There are no studies on efficacy of tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis (UC) in Latin America. The aim of this study was to describe the efficacy and safety, in the real world, of patients with moderate-severe UC treated with tofacitinib in our setting.

Materials and methodsMulticenter descriptive observational study, in patients with UC who received treatment with tofacitinib in induction phase for 8 weeks and then, maintenance therapy, between June 2019 and June 2022.

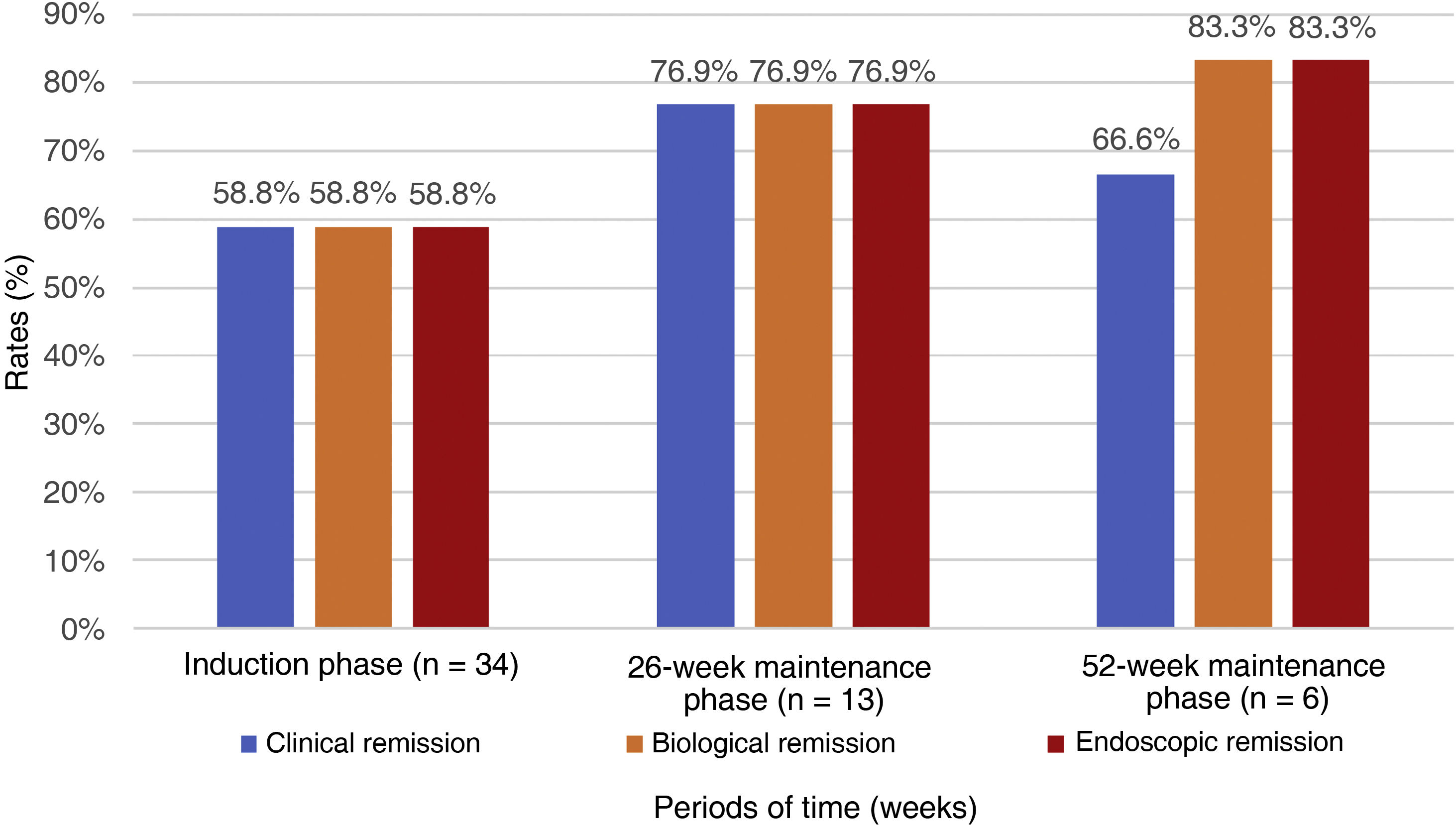

ResultsThirty-four adult patients, 50% female, mean age 38.1 (range 22–72) years. 76.5% pancolitis, and 20.6% left colitis. 79.4% failure to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (anti-TNFs), and 35.3% to vedolizumab. 14.7% naïve to biologic therapy. 23.5% had previous extraintestinal manifestations. During induction, 58.8% of patients achieved clinical, biochemical and endoscopic remission. During maintenance, 76.9% of patients at 26 weeks and 66.6% at 52 weeks presented clinical remission. Eight patients presented adverse events, none of them cardiovascular or thromboembolic. 44.1% were steroid-dependent, and 23.5% required steroids as rescue therapy. 38.3% required an increase in tofacitinib to 10 mg every 12h during maintenance. In 17.6% tofacitinib was discontinued due to lack of efficacy. We included three pediatric-aged female patients, mean age 15.3 (range 14–17) years, 2/3 with pancolitis and 1/3 with left colitis, all with prior exposure to biologic therapy, who had clinical, biologic and endoscopic remission at induction.

ConclusionsIn this first Latin American study with tofacitinib in UC, efficacy and safety are demonstrated in the treatment of our patients with moderate to severe activity.

