There is increasing evidence that proactive monitoring is useful in improving the control of inflammatory bowel disease, although it remains controversial. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of proactive TDM based on the Bayesian approach to optimise the IFX dose compared with the standard of care dosing in patients with IBD.

MethodsRetrospective observational cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients>18 years. Patients were classified into two groups according to the strategy used to optimise the dose of IFX: a standard therapy group (ST-group) with clinically based dose adjustment and therapeutic drug monitoring group (TDM-group), with estimation of pharmacokinetic parameters calculated by Bayesian prediction.

ResultsA total of 153 patients were included. Of these, 75 were in the TDM-group. Clinical response at week 52 was evaluated in 114 patients. The proportion of patients who achieved clinical remission was higher in the TDM than in the ST-group (80.7% vs 61.4%, respectively, p=0.023). A total of 28 patients (24.6%) met the parameters for the composite variable ‘poor clinical outcome’ at week 52. The proportion of patients who reached this outcome was lower in the TDM-group than in the ST-group (12.3% vs 36.8%, respectively, p=0.002).

ConclusionsProactive therapeutic drug monitoring using Bayesian approach is associated with higher secondary response and fewer long-term complications.

Cada vez hay más evidencia de que la monitorización proactiva es útil para mejorar el control de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), aunque sigue siendo controvertida. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la eficacia de la monitorización de fármacos terapéuticos (TDM) proactiva basada en el enfoque bayesiano en comparación con el manejo estándar en pacientes con EII.

MétodosCohorte observacional retrospectiva de pacientes con EEI > 18 años. Los pacientes se clasificaron en dos grupos de acuerdo con la estrategia utilizada para optimizar la dosis de infliximab (IFX): un grupo de terapia estándar (grupo-ST) con ajuste de dosis basado en la clínica y un grupo de monitorización terapéutica del fármaco (grupo-TDM), con estimación de parámetros farmacocinéticos calculados mediante estimación bayesiana.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 153 pacientes. De estos, 75 estaban en el grupo-TDM. La respuesta clínica en la semana 52 se evaluó en 114 pacientes. La proporción de pacientes que alcanzaron la remisión clínica fue mayor en el grupo-TDM que en el grupo-ST (80,7 vs. 61,4%, respectivamente, p = 0,023). Un total de 28 pacientes (24,6%) cumplieron los parámetros de la variable compuesta «resultado clínico deficiente» en la semana 52. La proporción de pacientes que alcanzaron este resultado fue menor en el grupo-TDM que en el grupo-ST (12,3 vs. 36,8%, respectivamente, p = 0,002).

ConclusionesLa TDM proactiva mediante el enfoque bayesiano se asocia con una mayor respuesta secundaria y menos complicaciones a largo plazo.

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are two chronic immune-mediated inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) with variable courses.1 The effectiveness of infliximab, the first anti-TNFα (tumour necrosis factor alpha) drug approved for the treatment of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), has been demonstrated.2–4 However, 10–40% of patients are primary non-responders, and 20–40% suffer a secondary loss of response (in the maintenance phase) over time, especially during the first year.5–7

Numerous studies suggest a positive association between trough levels of anti-TNF drugs and increased rates of response to treatment; reduced relapse, hospitalisations and surgeries; and improved quality of life of patients with IBD.8 The multicentre, prospective PANTs study showed that the main factor independently associated with primary non-response was low infliximab concentration at weeks 14 and 54.9

Many studies have shown high inter-individual variability in serum infliximab concentrations.10,11 Factors that can lead to low infliximab exposure include high inflammatory burden with high CRP, faecal calprotectin, low albumin and haemoglobin. Other parameters related to increased clearance are body weight, previous exposure to anti-TNF drugs and development of immunogenicity. Early identification of patients with low anti-TNF levels and the presence of immunogenicity may help to predict patients at greater risk for treatment failure.9 Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), defined as the assessment of drug concentrations and antidrug antibodies,5 is a tool that allows for the individual optimisation of dosage regimens of drugs with high inter-individual variability, to ensure adequate exposure to the drug.12,13 TDM is considered reactive when there are signs or symptoms of disease activity, and proactive when it takes the form of periodic monitoring of patients responding to TNF antagonist therapy to allow optimisation of treatment by dose adjustment to a target drug concentration.5

Reactive TDM is widely accepted,14 while the positioning of the proactive strategy in the clinical guidelines of the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) 15 and American College of Gastroenterology (AGA) 16 is not routinely recommended. The recommendations in these guidelines are primarily based on two prospective clinical trials, TAXIT 13 and TAILORIX 17. These studies failed to meet their primary endpoints, probably due to some methodological issues in the study designs. In contrast, various expert panels 5,16,18 have proposed that proactive TDM can be considered in certain scenarios, such as in the induction period, during the first year of maintenance therapy, for optimising infliximab monotherapy as an alternative to combination therapy with an immunosuppressive 14 and after the initial dose after a drug holidays.

We consider it important to emphasise that most of the studies aimed at demonstrating the usefulness of TDM use dosing strategies based on algorithms, and few studies are based on the use of population pharmacokinetic models for dose individualisation.19 A Bayesian approach allows for the estimation of individual pharmacokinetic parameters, and could be a useful method to estimate serum concentrations of different doses for a given patient. For this reason, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of proactive TDM based on the Bayesian approach to optimise the IFX dose compared with the standard of care dosing in patients with IBD.

