Cholestatic liver diseases comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting both adult and pediatric population, characterized by alterations in bile formation, secretion, or flow, leading to the accumulation of bile acids and other toxic substances in the liver. In recent years, advances in new pharmacological therapies, the availability of next-generation genetic sequencing techniques, and the development of specific treatments for genetic cholestasis have transformed the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to these conditions. This document, jointly prepared by the “Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado” (AEEH) and the “Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica” (SEGHNP), presents a national evidence-based guideline for the diagnosis and management of hepatic cholestasis in Spain. It addresses recommendations for differential diagnosis, diagnostic algorithms, indications for genetic studies, treatment and follow-up criteria in diseases such as primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, genetic cholestasis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and vanishing bile duct syndrome. In addition, recommendations are included for the management of extrahepatic complications, indications for liver transplantation, and special considerations in pregnancy and childhood. The guideline emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, the use of non-invasive tools for risk stratification, and the incorporation of new targeted therapies, with the aim of improving the prognosis and quality of life of patients affected by cholestatic liver diseases.

Las enfermedades colestásicas hepáticas comprenden un grupo heterogéneo de trastornos que afectan tanto a adultos como a población pediátrica, caracterizados por alteraciones en la formación, secreción o flujo biliar, lo que conlleva a la acumulación de ácidos biliares y otras sustancias tóxicas en el hígado. En los últimos años, el avance en nuevas terapias farmacológicas, la disponibilidad de técnicas de secuenciación genética de nueva generación y el desarrollo de tratamientos específicos para colestasis genética han transformado el abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico de estas patologías. Este documento, elaborado conjuntamente por la Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado (AEEH) y la Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (SEGHNP), presenta una guía nacional basada en la evidencia para el diagnóstico y manejo de la colestasis hepática en España. Se abordan recomendaciones para el diagnóstico diferencial, algoritmos diagnósticos, indicaciones de estudio genético, criterios de tratamiento y seguimiento en patologías como la colangitis biliar primaria, colangitis esclerosante primaria, colestasis genética, colestasis intrahepática del embarazo y el síndrome de desaparición de conductos biliares. Además, se incluyen recomendaciones sobre el manejo de complicaciones extrahepáticas, indicaciones de trasplante hepático y consideraciones especiales en el embarazo y la infancia. La guía enfatiza la importancia de un enfoque multidisciplinar, la utilización de herramientas no invasivas para la estratificación del riesgo y la incorporación de nuevas terapias dirigidas, con el objetivo de mejorar el pronóstico y la calidad de vida de los pacientes afectados por enfermedades colestásicas hepáticas.

Cholestasis encompasses a spectrum of hepatic disorders characterized by impaired bile formation, secretion, or flow, resulting in the accumulation of bile acids (BA) and other toxic substances in the liver. These conditions can affect both pediatric and adult populations. While each condition presents distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, they often share clinical manifestations, such as pruritus, jaundice, and progressive liver damage that may culminate in cirrhosis or necessitate liver transplantation (LT) over time.

In recent years, several pivotal developments have underscored the necessity of standardizing the diagnosis and management of cholestatic diseases: (1) the approval and availability of new pharmacological treatments for primary biliary cholangitis (PBC),1,2 (2) relevant information for the management of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) has been published,3 (3) the advancement and widespread accessibility of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques, which have enhanced the diagnosis of genetic cholestatic diseases in both pediatric and adult populations,4 and (4) the availability of therapeutic agents for the management of genetic cholestasis.5,6

This document will focus on providing guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of PBC, PSC (adults and children), genetic cholestasis (adults and children), cholestasis of pregnancy, and vanishing bile duct syndrome in Spain.

MethodologyIn 2023, the Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado (AEEH) and the Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (SEGHNP) convened a panel of experts to develop national clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cholestatic liver diseases in Spain. The guideline development followed internationally recognized standard operating procedures.

The expert panel first identified key clinical questions for each topic, structured using the PICO format (P: patient or population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome). These questions underwent a Delphi process involving 30 pediatric and adult hepatologists. Sufficient consensus was achieved after two rounds of voting.

Following this, a systematic review of the literature was conducted using PubMed. Each panelist was responsible for drafting statements and recommendations within a specific section of the guidelines, which were then reviewed and discussed by the full group. The panel met virtually five times, and all recommendations were collectively debated and approved (Supplementary Table 1).

The level of evidence supporting each statement was graded according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine system, and the strength of each recommendation was classified as either ‘strong’ or ‘weak’.7 The final endorsement of all recommendations was obtained through a second Delphi round.

CholestasisHow can cholestasis be diagnosed in adults?Recommendations:

- •

In case of cholestasis, detailed history and physical examination is mandatory. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

The abdominal ultrasound should be the first test to perform in case of cholestasis. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

AMA and PBC-specific ANA should be screened in patients with unexplained cholestasis. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

MRCP should be performed if previous tests are negative. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

Liver biopsy should be considered in patients with chronic cholestasis who remain undiagnosed. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

Genetic testing is recommended when previous tests are negative. (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

In selected cases with clinical history indicating a potential genetic cause of cholestasis, genetic testing can be performed before the liver biopsy. (LoE 5, weak recommendation).

Cholestasis can be asymptomatic or manifest as fatigue, pruritus, right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort, and jaundice. Biochemical markers include increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels, followed by conjugated hyperbilirubinemia at more advanced stages. Cholestasis is considered chronic if it lasts for >6 months and can be classified as intrahepatic or extrahepatic. Chronic cholestatic liver diseases often have an asymptomatic course over months or years and can be identified by elevated serum ALP levels. However, ALP can also originate from the bone, intestine, and placenta, and isolated ALP elevation should prompt the investigation of extrahepatic causes of this abnormality, including bone disease, vitamin D deficiency, or pregnancy.8

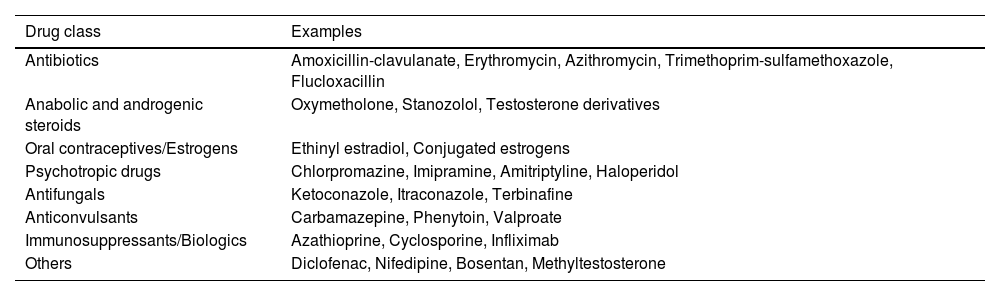

Elevation of ALP and GGT levels indicates a hepatic source, and patients need to undergo a structured diagnostic algorithm to establish the cause of this abnormality. A complete clinical history should include the presence of symptoms (pruritus, jaundice, abdominal pain), concomitant diseases (including thyroid disease, celiac disease, sicca syndrome, systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]), drug or herbal product consumption (Table 1), previous history of trauma or immunotherapy, family history of biliary problems or autoimmune diseases, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse. Physical examination should include the search for jaundice, xanthelasma, scratch lesions, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and other signs of chronic liver disease. Initial diagnostic testing should include abdominal ultrasound to rule out an extrahepatic cause of cholestasis and antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) and specific antinuclear antibodies (ANA) to confirm the diagnosis of PBC (see below). If negative, extended imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)3 can be performed to study the morphology of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary trees. In case of normality of the previous tests, literature recommends performing a liver biopsy to detect diseases involving the intrahepatic bile ducts (PBC, small-duct PSC), infiltrative or granulomatous liver diseases, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, peliosis, or signs of portosinusoidal vascular disease (PSVD) and hepatocellular cholestasis. Finally, recently published guidelines recommend performing a genetic test to discard the presence of genetic cholestasis when previously mentioned tests are negative.4 However, in cases of suspected genetic cholestasis, where liver biopsy information is limited, it is advisable to consider genetic testing prior to conducting a liver biopsy. This is particularly pertinent in selected cases where clinical indicators suggest potential genetic cholestasis, such as pruritus beginning in childhood or early adulthood, pruritus during pregnancy, the presence of biliary stones, a history of cholecystectomy, or a relevant family history (Fig. 1).

