After almost 20 years using transient elastography (TE) for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis, its use has been extended to population screening, evaluation of steatosis and complications of cirrhosis. For this reason, the "Catalan Society of Digestology" commissioned a group of experts to update the first Document carried out in 2011.

Material and methodsThe working group (8 doctors and 4 nurses) prepared a panel of questions based on the online survey "Hepatic Elastography in Catalonia 2022" following the PICO structure and the Delphi method.

ResultsThe answers are presented with the level of evidence, the degree of recommendation and the final consensus after being evaluated by 2 external reviewers.

ConclusionTE uses the simplest and most reliable elastographic method to quantify liver fibrosis, assess steatosis, and determine the risk of complications in patients with cirrhosis.

Después de casi 20 años utilizando la elastografía de transición (ET) para el diagnóstico no invasivo de la fibrosis hepática, su uso se ha extendido al cribado poblacional, la evaluación de la esteatosis y las complicaciones de la cirrosis. Por ello, la “Societat Catalana de Digestologia” encargó a un grupo de expertos actualizar el primer Documento realizado en 2011.

Material y métodosEl grupo de trabajo (8 médicos y 4 enfermeras) elaboró un panel de preguntas en base a la encuesta online "Elastografía Hepática en Cataluña 2022" siguiendo la estructura PICO y el método Delphi.

ResultadosLas respuestas se presentan con el nivel de evidencia, el grado de recomendación y el consenso final tras ser evaluadas por 2 revisores externos.

ConclusiónLa ET utiliza el método elastográfico más sencillo y fiable para cuantificar la fibrosis hepática, evaluar la esteatosis y conocer el riesgo de complicaciones en pacientes con cirrosis. El documento ha sido avalado por la “Societat Catalana de Digestologia” y el “Col·legi Oficial d’Infermeres i Infermers de Barcelona”.

Transient elastography (TE) was first described in 2003.1 The technique and its diagnostic utility were summarised in the first Position Paper of the "Societat Catalana de Digestologia" (SCD) [Catalan Society of Gastroenterology].2 Since then, numerous studies and reviews have shown it to be both a simple and reliable non-invasive method for quantifying liver stiffness and the gold standard for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis.3 After almost 20 years, its use has become widespread as a screening and assessment tool for fatty liver disease and as a good technique for identifying complications of cirrhosis. In view of the considerable diversification in the way TE is used, the SCD thought it appropriate to provide a concise, practical update of the most important concepts in the use of TE in our day-to-day practice.

Material and methodsThe SCD commissioned a group of experts with professional practice in Catalonia, some of whom had participated in the previous position paper,2 to update and attempt to provide concise answers to the most common questions and challenging issues we encounter in routine clinical practice concerning the use of TE.

We collaborated with the SCD to find out how widely used the technique is here in Catalonia. After obtaining authorisation from the Board of Directors, we designed an online survey entitled "Elastografia Hepàtica a Catalunya 2022" [Hepatic Elastography in Catalonia 2022]4 in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The SCD technical secretariat sent the URL address to all the members of the society by post. The responses were registered anonymously. Only JAC has access to the individual response register.

On the basis of the survey, a panel of key questions was put together following the methodology adopted by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) according to the "PICO" structure (P: Patient, Population or Problem; I: Intervention, Prognostic Factor or Exposure; C: Comparison or Intervention; O: Outcome).5 The panel of questions was grouped under six different headings.

The document coordinators (JAC and XF) defined the criteria for selecting the panel of reviewers. The number of reviewers had to meet three criteria: 1/ two reviewers per section; 2/one third nurses; 3/two external reviewers. The composition of the panel was based on experience in elastography and chronic liver disease and geographical distribution. Participation in the first position paper was not a prerequisite,2 so the working group consisted of eight gastroenterologist-hepatologists and four nurses with expertise in performing and interpreting the technique. At least one pair of experts was assigned to each topic: a technical section (JAC, AA); a section on recommendations for the correct performing of TE (RF, TM, LM, MCB); three clinical sections orientated towards its use as a screening tool (IG, RMM), diagnostic tool (JMP, MV) and prognostic tool (MP, XF); and a section for the correct interpretation of the results (RF, TM, LM, MCB).

The review of the subject matter for each question had to be according to the Delphi method5 in order to achieve maximum academic consensus. Each response included the level of evidence (A, B or C), the grade of recommendation (strong or weak) and the consensus reached among the experts (from 0/8 to 8/8). Last of all, the entire contents were evaluated by two external reviewers, expert hepatologists (JG and PG), and the final recommendations and the degree of consensus (maximum 10/10) were adapted to their indications.

Part 1. Technical characteristics of transient elastographyWhat technique does TE use to quantify liver stiffness?Elastography is a radiological technique for measuring the propagation of waves in tissues produced by a mechanical or acoustic force. Transverse propagation waves or shear waves travel at a speed (m/s) that is faster the stiffer the tissue (kPa).6 The most natural way to produce this wave is by mechanical force and the easiest way to quantify its propagation speed through the liver is by TE.

TE was first described in 2003.1 The technical basis for TE was comprehensively covered in the first SCD position paper on TE.2 Since then, multiple studies and reviews have shown it to be a simple and reliable non-invasive method for quantifying liver stiffness and therefore the gold standard for non-invasive quantification of liver fibrosis.3

RESPONSE. TE uses the simplest and most reliable elastographic method to quantify liver stiffness and is therefore the reference method for non-invasively quantifying liver fibrosis. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

What are the other elastography methods?The propagation wave can be produced by an acoustic force at a single point ("point Shear Wave Elastography" or p-SWE) or over a wider area (2D-SWE).7 There are a multitude of ultrasound machines that incorporate the necessary software to measure the shear wave velocity (m/s) and proportionally the stiffness of the liver (kPa).

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was first described in 2006.8 MRE uses a transducer that generates low-frequency mechanical waves in the liver. The images are processed to obtain viscosity and elasticity maps. The elasticity is expressed in kPa and the values are significantly lower than with other elastography techniques.8 An advantage of MRE is that it assesses the entire liver parenchyma. However, it is an expensive scan requiring the participation of the radiology department and specific equipment and software, and it has limitations in patients with claustrophobia or iron overload of the liver. For these reasons, MRE has not been widely implemented in our setting.

SWE (p-SWE and 2D-SWE) has demonstrated greater applicability for assessing patients with ascites or obesity. However, it has the same limitations as TE, such as the need for fasting, the overestimation of values obtained in cases of elevated transaminases, cholestasis or congestive hepatopathy, and the difficulty in differentiating intermediate stages of fibrosis.9 Moreover, the quality criteria are still not well defined and its prognostic value in patients with liver cirrhosis has yet to be demonstrated.

RESPONSE. The other elastographic methods are more complex, share the same limitations as TE and have been less evaluated in our setting, so they cannot be considered as a reference. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 8/10.