MethodsStudy design and patient cohortA retrospective observational cohort of consecutive IBD patients study was performed at a single centre in a regional reference hospital in Murcia, south-eastern Spain. Adult patients (> 18 years) with CD and UC who started IFX treatment between December 2007 and September 2020 were included in the study. Consecutive patients who successfully completed IFX induction therapy (5mg/kg on weeks 0, 2, and 6) were included. Patients were followed up until 52 weeks of treatment, or until infliximab discontinuation if it occurred before 52 weeks. The main exclusion criteria were insufficient data and follow-up at other centres. The study was approved by the local ethical research committee.

Patients were classified into two groups according to the strategy used to optimise the dose of IFX during the follow-up period: a standard therapy group (ST-group) and a therapeutic drug monitoring group (TDM-group). From December 2007 to December 2017, the dosing strategy was based on clinical data without TDM dose adjustment (ST-group). Therapeutic decisions were made at each physician's discretion and were reflective of real-life clinical practice. From January 2018 to September 2020, the strategy to optimise the dose was based on TDM (TDM-group). In this group, the IFX trough levels (ITL) were determined at any time during the follow-up period (induction or maintenance). ITL≥15μg/mL in the induction period (week 6), and ITL≥3μg/mL for CD and ≥5μg/mL for UC, in the maintenance period, were considered as the optimal cut-off values.19 In patients with an ITL at week 6 below the optimal therapeutic range, the dose adjustment was performed at first maintenance dose. The individual pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by Bayesian prediction for each patient, and were used to estimate the predicted ITL achieved in different dosing regimens. Bayesian prediction was performed using NONMEM software version 7.3 based on the population pharmacokinetic model developed by Fasanmade et al.10

Data collectionThe following demographic and clinical data were recorded: sex, age, diagnosis, disease behaviour and location according to the Montreal Classification at diagnosis,20 perianal disease, time to start IFX therapy, previous biological and steroidal therapy and the use of concomitant immunosuppressive therapy.

ITLs were determined from serum samples collected prior to IFX infusion. The data about serum drug concentration and the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters of each patient were obtained from a local database of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics Unit (Department of Pharmacy). Serum ITL and antibodies to infliximab (ATI) were measured using an available validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (PromonitorR; Grifols, Spain). This method did not allow for the detection of ATIs in the presence of infliximab (drug-sensitive assay).

EndpointsDisease activity was evaluated retrospectively by recollection of clinical criteria from the electronic patient charts. The primary endpoint of the study was defined as the proportion of patients in each group in clinical remission at week 52. Clinical remission was defined as a Harvey-Bradshaw (HBI) score<4 for CD, and a Mayo score<2 for UC. In addition, the composite variable ‘poor clinical outcomes’ (severe flare, hospitalisation or surgery IBD-related) was also evaluated during the follow-up period.

