To determine if anxiety and depression are associated with a lower QoL in patients with UC in remission.

Patients and methodsWe included consecutive patients with a previously confirmed diagnosis of UC in remission for at least 12 months and who answered complete questionnaires: IBDQ-32, HAD. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics were obtained. We performed non-parametric tests, and correlations between HADS and IBDQ-32 were analyzed using Spearman's correlation coefficient (r). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

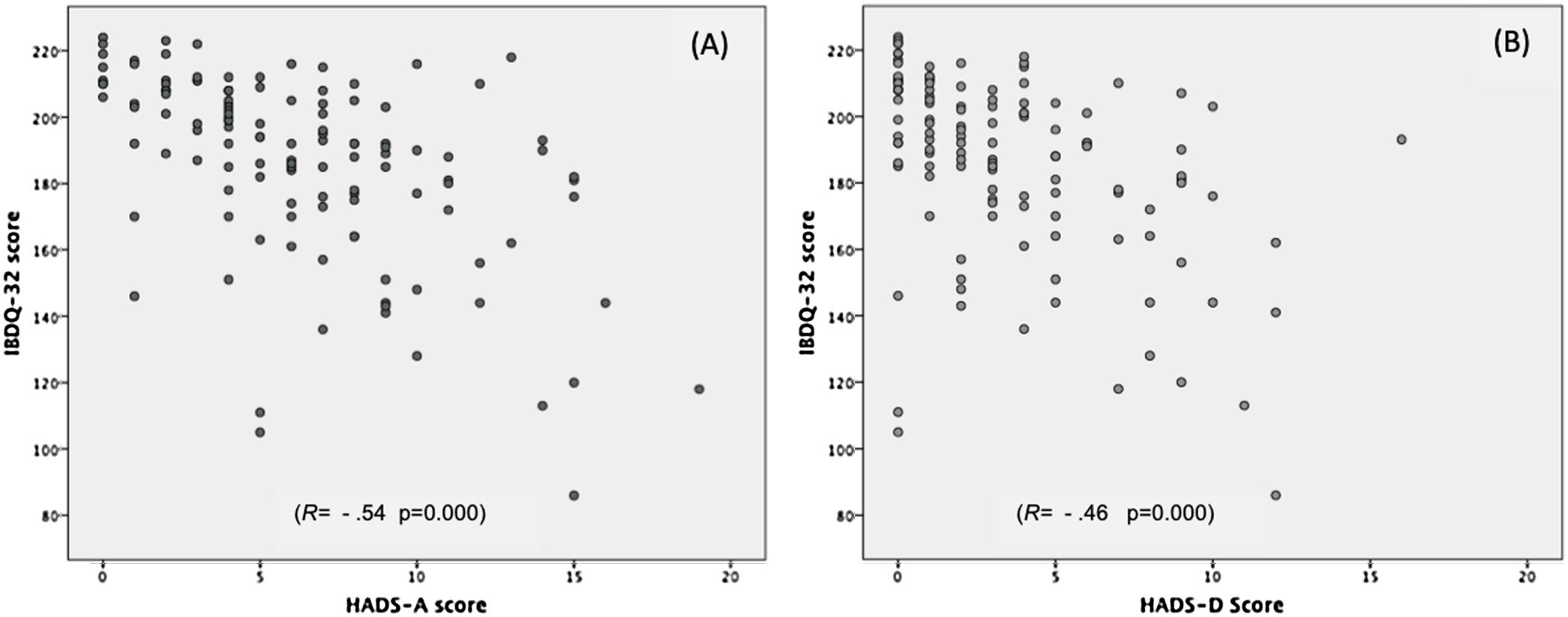

ResultsAmong 124 patients, 65% were men, with a median evolution of UC of 10 years (IQR: 5–79 years). Prevalence for anxiety was 15.3% and 2.4% for depression. Global QoL was 192 (IQR: 175–208). Lower QoL was associated with anxiety (p=0.002) and depression (p=0.013). Depression represented lower QoL at the digestive level than no depression (p=0.04). Anxiety negatively correlated with QoL (r=−0.54; p<0.001).

ConclusionsAnxiety is frequent in patients with UC in remission; therefore, timely diagnosis and treatment must be implemented to improve QoL.

Determinar si la ansiedad o depresión están asociados con pobre calidad de vida en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa en remisión.