Drugs related to cholestatic drug-induced liver injury.

| Drug class | Examples |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Amoxicillin-clavulanate, Erythromycin, Azithromycin, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Flucloxacillin |

| Anabolic and androgenic steroids | Oxymetholone, Stanozolol, Testosterone derivatives |

| Oral contraceptives/Estrogens | Ethinyl estradiol, Conjugated estrogens |

| Psychotropic drugs | Chlorpromazine, Imipramine, Amitriptyline, Haloperidol |

| Antifungals | Ketoconazole, Itraconazole, Terbinafine |

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine, Phenytoin, Valproate |

| Immunosuppressants/Biologics | Azathioprine, Cyclosporine, Infliximab |

| Others | Diclofenac, Nifedipine, Bosentan, Methyltestosterone |

Evaluation of adult patients with cholestasis. Determination of BA may be considered in patients without conclusive findings in prior testing and with normal MRI/MRCP results. If BA are elevated, a genetic study may be considered without prior histological evaluation. ** A liver biopsy should be performed if not previously done (in cases where a genetic study was done without prior biopsy).

Recommendations:

- •

Prolonged neonatal jaundice, defined as jaundice beyond two weeks of age in both breast- and formula-fed infants, must be investigated, even in an otherwise “well-appearing” neonate. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

If cholestasis is present (defined as serum direct or conjugated bilirubin>1mg/dl if total bilirubin<5mg/dl or >20% of total bilirubin if it is ≥5mg/dl) the infant must be immediately referred to a specialized pediatric liver disease center. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

In the setting of cholestasis, treatment with nutritional support and fat-soluble vitamins should be initiated promptly. (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

Ultrasound must be performed as an initial assessment of cholestasis to exclude biliary obstruction. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

An elevated international normalized ratio (INR) without response to parenteral vitamin K administration should prompt ruling out causes of neonatal acute liver failure. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

Genetic tests should be performed early for the diagnosis of cholestatic infants. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

Jaundice is very common in the neonate, especially in breastfed infants, and it is usually secondary to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Cholestatic jaundice is an uncommon condition, occurring in approximately 1 in every 2500 term infants; however, it represents a potentially severe disease. It may go unnoticed because of its temporal overlap with the more common non-cholestatic neonatal jaundice. Cholestasis in infancy is defined as a serum conjugated bilirubin level of >1mg/dl, exceeding 20% of the total bilirubin concentration.

To ensure early detection of cholestasis, prolonged jaundice (defined as jaundice persisting beyond two weeks of age in a breastfed infant or at 2 weeks of age in a formula-fed infant) must be investigated, even in an otherwise well-appearing neonate.9–14 The initial step in the diagnostic approach should be obtaining a blood sample to measure total and conjugated bilirubin, GGT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and INR, along with urine culture.9–11,15 Stool color should also be assessed, as acholic or pale stools are considered a red flag.9–11 Direct visualization of the stool in the diaper by the physician is recommended as it is not uncommon for parents to fail to recognize acholic or hypocholic stools as abnormal.9–11 If cholestasis is identified, the infant must be referred immediately to a specialized pediatric liver disease center.9–11,14

The priority should be the detection of potential acute life-threatening conditions (e.g., sepsis, acute liver failure, urinary tract infection) or treatable diseases (e.g., inborn errors of metabolism such as galactosemia, hormone deficiency, inborn errors of primary bile acid synthesis) and early diagnosis of biliary atresia.12,14 It is also important to promptly start nutritional support12,15 and fat-soluble vitamin treatment to avoid the severe consequences of its deficiency.16

If prolonged prothrombin time or elevated INR are detected, parenteral vitamin K must be administered. If there is no response to this treatment, the causes of neonatal acute liver failure9 such as gestational alloimmune liver disease (GALD), inborn errors of metabolism, and infections, should be ruled out. GGT levels, whether elevated or within the normal range, provide an important initial clue for guiding stepwise evaluation of cholestatic infants. To further assess potential biliary obstruction, abdominal ultrasound is recommended as the first-line imaging modality in the initial workup for cholestasis.9,12

Advances in genetic testing and understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying bile formation and secretion have enhanced diagnostic capabilities, particularly in the setting of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). Consequently, genetic testing using next-generation sequencing (NGS) should be incorporated earlier in the diagnostic algorithm for infants with cholestasis.14,16–21 NGS has enabled a diagnosis in 22–61% of children with cholestasis,17,19–21 and this variability largely reflects differences in the study populations in which NGS was applied.9,11–13 Larger deletions, duplications, or inversions may not be detected by NGS, and in such cases, additional genetic studies such as whole exome sequencing (WES) or whole genome sequencing (WGS) may be required. It is important to note that variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be interpreted with caution and should not be used as the sole basis for establishing a molecular diagnosis.

Among the different causes of cholestasis in infancy, biliary atresia is the most common cause of pediatric end-stage liver disease and the leading indication for pediatric LT.10 Early diagnosis followed by timely surgical intervention with Kasai hepatic portoenterostomy is crucial and has been associated with improved transplant-free survival.

What is the differential diagnosis for neonatal or infant cholestasis with normal GGT levels?Recommendations:

- •

In infants with cholestasis and normal or low GGT levels, inborn errors in bile acid synthesis, panhypopituitarism, or PFIC should be investigated. (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

Normal GGT levels, elevated serum bile acid levels, and severe pruritus should prompt a diagnosis of PFIC. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

Recurrent hypoglycemia, cholestasis, micropenis, and septooptic dysplasia should increase the diagnosis of congenital hypopituitarism. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

In infants with cholestasis, normal or disproportionately low GGT values relative to the degree of cholestasis should prompt investigation to rule out specific conditions. These include inborn errors in primary bile acid synthesis,12,22 panhypopituitarism23,24 and PFIC with normal GGT levels.12,22 In fact, GGT-normal cholestasis beginning in the first months of life, accompanied by elevated serum BA and severe pruritus, should raise clinical suspicion of PFIC. PFIC encompasses a group of rare and heterogeneous autosomal recessive disorders caused by defects in the proteins involved in bile formation. Currently, the diagnosis of these conditions relies primarily on genetic analyses. Mutations in genes, such as ATP8B1, ABCB11, FXR, TJP2, MYO5B, USP53, UNC45, and VPS33B/VIPAS, are associated with cholestasis with normal GGT levels.15,22 In this context, the absence of pruritus and low serum bile acid levels may help differentiate inborn errors in primary bile acid synthesis25,26 from PFIC with normal GGT levels. Conversely, the combination of recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia and cholestasis should guide investigations to rule out congenital hypopituitarism.23,24 The presence of clinical features such as micropenis and septo-optic dysplasia further supports this diagnosis.

How should neonatal or infant cholestasis with elevated GGT level be studied?Recommendations:

- •

Biliary atresia should be ruled out in infants with cholestasis and elevated GGT levels. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

Loss of color or the presence of acholic stools should be assessed in infants with cholestasis and elevated GGT levels. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

Liver ultrasound should be performed as a first step in the evaluation of neonatal cholestasis with high GGT levels. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

There is no single diagnostic test for biliary atresia. Surgical exploration with intraoperative cholangiography is mandatory for disease confirmation. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

In the diagnostic evaluation of infants with high GGT cholestasis, ruling out biliary atresia must be a priority.10,12,13 Early diagnosis of biliary atresia and early Kasai hepatic portoenterostomy surgery are associated with better transplant-free survival.12,15 In this regard, liver ultrasonography must be performed as a first step to rule out biliary obstructive causes of cholestasis, such as sludge, stones, or choledochal malformations. It also allows for the identification of features suggestive of biliary atresia such as the “triangular cord sign” or an absent/abnormal gallbladder.9,10,12–15 Since no single diagnostic test can definitively confirm biliary atresia, surgical exploration with intraoperative cholangiography is essential to establish the diagnosis.10,12,13,15 A diagnosis of biliary atresia should be suspected in neonates or young infants who present with cholestasis with elevated GGT (>150–200IU/l) and acholic stools or progressive color discoloration. These findings should raise immediate concerns, as stool color is a critical early warning sign. Liver biopsy may be useful in the evaluation of infants with cholestasis10,12,13,15; however, its use should never delay exploratory surgery when there is a high clinical suspicion of biliary atresia. Typical histological findings of biliary atresia include ductal proliferation, bile plugs, and portal fibrosis.10,12,13,15 These changes may be absent in early biopsies (<1 month of age) and may be present in other causes of neonatal cholestasis.10,13–15 Therefore, the differential diagnosis should include biliary atresia, Alagille syndrome, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, MDR3 deficiency, Niemann–Pick type C, neonatal sclerosing cholangitis (e.g., Claudin-1 or DCDC2 deficiency), and other ciliopathies.