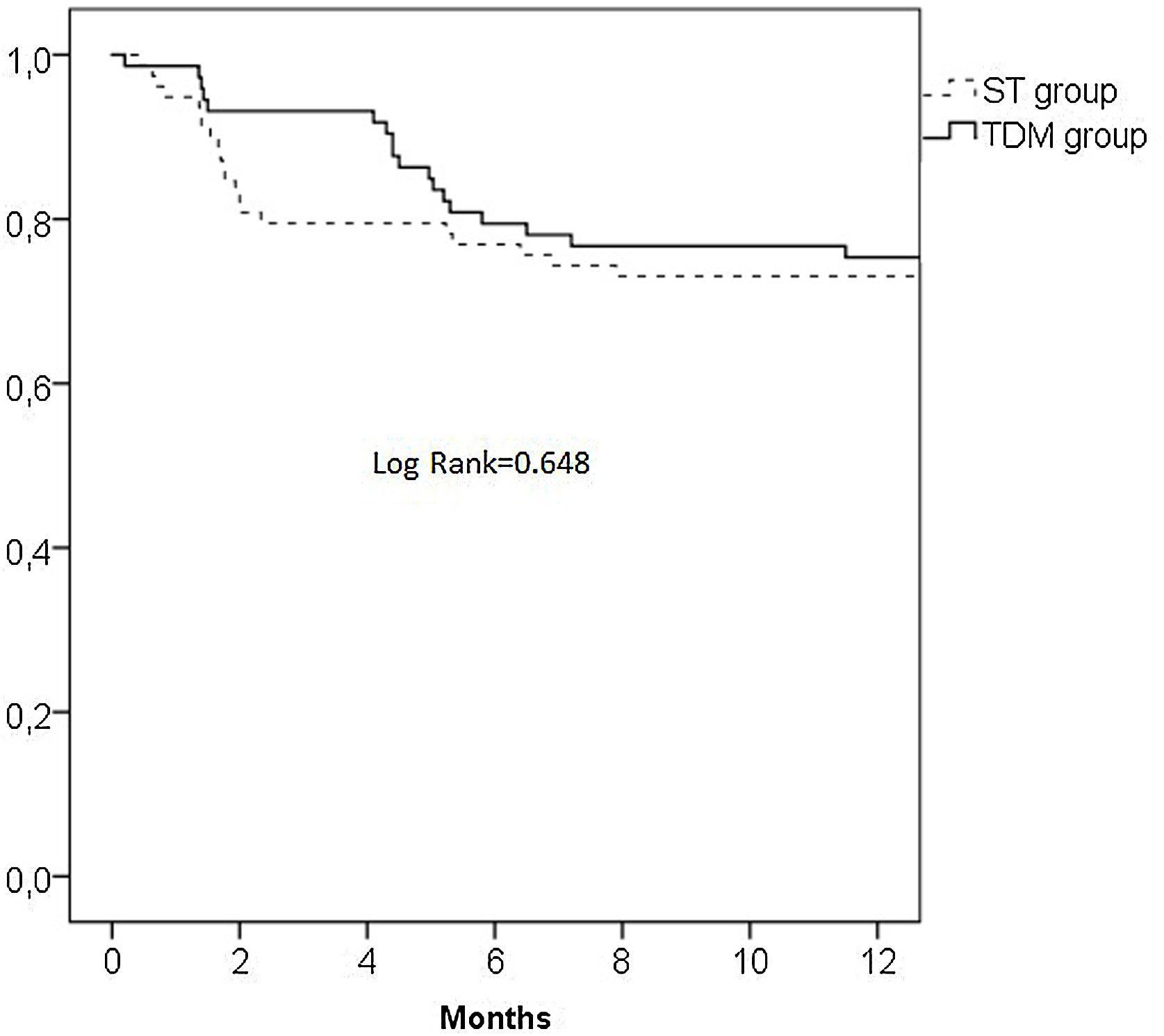

The retention rate (drug survival) of the IFX treatment in both groups (time interval between initiation and discontinuation therapy) was determined, and the reasons for discontinuation of treatment were described.

Statistical analysisCategorical data were shown as absolute numbers and percentages, whereas continuous variables were expressed as median values and measures of variability as interquartile ranges (IQR). Continuous variables were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test and categorical variables were analysed using the Fisher's exact test. The Kaplan–Meier estimator was used to generate survival curves for infliximab treatment according to dosing strategy. The log-rank test was used to compare overall survival curves for the TDM and ST-group. The proportions of patients with clinical remission and poor clinical outcomes in the TDM and ST-groups were compared using the χ2 test. Univariate regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with achieving clinical remission and poor clinical outcomes. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

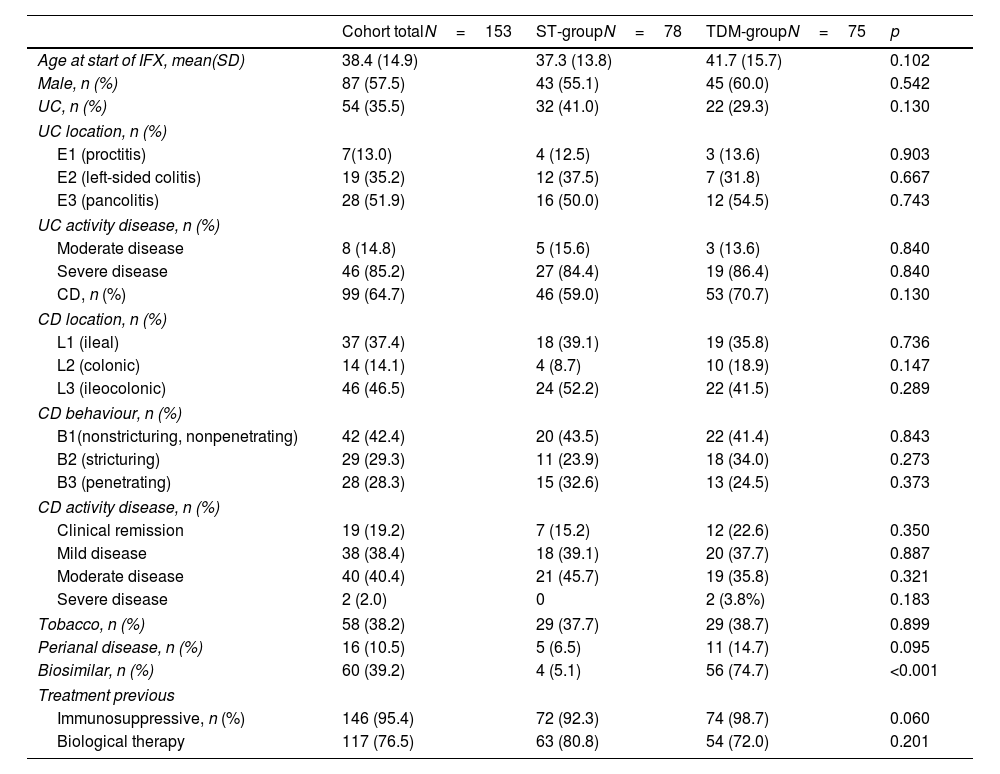

ResultsThe study population consisted of 153 patients, 57.5% of whom were male, with a median age at start of IFX of 34.8 (14.9) years. The TDM-group included 75 (49%) patients and ST-group included 78 (51.0%) patients. Ninety-nine patients (64.7%) had CD, and 54 (35.5%) had UC. In the case of UC, the disease was most frequently pancolitic (51.9%) and in the case of CD, it was ileocolonic (46.5%). At baseline, 31.4% of patients had severe disease (28.0% TDM vs 34.6% ST, p=0.378). Significant differences were found in the use of the biosimilar infliximab (92.5% TDM vs 20.4% ST, p<0.001). The baseline demographics of the study population are summarised in Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline.