What is the CAP and what is it for?The CAP is the controlled attenuation parameter of ultrasound designed to detect and quantify the degree of attenuation of ultrasound as it passes through a tissue. It was developed with the aim of quantifying the degree of fatty liver disease using an estimation of the ultrasonic attenuation. The CAP was first validated in 2010, taking the histological grade of steatosis as a reference, demonstrating a very good correlation (Spearman p = 0.81), with a diagnostic reliability measured by the ROC curve to identify steatosis of over 10% and of over 33% of 0.91 and 0.95, respectively.10

Since then, multiple studies and reviews have shown it to be a simple and reliable non-invasive method for estimating steatosis in patients with viral hepatitis, although obesity may be an important confounding factor in patients with fatty liver disease.11

RESPONSE. The CAP or controlled attenuation parameter of ultrasound enables non-invasive assessment of fatty liver disease. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 9/10.

What is the XL probe used for and when should we use it?As one of the most common factors in patients with steatosis is obesity, a new probe designed specifically for obese patients (with a body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) was validated in 2010. This XL probe produces a mechanical wave with a higher vibration amplitude and with a deeper focal distance (3.5 cm below the skin) that can obtain results in patients where the M probe (focal distance 2.5 cm) does not reach, and it therefore increases the applicability of TE.12 The XL probe also increases the diagnostic reliability of TE in obese patients, because its values correlate better with fibrosis stage than when assessed with the M probe.13 As the values obtained by the M probe in patients with obesity are erroneously higher and in some cases no results are obtained, the M probe should not be used in patients with BMI >35. In patients with a BMI of 30–35, the M probe can be used if the distance between the skin and Glisson's capsule measured by ultrasound is less than 2.5 cm. The type of probe to be used can also be selected according to the recommendations of the FibroScan® automated probe selection tool (auto-PS) software, which recognises the skin-to-capsule distance. To do this, start the auto-PS scan from the M probe and follow its recommendation, but switch to the XL probe if invalid or unreliable measurements are produced.14

RESPONSE. The XL probe allows reliable TE and CAP values to be obtained in patients with skin-to-capsule distance >2.5 cm in patients with obesity or when recommended by the automatic recognition system. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Can spleen stiffness be assessed with TE?An alternative to measuring liver stiffness by TE in patients with suspected portal hypertension is spleen elastography ("Spleen Stiffness", SS). SS has shown a good correlation with the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), which is the pressure gradient of choice for assessing portal pressure. SS values are three times higher than TE values in the liver and an SS <41.33 kPa rules out the presence of oesophageal varices.15 However, as there are patients who exceed the detection limit of 75 kPa, in 2018 an M probe was developed to measure SS emitting waves at 100 MHz, leading to a significant reduction in values.16 Although there are meta-analyses evaluating the diagnostic reliability of TE with the 50-MHz M probe for determining SS, studies using the 100-MHz M probe are still limited. The reference values could therefore change in the future.17

RESPONSE. Studies using the 100-MHz M probe to assess spleen stiffness are still limited, so its utility and reference values still need to be defined. Level of evidence C. Weak recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