How should cholestasis with elevated GGT levels be studied at the onset of childhood or adolescence?Recommendations:

- •

A complete medical history, physical examination, and liver ultrasound should be performed for every patient with cholestasis and elevated GGT levels. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

Viral, autoimmune, metabolic, and genetic diseases should be included in the differential diagnoses. (LoE 5, strong recommendation).

- •

Liver biopsy may be considered in the absence of these findings. (LoE 5, weak recommendation).

A comprehensive medical assessment is crucial, beginning with a detailed medical history, including family history, travel history, exposure to toxins or medications, presence of concurrent autoimmune diseases, and presence of abdominal pain. It is critical to determine whether the presentation of symptoms suggests acute or chronic onset. Physical examination should be meticulously conducted to identify signs indicative of chronic liver disease, which will guide further diagnostic workup and prompt the consideration of extrahepatic manifestations, such as a cardiac murmur or distinctive facial features associated with Alagille syndrome.

As for neonates, abdominal ultrasound is an essential diagnostic tool for children or adolescents exhibiting high GGT cholestasis, serving to exclude biliary obstruction due to gallstones or biliary sludge, neoplastic growth, or choledochal cysts. Concurrently, the measurement of prothrombin time in cases of high GGT cholestasis is critical for early detection of acute liver failure.

Once biliary obstruction has been excluded, further work-up for liver disease should be guided by physical examination findings. This typically includes blood tests, such as viral serologies or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for pathogens, including Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis A, B, C, E, adenovirus, enterovirus, and herpes virus. Additional tests should include the measurement of alpha-1-antitrypsin levels and genotyping if levels are reduced, as well as autoimmunity markers, such as ANA, liver-kidney microsome type 1 (LKM-1) antibodies, and smooth muscle antibodies (SMA). The assessment of ceruloplasmin levels is also recommended.

In certain cases, liver biopsy and genetic sequencing may be indispensable to establish a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis should include conditions such as Alagille syndrome, PSC, secondary sclerosing cholangitis, MDR3 deficiency, and ciliopathies such as DCDC2 or KIF12 deficiencies.

Primary biliary cholangitisHow is PBC diagnosed?Recommendation:

The diagnosis of PBC should be established when two of the following three criteria are met: (a) biochemical evidence of cholestasis based on ALP elevation; (b) presence of AMA or other PBC-specific autoantibodies, including sp100 or gp210; and (c) histological evidence of nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis and destruction of interlobular bile ducts. (LoE 3, strong recommendation)

PBC must be considered in patients with persistent cholestasis, particularly when there is a sustained elevation of serum ALP levels. The cornerstone of PBC diagnosis is the detection of autoantibodies, particularly AMA, which target the E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. More than 90% of patients with PBC are positive for AMA. Immunofluorescence (at a titer of at least 1:40) and immunoenzymatically assays are highly specific for the disease in the presence of cholestasis. Additionally, ANA are detected in approximately 30% of patients with PBC. A thorough analysis of ANA is crucial, as certain ANA subtypes are highly specific for PBC (95%), but have relatively low sensitivity. In AMA-negative patients, the presence of ANA-immunofluorescence staining patterns, such as nuclear dots (indicative of anti-sp100 reactivity) or perinuclear rims (suggestive of anti-gp210 reactivity), is diagnostically valuable for confirming PBC.

In addition to ALP levels, other biochemical features are often observed in patients with PBC, although they are not exclusive to this condition. For example, elevated immunoglobulin levels, particularly IgM, are commonly observed. Additionally, these patients may present with elevated serum levels of AST and/or ALT, even in the absence of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), owing to the extent of liver inflammation and necrosis associated with PBC.

While liver biopsy is not essential for diagnosing PBC because of the high specificity of the autoantibodies in the presence of cholestasis, it has become a valuable diagnostic tool in cases where PBC-specific antibodies are absent or when there is a suspicion of concurrent AIH. Upon examination, the most common finding is chronic, non-suppurative inflammation that leads to the destruction of the interlobular and septal bile ducts, a condition referred to as ‘florid duct lesions’.

Is it necessary to determine the presence of anti-HK1 and anti-KLHL12 antibodies in patients with suspected PBC and other negative antibodies?Recommendation:

- •

Assessment of anti-HK1 and anti-KL12 antibodies is recommended in patients with suspected PBC when conventional autoantibodies are negative, (LoE 3, weak recommendation)

Among the various diagnostic challenges in PBC, identifying AMA-negative patients is one of the most significant, as it represents only approximately 5–10% of cases. In this situation, other autoantibodies can aid in the diagnostic process. In this context, specific ANA associated with PBC, such as sp100 or gp210, can be identified through indirect immunofluorescence in approximately 30% of cases that are negative for AMA.27 More recently, evidence suggests that anti-HK1 and anti-KLHL12 antibodies are present in approximately 40% of patients with PBC who are negative for AMA.28 Additionally, although further studies are needed, anti-HK1-positive individuals have been associated with significantly reduced transplant-free survival (TFS) and a shorter time to liver decompensation.29 Therefore, beyond their diagnostic ability, assessing these antibodies can add valuable prognostic information for patients suspected of having PBC, but who test negative for conventional antibodies.

What is the risk of developing PBC in patients with positive AMA (or specific ANA) without cholestasis?Recommendation:

- •

Although the risk is low, the 5-year incidence rate of PBC is 16% among patients with normal ALP levels and no evidence of advanced liver disease. (Statement, consensus 87%).

Although the presence of AMA (>1/40) is a strong indicator of PBC, AMA alone is not sufficient to establish a definitive diagnosis.30 In the general population, approximately 0.64% of people show AMA positivity,31 although most of these individuals will never develop PBC over time. A French prospective study showed that only one out of six patients (16%) with AMA positivity and normal ALP levels developed PBC within five years.32 More recently, a Chinese retrospective study suggested that this figure could be even lower, with a cumulative 5-year incidence rate of 4.2%.33 Therefore, it seems reasonable to conduct annual liver biochemistry monitoring in patients with positive AMAs and normal liver tests.

Is the determination of IgM levels useful in the diagnosis of PBC?Recommendations:

- •

Serum IgM levels can be measured as a complementary diagnostic parameter in patients with suspected PBC, especially in those who are antibody-negative or have normal serum ALP despite PBC-specific antibody positivity. (LoE 4, weak recommendation).

Elevated IgM levels are commonly observed during the diagnostic workup for PBC.34 While an increase in serum IgM concentration is indicative of polyclonal activity, it is not consistently observed as it is absent in approximately one-third of cases. Consequently, it cannot be regarded as a specific marker for PBC.35 Elevated IgM concentrations can be found in PBC as well as in acute viral infections, lymphomas, and protozoal parasitic infections.36 Thus, although high IgM concentrations are not considered a standard criterion for PBC,35,37 they can support diagnostic suspicion of PBC, particularly in patients with atypical presentations, such as those who are AMA-negative.35,38 It is important to highlight that the diagnostic performance of autoantibodies in PBC varies significantly across populations. One study revealed that a large proportion of Latin American/Hispanic patients with PBC may be AMA-negative. In these cases, IgM positivity has been identified as a potential diagnostic tool for AMA-negative PBC.39 Serum IgM levels may also be an important clinical indicator of PBC in patients with seropositive AMA but normal ALP levels. Ding D et al. performed a retrospective cohort study that included 115 AMA positive patients and normal ALP who were treatment-naïve and who underwent liver biopsy to establish a definitive diagnosis.40 The study showed that baseline serum IgM (>0.733×ULN) and age (>42years) are potential indicators for the diagnosis of PBC.41 Sun et al. studied 169 patients with positive AMA and normal ALP levels and found that serum IgM levels were elevated in 53.3% of cases. Liver biopsies were performed on 67 patients, revealing that 55 (82.1%) exhibited varying degrees of cholangitis activity, consistent with a PBC diagnosis.42

Is it necessary to perform liver biopsy in patients with suspected PBC and negative antibodies?Recommendations:

- •

Liver biopsy is recommended to establish the diagnosis of PBC in cases where specific autoantibodies are negative, particularly in AMA-negative patients, lacking access to PBC-specific ANA antibodies, or when biochemical characteristics of chronic cholestasis are present and PBC is suspected. (LoE 2, strong recommendation).

