Although patients with advanced liver disease have been included in studies evaluating fibrates for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), the frequency of biochemical responses and adverse effects for this group of patients was not reported separately and comprehensively.

Aimsto evaluate the efficacy and safety of additional fenofibrate therapy in patients with advanced and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)-refractory PBC.

MethodsPatients were analyzed retrospectively to determine the clinical therapeutic effects of UDCA with additional fenofibrate therapy versus continued UDCA monotherapy. The liver transplantation (LT)-free survival and the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) normalization rates were estimated using Cox regression analyses and Kaplan–Meier plots with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW).

ResultsA total of 118 patients were included: 54 received UDCA alone and 64 received UDCA in combination with fenofibrate therapy. In the fenofibrate and UDCA groups, 37% and 11% of patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC, respectively, achieved ALP normalization (P=0.001). Additional fenofibrate therapy improved both LT-free survival and ALP normalization rate after IPTW (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.07–0.75, P=0.015; and HR: 11.66, 95% CI: 5.02–27.06, P=0.001, respectively). These effects were supported by parallel changes in the rates of liver decompensation and histologic progression, and the United Kingdom (UK)-PBC and Globe risk scores. During the follow-up period, serum levels of ALP and aminotransferase decreased significantly, while total bilirubin, albumin, platelet, serum creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate remained stable in fenofibrate-treated participants. No fenofibrate-related significant adverse events were observed in our cohort.

ConclusionsAdditional fenofibrate therapy significantly improved LT-free survival and ALP normalization in patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC. Furthermore, adding-on fenofibrate therapy appeared to be safe and well tolerated in this population.

Aunque los pacientes con enfermedad hepática avanzada se han incluido en los estudios que evalúan los fibratos para el tratamiento de la colangitis biliar primaria, la frecuencia de las respuestas bioquímicas y los efectos adversos para este grupo de pacientes no se informó por separado y de forma exhaustiva.

ObjetivosEvaluar la eficacia y la seguridad del tratamiento adicional con fenofibrato en pacientes con colangitis biliar primaria avanzada y refractaria al ácido ursodesoxicólico.

MétodosSe analizaron los pacientes de forma retrospectiva para determinar los efectos terapéuticos clínicos del ácido ursodesoxicólico con terapia adicional de fenofibrato frente a la monoterapia continuada con ácido ursodesoxicólico. La supervivencia sin trasplante de hígado y las tasas de normalización de la fosfatasa alcalina se estimaron mediante análisis de regresión de Cox y gráficos de Kaplan-Meier con ponderación de la probabilidad inversa del tratamiento.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 118 pacientes: 54 recibieron ácido ursodesoxicólico solo y 64 recibieron ácido ursodesoxicólico en combinación con el tratamiento con fenofibrato. En los grupos de fenofibrato y ácido ursodesoxicólico, 37 y 11% de los pacientes con colangitis biliar primaria avanzada y refractaria al ácido ursodesoxicólico, respectivamente, lograron la normalización de la fosfatasa alcalina (p=0,001). El tratamiento adicional con fenofibrato mejoró tanto la supervivencia libre de trasplante de hígado como la tasa de normalización de la fosfatasa alcalina tras la ponderación de la probabilidad inversa del tratamiento (cociente de riesgos: 0,23, intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC 95%]: 0,07-0,75, p=0,015; y cociente de riesgos: 11,66, IC 95%: 5,02–27,06, p=0,001, respectivamente). Estos efectos se vieron respaldados por cambios paralelos en las tasas de descompensación hepática y de progresión histológica, y por las puntuaciones de riesgo de colangitis biliar primaria del Reino Unido y de Globe. Durante el periodo de seguimiento, los niveles séricos de fosfatasa alcalina y aminotransferasa disminuyeron significativamente, mientras que la bilirrubina total, la albúmina, las plaquetas, la creatinina sérica y la tasa de filtración glomerular estimada permanecieron estables en los participantes tratados con fenofibrato. No se observaron acontecimientos adversos significativos relacionados con el fenofibrato en nuestra cohorte.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento adicional con fenofibrato mejoró significativamente la supervivencia libre de trasplante hepático y la normalización de la fosfatasa alcalina en pacientes con colangitis biliar primaria avanzada y refractaria al ácido ursodesoxicólico. Además, el tratamiento adicional con fenofibrato parece ser seguro y bien tolerado en esta población.

Currently, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the only first-line medication approved for the disease-modifying therapy of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).1,2 Long-term UDCA therapy in PBC patients has been shown to improve cholestasis-related indicators, delay histological progression, and prolong survival without liver transplantation (LT).1,2 However, approximately 40% of PBC patients undergoing UDCA treatment do not achieve a biochemical response,3,4 particularly those in an advanced stage at presentation.2 Patients who do not respond adequately to treatment, as well as those with advanced liver disease, should receive additional therapies.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is a farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist approved for the treatment of PBC patients who do not respond adequately to UDCA.2,5 However, when compared to a placebo, OCA has been linked to a higher incidence of severe pruritus.6,7 Alternatively, combining of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists (the fibrates) with UDCA has been shown to have relatively good efficacy and safety in patients with PBC who have failed to respond adequately to other treatments.8–13 Off-label therapy, particularly with fibrates, is recommended for patients who do not respond adequately to UDCA.5 However, there are concerns about the safety profile of these drugs. Fenofibrate has been linked to an increase in bilirubin levels and a negative impact on renal function in patients with advanced PBC.12,14 Furthermore, fenofibrate has been shown to have limited efficacy in cirrhotic patients with reduced biochemical improvements and increased liver-related incidents.12,14 Despite this, only a limited amount of data is available on the frequency of biochemical responses and adverse effects (AEs) in UDCA-refractory patients with advanced PBC.

To address these gaps, we studied 118 patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy profile of add-on fenofibrate therapy based primarily on alkaline phosphatase (ALP) normalization rate and LT-free survival. Our secondary objective was to evaluate the safety of additional fenofibrate treatment through fenofibrate-related symptoms, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity.