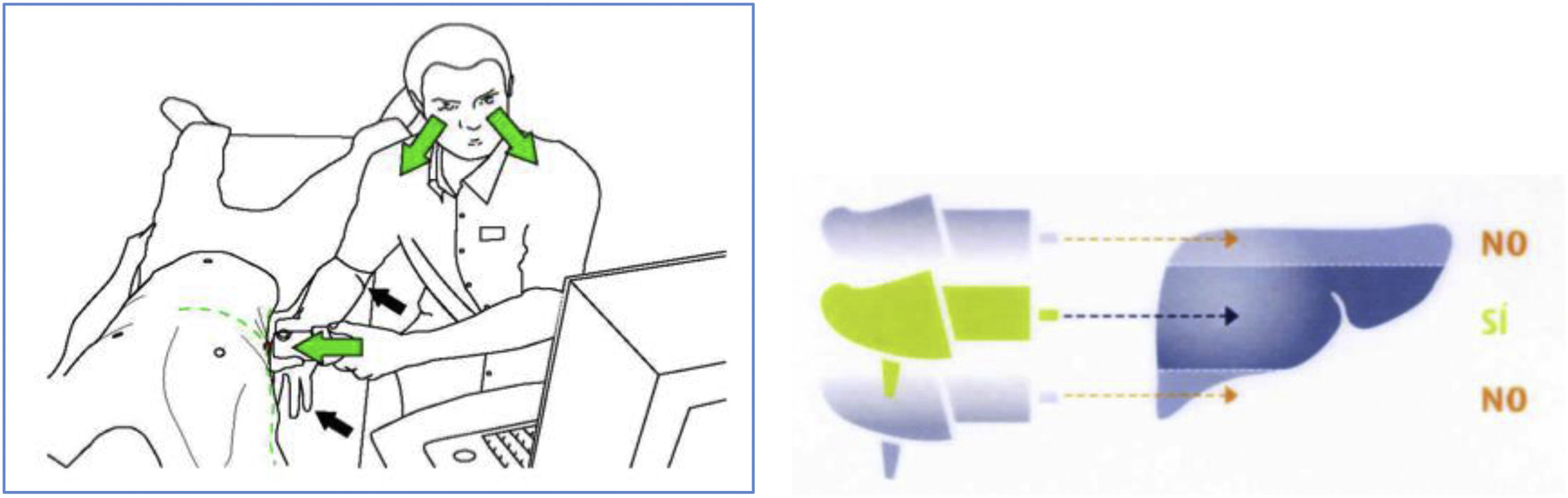

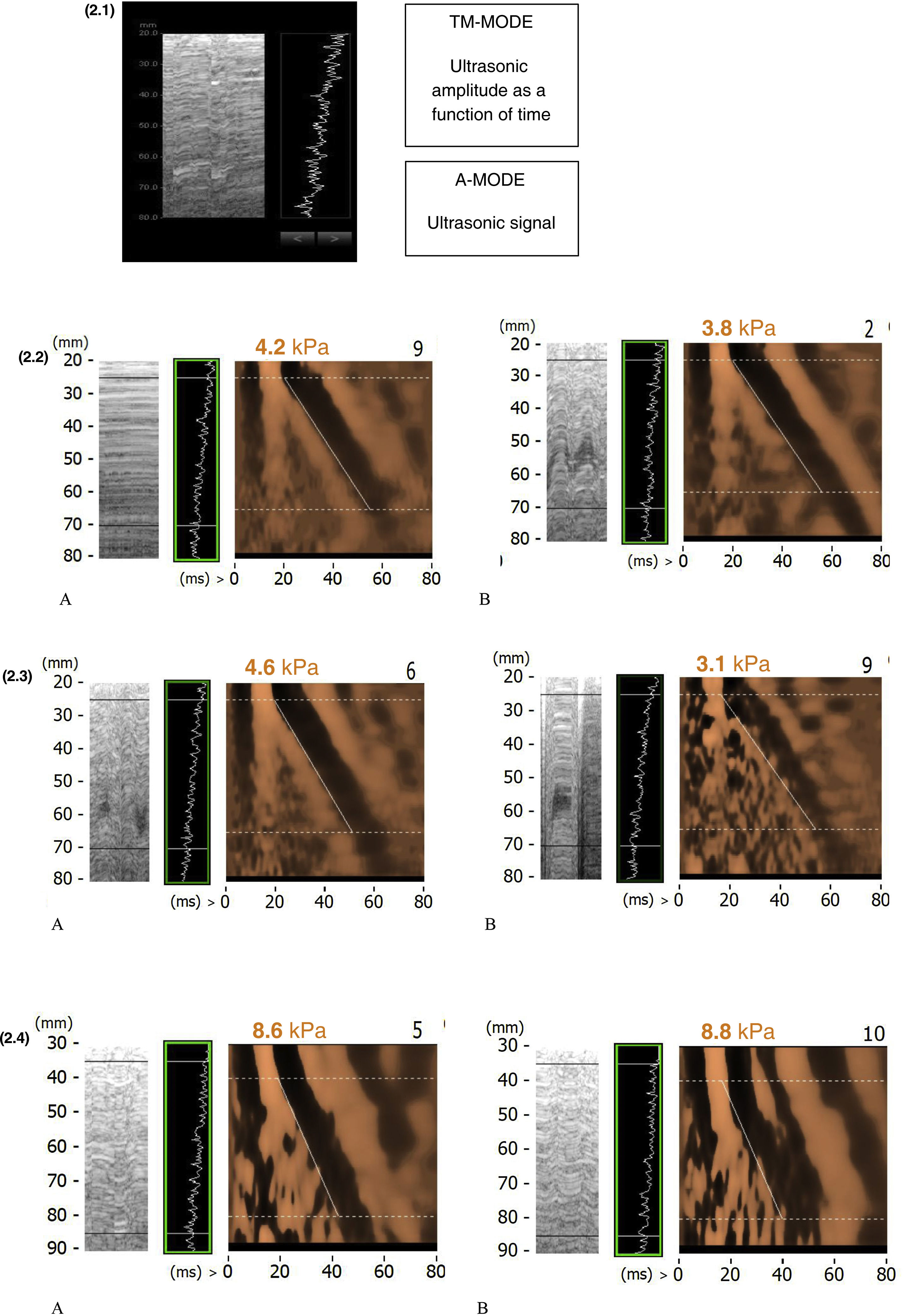

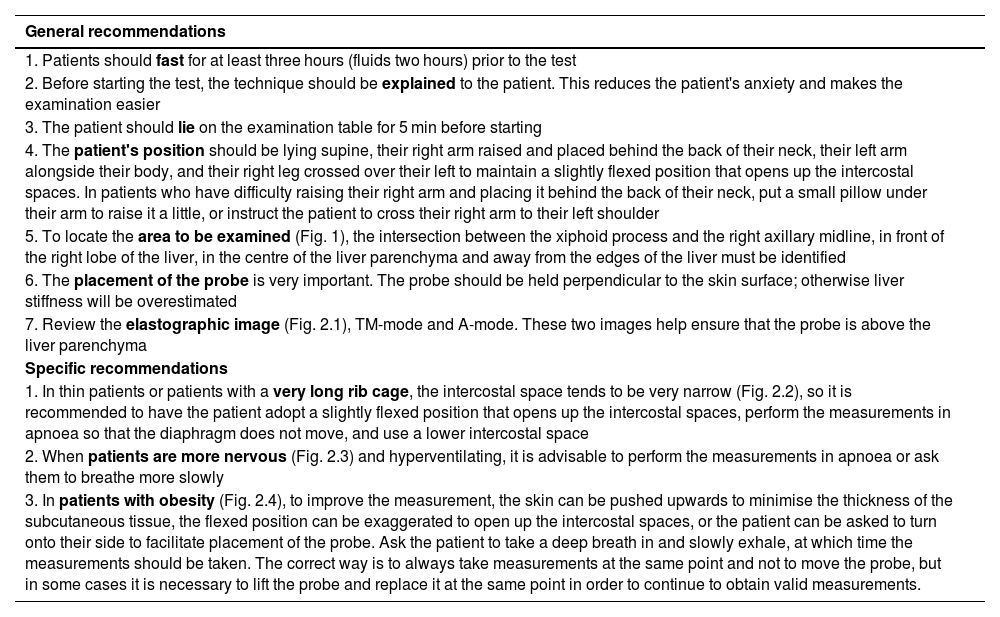

Part 2. Recommendations for quality elastographyHow to get reliable TE values?There are variables we can control before and during the test to achieve a quality examination (Table 1).18 The experience of the operator and the quality of the examination have been shown to influence liver stiffness results. Intake can increase TE values by up to 26% and exercise by up to 52%, so fasting for at least three hours and resting for at least five minutes before testing is recommended. Valsalva manoeuvres increase liver stiffness, while abstinence from alcohol is associated with a decrease in the results. The position of the patient, the measuring point and the type of probe must be chosen correctly (Fig. 1). The technique has to be thorough and it is important to use the right type of probe. The experience of the examiner is important regardless of the type of healthcare professional,19 but the learning curve is achieved earlier than with other ultrasound-guided methods.20 The examiner has to be able to recognise the typical elastographic pattern of the liver (Fig. 2.1) and reject images with artefacts (Figs. 2.2.B, 2.3.B and 2.4.B). During the test, individual measurements should be checked and the criterion of minimum dispersion respected; results with a dispersion of more than 30% should be discarded. In the event that the scan does not meet quality standards, this information should be recorded in the document and the possibility of repeating the scan should be considered if the factor influencing the result can be controlled.

