Casos Clínicos en Gastroenterología y Hepatología

Más datosWilson's disease (WD) is a rare genetic disorder resulting from a mutation in the ATP7B gene on chromosome 131 that results in the accumulation of copper. The onset of symptoms can be at any age and the main features are liver disease, neuropsychiatric disturbances, Kayser–Fleischer rings and acute hemolytic episodes.1,2

Diagnosing WD is not easy, and a high index of suspicion is needed. Furthermore, its co-existence with other frequent liver diseases like metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) can make diagnosis even more challenging. In this report, we describe a patient with MAFLD who was diagnosed with WD after presenting with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia.

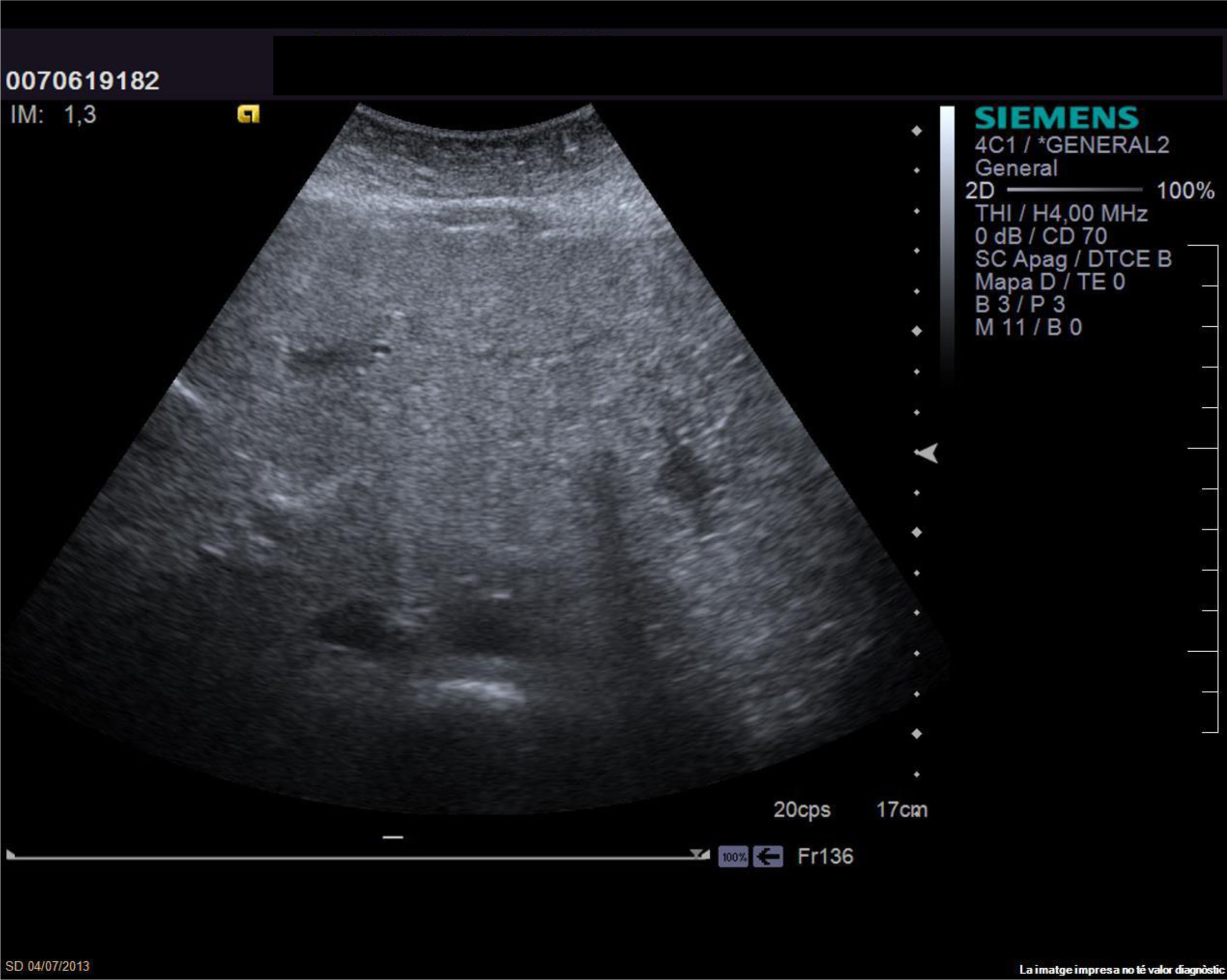

Case reportA 59-year-old woman was admitted for marked derangement of liver function in September 2019. In 2002, MAFLD had been diagnosed after altered liver tests in the setting of arterial hypertension and class II obesity (body mass index 38) with steatosis at ultrasound. In 2013, a liver biopsy confirmed steatohepatitis and cirrhosis (Fig. 1). Personal history included depressive syndrome and there was no family history of chronic liver disease.

