Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) have a two-fold higher risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) than the general population, due to genetic, epigenetic and immunological factors, the carcinogenic effect induced by chronic mucosal inflammation, and other individual risk factors.1 Regarding sporadic CRC, CRC in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterised by earlier age at onset, with a higher rate of multiple neoplasm, in proximal location and with poorly differentiated lesions, which results in a lower overall survival rate.1

The objective of screening is to prevent CRC through early detection and resection of precursor lesions. Endoscopic surveillance has been shown to reduce the incidence of CRC, advanced and interval CRC, and the rates of colectomies and associated mortality.2 Although risk factors for CRC are well established, compliance with recommendations is suboptimal even in high-risk patients.1,3 It is therefore crucial to understand which patients should be screened, when screening should be started, how frequently follow-up colonoscopies should be performed, and what the best technique is for detecting dysplasia.

Who should have colorectal cancer screening?Patient selection should be based on the extension of the IBD. While in extensive UC and CD in the colon with involvement of more than 50%, the risk of CRC is four to six between times higher than in the general population, in left-sided UC and in colonic CD with involvement of less than 50%, the risk is low but still higher than in the general population. For this reason, CRC screening is recommended for all patients with left-sided or extensive UC or colonic CD or indeterminate colitis with involvement of more than one third of the colon. Screening is not recommended for patients with ulcerative proctitis, CD with involvement of less than one third of the colon, or with involvement exclusively of the upper or small intestine, except if associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).4,5

People with a pouch with ileoanal anastomosis have a very low risk of cancer in the pouch. However, a previous history of dysplasia or CRC, as well as the association with PSC, significantly increases this risk, so endoscopic surveillance is recommended in these cases. Patients with ileorectal anastomosis or ileostomy with excluded rectal stump have a relatively low incidence. However, with a risk six times higher than patients with ileoanal pouch, so endoscopic surveillance is also recommended for them.4,5

When should colorectal cancer screening begin?The risk of CRC increases with the duration of the disease, so it is recommended to start screening eight years after the onset of symptoms. PSC is associated with an increased risk of CRC nine times higher than the general population and 4–5 times higher than patients with IBD without PSC.4 Therefore, in patients with IBD and PSC, it is recommended to start screening when PSC is diagnosed, regardless of the activity, extent or duration of the IBD.4,5

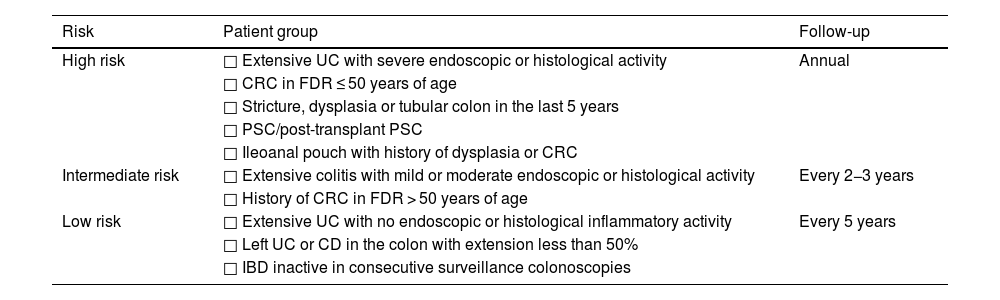

How often should follow-up colonoscopies be performed?Monitoring intervals are established based on the patient's updated risk factors. Thus, patients with extensive UC with severe activity in the last colonoscopy, history of CRC in a first-degree relative ≤ 50 years of age, history of stricture, dysplasia or tubular colon in an area affected by IBD in the last five years, presence of PSC or ileoanal pouch with a previous history of dysplasia or CRC, are considered high risk and must have annual endoscopic follow-up. Patients with extensive UC with moderate or mild activity or a history of CRC in a first-degree relative > 50 years of age are considered intermediate risk and should have endoscopic follow-up every two to three years. Pseudopolyps were traditionally considered to increase the risk of CRC, but more recent guidelines do not consider them as they probably reflect previous inflammation of the mucosa.4 Patients with left-sided UC or colonic CD with involvement of less than 50% and without intermediate or high risk factors should have endoscopic follow-up every five years. Patients with ileorectal anastomosis or excluded rectal stump should follow the same intervals as non-colectomised patients. Endoscopic follow-up should also take into account potential complications of colonoscopy, life expectancy and the patient's wishes (Table 1).4,5

Endoscopic follow-up intervals for screening for dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Risk | Patient group | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| High risk | □ Extensive UC with severe endoscopic or histological activity | Annual |

| □ CRC in FDR ≤ 50 years of age | ||

| □ Stricture, dysplasia or tubular colon in the last 5 years | ||

| □ PSC/post-transplant PSC | ||

| □ Ileoanal pouch with history of dysplasia or CRC | ||

| Intermediate risk | □ Extensive colitis with mild or moderate endoscopic or histological activity | Every 2−3 years |

| □ History of CRC in FDR > 50 years of age | ||

| Low risk | □ Extensive UC with no endoscopic or histological inflammatory activity | Every 5 years |

| □ Left UC or CD in the colon with extension less than 50% | ||

| □ IBD inactive in consecutive surveillance colonoscopies |

CRC: colorectal cancer; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; FDR: first-degree relatives.