- •

Histological findings should be interpreted with caution, as characteristic histological lesions may be absent in the early stages of PBC. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

Liver biopsy is not routinely recommended in patients who meet the noninvasive criteria for PBC diagnosis but should be performed if biochemical and/or serological data are equivocal.37,38,43 Terziroli et al. studied a Swiss PBC cohort that included 30 patients with normal ALP level and positive AMA and/or PBC-specific ANA. Twenty-four (80%) had histological features of PBC, including three AMA-negative and PBC-specific ANA-positive patients. However, most of these patients had elevated GGT and the results should be interpreted with caution. The decision to perform a biopsy in these cases should be individualized based on the clinical context, additional diagnostic indicators, and thorough discussion of risks and benefits to the patient.44

Liver biopsy must be offered as a diagnostic measure in the absence of PBC-specific autoantibodies, unusual biochemical presentation (isolated increase in GGT), suspicion of a PBC/AIH variant, or any suspected hepatic comorbidity (including metabolic associated steatotic liver disease [MASLD] or alcohol-related liver disease).35,37,38,43

Histological examinations for the diagnosis of PBC, as with all liver biopsy interpretations, depend on the size of the liver tissue and the number of analyzable portal tracts.45 Histological alterations in PBC are heterogeneously distributed throughout the liver; therefore, the probability of identifying the presence of cholangitis and bile duct destruction increases with the number of portal tracts present. Thus, a biopsy of adequate quality should include at least 11 portal tracts.35,37,38,43,45 Cytokeratin 7 immunostaining, which highlights the loss of bile ducts, is recommended for bile duct identification.35,38 Hallmarks of PBC include destructive granulomatous lymphocyte cholangitis affecting the interlobular and septal bile ducts, leading to progressive bile duct loss, chronic cholestasis, fibrosis and cirrhosis.38 Other features that may be identified include interface hepatitis, parenchymal necroinflammation, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia.38 Characteristic features may be absent in the early stages of the disease (false-negative biopsies are likely in the very early stages).35,38 The typical diagnostic PBC florid duct lesion with segmental degeneration of the bile ducts and formation of poorly defined non-caseating epithelioid granulomas is found in only a small number of cases.46 However, in autoantibody-negative PBC, the differential diagnosis should include small-duct PSC, sarcoidosis, and other granulomatous diseases such as idiopathic ductopenia, drug-induced liver injury, graft-versus-host disease, and genetic cholestasis.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for staging liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. However, owing to its invasiveness and potential sampling errors, it is not routinely recommended for staging purposes at diagnosis,37,38,43,47 as the stage of PBC can be accurately assessed noninvasively. Histological liver examination for the initial evaluation of disease severity is only recommended in cases of failure, uncertainty or inconsistencies in liver stiffness measurement (LSM) results.35

How is the assessment of the risk of progression performed in patients with PBC?Recommendations:

- •

The stratification of future risk of progression should be based primarily on noninvasive tools, including demographics, clinical manifestations, biochemical and serological profiles, serum markers of fibrosis, and LSM. It can also be based on the results of invasive methods such as histological characteristics, endoscopic examinations, and direct measurements of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). (LoE2, strong recommendation).

The clinical course of PBC varies; some patients have slowly progressive disease, while others develop advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis within years and risk liver-related complications and death.43 This risk should be evaluated in all patients. The purpose of evaluating progression risk in PBC patients is: (1) identifying patients at highest risk of adverse outcomes to adapt treatment and monitoring; (2) evaluating therapeutic response to UDCA treatment to determine need for second-line treatment; and (3) detecting early complications, particularly cirrhosis, portal hypertension (PH), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).35 The stratification of future progression risk must be based primarily on noninvasive tools, including demographics, clinical manifestations, biochemical and serological profiles, serum markers of fibrosis, and LSM.9,11,12,18,35,37,38,43 It can also be based on results of invasive methods, such as histological features, endoscopic examinations, and direct measurement of the HVPG.35,38,43

Demographic factors have limited validation as prognostic tools for risk stratification in PBC. Age and sex influence treatment response and long-term outcomes of PBC patients.43 Patients presenting younger (<45 years) are often symptomatic and predisposed to severe progressive disease (rapid ductopenic form in young women) and poorer UDCA response.43 Male sex is associated with later diagnosis, more advanced disease at presentation, poorer UDCA response, and higher HCC risk.35,43 Whether sex serves as an independent prognostic factor for PBC outcome remains questionable. Cheung et al. performed a longitudinal retrospective study of 4355 patients in the Global PBC Study Cohort, including 17 centers across Europe and North America. They evaluated sex and age effects on UDCA treatment response and TFS in PBC patients. Younger patients (≤45 years) had higher serum transaminases than older patients and increased risk of treatment failure, LT, and death. However, in multivariate analysis, sex was not independently associated with response or TFS.48 Nevertheless, Abdulkarim et al. hypothesized that PBC diagnosis in male patients is delayed and prognosis impaired. They performed a case-control study comparing clinical features of 49 male patients and 98 age-matched female patients with PBC. Male patients reported fewer symptoms and were diagnosed at more advanced stages. HCC was exclusively observed in three male patients, with no cases among female patients. They suggested that men had a higher risk of HCC.49

In terms of clinical manifestations, fatigue or pruritus affects more than 50% of patients with PBC during the disease.35 Advanced disease is more likely to be associated with symptoms, and an impaired quality of life which may predict a worse response to UDCA and prognosis, but the evidence is controversial and limited.35,43 Nevertheless, a premature ductopenic variant characterized by severe pruritus, progressive icteric cholestasis, and a limited response to UDCA has been identified. In these patients, histological examination revealed bile duct loss without significant fibrosis, often necessitating LT.43

The biochemical measurements necessary for the initial assessment of disease severity should include a minimum of the following parameters: total and conjugated bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, and ALP and transaminase levels.35 Serum bilirubin has been recognized as the main predictor of poor outcome in PBC.43,50 Baseline bilirubin and albumin values have robust validation and applicability for stratifying risk in PBC.37,38,43 In fact, baseline bilirubin and albumin can stratify UDCA-treated patients into low- (normal bilirubin and albumin), medium- (abnormal bilirubin or albumin), and high-risk (both abnormal bilirubin and albumin) groups. Nevertheless, as both bilirubin and albumin levels are altered only in the advanced stages of the disease, they are not effective markers for risk stratification in patients at early stages of the disease.43 Very high ALP levels at diagnosis are usually indicative of severe and symptomatic disease with a lower likelihood of response to treatment.50 In fact, a study by Carbone et al. with data from the UK-PBC cohort found that elevated ALP and bilirubin at diagnosis, as well as low transaminase levels, younger age, longer time from diagnosis to first line treatment initiation, and worsening ALP from diagnosis were significantly associated with poor treatment response. Interestingly these variables serve to create the UDCA response score (URS) that can be used at diagnosis to define higher-risk patient.51 Gatselis et al. on behalf of the Global PBC Study Group,52 studied the factors associated with progression and outcomes of early stage PBC. From a cohort of 1615 patients with early stage PBC (based on normal levels of albumin and bilirubin) collected data from healthcare evaluations on progression to moderate PBC or advanced-stage PBC. The median follow-up time was 7.9 years, during which 904 patients progressed to a moderate stage, 201 developed advanced disease, and 236 experienced a clinical event. Variables associated with the transition from early to moderate stage included baseline levels of bilirubin, albumin, ALP, transaminase levels, platelet count, and UDCA treatment.52