No hay estudios sobre eficacia de tofacitinib para colitis ulcerosa (CU) en Latinoamérica. Se plantea como objetivo describir la eficacia y seguridad, en mundo real, de pacientes con CU moderada-grave tratados con tofacitinib en nuestro medio.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo multicéntrico, en pacientes con CU que recibieron tratamiento con tofacitinib en fase de inducción por 8 semanas y luego, terapia de mantenimiento, entre junio de 2019 y junio de 2022.

ResultadosTreinta y cuatro pacientes adultos, 50% mujeres, edad media 38,1 (rango 22–72) años. El 76,5% presentó pancolitis y el 20,6% colitis izquierda; el 79,4% fallo a inhibidores del factor de necrosis tumoral (anti-TNF) y el 35,3% a vedolizumab; el 14,7% era naïve a terapia biológica; el 23,5% presentó previamente manifestaciones extraintestinales. Durante la inducción, el 58,8% de los pacientes alcanzaron remisión clínica, bioquímica y endoscópica. En el mantenimiento, el 76,9% de los pacientes a las 26 semanas, y el 66,6% a las 52 semanas, presentaron remisión clínica; 8 pacientes presentaron eventos adversos, ninguno cardiovascular ni tromboembólico. El 44,1% fueron dependientes de esteroides, y el 23,5% requirieron esteroides como terapia de rescate. El 38,3% requirió aumento de tofacitinib a 10 mg cada 12 h durante el mantenimiento. En el 17,6% se suspendió tofacitinib por ausencia de eficacia. Se incluyeron 3 pacientes en edad pediátrica, femeninas, edad media 15,3 (rango 14–17) años, 2/3 con pancolitis y 1/3 con colitis izquierda, todas con exposición previa a terapia biológica, quienes presentaron remisión clínica, biológica y endoscópica en la inducción.

ConclusionesEn este primer estudio latinoamericano con tofacitinib en CU se demuestra eficacia y seguridad en el tratamiento de nuestros pacientes con actividad moderada a grave.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a multifactorial chronic disease whose pathogenesis is still poorly understood.1 Despite the therapeutic arsenal available, treatment failure is still common and there are many unmet needs in the treatment of patients with UC.2

Within the wide range of available treatments, JAK inhibitors represent one of the most innovative in immune and inflammatory diseases. Tofacitinib selectively inhibits signal transduction activated by heterodimeric cytokine receptors, which bind to JAK3 and/or JAK1, with superior functional selectivity to that of cytokine receptors, which activate signal transduction via JAK2 pairs. It has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of adults with moderate/severe UC with inadequate response or intolerance to anti-TNF.3 In the OCTAVE pivotal phase 3 clinical trial programme, dose-dependent efficacy was demonstrated for the induction and maintenance of clinical remission in moderate to severe active UC. For induction (eight weeks), in OCTAVE I with 10mg, clinical remission was found in 18.5% and endoscopic improvement in 31.3%; OCTAVE 2 reported clinical remission in 16.6% and endoscopic improvement in 28.4%; while for maintenance (52 weeks), OCTAVE Sustain demonstrated clinical and endoscopic remission in 34.3% and 37.4% with 5mg and in 40.6% and 45.7% with 10mg, respectively.4 It has an acceptable safety profile, and there is increasing information on its use in clinical practice.5–8

In Latin America, population studies have shown an increase in the incidence and prevalence of UC.9 Colombia is classified as a country with an intermediate prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and specifically in UC, the incidence and prevalence having increased from 5.59/100,000 and 37.63/100,000 in 2010, to 6.3/100,000 and 58.14/100,000 in 2017, respectively.10 Tofacitinib has been approved in Colombia by the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos (INVIMA) [National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance] since 2019 as an induction and maintenance therapy in adults with moderate/severe UC with inadequate response, loss of response or intolerance to corticosteroids, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or anti-TNF (INVIMA 2019M-0014423-R1).11 Information about the use of tofacitinib for moderate/severe UC in the real world remains limited. There is information available from different regions of the world. In the English-speaking literature there is the TOUR study,12 in which steroid-free remission was found at weeks 2, 4 and 8 in 25%, 30.2% and 29.2% of patients, respectively. Meanwhile, in the European literature, there is the experience of the ENEIDA registry,7 in which clinical remission of 31% and 32% at weeks 8 and 16, respectively, was documented. However, there are no data specifically for Latin America. The main aim of this study was therefore to describe the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in the management of patients with moderate/severe UC, both those having had biological therapy and naïve patients, as well as initial experience in the paediatric population.

Material and methodsStudy design and data miningWe conducted a descriptive, retrospective, multicentre observational study; using convenience sampling, we included both adult and paediatric patients with moderate/severe UC, seen either in outpatient clinics or in hospital from June 2019 to June 2022 in 10 Gastroenterology and Colorectal IBD referral centres in different cities in Colombia.

UC activity was defined by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index.13 Patients 18 years of age or older were considered adults, and the paediatric population was defined as two to 17 years of age. Patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis were excluded. The decision to use tofacitinib was based on clinical judgement and discussion with the patient.

Treatment regimenFor induction of remission, the regimen was oral tofacitinib 10mg twice daily for eight weeks. In selected cases with a partial response to the initial eight-week therapy, defined as a Mayo score ≥3 points or a reduction ≤3 points in the Mayo score or in the partial Mayo score,14 we considered extending the induction time to 16 weeks. For long-term maintenance, the regimen was tofacitinib 5mg twice daily.3,4,13,15 Patients who relapsed after tofacitinib dose reduction had their dose increased to 10mg every 12h.