The SCENIC (Surveillance for Colorectal Endoscopic Neoplasia Detection and Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: International Consensus Recommendations) consensus published in 2015,6 and updated in 2019,7 introduced a change in the surveillance strategy for dysplasia screening. It is recommended that screening be performed when IBD is in remission, as chronic inflammation can make it difficult to identify dysplasia, and with adequate bowel preparation for the detection of lesions.6

Classically, dysplasia screening was performed by taking random biopsies (four biopsies every 10 cm) and targeted biopsies of visible lesions, requiring approximately 30 biopsies from all segments of the colon to detect dysplasia with a probability of 90%. This is not a very cost-effective strategy and makes adherence difficult in day-to-day clinical practice. Random biopsies might presently be justified as an exception in high-risk patients, such as patients with PSC or tubular colon.8

The screening technique currently implemented is chromoendoscopy with directed biopsies. This is a diagnostic technique that facilitates the visualisation and characterisation of lesions, either by applying a dye through a diffusing catheter or washing pump (conventional chromoendoscopy), or by using light filters incorporated into the endoscope (virtual chromoendoscopy).9 The published studies (heterogeneous and including a small number of patients) conclude that conventional dye-based chromoendoscopy is superior to virtual chromoendoscopy, identifying a greater number of lesions (although no differences were found in the number of lesions with dysplasia detected), but with a longer procedure time. With the incorporation of high-definition endoscopes, both techniques (conventional dye-based and virtual chromoendoscopy) increase the yield for the detection of dysplasia in IBD.4,10

What should a screening colonoscopy report include?According to the recommendations of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] on dysplasia screening in patients with IBD, the report of a screening colonoscopy is considered of quality if it includes: 1) assessment of mucosal activity according to validated scales (UCEIS/Mayo/SES-CD); 2) assessment of colonic cleanliness using an objective scale (Boston scale by sections); 3) presence or absence of pseudopolyps (indicating whether screening is possible or not for the presence of pseudopolyps, with careful assessment of the mucosa between them)11; 4) morphology of the lesions according to the modified Paris classification, description of the edges, and presence or absence of ulceration; 5) crypt pattern of the lesions (Kudo classification for dye chromoendoscopy, NICE or Sano classification for virtual chromoendoscopy with narrow band imaging); 6) photodocumentation of the lesions; and 7) description of the resectability of the lesions and, in the case of resection, include the resection method used.12

What is the approach for detection of dysplasia?When dysplasia is found in an area affected by IBD, management should be multidisciplinary, including an IBD specialist, endoscopist and a colorectal surgeon, and the finding of dysplasia should have been confirmed by two expert pathologists.13 Currently, most lesions with dysplasia are visible, small (<20 mm) and can be resected endoscopically with standard polypectomy techniques, reserving surgery only for exceptional cases of non-resectable lesions.14 In expert centres, it is also possible to resect some lesions by endoscopic submucosal dissection.4 Previously, the management of lesions with dysplasia was primarily surgical, with a high rate of colectomies.4,15 With the advances in surgical techniques, radical surgery with ileostomy has been relegated to the background, and other techniques, such as ileal pouch or segmental colectomies, have been developed, improving patient quality of life.

After resection of a lesion with visible dysplasia, the SCENIC consensus also recommends surveillance with chromoendoscopy as opposed to colectomy.6 It defines that a lesion is endoscopically resectable if it has a defined margin and if the polypectomy has been complete (which is subsequently confirmed in the histological analysis). In cases of dysplasia identified with random biopsies, in addition to the finding being confirmed by two pathologists, screening colonoscopy with dye-based chromoendoscopy by an experienced endoscopist should be repeated. If a visible lesion is identified, the usual resection techniques will be used. If findings of invisible dysplasia persist, if the dysplasia is low-grade, close screening (every six months the first year) using chromoendoscopy could be considered, and if it is high-grade, colectomy could be considered. If changes are found but are not definite for dysplasia, medical treatment should be optimised if there is IBD activity, repeat chromoendoscopy with biopsies, and consider annual endoscopic follow-up. If the dysplasia is multifocal, surgery is generally recommended, except for selected cases of lesions resected en bloc in expert centres where endoscopic follow-up could be considered. Finally, the finding of dysplasia in an area not affected by IBD should be treated and followed up according to the recommendations for the general population.4,13,16

FundingMaria Pilar Ballester receives funding through a Juan Rodes contract (JR23/00,029) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute]. Cristina Rubín de Célix has received funding for training from Ferring, Tillotts Pharma, AbbVie, Sandoz, Alfasigma, Lilly, Norgine, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda and Janssen. The funding entities did not participate in the preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsNot applicable.

María Pilar Ballester, Cristina Rubin de Célix, Lucía Madero, Margalida Calafat, Iria Baston-Rey and Eduard Brunet-Mas have no conflicts of interest for the article.