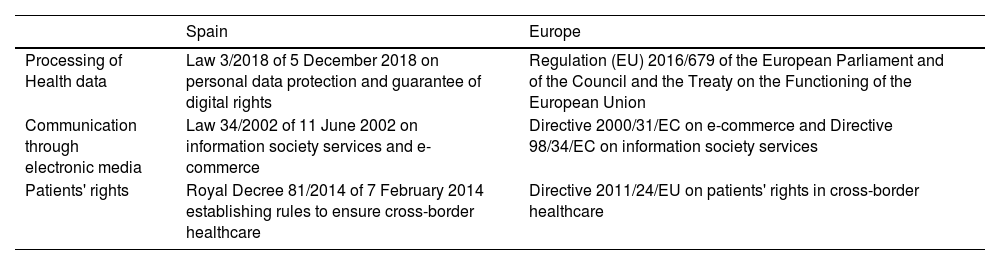

Legal and medical ethics aspects of the use of telemedicineAre there regulations for the use of telemedicine?In Spain, there are no specific regulations governing telemedicine, and the fact that health competences are devolved to the autonomous regions makes it difficult to create a specific regulatory framework for this. Moreover, in Europe, the digital agenda is being used to promote the spread of telemedicine in member countries108 (Table 4).

Summary of Spanish and European regulations on the use of Telemedicine.

| Spain | Europe | |

|---|---|---|

| Processing of Health data | Law 3/2018 of 5 December 2018 on personal data protection and guarantee of digital rights | Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union |

| Communication through electronic media | Law 34/2002 of 11 June 2002 on information society services and e-commerce | Directive 2000/31/EC on e-commerce and Directive 98/34/EC on information society services |

| Patients' rights | Royal Decree 81/2014 of 7 February 2014 establishing rules to ensure cross-border healthcare | Directive 2011/24/EU on patients' rights in cross-border healthcare |

EU: European Union.

Articles 103 and 104 of the Code of Medical Ethics underline the acceptance of the use of telemedicine in professional practice, provided that confidentiality and security of information is guaranteed. Furthermore, they stress that telemedicine should follow the same medical ethics standards that govern the doctor-patient relationship, with the commitment of the Colegio General de Consejos Oficiales de Médicos [General College of Medical Councils] to update these guidelines when necessary.109

The legal aspects of telemedicine focus on guaranteeing personal data protection and the confidentiality of medical information, while ensuring that the patient's rights are fully respected in this digital environment, following the regulations in force and the ethical principles governing the doctor-patient relationship.110

Specific recommendations for the use of telemedicineAs a consequence of the legal aspects (data protection and patient rights), below is a list of the principles to be taken into account in specific situations108,110:

- a)

Performing quality teleconsultation

In Spain, the recommendations for the use of teleconsultation are:

- 1

Identification: record the patient's name and surname (national identity card recommended in some cases); doctors must identify themselves with their name and registration number to ensure validity.

- 2

Informed consent: obtain specific consent for teleconsultation, explaining its scope and risks by means of an electronically or verbally signed form with a documentary record in the medical records.

- 3

Data protection: use secure platforms, complying with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which are approved for the healthcare sector and which comply with Spain's Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos y Garantía de los Derechos Digitales (LOPDGDD) [Organic Law on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights].

- 4

Clinical record: document the entire consultation in the patient's electronic medical records to ensure continuity of care and enable traceability.

- 5

Accessibility: inform the patient on how to access their data and contact details for future consultations.

- 1

- b)

Process for sending test results to the patient

- none-

Identification of the patient and healthcare personnel.

- none-

Protection of particularly sensitive health data, such as physical and mental health, sexuality, race, genetic code, family history, dietary habits and/or information related to alcohol or drug use.

- none-

The need for the patient's consent, with a prior, full and understandable explanation of the possible risks. Record this act in the medical records.

- none-

Ensure direct knowledge of the patient's medical history or access to it at the point of care through telemedicine tools.

- none-

Specify in writing in the medical records the telemedicine system used for the consultation, as well as the medical treatment prescribed and the recommendations given.

- none-

Use specialised telematic platforms, preferably corporate, for sending and receiving files between healthcare professionals and citizens which are secure, with personal identification code number systems or similar.