Regarding serological markers, AMA titers at diagnosis do not correlate with disease stage, severity, or prognosis.43 In contrast, PBC-specific ANA are more frequently detected in patients with high risk PBC, and their presence may be predictive of an unfavorable course.35,37,38,43 Anti-centromere antibodies have also been reported to have a potential prognostic impact, as they are associated with a higher risk of PT.43 Nevertheless, their utility in risk stratification for PBC remains limited due to insufficient validation. Haldar et al. retrospectively analyzed data from 499 patients with PBC at a UK Liver Center for evaluating their diagnostic utility and prognostic significance in terms of TFS. Anti-gp210 autoantibodies were significatively associated with elevated serum transaminases, bilirubin and liver stiffness at presentation, non-response to UDCA and reduced TFS.53 In another retrospective study, Takano et al. showed that IgM levels were associated with cirrhosis-related symptoms and liver-related events, with significantly lower cumulative survival rates in patients with IgM levels ≥240mg/dl.54

When evaluating fibrosis using non-invasive approaches, the AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) has been validated in different cohorts as a predictor of adverse events, independent and additive to UDCA response. In a study conducted by Trivedi et al.,55 an APRI of >0.54 at baseline was found to predict the probability of LT or death. Moreover, an elevated APRI at baseline and/or during treatment was associated with an increased risk of adverse events during follow-up, independently of the biochemical response to UDCA.55 LSM, assessed using vibration-controlled transient elastography (TE), is a valuable tool for evaluating prognosis. Among the various alternative liver elastography techniques currently available, TE remains one of the most widely used and recognized worldwide. In an international multicenter retrospective follow-up study of 3985 PBC patients, Corpechot et al.56 identified LSM cut-offs of 8kPa and 15kPa to stratify patients into low, medium and high-risk categories. Patients in the medium- and high-risk categories exhibited approximately 4-fold and 16-fold higher risks of poor clinical outcomes, respectively, compared to those in the low-risk group. Therefore, this study validated LSM as a major independent predictor of PBC clinical outcomes.56 In addition, the 15kPa threshold is also in line with the Baveno VII recommendations, which suggests using >15kPa as the threshold above which compensated advanced chronic liver disease should be strongly suspected, regardless of etiology.57 Other tools for the evaluation of liver stiffness, including real-time tissue elastography (RTE), shear wave elastography (SWE), and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), have demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance in detecting severe fibrosis and cirrhosis. However, published data evaluating these tools in PBC remain limited.58–61

Beyond TE, prognosis can also be estimated using specific PBC continuous scoring systems. GLOBE score developed by an international multicenter meta-analysis involving 4119 patients with PBC treated with UDCA. The authors identified that age, serum bilirubin, albumin, ALP, and platelet count were independently associated with death or LT. Patients with risk scores>0.30 had significantly shorter TFS compared to matched healthy individuals.62 Another score is the UK-PBC risk score, which was developed using data from a large cohort of patients treated with UDCA. This score, which includes baseline albumin and platelet count, along with bilirubin, transaminases, and ALP levels after 12 months of UDCA therapy, estimates the likelihood of LT or liver-related death within 5, 10, or 15 years. The prognostic performance of both the UK-PBC and GLOBE scores has been validated across different populations in different studies, demonstrating their usefulness as indicators of disease prognosis irrespective of race or ethnicity. In fact, these scores have proven to be better predictors of future cirrhosis-related complications than the classical UDCA response criteria.36

What is the benefit of first-line treatment for patients with PBC? What is the optimal drug and dose of first-line treatment?Recommendations:

- •

Adequate treatment with UDCA in PBC patients has been associated with biochemical improvement and higher TFS. (Statement, consensus 95.6%).

- •

First-line therapy with UDCA at dose of 13–15mg/kg/day should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis of PBC is established. (LoE 1, strong recommendation).

The benefit of UDCA was shown for the first time in a landmark controlled clinical trial by Poupon et al. in 1991, where UDCA treatment for two years showed biochemical improvement and a decrease in IgM in patients with PBC.63 During the open-label phase, patients who received UDCA continuously throughout the entire period experienced slower liver disease progression and reduced need for LT.64 After 10 years of follow-up, the entire cohort demonstrated a higher TFS rate than predicted by the Mayo model. In non-cirrhotic patients, the observed survival was comparable to that of the standardized French population, whereas in cirrhotic patients, it was significantly lower.65 In a US-based randomized clinical trial, patients with PBC receiving UDCA demonstrated better liver-related outcomes and TFS than those receiving placebo. In contrast, a Greek RCT showed no differences in the rates of liver decompensation, liver-related death, or LT.66,67

Since then, UDCA has been extensively studied for its effect on survival and disease progression in patients with PBC. Multiple analyses have highlighted its protective effect against LT and death, particularly when administered at optimal doses and at the early stages of the disease. A comprehensive retrospective analysis of a large registry demonstrated that UDCA had a protective effect against LT or death across all patient groups, except for Caucasian women with an AST/ALT ratio≥1.1.68 Several other studies have supported the role of UDCA in improving the TFS. A meta-analysis of three trials conducted in France, the United States, and Canada demonstrated improved survival in moderate-to-severe PBC cases, particularly in patients with histological stage 4 disease.69,70 Furthermore, a recent multinational cohort study using inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) found that UDCA treatment was associated with better TFS across all biochemical stages, independent of dose or GLOBE score. This association was stronger in patients who received a dose ≥13mg/kg/day.71

Biochemical response to UDCA is a well-established predictor of clinical outcomes in patients with PBC. In this regard, a retrospective analysis showed that patients achieving a biochemical response after one year (defined as a 40% reduction in ALP from baseline) had a survival rate comparable to that of a matched Spanish control population, whereas non-responders exhibited suboptimal survival, identifying them as candidates for additional treatment.72 Similarly, smaller retrospective studies confirmed better outcomes in patients who met the Paris-1 biochemical response criteria.73

Larger cohort studies reinforce the clinical benefit of UDCA, as a study from the Global PBC cohort, which included 3902 patients with a median follow-up of 7.8 years, demonstrated that UDCA significantly reduced the risk of LT or death. The overall hazard ratio (HR) was 0.46, leading to a five-year TFS rate of 81%. The benefits were consistent between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients. Additionally, the effect of UDCA varies based on baseline ALP levels, highlighting the importance of early initiation of UDCA treatment to maximize its efficacy and improve patient adherence.74 The survival benefit of UDCA was further supported by a multicenter retrospective analysis of 526 patients from seven Swedish hospitals. This study found that UDCA responders, as defined by the Paris I criteria, had lower mortality and transplantation rates than non-responders or untreated individuals. However, given the retrospective nature of this study, caution is required when interpreting causality.75

Paris I was further refined into the Paris II criteria. In a study of 165 patients with early-stage PBC, the authors identified that patients whose levels of ALP and AST were less than 1.5 times the ULN, and who had normal bilirubin, experienced no adverse liver-related events over a 7-year follow-up, making these markers strong indicators of favorable prognosis. In contrast, all adverse events such as cirrhosis progression or transplantation occurred in non-responders. Compared to previous response models, the Paris II criteria showed the highest specificity and positive predictive value in early PBC, distinguishing low-risk patients.76 Another retrospective study, focusing on histology progression, showed that 80% of patients who failed to achieve an ALP level below 1.67×ULN after two years of treatment progressed in fibrosis stage. Furthermore, ductopenia observed in more than 50% of portal tracts on initial biopsy was strongly associated with both poor treatment response and fibrosis advancement.77

Finally, in terms of dosing, different studies have examined the optimal UDCA dose range. PBC patients randomized to receive doses between 5 and 20mg/kg/day showed lower benefits at doses below 13mg/kg/day, whereas doses exceeding 15mg/kg/day did not provide additional advantages. Consequently, the preferred dosage range is 13–15mg/kg/day.78

Should normalization of blood tests (ALP, bilirubin, AST) be sought after one year of UDCA treatment in patients with PBC? When should the treatment response be evaluated?Recommendations:

- •

Biochemistry normalization is the ideal endpoint treatment for PBC, but it is currently achievable in less than 20–25% at 1 year of treatment. (Statement, consensus 95.6%).

- •

Biochemical response in PBC should be assessed following 12 months of UDCA treatment. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

Treatment response can be evaluated earlier (after 1–6 months) in high-risk patients. (LoE 4, weak recommendation).