MethodsStudy designPatients were divided into “the fenofibrate group” and “the UDCA group” based on whether they received UDCA and fenofibrate combined therapy or UDCA monotherapy. The primary outcome was the efficacy of additional fenofibrate treatment, which was evaluated primarily by ALP normalization rate and LT-free survival. We also calculated the United Kingdom (UK)-PBC risk score,15 the Globe risk score,16 the Mayo risk score,17 and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score to assess the severity of PBC. Dynamic changes in the median levels of serum ALP, albumin (ALB), total bilirubin (Tbil), platelet (PLT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were collected systemically to assess biochemical improvements; these parameters are known to correlate with prolonged LT-free survival.15,16,18–21 The secondary outcome was the safety of additional fenofibrate therapy as evaluated by fenofibrate-related symptoms, nephrotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity. We used the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation22 to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The study design was approved by the ethics committee of the Xijing Hospital of the Air Force Military Medical University. All participants signed written informed consent forms.

Study populationOne hundred and eighteen subjects with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC were diagnosed and treated in Xijing Hospital of Digestive Diseases (Xi’an, Shaanxi, China) from March 2009 to April 2022. PBC was diagnosed when at least two of the following criteria were met: (1) elevated ALP levels, (2) seroreactivity to specific autoantibodies, and (3) suggestive histological data.23 Refractory UDCA was defined as failure to meet the threshold for serum ALP level >1.67×upper limit of the normal range (ULN)18 following at least 6 months of prior UDCA monotherapy. Fenofibrate is added at the diagnosis of UDCA-refractory PBC. If a patient met one of the following criteria, they were diagnosed with advanced liver disease: (1) histology indicating bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis (when a biopsy was available), (2) liver stiffness measurement >9.6kPa (elastography) within 6 months of baseline or (3) at least one abnormal serum levels for either Tbil or ALB.2 The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) concurrent autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, chronic hepatitis B/C, or other liver disease, (2) evidence of liver decompensation, acute liver failure, or kidney disease, or (3) heart failure, malignant conditions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other serious comorbidities. Liver decompensation was defined by the occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, or variceal bleeding. Histological progression was defined as an increase of at least one grade in the stage of fibrosis. The oral doses of fenofibrate and UDCA were 200mg/d and 13–15mg/kg/d, respectively.

Data gathering and analysesBiochemical monitoring, which included blood parameters related to liver function, renal function, and blood count, began at baseline, and was repeated every 3–12 months throughout the study period. Data on demographics, baseline, and follow-up were gathered from medical records; a telephone follow-up was conducted primarily to determine whether the patients had received LT or had died at the end of the study; and biochemical improvements were compared annually and at the end of the study. Histology staging was performed based on a previous study by Ludwig et al.24 Adherence to treatment and AEs were evaluated and documented in the electronic clinical notes at each visit. At the initial evaluation, seven of ten fenofibrate-treated patients and seven of eight UDCA-treated patients were enrolled in the study for histological evidence of bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis; four of five fenofibrate-treated patients and one of three UDCA-treated patients had elastography values greater than 9.6kPa; other patients due to albumin and/or platelet abnormalities.

Statistical analysisQuantifiable variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range (IQR), and compared with the independent-samples t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Qualitative variables were compared by the chi-squared test. The propensity score was computed via logistic regression analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival methods and Cox regression analysis were used to evaluate the LT-free survival and ALP normalization rate; these tests were performed with R statistical software 4.13 (TUNA Team, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China). For comparison purposes, the log-rank test was used, and the hazard ratio (HR) was determined by Cox regression analysis. A bilateral P-value <0.05 was judged to be significant.