Pacientes y métodosSe incluyó a pacientes de manera consecutiva con diagnóstico establecido de colitis ulcerosa en remisión de al menos 12 meses y quienes completaron los cuestionarios de manera completa como el IBDQ-32, HAD. Las características sociodemográficas y clínicas fueron recabadas. Se utilizaron pruebas no paramétricas y se realizó correlación de HADS y IBDQ-32 con la prueba de Spearman (r). Un valor de p < 0,05 fue considerado como significativo.

ResultadosDe los 124 pacientes, el 65% fueron hombres con una media de 10 años de evolución (IQR: 5-79 años). La prevalencia para la ansiedad fue del 15,3% y el 2,4% para depresión. La calidad de vida global fue de 192 puntos (IQR: 175-208). La pobre calidad de vida estuvo asociada con la ansiedad (p = 0,002) y la depresión (p = 0,013). La depresión estuvo representada como pobre calidad de vida a nivel de las esferas digestiva (p = 0,04). La ansiedad se correlacionó de manera negativa con la calidad de vida (r = –0,54; p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLa ansiedad es frecuente en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa en remisión; no obstante, el diagnóstico y el tratamiento oportuno debe ser implementado para mejorar la calidad de vida.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a lifelong, chronic, incurable disease characterized by an intermittent relapsing–remitting clinical course.1 Clinical manifestations include chronic diarrhea, which may present with mucus or blood, straining and rectal tenesmus, nocturnal bowel movements, weight loss, fever, and abdominal pain.2 Nonetheless, UC manifestations are not limited to the colon itself. At least 1 in 4 patients develops extraintestinal manifestations.3,4 UC has been a frequent disease in industrialized countries, but its incidence has recently increased in countries around Asia and Latin America, including Mexico.5

Quality of Life (QoL) is defined as an individual's perception of their place in existence in the context of culture, the value system in which they live regarding their objectives, normal expectations, and concerns. The concept is influenced by physical, psychological, and emotional health, as much as the level of independence and social relations.

In a meta-analysis study, Knowles et al.6 stated that UC patients have lower QoL than healthy people, indistinctly in adults and younger populations. Also, the patients showed a slight increase in QoL compared to other chronic gastrointestinal conditions such as Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder (FGID).

A lower QoL in UC patients has been associated with different factors, with the relapse period as the most relevant. To date, the level of QoL cannot be solely explained by the intensity of UC symptoms.7

Therefore, special attention should be given to psychosocial variables such as depression and anxiety as they negatively affect the QoL during the remission phase of the disease, which is why the identification of other variables that are associated with a lower QoL during remission would rely upon the proper enforcement of identification strategies for timely diagnosis and treatment, all of which could lead to an improvement in the QoL and functioning of these patients.

We aim to establish whether the presence of anxiety and depression is associated with a lower QoL in patients with UC in remission and to estimate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in this population.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a prospective analysis of 124 patients who attended outpatient checkups at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (INCMNSZ) from March 2018 to November 2019. The included patients were ≥18 years of age, had a confirmed diagnosis of UC (based on conventional clinical, endoscopic, radiographic, and histological criteria), and had more than 2 years of disease evolution. Patients were excluded if they were unable to adequately complete the questionnaires due to cognitive impairment or unwillingness to participate in the study. Sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data were obtained from the physical and electronic medical records. All patients signed an informed consent form for their participation in the study. The Investigation and ethics board approved the study at the INCMNSZ, and research was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (REF 2680).

We required a remission period of at least 12 months. Remission was defined at the time of clinical evaluation, with a pMayo Score of 0–1 point, plus fecal calprotectin (FC)<50μg/mg, and inflammatory markers (hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, sedimentation rate, and albumin) within normal parameters. Patients were not required to add or change any medication at the time of the clinical evaluation or during the previous 12 months. The clinical records of each patient were reviewed to verify clinical remission. We used the partial Mayo Score because it is a commonly used index to assess the severity of UC and its clinical response to treatment as perceived by the patients. It evaluates stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and the physician's global assessment.8 The score ranges from 0 to 9, where higher scores indicate more severe disease. CF has become one of the most useful and frequently used tools for caring for patients with IBD. A correlation between CF levels and the healing of the colonic mucosa and its histology has been identified in patients with IBD.9

Quality of life evaluationQuality of life was analyzed with the 32-items version of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ-32). It evaluates QoL by using 32 items divided into 4 domains, including intestinal symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional functioning, and social functioning. Responses are scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=a severe problem; 7=not a problem). Dimensional scores are the sum of the scores obtained in each dimension. The total QoL score is the sum of the scores of the 4 domains, ranging from 32 to 224 points, where higher scores indicate a better QoL. The IBDQ-32 is the most frequently used tool to evaluate QoL,10 it has adequate validity and reliability and has been validated in Mexico.