- none-

- c)

Privacy and confidentiality issues to consider

- none-

The right to privacy and one's own image, legally protected, includes the analytical data on the disease, and the patient's own image or the parts of their body affected by the disease they suffer from. This includes all healthcare personnel who, by reason of their profession and direct contact with the affected person, are aware of their situation and are directly or indirectly involved in the practices necessary to restore their health.

- none-

The assessment of patient images must be carried out in compliance with the principles of data processing: purpose limitation; data minimisation; accuracy; storage limitation; accountability; lawfulness, fairness and transparency; integrity and confidentiality.

- none-

To provide information on personal data protection, in particular access, rectification, erasure (right to be forgotten), opposition, portability, restriction of processing and right to object.

- none-

The act of sending or receiving diagnostic images does not require the patient's written informed consent, but does require that consent be obtained and recorded in the patient's medical record. In the case of teaching or scientific purposes, if the image allows the patient to be identified, it will also be necessary to obtain the patient's consent.

- none-

Recommendation: we recommend ensuring confidentiality and data protection for the use of telemedicine through proper identification and informed consent of the patient, and secure and approved platforms for the transmission of medical information.

Technical aspects of the use of telemedicineTechnical requirements for the use of telemedicineEffective implementation of telemedicine through teleconsultations, video calls or email consultations requires a robust technological infrastructure and ensuring the protection of patient information.111 The main technical requirements are detailed below:

- a)

Connectivity and bandwidth

The basis of any telemedicine service is a reliable, high-speed internet connection. This is essential to ensure the quality of video calls and the transmission of health data in real time.

- none-

Internet speed: a minimum speed of 10 Mbps for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads is recommended for high quality video conferencing.

- none-

Redundant networks: to avoid disruptions, it is advisable to have redundant networks and back-up systems in case of failure of the main connection.

- none-

- b)

Devices and hardware

Patients and healthcare providers must have appropriate devices to interact through the various forms of telemedicine.

- none-

Patient devices: patients need to have access to devices such as smartphones, tablets or computers with quality cameras and microphones.

- none-

Provider devices: providers need to have robust IT equipment, including high-resolution monitors, high-definition cameras and high-fidelity audio systems.

- c)

Software and platforms

The choice of software is crucial for the safety and effectiveness of teleconsultations. It must be secure, easy to use and compatible with a variety of devices.

- none-

Telemedicine platforms: applications and platforms specifically designed for virtual medical consultations, such as Doxy.me (Doxy.me, Inc., Charleston, South Carolina, USA), Zoom for Healthcare (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, California, USA) or Microsoft Teams Healthcare (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA).

- none-

Integration with electronic medical records: the software should be capable of integrating with electronic information systems to facilitate access and updating of patient medical records during and after consultations.

- none-

User-friendly interface: platforms should be intuitive for both patients and providers, with helpdesk functions available and multilingual support if needed.

- d)

Training and technical support

Education and ongoing support for both patient and provider are essential to ensure the effective use of telemedicine.

- none-

Patient education: clear instructions on how to access and use telemedicine services, including tutorials and ongoing technical support to resolve technical problems quickly and ensure continuity of service.

- none-

Provider training: training in the use of telemedicine platforms, digital data management and virtual communication skills.

Interoperability between HIS and the new forms of telemedicine is the main technological barrier to maximising the benefits of digital health technologies.

Interoperability enables different health systems and devices to communicate with each other, sharing data and working cohesively. In the context of telemedicine, this means that electronic medical records can be accessed during a virtual consultation, providing healthcare professionals with complete and up-to-date information about the patient. This not only improves diagnostic accuracy and treatment effectiveness, but also reduces duplication of tests and procedures, saving time and resources.

However, achieving a high level of interoperability is a major challenge. Differences between different systems in data standards, communication protocols and technological infrastructure can make integration difficult. It is crucial for the healthcare industry to adopt common standards and work towards creating a cohesive digital health ecosystem. Initiatives such as the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) are playing a vital role in this effort, providing a standard framework for the exchange of health data.112

Recommendation: for optimal use of telemedicine, we recommend secure platforms which can be integrated with electronic health records, allowing direct access and real-time updates.