| Cohort totalN=153 | ST-groupN=78 | TDM-groupN=75 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start of IFX, mean(SD) | 38.4 (14.9) | 37.3 (13.8) | 41.7 (15.7) | 0.102 |

| Male, n (%) | 87 (57.5) | 43 (55.1) | 45 (60.0) | 0.542 |

| UC, n (%) | 54 (35.5) | 32 (41.0) | 22 (29.3) | 0.130 |

| UC location, n (%) | ||||

| E1 (proctitis) | 7(13.0) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (13.6) | 0.903 |

| E2 (left-sided colitis) | 19 (35.2) | 12 (37.5) | 7 (31.8) | 0.667 |

| E3 (pancolitis) | 28 (51.9) | 16 (50.0) | 12 (54.5) | 0.743 |

| UC activity disease, n (%) | ||||

| Moderate disease | 8 (14.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (13.6) | 0.840 |

| Severe disease | 46 (85.2) | 27 (84.4) | 19 (86.4) | 0.840 |

| CD, n (%) | 99 (64.7) | 46 (59.0) | 53 (70.7) | 0.130 |

| CD location, n (%) | ||||

| L1 (ileal) | 37 (37.4) | 18 (39.1) | 19 (35.8) | 0.736 |

| L2 (colonic) | 14 (14.1) | 4 (8.7) | 10 (18.9) | 0.147 |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 46 (46.5) | 24 (52.2) | 22 (41.5) | 0.289 |

| CD behaviour, n (%) | ||||

| B1(nonstricturing, nonpenetrating) | 42 (42.4) | 20 (43.5) | 22 (41.4) | 0.843 |

| B2 (stricturing) | 29 (29.3) | 11 (23.9) | 18 (34.0) | 0.273 |

| B3 (penetrating) | 28 (28.3) | 15 (32.6) | 13 (24.5) | 0.373 |

| CD activity disease, n (%) | ||||

| Clinical remission | 19 (19.2) | 7 (15.2) | 12 (22.6) | 0.350 |

| Mild disease | 38 (38.4) | 18 (39.1) | 20 (37.7) | 0.887 |

| Moderate disease | 40 (40.4) | 21 (45.7) | 19 (35.8) | 0.321 |

| Severe disease | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (3.8%) | 0.183 |

| Tobacco, n (%) | 58 (38.2) | 29 (37.7) | 29 (38.7) | 0.899 |

| Perianal disease, n (%) | 16 (10.5) | 5 (6.5) | 11 (14.7) | 0.095 |

| Biosimilar, n (%) | 60 (39.2) | 4 (5.1) | 56 (74.7) | <0.001 |

| Treatment previous | ||||

| Immunosuppressive, n (%) | 146 (95.4) | 72 (92.3) | 74 (98.7) | 0.060 |

| Biological therapy | 117 (76.5) | 63 (80.8) | 54 (72.0) | 0.201 |

CD: Crohn's disease; IFX: infliximab; SD: standard deviation; ST: standard therapy; TDM: therapeutic drug monitoring; UC: ulcerative colitis

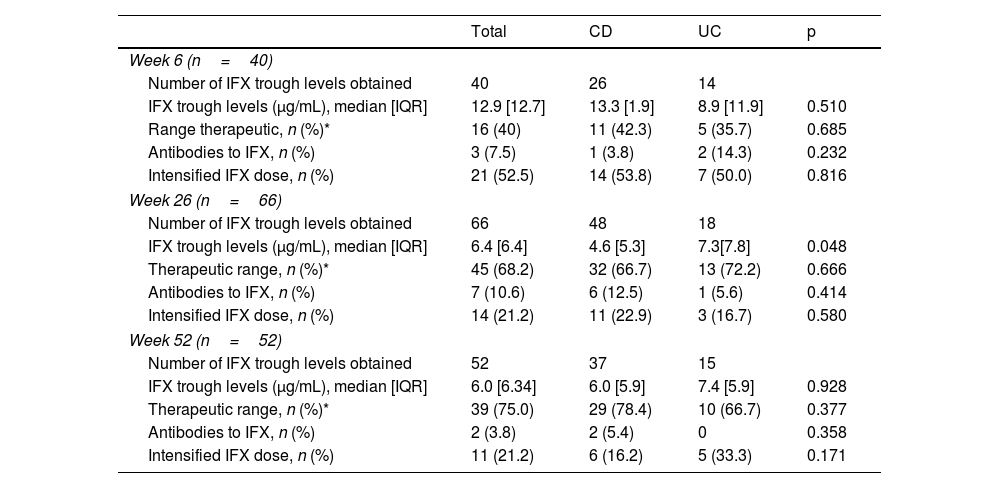

A total of 158 measurements were available for the TDM-group. Of these, 40 (25.3%) were obtained at week 6 of the induction period, 66 (41.8%) at week 26 and 52 (32.9%) at week 52. The mean number of ITL measurements per patient at week 6, 26 and 52 was 0.53, 0.94 and 0.87, respectively. Median ITLs at weeks 6, 26 and 52 were 12.9μg/mL, 6.4μg/mL and 6.0μg/mL, respectively. The proportion of patients with ITL in therapeutic range at week 6 (ITL ≥15μg/mL) was 40%, while eight (20%) patients had ITL <5μg/mL. Neutralising anti-IFX antibodies were detected in three patients. The proportion of patients with ITL in therapeutic ranges at weeks 26 and 52 was 68.2% and 75.0%, respectively, and immunogenicity was detected at weeks 26 and 52 in 10.6% and 3.8% patients, respectively (Table 2).