Recommendations for good quality elastography.

| General recommendations |

|---|

| 1. Patients should fast for at least three hours (fluids two hours) prior to the test |

| 2. Before starting the test, the technique should be explained to the patient. This reduces the patient's anxiety and makes the examination easier |

| 3. The patient should lie on the examination table for 5 min before starting |

| 4. The patient's position should be lying supine, their right arm raised and placed behind the back of their neck, their left arm alongside their body, and their right leg crossed over their left to maintain a slightly flexed position that opens up the intercostal spaces. In patients who have difficulty raising their right arm and placing it behind the back of their neck, put a small pillow under their arm to raise it a little, or instruct the patient to cross their right arm to their left shoulder |

| 5. To locate the area to be examined (Fig. 1), the intersection between the xiphoid process and the right axillary midline, in front of the right lobe of the liver, in the centre of the liver parenchyma and away from the edges of the liver must be identified |

| 6. The placement of the probe is very important. The probe should be held perpendicular to the skin surface; otherwise liver stiffness will be overestimated |

| 7. Review the elastographic image (Fig. 2.1), TM-mode and A-mode. These two images help ensure that the probe is above the liver parenchyma |

| Specific recommendations |

| 1. In thin patients or patients with a very long rib cage, the intercostal space tends to be very narrow (Fig. 2.2), so it is recommended to have the patient adopt a slightly flexed position that opens up the intercostal spaces, perform the measurements in apnoea so that the diaphragm does not move, and use a lower intercostal space |

| 2. When patients are more nervous (Fig. 2.3) and hyperventilating, it is advisable to perform the measurements in apnoea or ask them to breathe more slowly |

| 3. In patients with obesity (Fig. 2.4), to improve the measurement, the skin can be pushed upwards to minimise the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue, the flexed position can be exaggerated to open up the intercostal spaces, or the patient can be asked to turn onto their side to facilitate placement of the probe. Ask the patient to take a deep breath in and slowly exhale, at which time the measurements should be taken. The correct way is to always take measurements at the same point and not to move the probe, but in some cases it is necessary to lift the probe and replace it at the same point in order to continue to obtain valid measurements. |

Examples of elastographic images. (2.1) Model elastographic image. (2.2) Elastographic image in thin patient. A. Correct image. In apnoea. B. Image with artefacts. Breathing without apnoea. (2.3) Elastographic image in a nervous patient. A. Correct image. Relaxed patient B. Image with artefacts. Nervous patient. (2.4) Elastographic image in obese patient. A. Correct image. Apnoea and stretching the adipose tissue. B. Image with artefacts. Breathing without apnoea.

RESPONSE. The nursing recommendations, examiner experience and correct probe selection ensure quality elastographic assessment. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Part 3. Utility of elastography as a screening toolIs TE useful for liver fibrosis screening in the general population?The prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the general population is considerably lower than the prevalence observed in secondary or tertiary care, where all non-invasive methods for fibrosis assessment, including TE, have been developed and validated. The accuracy of a test varies according to the prevalence of the disease. This is the spectrum effect, which means that in low prevalence populations the sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV) are lower. In a controlled study with biopsy, with a population in which 6% had advanced fibrosis, similar to the general population, TE demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 97%.21

In recent years, several studies, mainly in Europe and Asia, have evaluated the utility of TE in identifying patients with unknown liver disease and significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2).22–26 The largest study in the general population was conducted here in Spain, in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, where the presence of liver fibrosis was assessed in more than 3,000 individuals by means of TE. The prevalence of liver fibrosis ranged from 5.8% at a TE cut-off point of 8.0 kPa, to 3.6% with a cut-off point of 9.0 kPa.22 Interestingly, the highest rates of fibrosis were observed among subjects with risk factors for metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and subjects with high alcohol consumption. The results of the Caballería et al. study are similar to those of other studies in the general population, where the prevalence of significant fibrosis is 2.5%–7.5% depending on the TE cut-off point used (from 7.9 to 9.6 kPa). All these studies indicate that TE is a good method for detecting significant liver fibrosis in subjects without known liver disease and is useful for the detection of fibrosis in the community. In fact, the study in the northern metropolitan area of Barcelona shows that TE has a higher predictive accuracy compared to the NAFLD Fibrosis Score or FIB-4, confirmed in a recent study of more than 5,000 patients comparing serological non-invasive markers and TE.27 It should be noted that the availability of TE is limited in primary care settings, but it has been shown to be cost-effective in screening for liver fibrosis, further supporting its utility.28

RESPONSE. TE is a useful tool for liver fibrosis screening in the general population. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Is TE useful for liver fibrosis screening in patients with risk factors?With the high prevalence of risk factors for chronic liver disease, such as alcohol consumption, obesity and diabetes, and the fact that these factors are on the rise, we need to be able to define which population would benefit most from assessment and referral to specialised care. It should also be noted that to minimise the spectrum effect, it is essential that non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis are applied to populations with risk factors for liver disease rather than to non-selected populations.3 As mentioned above, in non-selected populations the sensitivity and PPV of TE are lower, but this can be optimised by better patient assessment and selection. The prevalence of advanced fibrosis depends on the risk factors of the cohorts included. In the study by Caballería et al., the prevalence of significant liver fibrosis (F ≥2) among subjects without risk factors (obesity, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome or risky alcohol consumption) was very low, at 0.4% compared to 5% in patients with one or more risk factor (p <0.001).22 Overall, although studies assessing TE in populations with risk factors mostly include small, heterogeneous cohorts, the prevalence of fibrosis detected by TE is in the region of 18–27% depending on the cut-off point used.29 Therefore, the scientific community recommends fibrosis screening in patients with metabolic risk factors or pathological alcohol consumption, or patients with human immunodeficiency virus.3

RESPONSE. TE is useful for liver fibrosis screening in subjects with risk factors for liver disease. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

What is the role of TE within the range of non-invasive methods available for liver fibrosis screening in the general population?TE has better diagnostic accuracy for detecting liver fibrosis in the context of screening than serological markers, particularly in the general population,22 but calculation of non-commercial biomarkers using analytical parameters is simpler and cheaper. It should be noted that serological biomarkers use two cut-off points. Values above the high cut-off point diagnose significant fibrosis and values below the low cut-off point rule out significant fibrosis. Overall, non-commercial serological biomarkers have a high negative predictive value (NPV >85%), enabling advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis to be ruled out with confidence, but have a low PPV for diagnosing fibrosis (PPV 40–70%).30 In addition, up to 30% of the values fall in the so-called grey zone, between the two cut-off points, meaning these patients cannot be classified with sufficient reliability.