The achievement of normalization of biochemical markers (deep response), particularly ALP and bilirubin (<0.6×ULN), is associated with improved clinical outcomes and reduced progression of liver disease.79 In addition, ALP normalization alone has also been associated with the best survival outcomes. However, attaining these goals may be challenging and not feasible for all patients. Therefore, prioritizing these targets in high-risk groups, such as younger patients (under 62 years) and those with a LSM≥10kPa, is recommended.79 The advantage of achieving normalization of ALP is particularly significant in this population, as its normalization was associated with an absolute increase of 52.8 months in 10-year complication-free survival compared to those who achieved treatment response according to Paris II criteria.

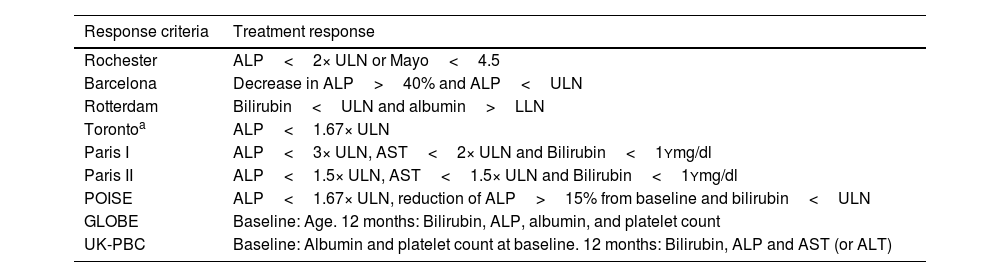

In general, the assessment of treatment response in PBC should occur one year following the initiation of UDCA. Several categorical criteria have been used to evaluate response to UDCA, including Rochester,80,81 Barcelona,72 Paris I and II,76,82 Rotterdam,83 and Toronto77 criteria (Table 2). Although these response systems were developed and validated in diverse clinical settings, they offer a binary classification of treatment response, distinguishing between responders and non-responders. According to these criteria, approximately 40% of patients are classified as non-responders. On the other hand, there are continuous scoring systems, specifically the GLOBE and the UK-PBC score, described previously, which allow for a more refined prognostic stratification. Unlike categorical criteria, these models integrate both biochemical parameters and clinical variables, assessed at baseline and 12 months after treatment initiation. In routine clinical practice, however, the Paris II criteria are the most used, due to their simplicity, intuitive application, and demonstrated better fit for early-stage patients, who currently represent the majority of newly diagnosed PBC cases.

Treatment response criteria in PBC.

| Response criteria | Treatment response |

|---|---|

| Rochester | ALP<2× ULN or Mayo<4.5 |

| Barcelona | Decrease in ALP>40% and ALP<ULN |

| Rotterdam | Bilirubin<ULN and albumin>LLN |

| Torontoa | ALP<1.67× ULN |

| Paris I | ALP<3× ULN, AST<2× ULN and Bilirubin<1Ymg/dl |

| Paris II | ALP<1.5× ULN, AST<1.5× ULN and Bilirubin<1Ymg/dl |

| POISE | ALP<1.67× ULN, reduction of ALP>15% from baseline and bilirubin<ULN |

| GLOBE | Baseline: Age. 12 months: Bilirubin, ALP, albumin, and platelet count |

| UK-PBC | Baseline: Albumin and platelet count at baseline. 12 months: Bilirubin, ALP and AST (or ALT) |

Although treatment response is generally recommended to be assessed at 12 months after initiating UDCA, early evaluation may be particularly beneficial for optimizing management and improving long-term outcomes in high-risk patients. In a retrospective analysis of the Global PBC cohort, an ALP threshold of 1.9×ULN at 6 months of UDCA initiation identified 90% of non-responders according to POISE criteria,84 suggesting that these patients may be candidates for an early initiation of second line drugs.

A new criterion for evaluating UDCA responses at 1 month (ALP≤2.5× ULN and AST≤2× ULN, and total bilirubin ≤1× ULN, Xi’an criteria) predicted the 5-year adverse outcome-free survival rate of UDCA responders versus non-responders (97% vs. 64%). The accuracy of the Xi’an criteria in distinguishing high-risk patients was confirmed in both early- and late-stage PBC85; however, the usefulness of these new criteria must be validated.

What is the treatment for patients with PBC who do not respond to first-line therapy?Recommendation:

- •

Elafibranor, seladelpar and bezafibrate (off-label) can be used in patients with insufficient response or intolerance to UDCA (LoE 1, strong recommendation).

Following the withdrawal of obeticholic acid (OCA) from the European market, three drugs remain available for the management of patients with PBC who exhibit an insufficient response to or intolerance of UDCA: bezafibrate, elafibranor, and seladelpar. These three agents act as agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), a family of nuclear receptors that play a crucial role in regulating bile acid homeostasis by inhibiting bile acid synthesis, promoting bile acid secretion, reducing bile acid toxicity, and facilitating bile acid detoxification.

Bezafibrate, a pan-PPAR agonist, was evaluated for efficacy in the BEZURSO trial,86 a multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial that randomly assigned 100 patients with inadequate response to UDCA to receive either bezafibrate at a daily dose of 400mg (50 patients) or placebo (50 patients). After 24 months of treatment, 31% of patients in the bezafibrate group achieved complete biochemical response, defined as normalization of bilirubin, ALP, aminotransferases, albumin, and prothrombin time, compared to 0% in the placebo group, and 67% achieved ALP normalization. In terms of safety and tolerability, two patients in each group experienced complications related to end-stage liver disease. Creatinine levels increased by 5% from baseline in the bezafibrate group, whereas it decreased by 3% in the placebo group. Myalgia was reported in 20% of patients in the bezafibrate group and in 10% of those in the placebo group. However, the body of evidence supporting the use of bezafibrate extends beyond the BEZURSO trial. In this context, a retrospective study from Japan demonstrated that the addition of bezafibrate to UDCA significantly improved long-term prognosis by reducing all-cause and liver-related mortality and the necessity for LT.87 Despite these promising outcomes, bezafibrate is not approved for the management of PBC, and its use for this indication remains off-label.

Recently, elafibranor, a dual α and δ PPAR agonist, has been approved as a second-line therapy for PBC based on the findings of the ELATIVE trial.1 In this study, 161 patients were randomized to receive either 80mg of elafibranor once daily or placebo. A treatment response, defined as ALP level<1.67× ULN with a reduction of at least 15% from baseline and normal total bilirubin levels, was observed in 51% of patients receiving elafibranor compared to 4% in the placebo group after 52 weeks of treatment. ALP normalization was achieved in 15% of patients in the elafibranor group, whereas no patients in the placebo group reached this endpoint. A key secondary endpoint of the trial was the change in pruritus through week 24 and 52, assessed using the Worst Itch Numerical Rating Scale (WI-NRS) in patients with moderate-to-severe baseline pruritus. This endpoint was not met, as elafibranor did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in pruritus in the WI-NRS scale. In terms of safety and tolerability, elafibranor was associated with mild adverse effects (96% of any adverse event emerging during treatment period vs. 91% in the placebo group), including abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Serious adverse events occurring during the treatment period were reported in 10% of patients in the elafibranor arm, compared to 13% in the placebo arm.

The efficacy of seladelpar, a selective PPAR δ agonist, was evaluated in the RESPONSE trial.2 This phase 3 clinical trial involved the randomization of 193 patients to receive either 10mg of seladelpar daily or placebo in a 2:1 ratio. A biochemical response, based on the same criteria used in the ELATIVE trial, was achieved by 62% of patients on seladelpar and 20% on placebo. ALP normalization occurred in 25% of patients treated with seladelpar, while none in the placebo group achieved this endpoint. A key secondary endpoint was the change from baseline in the weekly mean pruritus NRS score at month 6 among patients with moderate-to-severe pruritus (NRS≥4). Seladelpar significantly reduced pruritus compared to placebo. In terms of safety and tolerability, adverse events were reported in 86.7% of patients in the seladelpar group and 84.6% in the placebo group, with serious adverse events occurring in 7.0% and 6.2% of patients, respectively.