Data collectionWe used the medical records as the primary source of information. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected prior to starting tofacitinib, including gender, age, distribution of UC (E1: proctitis, E2: left-sided, and E3: extensive or pancolitis) according to the Montreal classification,16 age at diagnosis of UC, age when starting tofacitinib, time from onset of UC to starting tofacitinib, measurement of extent according to the Montreal score,16 previous use of anti-TNF and/or anti-alpha4beta7 integrin, classification of the severity of UC according to the ACG, Mayo endoscopic score,17 as well as biochemical values (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], faecal calprotectin, haemoglobin [Hb]). Therapeutic response was assessed at different time points, which included completion of induction, and at 26 and 52 weeks during maintenance. Clinical parameters were measured (absence of abdominal pain, diarrhoea and rectal bleeding), in clinical and biochemical remission; as well as endoscopic remission, including the variables that make up the Mayo endoscopic score17 and UCEIS (Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity).18 The frequency of adverse events, use of steroids, presence of extraintestinal manifestations (EIM), surgical requirement for IBD, hospitalisations and changes in the tofacitinib treatment regimen were also measured.

DefinitionsEndoscopic remission was considered as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 119; biochemical remission as having normal CRP parameters (below 5mg/l), ESR (below 20mm/h) and calprotectin (below 150μg/g), without anaemia (defined in females: haemoglobin <11.9g/dl [119g/l] or haematocrit <35%; males: haemoglobin <13.6g/dl [136g/l] or haematocrit <40%)19; and clinical remission as Mayo total score ≤2, with no subscores >1 and rectal bleeding subscore of 0.14 Patients who had to discontinue tofacitinib due to adverse events before week eight were considered non-responders.14

Statistical analysisThe database was set up in Excel version 2019. Confidentiality of information was guaranteed and none of the records contained sensitive information on patient identity. The information obtained was reviewed by three different people. Information was processed in the social sciences program SPSS version 25.0. For the descriptive analysis of quantitative variables, the arithmetic mean, minimum, maximum and standard deviation were used, and for qualitative variables, absolute and relative frequencies. The design took into account the requirements laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki, version 2013, in Fortaleza, Brazil,20 and resolution 8430 of 1993, of the Colombian National Ministry of Health,21 such that, as it was considered risk-free research and the confidentiality and safekeeping of the information collected was guaranteed, no informed consent was required. The participants were told what the research consisted of during the application of the instrument. This research was reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of each participating institution.

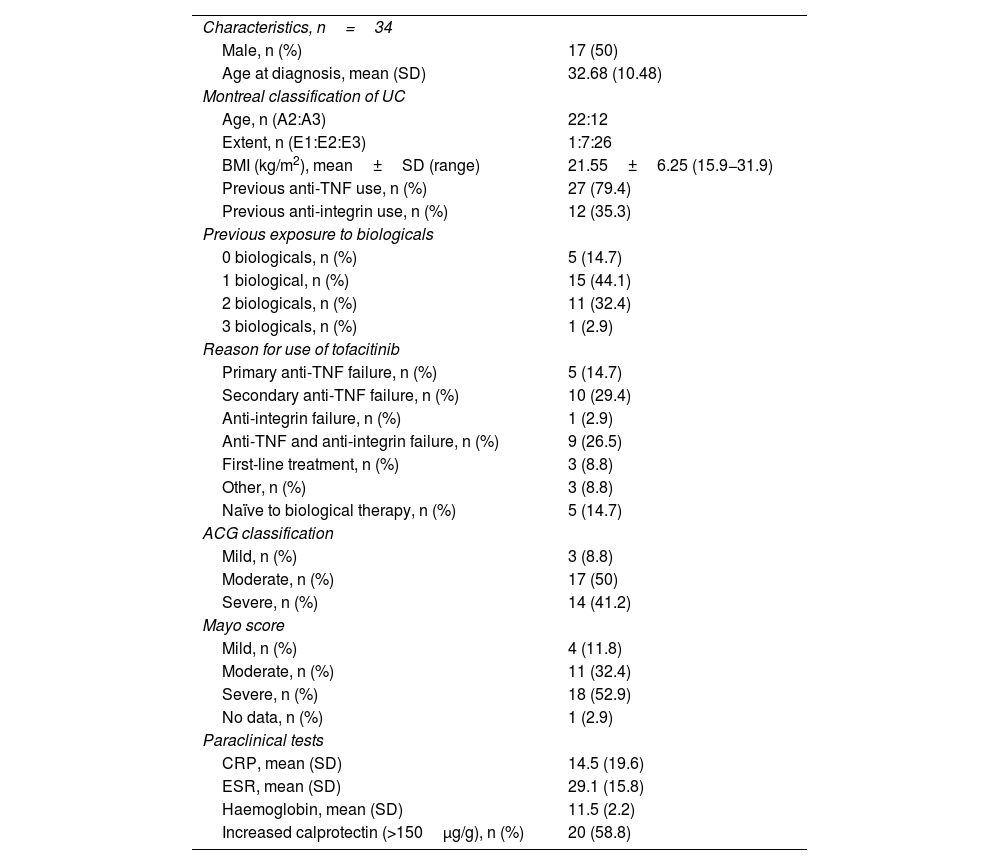

ResultsBaseline characteristicsThirty-four subjects met the selection criteria. Fifty percent were female, with a mean age of 38.1 years (SD 12.9) (range 22–72). All had moderate/severe UC, 76.5% of patients had pancolitis and 20.6% left-sided colitis. The mean time between diagnosis of UC and starting tofacitinib was 5.3 years (SD 4.9) (range 0–23.8). The clinical, biological and endoscopic baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Clinical description of patients with UC treated with tofacitinib.