To determine the presence of anxiety and depression, we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which has already been validated in patients with IBD in Mexico.11 This self-applied scale of 14 items includes 7 items for the anxiety sub-scale (HAD-A) and 7 for the depression sub-scale (HAD-D). Likert response options range from 0 to 3 points. The presence of anxiety and depression was defined by a score of ≥11 on its respective subscale.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed where continuous variables were evaluated with non-parametric tests. Chi-square or Fisher's exact was used to compare categorical variables, Mann–Whitney's U test was used for quantitative variables, and Pearson correlation coefficient (R) was used for correlation. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software v21.

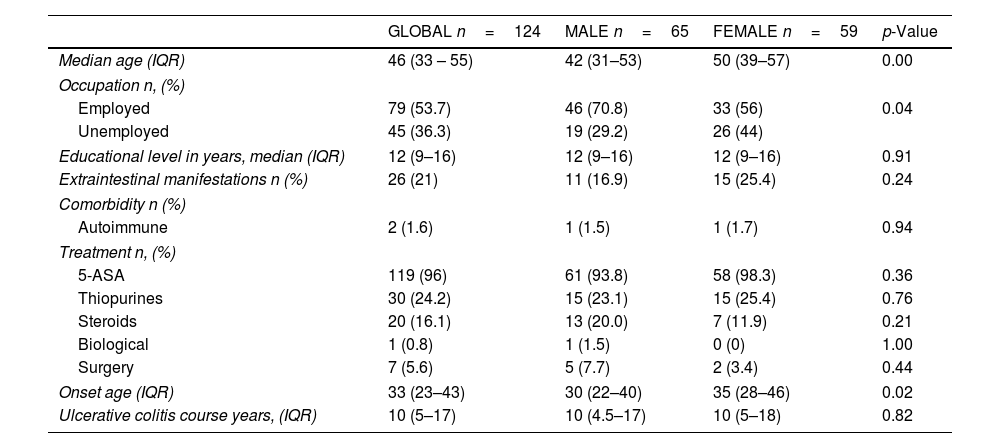

ResultsGeneral characteristicsAmong 124 patients evaluated, 52.4% were men, median age of 46 years (IQR: 33–55). Men were younger at the time of the study. The main clinical and sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of inactive ulcerative colitis patients and differences based on gender.

| GLOBAL n=124 | MALE n=65 | FEMALE n=59 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 46 (33 – 55) | 42 (31–53) | 50 (39–57) | 0.00 |

| Occupation n, (%) | ||||

| Employed | 79 (53.7) | 46 (70.8) | 33 (56) | 0.04 |

| Unemployed | 45 (36.3) | 19 (29.2) | 26 (44) | |

| Educational level in years, median (IQR) | 12 (9–16) | 12 (9–16) | 12 (9–16) | 0.91 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations n (%) | 26 (21) | 11 (16.9) | 15 (25.4) | 0.24 |

| Comorbidity n (%) | ||||

| Autoimmune | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.7) | 0.94 |

| Treatment n, (%) | ||||

| 5-ASA | 119 (96) | 61 (93.8) | 58 (98.3) | 0.36 |

| Thiopurines | 30 (24.2) | 15 (23.1) | 15 (25.4) | 0.76 |

| Steroids | 20 (16.1) | 13 (20.0) | 7 (11.9) | 0.21 |

| Biological | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Surgery | 7 (5.6) | 5 (7.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.44 |

| Onset age (IQR) | 33 (23–43) | 30 (22–40) | 35 (28–46) | 0.02 |

| Ulcerative colitis course years, (IQR) | 10 (5–17) | 10 (4.5–17) | 10 (5–18) | 0.82 |

IQR, interquartile range.