She remained compensated until 2019, when she was admitted for encephalopathy and jaundice (Table 1). Ultrasound discarded malignancy and portal vein thrombosis and a liver biopsy showed steatohepatitis with cirrhosis. Acute viral hepatitis was also discarded. Blood tests were remarkable for Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, in the investigation of which 24h urine copper resulted 1256μg/24h (NR<40μg/24h). Blood ceruloplasmin level was 0.14g/l (NR 0.17–0.37g/l), and there were no Kayser-Fleischer rings or neurological symptoms. Following the Leipzig criteria (4 points), a WD clinical diagnosis was made.

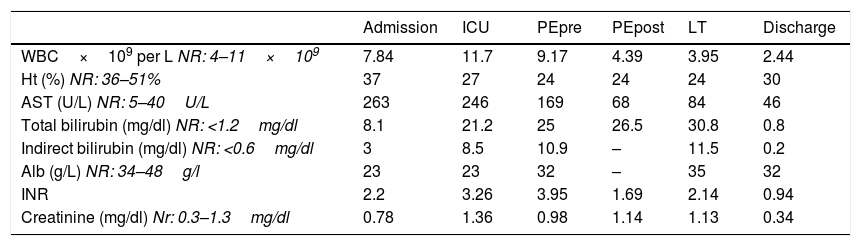

Biochemical and hematologic findings of our patient at hospital admission, ICU admission, before and after plasma exchanges (PE), liver transplant (LT) and discharge from hospital.

| Admission | ICU | PEpre | PEpost | LT | Discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC×109 per L NR: 4–11×109 | 7.84 | 11.7 | 9.17 | 4.39 | 3.95 | 2.44 |

| Ht (%) NR: 36–51% | 37 | 27 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 30 |

| AST (U/L) NR: 5–40U/L | 263 | 246 | 169 | 68 | 84 | 46 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) NR: <1.2mg/dl | 8.1 | 21.2 | 25 | 26.5 | 30.8 | 0.8 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) NR: <0.6mg/dl | 3 | 8.5 | 10.9 | – | 11.5 | 0.2 |

| Alb (g/L) NR: 34–48g/l | 23 | 23 | 32 | – | 35 | 32 |

| INR | 2.2 | 3.26 | 3.95 | 1.69 | 2.14 | 0.94 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) Nr: 0.3–1.3mg/dl | 0.78 | 1.36 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 0.34 |

Patient progressed to ACLF grade 2, with MELD score 34 and Modified Nazar index 16. Fresh frozen plasma exchange (PE) was performed to control the hemolytic crisis, and she was admitted to the liver transplant (LT) waiting list; LT was performed 7 days later. Copper quantification in the explant was 1020μg/g (NR<250μg/g) and molecular diagnosis of the APT7B gene detected a known pathogenic variant (p.Met645Arg) and a probable pathogenic variant (IVS3-9T>A) in heterozygosis.

DiscussionThis case report highlights the difficulties in diagnosing WD, particularly in patients with other liver diseases. MALFD was highly probable because of steatosis in a patient with BMI 38 and arterial hypertension. However, steatosis is a frequent and unspecific finding, and its presence does not exclude other entities. Indeed, it is important to highlight that histological findings in WD can also include steatosis, with focal hepatocellular necrosis and no histochemically detectable copper.1 Adding to this, our case had neither neurological symptoms nor family history of WD. Thus, it may be possible that our patient had two different causes of liver disease, and probably WD was determinant for a rapid progression toward liver failure.

Considering the difficulties in the diagnosis, ceruloplasmin should be included as a screening tool in patients undergoing initial investigation of altered liver tests,3 even in patients with other causes of liver disease, particularly if certain features like steatosis are present. However, ceruloplasmin is a positive acute-phase reactant, so it may be increased in patients presenting with ALF (acute liver failure) or ACLF.1 Additionally, because of its hepatic synthesis, its blood levels can be decreased in advanced liver disease.1 For these reasons, it may be advisable to perform 24-h urine collection for copper regularly to better discriminate clinical suspicions of WD.1,4 In cases of acute onset of the disease, alkaline phosphatase to total bilirubin ratio<4 and AST:ALT ratio>2.2 could help to provide a better diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.5

An important clue, if present, to suspect WD is Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, commonly associated with severe liver disease,1,4 as shown in our case. PE can be required for a rapid removal of copper. Nonetheless, emergency LT should not be delayed, because untreated WD with ALF carries an almost 95% mortality.1,2

In conclusion, WD is a probably infradiagnosed disease whose diagnosis can be challenging.4 A high clinical suspicion is needed particularly if other causes of liver disease are present. Liver histology may confirm the diagnosis, but it can be tricky if copper is not specifically sought. Thus, performing serum ceruloplasmin and 24-h urine collection for copper regularly could be useful to screen patients with chronic liver diseases. In cases of hemolytic anemia and severe hepatic function derangement, the use of PE before LT may be necessary to stabilize the clinical picture. However, the only curative treatment currently is LT.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest regarding the present manuscript.