Security regarding the use of telemedicineTelemedicine has transformed medical care, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this mode poses significant challenges in terms of digital security and information privacy. Data protection in the context of telemedicine is crucial to ensure patient confidence and the effectiveness of health services.

- a)

Personal data protection: the transmission of sensitive health information through digital platforms can be vulnerable to cyber-attacks. It is essential that data is end-to-end encrypted to prevent unauthorised access. Providers must use secure platforms which comply with regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe.111 It is important to use digital certificates and public key infrastructure to authenticate and guarantee the confidentiality of telemedicine communications.

- b)

Confidentiality in the home environment: many patients consult from home, where it can be difficult to ensure a private environment. This is of particular concern for vulnerable populations, such as people with mental illness or those living in shared spaces. Providers should offer guidance on how to find a private and safe space for consultations.113

In addition, it must be ensured that patients give their informed consent before using telemedicine services. This process should be clearly documented in the medical records and be part of the normal workflow, as discussed above.

- c)

Reliability of technology platforms: platforms used for telemedicine must be secure and easy to use for both patients and providers. During the pandemic, many providers had to adapt quickly to new technologies, sometimes resulting in the use of tools that were not secure or poorly integrated with HIS.

- d)

Awareness and education: both providers and patients need to be well informed about digital security best practices. This includes using strong passwords, regularly updating antivirus software and avoiding the use of public Wi-Fi networks to access telemedicine services.

Recommendation: we recommend ensuring security in telemedicine by using platforms with end-to-end encryption, ensuring confidentiality of personal data and guiding patients on how to maintain a private environment during consultations.

Security in the use of social mediaSocial media have transformed communication in healthcare, enabling a more dynamic interaction between patients and healthcare professionals. However, the security and privacy of these platforms are concerns which have to be considered.

Security risks- a)

Data privacy: social media collect and store large amounts of personal and health information. Lack of control over who can access this information can lead to privacy violations. A European study revealed that more than a quarter of health apps shared data with third parties without the user's knowledge.114

- b)

Confidentiality: the public nature of many social media platforms can compromise the confidentiality of medical information. Patients may inadvertently share sensitive details that could be exploited by third parties.

- c)

Cybersecurity: social media are a common target for cyber-attacks, including phishing and malware, which can compromise users' personal and professional information. The lack of robust security measures can facilitate such attacks.

- a)

Privacy control: social media platforms should offer robust privacy settings, enabling users to control who can see their information. It is essential that patients use such settings to protect their personal and health information.

- b)

Education and awareness: healthcare professionals should educate patients about the risks and best safety practices in the use of social media. This includes the importance of not sharing sensitive information publicly and recognising the signs of potential cybersecurity threats.

- c)

Regulations and standards: compliance with regulations such as the GDPR in Europe or the Portability Act is essential. These regulations oblige platforms to implement security measures to protect users' data.

Recommendations: we advise patients to exercise extreme caution on social media to avoid sharing sensitive medical information, by using privacy settings to protect their personal data.

ConclusionsTelemedicine has established itself as a key tool in the management of IBD, a chronic disease that requires constant monitoring to minimise complications and optimise treatment. This GETECCU position statement sets out recommendations on the implementation of different modes of telemedicine, such as teleconsultation, telemonitoring, mobile applications and telepharmacy, in the care of IBD patients.

Despite the advantages, the implementation of telemedicine is not without its challenges. The lack of specific regulations governing telemedicine in Spain, combined with decentralised competencies in health, raises legal and technical obstacles which need to be overcome. The implementation of telemedicine in IBD must be accompanied by rigorous security and data protection measures, with the use of platforms which comply with data protection regulations and enable integration with electronic medical records. Adequate informed consent and privacy-preserving guidance are essential to the trust in and success of telemedicine in this context.

In conclusion, telemedicine offers a promising solution for the management of IBD, improving accessibility and quality of care, and empowering patients in the management of their disease. However, to achieve proper implementation, technical, legal and capacity building challenges need to be addressed, and it has to be ensured that digital solutions are safely and effectively integrated into the healthcare system. This document lays the foundations for comprehensive, accessible and safe care for IBD patients, with the aim of optimising healthcare resources and improving patients' quality of life through innovative digital tools.

FundingNone.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.