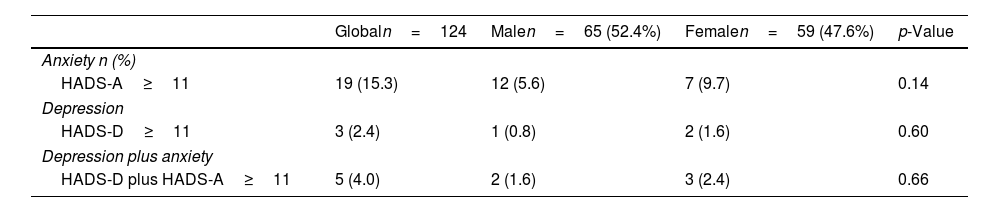

For the total population, 19 patients presented anxiety (15.3%), 3 depression (2.4%); and 5 cases (4.0%) had both conditions, as seen in Table 2. No differences were seen in the prevalence of anxiety and depression by gender and treatment type.

Prevalence of anxiety and depression and differences base on gender.

| Globaln=124 | Malen=65 (52.4%) | Femalen=59 (47.6%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety n (%) | ||||

| HADS-A≥11 | 19 (15.3) | 12 (5.6) | 7 (9.7) | 0.14 |

| Depression | ||||

| HADS-D≥11 | 3 (2.4) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0.60 |

| Depression plus anxiety | ||||

| HADS-D plus HADS-A≥11 | 5 (4.0) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.4) | 0.66 |

HADS: hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS-D: depression sub-score; HADS-A: anxiety sub-score.

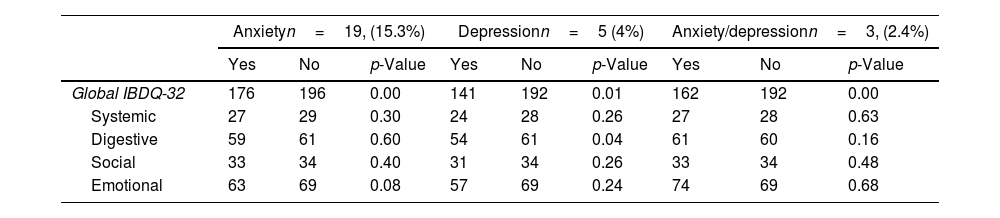

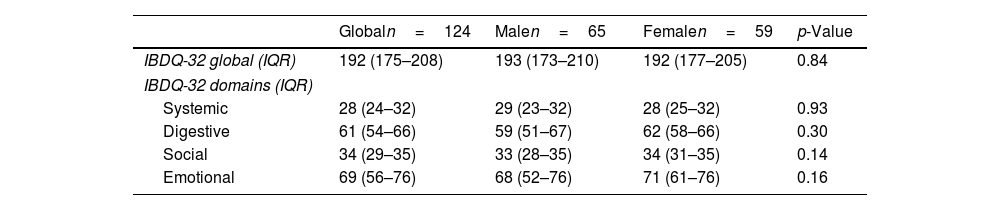

Globally, the QoL score was 192 (IQR: 175–208). For each of the domains evaluated by the IBDQ-32, each one scored: systemic 28 (IQR: 24–32); digestive: 61 (IRQ: 54–66); social: 34 (IQR: 29–35) and emotional: 69 (IQR: 56–76). No differences were identified in the global score of IBDQ-32 and each of the domains when compared to women and men. Table 3 shows the results of the QoL obtained through the IBDQ-32 questionnaire. No differences were identified in the global score of IBDQ-32 when comparing patients with extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) vs. no EIMs and steroids prescription vs. no steroid prescription, respectively (p=0.162); (p=0.742). The QoL in patients with anxiety was 176 vs. 196 (p=0.002), depression was 141 vs. 192 (p=0.01), and both conditions 162 vs. 192 (p=0.003), being significantly lower compared to those patients without psychiatric comorbidity. The analysis of the IBDQ-32 showed that patients with depression presented significantly lower QoL in the digestive domain compared to those without depression (54 vs. 61 points, p=0.04); no differences were identified in the rest of the dimensions, as seen in Table 4.

Global and domains of quality of life, and differences based on gender.

| Anxietyn=19, (15.3%) | Depressionn=5 (4%) | Anxiety/depressionn=3, (2.4%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p-Value | Yes | No | p-Value | Yes | No | p-Value | |

| Global IBDQ-32 | 176 | 196 | 0.00 | 141 | 192 | 0.01 | 162 | 192 | 0.00 |

| Systemic | 27 | 29 | 0.30 | 24 | 28 | 0.26 | 27 | 28 | 0.63 |

| Digestive | 59 | 61 | 0.60 | 54 | 61 | 0.04 | 61 | 60 | 0.16 |

| Social | 33 | 34 | 0.40 | 31 | 34 | 0.26 | 33 | 34 | 0.48 |

| Emotional | 63 | 69 | 0.08 | 57 | 69 | 0.24 | 74 | 69 | 0.68 |

IBDQ32: inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire 32 items.