Several studies have evaluated the sequential use of a serological biomarker followed by a second non-invasive method (direct biomarker or TE) and this strategy has proven to be effective in detecting more patients with liver fibrosis in the population and avoiding an excess of referrals.3,22 The population-based screening study conducted in the Barcelona metropolitan area showed that selecting patients with risk factors (obesity, diabetes, alcohol consumption) and applying the Fatty Liver Index (FLI) reduced the need for TE to only 35% of the initial population and was able to detect patients with liver fibrosis. In this study, only two patients out of the initial 3,000 remained undiagnosed.22 In another more recent example, sequential use of the FIB-4 followed by the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis score (ELF) was evaluated and shown to diagnose 30% of patients with significant fibrosis and 14% of patients with cirrhosis compared to only 8% and 6% when using the FIB-4 alone. Furthermore, using the two biomarkers sequentially reduced the need for referrals to specialised care by up to 70%.31 It is in this context that the scientific community recommends the staggered use of two non-invasive methods of fibrosis detection, recommending first a widely available method with a high NPV, such as indirect serological biomarkers, to reliably rule out that the patient has liver fibrosis, followed by a second more accurate method to diagnose fibrosis with certainty.28–30 These algorithms achieve a diagnostic accuracy of >90% for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis.32 This is where TE plays an important role and can be used in population screening as a second step in the algorithm. To further support its use in the algorithm, a cost-effectiveness analysis on the use of TE to screen for liver fibrosis has shown it to be cost-effective both in the general population and in sub-populations with risk factors.28

RESPONSE. TE is a good tool for stepwise screening for liver fibrosis after non-invasive serological methods. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

What is the best cut-off point for the detection of liver fibrosis in the general population by TE?The aim of population-based screening for liver fibrosis using TE is to identify patients with cirrhosis (F4), advanced fibrosis (F ≥3) or significant fibrosis (F ≥2), since it is the presence of fibrosis that determines the prognosis of patients with chronic liver disease and it is therefore these patients who need to be referred to specialised care.30,33 Patients with minimal or no fibrosis (F0-1) could be followed up in primary care. Various studies have evaluated the best cut-off points for detecting fibrosis or cirrhosis with TE, but these cut-off points differ according to the aetiology studied.32 In this context, being fully aware of the limitations of unifying a cut-off point for all aetiologies, the European guidelines (EASL) on the use of non-invasive methods for the detection of fibrosis recommend the cut-off point of 8 kPa as the best for deciding whether or not a patient has a high likelihood of liver fibrosis and, if so, recommend referral to specialised care for further study and follow-up.3 Note that this cut-off point is likely to change in the future. In the study by Caballería et al.,22 the best TE cut-off value for significant liver fibrosis (F ≥2) was 9.2 kPa, with a high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (78%). However, as this figure comes from a study where the number of biopsies was relatively low, it should be validated in future prospective studies in the general population before being implemented in clinical practice for screening purposes. There are currently four liver fibrosis screening studies in Europe and the USA, which will give us more information on the best cut-off points and the target populations for, and frequency of, screening.26

RESPONSE. The most reliable cut-off point for detecting significant fibrosis in the general population and recommending referral to specialised care is 8 kPa. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Is TE safe for pregnant women?TE can be used in pregnant women without risk to the foetus or the mother. In pregnant women, it should be noted that TE results may be falsely elevated in late pregnancy due to increased blood flow in the liver. Liver stiffness and CAP increase reversibly during pregnancy and decrease afterwards.34 Slightly elevated levels in the third trimester can therefore be considered a normal finding.

RESPONSE. TE can be used safely in pregnant women, although the results need to be interpreted taking into account pregnancy-associated changes. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Is TE useful for detecting liver fibrosis in the paediatric population?Since the introduction of the paediatric TE probe, an increasing number of studies evaluating the use of TE in the paediatric population have shown that TE is useful in detecting fibrosis in this population.35 However, several issues need to be taken into account when using and interpreting results in the paediatric population: 1/ the studies are in small cohorts; 2/ the cut-off points are different from the adult population; 3/ boys have higher TE values than girls; and 4/ the aetiology of liver disease in the paediatric population is different from the adult population, as the frequency of biliary atresia and cystic fibrosis are higher and influence TE results, so aetiology needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results. However, TE is a promising tool, and given the exponential increase in obesity and diabetes in the paediatric population, it is to be expected that TE could be a screening tool for MAFLD in this population, but population-based studies are lacking to assess its utility and cost-effectiveness in this setting.

RESPONSE. TE is a useful tool for liver fibrosis screening in the paediatric population. Level of evidence C. Weak recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Part 4. Utility of elastography for the assessment of liver fibrosis and fatty liver diseaseWhat is the best TE cut-off point for assessing liver fibrosis in advanced chronic liver disease?Different algorithms have been proposed for screening for significant liver fibrosis in primary care and other non-hospital settings to decide whether to perform TE and/or referral to specialised care. These vary according to geographical area, particularly in the use of serological biomarkers and non-invasive scales such as the FIB-4, the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) score or the "NAFLD Fibrosis score".33,36,37 In the hospital setting, TE can be used to assess whether the patient has advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), which is considered, according to the biopsy, as the presence of advanced fibrosis (F ≥3).38 The largest study published to date with liver biopsies recommends a TE value <7−8 kPa for ruling out advanced fibrosis.38

The term "compensated advanced chronic liver disease" (cACLD) reflects the continuum of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with ongoing chronic liver disease. This definition based on the measurement of liver stiffness aims to stratify the risk of clinically significant portal hypertension and decompensation, independent of liver biopsy. Although other cut-off points have been put forward,38 the most widely accepted are those proposed at the last Baveno VII conference.39 A TE cut-off point <10 kPa (regardless of the aetiology of chronic liver disease and in the absence of other known analytical or ultrasound signs of advanced chronic disease (for example, nodular surface, thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly) rules out the presence of cACLD, as these patients have a three-year risk of hepatic events of <1%.39 A value of 10−15 kPa is suggestive of cACLD and TE values >15 kPa are highly suggestive.39

Pons et al.40 analysed the optimal cut-off points for cACLD by TE according to aetiology, finding that 90% of patients with a TE >10 kPa had portal hypertension (HVPG >5 mmHg) whether it was chronic hepatitis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or due to hepatitis B virus (HBV), or alcoholic liver disease. However, in obese patients with MAFLD, the prevalence of portal hypertension was much lower. When measuring liver elasticity, a rule of 5 (10-15-20-25 kPa) can be used to indicate progressively higher relative risks of decompensation and death from liver disease regardless of aetiology.

RESPONSE. The most widely accepted TE cut-off point for ruling out cACLD regardless of aetiology is <10 kPa. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

In what situations is the current evidence with TE limited for assessing liver fibrosis?In patients with chronic HCV hepatitis who have achieved sustained viral response (SVR) and in patients with chronic HBV hepatitis who have been on antiviral treatment for years, TE has not proven to be a good tool for assessing the stage of fibrosis after treatment.41,42 A recent prospective, multicentre study conducted in our area with biopsies and TE after treatment showed a lack of correlation between TE values once SVR was achieved and the presence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.41 In patients with chronic HBV hepatitis, a recent prospective, multi-centre study with paired biopsies before treatment and 72 weeks after starting antiviral treatment showed that the decrease in TE is not reliable for estimating regression of liver fibrosis.42