| Characteristics, n=34 | |

| Male, n (%) | 17 (50) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 32.68 (10.48) |

| Montreal classification of UC | |

| Age, n (A2:A3) | 22:12 |

| Extent, n (E1:E2:E3) | 1:7:26 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD (range) | 21.55±6.25 (15.9−31.9) |

| Previous anti-TNF use, n (%) | 27 (79.4) |

| Previous anti-integrin use, n (%) | 12 (35.3) |

| Previous exposure to biologicals | |

| 0 biologicals, n (%) | 5 (14.7) |

| 1 biological, n (%) | 15 (44.1) |

| 2 biologicals, n (%) | 11 (32.4) |

| 3 biologicals, n (%) | 1 (2.9) |

| Reason for use of tofacitinib | |

| Primary anti-TNF failure, n (%) | 5 (14.7) |

| Secondary anti-TNF failure, n (%) | 10 (29.4) |

| Anti-integrin failure, n (%) | 1 (2.9) |

| Anti-TNF and anti-integrin failure, n (%) | 9 (26.5) |

| First-line treatment, n (%) | 3 (8.8) |

| Other, n (%) | 3 (8.8) |

| Naïve to biological therapy, n (%) | 5 (14.7) |

| ACG classification | |

| Mild, n (%) | 3 (8.8) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 17 (50) |

| Severe, n (%) | 14 (41.2) |

| Mayo score | |

| Mild, n (%) | 4 (11.8) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 11 (32.4) |

| Severe, n (%) | 18 (52.9) |

| No data, n (%) | 1 (2.9) |

| Paraclinical tests | |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 14.5 (19.6) |

| ESR, mean (SD) | 29.1 (15.8) |

| Haemoglobin, mean (SD) | 11.5 (2.2) |

| Increased calprotectin (>150μg/g), n (%) | 20 (58.8) |

ACG: American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; Anti-TNF: tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; n: number of patients; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis.

With regard to biological therapy, 27/34 patients (79.4%) had previously failed anti-TNF, and among these subjects, 40.7% had used two anti-TNF; only one patient had received three anti-TNF. The anti-TNF used was adalimumab in 17 cases (50%), infliximab in 18 (52.9%) and golimumab in one (2.9%). Additionally, 12 (35.3%) required use of anti-alpha4beta7 integrin (vedolizumab). Five patients (14.7%) were naïve to biological therapy; 8/34 patients (23.5%) had EIM before starting tofacitinib.

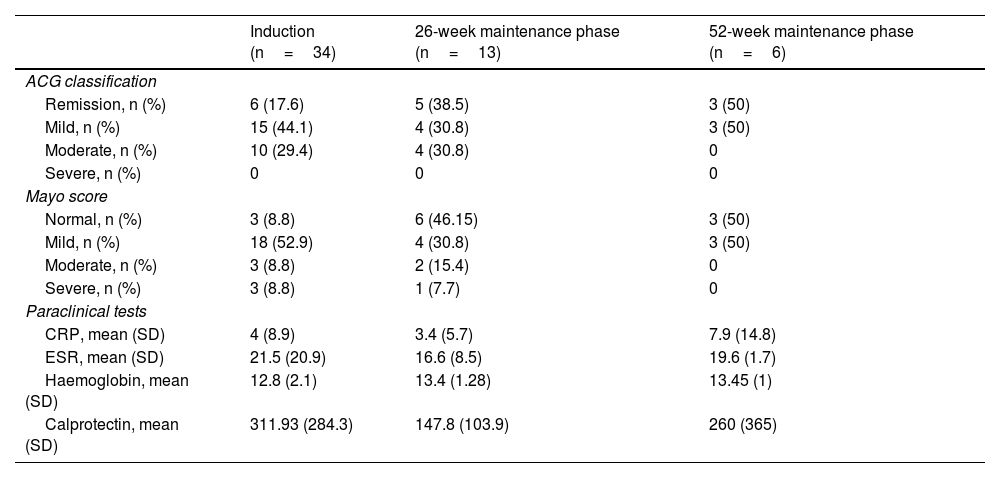

General efficacy, exposed to biological therapy and naïve to biological therapyAfter the induction phase, 58.8% of the patients achieved clinical and biological remission. According to the ACG score, 61.7% had only mild activity or were in remission. Endoscopically, 53% of the patients had a Mayo score of 1, and 8.8% a Mayo score of 0. The results in the induction phase are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1; 15/34 patients (44.1%) used corticosteroids during the induction phase, and of these, 53.3% were able to stop, 40% reduced the dose, and only one patient required an increase in dosage. No cases of non-responders were documented.

ACG classification, Mayo endoscopic score and paraclinical tests during the different treatment phases evaluated.

| Induction (n=34) | 26-week maintenance phase (n=13) | 52-week maintenance phase (n=6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACG classification | |||

| Remission, n (%) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (50) |

| Mild, n (%) | 15 (44.1) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (50) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 10 (29.4) | 4 (30.8) | 0 |

| Severe, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mayo score | |||

| Normal, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 6 (46.15) | 3 (50) |

| Mild, n (%) | 18 (52.9) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (50) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (15.4) | 0 |

| Severe, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| Paraclinical tests | |||

| CRP, mean (SD) | 4 (8.9) | 3.4 (5.7) | 7.9 (14.8) |

| ESR, mean (SD) | 21.5 (20.9) | 16.6 (8.5) | 19.6 (1.7) |

| Haemoglobin, mean (SD) | 12.8 (2.1) | 13.4 (1.28) | 13.45 (1) |

| Calprotectin, mean (SD) | 311.93 (284.3) | 147.8 (103.9) | 260 (365) |

ACG: American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; n: number of patients; SD: standard deviation.