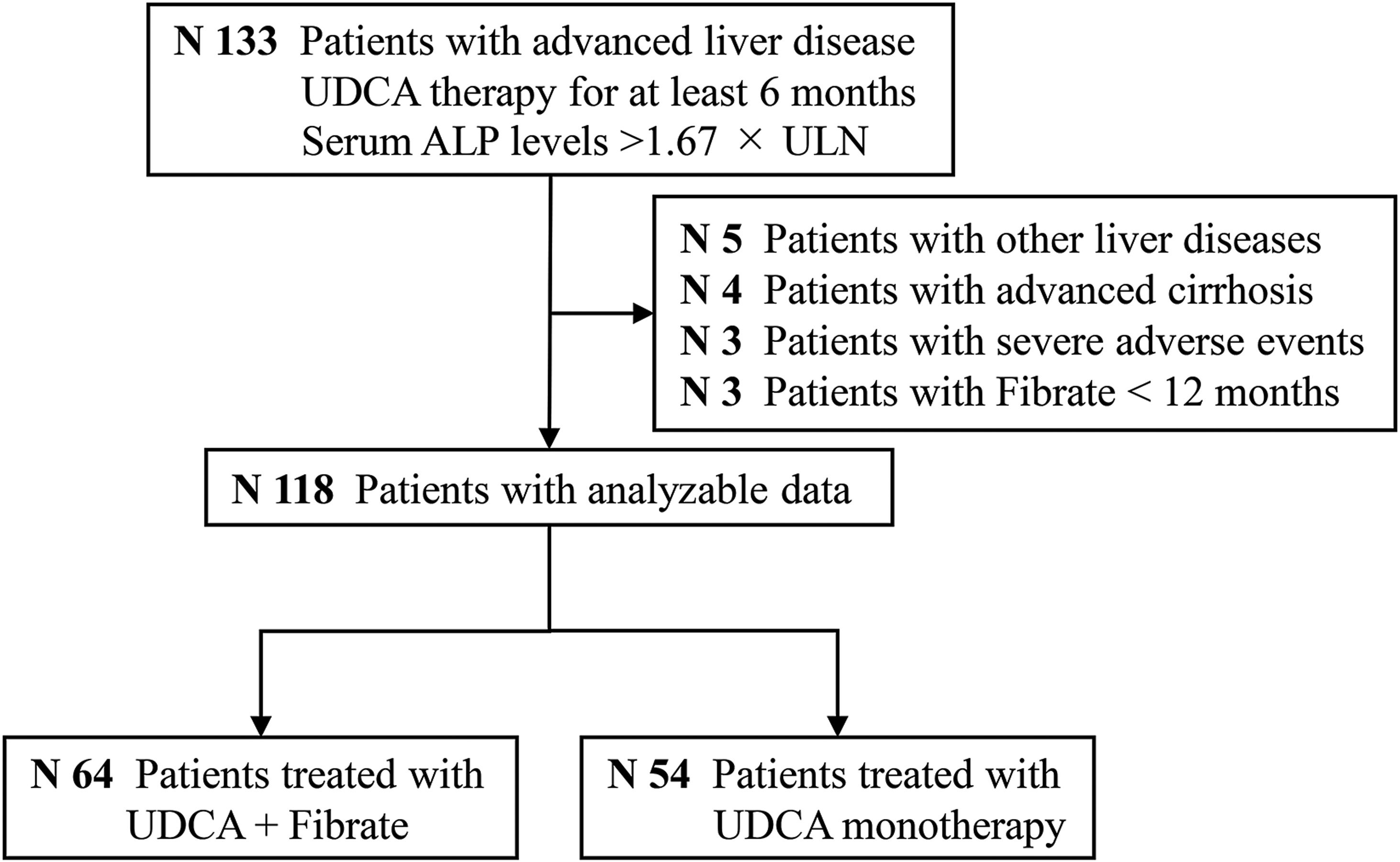

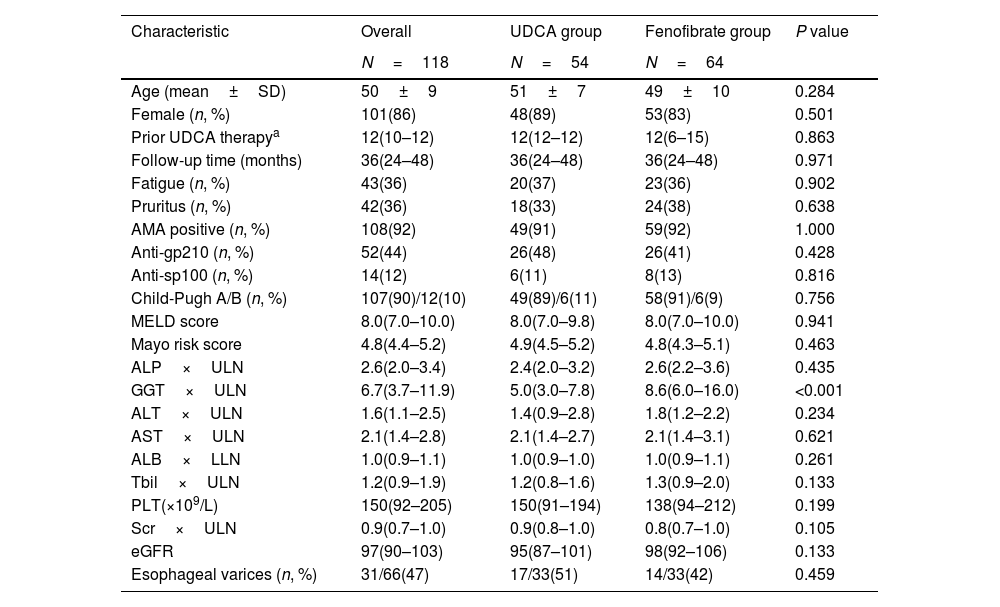

ResultsStudy populationAs shown in Fig. 1, a total of 118 subjects qualified for the primary analysis. Of these participants with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC, 54 (45%) were treated with continuous UDCA monotherapy (the UDCA group), and 64 (55%) were treated with fenofibrate in combination with UDCA (the fenofibrate group). Table 1 summarizes a detailed description of demographic and baseline characteristics of the participants. The mean age of the participants at diagnosis of refractory UDCA was 50±9 years; the majority were female (86%), AMA positive (92%), and classified as Child-Pugh A (90%). The median duration of UDCA treatment prior to adding fenofibrate was 12 months (IQR, 6–15 months). Fenofibrate therapy was used for a median duration of 36 months (range, 12–108 months). The study cohort had a median MELD score of 8.0 and a median Mayo risk score of 4.8, respectively. Except for serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels (P<0.001), there were no significant differences between the two groups at baseline.

Baseline characteristics of patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory primary biliary cholangitis between “the UDCA group” and “the fenofibrate group”.

| Characteristic | Overall | UDCA group | Fenofibrate group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=118 | N=54 | N=64 | ||