The 8 kPa threshold has been shown to be useful in ruling out advanced fibrosis (F ≥3) in patients with chronic alcohol consumption,43 autoimmune hepatitis (AIH),44 primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC),45 or in liver transplant recipients, whether in the context of chronic rejection or other causes.46 In patients with PBC and PSC, a threshold of 9.5−10 kPa has been shown to be useful in identifying advanced fibrosis.47 However, confounding variables are common and the number of patients limited in these studies. In patients with active alcohol consumption, liver stiffness may be overestimated by inflammation and it may therefore be necessary to repeat TE when the inflammation is considered to have subsided (2–4 weeks of abstinence or reduction of consumption with biochemical improvement).48 In AIH, TE can be useful for monitoring disease activity along with transaminase levels and IgG levels, but it is advisable to repeat TE when the inflammation has been brought under control with immunosuppressive therapy in order to interpret the results.3

RESPONSE. TE is not a good tool for assessing fibrosis in patients with inactive viral liver disease (HCV with SVR or HBV with antiviral treatment). Alcohol consumption, inflammation and cholestasis are significant confounding factors in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune disease or cholangitis. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

How accurate is the CAP in MAFLD for diagnosing fatty liver disease?There is no information on CAP figures for diagnosing MAFLD in patients without metabolic syndrome. For the diagnosis of MAFLD, there are different studies and different cut-off points evaluated but we do not yet have consensus values for CAP. It seems that values >275 dB/m can be used to diagnose fatty liver disease, with a sensitivity of over 90%. However, ultrasound is still considered the first-line tool for the diagnosis of fatty liver disease despite its limitations (it only detects more than 12% hepatocyte involvement, has limitations in obese patients and has high inter-observer variability).3 The FLI, which includes abdominal circumference, BMI, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and triglycerides, has been shown to be an excellent screening tool for MAFLD in individuals with some metabolic risk factor.22 The SCD recommends that all patients with metabolic risk factors and an FLI >60 be assessed with TE.36

RESPONSE. CAP values >275 dB/m have demonstrated a sensitivity of >90% for detecting steatosis in patients with MAFLD. Ultrasonography is considered the radiological method of choice for the diagnosis of fatty liver disease despite its limitations. An FLI value >60 may be the best screening tool to identify MAFLD in patients with some risk factor. Level of evidence B. Weak recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

How accurate is the CAP in diagnosing fatty liver disease in disorders other than MAFLD?The CAP has also been shown to be associated with liver fat in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease.49 A CAP value >290 dB/m identified steatosis (hepatocyte involvement >5%) with a PPV of 92%, and a CAP value <280 dB/m ruled out severe steatosis (hepatocyte involvement >66%) with an NPV of 99%. Its diagnostic reliability was superior to BMI, abdominal circumference and ultrasound, but the differences with ultrasound were not statistically significant. It is worth noting that three out of four non-obese patients showed a rapid decrease (within 6 days) in the CAP after stopping alcohol, and it remained high in obese patients.49 Although in alcoholic liver disease (and also haemochromatosis and Wilson's disease) the histological substrate includes steatosis and steatohepatitis, there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of the CAP in these conditions. In transplant recipients, the CAP is starting to be evaluated as a tool to reliably detect steatosis after transplantation even in the absence of biochemical abnormalities,50,51 but there are insufficient data to make systematic recommendations on its use. The situation is similar for autoimmune liver diseases.52 There is also insufficient evidence to recommend the use of the CAP in scenarios where steatosis may play a more important role, such as in the assessment of the viability of donor livers for transplantation or the impact of steatosis on presinusoidal hypertension due to MAFLD in morbidly obese patients.

RESPONSE. In alcoholic liver disease, haemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, AIH, PBC and patients with morbid obesity or liver transplantation, the evidence for the use of the CAP to identify steatosis is still limited. Level of evidence B. Weak recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Part 5. Utility of elastography in identifying complications of cirrhosisCan clinically significant portal hypertension be identified with TE?The concept of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) is a haemodynamic concept and therefore requires the measurement of the HVPG and a value ≥10 mmHg. TE can be used to estimate the absence or presence of CSPH and therefore identify patients at increased risk of liver disease decompensation and related mortality.

TE values <10 kPa rule out CSPH and so identify patients at risk of liver disease-related decompensation and death <1% at three years. In contrast, a TE value >25 kPa is sufficient to identify the presence of CSPH (with specificity and PPV >90%), detecting patients at risk of showing endoscopic signs of portal hypertension and at greater risk of decompensation.39

By combining the TE value with the platelet count, we can increase the sensitivity and NPV of the diagnosis of CSPH. Thus, TE values <15 kPa with platelet count >150 × 109/l rule out CSPH (with a sensitivity and NPV >90%). In contrast, TE values from 15 to 20 kPa with platelets <110 × 109/l and TE values from 20 to 25 kPa with platelets <150 × 109/l have at least a 60% risk of developing CSPH.53

RESPONSE. TE has been shown to be useful in ruling out/identifying patients with CSPH. Combining TE with platelet count can increase the sensitivity and NPV for ruling out CSPH to above 90%. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Does each aetiology have differentiated TE cut-off points to identify the risk of decompensation?When assessing the cut-off point, it is very important to take into account the patient's BMI rather than the aetiology of the liver disease. An international cohort study was recently published identifying that a TE value of >25 kPa is the best cut-off point for identifying patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease, chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C and MAFLD without obesity who have CSPH (with a PPV >90%). In contrast, the same cut-off point in patients with MAFLD and obesity has a much lower PPV (62.8%). A model combining TE, platelet count and BMI ("ANTICIPATE-NASH model") has been described to improve the predictive ability of CSPH in this subgroup of patients. However, this model has yet to be validated.40

RESPONSE. A TE value >25 kPa has a PPV greater than 90% for identifying CSPH in patients with chronic liver disease due to alcohol, HBV, HCV and MAFLD without obesity, but not in obese patients with MAFLD. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 9/10.

Is TE useful in identifying patients with chronic liver disease but who do not have oesophageal varices?Patients with TE values <20 kPa who have a platelet count >150 × 109/l (Baveno VI criteria) have a very low likelihood (<5%) of having high-risk oesophageal varices on endoscopic study and therefore screening gastroscopy is not necessary.39,53

RESPONSE. TE, when combined with platelet counts (Baveno VI criteria), can identify patients without high-risk varices with a NPV of over 95%, so screening endoscopy would not be indicated. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

In screening for portal hypertension, once the aetiological cause has been eliminated, should the same cut-off points for TE be taken into account?The impact of eliminating the primary aetiological factor of cACLD is not well established. The paradigm of this situation is hepatitis C, as it has a very effective treatment. However, other factors such as obesity, diabetes and alcohol consumption may contribute to the progression of liver disease despite having eliminated the primary aetiological factor.

In this scenario, we do not yet have a reliable non-invasive tool to rule out CSPH. In the absence of cofactors, patients who achieve post-hepatitis C treatment SVR and who have a sustained decrease in TE value <12 kPa with platelets >150 × 109/l during follow-up have a very low likelihood of having CSPH and also therefore little risk of liver disease decompensation (sensitivity 99.2%).54 As a result, in this case screening for varices can be discontinued. However, screening for hepatocellular carcinoma should be continued, as there are no data to suggest that it has decreased to date.