Characteristics of infliximab trough concentration among patients in the TDM group.

| Total | CD | UC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 6 (n=40) | ||||

| Number of IFX trough levels obtained | 40 | 26 | 14 | |

| IFX trough levels (μg/mL), median [IQR] | 12.9 [12.7] | 13.3 [1.9] | 8.9 [11.9] | 0.510 |

| Range therapeutic, n (%)* | 16 (40) | 11 (42.3) | 5 (35.7) | 0.685 |

| Antibodies to IFX, n (%) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (14.3) | 0.232 |

| Intensified IFX dose, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 14 (53.8) | 7 (50.0) | 0.816 |

| Week 26 (n=66) | ||||

| Number of IFX trough levels obtained | 66 | 48 | 18 | |

| IFX trough levels (μg/mL), median [IQR] | 6.4 [6.4] | 4.6 [5.3] | 7.3[7.8] | 0.048 |

| Therapeutic range, n (%)* | 45 (68.2) | 32 (66.7) | 13 (72.2) | 0.666 |

| Antibodies to IFX, n (%) | 7 (10.6) | 6 (12.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0.414 |

| Intensified IFX dose, n (%) | 14 (21.2) | 11 (22.9) | 3 (16.7) | 0.580 |

| Week 52 (n=52) | ||||

| Number of IFX trough levels obtained | 52 | 37 | 15 | |

| IFX trough levels (μg/mL), median [IQR] | 6.0 [6.34] | 6.0 [5.9] | 7.4 [5.9] | 0.928 |

| Therapeutic range, n (%)* | 39 (75.0) | 29 (78.4) | 10 (66.7) | 0.377 |

| Antibodies to IFX, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (5.4) | 0 | 0.358 |

| Intensified IFX dose, n (%) | 11 (21.2) | 6 (16.2) | 5 (33.3) | 0.171 |

Half, or 80 (52.3%), of the patients received intensified therapy during the study period (49.3% TDM vs 55.1% ST, p=0.473). In the TDM-group, the dose was intensified following the proactive strategy. In all patients with subtherapeutic ITL without anti-IFX antibodies, the dose was intensified. In one patient with undetectable ITL and low anti-IFX antibodies titre (20.6AU/mL), the interval was shortened to 5mg/kg every four weeks and methotrexate was added. The most frequent intensification dose regimen performed consisted of interval reduction in infliximab administration at 5mg/kg every six weeks (28.0% TDM vs 41.0% ST, p=0.091) and 5mg/kg every four weeks (18.7% TDM vs 12.8% ST, p=0.320).

Infliximab treatment withdrawalThe median follow-up time was 39 weeks, and no differences were found between the TDM and ST-group (40.6 weeks vs 38.7 weeks, p=0.589). Treatment withdrawal occurred in 39 (25.5%) patients, and no differences was found between TDM and ST-group (24.0% vs 26.9%, respectively, p=0.678). The reasons for treatment withdrawal were classified into five categories: lost response (13 patients; 8 ST and 5 TDM-group), side effects (13 patients; 10 ST and 3 TDM-group), immunogenicity (9 patients from the TDM-group), pregnancy (1 from the TDM-group) and loss to follow-up (3 patients from the ST-group). The adverse effects observed were infusion reaction, infections, dermatological causes and arthralgia.