| Age (mean±SD) | 50±9 | 51±7 | 49±10 | 0.284 |

| Female (n, %) | 101(86) | 48(89) | 53(83) | 0.501 |

| Prior UDCA therapya | 12(10–12) | 12(12–12) | 12(6–15) | 0.863 |

| Follow-up time (months) | 36(24–48) | 36(24–48) | 36(24–48) | 0.971 |

| Fatigue (n, %) | 43(36) | 20(37) | 23(36) | 0.902 |

| Pruritus (n, %) | 42(36) | 18(33) | 24(38) | 0.638 |

| AMA positive (n, %) | 108(92) | 49(91) | 59(92) | 1.000 |

| Anti-gp210 (n, %) | 52(44) | 26(48) | 26(41) | 0.428 |

| Anti-sp100 (n, %) | 14(12) | 6(11) | 8(13) | 0.816 |

| Child-Pugh A/B (n, %) | 107(90)/12(10) | 49(89)/6(11) | 58(91)/6(9) | 0.756 |

| MELD score | 8.0(7.0–10.0) | 8.0(7.0–9.8) | 8.0(7.0–10.0) | 0.941 |

| Mayo risk score | 4.8(4.4–5.2) | 4.9(4.5–5.2) | 4.8(4.3–5.1) | 0.463 |

| ALP×ULN | 2.6(2.0–3.4) | 2.4(2.0–3.2) | 2.6(2.2–3.6) | 0.435 |

| GGT×ULN | 6.7(3.7–11.9) | 5.0(3.0–7.8) | 8.6(6.0–16.0) | <0.001 |

| ALT×ULN | 1.6(1.1–2.5) | 1.4(0.9–2.8) | 1.8(1.2–2.2) | 0.234 |

| AST×ULN | 2.1(1.4–2.8) | 2.1(1.4–2.7) | 2.1(1.4–3.1) | 0.621 |

| ALB×LLN | 1.0(0.9–1.1) | 1.0(0.9–1.0) | 1.0(0.9–1.1) | 0.261 |

| Tbil×ULN | 1.2(0.9–1.9) | 1.2(0.8–1.6) | 1.3(0.9–2.0) | 0.133 |

| PLT(×109/L) | 150(92–205) | 150(91–194) | 138(94–212) | 0.199 |

| Scr×ULN | 0.9(0.7–1.0) | 0.9(0.8–1.0) | 0.8(0.7–1.0) | 0.105 |

| eGFR | 97(90–103) | 95(87–101) | 98(92–106) | 0.133 |

| Esophageal varices (n, %) | 31/66(47) | 17/33(51) | 14/33(42) | 0.459 |

The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data.

Depending on the normality of the distribution (non)parametrical tests were used to compare continuous data.

UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALB, albumin; Tbil, total bilirubin; PLT, platelet; Scr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MELD score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score; ULN, upper limit of the normal range; LLN, lower limit of the normal range; SD, standard deviation.

Data is expressed as median and interquartile range.

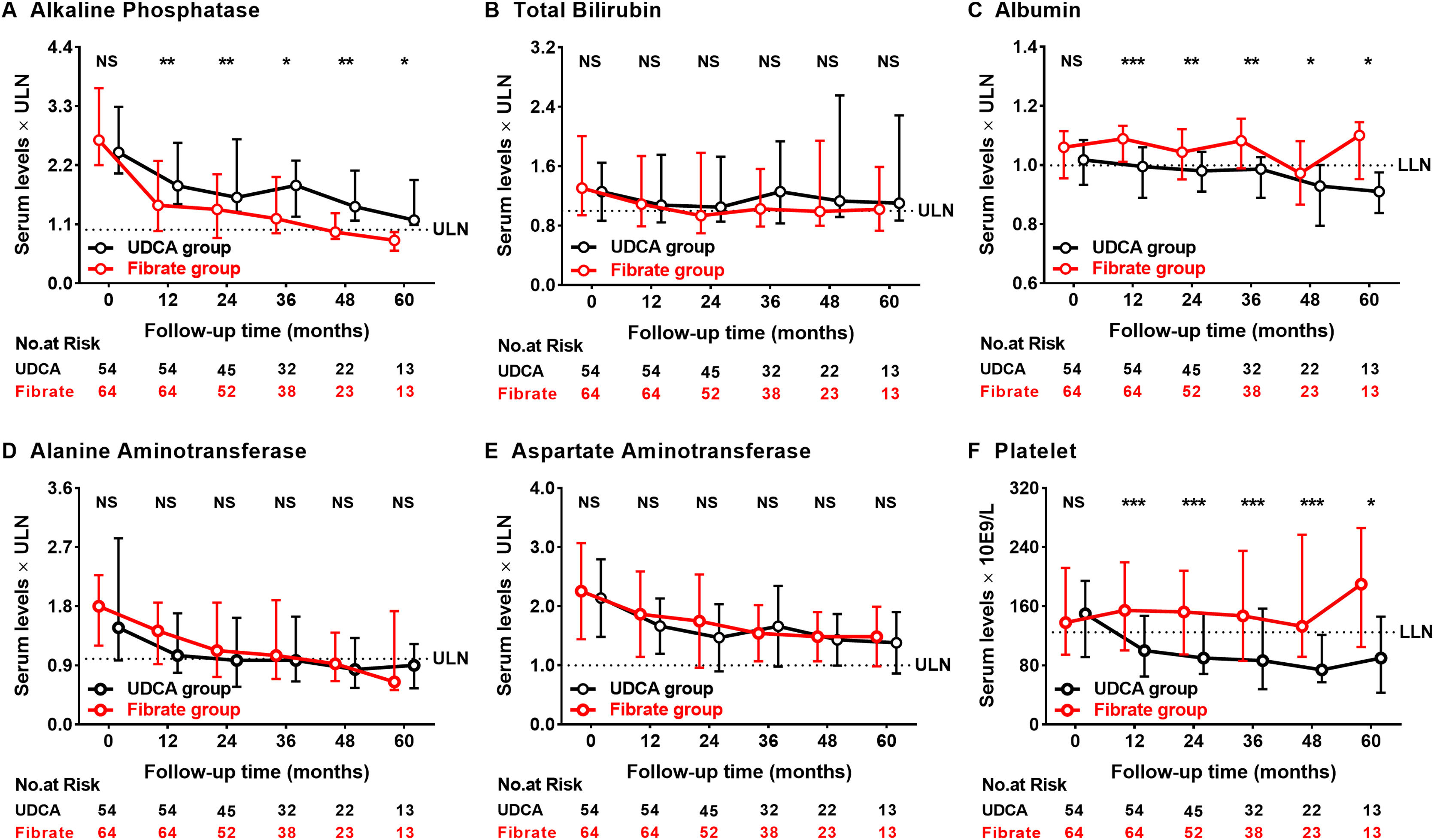

Fig. 2 demonstrates specific improvements in serum levels of ALP, Tbil, ALB, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST, and PLT. Within the first 12 months of fenofibrate initiation, the median level of serum ALP improved significantly, with a 45% reduction from baseline compared to only 25% of the UDCA-treated patients (P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively). More importantly, the beneficial effects of fenofibrate therapy on ALP levels persisted even after 60 months. At 60 months, the serum levels of ALB and PLT were 10% and 40% lower in those treated with UDCA monotherapy, respectively (P=0.004 and 0.023); the levels of ALT and AST decreased progressively in both groups during follow-up (P<0.01 for both parameters). Significant improvements were observed in the medial levels of ALP, ALB, and PLT in the fenofibrate-treated participants when compared to those treated with UDCA. Elevated ALP levels were observed in four participants after discontinuing fenofibrate but not UDCA for 0.33–3 months; two of the four participants achieved ALP normalization after resuming fenofibrate therapy (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The dynamic changes of alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, albumin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and platelets according to follow-up time between the UDCA group and the Fibrate group. Shown are the median values and interquartile ranges at each follow-up visit. Data was compared with the Mann–Whitney U test (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS, no significance).

UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; Fibrate, fenofibrate; ULN, upper limit of the normal range; LLN, lower limit of the normal range.

Abnormal serum Tbil level has been found to be a factor of poor prognosis of PBC, and Tbil >30μmol/L can increase the incidence of liver transplantation or death by 6-fold.25 At baseline, Tbil >30μmol/L was observed in seventeen (31%) UDCA-treated and twenty-two (34%) fenofibrate-treated participants (P=0.739). During follow-up, two (12%) UDCA-treated and nine (41%) fenofibrate-treated participants had remission of Tbil <30μmol/L (P=0.100); fourteen (38%) UDCA-treated and ten (24%) fenofibrate-treated participants developed Tbil >30μmol/L (P=0.176).

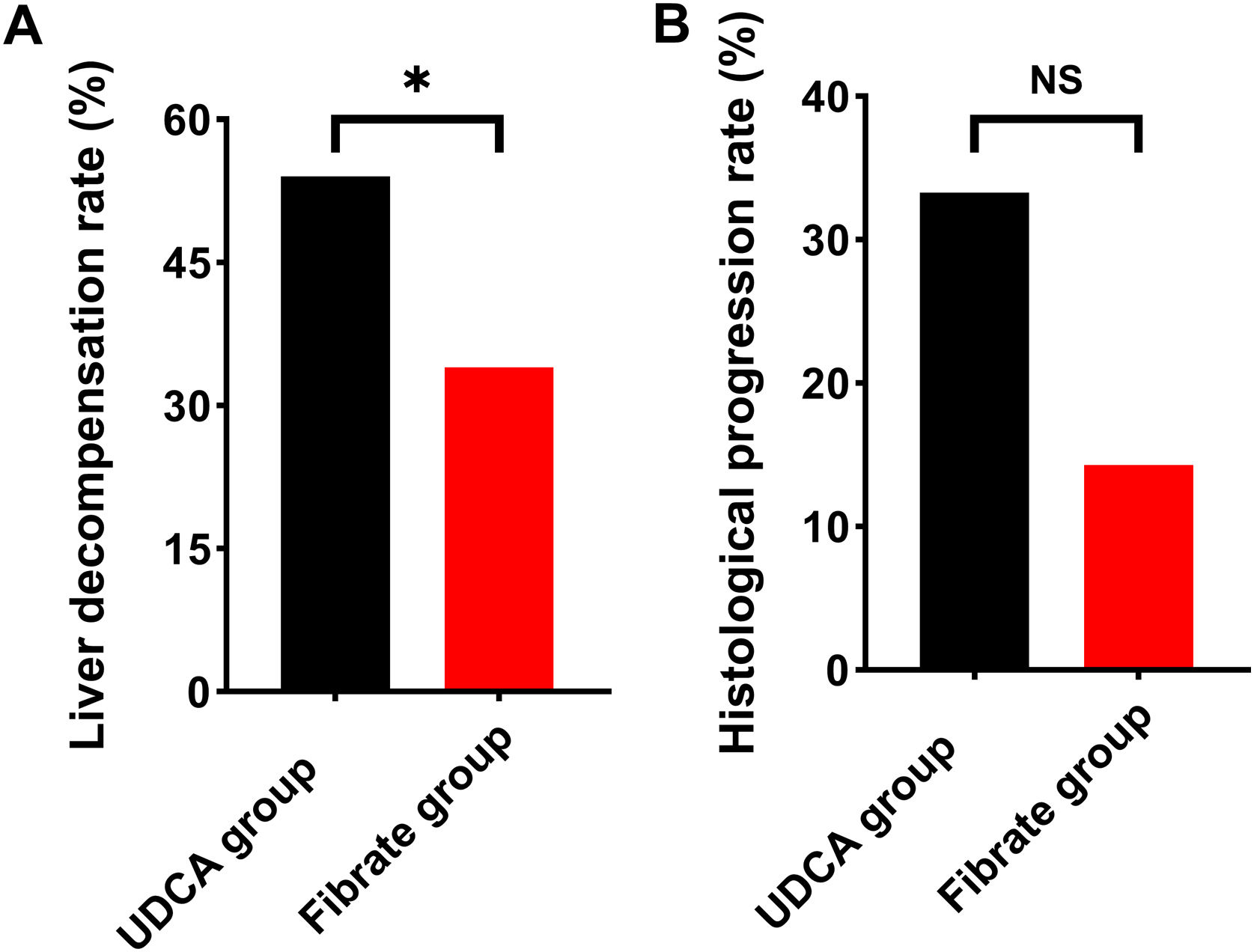

Liver decompensation and histological progressionDuring follow-up, liver decompensation occurred in 22 (34%) fenofibrate-treated participants and 29 (54%) UDCA-treated participants at a median of 36 months (range 9–102 months) and 33 months (range 8–72 months), respectively. The fenofibrate-treated participants had a significantly lower rate of liver decompensation when compared to the UDCA-treated participants (P=0.053; Fig. 3A). Supplementary Table 1 depicted the composition of liver decompensated events. During treatment, 27 (42%) fenofibrate-treated participants and 12 (22%) UDCA-treated participants had a minimum of two liver biopsies at median intervals of 30 months (range, 12–84 months) and 33 months (range, 12–84 months), respectively. There was no significant difference in histological progression between the two groups (Fig. 3B).

The incidence of liver decompensation and histological progression between the Fibrate group and the UDCA group. (A) Liver decompensation rate. (B) Histological progression rate. Data was analyzed by the chi-squared test (*P<0.05; NS, no significance).

UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; Fibrate, fenofibrate.

Supplementary Fig. 2 demonstrated the specific improvements in median UK-PBC and Globe scores during therapy. At 60 months, the UK-PBC and Globe scores were identified to be 32% and 41% lower than after 12 months of fenofibrate treatment, respectively, but 19% and 20% higher in the UDCA-treated participants. Globe scores greater than 0.30 have previously been shown to predict significantly lower LT-free survival time when compared to a matched healthy population.16 At baseline, 56 (88%) fenofibrate-treated participants and 51 (94%) UDCA-treated participants had a Globe score greater than 0.30 (P=0.362). After 12 months of fenofibrate therapy, 43 (67%) fenofibrate-treated participants, and 50 (92%) UDCA-treated participants had a Globe score of >0.30 (P=0.001). Significant improvements in the median UK-PBC and Globe scores were observed in fenofibrate-treated participants when compared to those that were treated with UDCA.

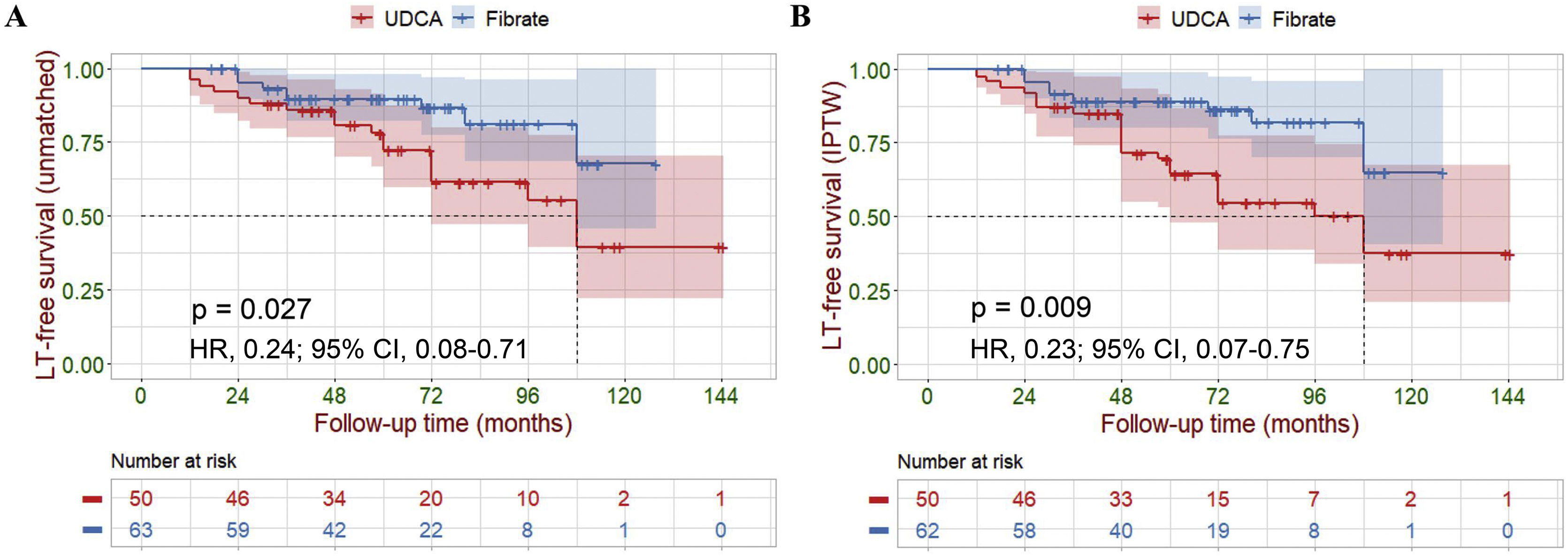

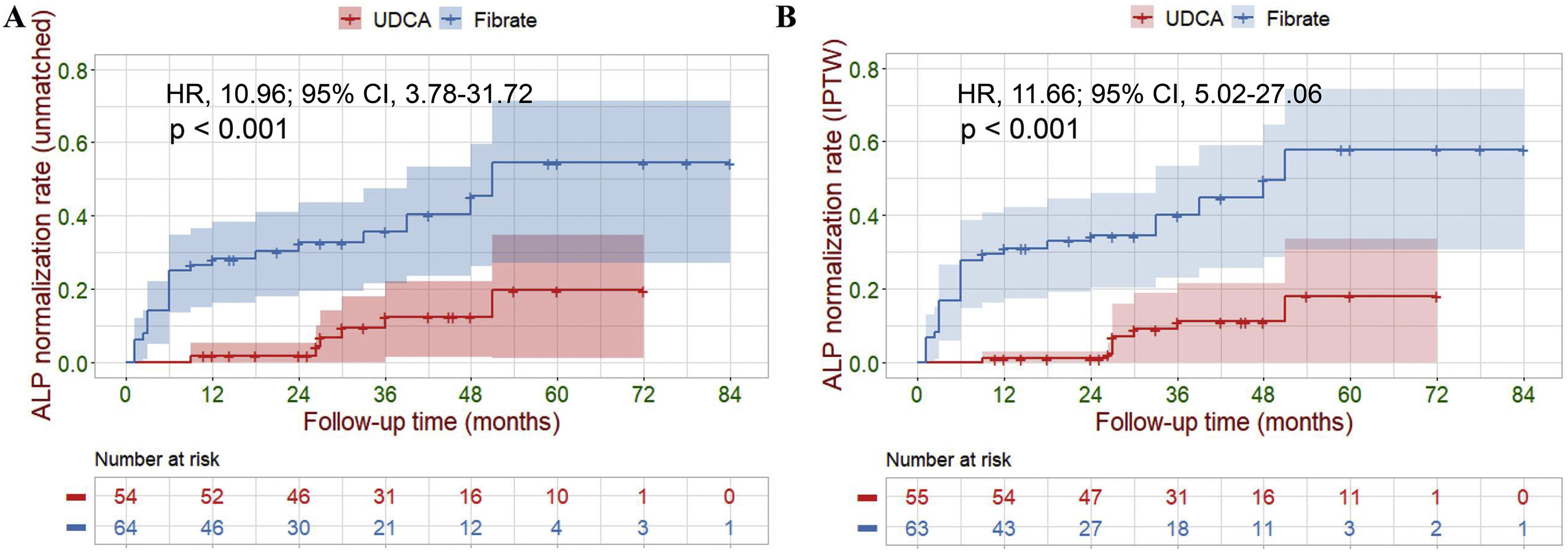

Primary outcomesFive participants were lost to final follow-up; their survival data were not available for analysis. Of the 113 (96%) remaining participants, LT and liver-related deaths occurred in 1 (2%) and 8 (12%) of the fenofibrate-treated participants compared to 1 (2%) and 17 (34%) of the UDCA-treated participants (14% vs. 36%, P=0.007). Cox analyses demonstrated a highly significant reduction in the hazard ratio of liver-related death or LT attributable to fenofibrate therapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08–0.71; P=0.010). Log-rank analyses demonstrated a similar result (P=0.027, Fig. 4A). During treatment, six UDCA-treated participants, and twenty-four fenofibrate-treated participants achieved ALP normalization (11% vs. 37%, P=0.001). Cox analyses demonstrated a highly significant increase in the hazard ratio for ALP normalization (HR, 10.96; 95% CI, 3.78–31.72; P<0.001). Log-rank analyses demonstrated a similar result (P<0.001, Fig. 5A). To further estimate the efficacy of fenofibrate therapy, we used logistic regression analysis to calculate propensity scores using retrospective data. We also performed KM survival analysis, and Cox regression analysis, after IPTW adjustment for a baseline differential indicator (GGT) and potential prognostic relevant indicators (e.g., gender, age, prior UDCA therapy, ALP, Tbil, ALT, AST, ALB and PLT). After weighting, all covariates