During the 26-week maintenance phase, information was gathered on 13 patients, 76.9% reporting clinical, biological and endoscopic remission; with 30.8% achieving mild activity and 38.5% achieving remission according to the ACG score. Endoscopically, 4/13 (30.8%) had a Mayo score of 1 point, and 6/13 (46.2%) scored 0. The results in the maintenance phase at 26 weeks are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Information obtained from the maintenance phase at 52 weeks on six patients (Table 2 and Fig. 1) show 5/6 subjects (83.3%) were in biochemical and endoscopic remission, and 4/6 (66.7%) clinical remission. According to the ACG score, 3/6 (50%) achieved mild activity and 3/6 (50%) remission. Endoscopically, 3/6 (50%) had a Mayo score of 1 point, and 3/6 (50%) had a score of 0.

Eight patients (23.5%) required corticosteroids during the maintenance phases, of whom 2/8 (25%) were able to stop, 5/8 (62.5%) reduced the dose and 1/8 (12.5%) required an increase in dosage. In 6/34 cases (17.6%), tofacitinib had to be withdrawn due to lack of efficacy, 13/34 patients (38.3%) had to continue with 10mg every 12h during maintenance and 69.2% of them were unable to reduce the dose; 6/34 subjects (17.6%) were hospitalised for IBD during the treatment. One patient (2.9%) required surgery for UC, had already had failure to anti-TNF and anti-integrin, and required withdrawal of tofacitinib in the maintenance phase due to lack of response.

With regard to subjects previously exposed to biologicals (85.3% of the sample), in the induction phase, 55.6% achieved clinical and biological remission. According to the ACG score, 58.6% had only mild activity or were in remission. Endoscopically, 44.8% of patients had a Mayo score of 1 and 10.3% a Mayo score of 0. For the 26-week maintenance phase, information was collected on 10 patients, of whom 8/10 (80%) achieved clinical, biological and endoscopic remission. Endoscopically, 30% of the patients had a Mayo score of 1 and 50% a Mayo score of 0. According to the ACG marker, 40% achieved mild activity and 40% remission. Information obtained from the maintenance phase at 52 weeks on five patients shows 4/5 (80%) were in biochemical, clinical and endoscopic remission. According to the ACG score, 3/5 (60%) achieved mild activity and 2/5 (40%) remission. Endoscopically, 2/5 (40%) had a Mayo score of 0 points and 2/5 (40%) had a score of 1. Overall, 51.7% of patients previously exposed to biologicals required corticosteroids during the induction phase. These were discontinued in 6/15 (40%), the dose was reduced in 4/15 (26.7%), while 1/15 (6.7%) required an increase in dosage. Corticosteroids were required for maintenance by 20.7% of patients previously exposed to biologicals; these were discontinued in 1/6 (16.7%), the dose was reduced in 4/6 (66.7%), while 1/6 (16.7%) required an increase in dosage.

All subjects naïve to biologicals (14.7% of the sample) achieved clinical and biological remission in the induction phase. According to the ACG score, 4/5 subjects had only mild activity or were in remission. Endoscopically, the five patients had a Mayo score of 1. For the 26-week maintenance phase, information was collected on two patients, both of whom achieved clinical, biological and endoscopic remission; according to the ACG marker, one subject had mild activity and the other was in remission. For the 52-week maintenance phase, information was only obtained from one patient, who was found to be in clinical, biological and endoscopic remission, and achieved remission according to the ACG marker. With regard to the patients naïve to biological therapy, 4/5 required corticosteroids during the induction phase; withdrawal was achieved in 2/4, and the dose was decreased in the other 2/4. Last of all, 2/5 patients naïve to biological therapy required corticosteroids during maintenance; withdrawal was achieved in one and the dose was reduced in the other.

Safety profileOf the 34 patients, eight (23.5%) developed adverse events (1 severe headache, 1 alopecia areata, 1 herpes zoster, 3 non-severe infections other than herpes zoster, and 2 patients had non-significant lipid profile abnormalities). None of the patients required permanent withdrawal of tofacitinib due to adverse events. The cases of alopecia areata and herpes zoster, the cases of hyperlipidaemia and the three cases of non-severe infections occurred in patients with previous exposure to biological therapy. The severe headache was suffered by a biological therapy-naïve patient. The abnormal lipid profiles were reported in the induction phase in both patients, neither of which requiring lipid-lowering therapy. The only case of herpes zoster infection occurred in week six of treatment, with involvement of only one dermatome. Therapy was discontinued while valganciclovir was administered for 10 days, with no complications after therapy was resumed. In total, 4/34 patients (11.8%) were vaccinated against herpes zoster before the start of treatment, one case with recombinant vaccine and three with live attenuated virus vaccine, due to national availability. No thromboembolic or cardiovascular events or leucopenia were reported.

Patients with extraintestinal manifestationsBefore starting tofacitinib, 23.5% of the patients had a history of EIM; 4/8 (50%) of them had two or more EIM concomitantly and 1/8 (12.5%) had three. The most common were axial spondyloarthropathy (axSpA) in 3/8 (37.5%) and peripheral arthritis (PA), also in 3/8 subjects (37.5%), followed by primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), erythema nodosum (EN) and uveitis, each in 2/8 subjects (25%). In 6/8 (75%) of these subjects the EIM resolved with tofacitinib. The EIM resolved during induction in just two of these cases, one with axSpA and the other with uveitis, PA and EN at the same time. In terms of therapeutic goals, during induction, 5/8 (62.5%) achieved biochemical and endoscopic remission, and 6/8 (75%) clinical remission. Of the EIM subjects who failed to meet therapeutic goals during induction, 2/3 achieved biochemical, clinical and endoscopic remission and 2/2 patients achieved clinical remission in the 26-week maintenance phase.