Post-hepatitis C treatment and having achieved SVR, the same Baveno VI criteria can be applied to rule out the presence of high-risk oesophageal varices (those requiring treatment), TE <20 kPa and platelet count >150 × 109/l with a NPV of 100%. For the other liver diseases, we do not yet have robust data after eliminating the aetiological factor.39,55–57

RESPONSE. The impact of eliminating the aetiological factor of liver disease is not well established, but in patients with previous HCV infection who have achieved SVR, the Baveno VI criteria can be applied to rule out high-risk oesophageal varices. Level of evidence B. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

Is it useful to repeat TE during the follow-up of patients with cACLD?TE provides information on the prognosis of chronic liver disease at diagnosis and during follow-up. A significant decrease in TE during follow-up has been associated with a reduced risk of decompensation and reduced risk of liver disease-related mortality. A significant decrease in TE value is defined as a 20% decrease during follow-up with a TE value <20 kPa or a decrease to below 10 kPa. In patients not on beta-blocker therapy and not included in the CSPH screening programme with gastroscopy, annual TE and platelet count is recommended, and if the TE value increases to >20 kPa or the platelet count decreases to <150 × 109/l, screening gastroscopy would be recommended if the patient is not on beta-blockers.39

RESPONSE. TE gives information on the prognosis of chronic liver disease during follow-up and it is therefore recommended to perform TE and platelet count annually. If the TE value increases to >20 kPa or the platelet count decreases to <150 × 109/l, gastroscopy should be performed if the patient is not on beta-blockers. Level of evidence C. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

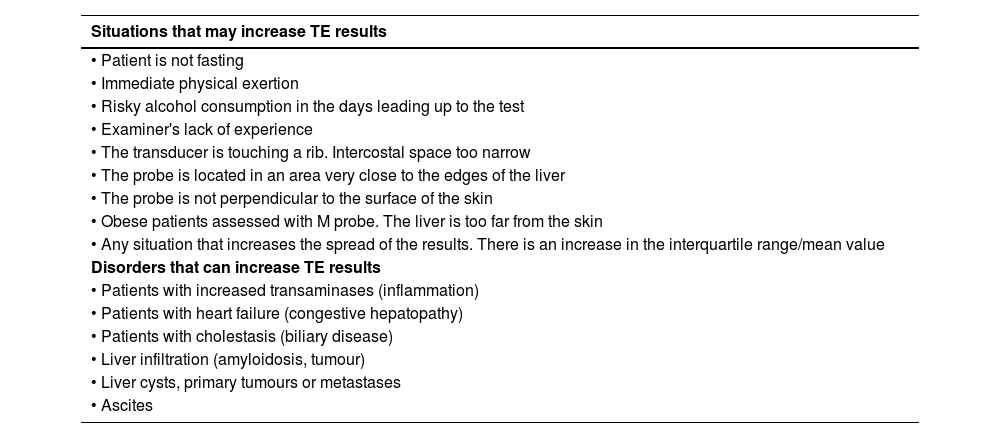

Part 6. Recommendations for interpreting the resultsWhat do we need to take into account when interpreting TE results to avoid committing errors?The elastogram does not provide an anatomical picture, it is a representation in graph form of the propagation of the percussion wave as a function of time and depth. The programme eliminates those elastograms that do not meet the quality criteria and, in this case, gives no numerical result (invalid measurement). However, there can be elastograms with anomalies that may be considered valid by the programme and the examiner has to be able to recognise these images and disregard them (Fig. 2.2.B, 2.3.B and 2.4.B). In addition, when interpreting TE results, we need to be familiar with situations that may increase liver consistency and thus raise values out of proportion to the fibrosis (Table 2).

Potential causes of liver stiffness value overestimation in TE.

| Situations that may increase TE results |

|---|

| • Patient is not fasting |

| • Immediate physical exertion |

| • Risky alcohol consumption in the days leading up to the test |

| • Examiner's lack of experience |

| • The transducer is touching a rib. Intercostal space too narrow |

| • The probe is located in an area very close to the edges of the liver |

| • The probe is not perpendicular to the surface of the skin |

| • Obese patients assessed with M probe. The liver is too far from the skin |

| • Any situation that increases the spread of the results. There is an increase in the interquartile range/mean value |

| Disorders that can increase TE results |

| • Patients with increased transaminases (inflammation) |

| • Patients with heart failure (congestive hepatopathy) |

| • Patients with cholestasis (biliary disease) |

| • Liver infiltration (amyloidosis, tumour) |

| • Liver cysts, primary tumours or metastases |

| • Ascites |

RESPONSE. As TE quantifies liver stiffness, examiners should be familiar with and take into account all situations that increase its consistency, as they may lead to an increase in results unrelated to liver fibrosis. Level of evidence A. Strong recommendation. Consensus 10/10.