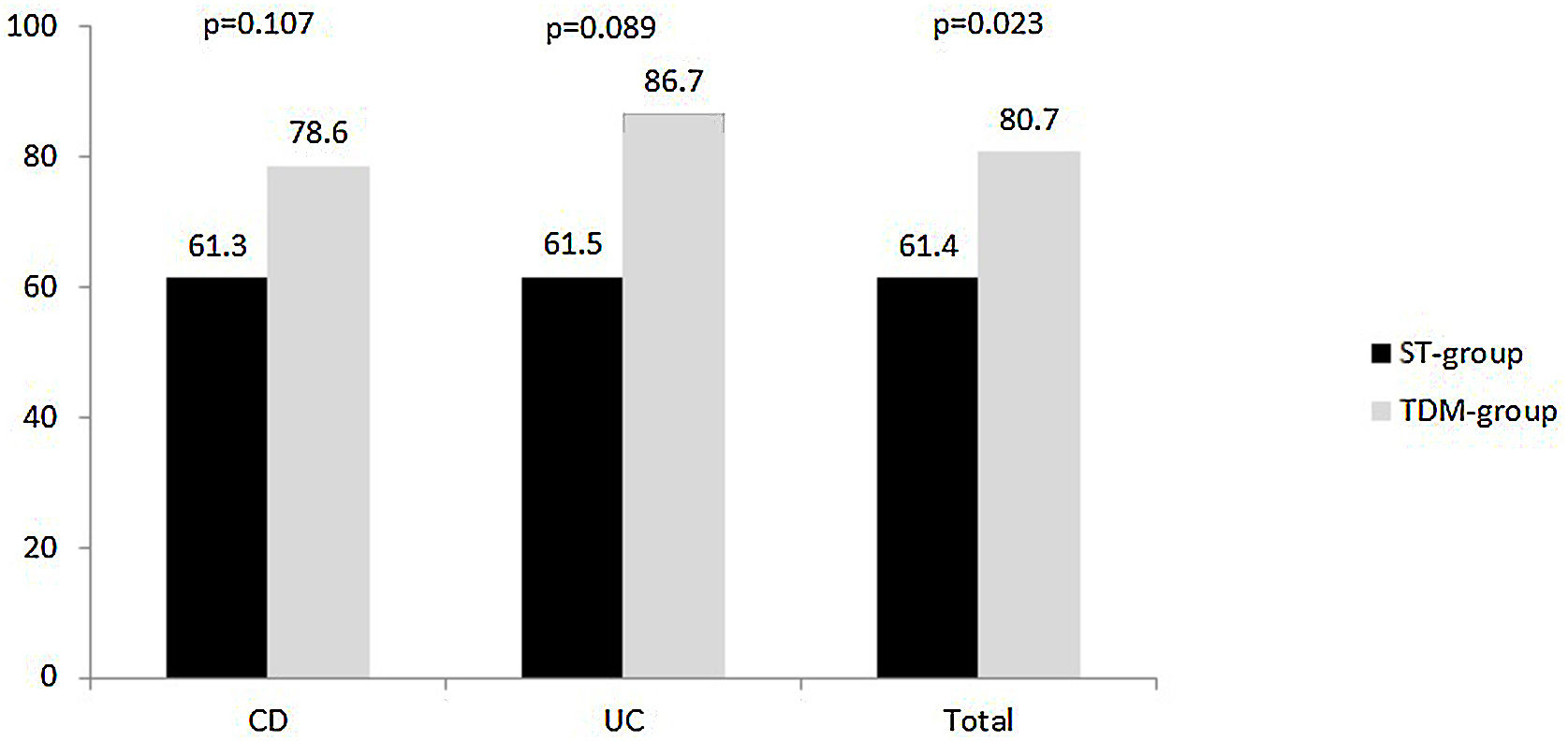

Clinical remission and poor clinical outcomesClinical response at week 52 was evaluated in 114 patients. The proportion of patients who achieved clinical remission was 71.1% (81/114), and it was observed that it was higher in the TDM than in the ST-group (80.7% vs 61.4%, respectively, p=0.023). This trend was maintained when the analysis was performed by diagnosis, but statistical significance was not reached in patients with CD or with UC (Fig. 1).

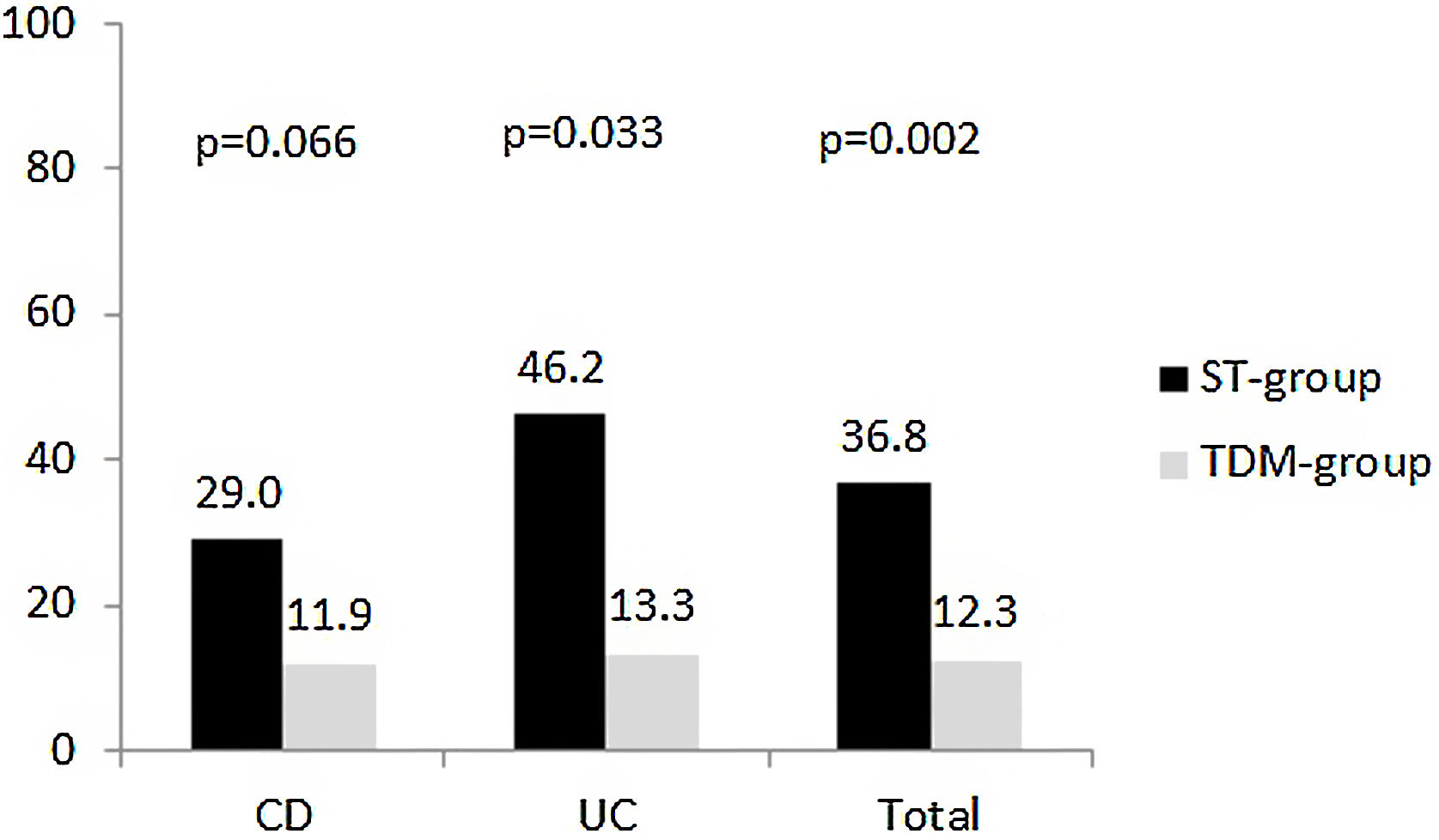

At week 52, 28 patients met the parameters for the composite variable ‘poor clinical outcome’ was reached in (24.6%). The proportion of patients was lower in the TDM-group than ST-group (12.3% vs 36.8%, respectively, p=0.002) (Fig. 2). No statistically significant differences were observed by diagnosis, but the trend was maintained. However, when each of the variables that made up the composite variable was analysed separately, a significant difference was observed in the proportion of patients who suffered at least one flare (8.8% TDM vs 31.6% ST, p=0.02). There are statistically significant differences were found for hospitalisations (8.8% TDM vs 31.6% ST, p=0.02). Only three patients in the ST-group were hospitalised during the study period, and one of them underwent surgery.