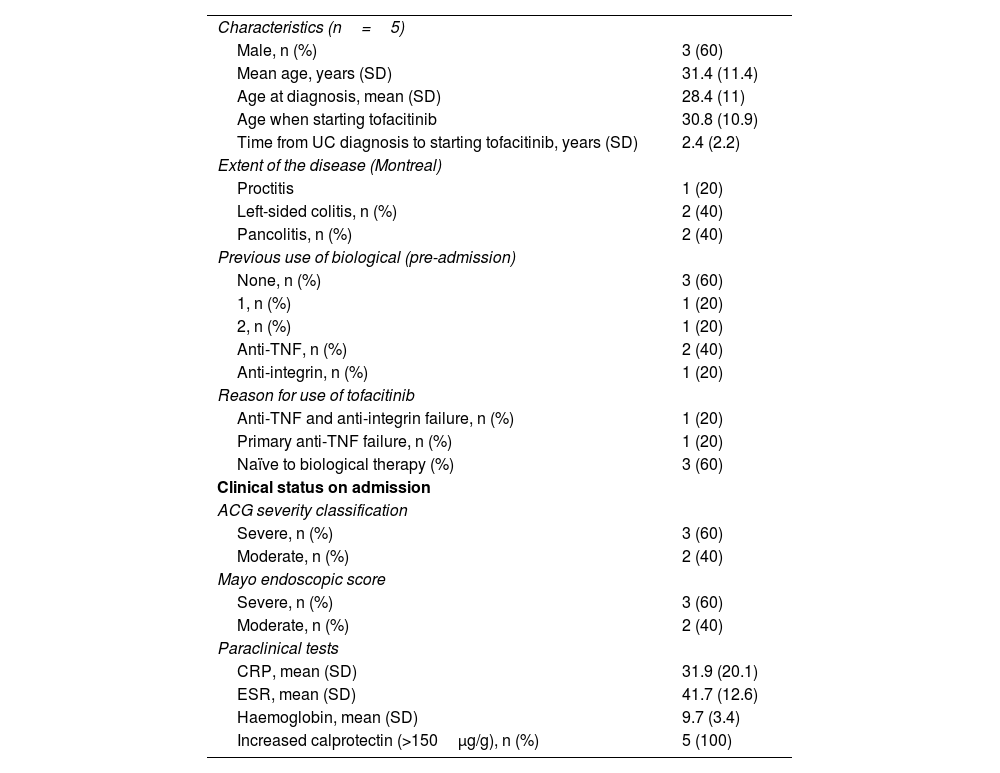

Patients hospitalised with moderate to severe ulcerative colitisFive patients, 3/5 male, mean age 31.4 years (range 15–42; SD 11.41), all with moderate to severe UC, 2/5 patients with pancolitis and 2/5 with left-sided colitis. The mean age at diagnosis was 28.4 years (SD 11) (range 14.3–39.8), the mean time between disease onset and tofacitinib was 2.4 years (SD 2.3) (range 1.8–6); 3/5 had not received biological treatment, 1/5 had experienced failure to anti-TNF and 1/5 failure to anti-TNF and anti-integrin. All the patients were hospitalised for disease activity and had severe symptoms as well as persistently increased inflammatory markers. During induction, all five patients achieved clinical and biological remission, and 3/5 had endoscopic remission. The median time to discharge after starting the drug was six days (SD 1.1). After induction, the biochemical parameters showed improvement, although not statistically significant, with a mean decrease in CRP of 27.9mg/l (SD 20.1), in ESR of 24.4mm/h (SD 14.6) and in calprotectin of 707μg/g (SD 323.8), and an increase in haemoglobin levels of 3.8g/dl (SD 3.5). All remained in clinical and biological remission at 26 weeks. No adverse effects were reported, such as venous thromboembolism, infections requiring hospitalisation, herpes zoster reactivation or major cardiovascular events. Four out of five required steroids during induction; withdrawal was achieved in two cases and dose reduction in two. No immunosuppressants were required. No cases of non-responders were documented. In addition, at 26 weeks, none of the cases required surgical management (Table 3).

Clinical description of patients with acute moderate/severe UC treated with tofacitinib.

| Characteristics (n=5) | |

| Male, n (%) | 3 (60) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 31.4 (11.4) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 28.4 (11) |

| Age when starting tofacitinib | 30.8 (10.9) |

| Time from UC diagnosis to starting tofacitinib, years (SD) | 2.4 (2.2) |

| Extent of the disease (Montreal) | |

| Proctitis | 1 (20) |

| Left-sided colitis, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Pancolitis, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Previous use of biological (pre-admission) | |

| None, n (%) | 3 (60) |

| 1, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| 2, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| Anti-TNF, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Anti-integrin, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| Reason for use of tofacitinib | |

| Anti-TNF and anti-integrin failure, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| Primary anti-TNF failure, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| Naïve to biological therapy (%) | 3 (60) |

| Clinical status on admission | |

| ACG severity classification | |

| Severe, n (%) | 3 (60) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Mayo endoscopic score | |

| Severe, n (%) | 3 (60) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Paraclinical tests | |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 31.9 (20.1) |

| ESR, mean (SD) | 41.7 (12.6) |

| Haemoglobin, mean (SD) | 9.7 (3.4) |

| Increased calprotectin (>150μg/g), n (%) | 5 (100) |

ACG: American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; n: number of patients; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis.