Association of anxiety (HADS-A≥11) and depression (HADS-D≥11) with quality of life.

| Globaln=124 | Malen=65 | Femalen=59 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBDQ-32 global (IQR) | 192 (175–208) | 193 (173–210) | 192 (177–205) | 0.84 |

| IBDQ-32 domains (IQR) | ||||

| Systemic | 28 (24–32) | 29 (23–32) | 28 (25–32) | 0.93 |

| Digestive | 61 (54–66) | 59 (51–67) | 62 (58–66) | 0.30 |

| Social | 34 (29–35) | 33 (28–35) | 34 (31–35) | 0.14 |

| Emotional | 69 (56–76) | 68 (52–76) | 71 (61–76) | 0.16 |

HADS: hospital anxiety depression scale; IBDQ-32: inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire 32 items; HADS-D: hospital anxiety depression scale depression sub-score; HADS-A: hospital anxiety depression scale anxiety sub-score.

The anxiety score (HADS-A), depression (HADS-D), and total HADS were negatively correlated with the QoL level (r=−0.54, p<0.001) (r=−0.46, p<0.001) and (r=−0.54, p<0.001) respectively (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates an interrelation of anxiety and depression with a decline in the QoL among UC patients, independent of other variables associated with the deterioration in QoL, such as sex, age, years of evolution of the disease, type of pharmacological treatment or a history of surgical treatment. It also confirms a high prevalence of anxiety in UC patients even after clinical remission of at least 12 months.

To our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in Latin America that analyzes this interaction in a geographical region with an increasing incidence of IBD. Assessing the QoL of UC patients during remission is relevant for the social functioning and mental health issues of these patients. Several studies have identified relapse as the main factor associated with deterioration in the patient, but even in patients without a relapse, we could also report mental health issues. Other reported mental disorders to be aware are mood disorders, anxiety, self-harm, suicide, and sleep disorders in this population.12,13 Nonetheless, scarce data is available on the impact of these disorders on patients during the remission period.

Medical literature has reported a prevalence of depression of 2 to 16.5%14–17 in patients with IBD in the remission phase. And this variability could be explained due to different criteria used by the authors to define depression and anxiety, the type of instrument, and the cuff-off point used. In the case of the scale that is being used [HADS 17.6% (95% CI 14.8–20.4), p=0.003 vs. Beck Depression Inventory 33% (95% CI 21.6–44.4); p<0.001] and for the cut-off point used to define the presence of depression, HADS-D with a cut-off point >7, reveals an average prevalence of 18.7% [95% CI 15.6–22.0] and for HADS-D with a cut-off point >10 shows an average prevalence of 11.8% [95% CI 6.8–16.9].18 In this study, we report a prevalence of depression of 2.4%, as shown in several studies,14–16,19 and we could explain this due to the questionnaire and the cut-off point used and also due to the stage of the disease of our patients.

Anxiety can range from 7.8% to 57%,14–17 and when measured through HADS-A, it is 33% [95% CI 28.6–37.9], but it can also vary depending on the established cut-off point. By using HADS-A >7, the average reported prevalence is 39.4% [95% CI 34.3–44.4], while a cut-off point of HADS-A >10 reported an average prevalence of 20.7% [95% CI 12.5–28.9].26 In our study, we found a prevalence of 15.3%, which is even higher than the anxiety prevalence for the general Mexican population.20 Comparatively, similar results were reported by Kim et al.,21 in a study that included 119 patients with UC in remission, with an average age of 45.8±16.7 years, showing a prevalence of anxiety (HADS-A>7) was 24.4% and depression (HADS-D>7) of 27.7%. Compared to our population, both results were higher, probably due to the cut-off point of HADS used by the authors.

In the case of patients with anxiety and depression, our prevalence was 4%. We believe this could be attributed to the cut-off point that let us adequately identify this set of patients. Furthermore, this study shows that patients with anxiety and depression would have a lower QoL even in an inactive phase of the disease. Bryant et al.22 reported 63 patients (38.8%) with the diagnosis of UC (32 in remission), with a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression (HADS>7) in patients who had any FGID compared to those who didn’t (anxiety: 78% vs. 22% and depression 89% vs. 11%, p<0.001). They also identified a negative interrelation between depression and anxiety (r=−0.43, r=−0.54 p<0.001), similar to the one found in our study. In this scenario, QoL levels were adjusted for age, sex, type of IBD, disease activity, and presence and type of FGID.