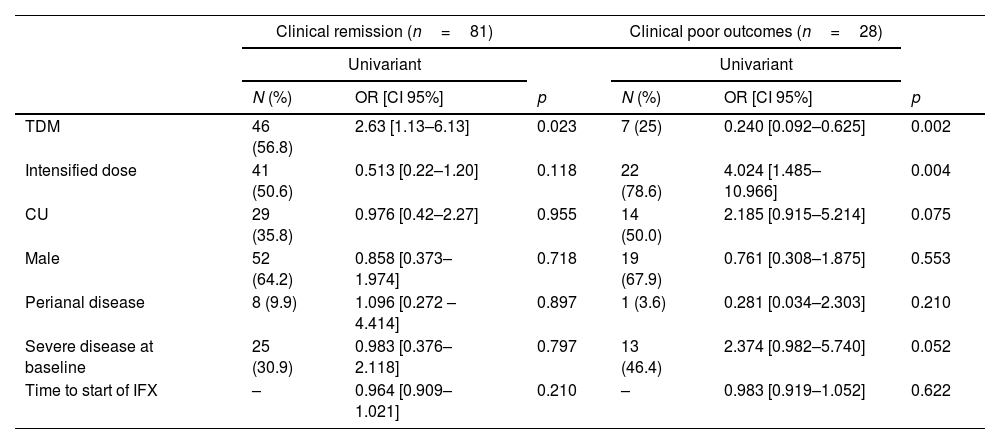

Predictors of clinical outcomesThe results of the univariate analysis showed that the only factor associated with achieving clinical remission at week 52 was TDM strategy (OR: 2.6 [95% CI: 1.1–6.1]). For the composite variable ‘clinical poor outcomes’, an association was observed with TDM strategy (OR: 0.2 [95% CI: 0.01–0.6) and dose intensification (OR: 4.0 [95% CI: 1.5–11.0]). These results are shown in Table 3.

Predictors of clinical outcomes at week 52.

| Clinical remission (n=81) | Clinical poor outcomes (n=28) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariant | Univariant | |||||

| N (%) | OR [CI 95%] | p | N (%) | OR [CI 95%] | p | |

| TDM | 46 (56.8) | 2.63 [1.13–6.13] | 0.023 | 7 (25) | 0.240 [0.092–0.625] | 0.002 |

| Intensified dose | 41 (50.6) | 0.513 [0.22–1.20] | 0.118 | 22 (78.6) | 4.024 [1.485–10.966] | 0.004 |

| CU | 29 (35.8) | 0.976 [0.42–2.27] | 0.955 | 14 (50.0) | 2.185 [0.915–5.214] | 0.075 |

| Male | 52 (64.2) | 0.858 [0.373–1.974] | 0.718 | 19 (67.9) | 0.761 [0.308–1.875] | 0.553 |

| Perianal disease | 8 (9.9) | 1.096 [0.272 –4.414] | 0.897 | 1 (3.6) | 0.281 [0.034–2.303] | 0.210 |

| Severe disease at baseline | 25 (30.9) | 0.983 [0.376–2.118] | 0.797 | 13 (46.4) | 2.374 [0.982–5.740] | 0.052 |

| Time to start of IFX | – | 0.964 [0.909–1.021] | 0.210 | – | 0.983 [0.919–1.052] | 0.622 |

In the subgroup analysis, it was observed that of a total of 81 patients who achieved clinical remission, 41 (50.6%) patients received an intensified regimen. Of these, 56.1% were in the TDM-group and the remaining 43.9% in the ST-group (p=0.066). For the composite variable, it was observed that of the 28 patients with poor clinical outcomes, 22 (78.6%) received an intensified regimen. Of these, 72.7% were in the ST-group and the remaining 27.3% in the TDM-group (p=0.018).

DiscussionThe clinical role of TDM of biological drugs used for immune-mediated inflammatory disorders is still debated. Currently, implementation is based on clinical experience and observational studies, since only a few clinical trials have been conducted.13,17,21 In this retrospective cohort study conducted in patients with IBD, we compared the clinical response achieved in maintenance phase according to two IFX dosing strategies. In our study, it was observed that the proportion of patients who achieved clinical remission at week 52 was higher in the TDM-group, with better clinical outcomes.

Our results agree with previous studies. The prospective PANTS (Personalising anti-TNF therapy in CD),9 showed that low IFX concentration at week 14 was independently associated with non-remission at week 52. Papamicheel et al.22 and Vande Casteele et al.13 have shown that proactive IFX optimisation to achieve a threshold drug concentration during maintenance therapy is associated with better long-term outcomes, including longer drug persistence. reduced risk of relapse and fewer hospitalisations and surgeries, than empiric dose escalation and/or reactive TDM.