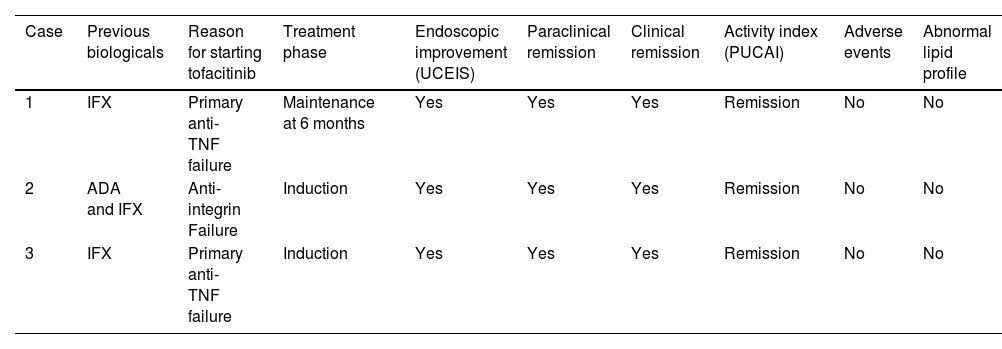

Three female patients, mean age 15.3 years (range 14–17; SD 1.5), PUCAI (Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index) classification severe in two patients and moderate in one. According to UCEIS characteristics, 2/3 had pancolitis and 1/3 left-sided colitis. Mean age at diagnosis was 14.33 years (SD 0.85) (range 13.5–15.2), while mean time between disease onset and starting tofacitinib was 1.25 years (SD 0.41) (range 0.8–1.6). All three patients had prior exposure to biological therapy, 2/3 with primary failure to anti-TNF and one case of failure to anti-TNF and anti-integrin. All three patients achieved clinical, biological and endoscopic remission during induction. Maintenance information was collected at 26 weeks in one female patient, who remained in remission. No cases of non-responders were documented. Characteristics and results are summarised in Table 4. No extraintestinal manifestations were documented. There were no drug-related adverse reactions, no infections and no cardiovascular or thrombotic events. In one case, immunosuppression with azathioprine was required; no steroids were used during the induction. There was no need for surgical management and no UC-related hospital admissions. All three patients even continued with their school activities without any obstacles throughout their drug treatment; no anxiety or rejection reactions were documented when taking the drug.

Clinical characteristics of paediatric patients with moderate/severe UC treated with tofacitinib.

| Case | Previous biologicals | Reason for starting tofacitinib | Treatment phase | Endoscopic improvement (UCEIS) | Paraclinical remission | Clinical remission | Activity index (PUCAI) | Adverse events | Abnormal lipid profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IFX | Primary anti-TNF failure | Maintenance at 6 months | Yes | Yes | Yes | Remission | No | No |

| 2 | ADA and IFX | Anti-integrin Failure | Induction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Remission | No | No |

| 3 | IFX | Primary anti-TNF failure | Induction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Remission | No | No |

ADA: adalimumab; IFX: infliximab; PUCAI: Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; UC: ulcerative colitis; UCEIS: Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity.

This study found that tofacitinib is effective and safe in patients with moderate to severe UC either previously exposed or naïve to biologicals, and in hospitalised patients with moderate or severe UC. It also showed efficacy in the control of EIM. The study included paediatric patients, demonstrating that tofacitinib is also effective and safe in this population.

The study findings deserve to be analysed in the light of the current therapeutic goals in UC; they include meeting therapeutic targets with clinical, biological and endoscopic remission, making tofacitinib a worthwhile alternative to consider in our population.

Despite our limited number of patients, being small compared to other cohorts, these data corroborate an adequate response in induction, and earlier steroid-free clinical remission compared to other cohorts.22,23 Our findings are similar to the results obtained in a British multicentre retrospective observational cohort, with 134 patients, in which 74% had responded to tofacitinib at week 8, and 44% of subjects were in steroid-free clinical remission at week 26,22 and a French cohort study with 38 patients, which reported clinical response in 45% at week 14, and steroid-free remission in 34% at week 48,23 confirming short-term efficacy and safety and suggesting that, compared to the reports from other international cohorts, the patients included in this study are probably less refractory to immunosuppressive therapies.

Furthermore, a considerable proportion of patients in our study, 79.4% and 35.3%, respectively, had a previous history of treatment failure with anti-TNF and anti-integrins. The treatment of these patients is a challenge considering the limited therapeutic arsenal and the fact that efficacy rates decrease after failure with a first biological agent. In line with other cohorts,22–24 the history of therapeutic failure prior to biological therapy in the cases included in this study did not affect the treatment efficacy of tofacitinib, with adequate rates found in terms of fulfilling therapeutic goals.

The patients in this study were characterised by various factors making them high risk for colectomy, including aged under 40 years at diagnosis, moderate/severe UC activity according to the Mayo score, and the fact that 76.5% had pancolitis, as the extent of the disease is known to be associated with a significant increase in the risk of colectomy.25 On top of all that, over 80% were refractory to biological therapy (including anti-TNF and/or vedolizumab). Despite being a descriptive study, and that our objectives did not include assessing the requirement for colectomy after administration of tofacitinib, we found that only one case (2.9%) required surgical treatment; this being a subject who met the above-mentioned high-risk criteria for colectomy, with anti-TNF and anti-integrin failure, and who required withdrawal of tofacitinib in the 26-week maintenance phase due to lack of efficacy. Apart from this exception, the low percentage of those not responding to therapy or requiring colectomy confirms our findings as very encouraging in the search for quality of life in these patients.