Currently, there are no head-to-head studies comparing the efficacy and safety of the 3 alternatives, and therefore it is not possible to recommend one drug over the other (Fig. 2). Real world data are needed to determine the best patient profile for each drug. Patients previously treated with OCA or bezafibrate can be treated with one of the new PPAR agonists (similar efficacy and safety as those without a previous second line treatment) but the evidence is very limited and comes from a sub-analysis of the clinical trials presented in abstract form.88

Algorithm for the management of patients with PBC. Response evaluation at one year of treatment can be performed using different validated response criteria, with the most commonly used being the Paris II and POISE criteria. Patients presenting an ALP level greater than 1.9 times the upper limit of normal (× ULN) at 6 months have a low probability of achieving a POISE response at one year. In such cases, the early initiation of a second-line therapy may be considered on an individual basis. * Bezafibrate is not approved for the indication of PBC at the time of writing this document.

In a press release issued in August 2025, a phase IIb/III clinical trial revealed that saroglitazar achieved the primary composite endpoint, exhibiting a 48.5% treatment difference in biochemical response compared to placebo (p<0.001).89 At the time of these guidelines’ publication, no further trial data were available.

The addition of OCA and bezafibrate to UDCA (also known as triple therapy) has shown excellent results in patients with insufficient response to UDCA in the preliminary report of a randomized controlled trial conducted in several countries around the world with ALP normalization and biochemical remission rates at 24 weeks of treatment of 61.1% and 66.7%,90 respectively. In addition, real world observational studies have also shown good results of the triple therapy in patients who failed second line therapy to OCA or bezafibrate. However, after revocation of OCA commercialization in Europe, the use of this combination in real-world clinical practice is rapidly declining, as OCA is no longer being supplied to treatment centers except in exceptional cases individually evaluated by the Spanish Medicines Agency.

Should patients with PBC-related cirrhosis be screened for HCC?Recommendation:

- •

Ultrasound screening for HCC every 6 months is recommended for patients with PBC when cirrhosis is established. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

Patients with PBC are at risk of developing HCC and this risk increases as histological damage progresses.91,92 The estimated incidence of HCC in patients with PBC is 0.36 per 100 patient-years and is higher in men and in patients with advanced disease, at a rate of 3.4 cases per 1000 patient-years.43,93 In addition to male sex, diabetes mellitus, HBV infection, and lack of response to UDCA also increase the risk of developing HCC.93–96 Suboptimal response to UDCA is also a significant risk factor, although UDCA treatment and response do not prevent this risk in patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, risk stratification is very important, as male non-responders to UDCA without advanced disease have a higher risk of developing HCC than women with UDCA-responsive cirrhosis.93 Therefore, regular HCC screening with ultrasound evaluation every six months is recommended, especially in men and patients with cirrhosis.92,97,9899–104 In male patients without cirrhosis, the recommendation for semiannual HCC surveillance may be considered on an individual basis.

Which patients with PBC should be screened for esophagogastric varices?Recommendation:

- •

Screening for esophagogastric varices using upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is recommended for patients with PBC and established cirrhosis. (LoE 1, strong recommendation).

- •

When cirrhosis is not clearly established, LSM, spleen stiffness measurement and platelet count can help in determining the need for esophagogastric varices screening. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

PH can develop as a result of established biliary cirrhosis or, in the pre-cirrhotic phase, in conjunction with nodular regenerative hyperplasia. It often manifests during the early stages of the disease.8,46 However, approximately one-third of patients with advanced disease develop varices within a mean of 5.6 years. In this regard, patients who respond to UDCA exhibit an improvement in PH.105 The AASLD,106 EASL guidelines,107 and the different Baveno Consensus meetings57,108 provide recommendations for the management of esophagogastric varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients, which are also applicable to individuals with PBC.109 Moreover, different efforts have been made to identify noninvasive markers predictive of the presence of esophagogastric varices,110–113 underscoring the need for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for variceal detection. Current strategies rely on platelet counts and TE as criteria for endoscopic surveillance.114 Specifically, the Baveno VI and VII guidelines recommend incorporating criteria, such as LSM>20kPa or platelet counts<150,000/mm3. However, it is important to note that patients with PBC were underrepresented in these studies.38 In addition, a recently published study, found that the presence of cholestasis defined by the presence of an ALP>1.5× ULN increases the possibility of missing high-risk varices by the Baveno and expanded Baveno criteria115 complicating even more the applicability of these guidelines in PBC patients. In some cases, spleen stiffness values greater than 40kPa may also be useful as a cut-off point to indicate upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

It is important to emphasize that PH in PBC can develop early in the course of the disease, signaling an increased risk of hepatic decompensation and mortality. Consequently, risk stratification is key to identifying patients who may benefit from screening endoscopy.116 Furthermore, beyond its role in assessing the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, the detection of esophagogastric varices may have additional prognostic significance even in the absence of cirrhosis, as some studies suggest an increased risk of HCC in patients with PBC and varices, further underscoring the importance of early identification and screening.117

When is LT indicated for patients with PBC?Recommendations:

- •

LT should be considered for patients with PBC who meet standard criteria, such as decompensation and/or HCC. Additionally, LT is indicated for those exhibiting poor prognostic markers, including serum bilirubin levels exceeding 6mg/dl or a Mayo Risk Score greater than 7.8. (LoE 2, strong recommendation).

- •

LT should be considered in selected patients with PBC who experience severe, refractory pruritus unresponsive to medical therapy, even in the absence of hepatic decompensation or HCC. (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

LT is not recommended for patients with PBC on the basis chronic fatigue in the absence of hepatic decompensation or HCC, as fatigue typically persists after transplantation. (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

In terms of survival and quality of life, LT is the most effective treatment for end-stage liver disease related to PBC (patient survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years are 90%, 86%, and 84%, respectively).118 Nevertheless, PBC accounts for only approximately 2–6% of all LT, representing an almost 50% reduction over the past 25 years. This decline is primarily due to significant advancements in clinical management and the introduction of new therapeutic options.119,120

LT in PBC follows the general indications established for other causes of cirrhosis (decompensation and/or HCC). However, serum bilirubin level or Mayo Risk score exceeding 6mg/dl or 7.8, respectively, are considered special risk factors for PBC.121–123 Mayo risk score was the first in identifying the main risk factors for mortality in patients with PBC, and constituted an indication for LT based on age, bilirubin and albumin levels, prothrombin time and presence of edema.

It is widely accepted that patients with PBC with first decompensation and/or MELD scores>15 should be promptly considered for LT. PBC patients face a relative disadvantage in access to LT compared to those with other etiologies, because of higher waitlist mortality and lower transplantation rates. Prioritization on the LT waiting list based on the MELD score disadvantages patients with PBC, due to gender-related bias and the inconsistent recognition of refractory pruritus as a valid indication for transplantation.120,124 New models such as MELD 3.0, and GEMA-Na can amend this inequity125 but further validation of these scores in PBC patients is needed.

Should UDCA be used to prevent post-transplant PBC recurrence? Is there any benefit of an immunosuppression scheme in the prevention of PBC recurrence after LT?Recommendations:

- •

It is recommended to initiate preemptive treatment with UDCA at 10–15mg/kg/day after LT in patients with PBC, as it is associated with a reduced risk of disease recurrence and improved graft and patient survival. (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

- •

No universal immunosuppressive regimen can be specifically recommended for PBC patients undergoing LT. (LoE 3, weak recommendation).

The first report of PBC recurrence after LT was published by Neuberger et al.126 Based on a longer follow-up period, several studies have described recurrence rates ranging from 10 to 61%, with limited impact on graft and patient survival.127–129 Variability in diagnostic criteria, different follow-up times, and immunosuppressive treatments are responsible for the discrepancy in recurrence rates.129 Nevertheless, graft failure, re-transplantation, and death secondary to PBC recurrence have been reported in the literature.