achieved P>0.05 and a standardized mean difference <0.1, achieving group balance (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Weight-adjusted Cox analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in the hazard ratio of liver-related death or LT attributable to fenofibrate therapy (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.75; P=0.015). Weight-adjusted log-rank analyses demonstrated similar result (P=0.009, Fig. 4B). Weight-adjusted Cox analyses demonstrated a significant increase in the hazard ratio for ALP normalization (HR, 11.66; 95% CI, 5.02–27.06; P<0.001). Weight-adjusted log-rank analyses demonstrated similar result (P<0.001, Fig. 5B).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of LT-free survival between the UDCA group and the Fibrate group. (A) Before IPTW (unmatched). (B) After IPTW. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval. Survival curves were compared with the log-rank test.

LT, liver transplantation; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighing; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; Fibrate, fenofibrate; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of ALP normalization rate between the UDCA group and the Fibrate group. (A) Before IPTW (unmatched). (B) After IPTW. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence interval. Survival curves were compared with the log-rank test.

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighing; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; Fibrate, fenofibrate; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

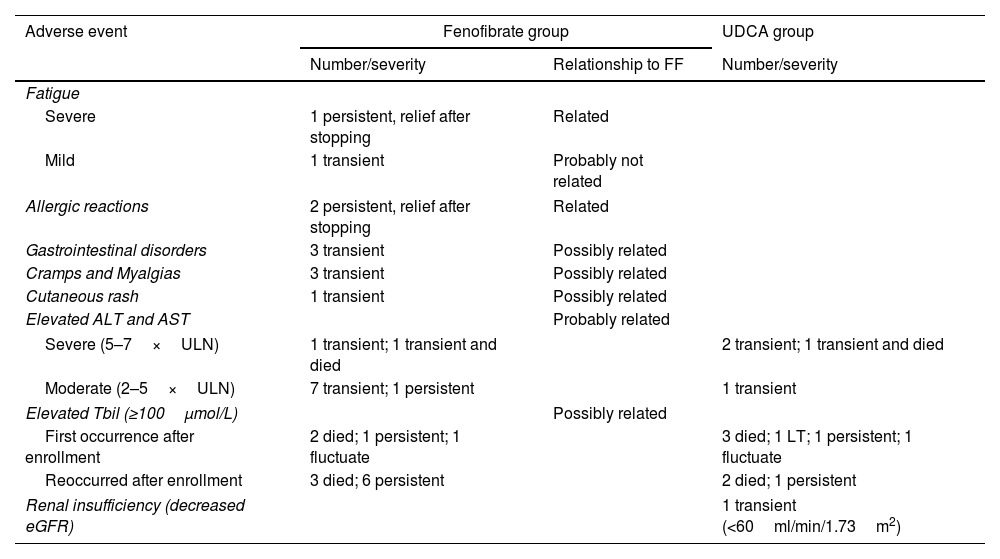

As shown in Table 2, the most frequent AEs were gastrointestinal symptoms, cramps and myalgia, and aminotransferase elevations. Two (3%) participants experienced severe allergic reactions during the first two months, and one (2%) participant experienced worsened fatigue at 24 months; these AEs were resolved after fenofibrate was removed. Severe elevations in transaminase levels were detected in two (3%) participants after 12 and 24 months of fenofibrate therapy, respectively; these progressively declined, even after continued fenofibrate therapy with monthly surveillance in both participants; one of the two participants died a year later from malnutrition due to liver decompensation, which was unrelated to fenofibrate. After enrollment, five (9%) UDCA-treated participants, and four (6%) fenofibrate-treated participants developed severe deteriorations in Tbil levels.

Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Fenofibrate group | UDCA group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number/severity | Relationship to FF | Number/severity | |

| Fatigue | |||

| Severe | 1 persistent, relief after stopping | Related | |

| Mild | 1 transient | Probably not related | |

| Allergic reactions | 2 persistent, relief after stopping | Related | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 3 transient | Possibly related | |

| Cramps and Myalgias | 3 transient | Possibly related | |

| Cutaneous rash | 1 transient | Possibly related | |

| Elevated ALT and AST | Probably related | ||

| Severe (5–7×ULN) | 1 transient; 1 transient and died | 2 transient; 1 transient and died | |

| Moderate (2–5×ULN) | 7 transient; 1 persistent | 1 transient | |

| Elevated Tbil (≥100μmol/L) | Possibly related | ||

| First occurrence after enrollment | 2 died; 1 persistent; 1 fluctuate | 3 died; 1 LT; 1 persistent; 1 fluctuate | |

| Reoccurred after enrollment | 3 died; 6 persistent | 2 died; 1 persistent | |

| Renal insufficiency (decreased eGFR) | 1 transient (<60ml/min/1.73m2) | ||

Supplementary Fig. 4 demonstrates the specific changes in parameters relating to renal function. Although there was a slight trend toward eGFR deterioration in UDCA-treated participants, the median eGFR and serum creatinine (Scr) had stabilized in both groups by the end of the study. The median Scr levels and eGFR did not differ significantly between the two groups. One UDCA-treated participant experienced transient kidney deterioration.

DiscussionOur study identified that in patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC, additional fenofibrate therapy resulted in a significant improvement in LT-free survival and ALP normalization. Similar improvements were observed in terms of liver decompensation and histological progression. During follow-up, we did not observe any severe fenofibrate-related AEs. In view of this, additional fenofibrate therapy appears to be a suitable alternative option for this population of patients.

Published studies have shown that fenofibrate improved biochemical markers and LT-free survival in patients with UDCA-refractory PBC,12,13,26–28 but data evaluating efficacy of fenofibrate add-on therapy were limited in advanced patients. In the current study, Cox regression analyses and Log-rank test demonstrated that fenofibrate-treated participants reported improved LT-free survival and ALP normalization when compared to those receiving UDCA monotherapy. There was also a significant decrease in the occurrence of liver decompensated events. We also noticed a slight improvement in histological progression. However, only 39 patients had at least two liver biopsies with a relatively short mean intervals (31 months), which is insufficient to assess improvement in liver fibrosis. These biopsies provided us important information of disease progression and treatment responses, and more biopsies might be considered in other patients to generate more reliable clinical evidence for managing such patients.

These specific improvements in fenofibrate-treated participants were accompanied by a rapid and consistent reduction in ALP level and a relatively stable Tbil level during follow-up; these are the two most important prognostic indicators in patients with PBC.3 Similar improvements were observed in ALB and PLT levels compared to UDCA-treated participants. The recurrence of ALP levels after the withdrawal of fenofibrate, and the progressive reduction of ALP levels after resuming fenofibrate therapy, clearly demonstrated the beneficial effects of fenofibrate.

The UK-PBC and Globe risk scores are disease-specific models that have been validated in Asian patients to predict prognosis, and they appear to have some advantages over the use of individual hematological findings alone and the traditional binary UDCA response criterion.29 Using these novel risk assessment tools, we found that add-on fenofibrate therapy to patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC significantly improved the predicted incidence of LT-free survival when compared with UDCA-treated participants. Furthermore, despite observing a stabilization effect, add-on fenofibrate therapy failed to demonstrate any significant improvements in the UK-PBC and Globe risk scores in advanced patients by the end of the study.

A major target of our study was to determine the security of fenofibrate therapy in advanced and UDCA-refractory PBC patients. It is noteworthy that Cheung et al.12 demonstrated that exposure to fenofibrate was associated with an increased acceleration of serum bilirubin levels in advanced PBC and recommended its use in cirrhotic patients with caution. In contrast, our current study demonstrated that the median levels of serum Tbil remained stable in fenofibrate-treated participants over 60 months of follow-up; no significant differences were found when compared to UDCA-treated participants. Indeed, four fenofibrate-treated participants experienced deterioration in Tbil levels after relatively long periods of fenofibrate therapy, indicating that the deterioration appeared to be associated with disease progression rather than fenofibrate therapy; there was no significant difference in the rate of Tbil deterioration between the two groups.

Fenofibrate-related nephrotoxicity is still debated, with several authors reporting contradictory findings.9,14,26–28 Notably, deterioration in both eGFR and Scr was previously demonstrated in patients with UDCA-refractory PBC after add-on fenofibrate therapy.14 In our study, there were no significant deteriorations in Scr or eGFR, even after up to 60 months of fenofibrate therapy in advanced participants when compared to the UDCA-treated. In addition, two participants with severe transaminases elevations, and eight participants with moderate transaminases elevations experienced potential hepatotoxicity, which was presumably due to the activation of transaminase gene expression by PPAR-a.30,31 The levels of transaminases declined gradually, even after discontinuing fenofibrate therapy during subsequent follow-up visits.

Our single-center design and relatively small sample size restricted the capacity for generalization of these results. It is possible that there were some confounding parameters remaining in our analyses that could not be excluded. Therefore, caution is required in the interpretation of these results. We also acknowledge that only a minority of patients completed 60 months of treatment. Furthermore, only a small number of patients undergo at least two liver biopsies, the effect of fenofibrate on histological progression remains unanswered.

In conclusion, significant improvements in LT-free survival and the rate of ALP normalization when compared to UDCA monotherapy demonstrated that supplementary fenofibrate therapy was clinically beneficial in patients with advanced and UDCA-refractory patients with PBC. Furthermore, this combined therapy appeared to be safe and well tolerated. Consequently, supplementary fibrate therapy appears to be a safe and efficacious alternative for patients with advanced UDCA-refractory disease. Further research, using a larger prospective cohort, now needs to confirm these findings.

FundingThe study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81820108005, 81900502, and 82173241), National Key Research and Development (R&D) Program of China (No. 2017YFA0105704) and Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (No. 2021ZDLSF02-07).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests related to this publication.

Authors’ contributionsStudy design (YH, YLS, XMZ), acquisition of data (DWD, PWR), analysis and interpretation of data (GYG, CMY, GJ, CCG), statistical analysis (JD, LHZ, XFW, RQS), and manuscript writing (DWD, YSL).

We thank the entire medical staff of the Gastroenterology Department for their support of the study.