It is also important to mention EIM, the presence of which has previously been reported to entail a worse prognosis and to predict a more severe, more difficult to manage disease.26 In general, the majority of EIM were resolved with tofacitinib, which further positions the use of this drug for this patient profile, especially when the EIM affect the joints. However, it is important to remember that these patients had greater steroid requirements, increased doses of tofacitinib, hospitalisations for IBD, and non-severe infections. In view of these results, we believe prospective studies are required to shed more light on the efficacy of tofacitinib in patients with moderate/severe UC and EIM, especially over longer periods of time.

As regards adverse events, clinical trials with tofacitinib for rheumatoid arthritis have shown that the most common are flu-like symptoms, nasopharyngitis and increased levels of total cholesterol and high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL, respectively). In terms of risk factors, being over 65 years of age, corticosteroid doses greater than 7.5mg, diabetes and tofacitinib doses of 10mg versus 5mg were independently associated with the risk of severe infection.27 In this descriptive study, non-severe infectious processes were the most common, with only one case of herpes zoster, followed by abnormal lipid profile (5.8% of cases). These findings are not unusual and lipid profile abnormalities have been reported to be inversely related to changes in serum CRP levels.28 However, the mechanism by which tofacitinib may affect the lipid profile, whether directly or only through inflammatory changes, is still not fully understood.29 None of the patients required lipid-lowering treatment and the finding of tofacitinib-induced dyslipidaemia was not associated with any cardiovascular events. No cases of venous thromboembolism (VTE) were detected. However, this remains an issue, as the majority of patients in this study, although treated with tofacitinib 10mg twice daily, were under 40 years of age with no associated cardiovascular risk factors or previous history of VTE, and this differs from previous studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in which events associated with some of these risk factors were documented.6,30

Most of the patients included in this study had characteristics consistent with a more severe disease course, such as EIM and frequent use of corticosteroids. In addition, 41.2% had received treatment with ≥2 biologicals prior to tofacitinib (including anti-TNF and/or anti-integrin), and only 14.7% were naïve to biological therapy. In the patients included in this study, both those naïve to biological therapy and those with the previous use of two or more biological drugs, we found an appropriate rate of fulfilment of therapeutic goals in induction and maintenance at 26 weeks and a low percentage of adverse events (one case corresponding to severe headache), with none developing infections or thrombotic or cardiovascular events, or requiring admission to hospital. The results of this study are consistent with those of Chiorean et al.,31 where adherence to tofacitinib was high, showing an adequate safety profile and efficacy, with reduced corticosteroid use, and irrespective of a patient’s previous exposure to biologicals.

In the paediatric population, the use of tofacitinib for moderate/severe UC is “off-label”, and experience of its use is known from case series and reports,32,33 which have shown complete steroid-free clinical, endoscopic and biochemical remission, with no adverse events, no requirement for colectomy and a low hospitalisation rate. Our study included experience with three paediatric patients, where, in addition to safety, we were able to confirm rapid clinical response with sustained efficacy and early normalisation of biomarkers. These findings provide encouraging evidence for the efficacy and safety of treatment in young individuals with moderate/severe UC. However, prospective studies with a larger number of subjects are required to better characterise the efficacy of tofacitinib in this population group. The experience in hospitalised patients with acute moderate to severe UC is also purely observational.34 Taking into account the rapid action profile of this drug, it may be an option to consider as potential rescue therapy in moderate to severe acute UC in patients with prior therapeutic failure to infliximab, or when infliximab or ciclosporin are not available.

As a possible limitation of this study, it must be acknowledged that this was a descriptive retrospective study. However, it was conducted at 10 IBD referral centres, which gives credence to the results. Another limitation is the sample size; previous studies have assessed study samples with a larger number of subjects.22–24 However, it is worth noting that the epidemiological behaviour of IBD, and particularly UC, is different from one country and continent to another, as well as the fact that tofacitinib has been used in other geographical areas in moderate/severe UC since before it was approved in Colombia. Other possible limitations include difficulties with the clinical and paraclinical follow-up of these patients. On the one hand, in some there were problems in performing follow-up paraclinical tests (ESR, CRP, calprotectin), possibly related to socioeconomic factors and factors involving health administrators at a local level. On the other hand, there may have been incomplete follow-up in some patients, in whom no information was obtained in the 26- and 52-week maintenance phases, while others were still waiting for outpatient follow-up at the time of data collection. However, documented efficacy rates are consistent with clinical improvement and normalisation of inflammatory biomarkers, and available endoscopic follow-up data support endoscopic healing in patients treated with tofacitinib.

ConclusionsThis is the first retrospective cohort study assessing the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in UC in Latin America, and our results are consistent with those reported in the literature. In our population, tofacitinib is an effective and safe alternative in the treatment of moderate/severe UC, being effective both in patients naïve to biological therapy and in those with previous use of anti-TNF and anti-integrin. It produced a high response rate with induction treatment that was sustained over time, and did not cause any thrombotic or cardiovascular events. In subjects with EIM, tofacitinib is safe and effective for both UC and EIM. Although its use in paediatric patients is not approved at present, we decided to use it out of necessity to rescue patients with severe colitis and avoid colectomy, achieving suitable responses with adequate safety. Prospective studies with a larger number of patients are required to characterise and confirm its real-life efficacy and safety in our population.

FundingThe authors have no funding to declare.

Author’s contributionVPI, FJB and CFS: study design, patient recruitment, data collection and drafting of the manuscript. JRM, PG, CC, CR, NR, OA, GTF, RGD and JRM: patient recruitment and data collection. JSFO: study design, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval of the version submitted.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.