Observational studies support the idea that proactive TDM strategy achieves better control of the disease. RCTs to test proactive TDM are more limited, demonstrating inconsistent results, probably also because of differences in study design and methodological issues. The landmark randomised controlled trial TAXIT,13 despite failing to meet its primary endpoint probably due to methodological issues in the study design (only one year of follow-up, delayed optimisation until next dose, optimising all patients prior to randomisation),23 showed that proactive TDM of infliximab compared with clinically based dosing was associated with lower frequency of undetectable drug concentrations and lower risk of relapse. In a multicentre prospective randomised trial, the TAILORIX study,17 it was demonstrated that increasing the IFX dose due to a combination of symptoms, biomarkers, and/or TDM did not lead to corticosteroid-free clinical remission at week 54 compared to the management of symptoms alone. However, we emphasise that dose escalation was not solely based on ITL, but also on symptoms and biomarkers. In fact, only a minority of the patients in the ‘optimised groups’ had doses escalated based on trough concentrations, and <50% of the ‘optimized’ groups achieved a sustained infliximab concentration>3μg/ml, which was even less than the control group (60%).

The NOR-DRUM study comprised 2 trials enrolling patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases requiring treatment with IFX.24,25 It aimed to compare proactive TDM with standard in both the induction (NOR-DRUM A) and maintenance phases (NOR-DRUM B). The outcome of NOR-DRUM A, remission at week 30, showed no benefit of a proactive TDM approach over standard management.24 But, It is difficult to draw firm conclusions for IBD because the trial did not have the statistical power to test hypotheses within each disease subgroup, and the ITL threshold (>3μg/mL) for allowing treatment optimisation seems very low based on recent data in IBD.14

NOR-DRUM B investigated the effects of the proactive TDM approach in patients receiving maintenance IFX. The primary outcome was loss of response over the course of 52 weeks in patients who had already been on IFX for at least 30 weeks.25 Standard care was associated with a higher risk of disease worsening than the TDM arm over the 52-week trial and more frequent formation of ATIs at concentrations considered to be clinically significant. Finally, a randomised controlled trial of paediatric patients with CD by Assa et al.,26 showing that proactive monitoring of adalimumab achieves greater clinical remission without corticosteroids than reactive monitoring.

In addition to the possible limitations of the studies mentioned above, we emphasise that most of the studies performed on TDM-based decisions to adjust doses of infliximab in IBD patients base their dose adjustment strategies on the use of algorithms.13,17 We consider this practice to have certain limitations (it does not take into consideration inter-individual variability, it requires drug concentrations to be kept in a steady state in some cases and the parameters that affect the pharmacokinetics of IFX are not taken into account).

The Bayesian approach allows for dose optimisation to ensure therapeutic concentrations of IFX are maintained and thus optimise the efficacy of IFX. The individual PK parameters can be estimated (empiric Bayes estimates) based on patient characteristics and drug concentration measurements and subsequently be used to predict the next dose that is required for that patient to achieve a predefined exposure target.27 In our study, we consider that the proportion of patients who achieved ITL in the therapeutic range was moderate (75% at week 52). This may be explained by the small number of determinations per patient and the short follow-up period in our study. The PRECISION trial 21 demonstrated that the use of a Bayesian dashboard for IFX dosing in maintenance treatment for IBD patients resulted in a significantly higher proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission during one year of follow-up compared to standard dosing. Another study carried out by our group showed that TDM assisted by a Bayesian dose adjustment led to a higher proportion of patients achieving an optimal ITL than the adjustment by algorithms.19

Moreover, the PK software used in our study was designed for research applications rather than for clinical use. Its use in daily clinical practice is labour-intensive and beyond the capabilities of most clinical practices.15 More user-friendly PK software programmes are needed for use in the clinical context, which will have the potential for a better integration with electronic medical records.28

In our study, the immunogenicity of infliximab was only detected in 9/75 (12%) patients in the TDM-group. This can be explained because drug-sensitivity assays were used to detect the presence of ATIs. A disadvantage of this type of assay is that anti-drug antibodies only be detectable in the absence of drug, which could underestimate the rate of immunogenicity. However, it seem that the presence of ADA when the drug is still detectable by a drug-tolerance assay may not be clinically relevant.14

Our study had several limitations. First, it was retrospective, with a study period between 2007 and 2020. The management of anti-TNF drugs changed over that time, and this could have influenced the results of the study. Despite the retrospective nature of the study, however, the data collected for the TDM were obtained prospectively, which reduced the amount of missing data. Second, due to the small sample size, it was not possible to obtain significance in some outcomes and subgroup analysis. Third, the lack of information regarding inflammatory markers (CRP and FCP) and data endoscopic in many patients did not allow for an adequate evaluation of the impact of TDM on the biochemical and endoscopic response.

Despite these limitations, our results are relevant because they provide evidence on the usefulness of proactive TDM supported by the Bayesian approach. After the regression analysis, the main variable associated with clinical remission and better clinical outcomes was dose optimisation using the Bayesian approach. Dose escalation was found to be associated with poor clinical control. This can be explained by the fact that the proportion of patients with poor clinical control who received an intensified IFX regimen was higher in the ST than in the TDM-group. Wu et al. have shown that TDM helped to identify unnecessary use of IFX in 30.6% of the TDM tests performed in luminal Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients. Marquez et al. 29 did a systematic review to identify the scientific evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of the use of TDM for anti-TNF in IBD, mostly based on IFX, and showed that IFX TDM is cost-effective in the management of IBD.

In conclusion, the results obtained in our study support the proactive TDM of IFX in the maintenance phase, with statistically significant differences between both groups, thus demonstrating better disease control and fewer complications in patients with proactive TDM. Future prospective studies are needed to examine the usefulness of proactive TDM in the maintenance phase and consider the Bayesian approach as a dose individualisation strategy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.