Among the factors associated with a low QoL defined by a<8 score on Euro Quality of Life (EQ-5D) were: the presence of functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (both p<0.01), anxiety (p<0.01) and depression (p<0.01). The multivariate analysis was adjusted for age, place of residence, and FGID. Associated factors linked to a low QoL were age≥40 years [OR 2.34 (95% CI 1.19–4.59)], Irritable Bowel Syndrome [OR 3.93 (95% CI 1.93–7.98)] and anxiety [OR 2.42 (95% CI 1.06–5.50)]. In a study including 44 UC patients in remission (36%) with a reported prevalence for depression (HADS-D>10) of 13.6% and anxiety (HADS-A>10) of 20.5%. Anxiety, religion, age over 40 years, and smoking were identified as predictors of a lower QoL (p<0.001; r2=0.60).15

Regarding depression, Zhang C et al.,23 in a cohort study with 16 patients in remission, showed a prevalence of depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II) of 10.3%, being the main predictor for a low QoL (p<0.001). Casellas F et al.24 found that from 160 patients with UC, 107 patients in remission had low QoL at the systemic level compared to the intestinal, social, emotional, and functional domains (p<0.001). Anxiety and depression were not analyzed.

Iglesias-Rey M.25 studied the effect of different sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables on the QoL. High levels of anxiety and depression were found to be associated with low levels in all QoL measurements. In contrast, our study identified that depression was associated with lower QoL OR: 2.98 (95% IC 1.72–5.15) but not anxiety.

In contrast, our study identified that patients with depression had a lower QoL at the digestive level compared to those without depression. The Autonomous Nervous System probably mediates the response that stress, depression, and anxiety have on UC, and the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis, both signaling circuits, are part of the so-called brain-gut-microbiota axis, which communicates the gastrointestinal tract with the Central Nervous System, favoring intestinal permeability, bacterial translocation, and low-grade inflammatory activity.17,26 Recently Melina-Iordache et al.27 identified a moderate, positive correlation between depression score and calprotectin (rs(30)=0.416, p=0.022 and a weak, negative correlation between depression score and QoL (r (30)=−0.372, p=0.043). Anxiety and mood disorders have been associated with intestinal dysbiosis and the growth of molecules of intestinal epithelial integrity in the blood of asymptomatic subjects with gastrointestinal physical suffering.

As referenced before, other factors associated with lower QoL are female gender, low educational level, age over 40 years, inadequate social support, high level of stress living in one province, and less knowledge about their disease.28 We found no association with these data in our study.

Therefore, it is important to consider the comorbidity of anxiety and depression in patients with UC in remission, as it can have different clinical implications. First, the QoL of these patients decreases, regardless of disease activity. Second, the presence of this comorbidity can have a negative impact on the clinical course of UC, as mentioned before, due to its interrelation to the relapse of the disease,29 greater substance use30 and less therapeutic adherence.31 In addition, a lower QoL has been associated with less functioning and a greater number of medical visits at the first level of care. Thus, timely identification and proper treatment of these patients can improve their prognosis.

We present a study with plentiful strong points. Our cohort includes patients with clinical remission over 12 months, confirmed through clinical evaluation and the use of inflammatory markers, both systemic and specific for intestinal inflammation, such as CF. In addition, we use HADS, a widely used instrument validated in our population, using a cut-off point with higher diagnostic features. Finally, to assess QoL, we used the IBDQ-32 questionnaire, a specific instrument for patients with IBD that, in addition to being the most widely used, has adequate reliability and validity.

We are also aware of the limitations, being that it is a cross-sectional study, and a causal relationship cannot be established between affective symptoms and QoL. Besides, factors such as FGID were not considered.

In conclusion, this study shows that the presence of anxiety is high during the inactivity phase of the disease, and its presence and severity can negatively impact the QoL of these patients. Considering the increase in the incidence of IBD in our geographic region, special attention should be given to QoL and its associated factors since proper management of anxiety and depression have the potential to improve not only QoL but the course of the disease, making mental health care a fundamental element of comprehensive care in UC patients, regardless of the clinical stage in which they are.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Conflict of interestThe authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

None.