Because symptoms and biochemical liver tests are non-specific and AMA persists after LT, the diagnosis must be based on liver biopsy, excluding other causes of graft dysfunction. Histological features of PBC recurrence in the graft include lymphoplasmacytic portal inflammation, lymphoid aggregates, epithelioid granulomas and evidence of bile duct injury.129,130

Several risk factors have been associated with post-liver transplant recurrence of PBC, including recipient and donor age, serum immunoglobulin M levels, HLA-DR mismatch, immunosuppression regimen (tacrolimus vs. cyclosporine), and persistent biochemical cholestasis after transplantation.120 A systematic review and meta-analysis including six retrospective studies of 3184 patients who underwent LT for PBC showed that recurrence was diagnosed in 935 (29.4%) patients, indicating that the use of tacrolimus and preventive UDCA were risk and protective factors, respectively.131 In this regard, a retrospective multicenter cohort study conducted by the Global PBC Study Group, which included 780 patients who underwent LT for PBC between 1983 and 2017, assessed disease recurrence based on histological evidence. The study found that the preventive use of UDCA and cyclosporine as immunosuppressive agents was associated with the lowest risk of recurrence and mortality.132 In another meta-analysis involving 1727 patients, Pedersen et al. demonstrated the protective effect of UDCA in preventing PBC recurrence after LT.133 However, regarding the immunosuppressive regimen, several previous studies have reported that the choice between cyclosporine and tacrolimus does not influence recurrence rates.134,135

Currently, there are no clear guideline recommendations regarding immunosuppressive regimens for PBC recurrence prevention. When selecting between cyclosporine and tacrolimus, it is essential to consider their potential side effects, including risks of acute and chronic rejection, infection, and renal dysfunction. Therefore, treatment decisions should be made on an individualized basis, weighing the benefits and risks of each regimen.136

How is PBC/AIH variant diagnosed?Recommendation:

- •

The Paris criteria remain the best-validated and guideline-endorsed system for diagnosing PBC/AIH variant. However, Zhang score may offer improved sensitivity in milder presentations (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

A Zhang scoring system>21 should prompt the diagnosis of PBC-AIH variant (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

PBC and AIH are distinct clinical entities characterized by specific biochemical, histological and serological profiles.137,138 However, there is a group of patients with features of both AIH and PBC at diagnosis139–141 or after several years of an initial diagnosis of PBC142–144 or AIH.142

The Paris criteria is the most commonly used tool for diagnosing variant syndrome (VS), formerly known as PBC/AIH overlap syndrome.145 This requires the presence of at least two of three key criteria for the diagnosis of PBC and AIH. Thus, for PBC, the criteria are as follows: (1) ALP>2× ULN or GGT>5× ULN; (2) positive AMA; and (3) liver biopsy specimen showing florid bile duct lesions. For AIH, the criteria are as follows: (1) ALT levels>5× ULN; (2) serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels>2× ULN or positive anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs); and (3) liver biopsy showing moderate or severe interface hepatitis. The 2009 EASL guidelines for the management of cholestatic liver diseases endorsed the Paris criteria while emphasizing that histologic evidence of moderate to severe interface hepatitis is essential for the diagnosis of VS.146 The reported sensitivity and specificity of the Paris criteria for VS are 92% and 97%, respectively.145 The reported sensitivity and specificity of the Paris criteria for VS are 92% and 97%, respectively.147,148 Furthermore, during the natural progression of PBC, all untreated patients develop interface hepatitis within four years, and a considerable proportion demonstrate positive ANA and/or ASMA at diagnosis.149 These findings indicate that meeting the diagnostic standards for PBC combined with significant interface hepatitis and presence of ANA and/or ASMA does not suffice to define VS.

The International AIH Group (IAIHG) scoring system for AIH is another widely used diagnostic criterion for the diagnosis of VS, although it was not intended for such use and has not proven to be an efficient tool for this purpose.139 The diagnostic criteria for AIH were initially introduced by the IAIHG in 1993 and later revised in 1999.43,150 The revised IAIHG scoring system was able to identify 19% of AIH variant when applied to 137 patients diagnosed with PBC.151,152 The IAIHG suggests that patients with autoimmune liver disease should be categorized according to their predominant features and that patients with variant features should not be considered distinct diagnostic entities.

Consequently, there is a pressing need for the development of novel diagnostic criteria capable of detecting both typical and mild VS with high sensitivity and specificity. This is of paramount importance, as research indicates that patients with VS may experience poorer clinical outcomes compared to those with PBC alone, including an earlier onset of PH and an increased likelihood of requiring LT.149 To overcome these limitations a new scoring system for the identification of VS has been recently developed by modifying the IAIHG revised criteria.151 The “Zhang criteria” score integrates the histological features of AIH and PBC, alongside modifications in biochemical and immunological characteristics. The optimal diagnostic performance for VS was observed in patients with a score of ≥21, yielding a sensitivity of 98.5%, specificity of 92.8%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 81.0%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.5%. All individuals diagnosed with VS had an aggregate score exceeding 19, whereas the majority of patients with PBC or AIH scored below 19, establishing this as an effective discriminatory threshold against VS. In assessing the sensitivity of the Paris criteria for diagnosing VS within this cohort, the sensitivity was 58.46%, specificity was 99.52%, PPV was 97.44%, and NPV was 88.41%. Compared to the Paris criteria, the Zhang diagnostic criteria, with a cut-off score of 21, demonstrated superior sensitivity and NPV but lower specificity and PPV. This classification method appears to accurately identify patients with VS and may surpass existing scoring systems, including the revised and simplified AIH scores and the Paris criteria, in detecting VS and its milder forms. However, the Zhang criteria were developed in a study by Zhang et al. that included a limited sample size from a single center, necessitating further studies to assess its validity. Despite the enhanced precision of Zhang's criteria, variant forms remain difficult to classify. A retrospective study evaluating patients diagnosed with VS revealed that only 24% met the Paris criteria and only 70% met Zhang's criteria, indicating that current classification tools are suboptimal. Furthermore, a significant finding of the study was that patients who did not meet the VS criteria and were not treated with combined immunosuppressive therapy and UDCA, but exhibited analytical markers of inflammation (defined as ALT or AST>2.5× ULN and elevated IgG), had a poorer prognosis than those classified as VS who received treatment, even if they did not meet the Paris or Zhang criteria.153

Autoantibodies, particularly anti-dsDNA, have been proposed as useful non-invasive markers for identifying patients with VS,138 given their higher prevalence in VS compared to PBC alone. Finally, a recent study developed two artificial intelligence-based predictive models using serological data from 201 biopsy-proven cases of autoimmune liver disease.137 Showing the potential utility of IgG, IgM, anti-Sp100, anti-Ro-52, anti-SSA, ANA, partial thromboplastin time and α-fetoprotein as additional discriminative variables for diagnosing VS. However, these results need further evaluation and external validation.

What are the most frequently associated symptoms in PBC? How should they be assessed? What therapeutic alternatives are available?

Recommendations:

- •

In patients with PBC, the presence and severity of pruritus and fatigue should be assessed at every clinical visit (LoE 4, strong recommendation).

- •

Bezafibrate is the recommended first line treatment of moderate-to-severe pruritus (LoE 2, strong recommendation).

- •

Ileal bile acid transporters inhibitors should be considered as an alternative to bezafibrate, particularly in patients with well-controlled disease (LoE 2, strong recommendation).

- •

In the management of fatigue, aerobic and resistance physical exercise is recommended as a non-pharmacological intervention (LoE 3, strong recommendation).

Pruritus is a highly prevalent symptom in patients with PBC, affecting up to 70–80% of them at some point during the disease course. Nevertheless, its expression varies greatly, as some patients experience mild and intermittent itching, while others suffer from severe, chronic pruritus that significantly impairs quality of life. Importantly, pruritus may occur even in early-stage or biochemically well-controlled PBC and does not necessarily correlate with liver enzyme levels or histological activity.

The pathogenesis of cholestatic pruritus in PBC is not completely understood. A key mechanism involves the accumulation of BA and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA),154 produced by the enzyme autotaxin. These compounds are believed to stimulate pruritogenic receptors on cutaneous and sensory neurons. The G-protein-coupled receptor MRGPRX4 has emerged as a likely candidate mediating bile acid-induced itch.155 Additionally, elevated endogenous opioids and an imbalance in μ- and κ-opioid receptor activity are thought to modulate central itch perception. Other contributors may include bilirubin, histamine-independent pathways, and neural sensitization, particularly in chronic cases.156 However, the relative roles of these mediators remain debated, and not all patients with high levels of BA or autotaxin experience pruritus, suggesting a complex interplay of mechanisms.

As the prevalence of pruritus is very high, an adequate evaluation of pruritus and its impact on quality of life is of critical importance. The most used tools include the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), where patients rate their itch intensity on a scale from 0 (no itch) to 10 (worst imaginable itch). Multidimensional tools such as the 5-D Itch Scale (assessing duration, degree, direction, disability, and distribution)157 and disease-specific instruments like the PBC-40 questionnaire provide a broader evaluation, incorporating the impact of pruritus on quality of life, sleep, and emotional well-being.158