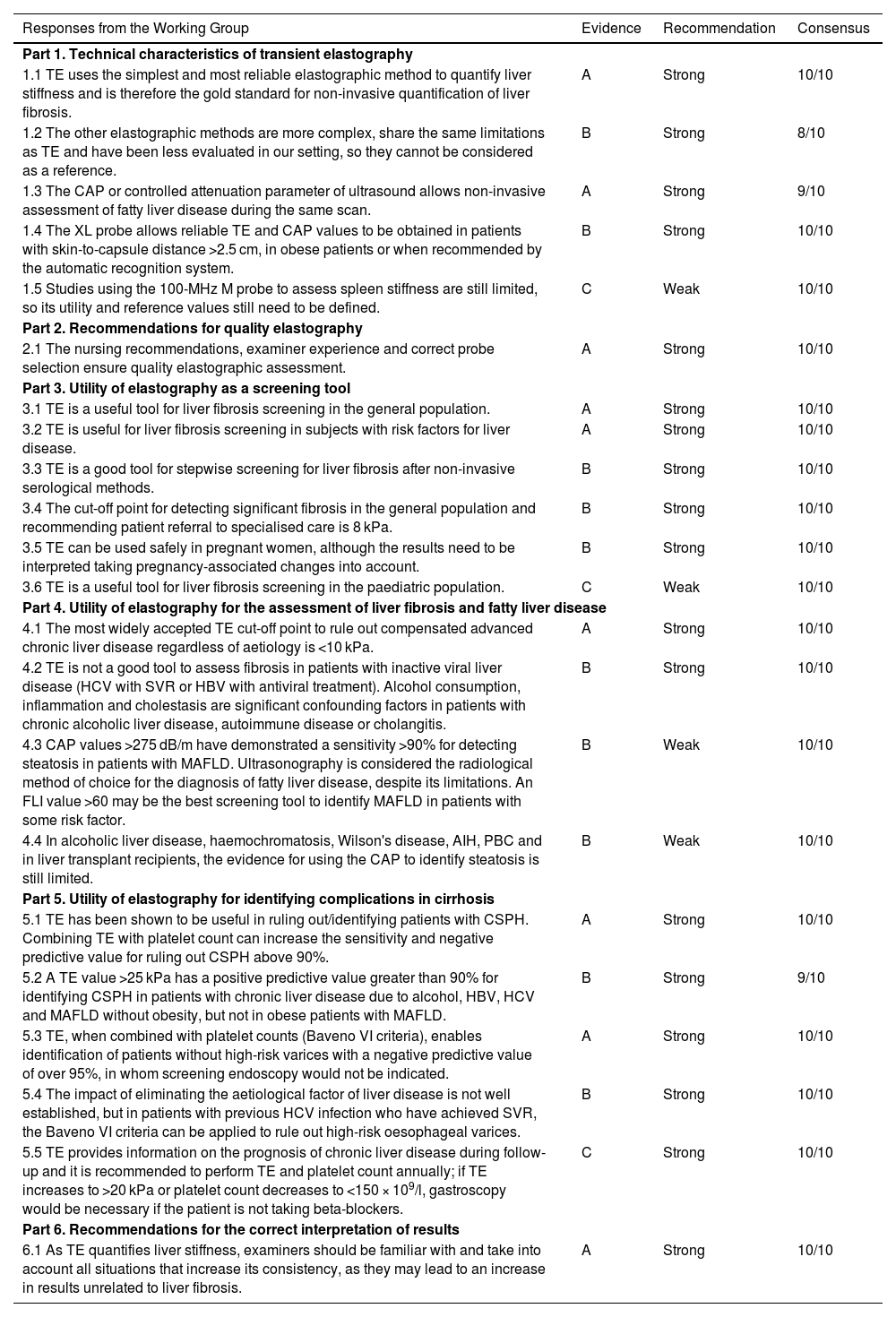

ConclusionsThe conclusions of this 2022 position paper on liver elastography include the responses of the expert group, the level of evidence, the grade of recommendation and the consensus reached for each question posed (Table 3).

Conclusions of the liver elastography position paper 2022.

| Responses from the Working Group | Evidence | Recommendation | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1. Technical characteristics of transient elastography | |||

| 1.1 TE uses the simplest and most reliable elastographic method to quantify liver stiffness and is therefore the gold standard for non-invasive quantification of liver fibrosis. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 1.2 The other elastographic methods are more complex, share the same limitations as TE and have been less evaluated in our setting, so they cannot be considered as a reference. | B | Strong | 8/10 |

| 1.3 The CAP or controlled attenuation parameter of ultrasound allows non-invasive assessment of fatty liver disease during the same scan. | A | Strong | 9/10 |

| 1.4 The XL probe allows reliable TE and CAP values to be obtained in patients with skin-to-capsule distance >2.5 cm, in obese patients or when recommended by the automatic recognition system. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 1.5 Studies using the 100-MHz M probe to assess spleen stiffness are still limited, so its utility and reference values still need to be defined. | C | Weak | 10/10 |

| Part 2. Recommendations for quality elastography | |||

| 2.1 The nursing recommendations, examiner experience and correct probe selection ensure quality elastographic assessment. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| Part 3. Utility of elastography as a screening tool | |||

| 3.1 TE is a useful tool for liver fibrosis screening in the general population. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 3.2 TE is useful for liver fibrosis screening in subjects with risk factors for liver disease. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 3.3 TE is a good tool for stepwise screening for liver fibrosis after non-invasive serological methods. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 3.4 The cut-off point for detecting significant fibrosis in the general population and recommending patient referral to specialised care is 8 kPa. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 3.5 TE can be used safely in pregnant women, although the results need to be interpreted taking pregnancy-associated changes into account. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 3.6 TE is a useful tool for liver fibrosis screening in the paediatric population. | C | Weak | 10/10 |

| Part 4. Utility of elastography for the assessment of liver fibrosis and fatty liver disease | |||

| 4.1 The most widely accepted TE cut-off point to rule out compensated advanced chronic liver disease regardless of aetiology is <10 kPa. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 4.2 TE is not a good tool to assess fibrosis in patients with inactive viral liver disease (HCV with SVR or HBV with antiviral treatment). Alcohol consumption, inflammation and cholestasis are significant confounding factors in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune disease or cholangitis. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 4.3 CAP values >275 dB/m have demonstrated a sensitivity >90% for detecting steatosis in patients with MAFLD. Ultrasonography is considered the radiological method of choice for the diagnosis of fatty liver disease, despite its limitations. An FLI value >60 may be the best screening tool to identify MAFLD in patients with some risk factor. | B | Weak | 10/10 |

| 4.4 In alcoholic liver disease, haemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, AIH, PBC and in liver transplant recipients, the evidence for using the CAP to identify steatosis is still limited. | B | Weak | 10/10 |

| Part 5. Utility of elastography for identifying complications in cirrhosis | |||

| 5.1 TE has been shown to be useful in ruling out/identifying patients with CSPH. Combining TE with platelet count can increase the sensitivity and negative predictive value for ruling out CSPH above 90%. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 5.2 A TE value >25 kPa has a positive predictive value greater than 90% for identifying CSPH in patients with chronic liver disease due to alcohol, HBV, HCV and MAFLD without obesity, but not in obese patients with MAFLD. | B | Strong | 9/10 |

| 5.3 TE, when combined with platelet counts (Baveno VI criteria), enables identification of patients without high-risk varices with a negative predictive value of over 95%, in whom screening endoscopy would not be indicated. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

| 5.4 The impact of eliminating the aetiological factor of liver disease is not well established, but in patients with previous HCV infection who have achieved SVR, the Baveno VI criteria can be applied to rule out high-risk oesophageal varices. | B | Strong | 10/10 |

| 5.5 TE provides information on the prognosis of chronic liver disease during follow-up and it is recommended to perform TE and platelet count annually; if TE increases to >20 kPa or platelet count decreases to <150 × 109/l, gastroscopy would be necessary if the patient is not taking beta-blockers. | C | Strong | 10/10 |

| Part 6. Recommendations for the correct interpretation of results | |||

| 6.1 As TE quantifies liver stiffness, examiners should be familiar with and take into account all situations that increase its consistency, as they may lead to an increase in results unrelated to liver fibrosis. | A | Strong | 10/10 |

Not funded.

Conflicts of interestXavier Forns has acted as a consultant for Gilead and Abbvie. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and guidance Dr Xavier Calvet provided during his presidency of the "Societat Catalana de Digestologia" [Catalan Society of Gastroenterology] for the creation of this paper.